Abstract

The article addresses key challenges and opportunities within the high jewelry industry. It explores how brands can target sustainability and diversification demands by consumers from the supply side. It details sustainability-oriented market trends and resulting challenges and opportunities for high jewelry brands, in particular regarding artificial lab-grown diamonds, without being solely focused on this option alone. The study implements a qualitative research methodology, using semi-structured interviews with eight professionals active in different parts of the high jewelry industry, thus covering a large share of all high jewelry companies. The interviews provide an in-depth understanding of the obstacles and opportunities faced by both traditional and new high jewelry brands. The findings of this study reveal the changing trends in the high jewelry industry. Sustainability has emerged as a key driver in consumer decision-making, with ethical concerns now taking a central role in brand strategy and supply chain practices. Diversification has emerged as a strategy to meet this demand without losing the brand’s luxury essence and to build brand power without compromising exclusivity and creativity. The study concludes by proposing an SOR-type framework for the interplay of sustainability and diversification deduced from the interviews.

Keywords:

luxury; jewelry; expert interviews; sustainability; diamonds; pearls; SOR model; grounded theory 1. Introduction

Due to its unique perceived value, long-term investment appeal, and above-average high-quality customer base, the demand for high-end jewelry remains strong (Mashhadi, 2024). High-end jewelry was booming in 2024, constantly setting records against the backdrop of the overall downturn in the luxury goods industry. Although the high jewelry market remains strong, it does not mean that diamond suppliers are in an equally favorable situation. De Beers’ diamond inventory has reached a new high since 2008. Due to multiple unfavorable factors, international diamond giant De Beers is facing its most severe inventory backlog since the 2008 financial crisis (Mining.com, 2024). Specifically, weak demand in major markets, intensified competition for laboratory-grown diamonds, and a decline in marriage rates due to the pandemic have caused the inventory value of the world’s largest diamond producer to decrease to approximately $2 billion (Moneycontrol, 2024). This development clearly indicates that the high jewelry industry is on a path of change because both the global economic situation and consumers’ attitudes have changed, and not just during the last decade (Serdari & Levy, 2018). The industry has integrated advancements in technology, besides becoming more sensitive regarding questions of sustainability (Mohr et al., 2022). The traditional notion of luxury, once harnessed to exclusive availability and a link with history, is changing to one of eco-awareness and diversity (Wang, 2023).

However, even identifying a generally accepted definition of high jewelry is ever more difficult (Cristini et al., 2022), beyond it being handmade, produced by a luxury brand, and made of precious metals. The preciousness of materials has shifted to the preciousness of values (Wirtz et al., 2020). Jewelry and other luxury products are increasingly defined by contemporary influences and contexts. Traditional high-end jewelry typically featured rare gemstones, such as diamonds and rubies, and precious metals, such as gold and platinum. Today, materials are no longer the only characterizing element to define if a jewelry item belongs to the sphere of luxury (Cappellieri et al., 2022). The classical criteria of luxury products and brands, however, hold for high jewelry brands as well. For this reason, the high jewelry sector in relation to the fashion industry’s haute couture is sometimes referred to as haute joaillerie (Felder, 2016). Following the definition of Barchfeld (2009) for haute couture, a working definition for the high jewelry market includes those luxury brands that offer ‘wildly expensive’ jewelry items that are ‘made-to-measure’ for the ‘ultra-rich’. Thus, luxury is determined by very high prices, even compared to normal jewelry standards, with very strict exclusivity usually produced by the designers themselves. Brands often, but not exclusively, look back on a heritage, which is an essential part of the brand identity. The term high jewelry or haute joaillerie, as compared to haute couture, however, is not controlled by a French institution and is limited primarily to brands with their seat in Paris.

Sustainability in the context of the high jewelry industry is intricately linked to mining for the raw materials. Mining gemstones and precious metals is destructive to the environment because the mining process leads to greenhouse gas emissions, animal habitat destruction, loss of biodiversity, water contamination, and erosion of the soil. The attainment of sustainable methods of mining is being pursued, but in many places remains a challenge (Biron Gems, 2023). Thus, their growing awareness of environmental and social issues has prompted consumers to begin showing interest in ethically sourced stones. Certification, like the Kimberley Process regarding diamonds, and efforts at the company level, such as the Responsible Jewelry Council, promote transparency and accountability along the supply chain (Kimberley Process, 2024), and research calls for the development of a more stringent supply chain (Antinarelli Freitas, 2024). Aside from this, several certification agencies exist globally that attest not only to the quality but also to the origin of the stones, e.g., the GIA, HRD, IGI, and EGL. All of these agencies have already started certifying lab-grown diamonds as well. Still, nowadays, the diamond supply chain is not devoid of ambiguities (de Angelis et al., 2021). From a technological point, using blockchain technology and advanced equipment in gemology can help in the detection of synthetic and treated stones (Cartier et al., 2018). It allows retailers and consumers to map a stone‘s history. In part, this technology, as well as related endeavors, is already used in tracing a gemstone‘s origins and thus detecting conflict stones (Smith et al., 2022). Comparable technologies, however, are not only applied to gemstones but also to precious minerals and metals as well (Calvao & Archer, 2021; Young, 2018).

From a cultural perspective, the jewelry industry is dominated by several major trends, such as cultural significance, expansion in the markets, economic well-being, young consumers’ preferences, and symbolism (Adnan, 2018) that must be embedded into the products (Mei & Ahmad, 2023). Increasingly more young consumers enter the market (Giovannini et al., 2015), and the jewelry industry must devise tactics that cater to their aesthetic demands and moral values (Guan, 2024). The younger generation pays more attention to personalization and multifunctionality (McKee et al., 2024), which has prompted brands to launch high jewelry products that combine innovation and practicality. Furthermore, the younger generation of customers also pays more attention to the embodiment of environmental protection (Pinho & Gomes, 2024) and cultural values (Easton & Steyn, 2022), which prompts brands to continue exploring how the concept of high jewelry can be diversified and meet ethical standards, e.g., through lab-grown gemstones or 3D printing techniques. While theoretical insights can be transferred from related sectors to the high jewelry sector, Khadeeja (2018) currently presents the only study focusing on the changing demand for jewelry in younger generations. Driven in part by their different values, several studies indicate that younger generations have a different willingness to pay (Kapferer & Michaut, 2019), which consequently will impact their purchase decision. Due to an increased price sensitivity, for younger generations, the market for counterfeit products poses as an increasingly more relevant alternative (Khan et al., 2022). However, as compared to the luxury fashion, accessory, or fragrance industry, high jewelry fortunately does not face a comparatively strong movement towards the purchase of counterfeit products yet (OECD & EUIPO, 2025).

Lab-grown gemstones offer an environmentally clean alternative to natural stones, and their consumer base includes environmentalists. On the other hand, traditional natural gemstones offer the rarity of high-quality natural stones that usually bear historical value (Khokhani & Mehra, 2025). The lab-grown diamond substitution policy could save 714 million cubic meters of landfill space, harvest 255 million kilograms of rice, feed 436 million people, and lift 1.19 million households out of hunger annually (Sun et al., 2024). A lab-grown diamond substitution policy could contribute to the sustainability efforts in a cost-saving manner, in particular since gemstones are regularly mined in countries with low levels of economic development. Thus, this policy would actively promote the first two of the UN’s sustainable development goals and, by reducing the effects of the resource curse in part, goal eight as well. Lawson and Chowdhury (2022) even argue that a more sustainable luxury industry could benefit the goal of reducing inequality. While not fully without criticism, sales of lab-grown artificial diamonds are continuously increasing. According to research by Tenoris, Madestones, and Bernstein, the proportion of all lab-grown diamond sales in the United States skyrocketed from 20% to over 50%, while natural diamond sales decreased from 80% to below 50% between 2021 and 2023 (Mades Stones, 2023).

Reacting to this trend and the near-perfect purity of lab-grown diamonds, luxury brands have begun to embrace natural diamonds with flaws and a wider range of colors in nature. At a high-end jewelry event in June last year, De Beers launched a unique necklace that blended rough diamonds with various cut forms and brown diamonds, gemstones that were previously often excluded from high-end jewelry. With the observed market growth of lab-grown gemstones, the jewelry industry needs to evaluate its business strategies critically for sustainability. Prada currently stands out as one of the few luxury brands operating at the high end that include laboratory-created diamonds within their products (Fedow, 2023). The brand has mainly reshaped people’s perception of artificial diamonds by emphasizing the benefits they bring and integrating them into the corporate social responsibility agenda. With experts’ predictions of the possibility of natural mineral depletion within the next 30 to 50 years, jewelry companies will eventually need to consider the adoption of artificial alternatives (Jowitt et al., 2020).

From a practical perspective, the Danish brand Pandora has already benefited from laboratory-grown diamonds. Looking back at the challenging fashion retail market in 2024, there were only a few winners, and Pandora was one of them. Since the beginning of 2024, the stock price of this company has risen by a cumulative 23%, with a market value of 91.3 billion Danish kroner, setting a new high in the 14 years since its listing. Since 2020, the company has increased brand appeal by reducing its store network, launching new series, and expanding its product categories (Pandora A/S, 2023). By 2024, Pandora confirmed that it had transformed from a single-product company to a diversified jewelry brand.

In the literature, sustainability in high jewelry, i.e., in particular, the gemstone industry, is rarely considered. Brandao et al. (2021), in their study, consider the gemstone industry, but in their discussion of measures to increase sustainability, they consider multiple stages of the production process of gemstones and assess their respective potential to increase sustainability. Similar to the diamond industry but considered in the scientific literature to a much lesser degree is the development of a more sustainable pearl industry, as discussed by Condello (2021). Another option to make the jewelry industry in general more sustainable is the use of alternative materials (Lerma et al., 2018; Ray, 2023; Tenuta et al., 2024) or the establishment of a circular economy for precious metals and materials (Ding, 2023; Keller Aviram, 2021). An example of this can be found with the brand Spinelli Kilcollin, which offered rings made of recycled materials.

In summary, Generation Z may be interested in lab-produced artificial diamonds and sustainably sourced pearls, but most people will still prioritize natural diamonds. The diamonds produced in the laboratory have the same atomic structure as natural diamonds and excellent quality, but customers are not only buying this structure (Novita Diamonds, 2024). As with other luxury goods, they buy the experience and the dreams. Conclusively, diversification could be a trend for jewelry brands, including the expansion into non-traditional luxury items (e.g., collaborations with other industries like fragrances or writing instruments). To attract a broader demographic, mid-tier luxury products can be designed and offered to them.

With very limited literature on the high jewelry market and sustainability developments therein, this study investigates how luxury jewelry changes based on ongoing dynamics in two areas: sustainability of the supply chain and market diversification. In a comparable context, the study by Schulte and Paris (2022) covers a comparable topical field, but they propose only a theoretical framework. Therefore, this study aims to approach the topic from an empirical point, and the main research questions for this study are as follows:

RQ1: How can high jewelry brands enhance supply chain sustainability while maintaining their luxury standards and ensuring favorable economic development?

RQ2: How does product diversification help high jewelry brands’ market positioning on their way to achieving supply chain sustainability?

To determine answers to these questions, interviews are conducted with experts from high jewelry brands. This study thereby contributes to the existing literature in three ways. It provides an in-depth study of a currently relevant trend that the high jewelry industry is facing and examines how they are coping with it. While studies exist that highlight the sustainability potential of lab-grown diamonds, these studies usually remain on a theoretical level and focus on the market for lab-grown diamonds alone (Khokhani & Mehra, 2025). This study integrates this market into the broader context of the high jewelry market. By focusing as well on the strategy of product diversification to integrate sustainability into the business model of high luxury brands, this study establishes that becoming more sustainable does not necessarily have to be an economically detrimental decision. On a business level, it thus mirrors the insights by Palma et al. (2014).

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology of choice in this study is a qualitative approach, i.e., in-depth interviews with experts in the jewelry industry conducted in early to mid-2025. The approach is ideal to investigate sustainability in the supply chain and diversification trends, and thereby understand the complex dynamics of the industry. The target population of experts consists of individuals involved in the fields of jewelry, gemstones, and sustainability. Purposive sampling was used to select participants who had significant experience and pertinence to the topics under study. The selection criteria include the following:

- The experts require detailed knowledge of high-end jewelry supply chains.

- They require expertise in sustainable practices in the jewelry sector.

- They should have brand development or marketing strategy experience.

- They should occupy leadership roles in either newly formed or established jewelry companies.

Regarding the interview guide, semi-structured interviews are used to enable in-depth discussions of interviewees’ areas of expertise while still assuring comparability across the corpus of all interviews. The development of the interview guide was carefully synchronized with the research questions and the theoretical underpinning of the research, ensuring an in-depth exploration of every thematic area. The questions were developed as open questions, allowing participants to provide detailed accounts of their experiences and views.

In total, the interview guide consisted of six parts. After informing participating experts about the topic of the interview and the collection and analysis of their statements in the context of a scientific study, their informed consent has been collected. Only after consenting did the interview itself start with an introductory section. The second and third sections concern themselves with sustainability and diversification endeavors in the high jewelry sector. In this regard, sustainability endeavors are not restricted solely to lab-grown diamonds but are phrased more broadly. Sections four and five consider the emergence of new brands in the industry and current investment trends. Even though these two parts were contained within the interview due to a broader research interest, to keep the topical consistency of the article and avoid deviations from the guiding research questions, they do not enter the analysis presented herein. The interview concludes in the sixth section with a summary of recommendations for companies active in the high jewelry industry.

In detail, the interview guide had the following structure:

- Introduction and Background

- Could you briefly describe your role in the jewelry industry?

- How long have you been working in the jewelry or related sectors?

- Sustainability in the High Jewelry Supply Chain

- What are the key challenges your company faces in implementing sustainable practices?

- How do you perceive the role of lab-grown diamonds in promoting sustainability?

- Are there other specific initiatives your company has undertaken to promote sustainability?

- Diversification of High Jewelry Concepts

- From your perspective, how does product diversification impact a brand’s market positioning?

- Could you share examples of diversification initiatives you’ve observed in the industry?

- Traditional vs. New Jewelry Brands

- What are the key strengths and weaknesses of traditional high jewelry brands?

- What do you think new brands should bring to the table in terms of market appeal?

- In your opinion, how important is it for brand managers to also have product design skills?

- Capital Investment and Market Trends

- What motivates capital investments in high jewelry brands?

- How do such investments influence brand creativity and strategic direction?

- What role does the Asia-Pacific market play in shaping the future of high jewelry, particularly regarding investments and consumer trends?

- Recommendations for the Industry

- How can high jewelry brands balance tradition and innovation to retain their heritage while staying relevant?

- What advice would you offer to brands aiming to appeal to younger, more sustainability-conscious consumers?

Part 1 of the interview allows for a respective assessment of the expert’s suitability for the study. Part 2 and question 6a address the first of the two research questions, while part 3 and question 6b address the second research question. Parts 4 and 5 have no relation to the current study. They have been listed in the overview above to give the reader the opportunity to assess potential biases resulting from them regarding the answers to part 6. Where parts 2 and 3 ask about industry developments, part 6 aims to elicit actionable recommendations. Above, the current problems that the industry is confronted with have been introduced. Question 2a aims to assess the experts’ perceptions thereof. While this study and a large part of the existing research focus on lab-grown diamonds, question 2b evaluates the underlying assumption of the primary relevance of lab-grown diamonds in sustainability endeavors. Question 2c adds to this assessment by focusing on alternative sustainability endeavors. Thus, part 2 generates insights into the current situation regarding sustainability activities in the high jewelry industry. Question 6a takes a step back and considers lab-grown diamonds and other endeavors in a more general context as innovations and tries to elicit their disruptive potential for the market as a whole. Acknowledging that a slight halo effect from the preceding discussion of sustainability endeavors persists, part 3 asks about diversification strategies in general. Thus, it allows us to assess if sustainability can be considered a tool for a diversification strategy in its own right (question 3b) and what effects this strategy might have on a luxury brand’s image. Part 2 thus challenges the underlying assumption that diversification, motivated in part by the changing preferences and values of younger generations, is a feasible solution for luxury jewelry brands. Question 6b brings this to the point by directly asking about the reaction towards an increasing number of younger consumers.

The interview study has been approved by the ethics committee of the International School of Management. All interviews were recorded after assuring informed consent from the interviewees. The original audio recordings were transcribed, and due to privacy assurances to the interview partners, they were consequently destroyed. The transcripts are available from the corresponding author. Note that the direct quotes reproduced in this article are taken verbatim from the answers of the interviewees. Since not all of them are native English native-speakers, several grammatical errors are present, leaving answers as given and unaltered. Analysis of the interviews is based on a grounded theory approach, and following the paraphrasing and categorization of the interview transcripts, we will use axial and selective coding to develop a theory. Herein, the grounded theory approach by Kuckartz and Rädiker (2023) is adopted, and hypotheses are developed based on the interviews that will constitute the theory answering the two underlying research questions.

3. Results

3.1. Expert Selection

Qualitative interviews do not strive to achieve representativeness, but in the context of this study, a total of eight expert interview partners could be recruited to take part in the study. Six of the eight interviewees directly work for high jewelry companies and have a history of working for others other than those stated below. The seventh expert (INT G) works for an investment company specializing in gemstones, precious metals, and jewelry, and the eighth (INT H) is a collector of antiquities and jewelry. Considering that Cognitive Market Research (2025) in the annual global report lists only 27 high jewelry companies, some of them, however, incorporating multiple brands, this study realizes a coverage rate of more than a fifth (22.22%) of all high jewelry companies. While for reasons of anonymity the names of the interviewees are not stated in this study, they represent the following brands, among others:

Rosenglanz (INT A);

NCE Pearly (INT B);

Millenia (INT C);

Tereza (INT D);

TASAKI (INT E);

Serendipity (INT F).

The experts originate from Germany, France, China, and Singapore. Thus, covering a comparatively large area and combining insights into multiple culturally different environments. Each of the conducted interviews lasted for about 30 min.

3.2. Evaluation of the Interviews

3.2.1. How Can High Jewelry Brands Enhance Supply Chain Sustainability While Maintaining Their Luxury Standards and Ensuring Favorable Economic Development?

The results of the eight expert interviews via axial coding have led to grouping findings into two broad themes following the underlying research questions, i.e., sustainability in high jewelry and product diversification & market expansion.

In the evolving world of high jewelry, sustainability has been an absolute necessity, which compels brands to develop strategies for reducing their footprint on the environment without sacrificing their heritage of luxury. Among the key measures in this aspect is the advent of lab-grown diamonds that offer buyers a more ethical as well as transparent choice compared to diamonds mined traditionally. The capacity of these to reduce the destruction of the environment and allow traceability is agreed upon by the majority of professionals. However, as much as they have gained in popularity, they have not yet entered the ultra-high-end range, where rarity and natural provenance are still key determinants of perceived value. A further issue concerns maintaining transparency throughout the supply chain, specifically in sourcing ethically responsible materials for high jewelry. End-to-end traceability is usually difficult for traditional brands to attain because of the complexity in their networks. On the other hand, newer firms are employing blockchain technology and circular economy principles to provide traceable data on sourcing so that customers can follow the journey of each part from origin to final product. This innovation promotes customer confidence and simultaneously pushes the industry towards better ethics.

The pearl jewelry sector has its sustainability issues, especially in reconciling luxury and the environment. Experts hold opinions that an opportunity should exist to inform consumers of sustainable farming practices that would conserve marine ecosystems while producing high-quality pearls. One of the key methods used to minimize the environmental impact of jewelry production while simultaneously guaranteeing quality and beauty is the use of recycled metals.

Despite these innovations, achieving a balance between sustainability and the ancient craft of producing high-quality jewelry is still one of the most critical challenges nowadays. As more companies are turning ‘green’, some in the industry evoke the difficulty of preserving exclusivity and the artisanal charm that have long been linked with the sector. Striking the balance entails seeking innovative solutions that honor the tradition of fine jewelry while embracing sustainable values that are favored by today’s consumers. In detail, the experts state the following:

‘Lab-grown diamonds appeal to eco-conscious and younger consumers since they reduce environmental footprints and ethical concerns. However, in the high jewelry industry, they cannot replace the appeal of natural diamonds.’(INT C, lines 370–374)

‘TASAKI has gained recognition for operating our wholly owned pearl farms, enabling us to maintain responsible aquaculture practices. In addition to that, we also take pride in investing in traceable diamonds and green packaging as a complement to researching new materials that support our sustainability objectives.’(INT E, lines 790–793)

Luxury jewelry brands are expanding beyond the scope of jewelry, tapping into interior design, bags, and other accessories. Not only does this strategic move boost brand exposure, but it also allows these houses to face an ever-changing consumer attitude from customers. Through expertise in lifestyle products, luxury jewelry houses can move beyond established connoisseurs and wealthy clients, tapping an expanded base while hopefully maintaining their base of elitism.

Apart from tapping into other forms of products, another developing tendency involves the blending of high jewelry with other markets, specifically by way of cross-industry collaborations and limited editions. The addition of precious stones to timepieces (watches) offers an attractive way in which brands can showcase expertise both in jewelry and watches. In addition, collaborations with other haute couture houses and luxury labels lead to extraordinary or one-of-a-kind pieces that combine jewelry brands with haute couture, attracting both connoisseurs and those devoted to fashion.

Forward-looking, established players as well as entrants are utilizing different kinds of strategies to establish and enhance their presence in the marketplace. Established high jewelry houses may continue focusing on heritage, master craftsmanship, and venerable pasts while maintaining prestige. On the other side, newer brands implement direct-to-consumer strategies, partnerships, and social-inspired strategies by way of creating niches in the crowded luxury market. By leveraging newer marketing strategies coupled with modern means of connecting with consumers, these newer players are redefining conventions in the luxury market, thus altering perceptions as well as the high jewelry experience. In detail, the experts say the following:

‘Product line expansion allows jewelry brands to expand their consumer base without altering their underlying character. As an example, companies that initially concentrated on classic diamond jewelry have added colored gemstones, collaborated on design, and produced retro-style pieces to cater to a new generation of shoppers.’(INT H, lines 39–42)

‘Some luxury brands integrate high jewelry into the timepiece, combining art and function. Others release limited-edition collaborations, fitting classic craftsmanship with modern trends. My boutique selects brands that offer everything from timeless to edgy design, providing variety within a luxury experience.’(INT C, lines 386–389)

The sustainability of supply chains has now become a key challenge for luxury jewelry brands in balancing environmental responsibility with exclusivity and craftsmanship in luxury. This section discusses the main challenges, industry strategic measures, and new approaches that companies are undertaking to enhance their sustainability while sustaining their prestigious status.

Based on the interview, three themes for key challenges were noticed: material traceability and ethical sourcing, not universally accepted lab-grown diamonds, and balancing craftsmanship, luxury, and sustainability. Below is their explanation in detail.

One of the most pressing challenges in high jewelry sustainability is to ensure the traceability of materials without compromising the rarity and exclusivity that define luxury. INT E highlighted the difficulty that comes with sourcing responsibly sourced materials. She emphasized the need to use traceability technology to ensure the origin of diamonds and pearls, which requires building a strong relationship with the supplier. ‘One of the most enduring challenges is procuring ethical materials without compromising on the level of rarity and exclusivity that is demanded in high jewelry. Being able to provide complete transparency throughout the supply chain, especially for pearls and diamonds, means working very closely with suppliers and investing in traceability technology.’ (INT E, lines 773–776).

INT H stated that antique jewelry and used jewelry help improve sustainability by reducing the need for extracting new minerals. However, the lack of transparency about the source of antique gemstones and metals is another major hindrance. ‘Among the challenges of high jewelry sustainability is traceability of materials, specifically for antique and second-hand jewelry. While antique jewelry is by definition sustainable as it promotes reuse and reduces the demand for new mining, it is challenging to trace the origin of gemstones and metals.’ (INT H, lines 17–20).

INT F acknowledged that artificially created diamonds provide an eco-friendly option with their conflict-free nature and environmental benefits. However, she argued that artificially created gems are missing the heritage factor and emotional appeal that come with natural diamonds, making them less desirable in the ultra-luxury jewelry market. From her perspective, lab-grown diamonds belong to another category. They can only be made into ‘accessories’, which means they can never serve as ‘high jewelry’. ‘For high jewelry, the key point would be beauty and rarity. To have these two elements is the key to be in the category of high jewelry. As lab-grown stones, they are beautiful but don’t have the rarity. They can be reproduced. For me, the lab-grown, currently they are affecting the market, but eventually they are from different markets. Lab-grown eventually will be accessories. And high jewelry will always stick to natural diamonds.’ (INT F, lines 124–128).

INT B viewed lab-created diamonds to be the ultimate sustainable option, thus eliminating the need for digging and reducing environmental damage. However, being the founder of a pearl brand herself, she emphasized the need to raise overall consumer awareness about sustainability in their mindsets. ‘Lab-grown diamonds are literally the epitome of sustainability because they bypass the entire process of mining that completely destroys the planet and damages local communities. NCE-Pearls is all about pearls, but it’s absolutely apparent that lab-grown diamonds are a hip, environmentally friendly option for other pieces of jewelry as well. Lab-grown diamonds allow companies to produce elaborate, high-end pieces without compromising their green and ethical stance.’ (INT B, lines 450–455).

INT C explained that several brands are incorporating lab-created or recycled diamonds as an option, but not replacing natural diamonds completely. In this way, they are meeting sustainability targets without losing the trust of traditional luxury consumers. This is a compromise. ‘Some of the brands in my store are adding lab-grown or recycled diamonds as a choice for sustainable alternatives without diluting luxury connotations. However, in high jewelry industry, they cannot replace the appeal of natural diamonds.’ (INT C, lines 371–374).

INT F expressed that some eco-friendly materials are not meeting the aesthetic and qualitative criteria that luxury jewelry connoisseurs look for. For this reason, she highlighted that the use of sustainability should not undermine brand exclusivity. For her brand, she admitted that it’s challenging to balance exclusivity with sustainability. ‘Traditional craftsmanship sometimes relies on the materials that have really scarce sustainable alternatives. High jewelry is especially this case. Balancing sustainability with exclusivity is challenging for us because we need eco-friendly materials at the same time meeting the expected quality for our collectors.’ (INT F, lines 116–119).

Furthermore, the NCE-Pearls’ founder stressed that many consumers are unaware of sustainable practices in the jewelry sector. As a result, educating them is vital to promoting the concept of sustainable luxury. ‘Also, it’s somewhat of a challenge to educate our customers on why sustainability is a concern in pearl jewelry, given that many of them do not really know or understand how pearl farming impacts society and the environment.’ (INT B, lines 443–446).

Based on the previous axial coding, the emerging themes can be turned into selective coding. The experts recommend strengthening supplier partnerships to uphold responsible aquaculture (extracted from INT E) (especially for pearl brands, like TASAKI and NCE-Pearls). High jewelry brands should aim to incorporate lab-grown diamonds, recycled gold, and responsible pearl farming while maintaining exclusivity (extracted from INT C and INT F). Finally, they should enhance the systems of the circular economy with pre-owned jewelry upcycling (extracted from INT H).

To make consumers more familiar with the issues of sustainability in high jewelry, the experts recommend using online platforms for educating consumers (extracted from INT B and INT F). Additionally, they should offer alternatives for sustainable luxury choices without compromising on aesthetics (extracted from INT C and INT E).

Initially, INT H stressed the growing use of blockchain authentication to track the origins of gemstones used in vintage and used jewelry to ensure authenticity and build trust. ‘One of the high-profile trends that is receiving more attention in the sector is using blockchain technology to verify the origin of high-value antique pieces.’ (INT H, lines 32–34).

On the other hand, INT E mentioned TASAKI’s investments in both traceable diamonds and responsible pearl farming. Both of these practices ensure ethical sourcing without diminishing luxury value. ‘TASAKI has gained recognition for operating our wholly owned pearl farms, enabling us to maintain responsible aquaculture practices. In addition to that, we also take pride in investing in traceable diamonds and green packaging as a complement to researching new materials that support our sustainability objectives.’ (INT E, lines 790–793).

INT F reported that they implemented a made-to-order production model in her company to minimize waste and reduce overproduction. Before they make pieces for clients, they choose the stones based on the criteria that, in the end, nothing will be wasted. On the other hand, her brand is also responsible for recycling services. If an old gold piece is no longer in good condition, it can be melted and remade into a new piece. During this process, she tries to guarantee ‘zero waste’. ‘We have workshops in China and France. As for jewelry, especially the rings, they have to be exactly the sizes of the future collectors. When we make the jewelry, it’s already the perfect size for the client. Another thing we do is that sometimes the clients already have a piece of jewelry that they inherited from their family, given by their grandmothers, for example. The style, the shape may no longer be in good condition. We will recycle the material and make a new piece of jewelry. But we don’t waste any gold in the process.’ (INT F, lines 131–136).

INT H advocated for a circular economy, where old jewelry would be reused, rebuilt, or resold. ‘There are various jewelry companies and collectors that support concepts related to a circular economy. Rather than dispose of old jewelry, they choose to reuse, rebuild, or sell it again. In addition, various companies use recycled gold and gems that are mined using environmentally friendly methods, thus improving their sustainability efforts.’ (INT H, lines 29–32).

NCE-Pearls’ founder, INT B, hosts a series of workshops and events. The activities raise consumer awareness about the environmentally friendly approach used during pearl cultivation and thus enable better consumer decision-making. ‘And we host workshops and events to educate people why sustainability in jewelry is such a big deal so that they can make more informed decisions when they purchase.’ (INT B, lines 460–462).

From the selective coding and expert insights, the following hypotheses can be deduced:

H1.

The improved traceability along the high jewelry supply chain increases consumers’ trust and reinforces the brand’s reputation.

This core assumption is supported by the traceable diamonds and responsible pearl cultivation instituted by TASAKI, as explained by INT E, combined with the use of blockchain authentication for pre-owned items, as mentioned by INT H.

H2.

High-end jewelry brands that use lab-created diamonds and recycled metals will most likely resonate with younger consumers who value sustainability, but they may face resistance from traditional luxury buyers.

The justification behind the second hypothesis is based upon INT F’s contention that cultured gemstones cannot replace natural gemstones in the luxury gemstone consumption space. The founder of NCE-Pearls, on the other hand, viewed such cultured gems as symbols of sustainability.

H3.

Education of consumers on sustainability, supplemented with online interaction, can lead to greater adoption of ethical jewelry.

The reasoning behind the third hypothesis is based on the comprehension of the value placed upon consumer education. For this, INT B and INT F utilize workshops and web-based assessments as core methodologies.

This part targeted the first of the two research questions, RQ 1, suggesting that attaining sustainability in the supply chains of high jewelry requires a subtle balance among ethical sourcing, material innovation, and luxury standards. While alternatives like synthetic diamonds, recycled metals, and blockchain technologies are viable options, the consumer mindset and industry tradition are sometimes not totally in line with them. To uphold the ideals of sustainability and exclusivity, it is necessary for brands to promote transparency, evolve production methods, and make consumers aware of the core principles behind ethical luxury.

3.2.2. How Does Product Diversification Help High Jewelry Brands’ Market Positioning on Their Way to Achieve Supply Chain Sustainability?

Product diversification has become an essential strategy among high-end jewelry houses to widen the consumer market, enhance visibility, and adapt to the changing demands in the market, i.e., in particular, the trend towards more sustainability. Whereas some houses diversify themselves by entering new product segments, such as watches, accessory lines, and home products, others focus on partnerships, novel materials, or custom products. This segment analyzes the impact of product diversification on brand positioning and consumer interactions based on the opinions and feedback from professionals.

INT E explained that a product diversification strategy allowed the brand to reach new consumers without compromising its luxury reputation. She cited the Balance collection by TASAKI as an example, which reinvents pearl jewelry using an architectural concept, thus appealing to a younger market segment without compromising the exclusivity of the brand. ‘At TASAKI, our iconic ‘Balance’ series reimagines pearl jewelry through modern, architectural eyes. The expansion of product categories, such as fine jewelry and bridal collections, further enhances the brand’s approachability while maintaining exclusivity.’ (INT E, lines 799–802).

INT F clarified how the expansion into the diverse operational structure allowed her brand to appeal to a wide range of consumers without sacrificing its core identity. She combined diverse traditional pearl jewelry with new, creative sculptural pieces, resulting in a harmonious and diverse visual style. She emphasized creativity and mentioned the popular ‘Bread Collection’, which was widely accepted by people in their twenties to fifties. In this way, her principle is ‘Jewelry should be something that brings you happiness’. ‘It’s very important to be creative. Like the new collection that we launched early this year, it’s a really fun collection that used the engraved gemstone centerpiece. We gave them a smiling face on top of the gemstone through technique and created the foot, the hand, and even the hair of a gemstone to make the gemstone look like something that belongs to your daily life. For example, we have the bread collection, like croissant, baguette, chocolate…Creativity is also the key to capture the younger generation. The bread collection is a huge success. People from age twenties to even fifties, their first impression when they look at the collection, it’s not about the price or values of the pieces. It just simply brings happiness to whoever is wearing them. That I think is key of jewelry. It’s supposed to bring you happiness and give you pleasure.’ (INT F, lines 234–247).

INT A mentioned that product diversification considerably made brands adapt to the changing preferences of consumers through the supply of items that ranged from minimal casual wear to bold fashion jewelry. ‘Product diversification allows a brand to build a more diverse consumer base and be better attuned to the changing tastes of its consumer. By offering a range of options—from informal daywear to dramatic, bold pieces to highly refined options—a brand is able to position itself as accommodating and diverse.’ (INT A, lines 577–580) INT A expressed that some brands allow customers to choose gemstones and engravings. In this way, personalized and one-of-a-kind items are created, which let customers build an emotional connection to the brand. ‘Some high-fashion companies, for instance, developed minimalist jewelry that one can use on a day-to-day basis. Some companies also personalize their offerings to enable their clients to engrave or use various stones in their merchandise.’ (INT A, lines 583–585).

The creator of NCE-Pearls argued that a wider range of products would enable luxury brands to be more accessible to various consumer groups, which include both price-sensitive buyers and seekers of luxury. ‘Product diversification is about allowing a brand to capture more customers and adapt to new marketplace demands. Offering various types of pearl jewelry across price points allows us to capture both budget-conscious individuals and those looking for something more elaborate.’ (INT B, lines 467–470).

How product diversification influences brand positioning and consumer engagement can be extracted from the previously developed themes, with INT E and INT H both advising to go diverse while maintaining the brand DNA (extracted from TASAKI’s ‘Balance’ series, Serendipity Jewelry’s mix of classic and avant-garde styles). Additionally, companies should expand product lines in ways that complement brand heritage and craftsmanship (extracted from INT A and INT F). Finally, they could use a made-to-order production model to deepen efficient management (extracted from INT B, INT F).

INT B found that consumers were increasingly valuing customized experiences, which showed their emotional attachment to the brand. ‘There are a lot of them getting into customizations also, allowing people to design their own pieces. Teaming up with fashion designers or influencers has also been a great way to expose their brand to new audiences.’ (INT B, lines 475–477).

By employing selective coding and expert judgments, the following hypotheses are developed.

H4.

Product diversification can enhance a high jewelry brand’s ability to attract new customer segments. It can be achieved without sacrificing its core identity.

Supporting this hypothesis are TASAKI’s ‘Balance’ collection (according to INT E), the combination of classic and new-era aesthetics offered by Serendipity Jewelry (according to INT F), and the diverse design alternatives offered by Rosenglanz.

H5.

Customization and interactive shopping experiences increase consumer engagement and brand loyalty in high jewelry.

The empirical evidence for the third hypothesis can be seen in personalized jewelry offerings (according to INT A, INT B, and INT F) and interactive customer experiences that lead to deeper emotional connections with the brand (according to INT B and INT F). It assumes that product diversification significantly contributes to defining consumer interaction and market positioning of luxury brands. With the launching of new product lines, collaborative ventures, or the design of specially crafted experiences, product diversification can increase the exposure of the brands in the marketplace while maintaining their aura of exclusivity. However, the diversification strategies by the brands must ensure alignment with the luxury positioning, avoiding overt commercialization.

4. Discussion

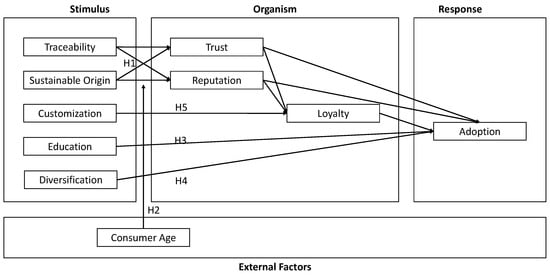

The five hypotheses postulated based on the results of the interview study can be summarized in a comprehensive model as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Resulting Model Structure.

On the left are those five constructs that the high jewelry company can directly influence. In the middle part are those constructs that do not explicitly exist but are latent constructs in consumers’ perceptions of the brand. Finally, on the right side of the figure are the measurable actions of consumers, i.e., purchasing sustainable high jewelry items. With these characteristics, the results of the study can be placed very well within the structure of a neobehavioristic stimulus–organism response (SOR) framework (Jacoby, 2008).

Even though the effect of trust and reputation on consumer loyalty and, in turn, the effect of consumer loyalty on the adoption, i.e., purchasing, of sustainable high jewelry items cannot be established from the answers of the experts, they are well-documented theoretically and empirically in the literature. Bulsara and Vaghela (2023), in their review, argue for the link between trust and brand loyalty as well as a direct link between trust the purchase intention. The link between reputation or brand image and consumer loyalty can be established via the review on this topic by Tahir et al. (2024). They also hint at the impact of brand image on purchase intention. Finally, Afandi and Marsasi (2023), among others, establish the link between consumer loyalty and purchase intention.

Traceability and sustainable origin are considered separate entities, as traceability of a diamond’s or pearl’s origin does not necessitate their sustainable origin; neither does a sustainable origin necessitate good traceability provided by companies, however often they are often discussed together. Hypothesis H2 can be interpreted as a moderating effect on the relations postulated via hypothesis H1.

Up to this point, the SOR framework has only been applied twice in the context of jewelry. Mohammad Shah and Linxue (2024) use a simplistic version of the SOR framework, with only four constructs deduced from theory, to model purchase intentions for Chinese jewelry items. Moraes et al. (2017) implement an unconventional form of the SOR framework, and in their consideration of ethical luxury consumption, they focus solely on the avoidance of conflict diamonds. Their model is externally motivated and utilizes data collected via consumer interviews. Thus, the model established above contrives the first consistent understanding of the dynamics in the high jewelry market, focusing on two aspects of sustainability. Unlike most implemented modeling frameworks, it has been developed based on the perception of experts with long-term and profound understanding of the market dynamics. The structure of a neobehavioristic SOR model has thus not been externally fixed but emerged from the grounded theory approach adopted herein. In this regard, this study deviates from most business studies, even qualitative ones. Other rare studies where an SOR framework emerges from a qualitative study include the studies by Dogru-Dastan and Yilmaz (2024) on theme parks or Min and Tan (2022) on livestreaming commerce. In both cases, the resulting models can be considered to be less sophisticated than the one developed herein. To the knowledge of the authors, very few qualitative expert-based studies on the high jewelry sector exist, and the present study is the only one where an SOR framework has been deduced from the experts’ assessments.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Insights and Theoretical Contributions

The findings of this study reveal the changing trends in the high jewelry industry. Sustainability has emerged as a key driver in consumer decision-making, with ethical concerns now taking a central role in brand strategy and supply chain practices. The study highlights the increasing focus on ethics within the high jewelry industry as consumers and brands are calling for responsible sourcing, environmentally friendly mining practices, and sustainable materials. Worthy of note is the increasing trend towards lab-grown diamonds. However, there exists resistance from the ultra-premium segment, where the diamonds are considered symbols of luxury, social status, and cultural heritage.

According to some experts, the emergence of digital technologies, blockchain technologies among them, has reshaped interactions between high jewelry houses and customers, making original experiential crafting and tailoring increasingly vital. High jewelry is a unique category that is described by its extraordinary, one-of-a-kind nature and higher artistry. Still, firms have worked hard towards the incorporation of complementary product lines that embrace luxurious qualities and also appeal to a wider consumer base. Diversification has emerged as a strategy to build brand power without compromising exclusivity and creativity. While diversification offers great opportunities, it simultaneously presents risks of commodification and brand dilution.

From a theoretical point of view, the study provides a first qualitative analysis that considers the aspects of sustainability and product diversification in the high jewelry industry. Implementing a sample of experts for the interview-based study that represents almost a quarter of the industry provides added value to the study results. By resorting to a grounded theory approach to analyze the study results, the expert answers could be placed within an SOR framework. Thus, this study is one of the few where the SOR framework results as a conclusion from an empirical study and is not externally enforced. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, in the field of jewelry and luxury research, it is the only such type of study. Thus, for future studies in the field of luxury jewelry, it presents researchers with a valuable, empirically founded tool to base their research on.

5.2. Recommendations for Practitioners

The results of this study have important implications for the high jewelry industry and stakeholders. The ability to keep pace with changing consumer demands, technological advancements, and sustainability concerns will be paramount to ensuring long-term prosperity in the industry. A key challenge facing the industry is a growing demand for products that are sustainable and ethical in terms of sourcing. Consumers, particularly younger consumers, have a higher awareness of the environmental and social impacts linked to what they purchase, which places pressure on brands to rethink or even redevelop their supply chains and manufacturing processes. This transformation has led to a focus by brands on factors such as transparency, traceability, and alternative materials like lab-created diamonds and recycled metal. While these sustainability efforts offer brands a way to enhance reputation and meet consumer expectations, they also pose challenges to maintaining exclusivity and perceived value, which are traditionally associated with high jewelry. In the future, there is a long way for the industry to work towards achieving a balance between luxury and sustainability to ensure that the aura around high jewelry does not erode.

The changing consumer demographics have a direct impact on the industry. Younger generations, particularly Millennials and Generation Z, are no longer those who only pursue social status. They redefine what luxury means to them in terms of experiences, personalized products, and sustainable consumption. This calls for a reevaluation of brand positioning and marketing strategies. While heritage retains high value, brands also have to emphasize their relevance and inclusivity in contemporary times.

Collaborative initiatives involving designers, artists, and non-traditional luxury categories like fashion, fragrance & scent, and cutting-edge technology can be seen to expand the appeal of high jewelry houses to new consumer segments without diluting their inherent essence. For these firms, it’s critical to understand that younger consumers highly value storytelling and authenticity, making a superficial marketing approach insufficient. Consumers today want a deeper connection with brands that they favor and patronize. Brands that connect with customers have a much better chance of retaining valuable customers long-term. Therefore, only if high jewelry houses have a clear vision with customers are they best prepared for long-term success.

Professionals and artisans in the high jewelry industry face various new opportunities and challenges with changing dynamics in the marketplace. High jewelry designers now have the responsibility to be equipped with technical skills and develop a more profound insight into consumer trends and sustainability concerns. Incorporating ethical materials, exploring new forms of artistic expression, and leveraging digital tools for enhanced customization are all qualities that designers should have when working for companies that stay ahead in the rapidly changing market.

In an ever-more globalized and digitalized world, consumers are surrounded by a rich kaleidoscope of cultural and artistic heritage. High jewelry houses face this challenge, combining carefully designed narratives with a strong sense of cultural awareness in collections that reflect integrity and respect. Through collaboration with local artisans, reinventions of traditional designs, and inspirations from local techniques in craftsmanship, they focus on cultural storytelling. However, it is important for these institutions to approach cross-cultural influences with thought and respect, thus ensuring that they pay homage and do not exploit cultural heritage. Through such efforts, high jewelry brands can be crowned as international leaders in artistic innovation while strengthening ties with consumers worldwide.

Finally, the best endeavors will not be successful if customers do not become aware of them. Considering that sustainability communication already is a delicate business for any brand, it becomes even more delicate for luxury jewelry brands. Thus, a fitting communication strategy targeting the different consumer groups needs to be developed (Machado & Goswami, 2024).

In conclusion, the high jewelry industry is now standing at the crossroads where tradition and innovation have to exist in harmony. While heritage and craftsmanship remain the pillars of luxury, they must be balanced with some adaptations to make brands remain relevant in a dynamic business landscape. Sustainability, technological innovation, and cultural responsiveness will determine the direction of high jewelry’s future, influencing not only corporate behaviors but also relationships with consumers. It is critical that industry stakeholders (like brands, investors, or designers) recognize that consumers nowadays are very different from the previous generations.

5.3. Limitations

The present research relied largely on semi-structured interviews carried out with industry professionals. Even if the interviews provided in-depth responses, the sample size remained limited, and opinions were largely derived from people who had immediate industry experience. Including a broader range of stakeholders, such as consumers, independent designers, and sustainability experts, in the study could enrich the findings. This can be achieved by implementing the developed model in an empirical quantitative study and testing it for customers of high jewelry brands.

The study centered on studying the high jewelry markets mainly in Europe and Asia, focusing strongly both on the established players who are long-time market players in the respective territories and the upstarts who are just starting to gain share in the competitive market. It is, however, worth noting that the market dynamics could vary considerably in other global market territories, including North America and the Middle East. The consumer preferences, the influence of cultures, and the different economic situations in the respective territories all play essential roles and could result in significant market and trend variations.

Considering the qualitative character of the research, the conclusions that arise from the research are essentially interpretive and based on a thematic examination. Although the specific research methodology is found to be effective in yielding in-depth findings, interviews cannot provide quantitative data to test the elicited trends.

The luxury jewelry market is marked by its strong dynamics, which are greatly influenced by the constant change in consumer behavior and preferences. Some trends, among them the push for sustainability and the continuous technological innovation, are liable to changes in the future, requiring consistent monitoring beyond the period covered by the current study. Future studies could enrich and advance qualitative findings by supplementing them with broad consumer surveys and detailed data-driven evaluations. This methodology could provide a precise measurement of realistic consumer behavior and purchasing decisions.

An extensive and detailed comparison and an in-depth analysis between high jewelry and other segments in the greater world of luxury items, i.e., haute couture, luxury watches, and premium fragrances, show promising potential. The insights could be used to reveal the shared impacts and collective influences found in the industry.

Certifications in the jewelry industry are valued as authentic and perceived as standards when purchasing and investing. An important characteristic of these certifications is that their rating standards change gradually because of the environmental standards or diamond scarcity itself. This already calls for regularly updated studies. Evaluation of the efficiency of certification models, e.g., Fairmined gold and the Responsible Jewellery Council’s established criteria, could significantly advance the establishment of a reliable and credible image according to consumers, who are becoming increasingly discerning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.P., C.B. and S.D.; methodology, J.K.P. and S.D.; validation, J.K.P.; formal analysis, S.D.; investigation, S.D.; data curation, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.P. and C.B.; writing—review and editing, J.K.P. and C.B.; visualization, J.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the International School of Management (protocol code 17-JP-K-2025 and 29 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to data confidentiality interview transcripts will be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adnan, A. (2018). The history, art & culture of Jewelry. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/56865921/The_History__Art___Culture_of_Jewelry_-_Daily_Times-libre.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Afandi, M., & Marsasi, E. G. (2023). Fast food industry investigation: The role of brand attitude and brand loyalty on purchase intentions in generation Z based on theory of reasoned action. BASKARA: Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinarelli Freitas, F. (2024). High jewelry meets sustainability: Designing guidelines to promote traceability in the high jewelry supply chain [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Politecnico di Milano. Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/233633 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Barchfeld, J. (2009). Haute couture goes cold as recession lingers. Available online: https://eu.theledger.com/story/news/2009/07/12/haute-couture-goes-cold-as/8064189007 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Biron Gems. (2023). Biggest environmental impacts of gemstone mining. Available online: https://biron-gems.com/biggest-environmental-impacts-of-gemstone-mining/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Brandao, L., de Alencar Naas, I., & de Oliveira Costa Neto, P. L. (2021). Sustainable development of gem production: An application of the analytical hierarchy process. International Journal of the Analytic Hierarchy Process, 13(3), 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulsara, H. P., & Vaghela, P. S. (2023). Trust and online purchase intention: A systematic literature review through meta-analysis. International Journal of Electronic Business, 18(2), 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvao, F., & Archer, M. (2021). Digital extraction: Blockchain traceability in mineral supply chains. Political Geography, 87, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellieri, A., Da Moreira Silva, F., Rossato, B., Tenuta, L., & Testa, S. (2022). Hand-made jewelry in the age of digital technology. Human Dynamics and Design for the Development of Contemporary Societies, 25, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, L. E., Ali, S. H., & Krzemnicki, M. S. (2018). Blockchain, chain of custody and trace elements: An overview of tracking and traceability opportunities in the gem industry. Journal of Gemmology, 36(3), 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognitive Market Research. (2025). High jewellery market report 2025. Available online: https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com/high-jewellery-market-report (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Condello, A. (2021). Viable pearls and seashells: Marine culture and sustainable luxury in Broome, Western Australia. In I. Coste-Manière, & M. Gardetti (Eds.), Sustainable luxury and jewelry (pp. 55–74). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristini, H., Kauppinen-Räisanen, H., & Woodside, A. G. (2022). Broadening the concept of luxruy: Transformations and contributions to well-being. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(4), 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Angelis, M., Amatulli, C., & Petralito, S. (2021). Luxury and sustainability: An experimental investigation concerning the diamond industry. In I. Coste-Manière, & M. Gardetti (Eds.), Sustainable luxury and jewelry (pp. 179–198). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K. (2023). Creating new jewellery with precious metals recovered from electronic waste. The Design Journal, 26(2), 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru-Dastan, H., & Yilmaz, B. S. (2024). The stimulus-organism-response approach to the overcrowding problem: Qualitative evidence from theme park visitors. Journal of Leisure Research, 55(3), 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, C., & Steyn, R. (2022). Millennials hold different cultural values to those of other generations: An empirical analysis. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(1), 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedow, L. (2023). Prada debuts lab-grown diamond jewelry collection. Available online: https://nationaljeweler.com/articles/12378-prada-debuts-lab-grown-diamond-jewelry-collection (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Felder, R. (2016, May 12). Haute is hot. The New York Times. Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA452138267&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=03624331&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon~f94d532f&aty=open-web-entry (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Giovannini, S., Xu, Y., & Thomas, J. (2015). Luxury, fashion consumption and generation Y consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(1), 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X. (2024). Research on the co-creation of young people in jewelry design connotation. Innovation Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 13, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J. (2008). Stimulus-Organism-Response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowitt, S. M., Mudd, G. M., & Thompson, J. F. (2020). Future availability on non-renewable metal resources and the influence of environmental, social, and governance conflicts on metal production. Communications Earth & Environment, 1(1), 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.-N., & Michaut, A. (2019). Are Millennials really redefining luxury? A cross-generational analysis of perceptions of luxury from six countries. Journal of Brand Strategy, 8(3), 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller Aviram, D. (2021). Traceability, sustainability, and circularity as mechanism in the luxury jewelry industry creating emotional added value. In I. Coste-Manière, & M. Gardetti (Eds.), Sustainable luxury and jewelry (pp. 87–115). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Khadeeja, A. (2018). The art of Saudi traditional jewellery: Rejuvenation for a contemporary world [Ph.D. dissertation, The Australian National University]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/108eafa0dc742c5852a1c659042db750/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Khan, S., Fazili, A. I., & Bashir, I. (2022). Constructing generational identity through counterfeit luxury consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(3), 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhani, O. J., & Mehra, P. (2025). Factors affecting the demand of lab-grown diamonds: A case of India. In A. Sedky (Ed.), Building business knowledge for complex modern business environments (pp. 443–466). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberley Process. (2024). What is the KP? Available online: https://www.kimberleyprocess.com/about/what-is-kp (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2023). Qualitative content analysis: Methods, practice and software. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, L., & Chowdhury, A. R. (2022). Women in Thailand’s gem and jewellery industry and the sustainable development goals (SDGs): Empowerment or continued inequity? Environmental Science & Policy, 136, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma, B., Dal Palù, D., Actis Grande, M., & de Giorgi, C. (2018). Could black be the new gold? Design-driven challenges in new sustainable luxury materials for jewelry. Sustainability, 10(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L., & Goswami, S. (2024). Marketing sustainability within the jewelry industry. Journal of Marketing Communications, 30(5), 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mades Stones. (2023). Lab-grown diamonds: Half of loose diamond sales in the USA. Available online: https://www.madestones.com/2023/11/09/labgrown-diamonds-half-loose-diamonds-sales-usa/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Mashhadi, S. (2024). The psychology of customer engagement in jewelry sales: An investigation into persuasion techniques [Unpublished Bachelor’s thesis]. Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/870293 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- McKee, K. M., Dahl, A. J., & Peltier, J. W. (2024). Gen Z’s personalization paradoxes: A privacy calculus examination of digital personalization and brand behaviors. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(2), 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L., & Ahmad, N. B. (2023). A review of current cultural jewellery trend. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11(5), e839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y., & Tan, C. C. (2022). A qualitative interviewing finding of customer perceptions in livestreaming commerce. RMUTR & RICE International Conference, 2022, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mining.com. (2024). De Beers sitting on largest diamond inventory since 2008. Available online: https://www.mining.com/de-beers-sitting-on-largest-diamond-inventory-since-2008-ft-reports/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Mohammad Shah, K., & Linxue, Z. (2024). Development of a research model of Chinese jewellery e-commerce using the SOR-model—The role of branding. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 16(4), 1791–1815. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, I., Fuxman, L., & Mahmoud, A. B. (2022). A triple-trickle theory for sustainable fashion adoption: The rise of a luxury trend. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 26(4), 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneycontrol. (2024). De Beers’ diamond inventory grows to $2 billion amid weak Chinese demand, lab-grown competition—Report. Available online: https://www.moneycontrol.com/europe/?url=https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/markets/de-beers-diamond-inventory-grows-to-2-billion-amid-weak-chinese-demand-lab-grown-competition-report-12897804.html (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Moraes, C., Carrigan, M., Bosangit, C., Ferreira, C., & McGrath, M. (2017). Understanding ethical luxury consumption through practice theories: A study of fine jewellery purchases. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novita Diamonds. (2024). Lab-grown vs. real mined diamonds. Available online: https://novitadiamonds.de/en/lab-grown-vs-real-mined-diamonds (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- OECD & EUIPO. (2025). Mapping global trade in fakes 2025: Global trends and enforcement challenges. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/05/mapping-global-trade-in-fakes-2025_5c812e3c/94d3b29f-en.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Palma, E. P., Maffini Gomes, C., Marques Kneipp, J., & Barbieri da Rosa, L. A. (2014). Sustainable strategies and export performance: An analysis of companies in the gems and jewelry industry. Review of Business Management, 16(50), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandora A/S. (2023). Annual report 2023. Available online: https://www.pandoragroup.com/investor/news-and-reports/annual-reports (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Pinho, M., & Gomes, S. (2024). Environmental sustainability from a generational lens—A study comparing generation X, Y, and Z ecological commitment. BSR Business and Society Review, 129(3), 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S. (2023). Perception of non-conventional materials as jewellery and awareness of sustainability among Indian consumers. In A. Chakrabarti, & V. Singh (Eds.), Design in the era of industry 4.0 (Vol. 2, pp. 989–1001). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M., & Paris, C. M. (2022). Supply chain transparency, ethical sourcing, and synthetic diamond alternatives: Exploring the perspectives of diamond retailers. International Journal of Intelligent Enterprise, 9(4), 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdari, T., & Levy, J. (2018). A framework that describes the challenges of the high jewelry market in the US. Luxury-History, Culture, Consumption, 5(3), 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. M., Smit, K. V., & Shirey, S. B. (2022). Methods and challenges of establishing the geographic origin of diamonds. Gems & Gemology, 58(3), 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Jiang, S., & Wang, S. (2024). The environmental impacts and sustainable pathways of the global diamond industry. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A. H., Adnan, A., & Saeed, Z. (2024). The impact of brand image on customer satisfaction and brand loyalty: A systematic literature review. Heliyon, 10(16), e36254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenuta, L., Testa, S., Antinarelli Freitas, F., & Cappellieri, A. (2024). Sustainable materials for jewelry: Scenarios from a design perspective. Sustainability, 16(3), 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2023). Design for circular cosmetics: A smart and green device for circular cosmetics [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. Politecnico di Milano. Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/214598 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Wirtz, J., Holmqvist, J., & Fritze, M. P. (2020). Luxury services. Journal of Service Management, 31(4), 665–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S. B. (2018). Responsible sourcing of metals: Certification approaches for conflict minerals and conflict-free metals. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23, 1429–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).