When Money Gets Tight: How Turkish Gen Z Changes Their Fashion Shopping Habits and Adapts to Involuntary Anti-Consumerism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Country Backbround

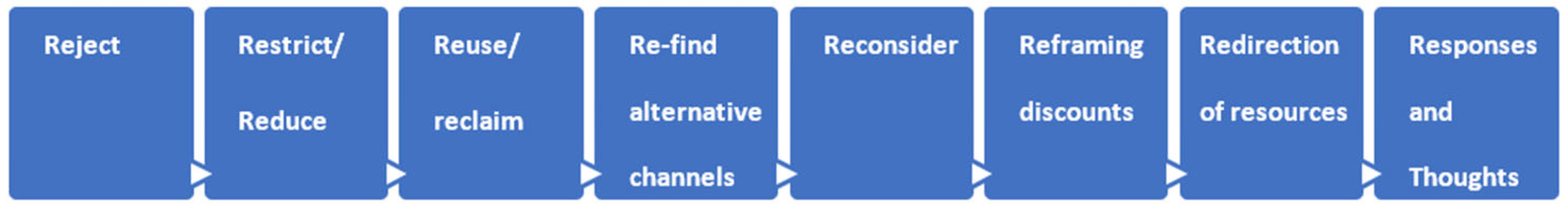

1.2. Developing the 8Rs Framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Voluntary and Non-Voluntary Anti-Consumerism

2.2. Economic Crisis and Anti-Consumption

2.3. Research Gap and Aim

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Reject

“I was going to buy a pair of pants for TL 200 one week, and when I went back a week later, it had gone up to TL 300. It’s like it went through a major price hike or something. I did not buy those pants.”(Participant 1)

“I used to buy new things not only to wear at work or outside but also to wear at home. I don’t buy clothes to wear at home anymore. I wear them even if they get old or torn.”(Participant 15)

“We’re in a crisis, and everyone knows it, but I think some sellers are unreasonably raising prices. Sometimes I vent my anger and get into arguments.”

“I’m definitely not going to the store right now because the prices in the store are much higher compared to the internet.”(Participant 2)

“I’m currently only shopping for what I need.”(Participants 2 and 4)

4.2. Restrict/Reduce

“It seems like we’re increasingly forced to compromise on the quality of the products we buy. For example, I find myself having to buy lower-quality items.”(Participant 6)

“I’ve reduced both the frequency of my shopping trips and the frequency of actually making purchases when I do go shopping.”(Participant 5)

“In the past, prices were not so exorbitant, and if I was between two colours in a product, I could buy both colours.”(Participant 10)

“I used to buy something for myself regularly every month, like 5-6 items in total. For example, if I bought a pair of pants in a pink colour, I’d get a matching white shirt and a matching bag to create outfits. However, unfortunately, I can’t do such combinations anymore, and I’m buying fewer pants now.”(Participant 7)

“Since the prices of the products have increased even more, I have to think even when buying a medium quality product. Sometimes when I see the products, even if I like them in style, I can say that I don’t need them anyway. In short, I am always careful not to buy everything I want.”(Participant 11)

4.3. Reuse/Reclaim

“Recently my shoe was torn, so I took it to the repair shop. It would have cost more to buy a new one.”(Participant 10)

“I didn’t use second-hand apps because why would I wear someone else’s clothes when there are no economic problems? But now I have to use them.”(Participant 2)

“I love Vakko bags, but I can’t buy them anymore, I think their prices have risen too much. Still, if I want that fashion icon bag to be mine, I buy second hand. I follow these second-hand applications and if there is a model of a bag that I like, I offer a price to the owner and try to buy it.”(Participant 7)

“I swap with friends or sell clothes I don’t use on social media or Facebook groups. I have to use these methods to avoid spending more as my income is not enough.”(Participant 13)

4.4. Re-Find Alternative Channels

“I usually browse items in the store and then purchase them online because they are generally cheaper on the internet. Even brands that appeal to a wide range of budgets tend to be more expensive in physical stores, while I can often find the same products online for a lower price.”(Participant 6)

“A new online shopping brand entered the Türkiye market (Temu). Everything is very cheap here. So, I immediately downloaded the application and started shopping here.”(Participant 15)

“When I know that I will wear a dress for only a few hours and only on special days, I don’t buy it because it is not rational. I rent instead.”(Participant 2)

“In the current economic conditions, there have been times when I borrowed clothes from my sister or close friends. But before the crisis, I would never have borrowed clothing from anyone. Before deciding to go shopping, we now often ask each other and take a look at each other’s clothes.”(Participant 10)

“There were things I wanted to buy but couldn’t, but I had my mom sew them for me.”(Participant 8)

“I have experienced bartering; if a friend has a dress I like, we can exchange it. This not only helps me to save my budget but also allows me to try something new. I also started doing DIY projects to renew my old clothes. For example, I redesigned an old T-shirt and sewed a little to make a new top.”(Participant 14)

“Previously, I used to shop only from well-known brands. However, now I also shop from small boutiques in the backstreets that may sell older items or may not necessarily follow the latest fashion trends. But in the past, I wouldn’t even consider shopping from such small, vintage-style stores.”(Participant 9)

“Nowadays, I go to open-air markets. In the past, I wouldn’t do my shopping at open-air markets but now I do because things are usually cheaper there.”(Participant 7)

“I sometimes ask my cousin who lives in Germany to bring me the shoes I’ve shown because it’s difficult to buy high-quality shoes here because of their prices.”(Participant 3)

4.5. Reconsider

“We inform each other about discounts in our group of friends and buy according to that. And because of the increase in shipping costs, we make purchases together from one account if only above a certain amount is eligible for free shipping. This way, we consolidate our shopping into one order to make it a free shipping.”(Participant 9)

“For example, when we are in the store with friends, we each look at different parts of the store. If we notice that an item has a good price or that it’s new, we can encourage each other to buy it. For example, “This would suit you, the price is very good, it looks like it’s new.””(Participant 3)

“I am planning a little more for the future. I am no longer thinking one step ahead but two or three steps ahead.”(Participant 10)

“I used to shop on a whim, but now I shop in a more conscious and planned way. Online shopping platforms have also helped me in this process. I can compare prices on different sites with a few clicks.”(Participant 12)

“I do a lot of price/performance comparisons now. I do a lot of research such as user reviews, evaluations of people who have bought it. I think about whether the quality, fabric, brand etc. is worth the money I will pay.”(Participant 7)

“For example, when I am looking for a t-shirt in a store, I think: “Is this really my style?” “How much can I use it in my daily life?” “Is the price more favourable than elsewhere?”. I also think, “Do I need to spend money on something else?””(Participant 13)

“It is necessary to turn that money into something tangible as soon as possible. The money one has in one’s hands has no value unless it is turned into something. It’s just a pile of paper. If I want to wear the money, I can’t. So, when I have money in my hand, if I need to buy clothes, I buy clothes.”(Participant 9)

“… sometimes I see something, and I buy it right away because I’m worried that I might have to spend more money on it in the future. So, in a way, I’m thinking ‘I should not miss this opportunity’ and I feel like I’m taking a precaution because I’m going to have to spend more money on this product in the future.”(Participant 8)

“I don’t want to buy a lot of clothes anymore, but I know that if I don’t, they will be more expensive tomorrow. So, when I need clothes the day after tomorrow, I will buy them more expensively. I have recently bought a few pieces of clothes just because of this.”(Participant 15)

“I don’t know what the future will bring. I often say, ‘I’m glad I bought it’ when I see that the price has gone up significantly the day after I purchased a piece of clothing.”(Participant 2)

“I now shop by thinking about the labour behind the items and their impact on nature. In this crisis, we can’t do much good for ourselves, let’s at least do good for nature.”(Participant 14)

4.6. Re-Framing Discounts

“Before, I didn’t care if there were discounts or not. Now, I wait for discounts, even though I might not find what I want, and I select from discounted items based on fit and size.”(Participant 5)

“I now save items I like on online shopping sites in my favourites. Adding items to favourites often prompts the site to offer discounts. When I receive discount notifications via email, then I plan my purchases.”(Participant 10)

“Due to the current crisis, products are in higher demand, and I want to get them before they potentially get more expensive. Waiting for discounts isn’t reliable anymore.”(Participant 3)

“I am excited to save money, but I am also worried about falling into the trap of buying things I don’t need just because they are on sale. That’s why I am very cautious about discounts.”(Participant 13)

4.7. Re-Direction of Resources

“I buy something more affordable on the second-hand applications and then resell the clothes I wear and buy something else I need.”(Participant 2)

“For example, I like to read books, so instead of buying books, I chose to become a member of the library. I can’t rent shoes, but I can rent a book for free from the library. So, I can buy clothes with the money I would normally spend on books.”(Participant 5)

“For example, if I need to buy shoes, I spend less that month by cutting back on other things. For example, I cut down on eating out or going to the movies so that I can afford the shoes.”(Participant 4)

4.8. Emotional Responses and Thoughts

“I’ve become better at managing money, calculating costs, and adapting to changing circumstances due to the crisis.”(Participant 6)

“When I shop, I question, “Will this really take up a place in my life?” I realised that I have too many clothes in my closet, and I don’t use many things. This situation has led me to a more minimalist lifestyle, and this is a good thing I guess.”(Participant 12)

“I am really tired of this economic crisis situation. The only thing I hold on to now is that I have somehow reduced my consumption a little bit in the age of fast consumption and so I have some benefit to the environment.”(Participant 14)

“Normally, I used to pay a lot of attention to my style of clothing because I think it reflects me and my different outlook on life. But now I may have difficulties in this regard. Sometimes, even though a product appeals to me very much, I may not prefer it because it is too high priced.”(Participant 11)

“I feel like I’m in a slump; not being able to shop frustrates me. Because our income falls short, I can’t fully engage in my work, and my motivation dwindles.”(Participant 2)

“I get really upset about the state of the economy, especially when young people should be enjoying their lives, buying what they want, but can’t, like us. It’s really frustrating. Plus, there’s a bit of fear due to the uncertainty. I am worried about what tomorrow will bring. I don’t know if something that costs TL 1 today will be TL 5 tomorrow, so it’s unsettling.”(Participant 10)

“I used to go shopping with my friends, but now I sometimes have to refuse them in order not to be embarrassed, in case there is something I want to buy but I can’t buy, and I make it known.”(Participant 15)

5. Discussion

5.1. Extending Anti-Consumption Theory: From 3Rs to 8Rs

5.2. New Contributions: Recession Rush and Re-Direction of Resources

5.3. Emotional and Functional Dimensions

5.4. Coping Strategies and Consumer Typologies

5.5. Interconnectedness of the 8Rs

5.6. Socio-Cultural and Individual Variations

5.7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aksoy Khurami, E., & Özdemir Sarı, Ö. B. (2022). Trends in housing markets during the economic crisis and COVID-19 pandemic: Turkish case. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 6(3), 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P. A., Wolf, M., & Kopf, D. A. (2010). Anti-consumption in East Germany: Consumer resistance to hyperconsumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(6), 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimen, N., & Bayraktaroğlu, G. (2011). Consumption adjustments of Turkish consumers during the global financial crisis. Ege Academic Review, 11(2), 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ang, S. H., Leong, S. M., & Kotler, P. (2000). The Asian apocalypse: Crisis marketing for consumers and businesses. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basci, E. (2014). A revisited concept of anti-consumption for marketing. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(7), 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Black, I. R., & Cherrier, H. (2010). Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: Daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(6), 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez, M., Henninger, C. E., Alexander, B., & Franquesa, C. (2020). Consumers’ knowledge and intentions towards sustainability: A Spanish fashion perspective. Fashion Practice, 12(1), 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, E., & Kirgiz, A. C. (2020). The effect of the 2018 economic crisis on purchasing behavior. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(3), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cici, E. N., & Özsaatcı, F. G. B. (2021). The impact of crisis perception on consumer purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 (coronavirus) period: A research on consumers in Turkey. Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 16(3), 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center, 17(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Elhajjar, S. (2023). Factors influencing buying behavior of Lebanese consumers towards fashion brands during economic crisis: A qualitative study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faganel, A. (2011). Recognised values and consumption patterns of post-crisis consumers. Managing Global Transitions: International Research Journal, 9(2), 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion United. (n.d.). Global fashion industry statistics. Fashion United. Available online: https://fashionunited.com/global-fashion-industry-statistics (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Francis, T., & Hoefel, F. (2018). True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies (Vol. 12, pp. 1–10). McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe Arpa, R. A. B. İ. Y. A. (2022). Tüketici Kimliği İnşasında Tüketim Karşıtlığı: Giyim Kültürü Üzerine Bir Araştırma [Doctoral dissertation, Karabük University]. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, N. (2020). Z kuşağı tüketicilerin satın alma karar tarzlarının incelenmesi. Yaşar Üniversitesi E-Dergisi, 15(58), 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, R., & Muncy, J. A. (2009). Purpose and object of anti-consumption. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S. A., & Furgerson, S. P. (2012). Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: Tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Roux, D., Cherrier, H., & Cova, B. (2011). Anti-consumption and consumer resistance: Concepts, concerns, conflicts and convergence. European Journal of Marketing, 45(11/12), 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. S., Fernandez, K. V., & Hyman, M. R. (2009a). Anti-consumption: An overview and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. S., Motion, J., & Conroy, D. (2009b). Anti-consumption and brand avoidance. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. S., Seifert, M., & Cherrier, H. (2017). Anti-consumption and governance in the global fashion industry: Transparency is key. In Governing corporate social responsibility in the apparel industry after Rana Plaza (pp. 147–174). Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar]

- Leipämaa-Leskinen, H., Syrjälä, H., & Laaksonen, P. (2016). Conceptualising non-voluntary anti-consumption: A practice-based study on market resistance in poor circumstances. Journal of Consumer Culture, 16(1), 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, X., & Yuen, K. F. (2023). Revenge buying: The role of negative emotions caused by lockdowns. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi, D., & Berler, M. (2018). Semi-structured interviews. In Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1–6). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Makri, K., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Mai, R., & Dinhof, K. (2020). What we know about anticonsumption: An attempt to nail jelly to the wall. Psychology & Marketing, 37(2), 177–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Labour and Social Security. (2024). Asgari Ücret. Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Labour and Social Security. Available online: https://www.csgb.gov.tr/poco-pages/asgari-ucret/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- O’Neill, B., & Xiao, J. J. (2012). Financial behaviors before and after the financial crisis: Evidence from an online survey. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 23(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdamar-Ertekin, Z. (2016). Conflicting perspectives on speed: Dynamics and consequences of the fast fashion system. Markets, Globalization & Development Review, 1(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ozdamar Ertekin, Z., Sevil Oflac, B., & Serbetcioglu, C. (2020). Fashion consumption during economic crisis: Emerging practices and feelings of consumers. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(3), 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C. V., Stylos, N., & Fotiadis, A. K. (2017). Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert-Stroescu, M., LeHew, M. L., Connell, K. Y. H., & Armstrong, C. M. (2015). Creativity and sustainable fashion apparel consumption: The fashion detox. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 33(3), 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, M. K. (2012). Postmodern Kimliğin İnşasında Televizyon Reklamlarının Etkisi. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343205855_POSTMODERN_KIMLIGIN_INSASINDA_TELEVIZYON_REKLAMLARININ_ETKISI (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S., & Naebe, M. (2020). Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Science of the Total Environment, 718, 137317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜİK. (2024). İstatistiklerle Gençlik, 2024. Turkish Statistical Institute. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Istatistiklerle-Genclik-2024-54077 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N., Lee, H. K., & Choo, H. J. (2020). Fast fashion avoidance beliefs and anti-consumption behaviors: The cases of Korea and Spain. Sustainability, 12(17), 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 8R | Definition |

|---|---|

| Reject | Actively avoiding or rejecting purchasing decisions due to high or rising prices, or questioning the fairness of price inflation during times of crisis. |

| Restrict/Reduce | Limiting or reducing consumption due to financial constraints, including cutting back on quantity or quality of purchases. |

| Reuse/Reclaim | The practice of using items more than once, either with minimal modification (Reuse) or repurposing them for entirely new uses (Reclaim), often driven by necessity or creativity. |

| Re-find | Seeking out alternatives or better deals, such as shopping in smaller stores, using price comparison tools, or looking for discounts and promotions to offset costs. |

| Reconsider | The internal process of re-evaluating wants and needs in light of financial constraints. Involves questioning whether a purchase is truly necessary. |

| Re-framing Discounts | Reinterpreting the value of discounts, where some consumers see discounts as a positive opportunity, while others view them sceptically, seeing them as a form of manipulation. |

| Recession Rush | The urgency to purchase items quickly due to the expectation of price increases, driven by economic uncertainty and fear of higher prices in the future. |

| Re-direction of Resources | The conscious reallocation of financial resources from one category of life to another (e.g., reducing leisure spending to afford fashion items). |

| (Emotional) Responses | Adjusting emotional reactions to purchasing and financial decisions, including dealing with feelings of guilt, excitement, or frustration, in response to economic pressures. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Argun, H.; Baxter, K.J.; Ni, A.K.; Ching-Pong Poo, M. When Money Gets Tight: How Turkish Gen Z Changes Their Fashion Shopping Habits and Adapts to Involuntary Anti-Consumerism. Businesses 2025, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030036

Argun H, Baxter KJ, Ni AK, Ching-Pong Poo M. When Money Gets Tight: How Turkish Gen Z Changes Their Fashion Shopping Habits and Adapts to Involuntary Anti-Consumerism. Businesses. 2025; 5(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleArgun, Hilal, Katherine Jane Baxter, Anna Kyawt Ni, and Mark Ching-Pong Poo. 2025. "When Money Gets Tight: How Turkish Gen Z Changes Their Fashion Shopping Habits and Adapts to Involuntary Anti-Consumerism" Businesses 5, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030036

APA StyleArgun, H., Baxter, K. J., Ni, A. K., & Ching-Pong Poo, M. (2025). When Money Gets Tight: How Turkish Gen Z Changes Their Fashion Shopping Habits and Adapts to Involuntary Anti-Consumerism. Businesses, 5(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030036