1. Introduction

The entrepreneurial mindset is an integral part of an entrepreneur’s role in entrepreneurial endeavors, business development, and innovation.

Ratten (

2023) offers a process-oriented definition of entrepreneurship and explains that the phenomenon is about identifying business-related opportunities by the entrepreneur or business owner through processes of new, existing, or recombined resources by being creative and innovative. It is also noted by

Nakajima and Sekiguchi (

2025) that entrepreneurs are involved in an ongoing process that surrounds their business development. Hence, there is an interplay between entrepreneurship and innovation with an individual element connected to actions and decision-making in the operationalization of the business. The relationship between process-oriented entrepreneurship and the entrepreneur’s role as an innovator was outlined earlier by

Schumpeter (

1942), where the author’s creative destruction is a process of activities connecting entrepreneurship and innovation, which affects the social and economic spheres of the market and the individual entrepreneur. The aforementioned entrepreneurial endeavors are related to business cycles, in which shorter and longer waves of business cycles occur and include temporal or spatial perspectives.

Schumpeter (

1939) explained that the entrepreneur’s role as an innovator is to see, feel, and take into account opportunities that might arise during the business cycle activities that connect entrepreneurship and innovation.

The process-oriented view of

Ratten (

2023) was also promoted by other researchers, such as

Chiles et al. (

2017),

Elia et al. (

2020),

Frese and Gielnik (

2023),

Goldsby et al. (

2024),

Nakajima and Sekiguchi (

2025), and

Nambisan (

2017), underlining the importance of organizational transformation, product and service development, business planning, psychology, growth, entrepreneurial actors, strategies, interactions and flows, along with the dynamic processes of entrepreneurship. Creativity and innovation are integral parts of entrepreneurship, as noted above, where it is further explained by

Castellacci (

2023) that innovation promotes and enables social welfare, while organizational and technological changes can develop and create opportunities that can improve human life. Thus, the authors posit that entrepreneurship is a process where different actions are undertaken over time by the entrepreneur, enabling the identification of opportunities that involve elements of innovation and creativity in entrepreneurship.

The entrepreneurial mindset phenomenon is a contemporary theme that has garnered attention in the academic fields of entrepreneurship and innovation during the last couple of decades, where scholars and stakeholders from different academic, business, and industry sectors have shown interest in the topic. The term “entrepreneurial mindset”, on the other hand, lacks a unified understanding and definition where a consensus exists among scholars (

Lynch & Corbett, 2023;

Mawson et al., 2023;

McLarty et al., 2023).

Kuratko et al. (

2021) explain that the entrepreneurial mindset has been studied from different research perspectives in recent years by utilizing entrepreneurship, innovation, or other academic fields, which has led to heterogeneous definitions of the term. Thus, different scholarly backgrounds have attempted to understand the phenomenon from their own epistemological perspectives and rationales, where the initial problematization surrounding the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial mindset is the different definitions and viewpoints that exist and interplay across various academic fields.

From the latter definitions, it can be noted that

Daspit et al. (

2023) and

McLarty et al. (

2023) consider the entrepreneurial mindset a cognitive perspective that can lead to value creation by the entrepreneur recognizing, identifying, and acting on opportunities. Moreover,

Pidduck et al. (

2023) focus on beliefs, where dispositional and opportunity beliefs interplay with each other.

Kuratko et al. (

2021) use perspectives to explain the entrepreneurial mindset, where the authors underline three key perspectives that interplay, namely the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects that the entrepreneur acts upon and engages in when opportunities arise. Subsequently, the abovementioned definitions of the entrepreneurial mindset can be reconnected to the entrepreneur’s role of seeing, feeling, and taking account of the opportunities that might arise during entrepreneurial endeavors, as noted by

Schumpeter (

1939), whereas different terminologies and nomenclature are used and have been developed over time. Earlier definitions can be found in studies by

McGrath and MacMillan (

2000),

McMullen and Kier (

2016), and

Shepherd et al. (

2010), where the authors focus their respective definitions on the ability or abilities of the entrepreneur and the willingness to identify, mobilize, act, sense, and exploit opportunities. Ultimately, the entrepreneurial mindset is viewed as a set of skills of static or fixed antecedents used by the entrepreneur to identify and capitalize on opportunities whilst conducting business. The understanding of the entrepreneurial mindset has developed over decades and still leaves room for exploring today’s challenges that involve technological innovations, resources, and external relations, which the entrepreneur should capitalize on.

The nexus of process-oriented entrepreneurship, which aims to identify opportunities, contrasts with the static entrepreneurial mindset, along with its perspectives and abilities, for the identification of opportunities by the entrepreneur to enable different outcomes. These do not align, as noted in the problematization above, and offer a research gap that demands further attention. Suggestions for future research also underline this interception, as

Kuratko et al. (

2021) highlighted the need to probe into the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects, along with the influences and factors that contribute to shaping the entrepreneurial mindset in different contextual settings.

McLarty et al. (

2023) add that the present outlooks, knowledge, and conditions regarding the entrepreneurial mindset—and how it is growing, developed, and maintained—can impact and affect vital economic considerations and outcomes in the long run. Ultimately,

Daspit et al. (

2023) also outline different research avenues, where the authors take on a broader approach to the entrepreneurial mindset and explain that future research can include process-focused, configurational, methodological, and multidisciplinary opportunities. Hence, several calls have recently been made for further advanced studies regarding the entrepreneurial mindset, focusing on the phenomenon in itself and the processes, operationalizations, contexts, dynamics, and opportunities surrounding the entrepreneur’s role.

By addressing the current research gap and problematization surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset, this study advances the established knowledge and maintains that future research regarding the entrepreneurial mindset should incorporate the phenomenon with its antecedents and outcomes along with the fluid circumstances and processes in which the entrepreneur finds themselves. The purpose of this bibliometric analysis is based on the abovementioned argumentation to explore the novelty surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset, offering new insights on a macro level, where the following three research questions are used in this study:

RQ1: What skill sets are needed for the entrepreneurial mindset?

RQ2: How is the entrepreneurial mindset practically operationalized?

RQ3: Where can opportunities be identified with the entrepreneurial mindset?

In order to answer the three research questions, there is a need to understand the fundamental components surrounding the theoretical framework of the entrepreneurial mindset, which is presented in the following section. Firstly, this is performed by outlining what skill sets are of importance for the entrepreneurial mindset, where the focus is on the antecedents that the entrepreneur needs to access, obtain, or acquire. Secondly, by moving from the traditional static approach of the entrepreneurial mindset to a more process-oriented view, it is imperative to recognize how the entrepreneurial mindset is practically operationalized during the entrepreneurial processes when the entrepreneur moves between antecedents and outcomes. Lastly, it is necessary to understand where opportunities can be identified from the actions of the entrepreneurial mindset, which contains different outcomes for the entrepreneur that can lead to value creation.

This study undertakes a bibliometric analysis of the entrepreneurial mindset to answer the three research questions, address the current research gap, and advance the current research frontier. This approach can offer an added spectrum of nuances regarding what is known, which novelty can be identified, and how it can contribute to the academic field. Earlier research has been oriented towards different types of reviews on the micro and meso levels, mainly literature reviews that can be found in

Daspit et al. (

2023) but also previously in

Larsen (

2022) and

Naumann (

2017). Hence, less attention has been given to bibliometric review types, which opens the possibility of conducting this type of research on a macro level. Subsequently, this bibliometric analysis offers a new approach on a different aggregate level than earlier reviews to synthesize the established knowledge base.

The introduction to this study will be followed by a theoretical outline of the entrepreneurial mindset, a section containing the methodological approach, and then the findings. The research paper ends with a discussion, implications, and suggestions for future research.

3. Methodological Approach

The methodological approach in this research paper is a bibliometric analysis, which is based on the guidelines and procedures from

Donthu et al. (

2021), where inspiration and insight is taken from

Broadus (

1987),

Kessler (

1963),

Lim et al. (

2024),

Perianes-Rodriguez et al. (

2016), and

Zupic and Čater (

2015) to answer the three research questions. Due to the three research questions covering a wide range of possibilities and opportunities surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset, a bibliometric analysis offers large quantities of data to summarize and present the current emerging trends and intellectual structure of the research field, according to

Donthu et al. (

2021), where the authors add that this is an appropriate methodological approach when there is a broad scope to review and where the available data are too vast to manage and review manually. Hence, a macro-level approach to the entrepreneurial mindset, as in this research paper, benefits from the possibilities of bibliometric analysis as a methodological approach. Moreover,

Donthu et al. (

2021) explain that large data sets, broad scopes, and quantitative analysis with a focus on evaluation and interpretation, as well as qualitative analysis with a focus on interpretation only, are possible with bibliometric analysis.

The toolbox of bibliometric analysis consists of two main techniques, performance analysis and science mapping, as well as an enrichment technique based on network analysis (

Donthu et al., 2021). The performance analysis consists of citation-related metrics, publication-related metrics, and citation-and-publication-related metrics, whilst science mapping consists of bibliographic coupling, citation analysis, co-citation analysis, co-authorship analysis, and co-word analysis, according to

Donthu et al. (

2021), whereas the network analysis consists of clustering, network metrics, and visualization. Hence, a certain set of possibilities and opportunities for analysis exists that the researcher can navigate through in order to answer the research questions. Moreover,

Lim et al. (

2024) offer guidelines and directions for the use of techniques for analysis, which have been adopted to be systematic throughout the research in this bibliometric analysis.

Zupic and Čater (

2015) also add that each technique applied from the arsenal of bibliometrics analysis has its advantages and disadvantages, which the researcher needs to reflect, argue, and decide on.

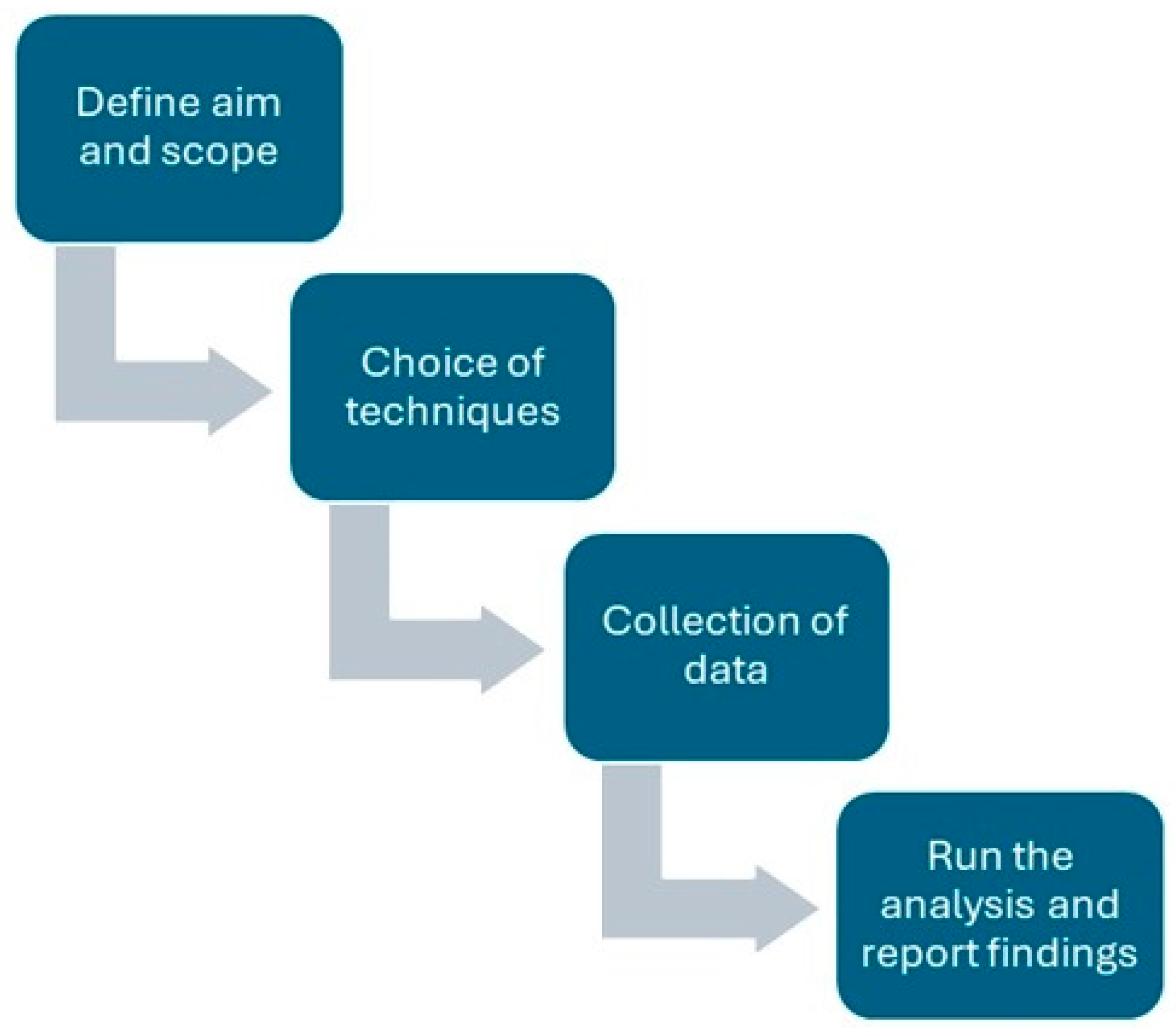

The procedure of the bibliometrics analysis in this research paper is based on the four steps by

Donthu et al. (

2021), which are the (i) definition of the aim and scope, (ii) choice of techniques, (iii) collection of data, and (iv) running the bibliometric analysis and report the findings, as visualized in

Figure 1.

Donthu et al. (

2021) explain that the first step is two-fold, where apart from defining the aim and scope, it is also necessary to have a definition that is broad and wide enough to warrant and argue for the practical use of bibliometric analysis in the research. The second step is, as explained above, focusing on choosing appropriate and suitable techniques based on the defined aim and scope of the research. The third step consists of designing the research terms based on the aim and scope along with selecting databases that are adequate for the bibliometric analysis, which is derived from the first step, according to

Donthu et al. (

2021), whereas retrieving the data based on the second step and then remove duplicates, errors and clean the data before proceeding. The fourth step is divided into the bibliometric analysis techniques that are previously outlined and lead to the results and curation of a summary of the findings, a discussion, and the research implications (

Donthu et al., 2021).

The practical work with the methodological approach started with defining the aim and scope of this bibliometric analysis, which culminated in three separate research questions in accordance with

Donthu et al. (

2021). Due to the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial mindset being given less attention to the topic on a macro level, as outlined in the earlier sections, there is a research gap that can be further studied and provide novelty to this research paper. Since this research paper has three different research questions, both evaluation and interpretation are needed for the upcoming analysis, where the analysis approach is quantitative to include the broad scope and large database set. Subsequently, the choice of techniques relies on the main technique of science mapping and is complemented with the enrichment technique of network analysis to have a quantitative approach that includes both evaluations and interpretations in the analysis part (

Donthu et al., 2021;

Lim et al., 2024;

Zupic & Čater, 2015). This was followed by the collection of data where databases offered by the university library were used in this research paper with their unique profiles that scan and cover broad types of subject areas, publishers, citations, journal storages, along with general and multidisciplinary types, due to the entrepreneurial mindset being part of various academic fields and disciplines. The profiles of the database search for the collection of data are found in

Table 1 below, along with the database name, type of database, date of extraction, search words, and number of hits in each database.

Since the entrepreneurial mindset can be found and identified in different academic fields and disciplines, a total of seven databases were chosen and consist of different types that include a vast number of fields of study types and are multidisciplinary. The search words used in each of the databases include the term entrepreneurial mindset, where citation marks were utilized in accordance with the technical options provided by the respective database to center the search on the phenomenon. Moreover, the database search focused on the search words being used in the title, abstract, or keywords since this bibliometric analysis aims for the entrepreneurial mindset to be the primary study object and not a secondary term found in appendices, reference lists, or other texts. Hence, the included studies in this bibliometric had to be academic articles and meet the following three criteria in each case: be peer-reviewed, be written in the English language, and contain the search words. Ultimately, all the previously mentioned inclusion criteria had to be met for the academic articles to be included in the bibliometric analysis. The total number of articles identified in the first search was 1053, and the date of the data extraction was 6 July 2024. After removing duplicates, the final number of articles was 478 in this bibliometric analysis, where the oldest article is from 1991. In the final step, the analysis was run in the software program VOSviewer and will be presented with visualizations in the upcoming section, where the reporting of the findings will be found, in accordance with

Donthu et al. (

2021) and the guidelines from

Lim et al. (

2024). Albeit there are other software programs that can be used, as highlighted by

Donthu et al. (

2021), this research paper relies on VOSviewer due to this methodological approach being used to aid the research with its aim and scope in answering the research questions. Subsequently, from the main and enrichment techniques that were chosen in earlier steps, the bibliometric analysis was centered on and narrowed to network and overlay visualizations to meet the defined aim and scope of the research paper and to answer the research questions. The bibliometric analysis consisted of co-occurrences of words and fractional counting with at least one occurrence, which led to 237 hits and a total of 180 co-occurrences that are visualized below. The benefits of co-occurrences rely on the number of occurrences of the keyword, the link between keywords, the number of times the occurrences happen, the size of the occurrences, and the number of links of the occurrences (

Donthu et al., 2021). Subsequently, the benefits of fractional counting rely on the notion that each action, such as publications or links, is given equal weight in order not to have a single keyword being re-used and given a greater impact in the bibliometric analysis (

Perianes-Rodriguez et al., 2016).

Donthu et al. (

2021),

Lim et al. (

2024),

Perianes-Rodriguez et al. (

2016), and

Zupic and Čater (

2015) explain that there are limitations associated with bibliometric analysis which includes the extraction of data since the databases are not solely made for bibliometric analysis, along with limitations found in either having qualitative or quantitative analysis approaches, as well as the forecast from the bibliometric analysis is short term oriented, whereas the researcher ought to be aware of the long term implications changing and varying while discussing the findings. For the transparency of this research paper, and its reasons for reliability and validity, the author has considered the limitations and presents the shortcomings openly when they occur, which can eventually be addressed in future research.

4. Findings

The findings in the bibliometric analysis are dual and consist of two parts, which will be presented in this section. The first part covers the evaluation of this bibliometric analysis, whilst the second part focuses on the interpretation, which is in accordance with the outlined methodological approach in the former section. Subsequently, the first part will have its foundation in a network analysis whilst the second part will contain an overlay analysis where both the main and enrichment technique is used for the respective parts of the findings.

The bibliometric analysis has keywords that occur in different frequencies and with a heterogeneous profile, which form clusters that can be seen in the following network and overlay analysis. A first indication of the keywords and their occurrences can be found in

Table 2, where the keywords with the ten most occurrences are presented and enable an overview of the interplay and setup of the main keywords in this research paper. The term entrepreneurial mindset has the highest number of occurrences, a total of 21, and is followed by the keywords of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education with 16 occurrences each, whereas all of the most frequent keywords have at least five occurrences, respectively. A further detailed description of the keywords in this bibliometric analysis is provided below.

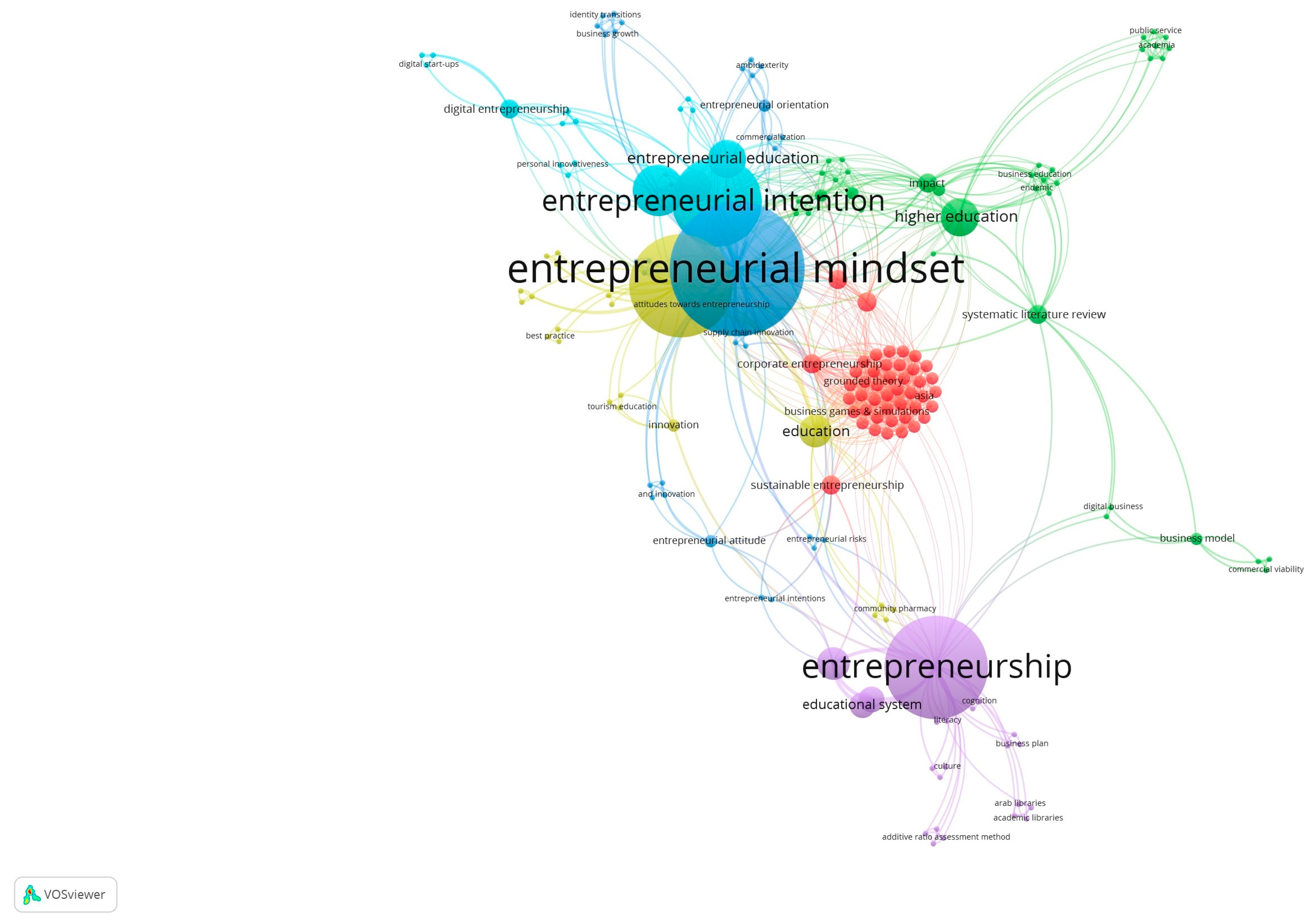

The network analysis can be found in

Figure 2 below and highlights the co-occurrences of color-coded words that can be sorted into six different clusters. As noted in the evaluation of the visualization, the entrepreneurial mindset is the main cluster in blue color, whereas the other clusters have less attention but can be classified into different keywords and the identification of themes through the interpretation of the visualization. Moreover, some of the clusters dominate certain keywords or themes, whilst others are more stratified with outliers where the keywords and themes are balanced and utilized differently. Hence, from the evaluation of the visualization, there is a heterogeneity in the network analysis that aligns with the entrepreneurial mindset’s theoretical framework, which demands further interpretation of the findings.

The clustering of the findings in the network analysis is found in

Table 3, which includes keywords and identified themes. The core cluster is the entrepreneurial mindset, which is followed by the identified themes of entrepreneurship in purple, entrepreneurship education in yellow, entrepreneurial intention in turquoise, higher education in green, and lastly, a cluster in red labeled “the missing dynamics” in this research paper. The clusters are notably moving from a homogenous collection of keywords within the themes to more variety and assortments, where some of the keywords are found in several clusters whilst others are isolated, new, or outliers in the visualization.

Notably, in the findings, three different keywords connect the entrepreneurial mindset’s core cluster with the other clusters, apart from the missing dynamics cluster. The first keyword is innovation, which is found in the entrepreneurship education cluster as well as in the entrepreneurial intention cluster as innovativeness. The second keyword is based on business, including business growth, business plans, and business models, which is found in the core cluster, along with the entrepreneurship and higher education clusters. The final keyword is behavior, which connects the core cluster with the clusters of entrepreneurial intention and higher education.

When focusing on the keywords, the missing dynamics cluster is mainly detached from the other clusters with no direct keyword connections. Moreover, as the clusters become more heterogeneous, the number of keywords also expands and increases quantitatively, including interdisciplinary terms and embedded associations into the already-outlined clusters. Hence, this creates a dynamic in the last cluster where there is a mix of interdisciplinary and embedded keywords, which offers, enables, and highlights another dimension of the entrepreneurial mindset that is less connected to the theoretical framework.

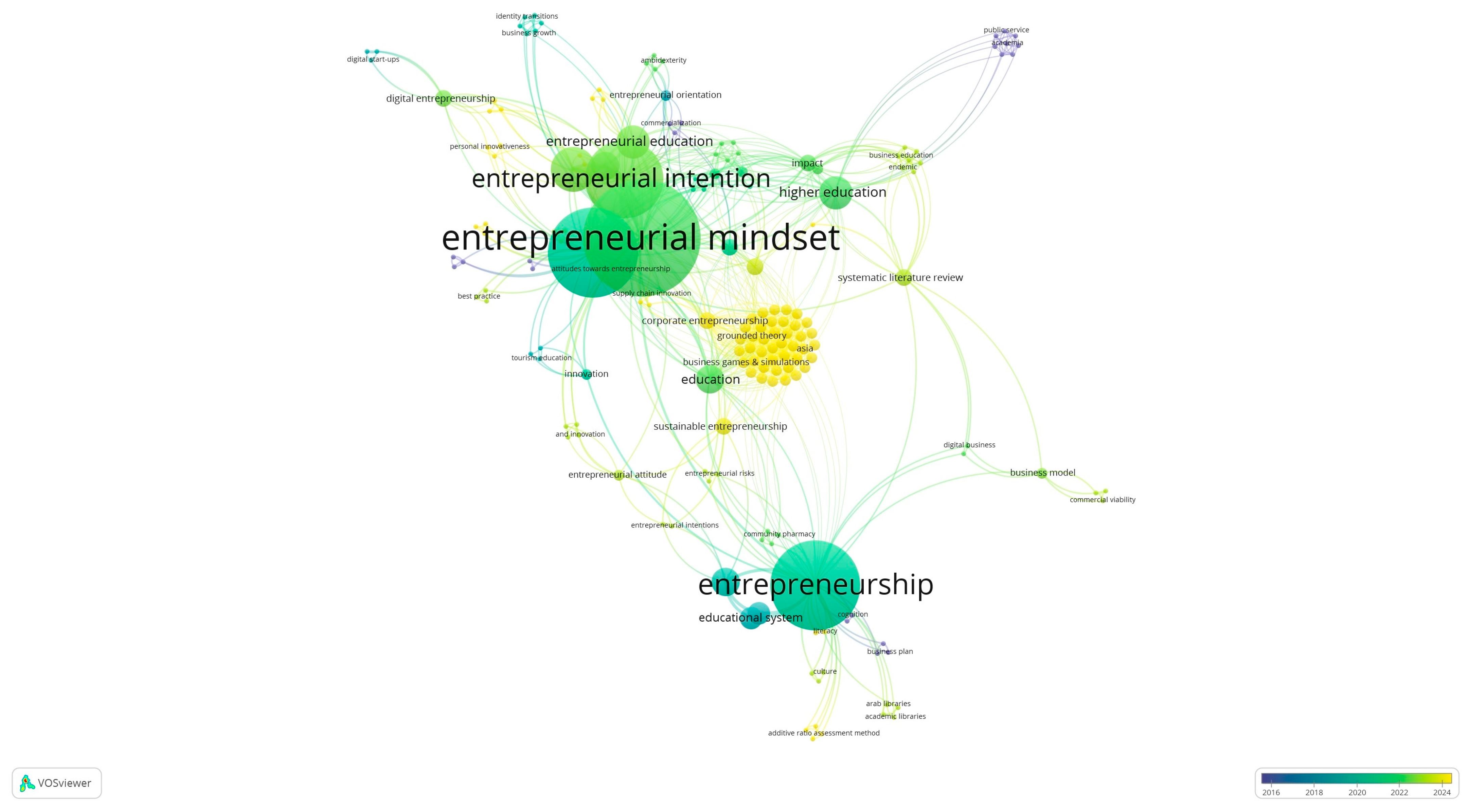

The overlay analysis is found in

Figure 3 and focuses on the development and progress of the entrepreneurial mindset during the last years with time scales that are color-coded in navy, green, and yellow and chronologically presented. The time scales are inspired and based on business life cycles by

Schumpeter (

1939), where the shortest wave is about three years. Hence, the overlay analysis is divided into three stages: an early stage in navy color, an intermediary stage in green color, and a recent stage in yellow color, where each stage covers three years, which backtracks and aligns with the shortest wave of business cycles.

The network analysis is used as a foundation and template for the overlay analysis, where the different clusters are colored in a scheme that highlights the time scales of co-occurrences of words that have been conducted and enables a view that incorporates a spectrum of changes and advancements to the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial mindset during the last years. Hence, the overlay analysis indicates development and progress that has matured over the last years, whereas the core cluster of the entrepreneurial mindset has been the focus of the studies in this bibliometric analysis, and notably, there are only a few co-occurrences that are recent and outliers of the matured clusters.

However, the cluster that has been labeled “the missing dynamics” from the clustering in the network analysis has, in this overlay analysis, an exclusiveness in being new and recent in the studies with fewer connections to the other clusters, as previously noted in the network analysis. Hence, the whole cluster of the missing dynamics has seen its development over the last months from the data extraction and leaves room for even more evaluation and interpretation to further understand and explore the entrepreneurial mindset as a phenomenon, along with opening up new research avenues.

The development and progress during the last years, which have been presented in the overlay analysis, are divided into a time scale to highlight the changes and adaptions to the entrepreneurial mindset, which can be seen in

Table 4. The time scale focuses on the early stage of development, the intermediary stage of progress, and the most recent stage, which is the current and contemporary state of the entrepreneurial mindset.

It is noted that the early stages of the development of the entrepreneurial mindset are today in the periphery and mostly outliers to the clusters. This is followed by an intermediary stage, which focuses on the core cluster of the entrepreneurial mindset but also on the clusters of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intention, and higher education. The intermediary stage contains most of the clusters in this bibliometric analysis. Lastly, the recent stage is attached to the missing dynamics cluster and outliers to the already-established clusters.

Notably, both the network analysis and the overlay analysis highlight a combination of static or fluid views and approaches of the entrepreneurial mindset, which can be noted on the aggregated macro level that this bibliometric analysis enables. Hence, the findings indicate that the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial mindset has developed and progressed over the years but still leaves room for further exploration and research with a focus on the missing dynamics cluster and the outliers, which are the most recent adaptions and changes to the entrepreneurial mindset and demand additional attention.

5. Discussion

There are several points to be discussed in this section, such as where the findings align with or deviate from the theoretical framework and enable nuances regarding what is known, which novelty can be identified, and how it can contribute to the academic field. The discussion will provide answers to the three research questions in this research paper. Moreover, both novelty but also already established knowledge can be outlined from the findings and add to the current research frontier with new suggestions for future research.

From the findings, it is noted that the cluster of the entrepreneurial mindset aligns with the theoretical framework when it comes to antecedents and outcomes. This is primarily connected in the form of the entrepreneurial mindset triad, where cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects make up skill sets for the antecedents, in accordance with

Kuratko et al. (

2021). On the other hand, the outcomes are venture and business-oriented, where opportunities can be identified, as noted by

Daspit et al. (

2023). Moreover, keywords such as innovation, business and behavior connect the entrepreneurial mindset to the other clusters, apart from the missing dynamics, where common ground can be identified and reconnected to the theoretical framework which covers the antecedents and outcomes of various extents (

Goldsby et al., 2024;

Kuratko et al., 2021;

Pidduck et al., 2023). Hence, the core findings in this bibliometric analysis align with already established knowledge, which is outlined in the theoretical framework section, surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset.

The second cluster of entrepreneurship also aligns with the theoretical framework but is more oriented towards outcomes and processes. The duality of assessments, where

Daspit et al. (

2023) focus on hard measures and values for the outcomes, which can eventually be quantified, whilst

Pidduck et al. (

2023) use soft measures and values which are qualitative, whereas both can be identified in the findings and enable opportunities for the entrepreneurial mindset. Moreover,

Ávila-Robinson et al. (

2022),

Frese and Gielnik (

2023),

Martin (

2016),

Nakajima and Sekiguchi (

2025), and

Ratten (

2023) have highlighted processes in entrepreneurship and its endeavors, which this cluster also has fragments of and could benefit from further studies. Subsequently, identifying opportunities by the entrepreneur, which the entrepreneurial mindset has as a possible outcome, can be attached to the context or milieu of which entrepreneurship enables and provides to the individual entrepreneur.

The cluster of entrepreneurship education is mostly process-oriented in the findings, where the focus is on several soft measures and values, such as learning, best practice, health, and training, which can be connected to

Pidduck et al. (

2023) and the circularity and feedback loop that the authors highlight. Hence, the entrepreneurship education cluster aligns with the process-oriented view of entrepreneurship that

Ratten (

2023) utilizes. However, this cluster also has a well-being and work–life balance approach, which deviates from the current theoretical framework and demands more attention. However, there is an emotional and well-being element in the outcomes of the entrepreneurial mindset and the context of the individual but not concerning processes, which can be further explored (

Binder & Blankenberg, 2017;

Kuratko et al., 2021;

Mawson et al., 2023). By further exploring the cluster of entrepreneurship education, new perspectives on the entrepreneurial mindset, such as the well-being and work–life balance of the entrepreneur, can be further understood, measured, and explored.

The fourth cluster, entrepreneurial intention, is linked to the antecedents, but the theoretical framework has given less attention to the intentions of the entrepreneur in comparison to other clusters.

Barth et al. (

2017) have explained that the entrepreneur, manager, or business owner can have value intentions at the early stages of the entrepreneurial endeavor, but this argumentation demands more attention in order to understand the connections to value building blocks, innovation, and attitudes during business developments. Similarly,

Akbari et al. (

2024),

Pinto et al. (

2024),

Seoke et al. (

2024) and

Zemlyak et al. (

2022) also argue for entrepreneurial intention as a key part of the entrepreneurial mindset when it comes to intentions, self-esteem, self-efficacy and motivations of the entrepreneur or business owner. Both

Daspit et al. (

2023) and

McLarty et al. (

2023) have indicated that value creation can be enabled by the individual entrepreneur remaining adaptable in complex situations, which can be further explored in relation to the entrepreneurial intention that the entrepreneur has. Hence, this cluster leaves room for further studies that can be connected to business growth, business plans, and business models, as noted in the findings section regarding keywords that link the clusters.

Moreover, the cluster of higher education is peripherical in the findings and has outliers also that are at the early stage of the time scale, which can be a sign of the cluster having saturated and matured enough and not offering as much value, originality, and novelty as before. This can be reconnected to business life cycles and that the cluster is declining, which can be in favor of other clusters surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset that are emerging (

Patricio & Ferreira, 2024;

Schumpeter, 1939). However, this cluster has several similarities to the cluster of entrepreneurship education, with its process-oriented alignments, but is more general and static in its orientation and substance. Hence, fragments of a process orientation can be noted, in line with

Daspit et al. (

2023) and

Pidduck et al. (

2023), but this cluster has fewer co-occurrences to highlight and could be on the decline, which the overlay analysis also visualizes. Subsequently, the higher education cluster could be of less interest to further study.

The final cluster of this bibliometric analysis, which has been labeled “the missing dynamics”, has few connections to the theoretical framework and cannot be clearly sorted into antecedents, processes, or outcomes of the entrepreneurial mindset. Several keywords that the missing dynamics cluster consists of, such as sustainability, hybrid, youth, doubt, journey, and perception, have little, modest, or no relation to the theoretical framework surrounding the entrepreneurial mindset. However, the keywords can be contextualized and explained with examples such as the level of sustainability changing over time, having a journey that is ongoing or doubt being turned into certainty, which can be connected to processes, but not directly to the views presented amongst the entrepreneurial mindset literature (

Daspit et al., 2023;

Pidduck et al., 2023). Moreover, this cluster has explicitly grown over the last months before the data extraction in this study and offers many interesting ideas and opportunities for future research, where the novelty identified in this research paper can be further explored and given attention to from different academic fields.

Reconnecting to the three research questions, this bibliometric analysis of the entrepreneurial mindset has provided both validation of what is already established in the academic topic and offered novelty that can be a stepping stone for future research on a topic still emerging. Looking at what skill sets are needed for the entrepreneurial mindset, it is already a close alignment to the already established theoretical framework, but an addition can be found in the entrepreneurial intention. This skill set could create value for the entrepreneur and eventually be integrated with the entrepreneurial mindset and its antecedents. Hence, an integration of entrepreneurial intention into a framework or conceptualization of the entrepreneurial mindset could enhance and utilize the phenomenon.

The second research question, regarding how the entrepreneurial mindset is operationalized practically, offers a dual answer from the findings. Firstly, the theoretical framework gives less attention to the processes of the entrepreneurial mindset, but this bibliometric analysis highlights that processes are an integral part of the entrepreneurial mindset and can be noted in the network analysis, which aligns with views of entrepreneurship by

Ratten (

2023). Secondly, how the operationalization is practically enabled and achieved is not explained in this bibliometric analysis, but the cluster of the missing dynamics has several process-oriented perspectives that demand more attention, especially as the overlay analysis emphasizes its recent emergence. Hence, the entrepreneurial mindset can be operationalized practically by further exploring the missing dynamics and understanding the interplay of keywords, such as sustainability, hybrid, youth, doubt, journey, and perception, with what is already known regarding the entrepreneurial mindset to advance and expand the current knowledge base. Moreover, there is a possibility to further explore the measurements and assessments of the operationalization to have quantitative or qualitative comparisons or benchmarks.

When it comes to where opportunities can be identified with the entrepreneurial mindset, alignments can be found with the outcomes of the entrepreneurial mindset. However, less novelty is found in this argumentation. Instead, it is possible to underline the importance of practices that can balance entrepreneurship education and higher education, which is part of the entrepreneurial mindset. Subsequently, this bibliometric analysis has a heavy orientation towards the cluster of entrepreneurship, where it is noted that the opportunity identification is mainly in the practical work of the entrepreneur, the entrepreneurial endeavors, and the business or venture. Hence, with its entrepreneurial endeavors, the need for entrepreneurship is key for the entrepreneurial mindset to have a context or milieu in which to exist and thrive for the entrepreneur to identify opportunities and achieve new value creation.

6. Implications

The implications of this bibliometric study are centered on the alignment of the entrepreneurial mindset with processes that can enable value creation for entrepreneurship. As noted previously,

Ratten (

2023) outlined that entrepreneurship is process-oriented, and having a transition from a static to a more fluid, dynamic, and operationalized entrepreneurial mindset can lead to new opportunities that can be identified by the entrepreneur and, in turn, yield value creation. The bibliometric analysis has aligned with the antecedents of the entrepreneurial mindset, in accordance with

Kuratko et al. (

2021) and the entrepreneurship mindset triad, but has the possibility to expand further to include intentions, as discussed in the former section, which would align with

Barth et al. (

2017). Hence, enabling or constructing a concept of moving from a triad to a quadrant of the entrepreneurial mindset could be of interest to observe and explore.

The processes of the entrepreneurial mindset have received scant interest earlier, even though entrepreneurship is a process-oriented field (

Ratten, 2023). This bibliometric analysis underlines that processes are part of the entrepreneurial mindset, whilst there is also a cluster that highlights several process-oriented factors that demand more attention to further advance the research regarding the entrepreneurial mindset. By examining and delving into the operationalizations surrounding phenomena such as sustainability, innovation, work–life balance, or inclusiveness of entrepreneurs, the entrepreneurial mindset has the potential to further develop, progress, and adapt. This can be related to the keywords of innovation, business, and behavior, which connect most clusters and can eventually be transferred to the missing dynamics cluster. The implications surrounding the process-oriented view of the entrepreneurial mindset, as revealed by the findings of this bibliometric analysis, offer the possibility and opportunity to enhance our understanding of the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial mindset.

The outcomes of the entrepreneurial mindset align with the theoretical framework with an emphasis on the practices of entrepreneurship. The bibliometric analysis shows the importance of the entrepreneurial mindset for the outcomes, and this can further be sorted and divided into hard or soft measures, assessments, and values, which aligns with

Daspit et al. (

2023) and

Pidduck et al. (

2023) and can offer further research possibilities. Having a context or milieu, which is provided by entrepreneurship, enables the entrepreneurial mindset to thrive and for the entrepreneur to identify opportunities that can lead to new value creation, overcoming challenges surrounding technological innovations, resources, and external relations.