1. Introduction

Due to its reliance on personalized service, the hospitality industry was among the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2019, especially through 2020 and 2021. Previously, high-touch, high-contact, and personalized service delivery was a hotel’s source of strength. During the pandemic, these selling points of customer service became possible virus transmission pathways. They needed to be managed to mitigate health risks [

1]. Thus, the pandemic accelerated the adoption of innovative technologies such as service robots, wearable interfaces, face recognition, and smartphone apps. These tools were used to provide pandemic prevention and as a means of remaining competitive [

2,

3,

4]. Some organizations created specialized units specifically for the purpose of identifying and incorporating emerging technology into their business operations and managed to capitalize on the new e-opportunities [

5]. Conversely, hotels that did not adjust swiftly to the changes in the external environment found themselves unable to maintain viable operations and invest in innovation [

1,

6].

Customer preferences also changed. For example, Xu et al. [

7] found that concerns about hygiene had become a prevalent theme in hotel guest reviews. A study of customer perceptions similarly showed that 40 percent of hotel patrons put a very strong emphasis on safety and hygiene measures [

8]. Customer support for innovation that improves operational efficiency (e.g., keyless entry) also increased [

9,

10].

Organizations that incorporated pandemic prevention measures into their operational models were expecting a more robust economic recovery [

11,

12]. However, new technology was often introduced hastily and without strategic consideration [

13]. Adoption barriers such as staff resistance to operational innovation had an adverse effect on the hotel’s ability to benefit from the adoption of new technology [

11] and extract business value [

14].

According to Bonanomi [

15], most digital transformation strategies fail because organizations prioritize implementing the latest software and tools without managing their impact on people, processes, and the organizational culture. Oikonomou et al. [

16] also point out that operational changes related to innovation need to be aligned with the technological capabilities of hotel employees and with customer expectations, while, at the same time, meeting the strategic objectives of the organization.

Employee capabilities such as technological expertise form the bedrock for successful digital transformation [

5,

16]. Among these, the information technology (IT) expertise and innovation capability of hotel managers and owners are among the significant drivers of IT adoption [

17]. For example, the strong technology-centric orientation of some established international hotel chains allowed them to capitalize on organizational knowledge and experiences and respond quickly to the pandemic crisis by enhancing service quality [

18].

However, new technologies may disrupt traditional hospitality operations as they change operational models and affect customer relationship management [

19,

20]. For example, innovations such as touchless solutions require a thorough technological integration with existing systems while also ensuring that the technology does not wholly depersonalize the guest experience [

21]. Thus, a number of managers (mainly of smaller hotels) remained hesitant to accept the risk associated with investing in and adopting new technology. They continued to adhere to pre-pandemic service norms [

22] despite increased customer expectations for services that incorporated health and safety practices [

7,

23].

There is a significant body of research literature on the adoption of new digital technologies in the hospitality sector. Earlier research investigated how technological innovation was used to satisfy new information needs [

24], with the main focus on technological quality and compatibility [

25]. More recent empirical research has retained a focus on customer experiences and has also investigated the impact of technological innovation on value creation, the competitive advantage, and the organization. For example, Ndhlovu et al. [

26] point out that the adoption of digital tools significantly affects the welfare of hotel employees as staff fear job losses and displacement. Furthermore, negative perceptions about the value of the digital change and how it affects one’s job foster moral disengagement and can lead to unethical staff behavior [

27].

The roles of hotel employee perceptions, attitudes, and digital skills as factors in the adoption process have not been examined in significant depth [

28,

29]. Some studies have suggested that embedding new technology adoption in a managed change process may help organizations pave the way for an effective and enduring business process integration and successful digital change [

30,

31]. Still, relatively few researchers have investigated technology adoption and continued technology use through the lens of change management [

14].

Research on technology adoption strategies and entrepreneurship is also limited [

32]. Park et al. [

33] conclude that current research on innovation in the hospitality industry views technology predominantly as a method of service delivery and suggest that future research should also consider the associated managerial and institutional innovation processes.

This study addresses the gaps identified by providing a theoretical conceptualization of the stages of technological innovation, from initial technology acceptance to continued use. It views technology adoption as a ‘strategic opportunity to create and consume growth options’ [

32]. The research question is formulated as follows: How can hotel organizations synergize technological, entrepreneurial, and managerial dynamics to achieve effective digital innovation? To address the research question, this study reviews the relevant literature and proposes a process framework for the management of technology adoption in the hospitality industry.

Although successful digital innovation is seen as the driver of the ongoing process of digital transformation in the hotel industry [

32,

33], studies suggest that digitalization and technology adoption in the hotel sector are still in their infancy [

23,

33,

34]. This study demonstrates how managing technology adoption from the perspective of organizational change can help the organization identify, select, and adopt new technologies that are strategically important and realize their benefits for achieving successful digital innovation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section reviews the literature on models and theories in the areas of technology adoption, entrepreneurship, capability building, and change management and provides hospitality-related examples to illustrate the relevant concepts. The findings of the literature review are synthesized in

Section 3, which describes the proposed DEAC (detection–engagement–agility–continuity) framework and brings in two case studies.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the framework and the contributions and the limitations of this study. Directions for further research are also proposed.

2. Technology Adoption, Entrepreneurship, and Change Management in Hospitality Research

Technology, and more specifically IT, has the potential to initiate innovation across products, services, and operational procedures. Service organizations such as hotels adopt new technologies as a means of responding to external change and remaining competitive [

35]. As innovation is implemented as a ‘bundle’ across one or more innovation categories (e.g., services) [

33], it leads to changes to a broad range of operational processes. The organization needs to adapt to the innovation bundle and ensure both efficient service delivery and accelerated capability building [

36,

37,

38]. The proposed DEAC framework builds on the concept of applying a change management approach to the adaptation process to ensure effective and seamless technology adoption [

39].

To develop the theoretical foundation of the framework, this section reviews concepts and models related to technology adoption, capability building, entrepreneurship, and change management. These are examined in the context of the hospitality industry.

2.1. Modeling Technology Adoption in Hospitality

In the hospitality industry, technology adoption has been acknowledged as an effective risk-reduction strategy [

40]. For example, during the pandemic, self-service technologies (SSTs) were used to minimize contact and enforce social distancing as a means of alleviating the health risk [

41]. The technology’s perceived value to key external stakeholders (e.g., customers) [

10,

42] also influences the decision on whether it is adopted. For example, customers tend to accept technology they find useful in a specific use context, e.g., contactless payment in situations where the risk of infection is high [

6,

9]. In addition, technologies that are easy to use (e.g., SSTs) are more likely to be perceived as useful and acceptable [

10,

43].

Perceived usefulness and ease of use are the two independent variables of the technology acceptance model (TAM) [

44]. The model captures the dynamics of technology adoption by postulating that user perceptions about technology usefulness and ease of use are the ultimate factors influencing the intention to use technology, eventually leading to full technology acceptance. TAM and models derived from it have been used extensively in hospitality research [

33].

Internal stakeholders (e.g., employees) are also part of the adoption process as the new technology is integrated in their daily tasks and job routines. Misconceptions about the purpose of the new technology, failure to communicate the importance or the urgency of the adoption, as well as inadequate training and upskilling may result in developing a resistance to change and slowing down the technology adoption process [

23].

TAM2 was developed by Venkatesh et al. [

45] and incorporates factors that are external to the technology itself but play a role in the adoption process. The model extends TAM by including two new constructs: social influence and cognitive instrumental processes. We discuss these below and illustrate them with examples from the hospitality industry.

2.1.1. TAM2: Social Influence Processes

The TAM2 variables related to social influence processes are the subjective norm, image, experience, and voluntariness. The subjective norm and image are the antecedents of perceived usefulness (moderated by experience). The subjective norm also directly influences the intention to use, moderated by experience and voluntariness. In addition, the subjective norm may have an impact on the image.

- 1.

Subjective norm

The subjective norm refers to the influence of ‘important’ people or agents on one’s perceptions [

45]. In the hospitality industry, such external referents are competitors, customers, technology vendors, or regulators (e.g., health authorities). For example, a strong focus on competitors can lead to the rapid adoption of innovative technologies perceived as beneficial by others in the market [

46]. Government and health board regulations may influence the choice of the particular technology [

5,

47]. Technology providers also influence the perceived usefulness of the technology as they promote their digital products and solutions and advise clients on the advantages and proposed value of the technology [

38].

- 2.

Image

Recognition associated with technology adoption is another external motivating factor. The aspiration for recognition encourages the adoption of technologies that elevate one’s social status [

45]. For example, aligning with industry leaders and complying with regulations by using innovative digital solutions enhances the image of the hospitality organization and its long-term standing with peers and customers [

48,

49].

- 3.

Experience and voluntariness

Experience gained over time increases user comfort with technology and fosters user trust. While compliance may mandate technology adoption at the initial stages, familiarity with the technology (experience) eventually becomes the driving force as users transition from compliance to comfort [

42]. For example, hotel customers and staff who were initially skeptical about the use of SSTs started to recognize their value in enhancing safety and minimizing health risks: passive compliance was transformed into active participation [

21]. Effective staff support systems may help improve the user experience and accelerate adoption [

36].

2.1.2. TAM2: Cognitive Instrumental Processes

The TAM2 variables related to cognitive instrumental processes are job relevance, output quality, and result demonstrability. They are the antecedents of perceived usefulness.

- 1.

Job relevance and output quality

Job relevance and output quality bring the focus to the workplace. These variables address the fit between technology and a task [

42]. For example, deploying Intellibots (cleaning machines that use laser navigation) helps to utilize the staff shift time more effectively [

50]. However, hotel managers may reject automation in situations where personal interaction is considered important [

22].

- 2.

Result demonstrability

In an organizational context, result demonstrability is about how the new technology enhances job performance. The visible successes of technology adoption reinforce its perceived usefulness and facilitate its broader acceptance within the industry [

14].

2.2. Capability Building and Entrepreneurship in Hospitality

In hospitality research, digital capabilities refer to the organization’s capacity for achieving digital transformation outcomes reliably and effectively [

51] while entrepreneurship underpins innovation and sustainable practices [

52]. Anim-Yeboah and Boateng [

53] differentiate between organizational capacity and capability, noting that while capacity denotes the present level of ability, capability represents a potential for a higher performance achievable under conducive conditions.

Sambamurthy et al. [

38] examine digital transformation as an interplay between capability building and entrepreneurial actions. Their framework captures the dynamics of the processes that lead to innovation and improved organizational performance. Continuous and purposeful digital competence development matching technology advancement allows the organization to identify and select the appropriate digital options [

37]. The new competencies enable agility and innovation; this helps the organization stay competitive by adopting and adapting to new technologies [

42,

51].

Digital leaders guide the organization through the disruptive changes associated with digital transformation [

54,

55]. Acting as social influencers, digital leaders affect the change behavior of other organization members by shaping their attitudes, feelings, and thinking. The role of digital leadership is especially important in the early stages of technology adoption when it is necessary to seize the opportunities presented and to reconfigure the organizational resources [

37].

2.2.1. Capability Building

Adapting to changing market conditions is especially important in crisis situations caused by disruptive events (e.g., a pandemic, a climate change event, hyperinflation, recession, an energy crisis). Tijani et al. [

56] identify a direct correlation between digital capability development and competitive positioning. Continuous employee learning and digital skill development support the ability of the organization to derive value from investing in new digital options [

16].

- 1.

Digital Competence

Digital competence refers to the organizational readiness for digital transformation [

5,

16]. Digital leaders enhance their digital competence by leveraging the skills and knowledge of subject matter experts who exist at all levels of the organizational hierarchy. The organization’s flexibility and ability to respond to change are strengthened by the network of multidisciplinary teams supporting digital transformation [

57,

58,

59]. For example, digitally competent employees and stakeholders increase the hotel organization’s ‘technocratization’ level (i.e., the predisposition to the integration of new technology) and reduce resistance to innovation [

46,

57].

- 2.

Digital Options

To adapt to rapid technological changes, organizations look for opportunities and future digital innovation options such as strategic IT investment and partnerships, or redesigning service offerings to increase their value [

60]. Anticipating and reacting quickly to the opportunities presented by market challenges [

61] requires organizational agility. Both agility and the ability to facilitate spontaneous change are critical for the hotel’s sustained profitability and competitive advantage [

38,

62].

2.2.2. Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial actions integrate organizational capabilities with interpretations of the marketplace to experiment with competitive actions [

38]. Entrepreneurial alertness [

13] helps the organization anticipate changes and seize the right opportunity.

- 1.

Agility, adaptability, and ambidexterity

Agility, adaptability, and ambidexterity determine an organization’s ability to detect and capitalize on innovation opportunities by predicting market trends, to source or reallocate resources effectively, and to adjust its strategies [

16,

54,

57]. Operational agility enables the hotel to transform its operations to benefit from innovation and stay competitive [

63,

64] while organizational adaptability allows it to update the existing capabilities and/or reconfigure tasks and resources [

65].

Even if lacking the capacity to address a disruptive situation, an agile hotel organization can extend its capabilities through partnering, for example, co-opting customers as a source of innovative ideas [

38,

66]. Leadership ambidexterity, or balancing customer service innovation with customer service efficiency, is essential for maintaining the hotel’s organizational agility [

38,

64,

65].

- 2.

Competitive Actions

Competitive moves and countermoves create a cycle of market equilibrium and disequilibrium [

67]. Therefore, achieving success through competitive actions requires both a broad range and a high level of competitive activities [

68]. However, their success depends to a significant degree on the extent to which internal and external stakeholders are familiar with the organization’s objectives and are actively engaged in the competitive actions [

48].

In hospitality, this involves monitoring competitors and building competitive strength [

46]. For example, when a hotel observes a competitor’s actions that yield positive results, it responds by undertaking similar actions to maintain its market standing. The competitive equilibrium is temporarily restored. This is a short-lived state as other hotel organizations engage in further innovations and achieve a superior advantage. This propels the market back into a state of disequilibrium.

- 3.

Entrepreneurial alertness

Entrepreneurial alertness is about developing an ability to sense opportunities for converting uncertainty into profit and new strategic directions [

40,

46]. In hotel organizations, capability building is a prerequisite to competitive actions such as investing in new technology. The success of the investment depend on how quickly the organization makes and implements decisions about competitive actions [

16].

2.3. A Change Management View of Technology Adoption in Hospitality

The agile organization continuously adapts, refines, and integrates its resources to achieve a competitive advantage [

69,

70]. Digital technologies are an organizational resource that acts as both a digital operational tool and as a digital innovation enabler [

71]. The organization ‘learns’ how to effectively use the new digital tools and create business value by developing a capability for managing the transformative process enabled by the technology [

37].

The introduction of new technology in the organization is not an isolated event. Rather, it is an integrative change process that has an impact on the organization’s culture, structure, and stakeholders [

14]. Saghafian et al. [

30] conducted an extensive review of prior research that considered technology adoption as a firm-level process. The authors identified factors that can become barriers to or enablers of technology adoption at each of the three main stages of the adoption process (pre-change, change, and post-change). The authors suggest that organizations can use a change management approach to develop a good understanding of the interactions at the pre-change stage and use the knowledge gained to guide technology adoption at the critical change process stage.

In the context of a hotel organization, a change management approach towards managing the technology adoption adds to the hotel’s resilience [

72] by balancing human and technical aspects. It acknowledges that employee buy-in and customer satisfaction are as important as the functionality of the technology itself [

30]. It is especially important to assess the hotel organization’s initial awareness and readiness for change before the start of the change process [

73].

The eight-step model for organizational change proposed by Kotter [

59] conceptualizes change as a series of leadership activities. It has been widely used in a number of settings [

31], including digital transformation [

74]. The model guides the organization through the change process; it considers preparing for the change and involving employees as important requirements for achieving the envisaged strategic objectives [

75]. The steps of the model are reviewed below.

- 1.

Create a sense of urgency

This step lays the groundwork for the entire transformative process, instilling the intrinsic motivation needed for stakeholders to engage in the change initiatives [

76]. As hospitality organizations are particularly sensitive to shifts in the external environment [

23], recognizing the need for urgent change is critical.

- 2.

Establish a guiding coalition

To guide the change process, a coalition including senior and middle-level managers is established. Once coalition members agree on the value and the benefits of the proposed change, their combined influence will encourage stakeholder collaboration and involvement. This will lead to the emergence of flexible support networks that complement existing organizational hierarchies [

77]. The support networks act as a ‘volunteer army’ whose members ensure the success of the change caused by the adoption of the new technology.

- 3.

Develop a change vision

This step mandates the assembly of a change team, which develops the change vision [

78] and directs and oversees the multiple ongoing change-related projects [

5]. The change vision shows clearly how the anticipated future will differ from the past. In the words of Kotter, the future needs to be ‘imaginable, desirable, feasible, focused, flexible, and communicable’ ([

59], p. 463). Organizations in the hospitality industry have a strong customer orientation; therefore, their change vision is rooted in the understanding of customer requirements and expectations and how these can be met through viable technological innovation [

46].

- 4.

Communicate the change vision

Participation and understanding of the change vision are important for the successful implementation of the transformation and its ultimate profitability [

42]. Therefore, the change vision message needs to resonate intellectually and connect emotionally, building trust and motivating employee participation [

76]. For example, Rubel et al. [

79] found that the effectiveness of the technology adoption process was enhanced by developing employee knowledge, skills, and abilities that were directly related to the organizational goal for the change. In addition to improving organizational performance, this approach strengthened employee loyalty.

- 5.

Remove barriers and empower

According to Kotter [

59], barriers within an organization can be structural and procedural. In the hospitality sector, employee and manager resistance to change is a structural barrier [

80] that can become an impediment to achieving the organizational goals and vision. Similarly, the lack of an adequate transition process that empowers employees to bring in innovation is a procedural barrier that can also derail the change effort [

81].

- 6.

Generate short-term wins

Short-term wins encourage the development of an organizational culture that accepts change and encourage stakeholders to sustain the change initiative into the future [

59]. Change leaders will be able to report quickly and frequently on positive outcomes by carefully planning change implementation and structuring the realization of the benefits. For example, the hotel organization in [

50] adopted some artificial intelligence (AI) technology that was well-received by customers. The positive customer feedback helped sustain the momentum and the hotel was able to optimize other aspects of the business through additional technology integrations [

50].

- 7.

Consolidate improvements

To build on the success already achieved and introduce more profound changes [

59], the organization consolidates the innovation gains. The aim of this step is to reinforce the sustainability of the organization’s vision and build a competitive and adaptable organization [

65]. Strategies such as engaging more people in the change initiatives and encouraging more active involvement from senior managers help counteract potential resistance and solidify advancements [

76].

- 8.

Anchor change

Kotter’s model includes an important last step: ensuring that the changes are fully integrated within the organization’ s operational fabric and embedded in the organizational culture [

59]. Continuous dissemination of clear and transparent information regarding the results of the change and communicating the tangible outcomes ensures that the innovative modifications are institutionalized. This provides a foundation for further incremental changes. For example, the hoteliers in [

42] continued to monitor customer feedback and adjust operations after SSTs were deployed. The incremental changes resulting from the adjustments were less disruptive than the initial change. As Busulwa et al. [

54] point out, the anchoring of the new technological advancements within the organizational culture strengthens the resilience and the adaptability of hotel organization.

3. The DEAC Framework for Managing Technology Adoption in Hospitality

Intersecting the theories and model discussed above, the DEAC framework proposes a conceptual representation of the processes associated with technology adoption in the hotel organization. It views the interactions between the organization and the technology as a managed change process in which the adoption of new technology is underpinned by the organizational culture, capability, and entrepreneurship. The framework places an emphasis on combining entrepreneurial foresight with the agility to implement changes effectively.

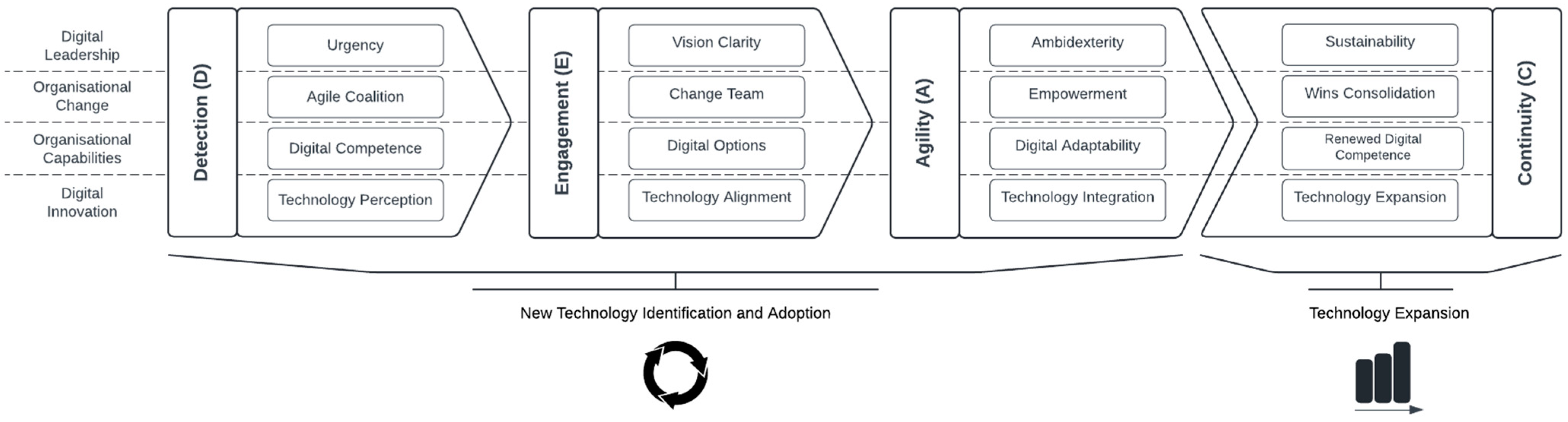

As shown in

Figure 1, the objective of the first three stages (detection–engagement–agility) is to identify, select, and adopt the technology that is best-aligned with the strategic organizational goals. The last stage (continuity) reflects the continued use of the innovative technology after its initial adoption. At each stage, the specific activities relate to organizational leadership, change management, and capability development, and digital innovation through technology adoption.

3.1. Stage D: Detection

Stage D (

Figure 2) is the initiation stage. The hotel organization recognizes the necessity of urgent action as current strategies are no longer adequate [

7,

23]. A sense of urgency is created [

59]. The organization scans the market to gauge technological trends, competitor activities, and customer reactions [

45] and identify opportunities for organizational change.

An agile digital leadership style is adopted to ensure that managerial decisions about technology adoption are aligned with budgetary constraints [

5,

16]. Agile coalitions are formed to promote stakeholder engagement and quick decision-making [

59]. Agile coalitions collaborate with subject-matter experts. The experts provide a range of diverse perspectives to assist leadership in the identification of strategic and operational deficiencies and the evaluation of digital alternatives for competitive actions. With agile coalitions in place, the organization proactively seeks technologies that can enhance its capabilities and provide it a competitive edge

An immediate internal examination is triggered to evaluate critically current capabilities [

38]. The hotel organization assesses its digital competency from IT infrastructure to IT management practices, including employee readiness for technology innovation [

5,

16]. Employee perceptions about the usefulness and ease of use of the new technology contribute to forming perceptions about its value [

6,

9,

63].

To enhance the ability to seize opportunities, feedback from external stakeholders (suppliers, partners, competitors) is also sought [

38,

53]. For example, suppliers influence the perceived value of the technologies considered for adoption by providing a subjective norm reference (i.e., information about the dominant technologies in the current market) while partners and competitors provide an image reference (i.e., information about the most preferred technologies in the market) [

45].

Overall, the activities at this stage are directed towards discerning technologies that mitigate the identified capability shortfall and facilitate organizational progression and competitiveness. At the end of this stage, the hotel management team should have developed an informed view of the organization’s technological needs, customer preferences, stakeholder expectations, and opportunities to innovate.

3.2. Stage E: Engagement

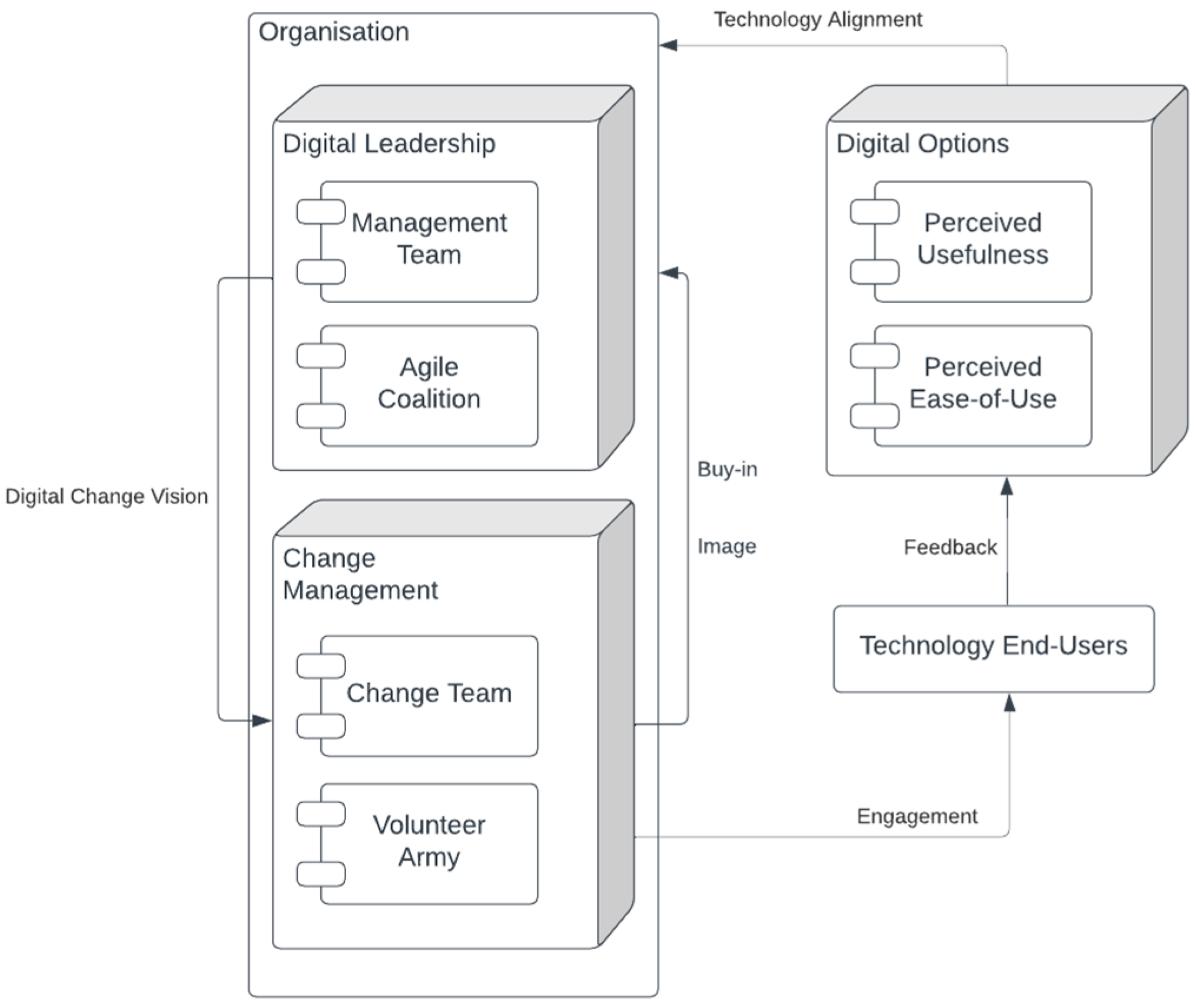

The engagement stage (

Figure 3) is about strategic planning and developing and communicating the digital change vision [

59]. A compelling and clear change vision evokes a sense of shared purpose and direction and fosters a collaborative atmosphere that engages stakeholders. In the hospitality sector, the digital change vision must be customer-centric, competitor-aware, and technology-oriented [

41]. The careful consideration of the digital options [

38] guided by the digital change vision ensures that the new technology aligns with the hotel’s strategic objectives and the innovation is technologically feasible.

To integrate new knowledge and reconfigure its operations and resources, the hotel organization continues to develop its operational agility embodied by the agile coalition [

65]. A change team is formed; it communicates the change vision to engage stakeholders and foster commitment [

59,

77,

78]. The change team and the volunteers act as a core group of change advocates within the organization. They promote the proposed change to stakeholders as a means of elevating the hotel organization’s image and industry standing [

7,

48], which helps counteract resistance to change. Showing how the usefulness and ease of use of the new technology support operational excellence [

45] helps secure stakeholder buy-in.

A high-level managerial engagement in continual dialogue and collaboration with stakeholders is particularly important at this stage [

78]. The process allows for an iterative adjustment of technology adoption plans and lays the groundwork for an informed and agile technology adoption process.

3.3. Stage A: Agility

After the first two stages, the hotel’s management and the change team supported by the members of the agile coalition and the volunteer army are ready to apply an agile approach to digital innovation. At stage A, the organization focuses on the execution and monitoring of the technology adoption plan. This involves the proactive adjustment of organizational resources to facilitate efficient technology integration and optimization (

Figure 4). Digital leadership ambidexterity [

13] helps create a responsive and innovative technological environment that is in alignment with the hotel’s strategic business goals.

Structural and procedural obstacles can stifle the momentum of change [

59]. To remove the barriers to innovation, the organization continues the empowerment process by promoting a culture in which employees accept change and innovation. Meanwhile, the change team monitors and proactively addresses emerging issues related to technology integration and resistance to change and facilitates access to training and upskilling programs.

The relevance of the new technology to employees’ jobs and customer-related tasks and the quality of the generated task outputs positively influence the acceptance of technology integration [

45]. Quick wins provide tangible evidence of how the new technology aligns with the organization’s strategic objectives and improves service quality. These short-term victories serve as success indicators [

78] and help maintain the forward momentum of the change initiative. Demonstrating the efficacy of new technologies through quick wins [

59] helps obtain stakeholder support [

46].

Overall, Stage A is a highly interactive process of garnering end-user feedback about the implementation of the change and responding to it. The agile hotel organization develops a culture that encourages continuous learning, adaptability, and openness to iterative feedback [

36,

60]. The organization’s resources are reconfigured and optimized to support job-relevant technology integration and to enhance output quality.

3.4. Stage C: Continuity

Once the new technology is successfully integrated into the hotel’s business processes, the organization transitions to the continuity stage (

Figure 5). This ensures that the new technology is a permanent enhancement and not just a temporary measure. The focus of the digital leadership is on consolidating the wins [

59] and leveraging the success of the initial changes to achieve sustained growth and improvement. Hotel employees continue to be provided with opportunities to acquire and develop their skills and knowledge. The continuous improvement in the organization’s digital competence positively influences information seeking for complementary technology and further technology expansion [

79].

The organic growth from initial technology deployment to expansive technological integration is facilitated by the culture of continuous service innovation. End-users (customers, hotel staff) gradually become more familiar with the new digital offerings and start recognizing their intrinsic value [

13,

45]. The feedback loop captures end-user satisfaction and engagement and provides insights into evolving user requirements and expectations.

Changes are not just instituted but institutionalized as the benefits of the technological expansion are realized. However, the agile hotel organization strives to maintain a balance between institutionalization and innovation. It anchors the adopted technology in the organizational processes to ensure sustainability and resilience and also to build a momentum for more extensive change. Resistance to change can still be significant, but so is the potential for sustainable change, as the very notion of change becomes embedded in the organizational culture [

36].

3.5. Case Studies

The case studies below provide practical examples of activities relevant to the stages of DEAC. The hotels settings are a luxury resort (Marina Bay Sands) and an affordable hotel chain (Puro Hotels Wroclaw).

3.5.1. Marina Bay Sands

During the period of 2016–2021, the Singapore-based luxury resort Marina Bay Sands effectively and sustainably implemented technologies that have contributed to it achieving its strategic objectives. When examining the case through the lens of DEAC, it can be seen that the hotel moved quickly through the initial DEAC stages (detection and engagement) to evaluate the digital landscape for new strategic partnerships and opportunities [

50,

82,

83]. The organization applied an agile approach to the adoption and effective use of automation and high-tech applications in targeted areas of hotel operations. The Intellibot cleaning machines allowed for time saving and more efficient cleaning staff deployment while the Superlizzy waste compactors streamlined waste management and supported the hotel’s sustainability initiatives.

The highly technocratic organizational culture of Marina Bay Sands contributed to it consistent success in integrating technology-supported operational strategies (consistent with the activities in the third DEAC stage, agility). Short-term wins acted as milestones in the process, reinforcing the ethos of change. The demonstrated and visible success of the new tools and systems reinforced their perceived value and relevance. Technological innovation measurably improved front-stage operations, as evidenced by a progressive rise in the hotel’s net promoter score.

Marina Bay Sands sustained its momentum for change and moved on to optimizing other aspects of the business (corresponding to DEAC’s continuity stage). For example, integrating AI into the interactive voice response system allowed contact center staff to speed up caller identification; about 70 percent of the calls were successfully triaged, improving the overall service experience.

3.5.2. Puro Hotel Wroclaw

Puro Hotel Wroclaw belongs to the Puro Hotels hotel chain in Poland. It was established during the period of 2010–2012. Its strategic objective was to achieve a sharp reduction in service time by implementing SSTs while maintaining an attractive service quality–price ratio [

66]. In this case, the chain investors acted as change leaders. Consistent with the detection stage in DEAC, hotel manager entrepreneurship was encouraged by the chain investors to seek solutions that followed global trends.

External stakeholders were significantly engaged in the identification of the potential digital solutions (as at the second stage of DEAC). High-tech companies operating in Poland such as Samsung Electronics Poland, Procom Systems, and Software Mind provided technical consultancy services while the targeted customer base (young travelers) was contacted via online media and invited to articulate its requirements and expectations. Thus, the leadership team was able to identify a set of high-level technology selection criteria that were aligned with the organization’s strategic objective and with customer needs, and ensured the sustainability of the integration: (i) it was safe for both hotel guests and employees; (ii) it integrated with the existing BAS/MS (Building Automation Systems/Building Management Systems); and (iii) it was highly functional and efficient for both staff and customers.

At the implementation stage that followed, the integration of the smart solutions was supported by Puro’s highly skilled staff (consistent with the agile stage in DEAC). Hotel employees developed a clear vision of the positive impact of the adopted technology on task productivity. The adopted smart technology brought a measurable competitive advantage to the enterprise, and Puro Hotels developed a public image as an affordable yet high-value customer service provider, and a leader in digital innovation. The hotel achievements were recognized with the receipt of multiple prestigious awards.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The recent global pandemic challenged the financial stability of the hotel industry and necessitated a quick response [

1,

7,

84]. Consequently, the sector witnessed a surge in new technology integrations that were often rushed and not always successful. This was due in part to the lack of strategic planning [

11] and also to manager resistance to digital innovation, especially in high-touchpoint customer service areas [

22,

81]. Despite the hesitation to move beyond traditional service delivery models even in the case of a global disruption [

80], hotel organizations do share a collective understanding of the need for continuous technological improvement as a means of remaining competitive [

81].

The research question of this study was formulated with the intent to synergize technological, entrepreneurial, and managerial dynamics to foster successful digital technology adoption. To address the research question, this study first developed a theoretical background that included TAM2 [

45] as a model for representing technological dynamics, Sambamurthy et al.’s [

38] framework for capability building and entrepreneurship to represent entrepreneurial dynamics, and Kotter’s [

59] change management model to represent managerial dynamics. The conceptual framework (DEAC) proposed in

Section 3 draws on the intersection of these three theoretical models, as shown in

Table 1. It considers technology adoption as a change management process that connects the building of digital capabilities within the organization [

38] to the strategic alignment between the new technology and the hotel organization’s business goals [

55,

59].

As also illustrated by the two case studies (Marina Bay Sands and Puro Hotels), the structured process begins with assessing digital readiness and detecting technological opportunities, where the organization identifies and evaluates the digital technologies that are operationally relevant and address market challenges.

The focus then shifts to engagement: actively involving internal and external stakeholders. Engagement is critical for gaining a buy-in and ensuring the changes are well-received and integrated into the organization’s daily operations. For example, the Puro Hotels leadership derived technology selection criteria through stakeholder engagement.

The agility stage emphasizes interaction, a rapid response and implementation, and flexibility. Being agile means adapting the organization quickly to new technologies, customer preferences, and market trends. Both case studies show how the ability to demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the new technology in practical terms and the strong digital competence of the hotel employees had a positive impact on the pace of the adoption process.

The continuity stage is about solidifying the gains achieved from the digital initiatives and building upon them to establish a sustainable and future-proof business model. Consistent with Grant’s [

85] research, the strategic renovation of organizational digital competence gives birth to new skills, knowledge, and organizational structures. The organization is able to keep up with current digital trends and anticipate and prepare for future developments. For example, Marina Bay Sands proceeded to automate its background operations. Puro Hotels prepared for future innovation by mandating the use of an enabling platform.

Towards the end of the last stage, the organization has mastered the use of the specific technology and has developed an organizational culture that values continuous learning, innovation, and resilience. The DEAC cycle can recommence, guiding the organization through another phase of digital transformation. This recursive aspect of the proposed framework is one of its most significant features. It recognizes that growth and adaptation are continuous processes in the fast-paced, ever-changing world of hospitality. Organizations can maintain relevance and competitiveness by cyclically moving through the detection, engagement, agility, and continuity stages. The cyclical approach ensures they are always poised to seize new opportunities, tackle emerging market challenges, and foster ongoing innovation and development.

4.1. Comparison with Prior Work

Digital innovation and, in particular, technology adoption are integral parts of the digital transformation process [

30]. Therefore, a comparison can be drawn between this study and the proposed DEAC framework and studies that consider amalgamating or combining change management and digital transformation models (DTMs).

The often-cited earlier work by Bellantuono et al. [

39] published in 2021 analyzes DTMs through the lens of change management to identify the degree to which extant DTMs consider a change management perspective. The authors identify a number of omissions. For example, most of the reviewed DTMs do not include the establishment of a team specifically dedicated to and tasked with the process of digital transformation. As discussed, DEAC places a strong emphasis on setting up and empowering a change management team (stage E), supported by agile coalitions and a volunteer army. Second, most DTMs do not explicitly include a change monitoring activity. DEAC provides a place for this in stage C, where monitoring is part of the iterative agile implementation process. Third, most DTMs do not make provisions for managing resistance to change. DEAC addresses this extensively by using technology acceptance antecedents (result demonstrability, output quality, and job relevance) to counter resistance to change in stages A and C. Finally, most DTMs do not include an activity that consolidates change. In DEAC, institutionalizing and consolidating change are part of the activities in stage D.

A study published in 2023 by Pulido et al. [

73] also compared change management models and DTMs based on a review of the literature. The analysis established that the two model categories had commonalities (‘intersections’) in four areas. The authors labeled the intersections ‘Getting ready’, ‘Strategy’, ‘Enable change’ and ‘Scale up and deliver value’. The DEAC framework also applies an intersecting approach. A comparison shows that the first and second stages in DEAC (D and E) are somewhat similar to ‘Strategy’ and ‘Enable change’. However, DEAC posits that that delivering value is a process outcome that is enabled by the strategic alignment between technology and organizational goals and the agile implementation of the innovation. The value delivery process is not confined to one stage. Rather, it runs across the stages and is visibly manifested, and stages D and C ‘Scaling up’ are part of the last DEAC stage.

Based on the analysis of their findings, Pulido et al. [

73] recommended the creation of an integrated framework that maintains a strong focus on motivating and empowering people (which is a change management paradigm) while also addressing the need to assess the viability of the change options and to develop adequate digital capabilities. The DEAC framework is consistent with these recommendations. First, it places people at the center of the adoption process in each of the stages. Second, DEAC emphasizes the need for technology assessment (stage E) and skill development across all stages.

A recent study by Fischer et al. published in 2024 [

31] also offers an extensive systematic literature review. Rather than compare or intersect models, the authors identify a wide range of change management activities that need to be part of the digital transformation. They propose a framework for change management in digital transformation that groups the activities in four interrelated stages: ‘Frozen, ‘Unfreezing’, ‘Moving’, and ‘Freezing’.

The stages of the DEAC framework can be mapped onto the stages of Fischer et al.’s [

31] framework. However, in [

31] as well as in the two other studies reviewed above, technology is considered predominantly as an agent of change (i.e., as a driver or enabler) in digital transformation, with little focus on the process of technology adoption. Technology cannot successfully fulfil its role as a digital transformation driver/enabler unless it is successfully adopted. The proposed DEAC framework specifically focuses on how to manage the adoption process to achieve successful adoption, including the disruption caused by technology innovation. In particular, DEAC builds on TAM2 to mitigate the impact of technology adoption barriers and amplify the impact of the positive factors.

4.2. Study Contributions

This research demonstrates the benefits of linking technology acceptance and adoption theories and of entrepreneurship and change management models in the context of the hospitality industry. The DEAC framework adds to the academic discourse on technology adoption by connecting it to the challenge of managing change within organizations and showing how the integration of the processes of change management and digital capability building can lead to successful digital innovation. The four stages of the framework represent the process of technology adoption from initiation to institutionalization to new challenges. This process fosters the development of new organizational competencies and promotes organizational resilience and strategic sustainability.

The novelty of the DEAC framework lies in connecting theoretical constructs with the tangible needs of hotel organizations. The synthesis of Kotter’s change management model [

59] with capability building and entrepreneurial actions [

38], along with the TAM2 pre-implementation factors [

45], provides a research framework for the empirical exploration of digital innovation in hospitality research. The framework can be adapted to other contexts such as the entertainment industry or traditional retail companies. Both sectors face challenges from strong online competition [

86,

87].

The DEAC framework can also be used as a practical guide; a tentative list of high-level activities at each of the stages is provided in

Appendix A,

Table A1. First, the framework emphasizes cultivating a competitive advantage through agile actions; this is particularly salient as it allows for a fast response to changing customer needs. Therefore, hoteliers should systematically evaluate digital adoption potential and agility factors through an integrative approach before engaging in entrepreneurial activities. Second, the framework underscores the importance of facilitating organizational culture shifts and encourages an approach to technology adoption that is harmonious with human factors in addition to being a strategic endeavor and operational necessity. To achieve this, managers should critically assess the perceptions of technology end-users and manage resistance to change through inclusion and empowerment.

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

This study comes with several important limitations. First, the DEAC framework draws on three particular theoretical models. Therefore, the ability of the framework to capture the dynamics of the technology adoption process is limited to the variables and constructs of the selected models. Second, the identified connections are underpinned solely by the theoretical structures reviewed and lack an empirical validation. Third, the framework is a qualitative one and does not include instruments for quantitatively measuring or evaluating the success of the activities at the different stages. Fourth, the framework is rather generic and does not differentiate between different hotel types found in the hospitality sector (e.g., large hotel vs. small hotels, budget hotels vs. luxury resorts).

Further research can overcome some of these limitations. Directions for further research include developing research models and evaluation metrics for empirical studies to test and validate the framework. Case study research, in particular, will bring in an industry perspective and suggest ways of refining or readjusting the framework to take into account the specific characteristics of different hotel types.

Furthermore, the theoretical foundation of the framework may be expanded to incorporate new variables. For example, ‘user involvement’ in the TAMUI model proposed in [

88] and ‘performance expectancy’ and ‘facilitating conditions’ in the UTAUT model [

89] can be used to reflect user change behavior more precisely across the four stages of the framework. The dynamic capability ‘organization resilience’ [

90] can be incorporated explicitly at the initial stage as a change driver, especially at times of crisis. It would also be of interest to explore how the organizations’ leadership engages in digital learning (or employs digital natives) to inform decisions about digital innovation, and how the level of technocratization affects the outcome of opportunity scanning for digital options. Another avenue for research is exploring the applicability of the framework to other industry sectors that are characterized by disruptive market forces and rapid technology expansion.

4.4. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel theoretical intersection of concepts representing technology adoption and organizational capability building. It develops and conceptualizes a change management perspective on digital innovation in hotel organizations. The proposed DEAC framework aligns the identification, selection, and adoption of new technology with the strategic goals of the organizations in a sequence of competitive actions supported by the organization’s agility, digital capabilities, and change management strategies.

The specific activities at the different stages of this process framework relate to developing a vision for sustainable change, engaging internal and external stockholders, empowering technology end-users, and promoting an organizational culture that is open to change and innovation. The ultimate objective of the process is to achieve continued use of the adopted technology. This enables the hotel organization to realize the business value of the innovation and to prepare for a new cycle of technology integration. The framework provides a structured and actionable blueprint for achieving successful and sustainable migration to newer technologies or practices in the context of the hospitality sector.