1. Introduction

2015 will be remembered as the year of the sale of one of the most historic symbols of Italian industry to new foreign owners. Pirelli, founded in Milan in 1872, passed its control to the state-owned giant China National Chemical Corporation (ChemChina). In a deal worth over seven billion euros, the Chinese chemical giant has acquired the world’s fifth-largest producer of tires. The transaction led to the delisting of Pirelli’s shares from the Milan Stock Exchange, now 100% owned by the holding company labeled with the evocative name of Marco Polo Industrial Holding SpA, in which ChemChina’s subsidiary, China National Tire and Rubber Co., Ltd., and a minority shareholding by the financial company Camfin.

The Chinese takeover of one of the first and longest-lived Italian multinationals and two very popular companies has drawn attention to Chinese takeovers of Italian companies in recent years. In 2014, Italy was, in fact, the second-largest market for Chinese acquisitions in Europe and the fifth-largest in the world [

1]. The number of Chinese activists is indeed remarkable and growing. In 2014, China owned stakes in 322 Italian companies that employed 17,788 people and had a combined turnover of €8424 million [

2]. One just needed to read the headlines of the major Italian newspapers to perceive the alarm raised by an alleged threat to the country’s economic and industrial heritage [

3,

4,

5]. However, Chinese acquisitions in Italy follow a well-defined strategy [

6,

7]. Chinese multinationals have invested in valuable assets of our economy—from Mediobanca to IntesaSanPaolo, from Terna to Eni and Enel—but only in rare cases have they concluded a real acquisition of an Italian company, understood as the attainment of a controlling stake. The most emblematic cases are precisely those already mentioned by Pirelli and the more visible ones of football clubs. However, Chinese appetites are not immune to indigestible effects: a study on the failed Chinese takeover of the historic motorbike brand Benelli [

8] highlighted the difficulties caused by different organizational cultures in conducting a successful corporate take-over.

Leaving aside the news coverage debate that inevitably turns the spotlight on the most sensational operations, it perhaps makes more sense to discuss the ongoing trend of the concentration of economic activities on a global level and the redistribution of technologies, a process in which Italian companies are mainly involved because of this passive internationalization. What deserves the commentators’ attention is the close link that is also emerging in Italy between internationalization and materialization, once the phenomenon of family ‘pocket multinationals’ has remained on the sidelines. The internationalization, albeit passive, of companies acquired from abroad thus determines the shift towards a greater presence of managers outside the ownership. A change in management obviously goes hand in hand with a change in ownership of the company and thus leads to transformations not only in ownership but also in control. For this reason, it is useful to reflect on which and how many Italian companies have seen a real change in corporate control following a foreign acquisition for a share of more than 50% of the capital, and thus not limited to a simple entry in the capital.

The entry of foreign capital is certainly a good sign for any economy, even in the form of share acquisitions. The transfer of control of a company, on the other hand, is another matter. This matter has so far remained poorly researched. This paper aims to put under scrutiny the changes in corporate structure involving the acquisition of the entire company or controlling stake by foreign groups in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) completed between 2010 and 2015.

However, the common knowledge is that the transfer of corporate control to a foreign owner is detrimental to the national economy. Research on M&As is as abundant in studies as in cognitive biases that limit the field [

9]. This article tries to shed light on the trend of foreign acquisition during the later wave of M&As before the global pandemic of COVID-19 [

10] and traces the transfer of corporate control to foreigners. In doing so, this research adopts the target’s perspective, while most studies look at the acquirers’ performance. More in detail, this paper explores the shifts in corporate control across borders, i.e., that acquisition that involved the transfer of at least 50% of the shares of a company to a foreign owner. The reason for this selection is to consider only the change in the ownership structure and avoid investments in the minority of the shares. The change in ownership consists of a deliberate strategy to take control of the company, while the acquisition of shares may consist of a simple investment diversification strategy.

The paper unfolds as follows. The next section reports on the background of the research;

Section 3 returns to the context and the strategy of the research.

Section 4 draws a map of the foreign takeovers to understand strategies and trends; the next section builds on the evidence to provide results that contribute to the debate. Lastly, the discussion and conclusion summarize the results and derive prescriptions.

2. Theoretical Background

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) are of key relevance for business strategy and organization [

11]. Scholars have attempted to evaluate the performance of M&A operations by looking at the changes in the results, for example, using accounting data from financial statements [

12].

This practice has advantages and disadvantages. For instance, it implies objective data; financial accounts are indeed more reliable than market valuations that reflect the sentiments and perceptions of investors and similarly reflect more long-term changes in performance [

13,

14]. Research considers performance in terms of productivity and profitability [

15,

16,

17] and implies multiple variables [

18]; among others, sales or revenues [

19,

20,

21]; net sales/assets ratio [

22]; net income and EBITDA and company cash flow (Powell and Stark, 2005) [

23]; return on investments (ROI) [

24], return on equity (ROE) [

25], and return on asset (ROA) [

26].

There are two main shortcomings to this method of evaluation. First, it usually assumes the viewpoint of the acquirers [

22,

27,

28], and second, it hardly distinguishes the strategies of M&A operations from the western of emerging markets [

29]. For the first, studies found that the target companies share the fear of reducing employment by witnessing the transfer of jobs and assets abroad; however, evidence suggests that foreign acquisitions do not lead to the loss of jobs or relocation of production abroad [e.g., in Italy, 29]. Nevertheless, this area of research is relevant to its social impact and is highly underdeveloped in terms of studies on economic performance.

The second prominent exception is the work of Buckley and colleagues [

12,

30], who used net income and sales to explore the impact of acquirers from emerging markets on the performance of companies. Despite this remarkable contribution, understudied areas remain. For instance, acquirers from emerging markets usually target companies in Europe to obtain intangible assets that create synergies aiming at long-term efficiency and technology adoption more than gains in profitability [

28,

31,

32]. Many of those acquisitions concern small-medium enterprises (SMEs) that are mostly unlisted; therefore, the analysis of their accounting returns cannot rely on their financial statements [

33].

However, despite the relevance of foreign acquisitions and the recurrence of M&A waves [

34,

35,

36], they often fail, particularly when involving companies from different countries in cross-border mergers [

37]. The difficulty in concluding a profitable operation of M&As is greater for emerging multinational enterprises [

38,

39,

40,

41] because of their limited international experience and the divergences in behavior and culture between Western companies and those from emerging markets [

42,

43,

44]. Nevertheless, M&As remain the preferred strategy for direct investment of emerging market multinationals [

32,

45,

46,

47], mainly to access a greater pool of knowledge and skills [

48].

Several studies found that foreign takeovers diminished the value of the target companies, up to the destruction of shareholder value [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Exceptions exist and cannot be underestimated. There is evidence of the positive impact of foreign ownership on target companies [

53,

54]. Scholars found firm-specific advantages of foreign acquirers in cross-border deals that can positively influence the performance of target companies [

55,

56,

57], i.e., technological expertise, networking, and access to capital [

58,

59,

60]. Others suggested that foreigners conclude better deals for the targets than domestic acquirers [

59,

61,

62] in terms of gains in performance [

63]. Overall productivity [

64,

65] and risk-reduction against market turmoil [

66,

67].

One reason for the advantage of foreign takeover over domestic may be that foreigners tend to be more controlled than domestic firms and, therefore, must provide higher benefits to conclude the deal [

68,

69]. Overall, questions remain unanswered concerning the strategies, dynamics, size, and impacts of foreign takeovers of companies in Europe. This paper explores the cross-border M&As targeting at least 50% of the ownership of companies in Italy during the seventh wave of mergers (2010–2015) to shed light on the many understudied areas and contrast misconceptions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach and Data

This paper assumes an exploratory strategy and combines both standard methods of evaluation that rely on financial accounting data and the analysis of acquisitions. The paper identified operations of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) through Zephyr (Bureau van Dijk’s database [

70]) and considered only acquisitions of a controlling interest (>50% of shares) for a total of 446 operations over the period 2005–2015. Second, the research controlled for economic and financial indicators of the acquired companies for the period 2005–2022, which includes a lag of at least eight years after the acquisition. Note this extended period includes the COVID-19 pandemic with its economic bump and following hypes and downturns. Given the nature of this study, which at the same time follows a traditional perspective of M&As valuation based on financial accounts and tries to emphasize the strategic and industrial dynamics underlying the last wave of M&As, the approach remains largely descriptive, as this research argues more on the macro trends than on measuring effects on financial variables at a micro level. For those reasons, the research avoids the test of hypotheses but explores a more research question in search of novel evidence. This research approach is more prone to pose questions that start with “how” and “why” than “what is” or “how much”. This article aims to offer a rational perspective on the controversial topic of foreign acquisition; therefore, the research question is:

how do Italian companies react and evolve after foreign acquisitions?This article investigates a certain and specific subset of completed acquisitions, those that have resulted in a change in corporate control. The acquisition direction of interest to this research is that of foreign acquisitions targeting Italian firms, whose ownership and control transfer to foreign companies or groups. The transfer of ownership and control is determined when more than 50% of the shares in the capital are acquired.

The information and data were collected and selected from the databases made available by the business information provider Bureau van Dijk, and in detail referred to the Aida database, with reference to news of Italian firms; Orbis with regard to foreign firms; and Zephyr for details on M&A transactions.

The time period covered is 2010 to 2015. As demonstrated in the opening of this paper, this is the period of return to acquisition activity to pre-crisis levels. Of further interest to the present research is the distinguishing feature of this seventh historical wave of acquisitions, namely the increased number of foreign acquisitions over the period. The transactions in our sample were all consolidated by 31 December 2015. These time limits include 446 cases useful for our investigation.

The data made available allow us to assess, in addition to the countries of origin of the acquiring companies, the sectors of reference, for which we use the Nace (Nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne) codes and the related Ateco conversion performed by the Italian National Bureau of Statistics (ISTAT). Other data consider the share of capital changed hands, the corporate form, the number of employees, and the value of the operation.

3.2. Research Context: The Last Wave of M&As

The international crisis in 2007–2008 caused a slump in global M&A transactions. The first year of the crisis, 2007, set an all-time record for M&A deals (

$3.8 trillion, [

71]) and concluded the sixth wave of takeovers recorded in the last 125 years [

72]. Due to the global economic downturn, deals dropped by a third in terms of value, only to return in 2015 to levels in line with pre-2008 levels.

The syncope of the world economy has only momentarily suspended a process of strong corporate concentration and initiated a new wave of acquisitions. This seventh wave of deals is distinguished from the previous ones by an accentuated growth in international deals, the so-called cross-border acquisitions, which in 2015 accounted for 43% of the worldwide value of acquisitions undertaken. The latter figure is even more significant in Europe, an area where cross-border acquisition activity accounts for 80% of the total value [

71], and establishes the central role of acquisitions as a way of accessing foreign markets.

Within this scenario, Italy is positioned below its potential as one of the most industrialized countries in the world. Foreign direct investment (FDI) to Italy did not reach 20% of GDP before 2015 [

73]. Italy was fifth in Europe in terms of value and number of transactions (6% and 5% of the European total, respectively), far behind France (20% and 13%) and the United Kingdom (28% and 22%), which led the ranking, far behind Germany (15% and 11%) and slightly after Spain (7% for both values [

71]).

3.3. The Italian Market for Corporate Takeover

Italian M&A activity is going through a very peculiar trend. On the one hand, the number of total transactions involving Italian companies—be they domestic transactions, takeovers of foreign companies, or acquisitions of Italian companies by foreign companies—has exceeded pre-crisis values: 543 transactions in 2014 compared to 459 in 2007. On the other hand, the total value of transactions is far from the level of 148 billion Euro reached in 2007 (the historical record of transactions dates back to 1990). In 2014, the value corresponded to just over a third of the pre-crisis figure, EUR 50 billion (elaboration on Bureau van Dijk data).

The change in the trend in recent years is measured by the increase in transnational transactions targeting Italian companies. Foreign acquisitions in Italy set a new record in 2015 worth more than 32 billion euros. Over a period of about ten years, acquisition transactions between Italian firms (“domestic” transactions) have gone from about 2/3 in 2005 to less than half of the total in 2014, while international transactions reversed at the turn of the 2008 crisis [

71]. Since 2009, transactions of Italian companies making acquisitions abroad (“out”) have been lower in proportion to transactions involving the foreign acquisition of Italian businesses (“in”), the latter counting for more than a third of total M&A activity in the last two years (see

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Furthermore, the countervalue of transactions is clearly in favor of foreign acquisitions in Italy, more than half of the total since 2014 (see

Table 2).

3.4. Foreign Acquisitions in Italy

Many reasons may exist to justify the increase in foreign acquisitions in Italy. Renewed confidence in the country, the attractiveness of some valuable assets, and the large availability of liquidity in the international market.

Foreign acquisitions made in Italy account for more than half of the cases of corporations from European Union member states (

Table 3). The remaining half is almost equally divided between North America and all remaining countries. The United States is the top country for the number of transactions with Italy, followed by Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and China ([

71] p. 72).

A contemporary study [

74] (Prometeia 2015) assesses over a period of more than ten years the entry of foreign capital, mainly in the most competitive Italian companies, in terms of balance sheet and technological assets. Thus, it is not companies going through a business crisis that attract foreign buyers but those that are well established and often already under the control of managers external to the ownership. The same survey finds that over the period 1999–2013, firms subject to foreign acquisition grew with a differential of 3.5% in productivity and 1.5% in employment. It follows those foreign acquisitions prior to the last crisis that brought the availability of capital, which Italian firms are chronically in demand to support the development process by maintaining or accelerating its technological innovation dynamics.

4. Analysis

4.1. The Acquisition of Control

There were 446 transactions involving the transfer of capital of Italian companies to such an extent that it also constituted a transformation of control of the acquired company to the new foreign ownership in the period between the beginning of 2010 and the end of 2015. All of the transactions surveyed were completed and finally consolidated by 31 December 2015 and sanctioned the achievement of an absolute majority of capital by a foreign company. From 28 ownership changes in 2010, transactions more than doubled in the second half of 2014 alone (see

Figure 2), after which they fell back to levels comparable to the early years of the period under review. The two years between the last half of 2013 and the first half of 2015 saw the largest number of acquisitions of Italian firms: 219 transactions, counting just under half of the six years under consideration.

Table 4 shows the country distribution of acquiring companies. The top five countries by origin of acquiring companies are the United States and four Western European countries, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland. These five countries alone account for more than 60% of the control acquisitions made in Italy. The top three countries in this ranking, the United States, France, and Germany, alone exceed 47% of the total. The U.S. accounts for 24% of the total despite not benefiting from membership in the European single market. The possibility of access to the huge European market through an Italian company would be a strong incentive for non-EU companies. This does not appear to be true, however, for firms from the BRICS countries. These count only 28 acquisitions, less than 6% of the total, a number only slightly higher than operations from neighboring but small Switzerland. Noteworthy among the other countries are the 13 Japanese acquisitions, nearly half the number from Brazil, Russia, India, and China (including Hong Kong), which combined with those from the next two countries in terms of the number of deals, The Netherlands and Spain, equalize those from the BRICS. Of considerable interest is the number of transactions from Luxembourg, as many as 17. Luxembourg companies very often have their operational headquarters in a different country, so they should be considered carefully when assessing the origin of buyers. For the purpose of the present research, the headquarters was identified on the company’s institutional site, and that location was considered the country of origin of the acquiring company.

Almost all of the cases of acquisition of control under our investigation occurred in the absence of a previous equity stake. As shown in

Table 2, only in 10 cases did the acquiring companies have a shareholding, which they later expanded until they reached a majority (

Table 2). Of the 446 Italian companies whose control was transferred abroad, as many as 436 were acquired in a single transaction, thus not consolidating previous capital-holding relationships (

Table 5).

Table 6 further details the ways through which the transfer of ownership was determined (

Table 6).

Table 7 presents the percentage of capital acquired in Italian firms. Of the firms in which foreign capital has entered, 335 are now fully owned by a foreign group, while only in 83 cases is the share between 50.1 and 99.9%. In 20 of the latter cases, the share is just above the majority threshold of 50%; 4.8% of the operations achieve a majority share of less than 52% (

Table 7).

Data on the value of the acquisition transaction is available for 150 of the 446 firms that passed into foreign hands. Enough time is needed to assess the orders and the magnitude of the transactions. Following the change of control, only four companies are still listed on the Italian stock exchange; ten were delisted following the takeover bid (OPA) involving, for example, Pirelli. The vast majority were not listed at the time of the transaction.

Of the 150 deals of which we know the deal value, the average acquisition value was 300 million euros. Extreme values ranged from a low of 24 million to a high of six and a half billion euros.

Table 8 and

Table 9 intercept the value ranges of the deals. 15% of the transactions had a valuation of less than 10 million. Exactly 60% of the transactions value less than 100 million; almost a third between 100 million and 1 billion; only eleven cases exceeded this threshold. For example, Intercast—a solar lens manufacturer based in Parma—was acquired for

$1730 million by France’s Essilor in a deal that also included 51% of the U.S.-based Transition Optical [

75].

On the other hand, data on corporate type is available for almost all of the sample. There were 172 Joint Stock Companies (Italian Spcietà per Azioni, SpA) involved -of which 71 were single-owner companies- and 237 Limited Liability Companies (Italian Società a Responsabilità Limitata, SRL)—of which 101 were single-owner companies; 40% of the acquired companies are in effect single-owner companies. Only one consortium and three cooperative institutions were subject to foreign acquisition (see

Table 10).

The number of employees of the acquired companies during 2010–2015 was 308 workers on average, between one and 145 thousand employees.

Table 11 shows the distribution of Italian-acquired enterprises with respect to the minimum of employees and the index of variance with respect to the average enterprise size. Taking a longer time frame into consideration, a downsizing trend of foreign-acquired firms becomes evident. The aggregate figure shows, for the firms under consideration, a sharp decline in the number of employees over the past ten years (2007–2016). From an average of 445 employees per firm in 2007, the number of employees in 2010, the first year of the survey for acquisitions, reached its lowest number in 2012, only 231 employees, and the number stood at about 296 employees at the end of the period under review (see

Table 11).

The first possible interpretation is the focus of foreign acquiring firms on those companies that have already embarked on a plan to downsize their workforce, induced by the consequences of the 2007–2008 economic crisis, reflecting a turnover of personnel affected by the acquisition. Indeed, between 2010 and 2015, the graph of employees per firm performs a “U-shaped” trajectory that approximates and stabilizes the final figure to the starting one (see

Figure 3). This trend thus described seems to be in line with those who consider the focus of foreign firms on companies that have demonstrated cost-cutting management, perhaps precisely with the aim of attracting the sights of a possible buyer [

73]. Another possible explanation concerns the structural nature of the acquired companies.

4.2. Analysis of Industrial Sectors

More than half of the acquired Italian firms engage in activities that are properly industrial. On initial examination (

Table 12), the main activity for 54% of these concerns the manufacturing sector, while one-third are engaged in services and 1/8 in trade.

A more accurate survey of the relevant sectors starts by considering the Ateco classification of economic activity adopted by Istat and based on the European Nace nomenclature (

Table 13). “Services” is the sector most involved in acquisitions with foreign buyers, an activity group that includes telephone services to software production, from audiovisual production to data processing. A quarter of the companies involved fall into this category. The second sectoral item is machinery manufacturing, and it is only slightly behind the first, with 24.4% of the acquisitions in the sample for the period. It is followed at a greater distance by the chemical sector (12.7%), the trade sector (9.7%), and several sectors that are overall not very involved.

The same analysis aimed at foreign acquiring companies shows a similar distribution, although with some major discrepancies. In the case of foreign companies, the services sector is also the most represented here, but for more than a third of the cases (35.3%), while in line with the numerosity of the targets is the machinery manufacturing sector and just slightly smaller quantitatively are the chemical and trade sectors. Banks and publishing are significantly more represented, but without significantly affecting the total (about 3%) of the sectoral distribution.

Firms involved in international acquisitions destined for Italy involve 120 sectors found in the Nace nomenclature (Rev. 2, two-digit division). Comparing the respective main business sectors allows us to identify some areas worthy of further investigation.

First of all, the descriptive exploration of the data shows an average of 5.7 acquisitions per sector, with financial services (35) and mechanics (34) at the top. While there are only slight divergences in the distribution and representation of sectors in the analysis of the aggregate data, the intra-sector dynamics are pronounced and of considerable interest.

The top fifteen sectors by number of foreign acquiring companies amount to an average of fifteen acquisitions, well above the average of just under six for the entire sample, and have at least eight completed acquisitions with a maximum of 22 deals. It follows that these sectors involve 70% of total deals. It is surprising, however, that in this representative sample, the average number of intra-sector deals, i.e., those involving firms in the same target sector, is just 27.2% on average, with very divergent cases among them (

Table 14).

The figure of acquisitions made by companies in the “financial activities” sector is not surprising. Of the 35 deals made, only in one case does the acquired company also operate in the same sector. The purely financial, even before industrial, diversification nature of this type of deal emerges. As many as five cases, for example, target the machinery sector. The latter sector is the second most represented and the one with the highest number of intra-sector transactions, accounting for 64.7% (22 out of 34). In other cases of infra-sectoral acquisitions, more than half of the cases involve food (62.5%) and software (54.5%). Few cases of business integration in the same sector, limited to electronics (14.3%), services (12.5%), insurance (10%), and even absent in publishing (0 infra-sectoral acquisitions out of eight transactions).

4.3. The Impact of the Takeovers

The research collected data about 267 companies still active in 2023 of the 446 targets of foreign takeovers over the period 2005–2015, corresponding to 60% of the initial sample. Only two companies are still quoted on the stock market in 2023. An in-depth analysis of the impact of foreign takeovers on the fundamental financial variables of each company is beyond the scope of this article. Anyhow, the aggregate evidence of the accounting statements provides an overall picture of the target companies. The analysis relies on the value of production, the net income, and the employment over the 10 years between 2013 and 2022. The research assumed the three variables to be good yet rough indicators of the performance of the companies in terms of productivity, profitability, and social wealth creation. The period is recent and includes the last years of the M&As wave under scrutiny; however, this period also includes the year of the COVID-19 pandemic that caused the shrinking of the global economy, an occurrence that reflects on the economy of most companies around the world, this sample included.

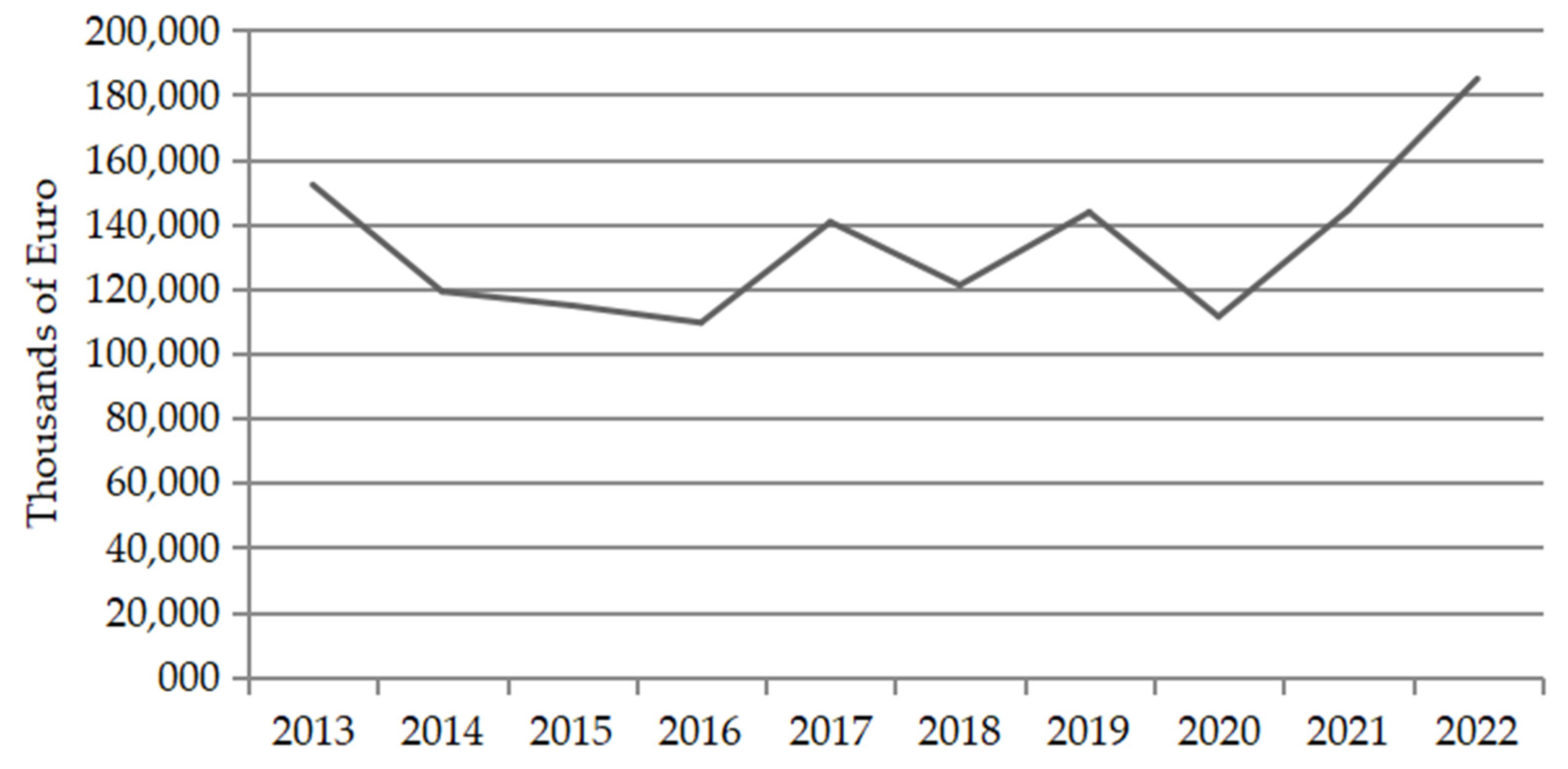

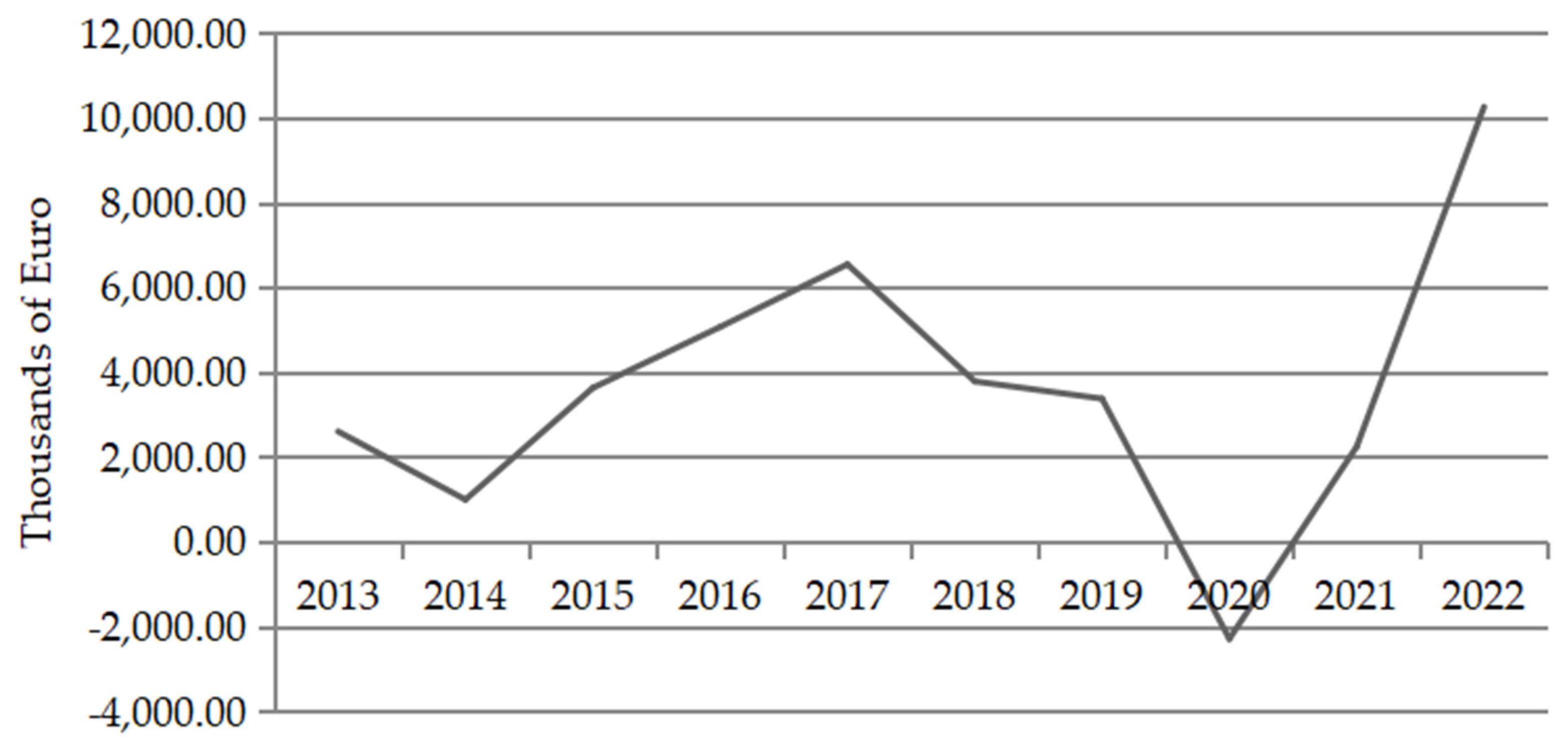

Table 15 shows that the three variables remained generally stable in the first years after the takeover and moved upward recently, particularly after the economic shock of the COVID-19 crisis of 2020 (

Table 15). The value of production (

Figure 4) fluctuates a little after 2015 and takes a positive trend after 2020. The net income (

Figure 5) initially grew positively, then suffered a bump a few years before 2020, returning right after to grow and reach its highest level. Public opinion largely considers employment to be in the greatest danger in the case of a foreign takeover, causing alarms about the impact on the social wealth of this kind of operation. The evidence, however, shows a different result (

Figure 6); the trend is positive and growing consistently through the years. While this evidence is merely descriptive and further analysis needs to properly evaluate the impact of foreign takeovers, this research can already provide insights about the overexposed concerns regarding cross-border operations.

5. Discussion

The resulting picture, although circumscribed to a period of very severe economic crisis, followed by a period of stagnation and, in some years, deflation of the Italian economy, allows us to grasp some ongoing trends that deserve further study, while other aspects, much more discussed and seemingly cogent, need to be downplayed. It must be noted that the period, which opens with the Global financial crisis (2008) and the Euro sovereign debt crisis (2010), closes again with another crisis, the global pandemic of COVID-19 and the following shakeups of the global economy and the international supply chains (2020–2021). When we look at the growth of foreign acquisitions, we see an increase in the number of these transactions, but it is difficult to speak of “invasion,” particularly so by Chinese companies. These few cases make acquisitions of control and, more frequently, move toward the placement of a minority stake in strategic enterprises. The largest transfers of control to foreign firms involve U.S. firms and those in the major European economies. Emerging countries account for a very limited share in this area.

The second point worth consideration is the relatively low average value of transactions. Many deals are less than 100 million euros. Then, evaluating the corporate form, it emerges that many of these companies are single-member, as many as 40%. A positive side of this figure is the ability, even for such small firms, to signal themselves on the international acquisition market and attract foreign capital.

Observation of the number of employees of Italian firms indicates a very clear trend. Acquiring firms are pursuing a path of downsizing, partly to be linked to the crisis period partly to signal a path of cost reduction that may attract the sights of firms interested in acquisition.

Finally, a factor of considerable interest and certainly worthy of further study is the small share of acquisitions within the same business sector. Even in the case of the transfer of company control, companies do not follow a strategy of consolidating the sector they belong to but invest in unrelated sectors, searching for technologies they do not have or pursuing radical diversification strategies. This possibility could mark another phase in the current international M&A process.

6. Conclusions

The present research has several limitations. First of all, it is mainly descriptive, as the aim of the study is to observe the behavior of companies that passed ownership to foreign companies during the last wave of M&As. The insight in this article tends to refute the belief that foreign takeover is usually a spoliation of national capabilities and dispossession of economies that reflects in loss of employment and wealth in the host country, as widely assumed in public opinion. Instead, there is no evidence of such effects, and conversely, acquired firms show stable standard economic and financial indicators with signs of improvements.

Future research can start from this baseline and go further with a comparison of the economic performance of acquired firms with other incumbents that did not pass control to foreign ownership, as well as compare another country of the target. Research may imply more quantitative methods and event studies for the analysis of the effect of acquisitions on the share price [

77,

78,

79]. Another promising avenue of research is a more detailed and granular level of qualitative analysis that includes, for example, board diversity, e.g., [

80], background [

81], and reforms [

82] in the process of acquisition. Further studies may consider the technological strategies behind cross-border M&As, which seem to overlook the core business of the acquirer [

83] and link this strategic antecedent to the post-merger consequences of cross-border acquisitions [

84,

85,

86], including the sustainability of the deals [

87].

Despite the broad scope of this research and the need for more in-depth analysis, this study contributes to our understanding of the complexities behind the multifaceted process of cross-border acquisitions and rebuts most of the opinionated considerations about foreign takeovers.