Abstract

There has been extensive research and examination dedicated to the advantages and disadvantages of entrepreneurship, both in general and specifically for African Americans. Significant research has been devoted to understanding the economic outcomes of African American men, and there is an area of opportunity to study how African American men, specifically, can leverage entrepreneurship to increase the probability of successful economic outcomes for themselves and their families. Entrepreneurial research has the potential to be leveraged to combat waning labor force participation rates and heightened unemployment rates among African American men. Leveraging the theories of Trust, Goal-Orientation, Logotherapy, and Social Identity Theory, a study was conducted among United States-based business owners. The sample size was forty-one African American male business owners. The results demonstrate how these African American men have leveraged entrepreneurship to build social capital and wealth, while improving their standard of living, as well as highlight the hurdles and barriers they have endured during the process of business ownership. The majority of African American owned business are owned by African American men, and this study provides insights into the phenomenology of African American male entrepreneurs.

1. Introduction

In 2021, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) released a report that estimated the annual cost of joblessness among African American men at USD50 billion [1]. Scholars and economists have sought to understand the reasons for the high levels of joblessness and have uncovered a number of potential sources. For instance, African American men experience higher levels of unemployment [2], lower levels of collegiate degree attainment [3], and lower levels of entrepreneurship compared to other demographics in the United States [4].

Other potential reasons point to historic discrimination, leading to economic disparities. For example, in lending and banking, there is a twenty-nine-percentage point gap in home ownership between African Americans (45.3%) and White Americans (74.6%) [5]. The differential in homeownership is relevant, specifically in the context of entrepreneurship, as research suggests that from four percent [6] to over seven percent [7] of small businesses are initially funded, primarily, by a home equity line of credit.

Furthermore, African American men are incarcerated at a disproportionately higher rate, which is associated with lower probabilities of being employable, with some research estimating up to sixty percent of formerly incarcerated people being unemployed a year after release [8].

Given these staggering statistics and the employment challenges faced by African American men, some of these men have taken matters into their own hands and sought opportunities in entrepreneurship. For many, becoming an entrepreneur is the culmination of a career of building, developing, and honing a skill, or a set of skills, and determining that one’s value exceeds the compensation that they may receive from traditional employment. While this may be the conventional path to entrepreneurship for many, survivalist entrepreneurship has, at different points throughout the United States’ history, represented a necessary path to economic viability for many African Americans. According to Boyd [7], who discussed the concept of survivalist entrepreneurship among African Americans in his research on the Great Depression, survivalist entrepreneurship occurs when a person or a group of people become business owners as a direct response to the lack of employment opportunities in their community and the necessity of finding an independent means of generating income. In a modern context, survivalist entrepreneurship can be defined, specifically as it pertains to African American men, as leveraging entrepreneurship to combat suboptimal economic and employment opportunities, for the benefit of themselves, their families, and their communities.

This study examines whether survivalist entrepreneurship still applies in the very much changed environment of today and accomplishes so in a qualitative manner by directly examining evidence as coming out directly from the mouths of those involved. This qualitative approach also addresses some of the critique levied by Fitch and Myers [9] against the analysis performed by Boyd [7], and, critically, we analyze not only the “sheltered from outside competition” categories.

The results of our qualitative study also stand in contrast to other critique on the theory and, specifically, an interdisciplinary review by de Groot et al. [10] on survivalist entrepreneurship among women entrepreneurs in the informal food sector, which found little support for the idea that access to energy (resources) promotes entrepreneurship.

As the volume of research which disaggregates entrepreneurial data of African American men can be sparse and difficult to identify, research that offers comparative, non-aggregated data could provide a wealth of knowledge on how to support specific demographics more effectively. Additionally, providing empirical data can help support targeted strategies to increase entrepreneurship in populations in which business ownership is not as prevalent or where there is an opportunity but potentially not the knowledge and/or resources available to participate. This research seeks to address this issue and understand the foundations of entrepreneurship for African American men.

Specifically, we seek to bridge the gap in survivalist entrepreneurship scholarship among African American men in the United States, as this group has historically endured a harsh employment climate. This research employed quantitative and qualitative methods, including regression analysis, qualitative thematic analysis, and qualitative-grounded theory analysis, with the aim of attaining a phenomenological perspective on how entrepreneurship has been leveraged to positively impact the economic outcomes of African American men.

1.1. Literature Review

Much of the focus of modern research on survivalist entrepreneurship is based on how it can be leveraged to provide additional economic opportunities to citizens of developing nations [11,12,13,14,15], most specifically among women in developing nations [10,16,17,18,19]. For African Americans, the discussion on survivalist entrepreneurship is based on Boyd’s [20] seminal work, researching survivalist entrepreneurship among African Americans during the Great Depression, but not much has been explored in a modern context. Within this research, Boyd discusses the “Simple Disadvantage Hypothesis”, which postulates that having a disadvantage in the labor market increases the probability of entrepreneurship within the disadvantaged group. The Simple Disadvantage Hypothesis was derived from The Disadvantage Theory of Business Enterprise, which was a hypothesis meant to explain why minority groups, impacted by discrimination, had higher-than-average rates of self-employment [21].

A further expansion of the Disadvantage Theory of Business Empire sought to identify that, in addition to an environment with restricted employment opportunities for a minority group, the resulting scarcity of resources had a contributing factor to the increased probability of entrepreneurship. With this additional context, the “Resource Constraint” variant of the Disadvantage Theory was developed [22,23]. Expanding beyond “Resource Constraint”, Light and Rosenstein outlined the concept of “Resource Disadvantage”, which proposes that, when the availability of resources becomes too scarce, the group in question, having limited options, is more likely to become self-employed in an informal (i.e., potentially illegal) way, as opposed to starting a traditional business.

Notably, we do not advocate for self-employment in an informal economy; rather, we argue that a litany of other factors has created an environment for African Americans that constitutes a real discussion regarding whether African American men should embrace entrepreneurship, in a survivalist context, in a formal capacity, in order to improve their economic standing and viability. The importance of entering this arena in a formal capacity cannot be understated, as studies indicate that minority-owned businesses are more likely to hire other minorities, leading some scholars to believe that fostering minority business growth could be an effective tool for reducing minority unemployment and increasing labor force participation [24,25,26]. Research suggests that there are a number of factors that influence the likelihood for African Americans to engage in entrepreneurship. Below, we highlight some of these factors to provide the foundation for our research. Namely, these factors are gender, academic achievement, mentorship, and the pressures of entrepreneurship.

1.2. The Literature on Survivalist Entrepreneurship

Survivalist entrepreneurship, expanding on earlier studies in sociology [21], is the notion that “disadvantages in the labor market (i.e., unemployment or underemployment) often compels members of the oppressed ethnic groups to find an independent means of livelihood” [20]. Survivalist entrepreneurship enables many poor people who lack access to resources to improve their lot, but studying it requires recognizing that it is distinctly different from growth-oriented entrepreneurship [27].

Examining survivalist entrepreneurship among African Americans during the Great Depression, Boyd [7], by quantitively examining employment records from the decennial census of 1940, found partial support for the hypothesis. That support was found, however, only in professions where African Americans were “sheltered from outside competition” (p. 975) because of racist behavior by the majority population refusing to provide such services to African Americans, such as barbering among men and beauty culture among women.

1.3. Gender Differences among African American Entrepreneurs

While research indicates that African American women are the fastest-growing demographic of business owners in the United States [28], the majority of African American-owned businesses are owned by African American men. Out of the African American-owned businesses in the United States, 53% were majority-owned by men, 39% were majority-owned by women, and 8% had equal, or joint, male–female ownership [29]. A study by Gibbs [26] highlighted, comparatively, the economic demographics of African American men and women entrepreneurs. Among African American entrepreneurs, African American men were more likely to be college-educated, their firm was more likely to have endured beyond the three-year mark, the revenue was more likely to be higher at all revenue strata above USD100,000, and they were more likely to employ full-time workers at all employment strata other than zero full-time employees. An interesting factor in the study was the indication that African American men were more likely to have received mentorship than African American women.

Research also indicates that African American business owners have an average annual salary ranging from USD50,539 [30] to USD70,391 [4]. While this represents the lowest average annual salary of major ethnic groups in the United States, it is significantly higher than the per capita income (USD29,385) and median income (USD50,001 for men and USD44,131 for women) than the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [31] estimates of African Americans’ annual salaries. Collectively, the gender data on the average annual salary range for business owners were aggregated in terms of gender, ethnicity, and age. Based on the data, we could infer that, with African American men having higher average salaries and businesses which generate more revenue, African American men are more likely to represent the higher end of the salary range than African American women, intra-ethnically.

1.4. The Impact of Academic Achievement on Entrepreneurial Outcomes

Collegiate degree attainment varies across gender and ethnic strata. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data indicate that African American men lag White, Hispanic, and Asian men and women. In particular, they lag African American women at the Associate and Bachelor’s degree levels and White men and women, Hispanic women, and African American women at the Master’s level [3]. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) [32] indicate that the unemployment rate for college degree holders is lower, on average, than for high school graduates. The data also indicate that, as of November 2020, the unemployment rate was 6.7% at the national level, 4.1% for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 4.7% for those with just a bachelor’s degree, and 7.4% for those who were high school graduates. Taken together, it is not difficult to identify some of the employment woes of African American men when comparing unemployment data with educational data.

The increased probability of business ownership correlating with collegiate degree attainment has been known for decades, as research from Evans and Leighton [33] indicated that self-employment had a higher probability among individuals who were more highly educated.

While academic achievement and other traditional factors correlate to higher levels of entrepreneurship, we would be remiss if we did not discuss the importance of strategic academic attainment. In a study by Georgetown University, Carnevale et al. [34] found that there tended to be a concentration of African Americans in the lowest-earning degree fields. Out of the top 10 majors by percentage of African American bachelor degree holders, none fell within the top 10 highest-earning majors for African Americans. Human Services and Community Organization and Social Work, which represented the majors with the second- and third-highest percentage of African American degree holders, both fell within the 10 lowest-earning majors for African Americans. Seven of the top ten highest-earning majors for African Americans included engineering, none of which were in the top ten highest-earning majors. For African American men specifically, the path to academic and economic success already has significant hurdles. Academia, if leveraged properly, can be a pathway to greater professional success, and the probability of greater success increases when degrees with the highest returns on investments are prioritized.

1.5. The Impact of Mentorship

Mentorship is an integral component in supporting the needs of at-risk youth, with research indicating that this is especially true when the program is aimed at African American boys [35]. The act of mentorship, when directed toward the goal of developing novice entrepreneurs, has been found to be an integral component to the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) and other entrepreneurial skills [36,37,38,39,40]. In addition to ESE and other entrepreneurial skills’ development, mentoring relationships have been found to positively impact a mentees’ emotions and cognition, their ability to create more ambitious goals and improve their skills in relation to identifying business opportunities, and reduce stress and the feeling of isolation [41,42,43].

Hu et al. [40] found that experiencing mentorship from an individual with parallel motivation and learning can increase the ESE of the mentee by receiving guidance from one with similar experiences and skillsets, as well as having a mentor who is able to successfully motivate the mentee towards entrepreneurial activities. The advice and guidance of a strong mentor can also help the new entrepreneur avoid costly financial mistakes [44,45]. Moreover, as observed by Festinger [46] in his social comparison theory and as bolstered by Bandura’s [47] social cognitive learning theory, from an ESE standpoint, the more likely an individual perceives themselves as similar to their role model, the greater the impact on their ESE [48].

1.6. The Often-Overlooked Realities of Entrepreneurship

It should be stated that entrepreneurship is most certainly not for everyone. While the life of the entrepreneur tends to be glamorized, there are significant challenges that impact the daily life of the entrepreneur that are frequently overlooked. For instance, the borderline extreme measures that are required for successful entrepreneurship have been known to create tension and strife within the family of the entrepreneur [49], with Kets de Vries [50] concluding that the personality types which often thrive in an entrepreneurial environment are intense enough to lead to frequent divorce.

The failure of an entrepreneurial endeavor has also been documented to create deleterious effects, not just on the mental health of the entrepreneur, but also on the family of the entrepreneur [51]. Depression can arise from the grief related to investing extraordinary levels of time, energy, and money into a company that ultimately fails to being an enduring organization [52]. There is not a large body of research on the impact, outside of the financial one, that entrepreneurship has on the life of the entrepreneur, but the findings in one study indicate that entrepreneurs, when compared with senior managers, are more likely to report social isolation, job insecurity, and other symptoms of burnout such as illness, stress, and fatigue [53]. Among the most frequently discussed downsides of entrepreneurship are the failure rates. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate one-, two-, five-, and ten-year small business failure rates of twenty percent, thirty percent, fifty percent, and seventy percent, respectively [54]. While failure rates of nearly one-third within a two-year period and nearly three-fourths within a ten-year period are daunting to say the least, the risk of starting a business does not seem as perilous for a demographic that has historically experienced the highest rates of unemployment and among the lowest rates of labor force participation.

Taken together, gender, academic achievement, mentorship, and pressures provide insights into foundational differences in entrepreneurial engagement among African American men.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method

Forty-one African American male business owners were interviewed, which amounted to over thirty-five hours of interviews. The interviewed informants were sourced primarily from LinkedIn, with forty being sourced through LinkedIn and one being referred. Nearly 900 LinkedIn requests were sent, with 315 business owners accepting the request. Out of the 315 who accepted, 65 agreed to be interviewed, with 41 ultimately participating in the study. Ultimately, 35.8% of the LinkedIn requests were accepted, 7.39% agreed to be interviewed, and 4.66% were interviewed. The people who agreed to be interviewed after the interview window had been closed were not included.

All the entrepreneurs who agreed to be interviewed were male and African American, operated a US-based business, and had at least one employee or a partner employed by their firm, not including themselves. These entrepreneurs owned businesses across twenty-one states and the District of Columbia. Thirteen distinct business industries were represented across the interview pool, with Technology and Construction representing the highest concentration of participants, at eleven and ten, respectively.

2.2. Interview Protocol

The semi-structured interview protocol was reviewed by a panel of seven informed individuals and then received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval in March of 2023. The protocol included a series of open-ended questions to provide structure and guidance to the conversation. As no qualitative theory or hypothesis had been identified prior to the interviews, the objective of the interview protocol was to develop a novel understanding regarding entrepreneurship among African American men. Thus, the reasoning protocol for this interview strategy was inductive.

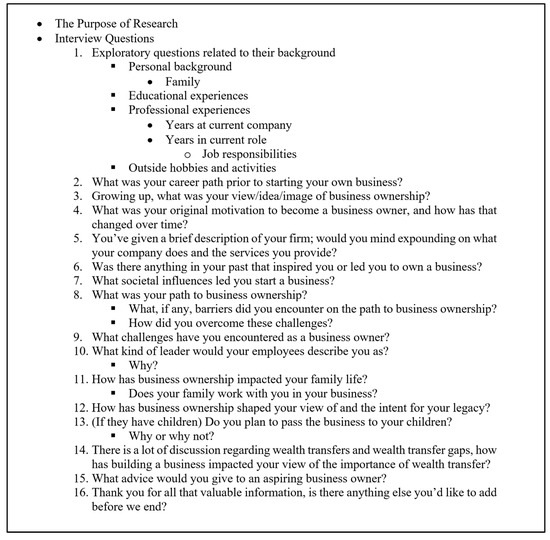

The protocol was structured to identify the key factors that had led the participants towards entrepreneurship, including their inspiration and/or motivation, early-childhood perspectives on entrepreneurship, career and professional experience attained prior to entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial influences, barriers and challenges to entrepreneurship, the familial impact of entrepreneurship, and considerations related to wealth accumulation, preservation, and transfer. Figure 1 shows the interview protocol utilized during this research and provides the complete protocol. In total, over 35 h of interviews were accumulated.

Figure 1.

Interview protocol.

2.3. Interviews

The interviews were conducted over a sixty-day period. Each interview began with the informants providing background on themselves and their family, prior to moving onto questions related to their entrepreneurial experiences and the impact that those experiences were having on their personal lives. All the interviews were conducted via Zoom in order to leverage its playback features for in-depth analysis as well as have transcriptions of each interview. In addition to the transcriptions, field notes were taken during each interview to identify themes and relevant or timely proclamations and capture feelings and emotional context in real time.

2.4. Qualitative Research and Analysis Methodology

We used a thematic analysis strategy, specifically in the vein of Miles and Huberman [55]. The ideology of leveraging thematic analysis was to identify high-level themes, patterns, and commonalities expressed throughout the interview process and develop a framework, derived directly from the phenomenology of African American male business owners, which could be utilized for future research and strategy implementation.

The analysis was a four-stage process. This began after repeated review and familiarization with the data by reviewing the interview transcripts and field notes. After data familiarization, the first stage of analysis—coding—began. The act of coding included creating labels or “codes” that described meaningful aspects and components of the interviews. More specifically, the codes were leveraged to identify and describe the thoughts, ideas, and feelings expressed throughout the interviews. Once the codes had been created, they were grouped based on high-level patterns and themes and compiled into cluster themes. The cluster themes represented the first level of thematic identification.

After further analysis and the identification of deeper patterns, the cluster themes were grouped and compiled into main themes. The main themes were the first level of thematic grouping that included thematic depth and ideological richness and were the cornerstone of the thematic process, as they represented the first true reflection of identifiable trends and/or patterns in the data. The final stage of analysis included grouping and compiling the main themes into global themes. These global themes identified an overarching phenomenon that impacted a significant segment of the researched demographic in a meaningful way.

3. Results

3.1. Global Themes from the Research

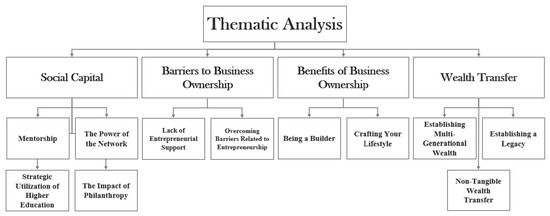

A total of 487 codes, 29 cluster themes, 11 main themes, and 4 global themes were identified during the analysis. Table 1 reflects the coding distribution and aligning themes for each global theme. Figure 2 reflects the coding map of the global themes with their aligning main themes. The overarching phenomenon that emerged were the global themes of social capital, the barriers to business ownership, the benefits of business ownership, and wealth transfer.

Table 1.

Distribution of thematic coding schemes.

Figure 2.

Interview analysis thematic coding scheme.

Figure 2 shows the coding map of the global themes with their aligning main themes. The overarching phenomena that emerged were the global themes of social capital, the barriers to business ownership, the benefits of business ownership, and wealth transfer.

3.2. Catalysts for Entrepreneurship

This research identified a variety of catalysts that had led these entrepreneurs towards business ownership. These included, but were not limited to, parental inspiration, familial exposure to entrepreneurship, exposure to entrepreneurship in college, and a motivation to receive one’s worth in compensation due to poor corporate culture. An interesting and recurring theme regarding the catalysts for entrepreneurship was how frequently the discussion focused on the impact of fathers in inspiring entrepreneurship. Fathers were the most commonly discussed inspiration for sparking entrepreneurial aspiration, and many of the entrepreneurs were striving to be that inspiration for their children.

3.3. Social Capital

Entrepreneurship being a conduit for building social capital with a community was identified in four specific ways. These became the foundation for the main themes of mentorship, the power of the network, the strategic utilization of higher education, and the impact of philanthropy. In addition to these main themes, social capital had ten aligning cluster themes.

3.3.1. Mentorship

Throughout the interview sections relating to mentorship, 40.9% of the respondents discussed leveraging mentorship for advice and guidance, with 25% stating that they were actively seeking business mentorship and 13.6% discussing their plans towards building a platform of some kind to facilitate entrepreneurial mentorship. The increased ESE resulting from mentorship had been previously discussed, and this was present within the interviews. Included below is an excerpt from an interview where the respondent discussed receiving council from a mentor and how that helped motivate him to pursue what would ultimately become his first successful business:

“I tried some different business endeavors, nothing stuck, like […]. I remember a great advisor for myself, and mentor, over the summer of 2019 said, […], the idea that you shared with me back in 2012, I really think you should explore it”.

As in previous research [56,57,58], the interviewed entrepreneurs especially benefitted from mentorship, as the skills needed to be successful in start-up usually have to be possessed by the business owner initially, and the skills needed tend to be far broader than those required for other economic endeavors. Research also indicates that entrepreneurial mentorship can inspire and motivate a mentee towards entrepreneurial activities [59]. Corroborating the motivational literature, one interviewee stated the following:

“Well, I had always heard, kind of going back to that mentor who talked to me about getting in the business and doing things on my own, that stayed with me. And I thought that if I could find a career path where my income wasn’t limited, and I had always read that the entrepreneurs generally are able to create more wealth than those that just have a regular 8 to 5 job or 9 to 5 job. So that prompted me to really thinking about what could I do to kind of earn a living and build wealth”.

Another benefit of mentorship highlighted in previous research is that, discussing access in a more traditional sense, the scarcity of direct access to key resource-holders and the lack of a social and professional network that can refer and vouch for you can play a significant role in an aspiring entrepreneur’s ability to access resources for creating their business venture and can have adverse impacts on success [60,61,62]. Relationship building is vital to business success, and the result of relationship building is access to social and professional networks. Mentorship could be one of the only mechanisms that can offer access to networks from which entrepreneurs may have been previously excluded. This came up in another discussion.

“From a business side, entrepreneurship side, and it’s still this prominent today, when you talk about access to capital, I sit in a lot of rooms where folks will say, ‘Well, we all know that the access to capital pipeline is friends and family first’. Well, hell if you black, and you ain’t got no rich friends or family, where you gonna get the money?”

3.3.2. The Power of the Network

Social capital theory posits that membership within a network comes with privileges such as access to the social resources that have been amassed within that network [63,64,65]. In order for these networks to be effective, Portes [66] has indicated that the social network requires development, which is facilitated through strategic investment which fosters the institutionalizing or assimilation of group relations. Some research indicates that the existence of social capital can create an environment that fosters the efficient exchange of information and knowledge [67].

The entrepreneurs we interviewed discussed leveraging their existing network to identify and capitalize on opportunities. These opportunities included identifying financial institutions that were more likely to provide financing, former colleagues who reached out to indicate interest in the utilization of their services, and the ability to contact people in the network who could assist one with finding answers and solutions more quickly. Within the power of the network theme, 43.6% of the respondents discussed collaborating with others for greater economic output, 25.6% discussed leveraging networks to identify opportunities, and 17.9% outlined plans for building the infrastructure to connect other business owners, with the goal of creating new networks.

3.3.3. Strategic Utilization of Higher Education

The financial realities of most African Americans, more so for African American men, demand a strategy that goes beyond the generic edict of “going to college”, into the strategy of prioritizing going to college, or trade/technical school, with a strategy for cost minimization, selecting a degree or certification for career prioritization, and building a network for professional optimization. An entrepreneur who was in the midst of completing a PhD program spoke of college as “the ultimate networking” tool, as it could provide one with access to networks of people with a broad range of skills which one could not only leverage over the course of their career but also be able to provide reciprocal value to, if the individual’s expertise was required instead. Here is an excerpt from that interview:

“I think education, for me, educational achievement is learning from other people, and I think we can learn from professors obviously because they’re in a position for a reason. But for me, especially in the PhD program, even in law school, I learned so much from other people and how they lived their lives and how they thought and their experience. Because I don’t know people in finance, but people in my cohort who work in that, you know, I’m listening to how like, wow, I never thought of it that way. Or how they’re in, you know, higher education. I never thought of it that way, how they’re into agriculture, how they’re into, I don’t know, any different role that they’re in… It’s the ultimate networking, it’s the ultimate LinkedIn. I mean, you’re graduating with two hundred other people who are going to be lawyers. What better networking tool could you ask for where you graduate with ten other people who are going to be PhDs? What else could you ask for to be able to pick up the phone, if someone calls you and say, Hey, you know, I need an expert that deals in quantitative research findings of, you know, saunas or whatever, and you’re like, oh, I know the person”.

Out of the respondents who discussed how education played a role in their path to entrepreneurship, 32.1% stated that they were introduced to someone in their professional network while in college, 28.6% stated that their first exposure to entrepreneurship occurred in college, while 14.3% stated that they considered entrepreneurship for the first time in college.

3.3.4. The Impact of Philanthropy

An aspect of philanthropic giving that may be detrimental to the psychology of giving, among African Americans, is what actually counts as philanthropy. Bell [64] found that, while African Americans have a tradition of giving, specifically to organizations such as churches, community organizations, and socio-political/political organizations, most African Americans do not perceive these endeavors as “philanthropy”. Further, the concept of philanthropy, according to Bell’s research, in the African American community, is considered the domain of institutions and/or exceptionally wealthy individuals. When discussing philanthropic impact, the concept of developing a philanthropic infrastructure at the institutional level was a prevalent theme. The focus turned to three primary components: business-based philanthropy, education-based philanthropy, and financial literacy-based philanthropy. Among the entrepreneurs who discussed leveraging entrepreneurship for philanthropic purposes, 35% stated they planned to facilitate wealth transfer, in some form, through philanthropy, 35% stated they planned to fund education and financial literacy, and 20% stated that they planned to utilize wealth to create social equity.

3.4. Barriers to Business Ownership

Significant challenges to successful entrepreneurship were discussed throughout the interview process. The primary obstacle that was consistently discussed was the lack of support. The entrepreneurs discussed their strategies for overcoming this and other barriers.

3.4.1. Lack of Entrepreneurial Support

The theme of lacking access to capital, which generally presented in the form of a lack of access to institutional, traditional, and/or legacy financial resources, was the most enduring theme. While the focus of many researchers has been to identify and highlight the issues related to disparities in institutional access to capital, it should also be noted that having access, while beneficial, may not be as important as the type of access. One of the entrepreneurs highlighted another potentially less well-known component in institutional financing. At the time of the interview, his organization was approaching its 30-year anniversary. Below is an excerpt of our discussion around access to capital:

“Yeah, and then regarding lending, we had basically receivables-based financing, you know, where you have to find someone who offers the product, and you pay an elevated fee, but building to scale gave us the volume of business to-and as we start to build backlog, as we call it in our business, as we start to build backlog, which is an intangible asset from an accounting standpoint, but it evidences, you know viability”.

The interesting aspect of this discussion was accounts’ receivable financing, also referred to as AR financing. AR financing can be a beneficial tool and is primarily the short-term financing needed for short-term funding requirements. The short-term nature of this financing is due to the fee structure, which tends to be significantly higher than traditional financing. This entrepreneur could not secure traditional financing for over fifteen years, even though his business was profitable almost from its inception. The long-term costs associated with these types of financing put a severe strain on already limited resources. This story is, unfortunately, common. Difficulties in securing access to traditional financing are frequent and common across the board for new ventures. Many of the entrepreneurs experienced these obstacles, even when they were able to provide documentation of consistent year-after-year profitability.

3.4.2. Overcoming Barriers Related to Entrepreneurship

While financial support was the most recurring theme for entrepreneurial obstacles, it was most certainly not the only one. During discussions related to barriers and challenges, many of the entrepreneurs discussed their strategies for successfully overcoming these barriers. The discussions included learning how to effectively collaborate with others, incorporating partnerships, building business credit, focusing on professional self-development, increasing acumen in time management, and having determination to overcome adversity. Similarly to aspects of social capital, one of the most prominent strategies utilized was building, growing, and leveraging networks. Once the infrastructure of professional support was in place, many of the entrepreneurs were able to tap into that network to find business advocates, forge partnerships, and lay the foundation for collaboration with larger organizations that had the effect of fostering growth and expansion. Here is an excerpt from a discussion on overcoming obstacles:

“Building allies, having champions within whether it’s in financial institutions, whether it’s with the clients that you’re working with, or other folks that can speak for you when not at the table. They can speak to your character, your ability to execute, your commitment to community, and those are all been things that I’ve been able to, you know, been able to knock down barriers…and blessed you know with a good network of people that have, you know, vouched, and believe in the work that we’re doing”.

While partnership, networks, advocates, and other measures provided support, potentially the most important theme for overcoming challenges was related to resilience. Virtually every entrepreneur discussed how, while there were many ways to overcome challenges, the most important way was the mental one—having creativity, having grit, and having the fortitude to overcome extreme challenges and the adversity which comes with an endeavor as challenging as entrepreneurship.

3.5. Benefits of Business Ownership

While the barriers related to business ownership should be taken seriously, the potential benefits provided the entrepreneurs with significant motivation to take on the previously mentioned risks. The primary components within this theme were “Being a Builder” and “Crafting Your Lifestyle”.

3.5.1. Being a Builder

Similar to other ethnic groups, within the African American community, African American men are more likely to be entrepreneurs and have mature businesses, their businesses are more likely to generate higher annual revenues and they are more likely to have businesses that have employees beyond the business owner [68]. In a study of African American business ownership, Gibbs’ [68] research indicates that, out of the careers which have a higher probability of enhanced compensation, African American men are more likely than African American women to own businesses in that industry. Some examples include construction, distribution, logistics, Transport, and IT and Engineering, which have male-to-female ownership ratios of 17% vs. 5%, 14% vs. 4%, and 9% vs. 4%, respectively.

The one industry in which African American women have a significant ownership advantage is sales, services, and consulting, with a female-to-male ownership ratio of 79% vs. 53%. These numbers indicate that African American men may have a unique opportunity in that their ability to start a business may be greater than that of African American women, as men have more opportunities across the blue- and white-collar spectrum of industries. One of the requirements of our study for the business owners to be interviewed was that they needed to have at least one employee or partner, other than themselves. Being able to provide employment for others was prominent in the discussions and aligns directly to the theme of “Being a Builder”.

3.5.2. Crafting Your Lifestyle

Several entrepreneurs discussed the advantage of not only controlling their own employment but also having more flexibility with their time than would be possible with traditional employment. Having the flexibility to sit on boards, not being tied to a desk, and, once organizational maturity has been achieved, being able to manipulate their professional time to accommodate prioritizing other aspects of their life, such as family, were prevalent throughout the interviews. To the business owners, one of the most important benefits was the ability to spend more time with family, specifically children. Several of the interviewed entrepreneurs were fathers, and, while the rigorous schedule of entrepreneurship meant that they could not always be available for events in the lives of their children, they felt that they were able to accomplish so at a higher rate than if they had been constrained by traditional employment. Activities such as the pickup and drop-off of children at school and being able to model the behavior of a professional while exposing their children to their organization(s), as well as the ability to see their children grow up, were frequently discussed. Here is an excerpt from an entrepreneur who highlighted the familial benefits he received from entrepreneurship:

“I think it’s been great. I think it’s given me an opportunity to see all of my children, for the most part grow up. And I think it’s probably atypical for, you know, the males to be able to be at home with the children and see them grow up because normally, in this culture, I can’t speak for everyone, someone’s going to a nine to five. And so the fact that I have the ability to see them grow up, be able to drop them off from school and pick them up, go to Taekwondo, and things of that nature, I think has really impacted them in a positive light because at this point, aside from my oldest, all they know is daddy being with them and running a business as opposed to daddy going to X, Y, and Z for X amount of hours and I’m going to see you at seven o’clock when you get off”.

3.6. Wealth Transfer

The entrepreneurs were very open about the pride they had in being able to afford their family a comfortable lifestyle. Many spoke of the opportunities, socially, educationally, medically, and professionally, that they were able to afford their children, which the entrepreneur had not received as a child, and the joy they had in seeing their children thrive in economic stability.

Many individuals and families strive to build, grow, maintain, and transition wealth across multiple generations. While wealth is often associated with income, true wealth is distinct from earned income. Oliver and Shapiro’s [65] research indicates that the distinction between income and wealth lies in the fact that income is a resource pipeline, generally from avenues such as wages, salaries, and commissions earned for services rendered or resources derived via interest or dividend payments from pension funds, governmental payments, or investments, whereas wealth is resilient, able to provide resources and opportunities despite a failure of income stream(s), and more likely to be associated with quality of life, economic well-being, and economic access.

Thomas et al. [66] further separate the constructs of income and wealth, as their research indicates that wealth and the accumulation of wealth are longitudinal processes that occur over the course of a lifetime. The accumulation and preservation of wealth are of such importance that they have led some scholars to believe that, in regard to intergenerational economic mobility, wealth is more important than income, as wealth and personal income are weakly correlated [67,69]. Throughout the interviews, three primary aspects of wealth and the transfer of wealth were prominent themes.

3.6.1. Establishing Multi-Generational Wealth

One of the entrepreneurs interviewed discussed how entrepreneurship had helped evolve his thought process and given him hope to see a path to generational wealth, as opposed to hearing about it on social media. Several participants discussed the evolution of their process, as entrepreneurship was initially a means to labor and income but progressed to an instrument of wealth and prosperity. Several entrepreneurs discussed increasing their own understanding of the financial tools designed to facilitate wealth transfer and how they are currently leveraging or are planning to leverage these tools for their children and grandchildren. The theme of increasing financial literacy was significant, as several entrepreneurs discussed not only increasing their own financial literacy but also creating an avenue to have discussions with family members regarding financial matters. One entrepreneur discussed creating a family investment club, which helped create additional familial wealth.

3.6.2. Establishing a Legacy

Out of the many variations of legacy which were discussed, a few were more prevalent than others. Many of the entrepreneurs discussed how their reputation and standing in the community was positively impacted by entrepreneurship. The legacy discussion fell into three primary categories: business-based legacy, in which the entrepreneur viewed the success and reputation of their business as their legacy; heritage-based legacy, in which the entrepreneur believed in creating a tradition of inspiring and motivating others towards entrepreneurship; and philanthropic legacy, in which the entrepreneur perceived their legacy to be based on investing in their community. The desire to leave a positive impact on their community was a recurring theme. This came in the form of feeling an obligation, as a community leader, to provide for and support others in the community, faith-based organizations, and a more positive environment and take on initiatives such as affordable housing in underserved neighborhoods. Several entrepreneurs had already created charity or non-profit organizations, designed around a variety of causes, with many based on supporting the local community. Many others had plans to achieve so in the future.

3.6.3. Non-Tangible Wealth Transfer

While wealth is a resource which is frequently viewed as tangible, often monetary, and somewhat immediately accessible, many of the entrepreneurs we spoke to discussed non-tangible wealth that they planned to pass onto their offspring, greater family, peers, and community. Knowledge, skills, and values were prominent themes throughout the discussions. The ability to transfer wealth in ways beyond financial instruments was integral to the wealth transfer philosophy of several entrepreneurs. This manifested itself in the areas of belief-based wealth transfer, which was focused on instilling values, morals, and ethics, education-based wealth transfer, which was focused on teaching their family and community about improving their business acumen and financial literacy, and learning-based wealth transfer, which was focused on transferring knowledge as a form of wealth transfer. Wealth transfer beyond financial instruments and into education, teaching, and values was summed up by one entrepreneur who discussed his thoughts on extending wealth transfer beyond monetary instruments. He stated the following:

“Not wealth as intangible assets and buildings and land, right? There are some intangible wealth, like a work ethic, right? And a sense of family and morals and those things”.

4. Discussion

This study examined the factors related to the successful adoption of entrepreneurship as a primary career path and income source for African American men and how entrepreneurship impacted their career, economic stability, familial structure, and legacy. This study also contributes to the existing literature on how a variety of factors impact the social viability and economic stability of African American men and how, in their view, the creation of a culture of entrepreneurship may be an effective tool that can combat the disparate wealth outcomes and negative economic outcomes of African American men. There were several interesting findings throughout our research. Some of the key takeaways from our research are included below.

Notions and Purpose of Entrepreneurship

African American men were likely to indicate that entrepreneurship had a positive long-term impact on their career, that it was a childhood aspiration, that they were inspired by their father, and that they were likely to indicate their intention of leveraging entrepreneurship to invest in their community.

The theme of fatherhood and how it inspired many of the entrepreneurs was unexpected, but interesting. Having a role model who modeled the behavior of a professional who was in control of their career, supported their family, and created opportunities for their offspring was a positive factor in the decision to enter entrepreneurship for many of the men interviewed, and it spotlights the positive impact that fathers can have on the economic outcomes of their offspring.

Career Control

The African American men interviewed were likely to report leveraging entrepreneurship due to a lack of employment opportunities and indicated that they experienced difficulties related to staffing their organization. They also emphasized the power of mentorship, creating a network, and the importance of focusing on continued self- and professional development to increase their business acumen.

Economics, Wealth, and Legacy

The African American men we interviewed were also likely to tie their legacy to transferring wealth to the next generation, leverage entrepreneurship as a tool to afford themselves financial security, and improve their standard of living.

While nearly all the entrepreneurs interviewed expressed philanthropic intentions, several entrepreneurs went as far as to create non-profit organizations to invest in their communities more effectively. An unintended, but welcomed, finding in this research was the philanthropic voice of African American men. The introduction highlighted a study that indicated that the joblessness of African American men costs the United States’ economy approximately USD50 billion. This research shows the measures that some African American men are taking to invest in their communities and provide the environment to increase the economic outcomes of others either directly through their business (i.e., providing employment opportunities), through mentorship, providing financial literacy, or by creating philanthropic organizations that focus on community building.

Brought into a broader theoretical perspective, there is no doubt that entrepreneurship can play a key role in improving people’s lives; however, most past research efforts on the topic have ignored the role of race by treating it as an exogenous variable rather than a critical contextual one [70] and by conducting research by adopting a “race neutral lens” [71]. In this study, we included this aspect explicitly and then compared our study results with other disadvantaged communities. Including race is important because studying entrepreneurs requires understanding their social environment, given the racial disadvantages and social structures involved [71]. Despite calls for including a racial lens, a recent review of the themes in the entrepreneurship literature [72] did not find it as a theme in that line of research. The results indirectly support the argument [70] that studying entrepreneurship may require including “the structural underpinnings of racial disadvantage for underrepresented minority entrepreneurs” (p. 492).

Comparing our results with “under-resourced communities” in South African townships [73] is telling in view of the short-term emphasis of those interviewed in those townships. Unlike in the US, the informal entrepreneurial sector in those townships is often just “a buffer against starvation” and, therefore, much less developed. As a result, entrepreneurs often leave their endeavors once they gain employment in the formal sector. Among those interviewed in the townships, the primary drivers to becoming an entrepreneur were the entrepreneur themselves and the surrounding setting. The former dealt with the need to provide for one’s family, ethical conduct, strong work ethics, financial independence, being purposefully engaged, having an altruistic mindset, showing perseverance, being creative and innovative, having a religious mindset, and lacking financial training. The latter dealt with family or associate support, the fact that the township space was not conductive because of poverty, crime, and drugs, the lack of social cohesion in the township, and an “extremely ineffective” government. Presenting these results in a positive deviance framework (i.e., strategies employed by some individuals who prosper despite a harsh and unconducive situations), Toit et al. [73] concluded that what made the survivalist entrepreneurs successful was their being actively involved in changing their own lives.

This comparison also sheds light on another distinction. While Toit et al. [73] treated the survivalist entrepreneurs they interviewed as “informal entrepreneurs”, paralleling the initial thoughts we started with, based on Boyd [7], the results of our study found that informal entrepreneurship was only one of many reasons why African Americans turned to entrepreneurship. Informal entrepreneurship is about avoiding registering a new business with governmental agencies [74]. This distinction between South African and African American entrepreneurs might be related to observations that better financial development as well as better governance increase formal entrepreneurship but decrease informal entrepreneurship, and more so when they are both high [75]. The US being very high in terms of both financial development and governance might be the reason why the African American entrepreneurs we interviewed chose a formal entrepreneurship route, with its long-term worldview, rather than the short-term hunger-prevention route taken by the informal entrepreneurs who du Toit et al. [73] interviewed. Indeed, Ault and Spicer [76] have reported that the conditions created by governance and formal institutional structures play a central role in determining the nature of informal entrepreneurship in each country. Informal entrepreneurship is often the answer to corrupt regulations as well as the consequence of being shut out of alternative employment [77]. Understandably, this is why constructive macro-economic conditions that create strong governance in a country encourage formal entrepreneurship, while low employment rates encourage informal entrepreneurship [78]. The high agency costs of creating a new business in terms of adverse selection and moral hazard costs make entrepreneurs adopt informal entrepreneurship [74].

5. Conclusions

Survivalist entrepreneurship is a concept and a reality that have, perhaps subconsciously, been implemented by African American men due to suboptimal labor force opportunities and conditions as well as lesser academic achievements. While having a unique set of challenges, entrepreneurship can be a viable employment alternative for many African American men. Our research brought to light the entrepreneurial influences on African American men, specifically the notion and purpose of entrepreneurship, career control, and economics, wealth, and legacy. The significance of acknowledging the conditions that have led to the reality of survivalist entrepreneurship is becoming more apparent and can overall help to contribute to the increased economic success of African American men.

Author Contributions

This paper is based on the DBA dissertation of F.J., chaired by D.G., with L.D. as a committee member. Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and analysis by F.J. Validation and supervision by D.G. Writing by all the authors. Project administration by F.J. Supervised by D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Drexel University (protocol #2303009767).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Interview transcripts, excluding identifiers, will be made available by Frederick Jackson upon request, within reason.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Drexel DBA program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Austin, A. The Jobs Crisis for Black Men Is a Lot Worse than You Think; Center for Economic and Policy Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adjeiwaa-Manu, N. Unemployment Data by Race and Ethnicity, 2019. Available online: https://www.globalpolicysolutions.org (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- NCES. Degrees Conferred by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2020. Available online: https://www.nces.ed.gov (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- zippia.com. Entrepreneur Demographics and Statistics in the US, 2022. Available online: https://www.zippia.com/entrepreneur-jobs/demographics/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Henderson, T. Black Families Fall Further Behind on Homeownership, 2022. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Smith, J.T. Ex-Prisoners Face Headwinds as Job Seekers, Even as Openings Abound. 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/06/business/economy/jobs-hiring-after-prison.html#:~:text=An%20estimated%2060%20percent%20of,are%20unemployed%20a%20year%20later (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Boyd, R.L. Survivalist Entrepreneurship among Urban Blacks during the Great Depression: A Test of the Disadvantage Theory of Business Enterprise. Soc. Sci. Q. 2000, 81, 972–984. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, T.; Lee, C.; Carr, N. Do survivalists deserve to be called entrepreneurs? The case of hospitality micro-entrepreneurs in Indonesia. Hosp. Soc. 2023, 13, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choto, P.; Tengeh, R.K.; Iwu, C.G. Daring to survive or to grow? The growth aspirations and challenges of survivalist entrepreneurs in South Africa. Environ. Econ. 2014, 5, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Temkin, B. Informal Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Entrepreneurship or Survivalist Strategy? Some Implications for Public Policy. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2009, 9, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengeh, R.K.; Choto, P. The relevance and challenges of business incubators that support survivalist entrepreneurs. Investig. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2015, 12, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gudeta, A. Survivalist Women Entrepreneur’s Motivation and the Hurdles to Succeed in Ethiopia. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Iwu, C.G.; Opute, A.P. Eradicating poverty and unemployment: Narratives of survivalist entrepreneurs. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2019, 8, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapuranga, M.; Maziriri, E.T.; Rukuni, T.F. A hand to mouth existence: Hurdles emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic for women survivalist entrepreneurs in Johannesburg, South Africa. Afr. J. Gend. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbényiga, D.L.; Ahmedani, B.K. Utilizing social work skills to enhance entrepreneurship training for women: A Ghanaian perspective. J. Community Pract. 2008, 16, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.; Mohlakoana, N.; Knox, A.; Bressers, H. Fuelling women’s empowerment? An exploration of the linkages between gender, entrepreneurship and access to energy in the informal food sector. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 28, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, I. Disadvantaged Minorities in Self-Employment. Comp. Sociol. 1979, 20, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, I.H.; Rosenstein, C.N. Race, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship in Urban America; Aldine de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Light, I.H.; Gold, S.J. Ethnic Economies; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Asoba, S.N.; Patricia, N.M. The profit motive and the enabling environment for growth of survivalist township entrepreneurship: A study at a township in Cape Town. Acad. Entrep. J. 2021, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, T.M. Banking on Black Enterprise: The Potential of Emerging Firms for Revitalizing Urban Economies; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, T.D. The role of black-owned businesses in black community development. In Jobs and Economic Development in Minority Communities; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, T.D. Affirmative Action and Black Entrepreneurship; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dure, E. Black Women Are the Fastest Growing Group of Entrepreneurs. But the Job Isn’t Easy. 2021. Available online: https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/business/business-planning/black-women-are-the-fastest-growing-group-of-entrepreneurs-but-the-job-isnt-easy (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Leppert, R. A Look at Black-Owned Businesses in the U.S. 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/21/a-look-at-black-owned-businesses-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Gibbs, S.R. The Bitter Truth: A Comparative Analysis of Black Male and Black Female Entrepreneurs. J. Dev. Entrep. 2014, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zippia.com. Business Owner Demographics and Statistics in the US, 2022. Available online: https://www.zippia.com/business-owner-jobs/demographics/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Statistics, Bureau of Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/cps/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Kantrowitz, M. Unemployment Rates Are Lower for College Graduates. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/markkantrowitz/2020/12/04/unemployment-rates-are-lower-for-college-graduates/?sh=23f8ce1172f6 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Carnevale, A.P.; Fasules, M.L.; Porter, A.; Landis-Santos, J. African Americans College Majors and Earnings, 2016. Available online: https://cew.georgetown.edu/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Moore, J.S.; Phelps, C. Changing the narrative on African American boys: A systemic approach to school success. Improv. Sch. 2021, 24, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, B. The Effect of Business Coaching and Mentoring on Small-to-Medium Enterprise Performance and Growth; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gravells, J. Mentoring start-up entrepreneurs in the East Midlands–Troubleshooters and Trusted Friends. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. 2006, 4, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Radu Lefebvre, M.; Redien-Collot, R. How to do things with words: The discursive dimension of experiential learning in entrepreneurial mentoring dyads. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 370–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, E.; Audet, J. The role of mentoring in the learning development of the novice entrepreneur. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 8, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, É.; Tremblay, M. Mentoring for entrepreneurs: A boost or a crutch? Long-term effect of mentoring on self-efficacy. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgen, E.; Baron, R.A. Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R. Entrepreneurial learning and mentoring. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2000, 6, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Westhead, P.; Wright, M. Opportunity identification and pursuit: Does an entrepreneur’s human capital matter? Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 30, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wu, S.; Ling, Y. Role of Education and Mentorship in Entrepreneurial Behavior: Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 775227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaique, L.; Pinnington, A.H. Occupational commitment of women working in SET: The impact of coping self-efficacy and mentoring. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022, 32, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, M.; Aboal, D.; Rovira, F. How effective are training and mentorship programs for entrepreneurs at promoting entrepreneurial activity? An impact evaluation. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, E.; Radu-Lefebvre, M.; Mathieu, C. Can less be more? Mentoring functions, learning goal orientation, and novice entrepreneurs’ self-efficacy. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, G.; Jennings, P. Competitive advantage and entrepreneurial power: The dark side of entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2005, 12, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kets de Vries, M.F. The Dark Side of Entrepreneurship; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship: Champaign, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.; Zahra, S. The Other Side of Paradise: Examining the Dark Side of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2011, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A. Learning from business failure: Propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.L. The dark side of the entrepreneur. Long Range Plan. 1991, 24, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T. The True Failure Rate of Small Businesses. 2021. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/starting-a-business/the-true-failure-rate-of-small-businesses/361350 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eesley, C.E.; Hsu, D.H.; Roberts, E.B. The contingent effects of top management teams on venture performance: Aligning founding team composition with innovation strategy and commercialization environment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1798–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, E.P. Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstebro, T.; Thompson, P. Entrepreneurs, jacks of all trades or hobos? Res. Policy 2011, 40, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Cable, D. Network ties, reputation, and the financing of new ventures. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, E. Embeddedness for Control, for Compatibility, or by Constraint? Within-Network Exchange in the Selection of Home Remodelers. 2008. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Embeddedness-for-Control-%2C-for-Compatibility-%2C-or-Zuckerman/181770b129ed5ebfddf7012840beb4875fef011a (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Wang, Y. Bringing the stages back in: Social network ties and start-up firms’ access to venture capital in china. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo Fiorini, P.; Seles, B.M.R.P.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Mariano, E.B.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S. Management theory and big data literature: From a review to a research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Florin, J.; Lubatkin, M.; Schulze, W. A social capital model of high-growth ventures. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.; Wei, K.-K. Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.L. African American Philanthropy; The Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, The Graduate Center: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M.L.; Shapiro, T.M. Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H.; Mann, A.; Meschede, T. Race and Location: The Role Neighborhoods Play in Family Wealth and Well-Being. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 77, 1077–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.H.; Aldrich, H.E.; Keister, L.A. Household income and net worth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurial Dynamics: The Process of Business Creation in Contemporary America; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.S.; Leighton, L.S. Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. Am. Econ. Rev. 1989, 79, 519–535. [Google Scholar]

- Keister, L.A. Wealth in America: Trends in Wealth Inequality; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vedula, S.; Doblinger, C.; Pacheco, D.; York, J.G.; Bacq, S.; Russo, M.; Dean, T.J. Entrepreneurship for the public good: A review, critique, and path forward for social and environmental entrepreneurship research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2022, 16, 391–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Lewis, A.; Cerecedo-Lopez, J.A.; Chapman, K. A racialized view of entrepreneurship: A review and proposal for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2023, 17, 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chauhan, S.; Paul, J.; Jaiswal, M.P. Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toit, M.D.; de Witte, H.; Rothmann, S.; van den Broeck, A. Positive deviant unemployed individuals: Survivalist entrepreneurs in marginalised communities, 2020, unemployment; positive deviance; under-resourced communities; microbusiness entrepreneurs; informal entrepreneurs; South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A. Informality costs: Informal entrepreneurship and innovation in emerging economies. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 329–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A. Formal versus informal entrepreneurship in emerging economies: The roles of governance and the financial sector. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, J.K.; Spicer, A. The formal institutional context of informal entrepreneurship: A cross-national, configurational-based perspective. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Bruton, G.D.; Tihanyi, L.; Ireland, R.D. Research on entrepreneurship in the informal economy: Framing a research agenda. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, E.; van Stel, A.; Storey, D.J. Formal and informal entrepreneurship: A cross-country policy perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).