Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

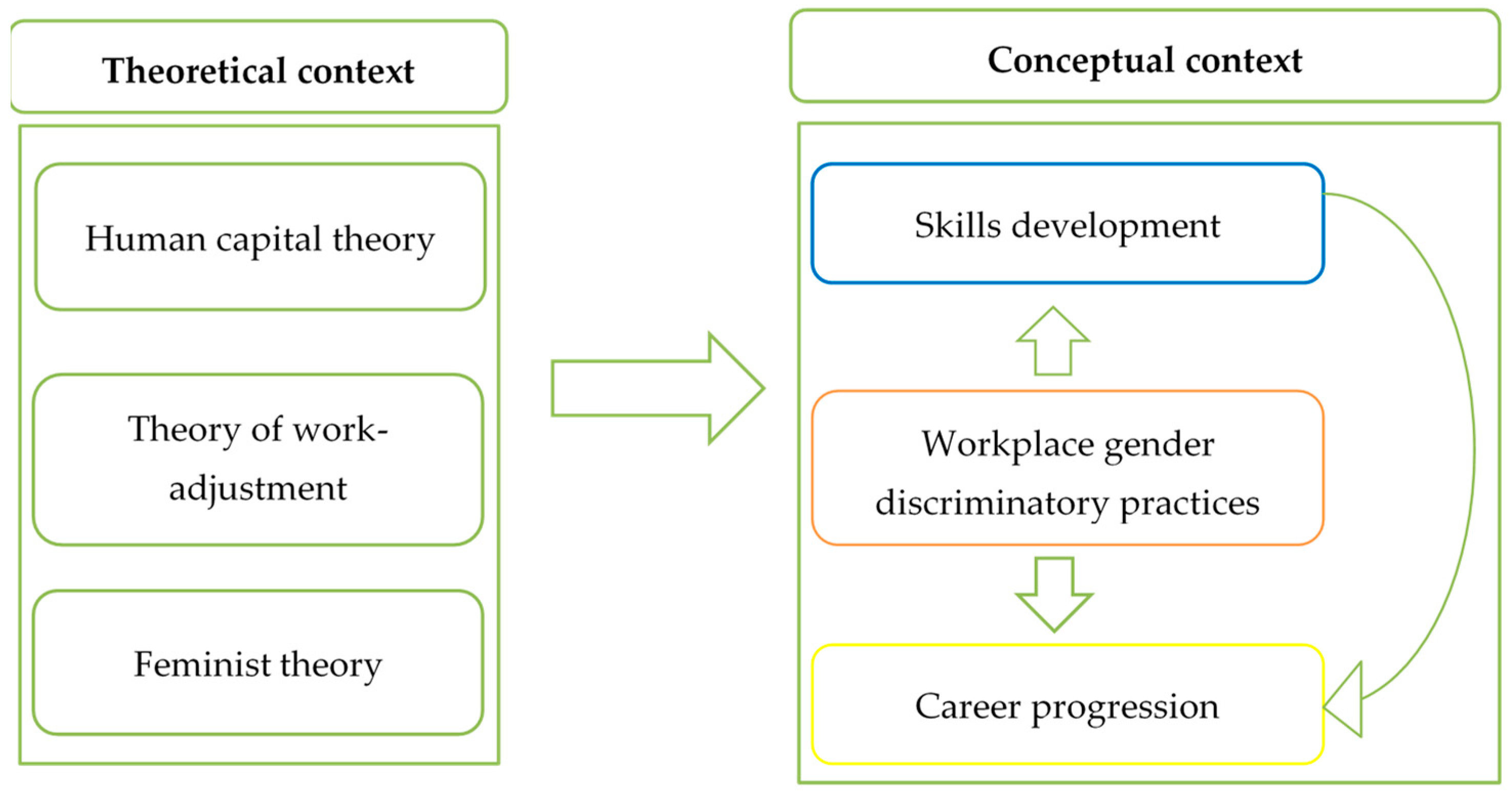

2.1. Theoretical Context

2.2. Conceptual Context

2.2.1. Skills Development

2.2.2. Career Progression

2.2.3. Gender Discriminatory Practices

Gender Stereotypes

Culturally Assigned Roles

Promotion Malpractices

Glass Ceiling

Gender Pay Gap

Sexual Harassment

The Underrepresentation of Women at Senior Levels

Not Addressing Gender Discriminatory Practices

2.3. The Development of Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Population and Sample

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Demographics

4.1.2. Central Tendency

4.1.3. Normality Test

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement/Research Model

4.2.1. Confirmatory Factors Analysis

4.2.2. Structural Model Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical Contribution and Practical Implications

7. Research Limitations and Recommendations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic Variable | Frequency | Percentage (n = 412) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Below 21 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 21–25 | 75 | 18.2 | |

| 26–30 | 150 | 36.4 | |

| 31–35 | 87 | 21.1 | |

| 36–40 | 63 | 15.3 | |

| 41–45 | 18 | 4.4 | |

| 46–50 | 12 | 2.9 | |

| 51–55 | 4 | 1.0 | |

| 56–60 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 224 | 54.4 |

| Married | 147 | 35.7 | |

| Widowed | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Divorced/separated | 15 | 3.6 | |

| Partnership/Cohabitation | 19 | 4.6 | |

| Race | African | 347 | 84.2 |

| Colored | 41 | 10 | |

| Indian/Asian | 6 | 1.5 | |

| White | 17 | 4.1 | |

| Others | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Job level | Semi-skilled worker | 91 | 22.1 |

| Skilled worker/Junior manager | 213 | 51.7 | |

| Manager | 50 | 12.1 | |

| Middle manager | 25 | 6.1 | |

| Senior manager | 23 | 5.6 | |

| Top manager/Executive | 10 | 2.4 | |

| Qualification level | No matric | 4 | 1 |

| Matric | 53 | 12.9 | |

| Certificate or diploma | 120 | 29.1 | |

| 1st degree | 141 | 34.2 | |

| Honors/Postgraduate | 69 | 16.7 | |

| Masters and above | 25 | 6.1 | |

| Tenure at the company | 1–5 years | 253 | 61.4 |

| 6–10 years | 126 | 30.6 | |

| 11–20 years | 24 | 5.8 | |

| 21 and above | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Number of employees in your company | Less than 10 | 48 | 11.7 |

| 11–50 employees | 182 | 44.2 | |

| 51–200 employees | 80 | 19.4 | |

| Above 200 employees | 48 | 11.7 | |

| I don’t know | 54 | 13.1 | |

Appendix B

| Item Codes | Item | Overall Disagree (Strongly Disagree and Disagree) | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Overall Agree (Strongly Agree and Agree) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Development (Mean = 2.90, Std. Dev = 1.536) | ||||||

| SKILDEV1 | At work, I engage in programs/projects that develop my skills. | 51.7% | 3.9% | 44.4% | 2.91 | 1.577 |

| SKILDEV2 | The skills development opportunities offered by my company are aligned to my career plans/needs. | 50.5% | 6.8% | 42.7% | 2.89 | 1.527 |

| SKILDEV3 | My skills have progressively improved over time. | 50.5% | 5.6% | 44% | 2.93 | 1.561 |

| SKILDEV4 | I continuously learn new things in my work. | 52.9% | 3.2% | 43.9% | 2.87 | 1.609 |

| Career progression (Mean = 2.92, Std. Dev = 1.258) | ||||||

| CARPROG1 | I got promoted into a higher position within my organization. | 47.6% | 19.9% | 32.6% | 2.83 | 1.305 |

| CARPROG2 | My responsibilities at work have increased over time. | 42.5% | 16.7% | 40.7% | 2.99 | 1.288 |

| CARPROG3 | My authority in my company has increased over time. | 45.0% | 18.4% | 35.9% | 2.91 | 1.309 |

| CARPROG4 | I am satisfied with my career progress at work. | 38.1% | 14.6% | 40.7% | 2.94 | 1.434 |

| CARPROG5 | My Job title has changed favorably over time. | 45.9% | 15.0% | 39.0% | 2.93 | 1.401 |

| Gender discriminatory practices (Mean = 2.50, Std. Dev = 1.049) | ||||||

| GENDESC1 | There are preconceptions about women’s attributes, characteristics or professional abilities in my organization. | 48.8% | 23.8% | 27.5% | 2.73 | 1.240 |

| GENDESC2 | In my workplace, women are treated based on their culturally assigned roles. | 52% | 25.5% | 22.5% | 2.57 | 1.178 |

| GENDESC3 | In my organization women are subjected to unfavorable perceptions when assessed for promotion. | 55.4% | 22.1% | 22.5% | 2.54 | 1.188 |

| GENDESC4 | I feel that women’s careers are stuck at lower and middle management levels in my organization. | 55.3% | 20.9% | 23.8% | 2.52 | 1.237 |

| GENDESC5 | In my company, women earn lower salaries than men for the same job done. | 58.7% | 22.8% | 18.4% | 2.39 | 1.182 |

| GENDESC6 | Cases of sexual harassment were reported by women in my workplace. | 59.4% | 21.8% | 18.7% | 2.40 | 1.185 |

| GENDESC7 | Women are unfairly represented (less than 50%) at senior levels in the organization. | 59.5% | 20.1% | 20.4% | 2.42 | 1.194 |

| GENDESC8 | When reported, my organization puts in little or no effort to address discriminatory gender practices. | 59% | 22.1% | 18.9% | 2.41 | 1.210 |

References

- Jaga, A.; Arabandi, B.; Bagraim, J.; Mdlongwa, S. Doing the ‘gender dance’: Black women professionals negotiating gender, race, work and family in post-apartheid South Africa. Community Work. Fam. 2016, 21, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komalasari, Y.; Supartha, W.G.; Rahyuda, A.G.; Dewi, G.A.M. Fear of Success on Women’s Career Development: A Research and Future Agenda. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, A. Pregnancy is here to stay—Or is it? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2016; Bosh, A., Ed.; SABPP: Parktown, South Africa, 2016; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moalusi, K.P.; Jones, C.M. Women’s prospects for career advancement: Narratives of women in core mining positions in a South African mining organisation. SA J. Indstrial Psychol. SA Tydskr. Bedryfsielkunde 2019, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A. Rethinking women’s workplace outcomes: Structural inequality. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2017; Bosh, A., Ed.; SABPP: Parktown, South Africa, 2017; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jáuregui, K.; Olivos, M. The career advancement challenge faced by female executives in Peruvian organisations. BAR Braz. Adm. Rev. 2018, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, A.M.; Mikyong, M.K. Successful Latina scientists and engineers: Their lived mentoring experiences and career development. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.; Richardsen, A. Women in Management Worldwide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Matotoka, M.D.; Odeku, K.O. Mainstreaming Black Women into Managerial Positions in the South African Corporate Sector in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Potchefstroom Electron. Law J. 2021, 24, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. The Gender Gap in Employment: What’s Holding Women Back? 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/infostories/en-GB/Stories/Employment/barriers-women#intro (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- World Economic Forum. Insight Report: The Global Gender Gap Report 2020. 2020. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Gipson, A.N.; Pfaff, D.L.; Mendelsohn, D.B.; Catenacci, L.T.; Burke, W.W. Women and Leadership: Selection, Development, Leadership Style, and Performance. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 32–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mythili, N. Quest for Success: Ladder of School Leadership of Women in India. Soc. Chang. 2019, 49, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Women in the Workplace 2019. 2019. Available online: https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2019.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Afande, F.O. Factors affecting women career advancement in the banking industry in Kenya (a case of Kenya Commercial Bank branches in Nairobi County, Kenya). J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2015, 9, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Biwa, V. African Feminisms and Co-constructing a Collaborative Future with Men: Namibian Women in Mining’s Discourses. Manag. Commun. Q. 2021, 35, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawuni, J.J.; Masengu, T. Judicial Service Commissions and the appointment of women to higher courts in Nigeria and Zambia. In Research Handbook on Law and Courts (Research Handbooks in Law and Politics Series); Sterett, S.M., Walker, L.D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. “More power to your great self”: Nigerian women’s activism and the pan African transnationalist construction of black feminism. Phylon 2016, 53, 54–78. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics South Africa. Statistical Release P0211-Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 2: 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=15668 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Fitong Ketchiwou, G.; Naong, M.N.; Van Der Walt, F.; Dzansi, L.W. Investigating the relationship between selected organisational factors and women’s skills development aspirations and career progression: A South African case study. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. SA Tydskr. Menslikehulpbronbestuur 2022, 20, a1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry. Industrial Policy Action Plan: Economic Sectors, Employment and Infrastructure Development Cluster 2018/19–2020/21. 2018. Available online: http://www.thedtic.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/publication-IPAP1.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Mathur-Helm, B. Lack of HR management interventions specifically directed at women blue-collar workers. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2018; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2018; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T. How to increase women’s representation in the construction sector: Evidence from a UK project. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2018; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2018; pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities. Beijing +25 South Africa’s Report on the Progress Made on the Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action 2014–2019. 2019. Available online: http://www.women.gov.za/images/Final-National-Beijing-25-Report-2014-2019--Abrideged-pdf (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Gouws, A. The state of women’s politics in South Africa, 25 years after democratic transition. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2019; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Weltevredenpark, South Africa, 2019; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Moleko, N. Do we have the tracking tools to monitor the National Gender Machinery? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2019; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Weltevredenpark, South Africa, 2019; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, C.; Schlechter, A. To (queen) bee or not to bee? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2019; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2019; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, L. Rise of the machines: Friend or foe for female blue-collar workers? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lwesi, D. Neo-liberalism, gender, and South African working women. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2019; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Weltevredenpark, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, D. Barriers to career advancement of women in mining: A qualitative analysis. South Afr. J. Labour Relat. 2017, 41, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Naudé, P. Women in the workplace: En route to fairness? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2017; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2017; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, H.; Naidoo, P.; Malope, N. Labour law and the trial and tribulations of women blue-collar workers. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2018; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Rosebank, South Africa, 2018; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, E.; Naidoo, L. An investigation into the challenges faced by women when progressing into leadership positions at a manufacturing organisation in South Africa. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen, R.M.; Tonelli, L.; Mayer, C.H. Subjective experiences of employment equity in South African organisations. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. SA Tydskr. Menslikehulpbronbestuur 2019, 17, 1–12.a1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe-Walsh, L.; Turnbull, S.L. Barriers to women leaders in academia: Tales from science and technology. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S. An Attorney’s Work to Make South Africa’s Promise of Equality a Reality. ONE. 2019. Available online: https://www.one.org/international/blog/attorney-south-africa-equality/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIsJGVv7CP6AIV1eF3Ch0M_AaBEAAYASAAEgKMFfD_BwE (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Lewis, S.; Beauregard, T.A. The meanings of work-life balance: A cultural perspective. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Global Work-Family Interface; Johnson, R., Shen, W., Shockley, K.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 720–732. [Google Scholar]

- Rohman, J.; Onyeagoro, C.; Bush, M.C. How You Promote People Can Make or Break Company Culture. Harvard Business Review. 2 January 2018. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/01/how-you-promote-people-can-make-or-break-company-culture (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Zenger, J.; Folkman, J. Research: Women Score Higher than Men in Most Leadership Skills. Harvard Business Review. 25 June 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/06/research-women-score-higher-than-men-in-most-leadership-skills?utm_campaign=hbr&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR1GeWdPmFba_V6mrSeSEQshgPLciFWycM2u9OZFhgeT7BCTg44Mx6ot-Eg (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kondo, N. Organizational justice, psychological distress, and stress-related behaviors by occupational class in female Japanese employees. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howson, C.B.K.; Coate, K.; de St Croix, T. Mid-Career academic women and the prestige economy. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 33, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, E.; Julaeha, D.S. Employee development at the manpower and transmigration office of Sumedang regency. J. Adm. Publik (Public Adm. J.) 2020, 10, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.A.; Martin, A.E.; Huda, I.; Matz, S.C. Hiring women into senior leadership positions is associated with a reduction in gender stereotypes in organizational language. Psychol. Cogn. Sci. 2022, 119, e2026443119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwood, C.; Surie, A.; Haskins, L.; Luthuli, S.; Hinton RChowdhury, A.; Rollins, N. Attitudes and perceptions about breastfeeding among female and male informal workers in India and South Africa. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medupe, S. South Africa Ranked the Top Global Business Services Sector Location for 2021 and Sector Adds New Jobs to the Economy. BPESA News. 2021. Available online: https://www.bpesa.org.za/news/357-south-africa-ranked-the-top-global-business-services-sector-location-for-2021-and-sector-adds-new-jobs-to-the-economy.htm (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Galal, S. Number of Female Employees in South Africa in Q4 2021 by Industry. Statista. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1129825/number-of-female-employees-in-south-africa-by-industry/#:~:text=Number%20of%20female%20employees%20in%20South%20Africa%202021%2C%20by%20industry&text=In%20the%20fourth%20quarter%20of,community%20and%20social%20services%20industry (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Butler, G.; Rogerson, C.M. Inclusive local tourism development in South Africa: Evidence from Dullstroom. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 246–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnachef, T.H.; Alhajjar, A.A. Effect of human capital on organizational performance: A literature review. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 6, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Hideg, I.; Krstic, A.; Trau, R.N.C.; Zarina, T. The unintended consequences of maternity leaves: How agency interventions mitigate the negative effects of longer legislated maternity leaves. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.I.; Abdul-Majid, A.H.; Musibau, H.O. Employee learning theories and their organizational applications. Acad. J. Econ. Stud. 2017, 3, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachová, K.; Raišienė, A.G. Changes in approach to employee development in organizations on a regional scale. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W. 8 Ways to Successfully Develop Employees Year-Round. Forbes. 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamcraig/2018/08/21/8-ways-to-successfully-develop-employees-year-round/#1f78c04f5c41 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Van Ruysseveldt, J.; van Wiggen-Valkenburg, T.; van Dam, K. The self-initiated work adjustment for learning scale: Development and validation. J. Manag. Psychol. 2021, 36, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauser, D.R.; Greco, C.E.; Koscuilek, J.F.; Shen, S.; Strausser, D.G.; Phillips, B.N. A tool to measure work adjustment in the post-pandemic economy: The Illinois work adjustment scale. J. Vocat. Rehabilitation 2021, 54, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Research Methodology: A Step by Step Guide for Beginners, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhow, C.; Lewin, C. Social media and education: Reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learn. Media Technol. 2016, 41, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vnoučková, L.; Urbancová, H.; Smolová, H. Approaches to employee development in Czech organisations. J. Efic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanya, J.J.; Cinjel, N.D. Employee training and employee development in an Organization: Explaining the difference for the avoidance of research pitfalls. In Public Administration: Theory and Practice in Nigeria; Omenka, J.I., Cinjel, N.D., Achanya, J.J., Eds.; Chananprints: Lagos, Nigeria, 2022; pp. 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Genchev, S.E.; Willis, G.; Griffis, B. Returns management employee development: Antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 1016–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Bartol, K.M.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Li, C. Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team knowledge sharing: Influences of dual-focused transformational leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 38, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes India. Removing Workplace Biases with ‘Behavioural Design’. 2017. Available online: http://www.forbesindia.com/article/rotman/removing-workplace-biases-with-behavioural-design/48945/1 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Adhikari, H.P. Employee development and career system for enhancing professionalism in the public sector of Nepal. South Asian J. Policy Gov. 2020, 44, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Shao, Y. The Impact of Training on Turnover Intention: The Role of Growth Need Strength among Vietnamese Female Employees. South East Asian J. Manag. 2019, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapuano, V. Toward sustainable careers: Literature review. Contemp. Res. Organ. Manag. Adm. 2020, 8, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz, M.; Bolton, M.; Emslie, K. Is Menopause a Taboo in Your Organization? Harvard Business Review. 4 February 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/amp/2020/02/is-menopause-a-taboo-in-your-organization (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Osibanjo, A.O.; Oyewunmi, A.E.; Ojo, S.I. Career development as a determinant of organisation growth: Modelling the relationship between these constructs in the Nigerian banking industry. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Prossack, A. 5 Things You Can Do to Advance Your Career. Forbes. 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashiraprossack1/2018/08/29/a-guide-to-advancing-your-career/#3869e4133cfa (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Vasel, K. How Long Should You Stay at a Job if You Aren’t Being Promoted. CNN Business. 2019. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/06/03/success/how-long-promoted-stay-job/index.html (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Sobczak, A. The queen bee syndrome. The paradox of women discrimination on the labour market. J. Gend. Power 2018, 9, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, J.; Coplen, C.; Malloy, R. Boston Women Leaders: How We Got Here. Spencer Stuart. 2019. Available online: https://www.spencerstuart.com/research-and-insight/women-leaders-how-we-got-here (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Padilla, L.M. Presumptions of Incompetence, Gender Sidelining, and Women Law Deans. In Presumed Incompetent II: Race, Class, Power, and Resistance of Women in Academia; Niemann, Y.F., Muhs, G.G.Y., González, C.G., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ensour, W.; Al Maaitah, H.; Kharabsheh, R. Barriers to Arab female academics’ career development: Legislation, HR policies and socio-cultural variables. Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 1058–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébaud, S. Status beliefs and the spirit of capitalism: Accounting for gender biases in entrepreneurship and innovation. Soc. Forces 2015, 94, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shirmohammadi, M. Women Leaders in China: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2016, 18, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Jantan AH Hashim, H.B.; Chong, C.W.; Abdullah, M.M. Factors influencing female progression in leadership positions in the ready- made garment (RMG) industry in Bangladesh. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, S.; Rehman, M.; Muqadas, F.; Rehman, S. Women leadership and its mentoring role towards career development. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2017, 19, 649–667. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Giuliano, P.; Nunn, N. On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough. Q. J. Econ. 2013, 128, 469–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, C. Glass ceiling in Korean Civil Service: Analyzing barriers to women’s career advancement in the Korean Government. J. Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. Addressing gender quotas in South Africa: Women empowerment and gender equality legislation. J. Deakin Law Rev. 2015, 20, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A. Reasons for gender pay gap—What HR practitioners should know. In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2015; Bosch, A., Ed.; SABPP: Parktown, South Africa, 2015; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Naong, M.N. The moderating effect of skills development transfer on organizational commitment—A case-study of Free State TVET colleges. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2016, 14, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Research Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Christensen, L. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Science Research, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlall, I. Applied Structural Equation Modelling for Researchers and Practitioners: Using R and Stata for Behavioural Research; Emerald Group Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Assessing Normal Distribution (2) Using Skewness and Kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2015, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newsbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Nunan, D.; Birks, D.F. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS, 4th ed.; Open University Press/McGraw-Hill: Maidenhead, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, L.; Recalde, M.P.; Vesterlund, L. Why Women Volunteer for Tasks That Don’t Lead to Promotions. Harvard Business Review. 16 July 2018. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/07/why-women-volunteer-for-tasks-that-dont-lead-to-promotions (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Manuti, A.; Pastore, S.; Scardigno, A.F.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Morciano, D. Formal and informal learning in the workplace: A research review. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carucci, R. When Companies Should Invest in Training Their Employees—And When They Shouldn’t. Harvard Business Review. 29 October 2018. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/10/when-companies-should-invest-in-training-their-employees-and-when-they-shouldnt (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Wirth-Dominicé, L. Women in Business and Management Gaining Momentum. International Labour Organisation. 2015. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/dgreports/dcomm/publ/documents/publication/wcms_334882.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Leuze, K.; Strauß, S. Why do occupations dominated by women pay less? How ‘female-typical’ work tasks and working-time arrangements affect the gender wage gap among higher education graduates. Work. Employ. Soc. 2016, 30, 802–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|

| Skills development of women | 0.145 | −1.628 |

| Career progression of women | 0.194 | −1.261 |

| Workplace gender discrimination | 0.665 | −0.332 |

| Constructs | Item Codes * | Factor Loadings | p-Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | Final Number of Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill Development | SKILDEV1 | 0.968 | *** | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.945 | 4 |

| SKILDEV2 | 0.969 | *** | |||||

| SKILDEV3 | 0.980 | *** | |||||

| SKILDEV4 | 0.972 | *** | |||||

| Career Progression | CARPROG1 | 0.830 | *** | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.748 | 5 |

| CARPROG2 | 0.938 | *** | |||||

| CARPROG3 | 0.933 | *** | |||||

| CARPROG4 | 0.943 | *** | |||||

| CARPROG5 | 0.935 | *** | |||||

| Gender Discriminatory Practices | GENDESC2 | 0.793 | *** | 0.957 | 0.963 | 0.841 | 7 |

| GENDESC3 | 0.822 | *** | |||||

| GENDESC4 | 0.857 | *** | |||||

| GENDESC5 | 0.883 | *** | |||||

| GENDESC6 | 0.905 | *** | |||||

| GENDESC7 | 0.888 | *** | |||||

| GENDESC8 | 0.898 | *** |

| Skill Development | Gender Discriminatory Practices | Career Progression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill Development | 0.972 | ||

| Gender Discriminatory Practices | 0.449 | 0.865 | |

| Career Progression | 0.914 | 0.421 | 0.917 |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | β Values | p-Values | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Development of Women | Workplace Gender Discriminatory Practices | 0.393 | 0.002 | H1 is accepted |

| Career Progression of Women | Workplace Gender Discriminatory Practices | 0.062 | 0.624 | H2 is rejected |

| Career Progression of Women | Skills Development of Women | 0.91 | 0.000 | H3 is accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fitong Ketchiwou, G.; Dzansi, L.W. Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work. Businesses 2023, 3, 347-367. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses3020022

Fitong Ketchiwou G, Dzansi LW. Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work. Businesses. 2023; 3(2):347-367. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses3020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleFitong Ketchiwou, Gaelle, and Lineo Winifred Dzansi. 2023. "Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work" Businesses 3, no. 2: 347-367. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses3020022

APA StyleFitong Ketchiwou, G., & Dzansi, L. W. (2023). Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work. Businesses, 3(2), 347-367. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses3020022