Barriers to the Effective Integration of Developed ICT for SMEs in Rural NIGERIA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

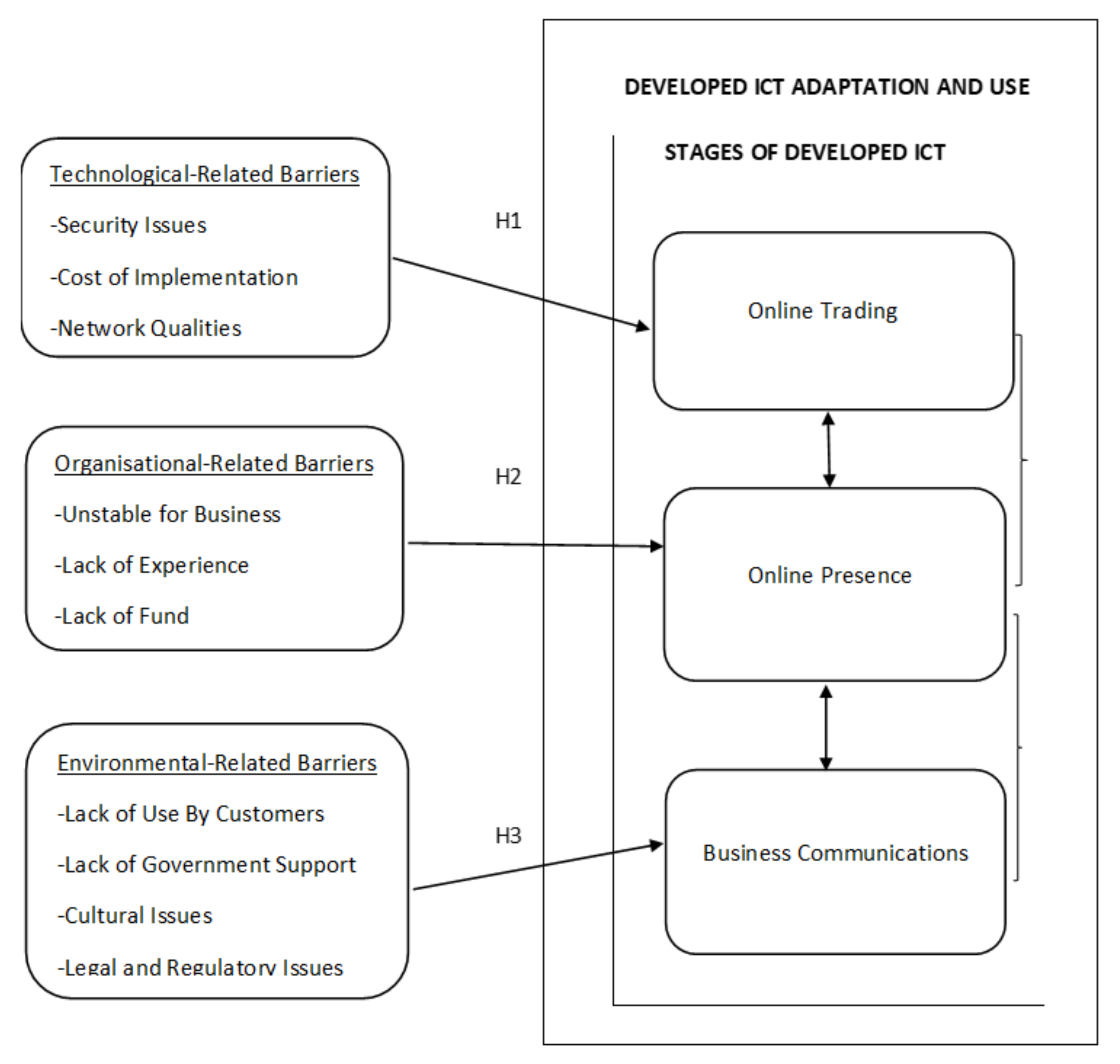

2.1. Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) Framework

2.2. Stages-of-Growth (SOG) Model

2.3. Rationale for Using TOE Framework and the Stage-of-Growth (SOG) Model

2.4. Barriers Affecting the Integration of Developed ICTs

2.4.1. Technology-Related Barriers

2.4.2. Organisational Barriers

2.4.3. Environmental Barriers

3. Methodology

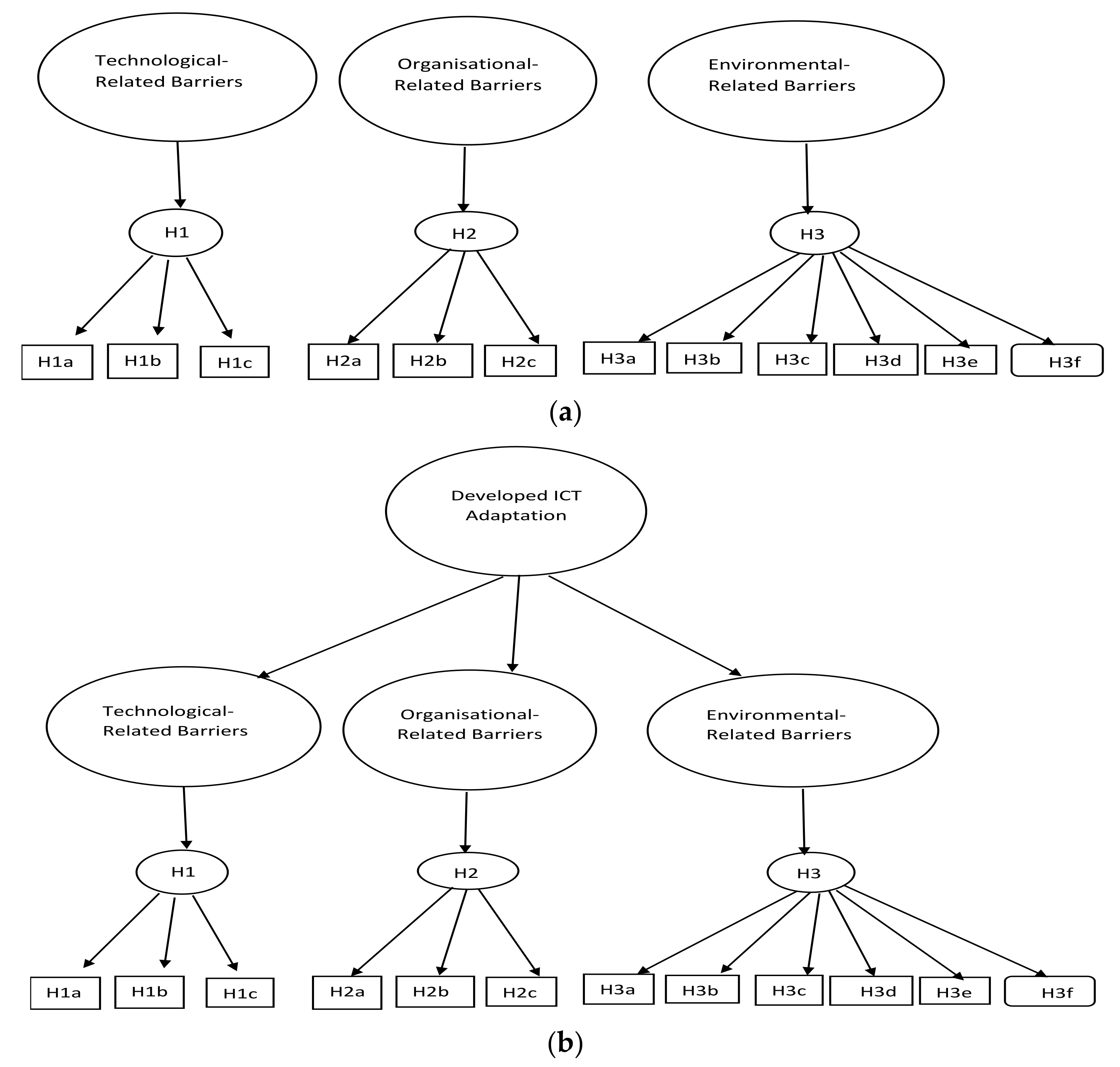

3.1. Hierarchical Reflective Model

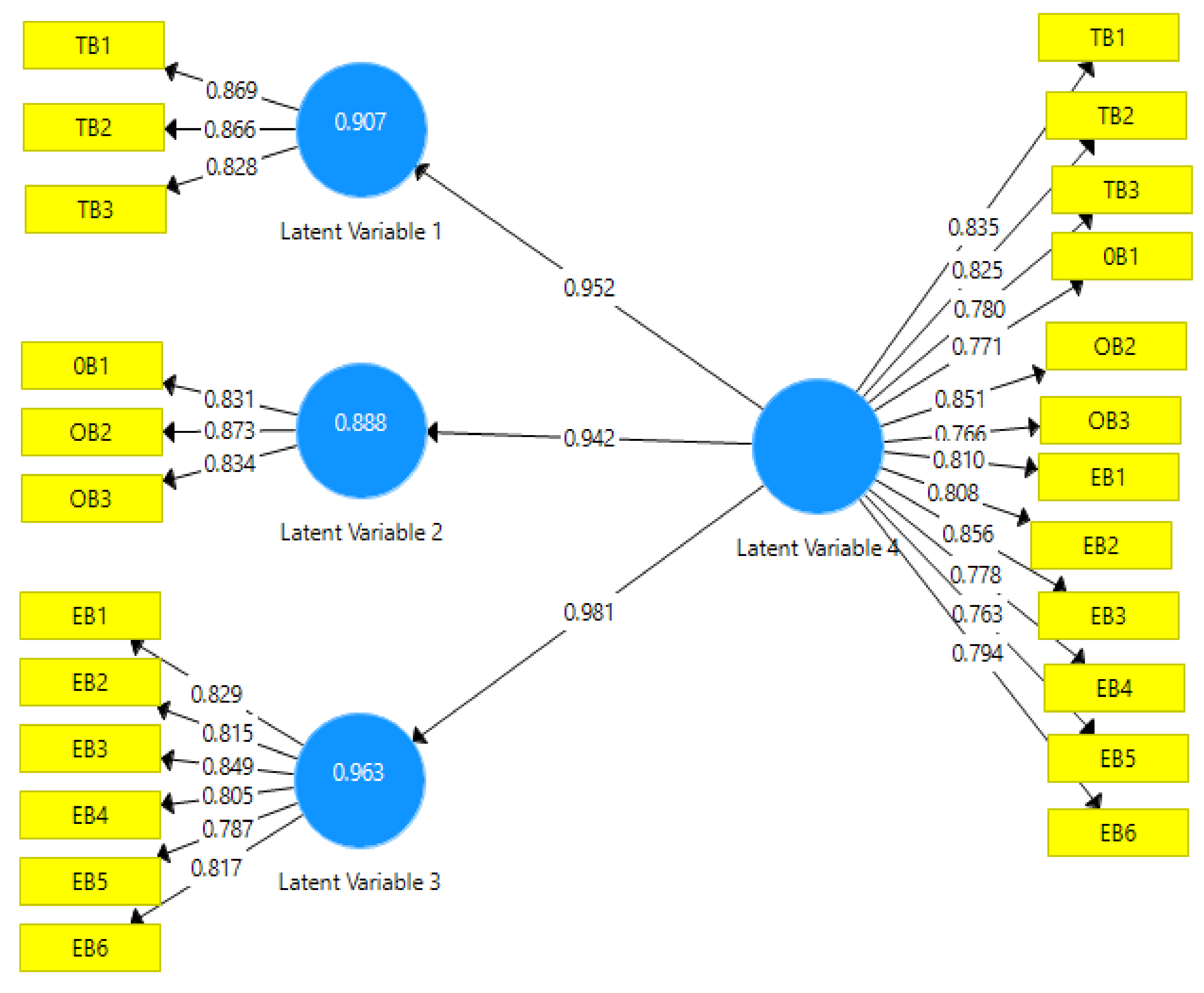

3.2. Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling Results

3.2.1. Scrutinising the Measurement Model

3.2.2. Evaluation of Higher-Order Model

3.2.3. Assessment of Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Themes and Hypothesis Testing

4.2. Technological-Related Barriers

4.3. Organisational-Related Barriers

4.4. The Environmental-Related Barriers

5. Conclusions

6. Theoretical Implications

6.1. Practical Implications

6.1.1. Implications for Rural SMEs

6.1.2. Implications for Educational Institutions and Training Communities

6.1.3. Implications for the Government

6.2. Limitations of the Study

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henderson, D. Demand-side broadband policy in the context of digital transformation: An examination of SME digital advisory policies in Wales. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheer, M.F.; Raoof, R.; Jabeen, S.; Hassan, S.G. Exploring the Nexus Among the Business Coping Strategy: Entrepreneurial Orientation and Crisis Readiness–A Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Pakistani SMEs. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship, Innovation, Sustainability, and ICTs in the Post-COVID-19 Era; IGI Global: Hershey, Pennsylvania, 2021; pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, K.K.; Tsai, C.-W.; Agrawal, A.K. Impact of peer influence and government support for successful adoption of technology for vocational education: A quantitative study using PLS-SEM technique. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 2041–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.C.; Chinedu-Eze, V.C.; Nwanji, T.; Bello, A.O. Examining mobile marketing technology adoption from an evolutionary process perspective: The study of the UK service SMEs. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2021, 37, 151–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, W.B. The role of ICT in knowledge management processes: A Review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Comput. 2018, 8, 16373–16380. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, N.A.H.A. ICT usage performance of small and medium enterprises and their exporting activity in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, M.; Linderoth, H.C.J. The influence of contextual elements, actors frame of references and technology on the adoption and use of ICT in construction projects: A Swedish case study. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.E. Examining the factors that influence ICT adoption in SMEs: A research preliminary findings. Int. J. Technol. Diffus. 2015, 6, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kannabiran, G.; Dharmalingam, P. Enablers and inhibitors of advance information technologies adoption by SMEs: An empirical study of auto ancillaries in India. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2012, 25, 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. State of growth barriers of SMEs in Pakistan: A review based on empirical and theoretical models. NICE Res. J. 2018, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndemo, B. The role of mobile technologies and inclusive innovation policies in SME development in Sub Saharan Africa. In A Research Agenda for Entrepreneurship Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, H.A.; Schorch, M.; Hassan, S.S.; Skudelny, S.; Grinko, M.; Pipek, V. From Technology Adoption to Organizational Resilience: A Current Research Perspective; University of Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Awa, H.O.; Nwibere, B.M.; Inyang, B.J. The uptake of electronic commerce by SMEs: A mete theoretical framework expanding the determining constructs of TAM and TOE framework. J. Glob. Bus. Technol. 2015, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Agbor, D.K. Drivers and challenges of ICT adoption by SMEs in Accra metropolis, Ghana. J. Technol. Res. 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Igwe, S.R.; Ebenuwa, A.; Idenedo, O.W. Technology adoption and sales performance of manufacturing small and medium enterprises in port harcourt. J. Mark. 2020, 5, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, R.; Ali, M.A.; Mahfuz, M.A. An Empirical Investigation on the Adoption of E-Commerce in Bangladesh. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.C.; Chinedu-Eze, V.C.A.; Okike, C.K.; Bello, A.O. Critical factors influencing the adoption of digital marketing devices by service-oriented micro-businesses in Nigeria: A thematic analysis approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S.; Nzei, J. Evaluation of mobile services and substantial adoption factors with Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Telecommun. Policy 2013, 37, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, D. Regional ICT access and entrepreneurship: Evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, M. Digitalization, Internationalization and Scaling of Online SMEs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF Report. The Current Economic Status of Nigeria for the Year (2019). Available online: http://www.imf.org.external/country/NGA/ (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Adane, M. Cloud computing adoption: Strategies for Sub-Saharan Africa SMEs for enhancing competitiveness. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, N.G.M.N. 5G White Paper. Next Generation Mobile Networks, White Paper; NGMN: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R. E-Communication Adoption and its Impact on SMEs: A Case of Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Scotland, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hack-Polay, D.; Igwe, P.A.; O Madichie, N. The role of institutional and family embeddedness in the failure of Sub-Saharan African migrant family businesses. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 21, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Arias-Aranda, D.; Benitez-Amado, J. Adoption of e-commerce applications in SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 1238–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Hurd, F. Exploring the Impact of Digital Platforms on SME Internationalization: New Zealand SMEs Use of the Alibaba Platform for Chinese Market Entry. J. Asia-Pacific Bus. 2018, 19, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkenhoff, K.; Wilkens, U.; Zheng, M.; Süße, T.; Kuhlenkötter, B.; Ming, X. Key challenges of digital business ecosystem development and how to cope with them. Procedia Cirp 2018, 73, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU. Measuring the Information Society Report; International Communications Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agwu, M.E. Analysis of the impact of strategic management on the business performance of SMEs in Nigeria. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mendy, J.; Odunukan, K.; Rahman, M. Place and policy barriers of rural Nigeria’s small and medium enterprises’ internationalization. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 63, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Okundaye, K.; Fan, S.K.; Dwyer, R.J. Impact of information and communication technology in Nigerian small-to medium-sized enterprises. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci. 2019, 24, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, R.C.; Kartiwi, M. Perception of barriers to e-commerce adoption in SMEs in a developed and developing country: A comparison between Australia and Indonesia. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2010, 8, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.; Fleischer, M. The Process of Technology Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.F.; Nolan, R.L. Managing the Four Stages of EDP Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1974, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Reggi, L.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Addressing territorial digital divides through ICT strategies: Are investment decisions consistent with local needs? Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101562. [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostritsova, V. ICT and Big Data Adoption in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Regions of Alto Trás-os-Montes, Castela e Leão and Krasnodar Region. Ph.D. Thesis, Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão de Bragança, Bragança, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Orser, B.; Riding, A.; Li, Y. Technology adoption and gender-inclusive entrepreneurship education and training. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, K.; Aramburu, N.; Lorenzo, O.J. Promoting digitally enabled growth in SMEs: A framework proposal. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 33, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. September. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. (Eds.); Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dassisti, M.; Giovannini, A.; Merla, P.; Chimienti, M.; Panetto, H. An approach to support I4.0 adoption in SMEs: A core-metamodel and applications. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; van Dinther, C.; Kiefer, D. Machine Learning in SME: An Empirical Study on Enablers and Success Factors; AWS: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cieciora, M.; Bołkunow, W.; Pietrzak, P.; Gago, P. Key criteria of ERP/CRM systems selection in SMEs in Poland. Online J. Appl. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 7, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, T.; Deng, H. Critical determinants for mobile commerce adoption in Vietnamese SMEs: A preliminary study. In Proceedings of the 29th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Sydney, Australia, 3–5 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jabri, I.M.; Sohail, M.S. Mobile banking adoption: Application of diffusion of innovation theory. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, M.H.D.; Perera, M.P.S. Relationship between the antecedents of ICT Adoption and the Business Performance of SMEs in the Colombo District, Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan J. Entrep. 2020, 2, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Suprabha, K.R.; Geetha, V. ICT usage and SME Growth: An Analysis of Small and Medium Enterprises in Coastal Karnataka. Nitte Manag. Rev. 2018, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, S.; Canhoto, A.; Molinillo, S.; Pera, R.; Budhathoki, T. Conceptualising a digital orientation: Antecedents of supporting SME performance in the digital economy. J. Strat. Mark. 2018, 26, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusly, F.H.; Taliba, Y.Y.A.; Abd Mutaliba, H.; Hussina, M.R.A. Developing a Digital Adaptation Model for Malaysian Manufacturing SMEs. In Proceedings of the 4th UUM International Qualitative Research Conference (QRC 2020), Virtual, 1–3 December 2020; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shee, H.; Miah, S.J.; Fairfield, L.; Pujawan, N. The impact of cloud-enabled process integration on supply chain performance and firm sustainability: The moderating role of top management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Martins, M.F. Literature review of information technology adoption models at firm level. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2011, 14, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, S.M.; Bahadori, R.; Jafarnejad, H. The smart SME technology readiness assessment methodology in the context of industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 1037–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Martínez, J.; Navío-Marco, J.; Rodrigo-Moya, B. Analysis of the adoption of customer facing InStore technologies in retail SMEs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, E.; Mishra, A.J. Understanding the gendered nature of developing country MSMEs’ access, adoption and use of information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D). Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2020, 12, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.J.; Tran, Q.D. Study on e-commerce adoption in SMEs under the institutional perspective: The case of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. E-Adopt. 2018, 10, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, L.M. Use of the Internet as a Business Tool by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (Smes): A Descriptive Study of Small Minnesota-Based Manufacturers’ Internet Usage; Capella University: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Calderia, M.M.; Ward, J.M. Using resource-based theory to Interpret the successful adoption and use of information systems and technology in manufacturing small and medium sized enterprises. Global co-operation in the New Millennium. In In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Information Systems, Bled, Slovenia, 27–29 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S. An examination of e-market adoption in Australian SMEs. Small Enterp. Res. 2020, 27, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, S.; Cave, J. Information Communication Technology in New Zealand SMEs; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 1, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.-P.; Yeh, H.; Ma, R.-L. A study of the CSFs of an e-cluster platform adoption for microenterprises. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 19, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B.; Raja, S.; Kayumova, M. Digital innovation in SMEs: A systematic review, synthesis and research agenda. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2021, 28, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Hassan, S.; Gusau, A.L. Factors Influencing Acceptance and Use of ICT Innovations by Agribusinesses. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2018, 26, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalinger, D.; Grivas, S.G.; de la Harpe, A. TEA-A Technology Evaluation and Adoption Influence Framework for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. In International Conference on Business Information Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z. The impacts of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and E-commerce on bilateral trade flows. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2018, 15, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.-W.; Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, J.-J.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Time to seize the digital evolution: Adoption of blockchain in operations and supply chain management among Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 101–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, E.; Ruiz, L.; Valencia, A.; Picón, E. Electronic Commerce: Factors Involved in its Adoption from a Bibliometric Analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D. The impact of entrepreneurs’ environmental analysis strategy on organizational performance. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahnil, M.I.; Marzuki, K.M.; Langgat, J.; Fabeil, N.F. Factors Influencing SMEs Adoption of Social Media Marketing. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyakulumbye, S.; Pather, S. Understanding ICT adoption amongst SMEs in Uganda: Towards a participatory design model to enhance technology diffusion. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2021, 14, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K.; Chan, F.T.S.; Venkatesh, V.G. Evaluating the Drivers to Information and Communication Technology for Effective Sustainability Initiatives in Supply Chains. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2018, 17, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-O. Analysis of Trends in Research on Instruction Models for ICT Teaching and Learning. J. Digit. Converg. 2014, 12, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Won, J.Y.; Park, M.J. Smart factory adoption in small and medium-sized enterprises: Empirical evidence of manufacturing industry in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 157, 120117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.P.; Trakulmaykee, N. An empirical study on factors affecting e-commerce adoption among SMEs in west Malaysia. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. The importance of information and communication technologies (ICTs): An integration of the extant literature on ICT adoption in small and medium enterprises. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 274–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.S. Factors affecting the adoption of computerized accounting system (CAS) among smes in Jaffna District. SAARJ J. Bank. Insur. Res. 2019, 8, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sood, S.; Bala, R. Passive leadership styles and perceived procrastination in leaders: A PLS-SEM approach. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, K.-K.; Ahmed, E.M.; Tan, K.S. Factors influencing Malaysian small and medium enterprises adoption of electronic government procurement. J. Public Procure. 2020, 20, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Nicotra, M.; Del Giudice, M.; Krueger, N.; Gregori, G. A microfoundational perspective on SMEs’ growth in the digital transformation era. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modelling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Hoyle, R., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M. Structural equation modeling techniques and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 7, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Hack-Polay, D.; Shafique, S.; Igwe, P.A. Dynamic capability of the firm: Analysis of the impact of internationalisation on SME performance in an emerging economy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. ahead-of-print. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.P.; Cham, T.-H.; Chang, Y.-S.; Lim, X.-J. Advancing on weighted PLS-SEM in examining the trust-based recommendation system in pioneering product promotion effectiveness. Qual. Quant. 2021, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construct with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.; Fernandez, W.; Rowlands, B. Qualitative Methods in IS/IT Research: Issues, Contributions and Challenges. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration [Special Issue on Research Methodology]. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A.; Diamantopoulos, A. In defence of causal–formative indicators: A minority report. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongori, H.; Migiro, S.O. Information and communication technologies adoption in SMEs: Literature review. J. Chin. Entrep. 2010, 2, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particulars | Category | % | Particulars | Category | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female | 85.09 14.91 | Sector of business | Primary Manufacturing Service | 31.50 53.70 14.80 |

| Area | Alimosho Agege Ojo Badagry | 23.6 28.88 36.95 10.56 | Business Type | Sole trader Partnership Family Co-operative Private Limited | 28.94 24.22 34.78 19.88 2.17 |

| Model | Particulars |

|---|---|

| First Order Yi = ∆y.ηj + εi | yi = manifest variables ∆y = loadings of first-order latent variables ηj = first-order latent variables (Technology–Organisation–Environment-related barriers) εi = measurement error of manifest variables |

| Second Order ηj = Γ.ξk + ζj | ηj = first-order factors (e.g., technology-related barriers) Γ. = loadings of second-order latent variables ξk = second-order latent variables (environmental-related barriers) ζj = measurement error of first-order factors |

| Constructs | Items summary | Loadings | CR | CA | rho_A | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology (H1) | Security issues Cost of implementation Network quality | 0.869 0.866 0.828 | 0.890 | 0.815 | 0.817 | 0.731 |

| Organisation (H2) Environment (H3) | Lack of expertise Lack of funds Unsuitability for business Lack of use by customers Lack of government support Cultural-related issues Legal and regulatory issues Lack of awareness Other factors | 0.831 0.813 0.834 0.829 0.815 0.849 0.805 0.787 0.817 | 0.883 0.925 | 0.801 0.901 | 0.805 0.902 | 0.716 0.668 |

| Original Sample Coefficient | Sample Mean Coefficient | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | p Values | T Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dev. ICTs-Env. | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 385.812 |

| Dev. ICTs-Org. | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 128.673 |

| Dev. ICTs-Tech. | 0.952 | 0.952 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 152.759 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Security issues is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.869 | 44.822 | Supported |

| H1b: Costs of implementation is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.866 | 42.016 | Supported |

| H1c: Network quality is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.828 | 28.192 | Supported |

| H2a: Unsuitability for business is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.831 | 30.309 | Supported |

| H2b: Lack of expertise is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.873 | 45.787 | Supported |

| H2c: Lack of funds is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.834 | 28.927 | Supported |

| H3a: Low use by customers is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.829 | 26.714 | Supported |

| H3b: Lack of government support is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.815 | 23.804 | Supported |

| H3c: Cultural issues is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.849 | 35.008 | Supported |

| H3d: Legal and regulatory issues is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.805 | 23.486 | Supported |

| H3e: Lack of awareness is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.787 | 20.807 | Supported |

| H3f: Other factors is positively related to advanced ICT adaptation. | 0.817 | 24.114 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadiq, O.; Hack-Polay, D.; Fuller, T.; Rahman, M. Barriers to the Effective Integration of Developed ICT for SMEs in Rural NIGERIA. Businesses 2022, 2, 501-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2040032

Sadiq O, Hack-Polay D, Fuller T, Rahman M. Barriers to the Effective Integration of Developed ICT for SMEs in Rural NIGERIA. Businesses. 2022; 2(4):501-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2040032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadiq, Olusegun, Dieu Hack-Polay, Ted Fuller, and Mahfuzur Rahman. 2022. "Barriers to the Effective Integration of Developed ICT for SMEs in Rural NIGERIA" Businesses 2, no. 4: 501-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2040032

APA StyleSadiq, O., Hack-Polay, D., Fuller, T., & Rahman, M. (2022). Barriers to the Effective Integration of Developed ICT for SMEs in Rural NIGERIA. Businesses, 2(4), 501-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2040032