Abstract

In this exploratory study, we employed multiple case-based approaches to explore and advance our understanding of how some entrepreneurial firms in unstable and extreme contexts achieve and sustain high growth. We included five Palestinian entrepreneurial firms from different sectors. The findings suggest that several factors play a significant role in how entrepreneurial firms in an extreme context such as Palestine achieve and sustain high growth. These factors are innovation and know-how, family growth, opportunities for exploration and exploitation, human capital, focusing strategy, business and social networks, foreign aid, and flexibility and adaptability.

1. Introduction

For almost five decades, high-growth firms (HGFs) have attracted interest from policymakers, governments, practitioners, and academics in many countries [1]. There is significant evidence that high-growth firms contribute significantly to employment and economic growth [2]. Plenty of literature has sought to identify the main determinants and characteristics of firm growth, and although several factors have been put forward, nevertheless researchers have only been able to explain a small fraction of the variation in firm growth [1,3,4,5,6]. However, HGFs may lead to higher levels of innovation [3], knowledge generation [7], more internationalization [8], and export orientation [9]; it can also enhance the growth of the industries [2]. Moreover, research has shown that HGFs exist in all industries and include all firm sizes, but small and young firms are over-represented [10,11]. Additionally, high growth in the firm is rarely persistent [12,13] and therefore, high growth in one period does not guarantee sustained high growth [14]. HGFs offer a unique context for understanding the firm’s growth [15]. High growth in firms has been one of the essential topics in entrepreneurship research in recent years [5,11,16]. In fact, various stakeholder groups are interested in entrepreneurial and business growth, which enhances the knowledge generation and the contribution of academic researchers [1].

Given the abundance of work on HGFs, the scholars’ knowledge of the drivers leading to high growth remains fragmented and without any systematic assessment [6,17,18]. Likewise, not just many drivers and characteristics of high-growth firms remain unknown, but also the dynamic nature and activities of HGFs and how firms overcome the challenges they face to sustain growth. The high-growth entrepreneurship literature and firm growth research have focused mainly on the questions of ‘how many’ and ‘how much” rather than questions of ‘how’ and ‘why’ firms achieve growth [1,5,19], and the conditions under which firms grow has been ignored [20]. As less research has dealt with the issue of how firms grow, McKelvie and Wiklund [5] suggest that we need to obtain a better grasp of the answer to the question of “how” firms grow and what mode of growth firms use and why. However, it is essential to understand how entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain the high-growth, particularly within the extreme context where the firms conduct their operations in unstable, harsh, and dynamic environments. According to Brown et al. [5], high-growth entrepreneurship literature is theoretically and empirically underdeveloped [1,18]. Investigating HGFs in extreme and unstable environments will provide a unique opportunity to understand the dynamic nature, characteristics, and determinants of the HGFs [15] that foster the development and sustainability of the firms. However, the literature so far does not adequately explore the link between HGFs and extreme contexts. HGFs are disproportionally responsible for job creation in most developing countries, but there is little information about how the firms sustain their performance and growth over time [15]. Due to the lack of research in extreme contexts, Alvi et al. [21] called for more substantive and sustained consideration of the context of research on entrepreneurship under extreme conditions. We aim for the current study to understand how entrepreneurs can achieve and sustain high growth in their firms in an unstable, harsh, and extreme context where most entrepreneurs are struggling to merely survive. Palestine, which consists of the West Bank and Gaza, presents an extreme context as it continues to be a territory that is occupied by a foreign authority [22] and that poses unique challenges for entrepreneurs [23]. Undertaking such a task will enlighten the contextual challenges that entrepreneurial firms must routinely appease to survive and grow in an environment characterized by a high level of uncertainty, ambiguity, and turbulence. However, Hannah et al. [24] defines the extreme context as, “An environment where one or more extreme events are occurring or are likely to occur that may exceed the organization’s capacity to prevent and result in an extensive and intolerable magnitude of physical, psychological, or material consequences to—or in close physical or psycho-social proximity to—organization members”. Given the conditions imposed upon local Palestinian entrepreneurs and countless unique challenges that are cast on the entrepreneurs and firms [21,25,26,27]. Palestine sufficiently qualified as an extreme context and, therefore, an appropriate research site for the present study. However, there is a shortage of scholarly work in entrepreneurship research in this area. Therefore, such a unique and extreme context needs more attention from scholars in entrepreneurship and management in general. The Palestinian economy has suffered from volatile and unsustainable growth over the previous years. Palestine’s firms face many challenges due to Israeli measures that restrict import and export activities and fundamental freedoms to trade. Additionally, policies of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip have been devastating to businesses, causing obstacles and severe damage to infrastructure, capital, labor movements, and productivity. Therefore, Israel’s policies and restrictions have resulted in weak levels of competitiveness, the closure of thousands of businesses, and downscaling. Based on the above, it is worth gaining deeper insights into how some of Palestine’s entrepreneurial firms are fruitful and still able to achieve high growth, even though they work within such a daunting, dynamic, and complicated environment. Indeed, in the current article, we attempt to answer the following research question:

How Do Entrepreneurial Firms Achieve and Sustain High—Growth in Unstable and Extreme Contexts?

In the current study, we make two contributions. First, we contribute context-level empirical findings to the body research of HGFs by investigating how firms achieve and sustain growth in extreme contexts, as ‘our current understanding remains limited’ [28]. Second, we seek to contribute to more understanding of entrepreneurial high-growth phenomenon within a dynamic and unstable environment in which entrepreneurial firms are embedded significantly. Given the lack of research on extreme and unstable contexts, focusing on HGFs in an unstable environment [29], and within an extreme context like Palestine will yield new knowledge and insights that enrich established findings in the HGFs’ entrepreneurship literature [30]. According to Alvi et al. [21], there is a lacuna in the extant literature conceptualizing the emergence, dynamics, and outcomes of entrepreneurial phenomena in extreme contexts.

Since the present research follows the objectives of understanding how some entrepreneurial firms can achieve high-growth rates in an unstable and extreme context such as Palestine, a qualitative research approach would be the most proper for the study at hand. Therefore, we adopted a qualitative approach to address the objectives of the present study. Hence, we applied an in-depth multiple case studies approach [31,32,33]; therefore, five cases were purposefully selected from Palestine to collect the data.

Our paper proceeds as follows: in Section 2, we present a review of the literature investigating research in high-growth entrepreneurial firms and background on the context. Section 3 describes the methodology and reports details on the data collection process. Section 4 discusses the results emerging from case studies and concludes with the suggestion of some propositions; Section 5 concludes, acknowledges limitations, and suggests future research developments.

2. The Literature Review

2.1. High-Growth Firms’ Definitions and Concepts

Undoubtedly, high-growth firms contribute significantly to employment and economic growth [2,17,19,34,35]. Some empirical facts about HGFs have emerged. For example, HGFs are found in all regions [36]; they are more R&D intensive; they are found in almost every sector; they tend to be younger and smaller than their normal-growing counterparts [36]; and, additionally, patterns of growth among HGFs cannot be sustained for extended periods [11,35,37,38]. Consequently, high growth is rarely persistent in firms [12,13]. Therefore, high growth in one period of time does not guarantee sustained high growth [14,39]. Sustaining high growth is known in the literature as high-growth persistence. Less attention is devoted to investigating the persistence of high growth in the firms, as there is a debate on the existence of persistently high-growing firms [13,39]. Previous empirical studies on growth persistence (see, e.g., [13,17,40,41,42]) provide limited evidence of persistence. However, Moschella et al. [42] discovered by utilizing a sample of Chinese manufacturing firms that some relevant firm characteristics (such as productivity and innovation, profitability, and financial structure) do not enable the prediction of persistent HGFs. Moreover, according to Coad et al. [43], younger enterprises are more likely to have subsequent growth periods than older ones.

Although the literature on high-growth firms has been growing in both quantity and quality, our knowledge of the nature of HGFs remains nascent [18], and the high-growth entrepreneurship literature base needs further development [17]. Additionally, despite the rich work on high-growth firms, the scholars’ knowledge of the factors that lead to high growth remains fragmented and without any systematic assessment [6,17,18]. Demir et al. (2016) suggest that the three most important reasons for the fragmented nature of a High-growth firm in research stemming from inconsistent definitions, sampling challenges, and organizational complexity have not yet been developed [6]. However, HGFs can be measured differently [43]. There is an ongoing debate over the merits and drawbacks of different definitions [17,44,45,46,47]. Indeed, much of the early literature failed to use a consistent metric for measuring growth in the firm [19], drawing on a range of metrics such as employment, turnover, and assets [11]. Yet, there is little agreement regarding measures of high growth in the literature. The source of disagreements tends to relate to the specifics regarding the pace of growth, the nature of how growth is measured, and the number of years in which growth occurs [5]. Several studies have used relative annual growth, or a firm’s growth rate relative to the overall population of firms in industry, region, or country, as criteria for high growth. HGFs literature examines three diverse types of growth; growth in sales (interchangeably called turnover or revenue); growth in the number of employees [48,49]; productivity growth [2]. Indeed, definitional issues are important because conceptions of business growth vary markedly between scholars and practitioners [50]. Scholars agree that HGFs can be defined as “firms growing at or above a particular pace, measured either in terms of growth between a start and end year or as annualized growth over a specific number of years” [17]. However, in the current study, we rely on the OECD’s definition, an HGF is considered to be ‘an enterprise with average annualized growth (in a number of employees or turnover) greater than 20% per annum, over three years, with a minimum of ten employees at the beginning of the growth period’ [51]. This implies that researchers should measure different growth forms with varying growth measures. Delmar et al. [11] believe that a single growth measure would likely provide knowledge about only one form of organizational growth. Therefore, many studies rely on the OECD definition because they have found a link between employment growth and turnover growth measures [52]. Although many early studies focused on employment growth [47], there is now increasing use of growth in turnover to define HGFs (e.g., [2,8]).

2.2. High Growth in the Entrepreneurship Literature

HGFs research is a growing field in management, entrepreneurship, and economics. For almost 50 years, there has been substantial interest in entrepreneurial and business growth from policymakers, practitioners, and academics. The topic of a firm’s growth as a focus of entrepreneurship research has attracted much interest and stimulated considerable empirical research [5,11]. High growth in entrepreneurial firms represents a relevant research topic and needs more attention from entrepreneurship scholars since the phenomenon constitutes a theoretical and empirical challenge to the recent literature on entrepreneurship [53]. Indicating entrepreneurial success and identifying future HGFs are challenging, even with combining large datasets and advanced methods [54]. Achtenhagen et al. (2010, p. 309) note, despite the fact that it is entrepreneurs and business owners “as the enactors of business growth” who decide whether to grow their businesses or not, they are not given the central role they deserve. However, the high-growth entrepreneurship literature is theoretically and empirically underdeveloped [1,11]. Hence, for the accumulation of knowledge, there needs to be a shift of attention beyond the use of different empirical proxies of growth toward the development of more fine-grained theorizing [49]. Indeed, fundamental questions remain unanswered as “little is still known about the phenomenon, and conceptual development has been limited” [6]. Generally speaking, the high-growth entrepreneurship literature and firm growth research have been highly focused on the questions of ‘how many’ and ‘how much’ rather than questions of ‘how’ and ‘why’ firms achieve growth [1,5,15,19]. For example, McKelvie and Wiklund (2010, p. 261), noted: “the impatience of researchers to prematurely address the question of ‘how much?’ before adequately providing answers to the question ‘how?’”. McKelvie and Wiklund (2010) argue that how firms grow needs to be understood before the question of how much firms grow can be addressed. Research focusing on questions such as how firms grow, why they grow according to different patterns, how the decisions about whether to grow or not are made by entrepreneurs, and the dimensions of the contexts in which growth occurs, have been neglected [55,56]. Moreover, there has been disquiet concerning a perceived lack of well-founded knowledge about the causes, effects, and process of growth [1,57], and of a holistic understanding of the phenomenon, especially among academics. A recent study by Demir et al. (2016), after a systematic review of the empirical literature concerning high-growth firms based on 39 articles, identified five drivers for high growth: human capital, strategy, human resources management, innovation, and capabilities. Thus, an inevitable consequence of this has been a narrowing of the research focus, and therefore ‘our current understanding remains limited’ [28]. Hence, more research is necessary [19]. An essential contribution of this paper is that it addresses the lack of theoretical development by investigating high-growth entrepreneurial firms in extreme and unstable contexts like Palestine. Therefore, we aim to gain new and better insights on how some firms can achieve and sustain high growth even though it conducts their business in unstable, harsh, and extreme contexts where most entrepreneurs are struggling to merely survive. This might help to stimulate discourse and start to bridge the gap between “scholarly interest and entrepreneurial practice” identified by Achtenhagen et al. (2010) as well as provide insights that may help influence policy decisions, and provide up-to-date and appropriate information for practitioners.

2.3. Background on the Extreme Context (Palestine)

Palestine’s firms face many challenges, which means that few businesses are capable of maintaining high-growth rates, especially for extended periods. The Palestinian economy has experienced volatile and unsustainable growth over the previous years, and it faces many challenges as a result of Israeli measures that restrict imports, exports, activities, and freedom of trade. The Israeli occupation is strictly impeding international trade, particularly with export restrictions and strict border policies, involving time-consuming inspections and Israeli customs. Consequently, Israel’s policies and restrictions have resulted in weak competitiveness, the closure of thousands of businesses, and downscaling. According to the World Bank report (2017, p. 7) Palestinian economy “has been losing this capacity as a result of a poor business climate mainly driven by externally-imposed restrictions on trade and access to resources in addition to the lack of political stability.” In fact, the structure of the Palestinian’ economy has substantially deteriorated since the 1990s. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in manufacturing halved in the last twenty-five years. Currently, unemployment is approaching 30 percent on average, with youth unemployment in Gaza twice as high [58]. Moreover, the lack of progress in the peace process and Israeli restrictions on trade, movement, and access to resources, as well as the internal political divide between the West Bank and Gaza and a challenging business environment and continue to stand in the way of a sustainable economic recovery in Palestine. As Palestine has a small economy, achieving a sustainable growth path depends to a large extent on its capability to compete in regional and global markets and increase its exports of goods and services. Another challenge that Palestinian firms face is the high costs that firms are exposed to, for instance, the cost of electricity, water, and fuel represents 20% of the total cost of manufacturing. Palestinian products compete locally with cheap imported products. Therefore, manufacturing companies are on average running at 50% of their production capacity. Moreover, there is no regulation on dumping and no protection for infant Palestinian domestic industries. Palestinian firms are young, with 46% of total registered companies having less than ten years in business, and small, with 89% of total registered firms having between one and four employees. The Palestinian economy is failing to generate the jobs and incomes needed to improve living standards for Palestinians. According to Economic Monitor [59], Palestine has displayed economic growth that is artificial, insufficient, and volatile.

It is important to note that the overwhelming majority of studies have been conducted in North America and Europe. Although some work has been done in China [60], sub-Saharan Africa [34], and New Zealand [61,62], the current understanding of HGFs is very much predicated on observations from a very limited number of similar economies more precisely advanced and industrial countries. HGFs in developing and unstable contexts are recognized as differing somewhat from those within developed countries [63] and thus require further research and investigation to provide additional insights into the growth phenomenon [1]. There is also an overall need for research on entrepreneurial phenomena in general in developing economies which would enrich established findings in the literature [29]. Our study is motivated by this gap in the scholarly literature and the need for better policy guidance. Hence, we investigate how HGFs achieve high growth in developing and unstable economies where firms encounter many challenges that are not valid in other contexts. However, it is worth it to achieve a deeper understanding of how some Palestinian entrepreneurial firms are fruitful and still able to achieve high growth, even though they work within such a daunting and complicated environment. Additionally, it is vital to understand the processes and the success factors that stand behind the high-growth firms in Palestine, and that can be considered as a benchmark for other firms conducting their business in a similar environment. Actually, to the knowledge of the researchers, there is no research to date that has addressed high-growth entrepreneurial firms in unstable and turbulent economies like Palestine. Finally, we aim to come up with new and profound insights that contribute to high-growth entrepreneurial literature.

3. Research Methodology

Since the present research follows the objectives of understanding how entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain high growth in an unstable and extreme context, a qualitative research approach would be the most proper for the study at hand. The basic ideas of grounded theory [64] were taken in the study because of its specific purpose of building theory from qualitative data and interpretation. Moreover, it is appropriate for achieving a new understanding of the intricate details of a particular phenomenon under investigation [65]. More specifically, our most important aim is to build a theory on HGFs and the entrepreneurship phenomenon and broaden the existing theories by extending and refining the categories and relationships left out of the literature [66]. However, we adopted an exploratory approach in our empirical analysis. Hence, we applied a multiple case study method, similar to approaches introduced by Eisenhardt (1989) and Yin (2003), as the present study aims at answering the “how” question regarding a contemporary set of events over which the researcher has no control. Indeed, a multiple case study can be seen as a preferred research strategy due to the explanatory nature of the research questions and because it allows both an in-depth examination and the explanation of cause-and-effect relationships of each, as well as the identification of contingent variables that distinguish each case from the other. Case examples can help bridge the gap between academia and industry [67]. The case firms were selected for theoretical reasons rather than random sampling. Furthermore, the selection of the firms for investigation was based on an overall theoretical perspective, as recommended in Eisenhardt’s study (1989). Hence, we followed Yin [68] in selected cases where the phenomenon under study is transparently observable. Eisenhardt (1989) recommends that researchers choose between four and ten cases, as it may be difficult to generate a complex theory with less than four, while greater than ten can result in “death by data asphyxiation” [69]. Five entrepreneurial high-growth Palestinian firms from different business sectors were selected for this study. These firms were chosen to be the representative cases to study the phenomenon due to their success and experiences in achieving high growth rates. To be eligible as a high-growth entrepreneurial firm, the following criteria were taken into account: (1) the firm should be Palestinian, (2) the firm should have achieved an average annualized growth in turnover greater than 20% per annum, over a three-year period, with a minimum of ten employees at the beginning of the growth period [51].

In the present study, some sampling strategies were used to select the case firms that met the criteria outlined above. These included opportunistic, convenience, and theoretical selection methods [70].

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

To identify a shortlist of HGFs in Palestine, we met experts in the Palestinian economy. For example, the Federation of Palestinian Chambers of Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture Palestine, the Palestinian Trade Center (PALTARDE), and the Palestinian Federation of Industries provided an initial list and references for HGFs from their professional networks. To build and elaborate on the theory, we searched for a purposeful sample of HGFs; therefore, we selected a subsample of firms that met the above conditions. Several sampling strategies were used to select the case firms. These included opportunistic, convenience, snowballing, and theoretical selection methods [70]. Five firms from different sectors were chosen to participate in the interviews, as shown in Table 1. The final sample included different manufacturing industries and services, with the firm size ranging between 48 and 160 employees and the firm age ranging between 7 to 27 years since its foundation. The fieldwork was carried out over four months, specifically in the West Bank, from August 2017 until October 2017. It was impossible to include the Gaza Strip due to its complicated political situation. However, multiple information sources were used to gather data for each case firm. The primary form of data collection was a semi-structured interview guided by a list of topics. In the interview process, semi-structured, open-ended interviews were conducted. The approach made it possible to raise the “leading” questions and pose further, more detailed questions [68]. Each interview lasted on average, between 55–85 min. Rapport and mutual trust were established with the selected interviewee at the outset of each case; the interviewees were mainly founders or senior managers. The interviewee was briefed about the research project through a telephone call. The interview concluded with an open-ended question about the interviewees’ overall opinion regarding the activities related to growth. However, the interviewer followed the guidelines developed by Yin (1994) to minimize the risk of providing inaccurate or biased data. The primary data were supplemented by secondary archival data sources, such as websites, annual reports, catalogs, newsletters, news articles, and YouTube videos about the companies. Additionally, at this stage, a telephone follow-up and e-mail communication were carried out with the respondents to collect further information and clarify any ambiguous issues. However, the interviews at each firm followed a similar procedure. The interviewees were first asked to describe and present some information about their businesses, including demographic (e.g., age, size) and historical data, and then explain their firm’s growth and success determinations and challenges.

Table 1.

Information on the case firms.

3.2. Data Analysis

All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A second listening was conducted to ensure correspondence between the recorded and transcribed data. Before being analyzed, information gathered through the case studies was manipulated by applying data categorization and contextualization techniques [70]. Then a structured process was followed for data analysis, consisting of a preliminary within-case study and an explanation-building investigation, followed by a cross-case comparison. These structured procedures for data collection and analysis and the use of the semi-structured interview guide helped enhance the reliability of the research [33]. In the data ordering phase, a detailed history of each firm was drawn up based on interviews and written documents. As Pettigrew (1990) has noted, sequentially organizing incoherent aspects is a significant step in understanding the causal links between events. In the data analysis phase, we analyzed the data according to the following steps. First, as Eisenhardt (1989) suggests, we started data analysis by sifting through all the data, discarding what is irrelevant, and bringing together the most critical elements. Wolcott [71] argues that the key to qualitative work is not to accumulate all the data that one can but to identify and reveal the essences with sufficient context to allow the reader to understand the situations in which the individuals are immersed. Second, we iteratively analyzed the qualitative data by moving back and forth between the data and an emerging structure of theoretical arguments that responded to the theory questions presented above [66,72]. Third, the collected information was manipulated before being analyzed by applying data categorization and contextualization techniques [72]. In fact, checklists and event listings were used to identify critical factors related to the research questions [72].

4. Findings and Discussion

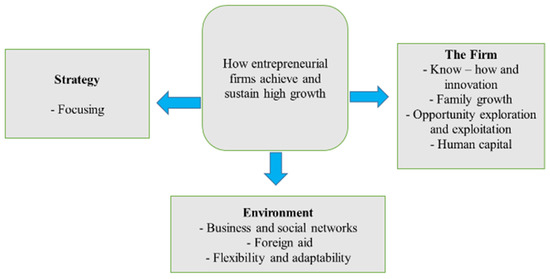

The present exploratory study is meant to shed light on how entrepreneurial firms in unstable and extreme contexts achieve and sustain growth. Palestinian firms face unique challenges rooted in the conditions of the occupation. The occupation impedes economic development and limits the region’s long-term planning, which makes Palestine an extreme context. Even though most firms struggle to survive, some can achieve and sustain high growth. However, we analyzed the data from interviews with the founders or managers of entrepreneurial firms and secondary data. The interviewee that we spoke with described their experiences regarding how they achieve and sustain high growth. As we can see in Figure 1, the empirical evidence collected suggests that several determinations or factors play a significant role in how entrepreneurial firms in extreme contexts such as Palestine achieve and sustain high growth. We classify and discuss these factors within three dimensions, the firm, strategy, and the environment. In the following section, we discuss these factors and prove with the interviewee’s statements how these firms succeed in achieving and sustaining high growth.

Figure 1.

How entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain high growth in extreme context.

4.1. The Firm

Within the firm dimension, we explain four factors related to the firm itself. These factors play a significant role in how firms achieve and sustain high growth in unstable and extreme contexts. These factors are as follows:

- -

- Innovation and know-how

Innovation refers to new ways of doing things, commonly associated with new products or processes [73]. The innovation and know-how factor plays a significant role in the case of firms achieving and sustaining high growth. However, our analysis shows that possessing know-how and pursuing innovative behavior allows the firms to have an advantage over the competitors. The following statements made by three interviewees in the course of the interviews were directed toward understanding the role of innovation and know-how:

The co-founder of firm A pointed out, “We distinguish ourselves by the innovative products that we provide as well as the fast and reliable services that we have committed to offering to our customers.”

The founder of firm B stated: “I started my business as a wireless internet provider based on know-how and experience that I possessed during my previous work on international companies abroad like Motorola.”

The founder of firm C remarked, “I was interested in developing and improving our security doors to meet the international specifications; therefore, we put exceptional efforts to gain the quality certificate for our doors from a specialized center in England.”

Drawing on the above statements, we can conclude that innovation and know-how are essential factors in achieving high growth.

Proposition 1.

Innovation and know-how play an important role in achieving high growth in extreme contexts.

- -

- Family growth

As most of the entrepreneurial firms in Palestine are family firms, most of the case firms in the current study are family firms. The results show that a critical factor of high growth is the growing number of people and generations of family members involved in the business. For example, when a new generation gets involved in the business, a greater need to achieve growth in the family business becomes a central issue. For instance, the general manager of firm D pointed out: “Once the third generation has involved in the business, we changed our strategy for more rapidly growing. However, our current plan is open new branch every year.” Likewise, the founder of firm C mentions: “Because one of my sons and my nephew have joined the business and the other sons will join us soon, growing the business became very important; therefore, I established a new factory with international standards.” Another example is provided by the international manager of firm E: “All the plans and activities in the business have changed toward more growth as the third generation has started to join the business.”

Proposition 2.

Entrepreneurial firms tend to grow more as a result of family growth.

- -

- Opportunities for exploration and exploitation

Growth depends primarily on recognizing and exploiting profitable opportunities to increase turnover. Therefore, firms that want to achieve high growth should hold proactive perspectives toward the opportunities in the external environment. The discovery and exploitation of specific opportunities for the case firms led to the launch of a steady growth process in these firms. Hence, these exploited opportunities have led to a leap in the returns of these firms. The following statements concerning this issue were made by three interviewees from firms A, C, and D, respectively:

Firm A: “In 2011 the boom in sales started after we established our new line for producing envelopes. Currently, we work 24/7 producing envelopes to meet the market demand.”

Firm C: “Our business took a new direction in terms of growth in sales when we established the new line for producing the security doors.”

Firm D: “Our strategies of opening a new branch every year and selling at the cheapest prices in the market were the main reasons for achieving growth.”

Proposition 3.

Recognizing and exploiting the right opportunities in the market is a crucial element of the growth process.

- -

- Human capital

Human capital, as defined by Coff [74], is “knowledge that is embodied in people.” Human capital includes the education level and skills of the founder-manager, management experience, cognitive ability, and domain experience. However, the Palestinian people are characterized by high education levels and good human capital. In our cases, most of the business founders are highly educated with respected levels of experience. Moreover, the employees of these firms are qualified, educated hard workers. The following statements of the interviewees clarify this issue:

Firm A: “I have a bachelor’s degree in computer science from the USA, and before starting my business, I gained excellent experiences through working in a company with a good reputation as well as working with United Nations Agency.”

Firm B: “I am a communications engineer, and I worked for a long time at Motorola where I could build my skills and capabilities in the telecommunication field. The employees in my business have joined the company with a lack of skills and experiences, but because they are motivated and hard workers they learned and improved rapidly.”

Firm D: “The new generation is more educated as they graduated from respected universities in the USA and Europe. This generation with the right skills and capabilities made a change in the strategy and pushed new blood into the firm.”

Proposition 4.

Human capital plays a significant role in achieving high growth for entrepreneurial firms in unstable and extreme contexts.

4.2. The Strategy

Our findings show that HGFs strategy plays a significant role in achieving and sustaining high growth.

- -

- Focusing strategy

The current study’s findings indicate that the focusing strategy is the most used strategy by case firms. However, the following statements by the interviewee explain that:

Firm B: “We are the number one firm in the Palestinian market as an internet wireless provider. We gain this position because we focus on one technology and one service. The market still offers many opportunities, and currently, we utilize all our available capacity.”

Firm C: “Our strategy relies on providing more quality products by using the same production lines. We focus on what we can do and compete better. However, we plan to enter new markets with the same but higher technology products.”

Firm D: “Our plans and investments will focus on increasing sales on the same branches as well as opening new branches in new regions. Additionally, we keep the same policy on our supermarket chain which is the wide selection and lowest prices.”

Proposition 5.

The focusing strategy is the most used strategy in the extreme context.

4.3. The Environment

The environments where entrepreneurial firms conduct their businesses play a significant role in how these firms achieve growth. Palestine as an unstable and extreme environment needs different approaches to conform to achieve growth. The study found three major factors in the environment that firms have to consider for achieving high growth.

- -

- Flexibility, and adaptability:

Palestinian entrepreneurial firms face many obstacles as a result of occupation and political uncertainty. The occupation impedes the development of the Palestinian economy because it is mainly controlled by Israel. Moreover, managing firms in such harsh and extreme contexts limit long-term planning as the situations in the region are subject to change dramatically from day to day. Hence, it is indispensable for the firms in Palestine to be very flexible and able to adapt to all situations and potential challenges. The following statements were made by four interviewees regarding this issue:

Firm A: “The costs are particularly high when shipping products to Israel or to the Gaza Strip, where goods are downloaded and then uploaded into other trucks. This process needs extra cost and time as well as the possibility of goods damage. In addition to the security screening and deliberate delays in Israel ports to importing products and raw materials from abroad.”

Firm B: “Israel occupation is an economic occupation where the Israeli side does not stop inventing impediments to Palestinian firms. They want to stay ahead of Palestinian companies to prevent them from competing with Israeli companies. In spite of all obstacles imposed by Israel’s side, we became familiar with these barriers, and we adapt to them quickly and with an immense insistence on success.”

Firm C: “Doing business in Palestine is very complicated, and success is relative, but we are struggling to survive despite all these circumstances and challenges that we face.”

Firm E: “We are as a dairy company affected badly by the Israeli procedures for the movement of goods. For example, we have been prevented several times by the Israelis to sell our products to the Palestinians in Jerusalem. However, these actions do not consist of free trade; therefore, we resorted to international institutions to stop these arbitrary measures. We don’t have choices, we should adapt to such challenges and barriers for a better future.”

Proposition 6.

Flexibility and adaptability to harsh and unstable environments is crucial for growth in extreme contexts.

- -

- Foreign aid

Foreign aid provided by governments and international organizations for Palestinians is used as a means for developing and sustaining the local economy. However, this aid has been reflected significantly in the economic, social, and political scene in Palestine. Our findings indicate that foreign aid plays a vital role for some entrepreneurial firms that have received both financial and technical assistance. For example, the founder of firm C mentioned, “I have excellent relationships with several institutions which enable me to contact USAID officials who visit my firm. Then, they expressed their willingness to provide financial support for buying new and sophisticated machines for developing our firm’s operations. Fortunately, we were able to update the production process which in turn raised our competitiveness.” Also, the founder of firm B pointed out, “We have benefited greatly from international organizations like USAID and World Bank because we were the executing company for the projects that have been funded by them to link schools and hospitals with internet in West Bank.”

Proposition 7.

Foreign aid to firms in extreme and unstable contexts is playing a vital role in achieving growth.

- -

- Business and social networks

Networks of relationships are often characterized as informal and personal or formal and professional. However, according to our findings and regardless of the category of the network, it plays a significant role in achieving and sustaining high growth. Networks are essential for acquiring knowledge, business referrals, and financial resources. Having extensive social and business networks are valuable assets that can help entrepreneurial firms obtain access to information, opportunities, as well as resources.

For instance, the owner of firm D remarked: “My privileged relationships with many institutions and organizations gave me the opportunity to contact international institutions for gaining the needed fund. Concerning social relations, it has had a major role in obtaining the necessary funding and support, especially from relatives.” In the same vein, the general manager at firm B mentioned:” Although we are a large and extended family, we enjoy and share strong and solid relationships. Therefore, most of the resources we need are provided by family members.” Finally, the co-founder of firm A explained, “At the inception of our firm I borrowed money from one of my relatives. However, the major part of our success depended on our social and business relationships. We have enjoyed a distinguished reputation as an expert in computer science and technology.”

Proposition 8.

Strong business and social networks impact largely how entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain high growth in extreme contexts.

5. Conclusions

A significant objective for practitioners and public policy is to ensure that entrepreneurial firms can achieve and sustain high growth. The present study contributed to the body of research on the HGFs and entrepreneurship literature by displaying and identifying a rich array of factors that significantly affect how entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain high growth in unstable and extreme contexts. However, knowledge of the factors that lead to high growth, particularly in extreme contexts, remains fragmented and without any systematic assessment. By conducting a qualitative study and using a multiple case study approach on high–growth entrepreneurial firms in Palestine, we were able to identify nine essential factors that have a significant effect on achieving high growth. We classified these factors into three dimensions, the firm, strategy, and the environment. The study reveals important factors: innovation and know-how, family growth, exploration and exploitation of opportunities, human capital, focusing strategy, business, and social networks, foreign aid, and flexibility and adaptability. We believe that these new findings could be useful not only to academics but also to managers and practitioners. This work shows there is no single way to achieve high growth and there are different factors that influence the possibility of achieving and sustaining high growth.

5.1. Practical Implications

For policymakers and practitioners who are interested in HGFs, our findings have several ramifications. First, government policies should foster a more competitive business climate by reducing the burden imposed by formal institutions to support the HGF’s work in an unstable economy vulnerable to numerous challenges. Second, policymakers should provide financial and management support to firms with high growth potential, such as family and entrepreneurial firms, which may bring greater returns than focusing solely on early-stage ventures. As a result, support may offer incentives that inspire experienced entrepreneurs who have already experienced significant growth and are still driven to do so. Finally, we believe practitioners could benefit from this study somehow. Although a variety of high growth-related factors have been addressed in this study, there are likely still more that needs to be addressed. However, we hope our results will help the managers of entrepreneurial firms to achieve and maintain high growth.

5.2. Recommendations for Future Research

Our results provide opportunities for future research about HGFs. We provide researchers with some level of knowledge about HGFs in extreme contexts. We hope our study will stimulate future research on this complex yet important topic in HGFs, entrepreneurship, and management. However, our study offers eight propositions for further quantitative analysis, hoping that they will encourage firm growth and entrepreneurship scholars to examine whether the results of our analysis can be statistically generalized. We advise academics and scholars interested in this area to do empirical, analytical research using a larger sample of high-growth companies in other extreme contexts. Doing this will validate the pertinent variables and dimensions that could distinguish high-growth firms from firms with average growth. Furthermore, other research along these lines should use different measures of high growth.

Growth is a function of the decisions entrepreneurs make about how and where they should grow their firms and the extent to which other factors are in place that enable growth to occur. Therefore, further empirical research on the relationship between entrepreneurs’ leadership styles and growth decisions will improve its understanding of this complex process.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

We are conscious of several limitations of the present research. Two of these, in particular, need to be highlighted. The first is the small sample size (5 high-growth entrepreneurial firms) and related to this, the question about transferring the results obtained to other firms within the same contexts. However, our findings should not be generalized to any population of firms due to methodological circumstances. The second limitation refers to the time period considered. Three years is not a long time compared to some other studies. Hence, some of the relationships analyzed might vary if we had considered longer or shorter periods.

In conclusion, we believe it is necessary to continue investigating how entrepreneurial firms achieve and sustain high growth in different contexts. Doing so will allow entrepreneurial firms to better identify what they need to grow and improve their chances of long-term survival.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Leitch, C.; Hill, F.; Neergaard, H. Entrepreneurial and business growth and the quest for a “comprehensive theory”: Tilting at windmills? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Temouri, Y. High-growth firms and productivity: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A. The Growth of Firms; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, B.A.; McDougall, P.P.; Audretsch, D.B. New venture growth: A review and extension. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 926–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, A.; Wiklund, J. Advancing firm growth research: A focus on growth mode instead of growth rate. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Building an integrative model of small business growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Krafft, J.; Quartaro, F. High-growth firms and technological knowledge: Do gazelles follow exploration or exploitation strategies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2014, 23, 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. High Growth Firms in Scotland; Research Report; Scottish Enterprise: Glasgow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parsley, C.; Halabisky, D. Profile of growth firms: A summary of Industry Canada Research, Industry Canada. Small Bus. Res. Stat. Rep. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daunfeldt, S.-O.; Elert, N.; Johansson, D. Are high-growth firms overrepresented in high-tech industries? Ind. Corp. Chang. 2016, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F.; Davidsson, P.; Gartner, W. Arriving at the high-growth firm. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls-Nixon, C.L. Rapid Growth and High Performance: The Entrepreneur’s ‘Impossible Dream? ’ Acad. Manag. Exec. 2005, 19, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzl, W. Persistence, Survival, and Growth: A Closer Look at 20 Years of Fast-Growing Firms in Austria. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2014, 23, 199–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; Frankish, J.; Roberts, R.G.; Storey, D.J. Growth Paths and Survival Chances: An Application of Gambler’s Ruin Theory. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Mawson, S.; Mason, C. Myth-busting and entrepreneurship policy: The case of high growth firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 414–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Wiklund, J. Conceptual and empirical challenges in the study of firm growth. In The Blackwell Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Sexton, D.L., Landström, H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Coad, A.; Daunfeldt, S.-O.; Hölzl, W.; Johansson, D.; Nightingale, P. High-growth firms: Introduction to the special section. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2014, 23, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, R.; Wennberg, K.; McKelvie, A. The Strategic Management of High-growth Firms: A Review and Theoretical Conceptualization. Long Range Plan. 2016, 50, 431–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrekson, M.; Johansson, D. Gazelles as Job Creators: A Survey and Interpretation of the Evidence. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 35, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Stigliani, I. Entrepreneurship and growth. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, F.H.; Prasad, A.; Segarra, P. The Political Embeddedness of Entrepreneurship in Extreme Contexts: The Case of the West Bank. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 157, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A. You can’t go home again: And other psychoanalytic lessons from crossing a neo-colonial border. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwan, U.S. Entrepreneurship and the prospects of development in the West Bank. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1989, 1, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, H.T.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Avolio, B.J.; Cavaretta, F.L. A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusay, A.A. Entrepreneurship from an Islamic perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izraeli, D. Business ethics in the Middle East. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, T.A.; Prasad, A. Entrepreneurship amid concurrent institutional constraints in less developed countries. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 934–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, M.; Hamilton, R.T. Small business growth: Recent evidence and new directions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2007, 13, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ahlstrom, D.; Obloj, K. Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goedhuys, M.; Sleuwaegen, L. High-growth entrepreneurial firms in Africa: A quantile regression approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 34, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Parsons, W.; Tracy, S. High-Impact Firms: Gazelles Revisited; Office of Advocacy of the US Small Business Administration (SBA): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schreyer, P. High-Growth Firms and Employment, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garnsey, E.; Stam, E.; Heffernan, P. New Firm Growth: Exploring Processes and Paths. Ind. Innov. 2006, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, L.; Arnold, R. New Zealand Firm Growth as Change in Turnover; Ministry of Economic Development: Wellington, NZ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daunfeldt, S.-O.; Halvarsson, D. Are high-growth firms one-hit wonders? Evidence from Sweden. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 44, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, M.; Cefis, E.; Frenken, K. On the existence of persistently outperforming firms. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2014, 23, 997–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, S.; Bottazzi, G.; Tamagni, F. What does (not) characterize persistent corporate high-growth? Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 48, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschella, D.; Tamagni, F.; Yu, X. Persistent highgrowth firms in China’s manufacturing. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; Daunfeldt, S.O.; Halvarsson, D. Bursting into life: Firm growth and growth persistence by age. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 50, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Coad, A. High-growth firms: Stylized facts and conflicting results. In Entrepreneurial Growth: Individual, Firm, and Region; Corbett, A.C., Katz, J.A., McKelvie, A., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2015; Volume 17187–17230. [Google Scholar]

- Daunfeldt, S.-O.; Elert, N.; Johansson, D. The economic contribution of high-growth firms: Do policy implications depend on the choice of growth indicator? J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2014, 14, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. What holds back high-growth firms? Evidence from UK SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyadike-Danes, M.; Hart, M.; Du, J. Firm Dynamics and Job Creation in the United Kingdom: 1998–2013. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F. Measuring growth: Methodological considerations and empirical results. In Entrepreneurship and SME Research: On Its Way to the Next Millennium; Donckels, R., Miettinen, A., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 1997; pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.; Wiklund, J. Are we comparing apples with apples or apples with oranges? Appropriateness of knowledge accumulation across growth studies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L.; Naldi, L.; Melin, L. ‘Business Growth’—Do Practitioners and Scholars Really Talk about the Same Thing? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisational for Economic Co-operation and Development). Measuring Entrepreneurship: A Digest of Indicators; OECD-Eurostat Entrepreneurship Indicators Program, Organisational for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coad, A. A Closer Look at Serial Growth Rate Correlation. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2007, 31, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, J.; Lichtenstein, B. A Terminal Assessment of Stages Theory: Introducing a Dynamic States Approach to Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 317–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; Srhoj, S. Catching gazelles with a lasso: Big data techniques for the prediction of high-growth firms. Small Business Economics. 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Bruneel, J.; Wright, M. Explaining growth paths of young technology-based firms: Structuring resource portfolios in different competitive environments. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D.; Rosa, P. The growth of business groups by habitual entrepreneurs: The role of entrepreneurial teams. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Aspiring for, and achieving growth: The moderating role of resources and opportunities. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1919–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. West Bank and Gaza, Local Government Performance Assessment; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, F. A Quantitative Analysis of the Characteristics of Rapid-growth Firms and Their Entrepreneurs in China. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, M.; Hamilton, R.T. Characterizing High-growth Firms in New Zealand. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2013, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, S.; Hamilton, R.T. High-Growth Firms in New Zealand: Superstars or Shooting Stars? Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 35, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, B.A.; Desai, S. Institutional Drivers of High-growth Firms: Country-level Evidence from 26 Transition Countries. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Technique, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K. Grounded Theory in Management Research; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, A.; Sohal, A.; Brown, A. Generative and case study research in quality management. Part I: Theoretical considerations. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1996, 13, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott, H. Writing Up Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research Methods, Series 20; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J.A.; Pett, T.L. Small-firm performance: Modeling the role of product and process improvements. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coff, R.W. Human capital, shared expertise, and the likelihood of impasse in corporate acquisitions. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).