Many major corporations still play things straight, but a significant and growing number of otherwise high-grade managers—CEOs you would be happy to have as spouses for your children or as trustees under your will—have come to the view that it’s OK to manipulate earnings to satisfy what they believe are Wall Street’s desires. —Warren Buffett

1. Introduction

Managers tend to report earnings towards some desired level of profit. However, the cost of earnings management is quite high. Manipulating earnings around IPO and SEO will lead to both short-term and long-term negative returns after their issuance [

1,

2]. In addition, firms with higher earnings management are not only more likely to deviate from the optimal investment level [

3,

4,

5] but are also more likely to be involved in lawsuits [

6,

7]. Furthermore, managers can even extract wealth from shareholders by using earnings manipulation [

8]. Therefore, preventing or mitigating earnings manipulation is an important task for shareholders, investors, and regulators.

The prior literature finds a negative relation between institutional investors and earnings management. However, there are two possible underlying mechanisms to explain this negative relationship between institutional ownership and earnings management: (1) institutions drive down earnings management through their monitoring role; (2) institutions prefer firms with lower earnings management when they make investment decisions. Both hypotheses can lead to a negative relation between institutional ownership and earnings management, but prior literature fails to disentangle which channel it is, since it is difficult to show that institutions drive earnings management because institutions may simultaneously choose stocks based on corporate earnings management. In other words, this relationship may be endogenous. In this paper, we explore whether the negative relation is due to the monitoring effect of institutional investors or the preference of institutional investors.

First, we use the Russell 1000 and 2000 indices reconstruction to obtain an exogenous variation in institutional ownership. Russell Investments ranks all U.S. firms based on their market capitalization on the last trading day in May each year; then, the first 1000 firms are included in the Russell 1000 index, while the next 2000 firms fall in the Russell 2000 index. Firms around the 1000th rank have very close market capitalization; however, since firms cannot control small variations in market capitalization, index assignment near the threshold is as good as random. Because of the value weighting system of the Russell indices and the dollar amount of funds tracking the two indices, the top firms in the Russell 2000 index receive a greater dollar amount from institutional investors compared to the bottom firms in the Russell 1000 index [

9]. This random assignment of the Russell 2000 index around the threshold leads to an exogenous increase in institutional ownership.

Currently, a growing body of literature uses the Russell 1000/2000 reconstitution event as an identification strategy to investigate corporate finance and asset pricing questions. Papers have exploited the Russell 1000/2000 index reconstruction to analyze the price effect of stock supply and demand [

9], the association between institutional holding and payout policy [

10], management disclosure [

11], acquisition and CEO power [

12], monitoring incentives [

13], and passive investor effect on firm governance [

14,

15]. A hurdle in implementing this identification strategy is the fact that the market capitalization that Russell uses to rank stocks in May is not publicly available. As a result, many studies use the actual assignment instead of market capitalization rank as the instrument to capture the change in institutional ownership, which may lead to selection bias [

16]. To mitigate this concern, rather than using the actual assignment, we use firms switching from one index to the other as the instruments for institutional holdings [

12]. As a result, firms jumping from the bottom Russell 1000 to the top Russell 2000 obtain more institutional holdings, and firms jumping from the top Russell 2000 to the bottom Russell 1000 have fewer institutional holdings. By applying this index reconstruction setting, we can test the causality between institutional holdings and earnings management. Our results show that higher institutional holding does not lead to lower earnings management.

Then, we test whether it is institutions’ preferences that lead to the negative correlation. We develop a measure of institutional preference on firms’ earnings management based on Kempf, Manconi, and Spalt [

17]. After adding this preference measure into the baseline regression, the negative effect between institutional holding and earnings management disappears, confirming that in the baseline regression, the negative relationship indeed captures institutions’ preferences rather than the monitoring effect. In addition, we find that higher earnings management leads to lower future institutional holdings; this effect is mitigated after the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in 2002, when there was an improvement in accounting quality. This result shows that better accounting quality could mitigate institutional investors’ concern over earnings management and lead to higher institutional holdings, which is consistent with the preference hypothesis. We further use firms that just beat the EPS forecast as an instrument for earnings management and find that institutional holding significantly decreases for firms with higher earnings management. Finally, we show that firms with higher earnings management have lowers institutional holdings and lower stock returns. This is evidence that institutions take earnings management into account when making investment decision and benefit from this strategy.

Our study contributes to the extant literature as follows. First, we provide new evidence on the literature of institutional investors and earnings management. Our study shows that the negative relationship between institutional holdings and earnings management is driven by institutional investors’ preference of firms with low earnings management, not the external monitoring role of institutional investors. Second, according to our best knowledge, this is the first paper that applies the instrumental variable setting to disentangle the causal relationship between institutional holding and earnings management, which provide further exploration on the related topics.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review and hypothesis development.

Section 3 introduces data and methodology.

Section 4 discusses the empirical results, and

Section 5 provides additional analysis.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

From the prior literature, it is shown that institutional investors can exert influence on firm governance, through either their voice (direct intervention), or the threat of exit (indirect intervention). In the direct intervention, institutions can influence firm governance and operations by using their voting rights [

18,

19]. In the indirect intervention, institutions can sell their holdings if the firm does not perform well, thus exerting a threat of exit [

20,

21,

22].

Based on these monitoring hypotheses, Chung, Firth, and Kim [

23] find that the presence of large institutional shareholdings inhibits managers from increasing or decreasing reported profits towards their desired level or range of profit. Cornett, Marcus, and Tehranian [

24] also find that earnings management is lower when there is more monitoring of management discretion from sources such as institutional ownership of shares and institutional representation on the board.

However, existing literature shows that institutional investors have their own preferences while making investment decisions. Bennett, Sias, and Starks [

25] shows that institutional investors have a preference on corporate capitalization. Petersen and Vredenburg [

26] documents that the corporate social responsibility is an important factor for institutional investors’ portfolio. Schnatterly and Johnson [

27] finds that institutional investors prefer to invest in firms with greater board independence.

Therefore, the negative relation between institutional ownership and earnings management may not be caused by the monitoring effect of institutional ownership but caused by the institutional investors’ preference.

Hypothesis: Institutional investors do not drive down corporate earnings management through their monitoring role; instead, institutional investors invest in firms with lower earnings management.

Our study differs from the existing literature in that we disentangle the causal relation between institutional ownership and earnings management, which providing regulator and investors a better understanding on the role of institutional investors.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample

In June of each year, FTSE Russell ranks all U.S. firms based on their market capitalizations on the last trading day in May. The market capitalization is calculated by multiplying the closing price on the last trading day in May and the number of total common shares outstanding. When there are more than two classes of shares, Russell uses the share price of the class with the largest number of floating shares. Then, the largest 1000 firms constitute the Russell 1000 index, and the subsequent 2000 firms go to the Russell 2000 index. At the end of June, Russell Investments publishes the new index list and index weight. Other than certain corporate events such as corporate mergers or delisting, firms remain in the index until June of the following year.

Our sample includes firms in the Russell 1000 index and Russell 2000 index from 1995 to 2015. We obtain the index constitution data from Bloomberg, which include firm ID, firm name, year, index membership, and market capitalization. Then, we merge it with firm-level accounting data from Compustat, institutional ownership data from Thomson Reuters 13F filing, analyst forecast data from I/B/E/S, and security market data from CRSP through firm ID and year. The institutional investor types are from Bushee and Noe [

28] and Bushee [

29].

3.2. Measure of Earnings Management

We use the performance-matched discretionary accruals measure of Kothari, Leone, and Wasley [

30] as the proxy for earnings management. To construct this measure, we first estimate the following cross-sectional regression of each fiscal year in each industry based on the first two digits SIC industry code:

where

i indicates the firm and

t indicates the fiscal year. Total accruals (TA) are defined as earnings before extraordinary items and discontinued operations minus operation cash flow for fiscal year

t.

is total assets at the end of year

t − 1,

is the change in sales revenue from year

t − 1 to year

t, and

PPEt is the gross value of property, plant, and equipment at the end of year

t.

Next, we use the coefficient estimated in Equation (1) to estimate the expected normal accruals:

The change in accounts receivable

is subtracted from the change in sales revenue as credit sales also provide a potential opportunity for accounting distortion [

31]. Firm-specific discretional actual is the actual total accruals minus predicted normal accruals. Then, we adjust the estimated discretionary accruals for performance. We match each sample firm with the firm from the same fiscal year-industry that has the closest return on assets as the given firm. The performance-matched discretionary accruals, denoted as DAmatch, are then calculated as the firm-specific discretionary accruals minus the discretionary accruals of the matched firm. Since both positive and negative values indicate earnings manipulation, we take the absolute value of DAmatch and treat it as earnings management measure, noted as |DAmatch|.

Table 1 reports the summary statistics for firms in the Russell 1000 index and the Russell 2000 index. We see that institutional investors on average hold 68% of firms’ total shares outstanding. Based on Bushee and Noe’s investor classifications, institutional investors are divided into dedicated investors (long horizon and concentrated portfolio), quasi-indexers (long horizon and diversified portfolio), and transient investors (short horizon and diversified portfolio). Most institutional holdings belong to quasi-indexers (QIX), which account for 46% of firm total outstanding shares. The average holding of the transient investors (TRA) is around 16%, while that of the dedicated investors (DED) is around 6%. The mean (median) of our measure of earnings management |DAmatch| is around 0.15 (0.08).

Other variables are firm characteristics controls. Size is the natural logarithm of a firm’s total assets. MB is the market value of equity to book value of equity. Leverage measures capital structure for firms’ financing decisions, which is calculated as long-term debt (DLTT) plus debt in current liabilities (DLC) scaled by the sum of long-term debt, debt in current liabilities, and total shareholders’ equity (SEQ) at the end of the year. If the value is high, it means more financing from debt; if the value is low, it means more financing from equity. OIBDP is operating income before depreciation (OIBDP) during year

t scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year, which measures how much profit a firm can generate for one dollar of assets. The average profitability for the sample is around 12%. Firm characteristics variables are described in detail in the

Appendix A.

3.3. Index Reconstruction Design to Test Monitoring Hypothesis

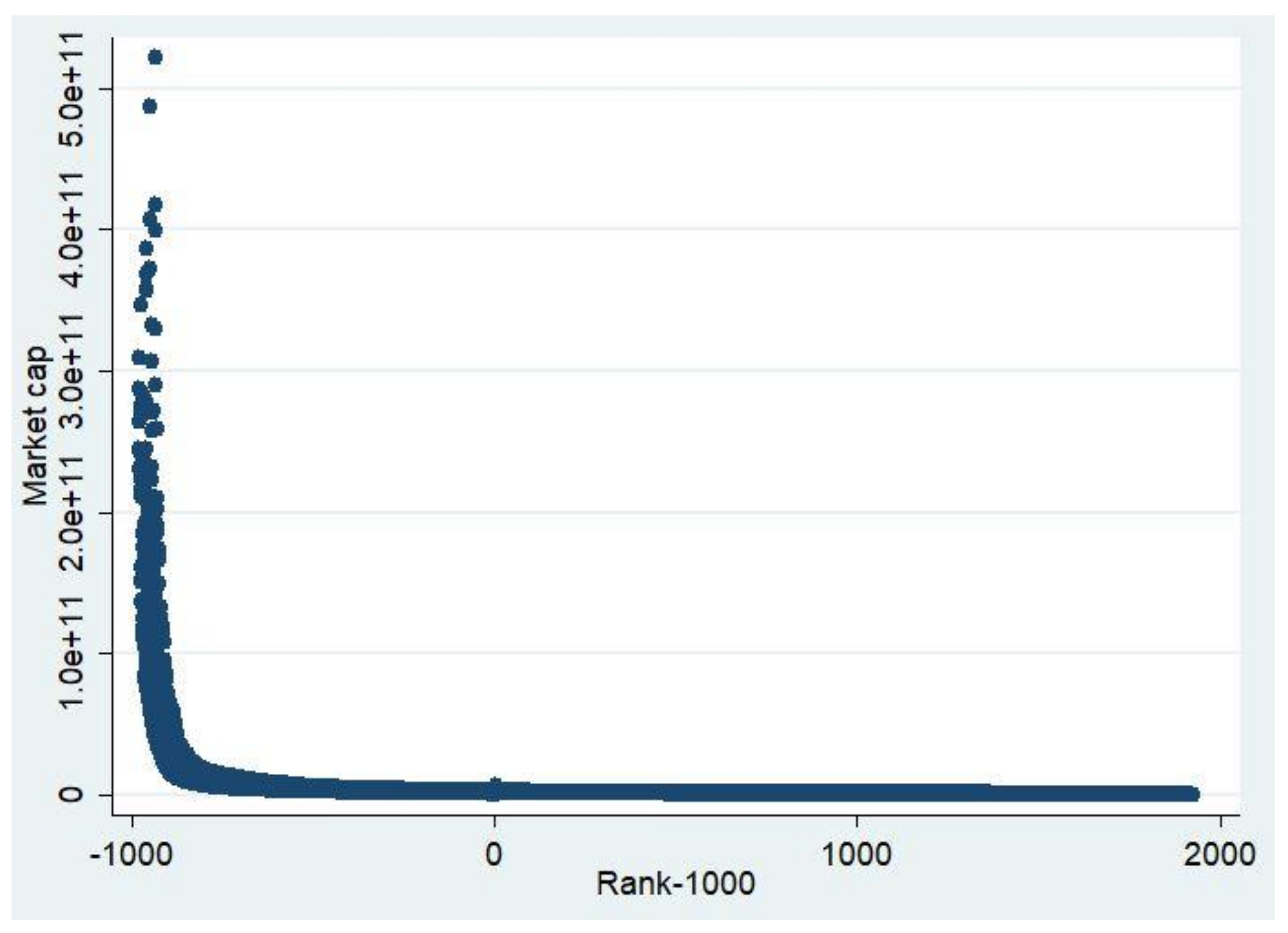

The monitoring hypothesis suggests that institutional investors drive down earnings management after they become shareholders of the firms. We employ the instrumental variable design around the cutoff of Russell 1000 index and Russell 2000 index to test the monitoring hypothesis. As

Figure 1 shows, firms around the threshold have comparable market capitalization; since firms cannot control small variations in market capitalization rank on a determined day, the assignment to different indexes is as good as random around the cutoff. In addition, the Russell Indices are value weighted, so firms at the top of the Russell 2000 index receive much more weight because they are the largest firms in the index than firms at the bottom of the Russell 1000 index, which are the smallest firms in that index.

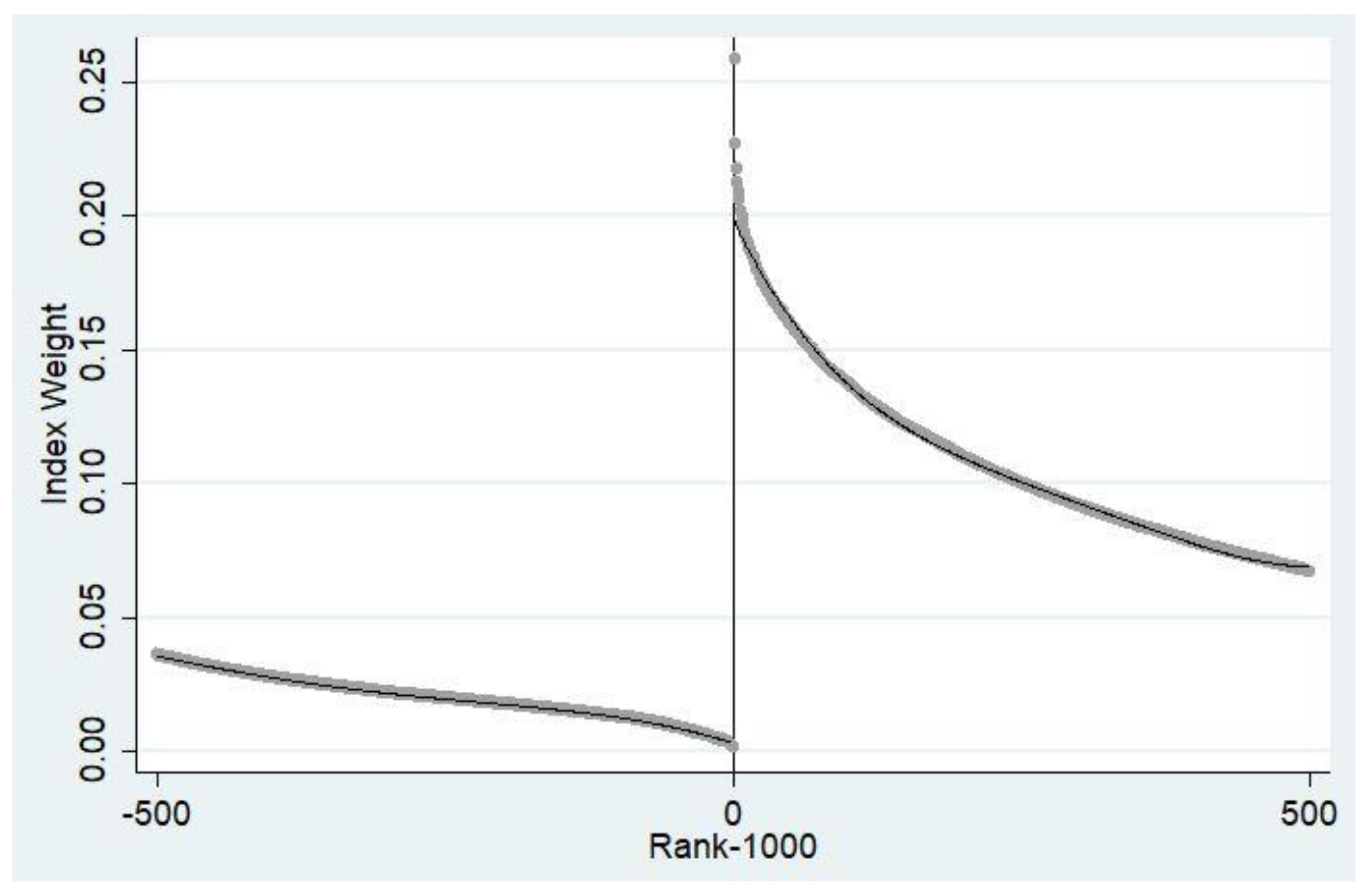

Figure 2 plots the index weight and the market capitalization rank for firms in the Russell 1000 index and the Russell 2000 index around 500 bandwidths from the cutoff point. We can see top firms in the Russell 2000 index (rank from 0 to 500) have much higher weights compared to the bottom firms in the Russell 1000 index (rank from −500 to 0). The closer to the cutoff points, the difference becomes even larger.

The Russell indices attract a large amount of investments. According to Russell Investments’ 2008 U.S. Equity Indices: Institutional Benchmark Survey, the number of products benchmarked to the Russell 2000 is about two thirds compared to the number benchmarked to the S&P 500; the dollar amount is about one seventh compared to that of the S&P 500; and the ratios are increasing over time. Since the relative weights of the top Russell 2000 firms are about 10 times the relative weights of the bottom Russell 1000 firms, although more dollars are invested in the Russell 1000, the top firms in the Russell 2000 receive a greater dollar amount compared to the bottom Russell 1000 firms. Therefore, the institutional holding for top firms in the Russell 2000 is correspondingly much higher than for bottom firms in the Russell 1000.

Since there is an exogenous variation in institutional holdings around the index cutoff, we use the switching between two indices as the instrument for institutional holdings. The benefit to apply this method is that we can extend the sample range beyond the banding policy, which is from the year 2007. After 2007, Russell introduced a “banding” rule to maintain consistency for index constitution. Under this new rule, only if a firm’s market capitalization change is big enough can it switch to the other index; otherwise, the firm will stay in its current index. To be more specific, firms are ranked in a descending order based on their end of May market caps, and a cumulative market cap is calculated for each firm. Then, the cumulative market cap is divided by total market cap of all Russell 3000E firms to get the market cap ratio for each firm. Based on this market cap ratio, a firm will jump into the other index only if its market cap ratio is more than ±2.5% away compared to the 1000th firm market cap ratio. We can tell this banding rule reduces the turnover for index constitution.

To identify the causal relationship between institutional ownership and earnings management, we implement the 2SLS model following Schmidt and Fahlenbrach [

12]:

The first stage regression (Equation (3)) is based on instrument variable design. We use switching between indexes: and as the instrument for institutional ownership. is an indicator that a firm jumps from the Russell 1000 to the Russell 2000, and is a dummy variable which equals one when a firm switches from the Russell 2000 to the Russell 1000. The underlying assumption is for firms switching from the Russell 1000 to the Russell 2000 or from the Russell 2000 to the Russell 1000, there is an exogenous variation in institutional holdings. Hence, switching between the two indices is correlated with institutional holdings but has no direct relation with the main dependent variable, earnings management. We expect a positive sign for firms switching from the Russell 1000 to the Russell 2000 and a negative sign for firms switching from the Russell 2000 to the Russell 1000. is a function based on a firm’s end of May market capitalization rank and its higher polynomial orders, to account for the distance to index threshold. FloatAdj is the proxy for Russell index float adjustment, computed as the difference between end of May market capitalization rank and the actual rank assigned by Russell Investments in June. By including this variable, we also control the variation in index weight caused by Russell Investments’ adjustment on float shares. X stands for firm characteristics, which include size, market-to-book, OIBDP, and leverage.

In the second stage regression (Equation (4)), we use the predicted IO variable obtained from the first stage to test its causal effect on earnings management. The earnings management measure |DAmatch| is from current year July to the next year June, since it may take time for institutions to exert their influence, as well as to mitigate the rebalance issue in the subsequent year. We also control for firm characteristics, Rank and FloatAdj, just as with the first stage’s controls. Both stages include year and industry fixed effect, and the standard errors are clustered by firm.

Based on our hypothesis of institutional investors’ preference, we expect the coefficient of the predicted IO should not be significant.

3.4. Tests for the Preference Hypothesis

To test the preference hypothesis, we develop a measure for institutions’ preferences on earnings management based on the approach from Kempf, Manconi, and Spalt [

17]. Kempf et al. develop a way to measure firm level shareholder distraction. We apply a similar method to measure firm-level institutional preference for earnings management. Institutions have investments in many firms, and each firm has many institutional holdings. We calculate the measure in two steps. In the first step, for each institution, we calculate the dollar-weighted average of the earnings management level of the firms in its holdings as follows:

where

refers to firm

f’s earnings management level in year

t.

is the set of all stocks held by institution

j at year

t, and

is the dollar amount of institution

j’s funding allocated to stocks of firm

f. Based on this calculation, we have a measure of institution-level earnings management preferences.

Then, to obtain the firm level institutional investor preference for earnings management, for each firm, we calculate the dollar-weighted earnings management preference for each institution that has holdings of this firm. This measure is the institution’s preference for firm earnings management:

where

is the institution

j’s preference on earnings management in year

t as defined in Equation (5).

is the set of all institutional investors who invest in firm

f at year

t and

is the dollar amount of institution

j’s funding allocated to stocks of firm

f. This firm-level aggregate preference is referred to as the average institutional preference for earnings management level.

After replicating prior literature and demonstrating the relationship between institutional holdings and earnings management, we add the preference measure into the baseline regression to see whether the negative effect between institutional investor holdings and earnings management still holds. If this effect is no longer significant after the inclusion of preference measures, then it indicates that the prior finding may only capture institutional investors’ preferences.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

To test whether the Russell sample is comparable to other studies, we first run the panel regression to test the relationship between earnings management and institutional holdings. We regress earnings management on institutional ownership and other firm characteristics, in addition to year and firm fixed effects.

Table 2 reports the panel regression results. Column 1 shows the results based on the total institutional ownership and column 2 separate institutional investors into dedicated (DED), quasi-indexer (QIX), and transient investors (TRA). We can find there is a significant negative relationship between institutional ownership and earnings management, which indicate that the Russell sample is in line with results reported in the prior literature.

4.2. Results for Monitoring Hypothesis

As the sharp difference in index weight leads to an exogenous variation in institutional ownership around the Russell 1000/2000 index cutoff point, we try to identify whether the increase in institutional ownership can lead to a change in corporate earnings management.

Table 3 shows the 2SLS regression results based on the instrument variable design. We run the 2SLS regression as described in Equations (3) and (4). The first two columns are for larger bandwidth ±750 and ±500, and the last two columns are for smaller bandwidth ±100 and ±50. The first stage uses firm switching into the other index, along with other control variables described in Equation (3), to predict institutional holdings. We can see that there is a significant relation between switching indicators and institutional ownership: firms switching from the Russell 1000 to the Russell 2000 gain higher institutional holdings and firms switching from the Russell 2000 to the Russell 1000 have fewer institutional holdings. Therefore, switching from one index to the other is a valid instrument to predict institutional ownership.

In the second stage, we use the predicted IO, which is obtained from the first stage to test the causal effect on earnings management. Consistent with our hypothesis, we find none of the coefficients for predicted IO are significant, which means that the increased IO does not have any significant effect on earnings management. We also try higher order polynomials and longer periods after the index rebalance and still get same results. This evidence shows that an exogenous increase in institutional ownership does not affect earnings management. Therefore, the negative relation between institutional holdings and earnings management found in the prior literature cannot be explained by the monitoring hypothesis.

Some studies that exploit the Russell index reconstruction setting use different methodologies. For example, Appel, Gormley, and Keim [

14,

15] use market capitalization instead of rank in the 2SLS regression, and Crane et al. [

10] and Appel et al. [

14,

15] use actual assignment as the instrument for institutional holdings. We also apply their methodologies, and the different methodologies do not affect our results. Therefore, our finding is robust to different specifications.

4.3. Results for the Preference Hypothesis

In this part, we test the other channel: whether institutional investors prefer firms with lower earnings management.

4.3.1. Measure of Institutional Investor Preference

We first develop a measure for institutions’ preferences on earnings management. Then we add this preference measures into the baseline regression to test whether the negative relationship between institutional holdings and earnings management still holds. If the magnitude becomes insignificant, it suggests that the prior negative correlation indeed captures institutional investor’s preference.

Table 4 shows the results after adding preference measures.

Preference is the firm-level aggregate institutional preference following Kempf, Manconi, and Spalt [

17]. Since institutions make investment decisions before they become shareholders, it should be based on their prior year preference. Therefore, we use the prior year preference in the regression. The first column is the baseline regression from which we can see a negative correlation between institutional ownership and firm earnings management. In column 2, after the addition of preference measures, the significance of institutional ownership disappears, and the magnitude becomes close to zero. Therefore, the baseline negative correlation between institutional holdings and earnings management essentially captures institutions’ preferences, not the monitoring effect. Consistent with our hypothesis, those results indicate that it is not institutions’ monitoring effect that influences firm earnings management level; instead, institutions choose firms with lower earnings management.

4.3.2. Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002

To further test the preference hypothesis, we regress the forward year institutional holdings on the current year firm earnings management. As shown in

Table 5 column 1, the coefficient of the earnings management is negative, indicating that a high earnings management level is correlated with low institutional holdings in the forward year. To mitigate the endogenous concern, we apply the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in 2002 as an instrument for the improvement in financial disclosure. The SOX Act mandates strict reforms to improve financial disclosures from corporations and to prevent accounting fraud. Cohen, Dey, and Lys [

32] document that accrual-based earnings management increased steadily from 1987 until the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002, followed by a significant decline after the passage of SOX. Therefore, if earnings management is a serious concern for institutional investors, investors’ concern should be mitigated after the SOX Act. If the preference hypothesis is true, after we add the interaction term between SOX and earnings management into the regression, the coefficient should be positive, which means the negative correlation between earnings management and institutional holdings could be mitigated.

In

Table 5 column 2, we add SOX and the interaction term between SOX and earnings management into the baseline regression. We can find the interaction term is positively significant, which means that the negative effect is lightened after the passage of the SOX Act. From this evidence, we can see that the improvement in accounting quality can alleviate invertors’ concern and attract more institutional holdings, which further supports the preference hypothesis.

4.3.3. Applying EPS Beat as the Instrument of Earnings Management

Burgstahler and Dichev [

33] and Jacob and Jorgensen [

34] document a discontinuity around zero between the difference of reported earnings and forecasted earnings by analysts. They find a disproportionately low frequency of values just below zero, and a disproportionately high frequency of values just above zero. Burgstahler and Eames [

35] and Bennett et al. [

36] also find that firms manipulate earnings to meet analysts’ forecasts.

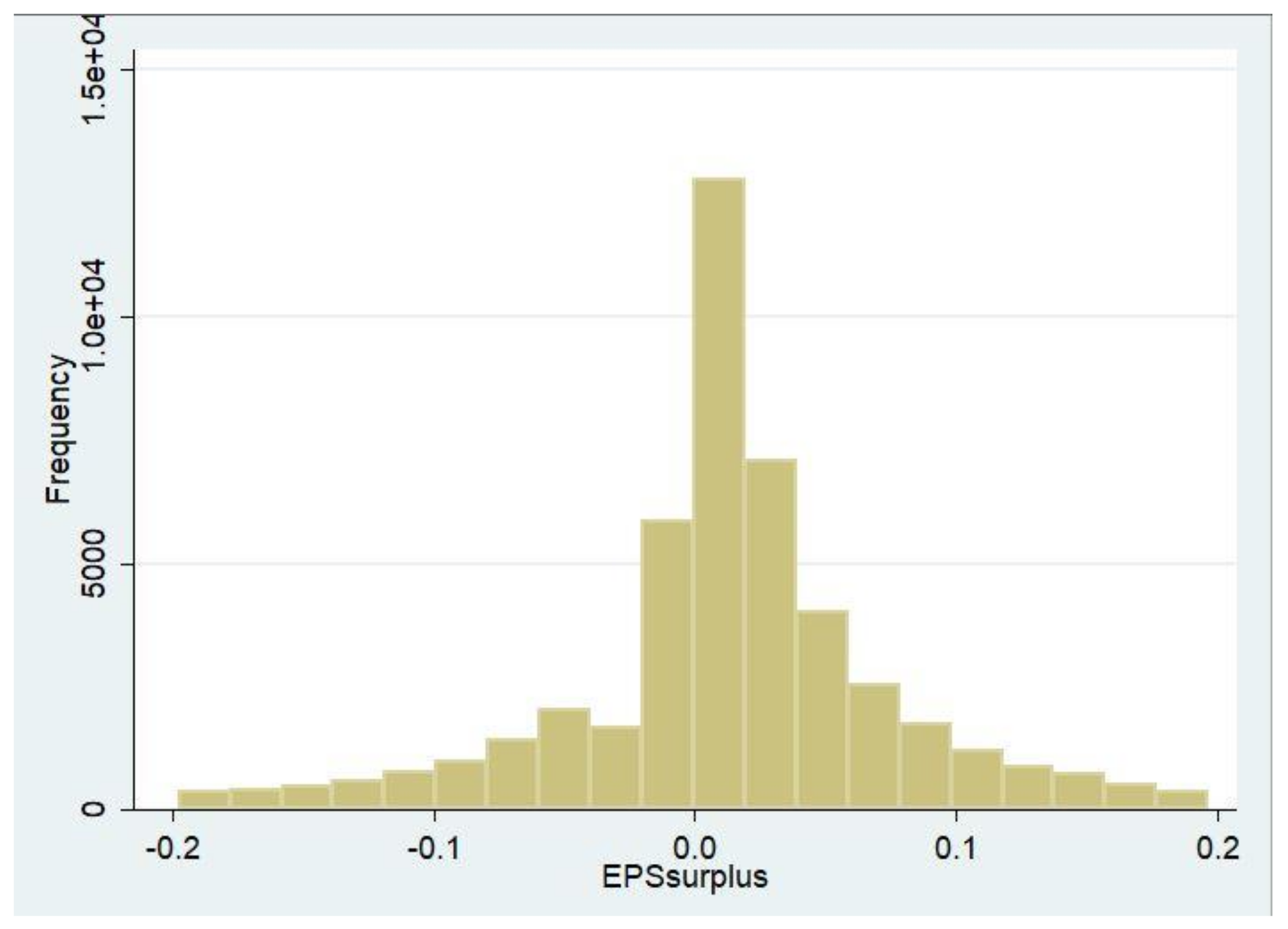

Figure 3 confirms their argument. The figure plots the frequency with which firms beat analysts’ EPS forecasts. We take the difference between actual earnings per share (EPS) and the median of analysts’ forecasts to measure the

EPS surplus. If it is a positive number, it means the firm beats analysts’ forecasts; if it is a negative number, it means the firm misses analysts’ forecasts. If firms do not manipulate accruals, we should find that the frequency with which firms just beat EPS forecasts is close to the frequency with which firms just fall short of forecasts. However, from

Figure 3, we find that there is much higher frequency of firms that just beat analysts’ forecasts compared to firms who just fall short. Therefore, there is a fundamental reason to expect that firms that just beat EPS forecasts use more earnings management compared to firms that just fall short of forecasts. Hence, whether the firm beats analysts’ forecasts (

Beat EPS) can be an instrument variable for earnings management. In addition, we can use this instrument to test whether a change in earnings management impact future institutional holdings.

To be more specific, we apply the 2SLS as follows:

where

Beat EPS is a dummy variable that indicates whether a firm’s actual

EPS beats analysts’ forecasts. We calculate the difference between the actual

EPS and the median of the analysts’ forecast

EPS. If the difference is equal to or bigger than zero, the dummy equals one; otherwise, the dummy equals zero. Then, we rank all firms based on how much they beat or fall short of analysts’ forecasts within beat

EPS (or fall short of

EPS) to capture the distance to the beat

EPS threshold. The interaction term between

Beat EPS and

rank captures the shape of regression for firms that beat or miss the

EPS target.

X is the control variable for firm characteristics, which includes size, market-to-book, OIBDP, and leverage. In the second stage, we use the predicted earnings management to capture the effect between earnings management and the change in institutional holdings. We also add the same interaction terms and control variables as in the first stage. For institutional holdings, we use current year, forward one-year, and the difference between forward one-year and current year.

Table 6 shows the results of instrumented earnings management effect on institutional holdings. The dependent variable for columns 1 and 2 is the current year institutional holdings while for columns 3 and 4 it is the forward one-year institutional holdings, and for column 5 and 6 it is the change between forward one-year holdings and current year holdings. In addition, columns 1, 3, and 5 are for firms whose actual EPS minus analyst forecast EPS are within ±2 cents, and columns 2, 4, and 6 are for firms whose actual EPS minus analyst forecast EPS are within ±5 cents. From the results, we can see that predicted earnings management has a negative impact on institutional holdings, both for the current year and forward one-year: higher corporate earnings management leads to lower institutional investments. When the dependent variable is replaced as the change in institutional ownership, both bandwidths also have negative changes. The results show that when there is an exogenous increase in earnings management, institutional investors will pull back their investments promptly. These data further support that institutional investors prefer firms with lower earning management: When the firms exogenously increase their earnings management, institutions will decrease their holdings shortly.

5. Additional Analysis

In this section, we try to explore whether firms with lower earnings management attract more institutional holdings, and if institutional investors invest in firms with lower earnings management, whether they benefit from this strategy.

First, we divide firms into deciles based on their earnings management level in each year; then, we calculate the average of institutional ownership and annual stock returns in each group. For stock returns, we obtain monthly return data from CRSP and compound it to annual returns for each firm.

In

Table 7, we find that firms with the lowest level of earnings management have institutional holding around 65.9% and average annual return of 11.9%. Firms with the highest level of earnings management have institutional holding around 59.1% and average annual return of 8.9%. The difference in institutional holding is about 6.8%, and the difference in stock return is about 3.0% between these two groups. Both are statistically and economically significant.

From this additional evidence, we can see that firms with lower earnings management attract more institutional holdings, and lower earnings management is associated with higher returns. This result further supports the preference hypothesis: institutions invest in firms with lower earnings management, and they benefit from this investment strategy.

6. Conclusions

Prior literature shows that there is a negative correlation between institutional holdings and earnings management and claims that institutions play a monitoring role and thus drive down earnings management. However, institutions may endogenously choose to invest in firms with lower earnings management. In this paper, we try to disentangle this issue by applying index reconstruction and beat analyst EPS forecast design.

In contrast to prior findings, we find that when there is an increase in institutional holdings, institutional investors have no direct impact on firms’ earnings management. This indicates that the negative relationship is not caused by institutions’ monitoring roles.

To test whether institutions choose firms with lower earnings management, we developed a measure to capture institutional preference on firm earnings management level. After adding the preference measure into the baseline regression, we find that the negative effect disappears, which confirms that the prior literature’s finding captures institutional preference. We also use the passage of the SOX Act as an instrument for the improvement in accounting quality to test earnings management’s effect on institutional holdings. Furthermore, we apply whether a firm beats EPS forecast as an instrument for earnings management and find that higher earnings management reduces institutional holding in the subsequent year. Finally, we find that firms with lower earnings management levels attract more institutional investments and have higher stock returns. This further supports the preference hypothesis and provides a possible explanation for this investment strategy. All the above evidence show that it is institutional investors’ preferences, not their monitoring roles, that lead to the negative relationship between institutional holdings and earnings management.

To our best knowledge, this is the first paper to disentangle the endogeneity issue between institutional holding and corporate earnings management. The exogenous change in institutional holdings for Russell index reconstitution and the disproportional frequency with which firms beat their goals provide us with possible mechanisms to explore the causality. The limitation is that the change in institutional holdings of firms switching between the Russell indexes is marginal, which may not capture the effect of extreme change in institutional holding.

The instrumental variable setting of Russell Index and beating forecasted EPS can cultivate potential topics in the study of institutional investor’s impacts on corporate governance and studies on behavioral finance such as investors’ reaction to changes of earnings management.