1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is shaking the world economy that has placed small businesses under colossal pressure to survive, challenging them to respond effectively to the crisis. In many countries, the essential lockdowns trying to tackle the coronavirus have led to the most significant quarterly drop in economic activity since 1933 [

1]. Compared to other economic recessions, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the economic landscape on a considerably faster timeline in areas such as the move of activities to home-shoring and virtualization. In this turbulent market, small businesses worldwide can play a significant role in preventing mass unemployment, poverty, and income inequality since these companies are considered the backbone of any economy [

2]. Despite some recovery due to the massive governmental assistance, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown how major environmental jolts could be devastating for small businesses. They erode trust, damage company values, and reputation, threaten business objectives, and overwhelm managers by swiftly responding to shock [

3].

In the face of present and future crises in today’s turbulent world, thinking proactively about resilience seems to be the only option to survive. In any corporation, especially small organizations, the center of crisis management [

4] is to develop resilient strategies that confine economic loss and build resilience and capacity to survive and prosper [

5]. Even though small businesses seem to be vulnerable in crises due to their limited financial resource and weaker market positioning, they can take advantage of their small size to be more agile, adaptable, innovative, and resilient during challenging times [

6]. Established business models can be ineffective during this transboundary COVID-19 crisis, and as such, business succession can be rigorously disrupted. Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003) define resilience as a concept that is coupled with challenging situations threatening to jeopardize the fixed and rigid performance. In other words, resilience has been measured as the ability to bouncing back from adversity [

7].

Resilient organizations need to be prepared for environmental jolts [

8] to respond to adversity effectively with organizational capabilities as resilience sources [

9]. Hence, small businesses must consider the overarching effect of resilience on the environmental interaction of a small business, and analyze the macro-environmental factors (PESTEL: political, economic, sociocultural, technological, environmental, and legal) to successfully monitor the environment, foresee possible threats, and respond to disruptive challenges appropriately to sustain their competitive advantage. Congruent assimilation of resilience to a small business ecosystem requires a configuration model capable of distinguishing between domains and processes.

The concept of organizational resilience is built upon a foundation comprised of a few complementary fundamental elements. Employee-focused resilience has been considered one of four fundamental individual factors—efficacy, hope, optimism, and employee-focused resilience—that are associated with effective performance and individual/organizational resilience [

10]. Resilient organizational culture is another principal aspect of organizational resilience that enables employees and leaders to appropriately cope with environmental threats. Developing a resilient culture entails establishing a corporate culture that encourages trust, responsibility, and adaptability [

11]. A resilient culture promotes risk awareness, well-being awareness (physically and emotionally), lifelong learning, teamwork, adaptability, and flexibility [

12]. Small resilient organizations develop their strategy based on strategy games to improve the likelihood of success during unprecedented circumstances [

13]. Scenario planning based on probable future events is at the core of such a strategy-making process [

14]. Small businesses adopt strategic tools to continuously identify the relationships between future risks with detrimental consequences in avoiding risk cascading into a crisis.

All businesses, especially small businesses that are more vulnerable to uncertainty, need to develop a new adaptive structure that is highly adaptable to the changing needs to cope with this challenging circumstance. This type of structure is fluid and dynamic, streamlined, strategic fit, and has succession planning as an integral part of its organizational procedures. Last but not least organizational domain in resilience is an operation domain that needs to be agile and flexible [

15]. Since, upon crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, organizational business models and operations may alter [

16], businesses need a suitable organizational structure for a smooth implementation of resilient strategies.

This paper attempts to provide a unified approach that encompasses the inherent interrelationship of different organizational strategic development processes through an amalgamation of different models resulting from a multitude of studies about small business resilience. This paper proposes a strategic resilience framework for small businesses operating in post-COVID-19 or any other crisis by implementing Pattern Matching. The strategic resilience frameworkdemonstrates that a resilient organization aligns a resilient culture with its strategy through its operations and structures.

2. Literature Review

Small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) are major contributors to the world economy. SMBs, which are basically defined as companies with 500 or fewer employees [

17], play an essential role in shaping more than 90 percent of the private sector and creating 70 percent of all the world’s jobs [

18]. SMBs’ contribution plays a significant role in global economic growth [

19]. According to the OECD, they generate approximately 60% of value-added income in high-income countries [

20]. SMBs assist in reducing income inequality for minorities and shrinking poverty, especially in developing countries. These companies are also pivotal for local economies, creating employment opportunities, and sustaining local resources [

20]. SMBs constitute a significant value creation source by advancing economic inclusiveness for underrepresented groups [

20].

Despite the fact that SMBs are more flexible, agile, and more adaptable because of their smaller scale, they have less access to resources [

21] to fall back on during market volatility, creating further financial, network, and supply chain constraints. Therefore, SMBs count greatly on their exciting revenues and profits to survive [

22]. Due to their inherent nature, SMBs usually have a limited credit history, which ultimately leads to less access to finance. Additionally, not every small- or medium-sized company has the opportunity or resources to engage in the international market and bear various regulatory and administrative costs [

23]. These challenges make SMBs vulnerable when it comes to unprecedented circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 outbreak has exacerbated growing financial threats and has revealed hidden vulnerabilities for many small businesses.

When COVID-19 was officially announced as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020, future thinkers predicted one of the most significant and unprecedented shifts in the modern era interwoven with uncertainty for people’s future lives and businesses alike. According to Stephen Morrison and Anna Carroll, “Pandemics change history by transforming populations, societies, economies, standards, government, and governing structures” [

24]. Many studies, especially the Seven Revolutions Initiative assessment, which is continually updated with a 30 year time horizon, reveal that COVID-19 has brought a paradigm shift that will have major implications till 2050 [

25]. This assessment indicates that the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in the long term is unpredictable and most likely quite different than its near-term effect; therefore, the unevenness and unpredictability of COVID-19 represent the challenges ahead [

26].

The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMBs has been severely devastating, so that many businesses have ceased their operations during the lockdown. Studies reveal that 26% of SMBs closed from January to May 2020; this number is almost doubled to 50% in some developing countries such as Ireland and Bangladesh [

20]. Another OCED survey shows that nearly 62% of SMBs reported lower sales in the last months comparable to the corresponding period in 2019. Many small businesses operating in industries such as tourism, hospitality, hotels, and food services have been rigorously affected. For instance, almost 47% of SMBs offering services in hospitality and 54% of tourism agencies ceased their operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

27]. Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic depicts an external jolt of unparalleled consequence for SMBs, causing a significant decrease in their earnings and profits. Pedauga et al. (2021) predict an overall 43% drop in SMBs operating in Spain [

28]. Similarly, Diez et al. (2021) expect that the proportion of insolvent small- and medium-sized enterprises (i.e., SMBs with negative equity) may rise by six percentage points over 2020–2021 [

29]. McKinsey’s global empirical surveys (2020) indicate that between 25% and 36% of small businesses may have closed down permanently from the disruption in the first four months of the pandemic [

30].

These challenges are worse for small businesses [

31]. Even though small businesses take advantage of their learning capabilities through their agility, flexibility, and innovation [

12,

21,

32], due to their constrained resources and limited access to the global market, they are more vulnerable to crisis events. During the COVID-19 pandemic, almost 30% of small businesses were closed. A major survey conducted by Bartik et al. (2020) explored the impact of COVID-19 on 5800 small businesses [

33]. They found mass layoffs and closures, with the risk of increased closures due to the prolonged length of the crisis. This survey showed that the bureaucratic hassles and challenges in establishing eligibility and credibility for government aid create significant hurdles for small businesses regarding the effectiveness of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

SMEs need to develop proper strategic crisis planning [

34] in order to survive and recuperate from challenging occasions. Staw et al. (1981) introduced resilience for the first time and discussed how external threats could provoke rigid and fixed responses that might threaten the organization’s survival. Meyer (1982) introduced “Environmental Jolt” in resilience [

35] and how organizations develop adaptability in response to such threats. Looking at other resilience definitions, Legnick-Hall et al. (2011) define resilience as a corporation’s ability to effectively develop appropriate responses to engage in a transformative process to capitalize on disruptive shocks that potentially threaten business survival [

36]. Their definition of resilience has some common elements with organizational capacities such as agility, flexibility, and adaptability. Still, resilience is distinctive in its unique characteristic that includes a significant transformation of the corporation. This transformational approach embraces the idea that resilience should be a strategic initiative connected to the organizational competitive advantage. In other words, resilience should be allied with a corporate competitive advantage so that developing a resilient organization should become a strategic imperative. In another definition provided by Denyer (2017), resilience has been defined as a strategic objective designed to help a company survive and prosper [

37]. Denyer discusses that a highly resilient organization is more agile, flexible, adaptive, robust, and more competitive compare to less resilient organizations.

The temporality of resilience has been discussed by many scholars such as Williams et al. (2017), who believe that resilience does not occur in a particular ‘moment’ but is continually present. They detail that resilience is a process by which an organization develops and uses organizational capacity endowments to positively adjust to the environment and sustain functioning before, during, and following adversity. The two primary approaches of resilience, namely, characteristic and developmental perspectives, were defined by Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003). The characteristics perspective towards resilience emphasizes organizations’ inherent ability to recover from the crisis, while the developmental approach views resilience from a more ongoing process. Kuckertz et al. (2020) believe that some entrepreneurs seek new opportunities and build new trends for small businesses during crises [

38]. Small businesses have unique opportunities because of their diverse and robust knowledge to promote resilient market responsiveness.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper proposes a conceptual framework through a qualitative analysis of existing academic resources regarding strategic resilience for small businesses facing unprecedented times, such as COVID-19. Considering the exploratory nature of the current research undertaking, existing empirical research literature pertinent to this research’s topic is investigated towards the formulation of a suitable strategic resilience framework for small businesses. Amongst two main exploratory research methods, meaning the primary research and the secondary research method, the secondary research method is selected for this paper. Therefore, existing sources, including literature research and scholarly articles, are gathered and investigated.

Small businesses could be viewed from multiple interconnected perspectives. Hence, resilience would need to be examined from each perspective separately to develop a comprehensive strategic resilience framework. One of these primary aspects is the role of external factors or environmental jolts in organizational resilience. Environmental jolts were introduced by Meyer (1982) as the “transient perturbations whose occurrences are difficult to foresee and whose impacts on organizations are disruptive and potentially inimical”. Organizational strategic decisions, growth, and sustainability are inevitably influenced by environmental jolts [

39]. Due to environmental jolts, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncertainty of the future will be increased [

40,

41], and as such, the availability of resources will alter for different types of organizations since the customers’ demands and priorities for many products and services will change [

15,

42]. Therefore, businesses are required to mindfully cope with unforeseen circumstances to adapt to the new environment and ultimately advance their sustainable growth [

43].

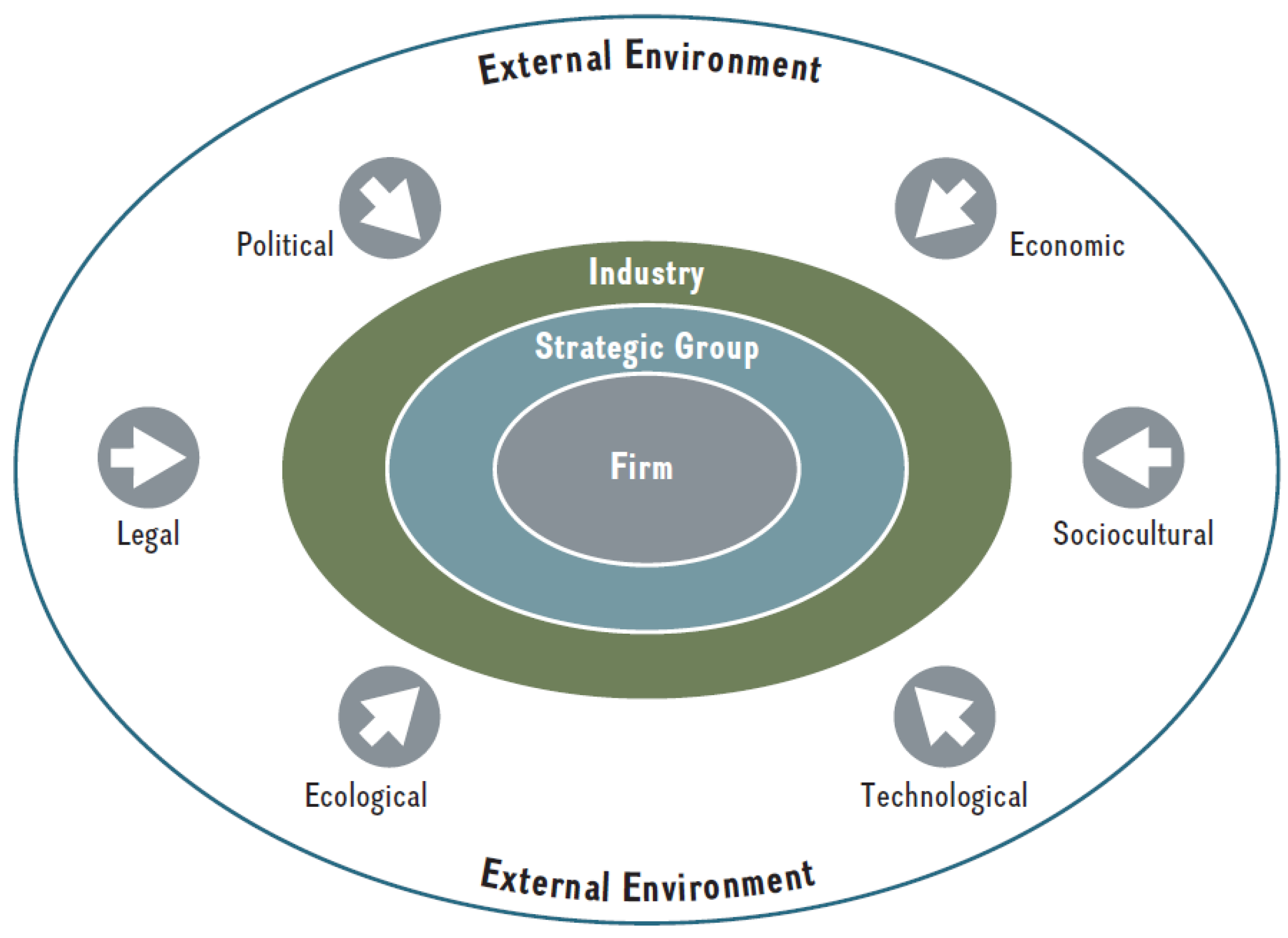

An organization’s external environment affects the firm’s potential to obtain and maintain a competitive advantage. Therefore, by analyzing external factors (the PESTEL model,

Figure 1), strategic leaders can add to organizational resilience by mitigating threats and leveraging opportunities. The PESTEL analysis presents a comparatively straightforward method to investigate, monitor, and assess the critical external factors such as the political, economic, sociocultural, technological, ecological, and legal factors that might impinge upon a corporation [

44].

Meyer (1982) recommended that any adaptations to jolts have three main phases of anticipatory, responsive, and readjustment. Most of the following literature on resilience has fundamentally embraced at least one of these three critical areas [

45]. The concept of adaptation plays a significant role in organizational resilience. Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003) believe that resilience is the ongoing ability to appropriately and successfully handle internal and external resources to respond to a crisis (p. 17). This ability to adapt to external changes adds to the existing organizational strength and future strength; in other words, it adds to organizational resilience.

Resilence has differing manifestations dependent on complementary aspects pertinent to overall business constructs, such as organizational culture, strategy, structure, etc. The interplay of the concept of resilience and processes links within the business model elements explain relationships between constructs. Therefore, aspects of the resilient configuration model from organizational culture need to refer to the assimilation of resilience as either a domain or a process. Mary Jo Hatch and Cunliffe (2006) have distinguished four elements or domains such as (a) organizational culture and identity; (b) organizational strategy; (c) corporate design, structure, and processes; and (d) organizational behavior and performance, which altogether are referred to “strategic response to the external environment.” However, organizations’ appropriate response implies a particular form of action, namely, reaction to a specific undesirable event in a resilient manner. Thus, “resilient strategic response to external environment” denominates a process that links the organization to its external environment factors (the PESTEL model) in the desired form.

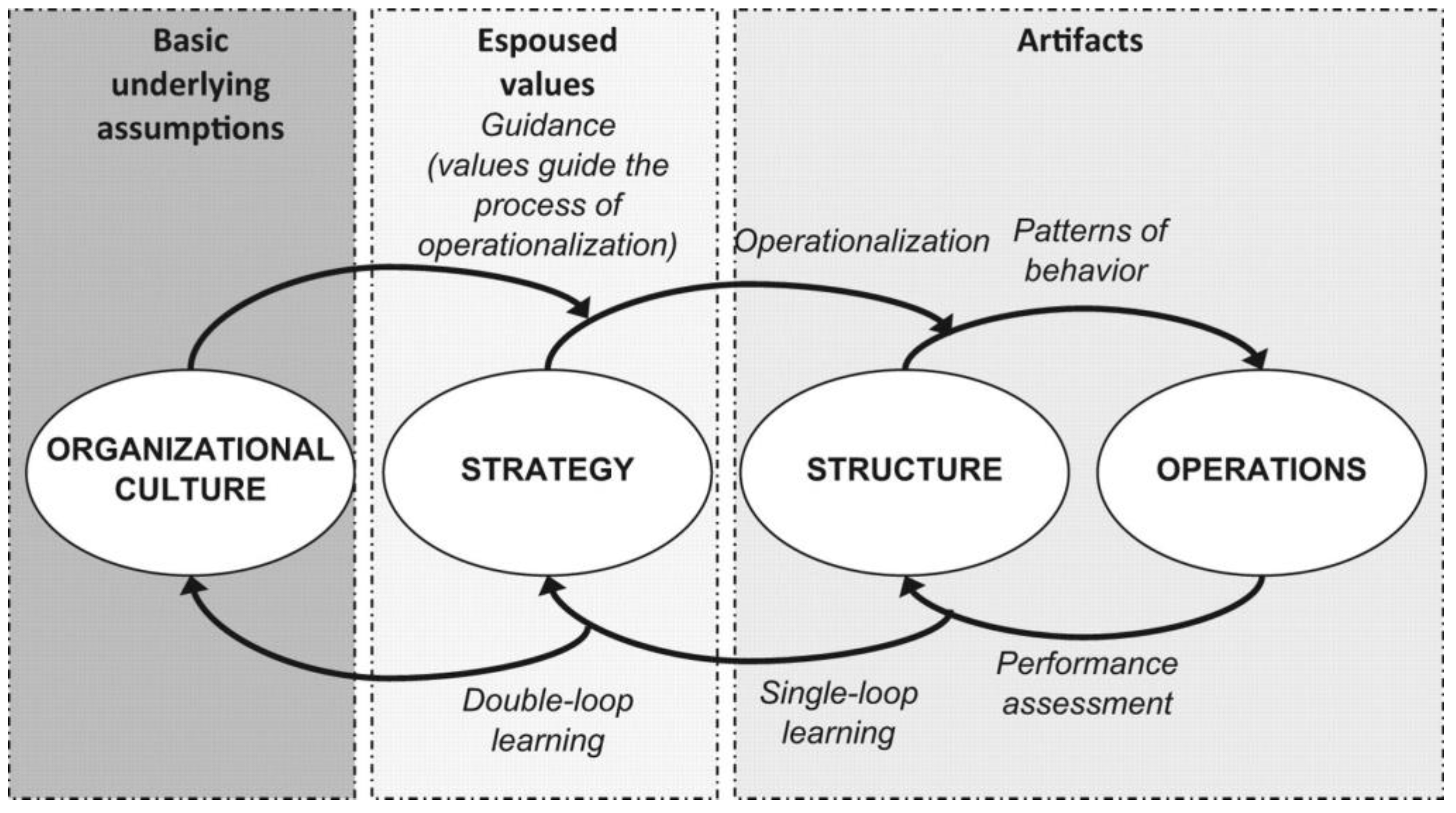

Hatch and Cunliffe’s (2006) model recommends multiple but obscure interplays between distinct domains to understand the nature of particular relationships between three parts more clearly. Following Hatch and Cunliffe’s model, Schein [

32] presented a modified solution by providing specific suggestions. Sage company amalgamated Hatch and Cunliffe’s (2006) domains approach with Schein’s organizational culture model [

32] and developed a more comprehensive model (

Figure 2).

When an organization is resilient, all internal elements and factors should be resilient. In order to turn the Comprehensive Organizational Model into a resilient organization model, resilience should be injected into all domains, including operations, structure, strategy, and organizational culture. Employee strengths have been identified as one of the primary sources of resilience in academic business resilience research [

46]. Luthans et al. (2007) have used employee-focused resilience as one of four fundamental individual factors (self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and employee-focused resilience) associated with positive organizational results. Employee-focused resilience research concentrates on prevailing individual characteristics that are related to resilience. Different individual capabilities are related to developing resilience, such as cognitive and behavioral capabilities [

47]. Williams et al. (2017) has identified four types of employee capabilities that are inherently connected with the ability to adjust to adversity, which ultimately directly impacts individual and organizational resilience.

Cognitive capabilities enable individuals to recognize potential agitations and respond appropriately [

48]. Behavioral capabilities evaluate individuals’ capacity to tolerate uncertainty and collaborate with others, especially under turbulent circumstances. Legnick-Hall et al. (2011) propose the concept of resilience capacity, which consolidates cognitive, behavioral, and contextual elements to foreseen threats and prepare the best possible responses to the crisis. Therefore, resilient employees in an organization increase productivity and job satisfaction [

49], lower turnover, and have the capacity to recover from the crisis shock swiftly and appropriately [

50]. An increasing body of research shows that resilient employees are more actively engaged, productive, and optimistic [

51]. The concept of resilience employee plays a significant role in organizational resilience. However, resilient employees are the outcome of a resilience culture. Developing a culture that fosters resilience requires creating a corporate culture that promotes trust, responsibility, and adaptability [

52]. Resilient organizational cultures not only enable employees to cope with environmental jolt properly and bounce back from setbacks faster but give employees a thorough understanding of how to take care of their physical and emotional well being.

It is crucial to keep in mind that a golden key to a resilient organizational culture is empowerment, which can be manifested in different forms in different organizations [

53]. According to the Towers Watson study, employers are required to have sustainable engagement by developing policies and practices to manage their stress level and overcome emotional hurdles during the tough time [

54]. During unprecedented circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic, swift changes happen in different forms, including economic volatility and an influx of new technologies. All of these changes have common features, such as uncertainty and ambiguity. To deal with such a crisis, a new normal should be defined. Therefore, organizations are in desperate need of leaders and employees who are innovative, flexible, adaptable, and agile, or resilient. Corporations, especially small organizations, need to create resilient organizational cultures that require a fundamental paradigm shift in the thinking process.

The next critical domain that needs to be enhanced with resilience characteristics is the strategy domain. Leaders have to prepare their organizations for adversity, and as such, they need to practice the proactive management of risks when it comes to anticipation of disruptive events. Organizational resilience develops over time and usually takes time to build a capacity to respond to adversity and learn from it. However, a self-learn organization brings resilience to its strategy. Resilience should become an integral part of the strategy-making process that results in a resilience strategy for the organization. The unique nature of an organization’s historical experience, core competencies, and lessons learned from a combination of circumstances due to dynamic market conditions is integral to the strategic development process. It is natural for an organization that has undergone disruptive events and has identified vulnerabilities to pragmatically concentrate on increasing the robustness of its key foundational aspects to prevent such historical risks that would damage crucial elements of its infrastructure. To improve the likelihood of success, some companies use strategic tools that identify the relationships between risks with devastating outcomes in avoiding risk cascading into a crisis. Scenario planning based on possible future events and the range of potential consequences is at the core of such a strategy-making process [

14].

Given an appropriate resilient culture within an organization, the best way forward is to formulate a resilient strategy to face uncertainty at the highest decision-making echelon. There have been a few attempts to formulate appropriate resilient strategies, among which the suggested strategic foresight formulation by J. Peter Scoblic (2020) seems to meet our requirements. In this formulation, the author suggests that independent of the ownership of the strategic process, decision makers should follow a well-defined set of key guidelines:

Invite the right people to participate.

Identify assumptions, drivers, and uncertainties.

Imagine plausible but dramatically different futures.

Inhabit those futures through dcenario planning.

Isolate strategies that will be useful across multiple possible futures.

Implement those strategies.

Ingrain the process.

The third domain of the Comprehensive Organizational Model is structure and operations that should be addressed from a resilient point of view. According to McKinsey, we are entering a new parametric analysis form called “uncertainty cube”. During this unprecedented time of the pandemic, the businesses are suffering from the greatest uncertainty of their time, and a such, they have no choice but to confine themselves to minimum macrolevel scenarios and financing parameters with overall direction but not much detailed guidance for managing their business [

55]. All businesses, especially small businesses that are more vulnerable to this uncertainty, need to develop a new adaptive structure to cope with this challenging circumstance.

It seems that adverse circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic might impact an organization’s business model [

16]. During such a crisis, an organization’s normal operation and structure may alter due to the change in market expectations and demands. Resilient organizations engage talented managers in taking responsibility for business continuity and managing the business operation in a resilient way [

33]. Studies show that sustainable leadership methods [

56] and social and environmental exercises [

57] such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) have significant impacts on business resilience. Andersson et al. (2019) have looked at organizational resilience as a holistic and perplexing concept. They believe that balancing organizational structures [

58] develops organizational resilience features such as risk awareness, adaptability, flexibility, improvisation, and increased collaboration. Balanced power distribution in organizational structure in conjunction with operational normative control can build capacity against unforeseen events [

27]. Therefore, it seems that organizational resilience attributes should be modulated into the organizational processes, and risk awareness is considered the basic characteristic of organizational resilience.

Resilient strategies can change over time. However, it is pivotal for organizations, especially small organizations, to be aware of previous performance deficits through performance/process assessment. One of the main traits of resilient organizations is the ongoing learning capability that evolves through time through the process of evaluation, correcting the error, and practicing adaptability [

11]. However, learning is inherently different from adaptation [

59]. For businesses might or might not learn from their previous mistakes. Organizational learning should promote individual and organizational behavior by effectively understanding the organizational environments, modifying the processes, and improving decision making [

60]. Amongst the organizational learning theories, single-loop and double-loop learning [

56] are the most cited fundamental theories [

61] because these theories mainly concentrate on the theory of action and individual behavior. Single-loop learning refers to an instrumental learning method that identifies errors and adjusting current strategies to new situations with no change in the values of a theory of action, while in contrast, double-loop learning, by contrast, refers to two feedback loops with a more profound means of learning, where there is a need for adaptations of values as well [

56].

Dring the COVID-19 pandemic, small businesses are struggling with an existential threat. In addition to the critical concern of the detrimental effect of COVID-19 on human lives, there is an apparent fear about the drastic economic downturn leading to a prolonged economic battle for many businesses. Small businesses that adopt resilient strategies, adaptability, and agility are most likely to weather the storm and have a future [

62]. It is fundamentally critical for small businesses to embrace pro-competitive approaches to build adaptive capacity. The resilient culture gives employees a thorough perspective on how to adjust and even take advantage of the new changes. Resilient and agile culture enables small businesses to maintain their core competency if it does not elevate it [

63]. The resilient approach empowers small businesses to strengthen their alignment with new environmental jolts and business facts by expanding the organizational capacity. Due to small businesses’ inherent nature, if these companies become resilient, they will emerge from the crisis even better than before [

64]. Resilient small organizations have the capability to evolve through time and technology [

65] and advance to the next paradigm towards online channels and learning to telework during the COVID-19 crisis [

45].

As is discussed earlier, agility and flexibility are two main traits of a resilient organization. However, small businesses can get benefit from their size of operations and become agile and flexible swiftly. Agile businesses change their structure in response to environmental jolts, including changes in business models or products according to novel market trends. As a matter of fact, what small organizations may lack in market position and productivity, they gain in agility and flexibility. The challenges posed by unprecedented situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic are embedded with uncertainty and insecurity, requiring resilient organizations’ calls [

63]. As Folke believes, resilience is not just about being tenacious or robust to environmental shock, but it is also about the opportunities that come with new changes [

51]. Therefore, challenging time holds opportunities for renewal, reinventing through innovation [

28], and creating new trends in the new market. However, small organizations need to have dynamic capabilities to embrace these opportunities, hinder threats, sustain competitiveness [

64], and prosper.

Small businesses that are resilient exhibit significant characteristics, such as the ability to respond adaptively and effectively to environmental jolt to avoid mishaps [

65]; the ability to recover swiftly and efficiently, and the ability to learn and adjust accordingly to ensure the survival of the business by keeping normative control over the organizational structure and vulnerability [

66,

67]. Small companies usually have limited internal resources, such as a pool of skills and financial abundance. However, they are less restrained by rigid hierarchical organizational structures. Consequently, open innovation partnerships and external knowledge integration are effective strategies that can be easily implemented for small businesses [

61]. As Välikangas & Georges L. Romme have rightfully stated, “The world is becoming turbulent faster than organizations are becoming resilient” [

68]. In this turbulent world filled with uncertainty, the world’s turbulence brings insecurity and the possibility of disruptions. Small businesses can sustain their competitiveness by enabling innovation and embracing the resilient culture and structure to anticipate, monitor, and respond to a crisis [

69] such as a coronavirus pandemic appropriately.

4. Results

It is paramount to consider the overarching effect of resilience on the environmental interaction of a small business. Congruent assimilation of resilience to a small business ecosystem requires a configuration model capable of distinguishing between domains and processes. This paper attempts to provide a unified approach through a conceptual framework that encompasses the inherent interrelationship of different organizational strategic development processes. The established literature on different layers of resilience seems to deal with each layer of organizational development separately. Literature review reveals that the highest level of a resilient organization, namely, a resilient culture, has received the most significant attention within the echelon of organizational development hierarchy. The next significant aspect of resilience appears to be operational resilience, which investigates an organization’s ability to bear threats and fulfill disaster recovery, including responsiveness to avoidance. This resiliency aspect focuses on the preventive ability that stems from system engineering practices [

65]. These practices have attempted to create robust operations under undesirable disturbances (which is referred to as regulation-constant behavior under agitation in the working environment). Application of robust system engineering has appeared in business management literature in terms of “mindfulness” that enables the cross-disciplinary transfer of concepts in enhanced organizational qualities essential for resilient performance [

70]. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) write about highly reliable organizations’ lessons: good management practices that generally apply but especially in the face of unexpected events or emergencies [

47].

Strategic resilience has received less attention than the previous two aspects and has been mentioned in conjunction with operational resilience. This literature is related to the studies of accidents that view them as eventual (difficult to avoid) endpoints of chains of escalating events [

55,

57,

65]. The following table (

Table 1) is an indication of the interrelationship of operational resilience to corresponding resilient strategies:

A broader approach to resilience is the only way to resist long-lasting organizational deterioration that requires strategic resilience. In the spirit of Karl Weick’s “safety is a non-dynamic event”, strategic resilience translates into dynamic prevention of damage to the organization from a jolt, thus strategically guaranteeing that a crisis never turns into devastation [

71,

72]. As earlier noted, strategic resilience is the most complex aspect of a resilient organization that builds the potential to respond to threats and even exploit it as a possible opportunity. According to Liisava Linkangas (2010), only the responses to sudden jolts (disturbances) belong to the operational resilience perspective. Any long-lasting imminent decay or decline due to market disruptions remains the focus of strategic resilience [

73].

The issue of organizational resilience is more cumbersome to small businesses in general [

74]. The difficulty stems from the lack of formal organizational development and limited resources to appropriately govern the company. Numerous causes are behind why such corporations struggle to adapt to new market realities in light of a catastrophic market event. Inadequate planning and organizational development efforts are among the chief reasons behind the lack of appropriate small companies’ resilience. For small companies that are either ill-prepared or not ready to handle unforeseen jolts, management tends to malfunction or lack the determination to lead efficiently [

75]. The chief reason behind management’s inadequacies in dealing with market jolts is the lack of significant resources and money for strategic planning. In addition to the lack of appropriate decision making in most small businesses, structural inertia in rigid organizational structures [

76] and strict operating processes may restrict any required adaptation from taking hold.

The culmination of the factors mentioned above will force a small company into a performance trap myopically. Such common failure traps transpire when the small company lacks the resilience to wait and observe if an appropriate strategy works in facing an adverse situation and keeps adjusting the strategy prematurely [

76]. Given the availability of viable and appropriate resilient strategy, the missing link in a resilient organization is a proper organizational structure suitable for implementing resilient strategies. Many small businesses suffer from an outdated organizational structure lacking appropriate flexibility and agility to adapt to the business’s operational requirements under stringent and adverse market conditions. Implementation of resilient strategies requires modern organization structures that:

Utilize IT-based decision making/knowledge sharing,

Have balanced power distribution,

Are fluid and dynamic,

Are highly adaptable to the changing needs,

Have integrated succession planning,

Have strategic fit, and

Are streamlined.

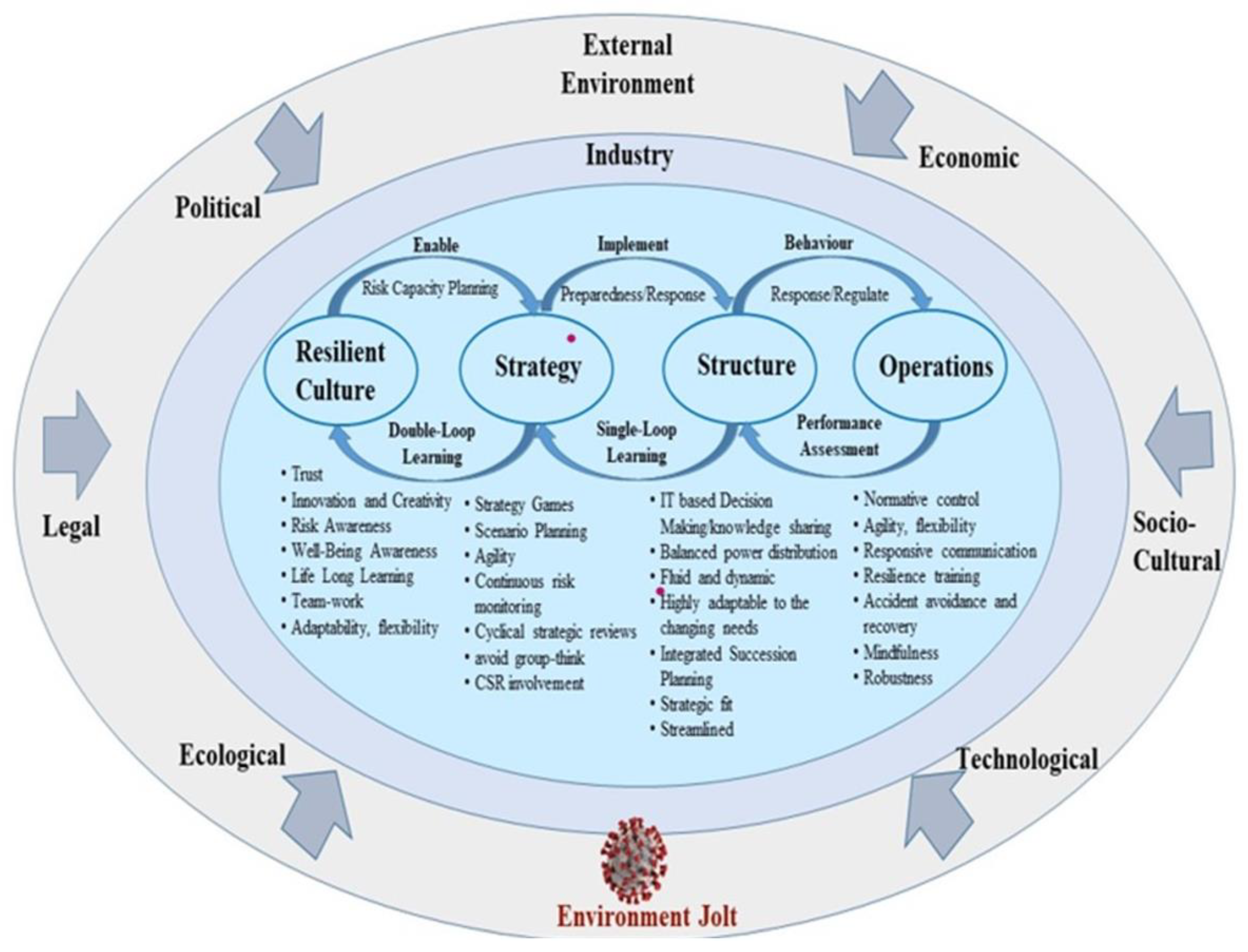

A resilient organization is the culmination of the integration of resilience to the four organizational aspects, namely culture, strategy, structure, and operation. These aspects are dynamically interdependent in a cause-and-effect fashion, as shown in the proposed framework (

Figure 3), depicting a small business’s inner-working. A resilient organization operates in a competitive environment. Each element of its resilience framework depends on the external factors shaping the business’s external environment. An organization’s external environment affects its potential to obtain and maintain a competitive advantage in all circumstances. Therefore, by integrating external factors according to the PESTEL model (

Figure 1), strategic decision makers can achieve organizational resilience by relieving threats and turning them into opportunities if plausible.

The proposed resilient organization framework is a holistic and procedural methodology that enables small businesses to prepare and execute appropriate resilience to their organization. As depicted, the understanding of relationships and inner-workings of all aspects of a resilient organization is the surest way to achieving a robust business operation. The proposed conceptual framework ensures a comprehensive and systematic approach that empowers the small business planners to rise to market jolts and challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.