Establishing Rational Processing Parameters for Dry Finish-Milling of SLM Ti6Al4V over Metal Removal Rate and Tool Wear

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

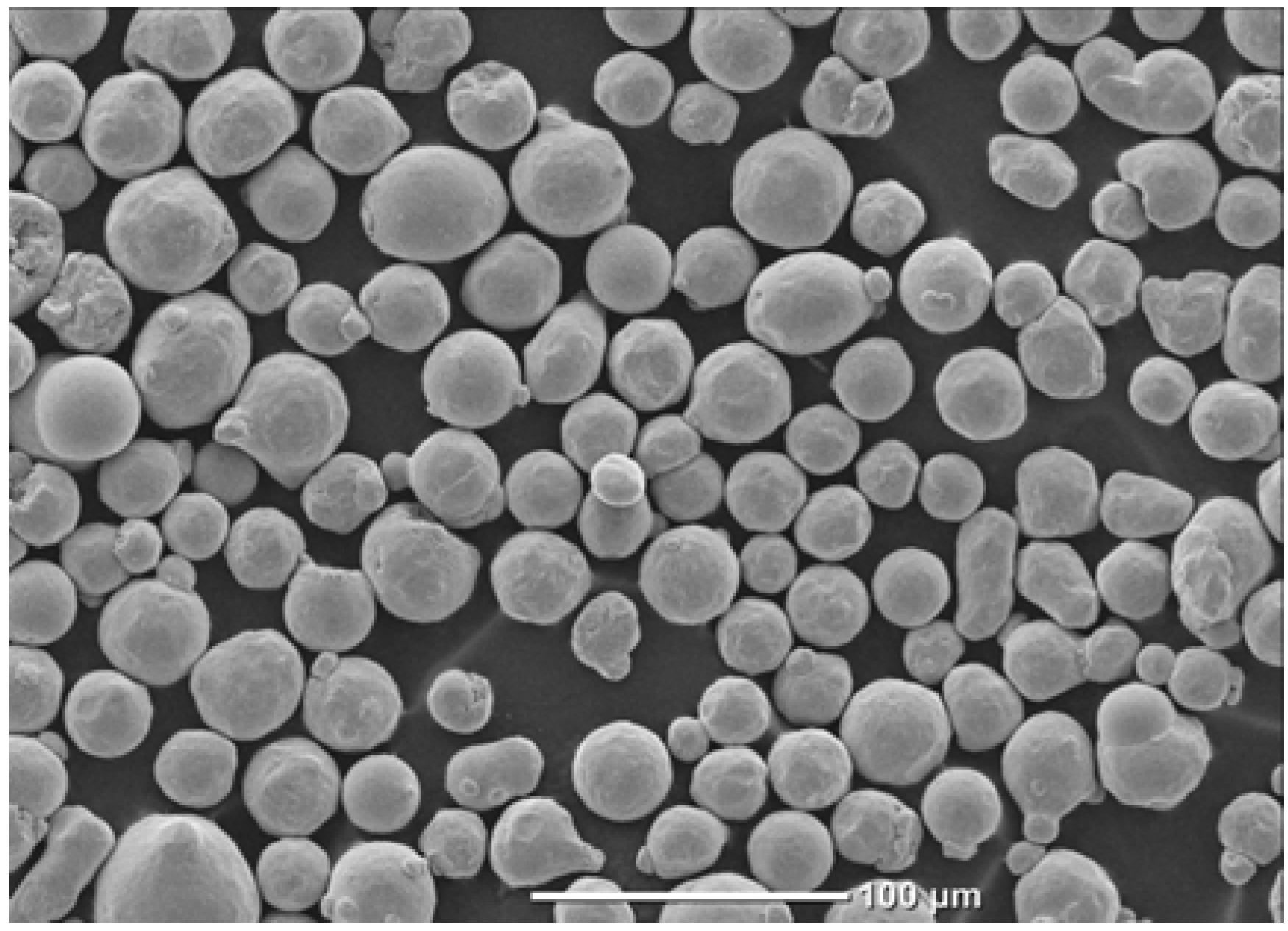

2.1. SLM Parameters

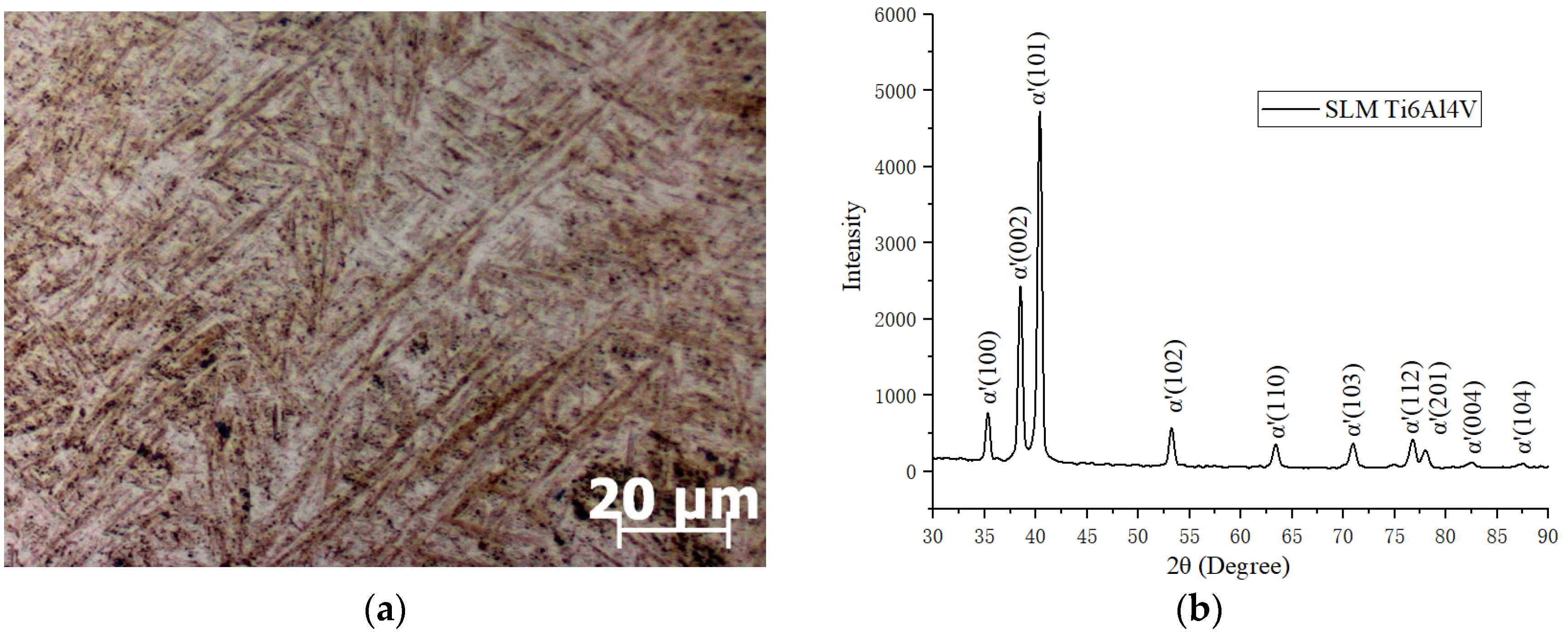

2.2. Microstructure and Phase Composition

2.3. Microhardness and Tensile Tests

2.4. Milling

2.5. Methodology for Estimating Wear Mechanisms for Milling Cutters

2.6. Evaluation of the Quality of the Machined Surface

3. Results

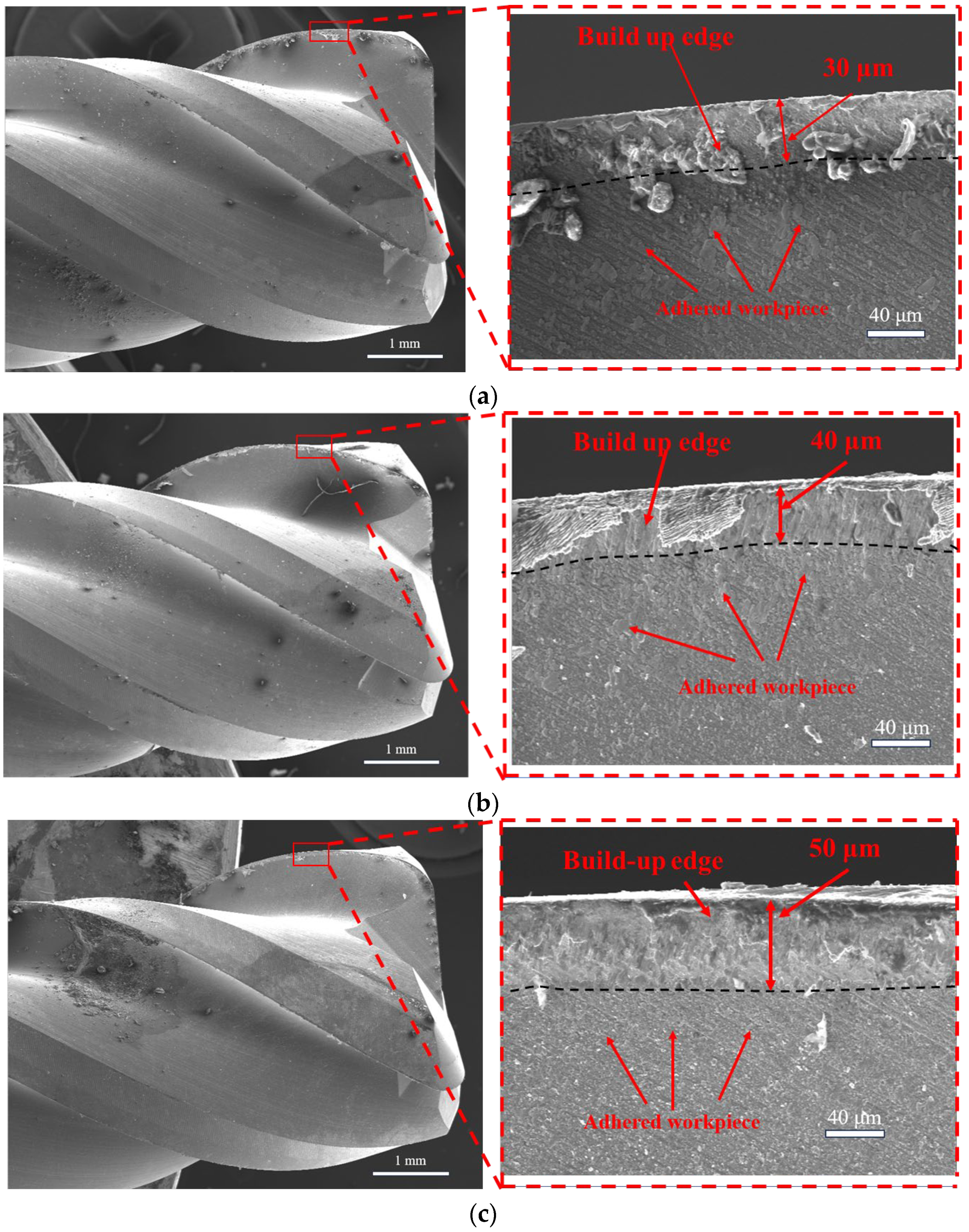

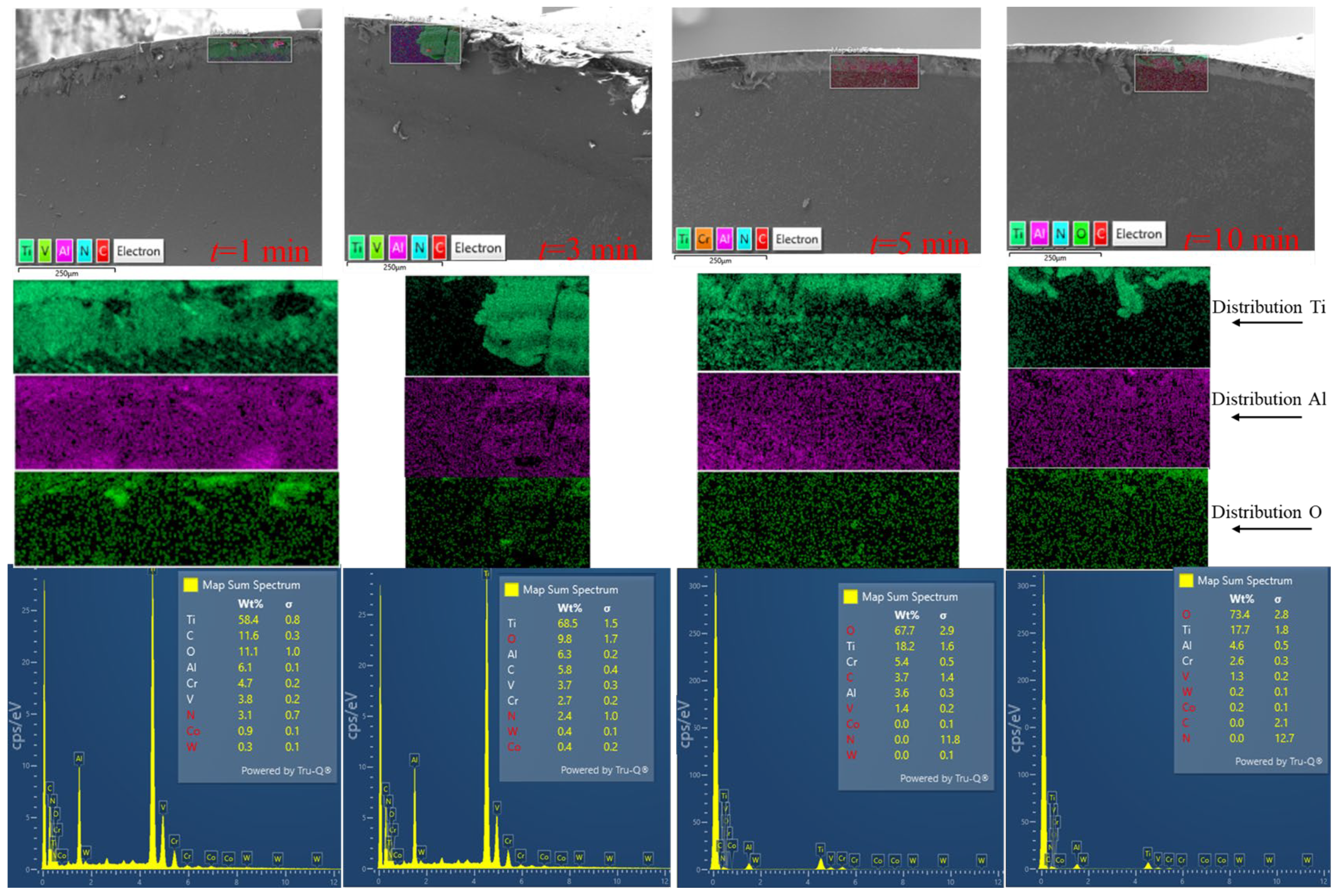

3.1. Analysis of the Cutting Edges (Leading Surfaces) of the End Mills

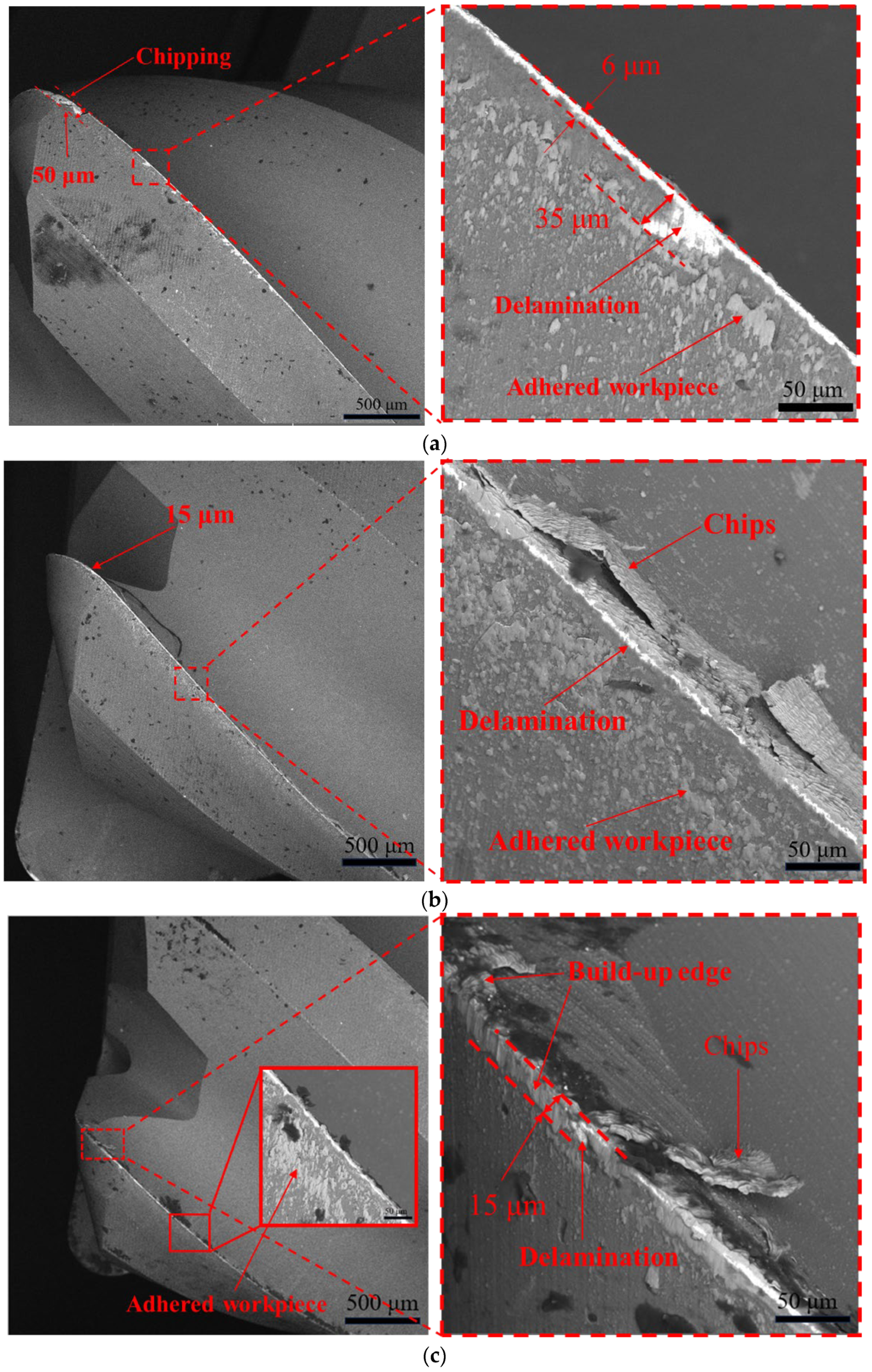

3.2. Wear of the Flank Surface of the End Mills

3.3. Wear of the End Mills with Time

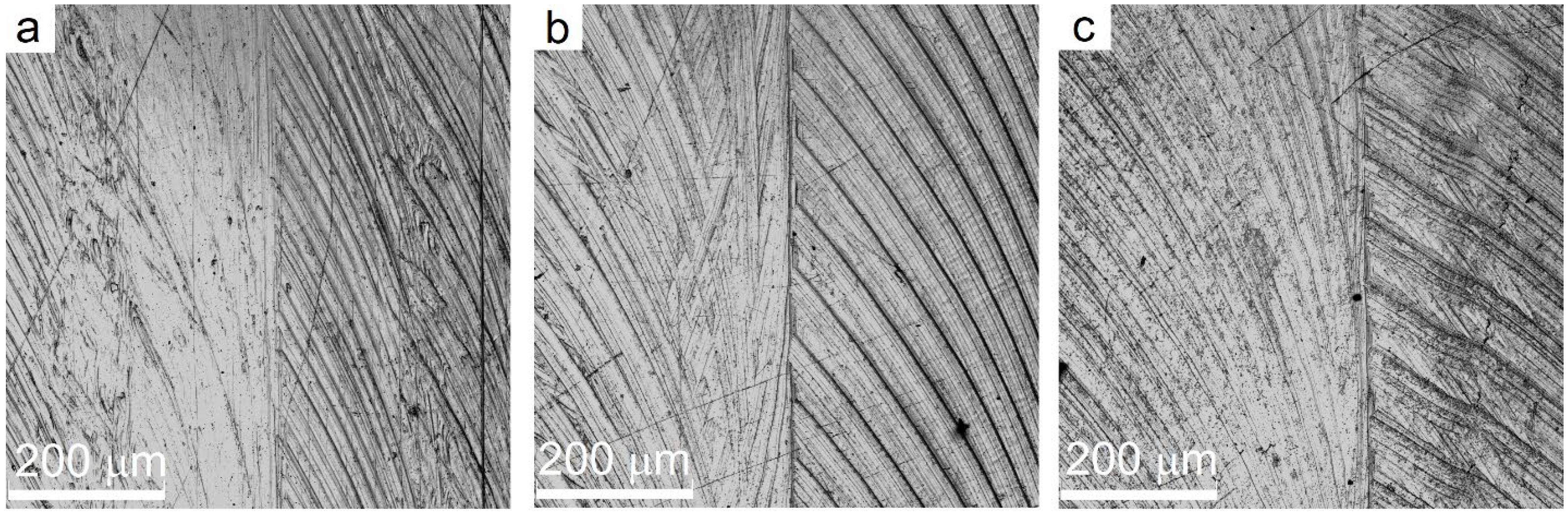

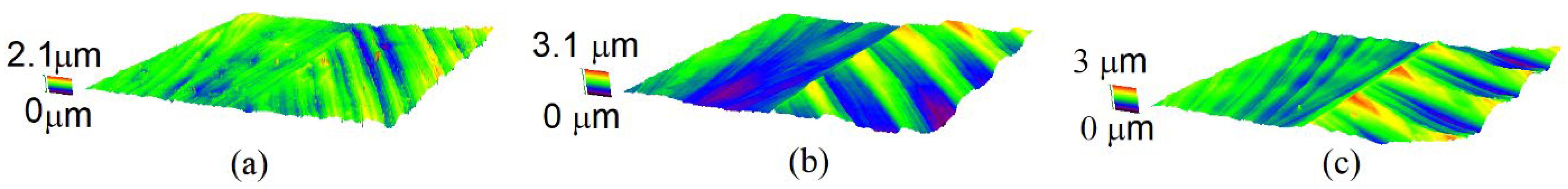

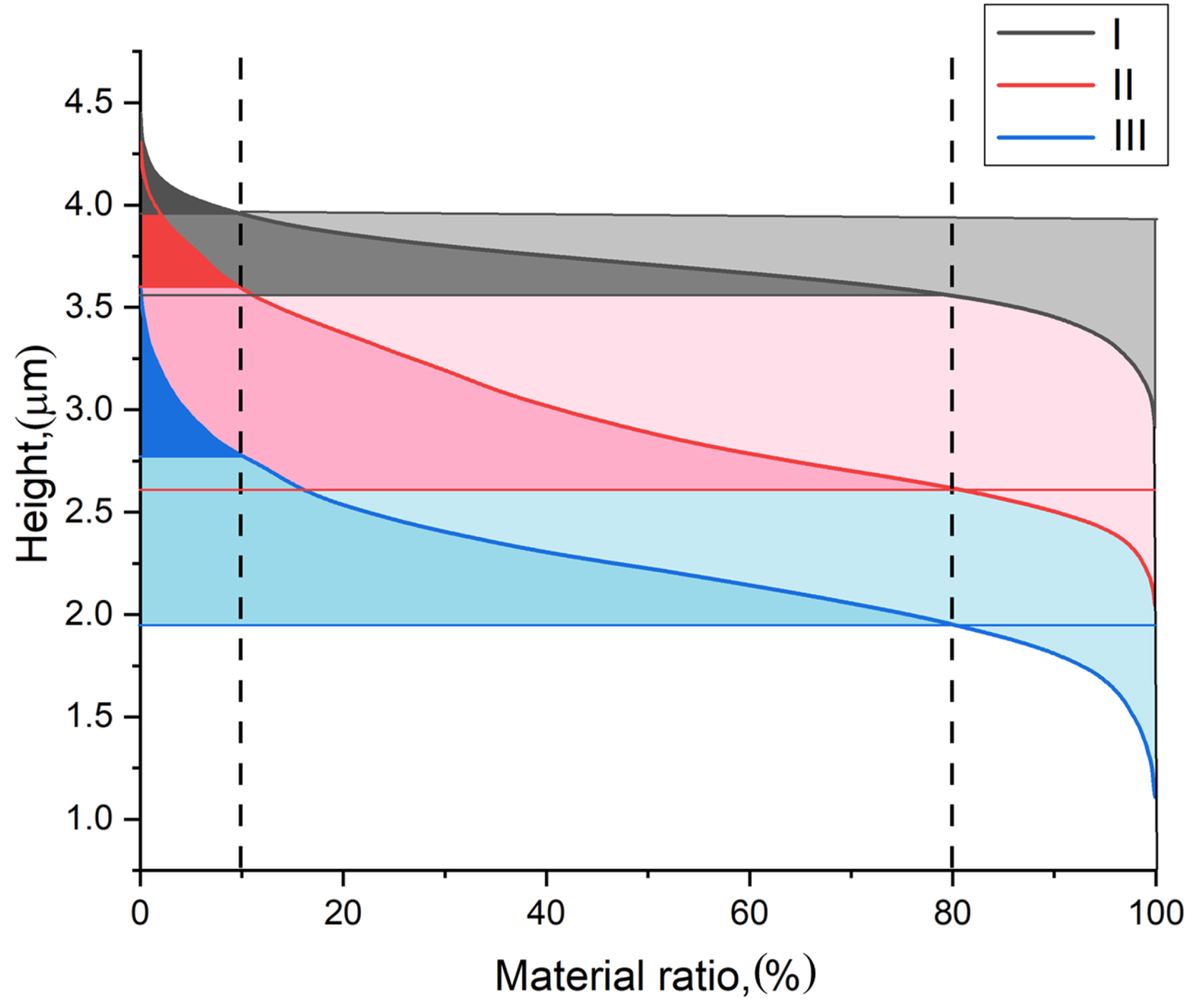

3.4. The Quality of the Machined Surface

4. Discussion

- -

- Firstly, the milling parameters in mode III were selected in such a way as to avoid premature formation of chipping on the cutting edge. Chipping was formed on the flank surface only in long-term milling (above 20 min), when using mode I (as opposed to modes II and III);

- -

- Secondly, using mode III at the low RDOC value of 60 m/min and the high feed level of 400 mm/min allowed an increase in the volume of the removed material per tooth, improving the milling speed. These parameters also enabled a decrease in the contact time (friction) between the flank surface and the SLM Ti6Al4V sample, reducing its wear. However, it should not be overlooked that excessive feed per tooth may lead to both failures of teeth and accelerated wear of end mills;

- -

- -

- Fourthly, the AlCrN coating possessed high wear resistance (as described above). In this study, oxygen contained in the air interacted with both aluminum and chromium in the protective coating first, but with titanium only (Figure 11). Since both Cr2O3 and Al2O3 particles were characterized by greater wear resistance, they had to suppress the development of diffusion wear.

5. Conclusions

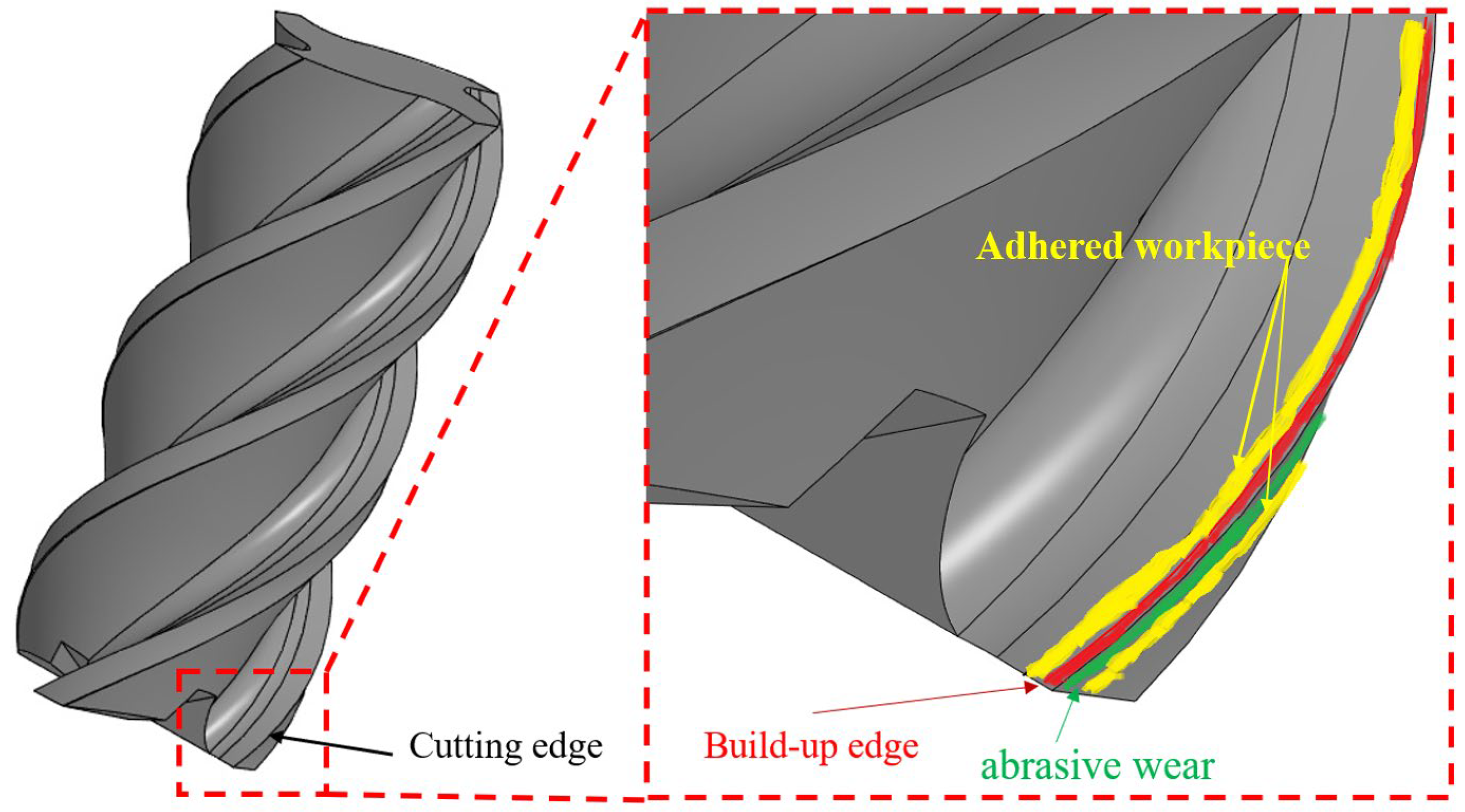

- When using all the applied milling modes, the identical tool wear mechanism was observed. Built-up edges mainly developed on the leading surfaces, increasing the surface roughness on the SLM Ti6Al4V samples but protecting the cutting edges. However, abrasive wear was mainly characteristic of the flank surfaces that accelerated peeling of the protective coatings and increased wear of the end mills. Therefore, if the dry milling is to be used, it is recommended to apply a more wear-resistant coating to protect the tool’s flank surface. This will improve the machinability of additive titanium alloys under dry finish milling conditions.

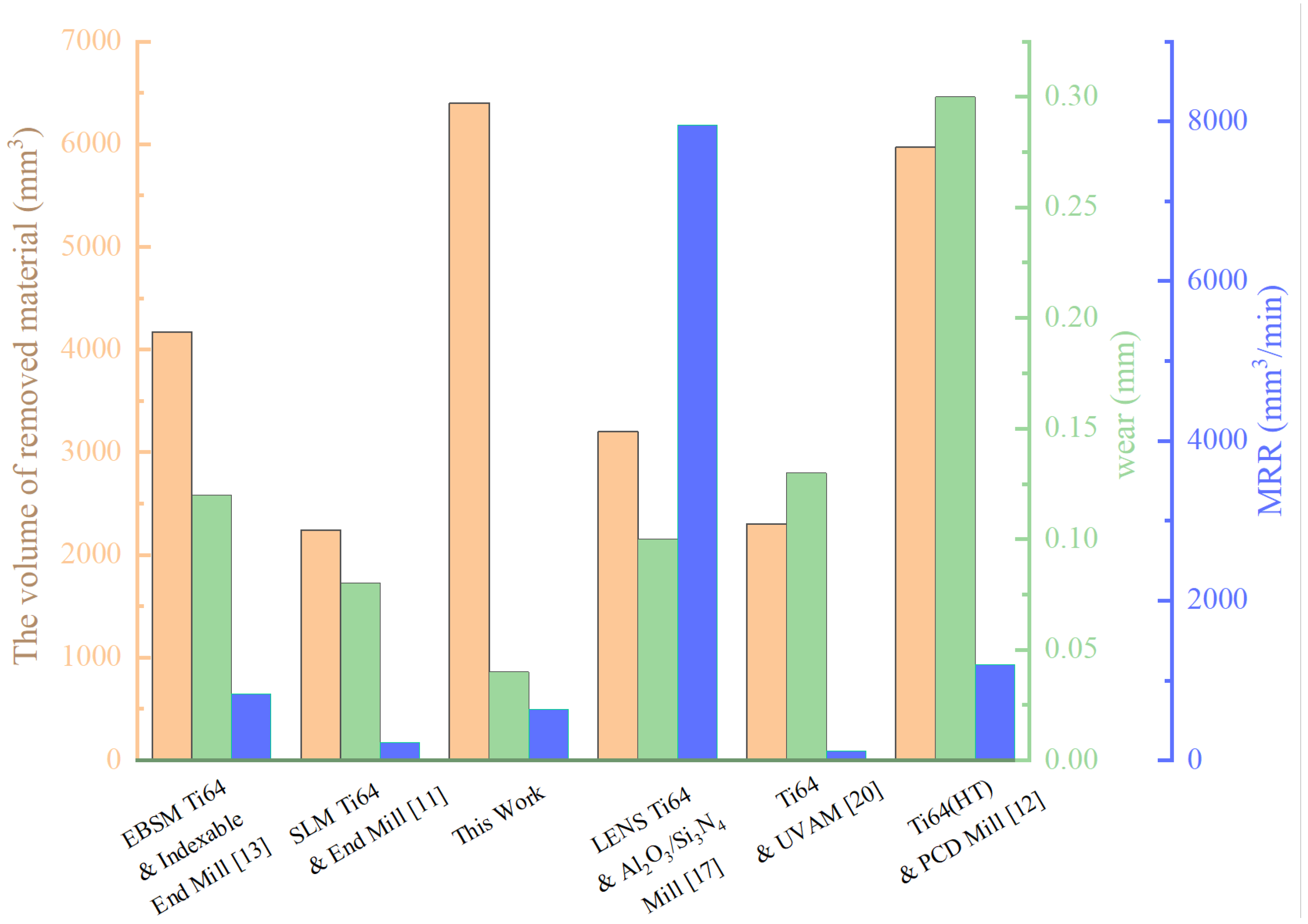

- Compared to the literature data, when mode III is selected, the end mill provided both the highest MRR value of 640 mm3/min and the highest volume of the removed material of 6400 mm3 at the negligible wear of 40 μm. The most likely reasons were (i) the selected parameters enabled to avoid premature chipping; (ii) the AlCrN coating had high wear resistance, including under the implemented conditions; (iii) since a built-up edge mainly occurs on the rake surface close to the cutting edge, its formation can hinder the direct contact between the tool and the workpiece to a certain extent, thereby slowing down the tool wear.

- Upon milling under the dry finish conditions, oxygen contained in the air interacted with both aluminum and chromium in the protective coatings first, but with titanium in the SLM Ti6Al4V samples only. This phenomenon prevented the development of diffusion and abrasive wear, and generally slowed down the process of wear of the protective coatings.

- Mode III provided the maximum MRR value and negligible wear of the end mill, but its main disadvantage was the high average surface roughness on the SLM Ti6Al4V sample. Mode II was characterized by both the lowest average surface roughness and the lowest wear of the end mill, but an insufficient MRR value as well. Since these two modes differed only in the feed rates, their values should be optimized in the range from 200 to 400 mm/min.

- The prospects of the study are related to estimating the long-term performance of cutting tools under established milling parameters in order to deeper reveal the regularities of their wear and failure. In addition, it is perspective to evaluate other milling factors that affect the surface roughness on the AM Ti6Al4V samples, including the search for conditions that reduce wear on the flank surfaces, while ensuring acceptable MRR levels. Of practical relevance is a comparative study of the performance of cutting tools of different manufacturers when the identical milling modes are employed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikon-slm-Solutions. Available online: https://nikon-slm-solutions.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Antolak-Dudka, A.; Czujko, T.; Durejko, T.; Stępniowski, W.J.; Ziętala, M.; Łukasiewicz, J. Comparison of the Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Resistance Properties of Ti6Al4V Samples Manufactured by LENS and Subjected to Various Heat Treatments. Materials 2024, 17, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shin, Y.C. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy: A review. Mater. Des. 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Cao, S.; Cao, Z.; Kovalchuk, D.; Wu, S.; Liang, E.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Wu, F.; et al. Fine equiaxed β grains and superior tensile property in Ti–6Al–4V alloy deposited by coaxial electron beam wire feeding additive manufacturing. Acta Metall. Sin. 2020, 33, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baufeld, B.; Brandl, E.; Van der Biest, O. Wire based additive layer manufacturing: Comparison of microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti–6Al–4V components fabricated by laser-beam deposition and shaped metal deposition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2011, 211, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keist, J.S.; Palmer, T.A. Development of strength-hardness relationships in additively manufactured titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 693, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesik, W. Hybrid additive and subtractive manufacturing processes and systems: A review. J. Mach. Eng. 2018, 18, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, W.; He, Y. Deformation prediction and experimental study of 316l stainless steel thin-walled parts processed by additive-subtractive hybrid manufacturing. Materials 2021, 14, 5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.-P.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Jin, X.; Xiao, M.-Z.; Su, J.-Z. Study of hybrid additive manufacturing based on pulse laser wire depositing and milling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, S.; Morandeau, A.; Chalon, F.; Leroy, R. Influence of finish machining on the surface integrity of Ti6Al4V produced by selective laser melting. Procedia Cirp 2016, 45, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaie, K.S.; Melotti, S.; Rabelo, A.; Paiva, J.M.; Elbestawi, M.A.; Veldhuis, S.C. Machinability of SLM-produced Ti6Al4V titanium alloy parts. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.A.; Feng, P.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, D.; Wu, Z. Influence of microstructure and hardness on machinability of heat-treated titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V in end milling with polycrystalline diamond tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 86, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, S.; Duchosal, A.; Chalon, F.; Leroy, R.; Morandeau, A. Thermal study during milling of Ti6Al4V produced by Electron Beam Melting (EBM) process. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 38, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Wei, R.; Li, C.; Ko, T.J. Study of chip adhesion behavior in titanium alloy dry milling process based on image extraction technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, A.; Bruschi, S.; Ghiotti, A.; Bariani, P. Analysis of tool wear in cryogenic machining of additive manufactured Ti6Al4V alloy. Wear 2015, 328, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhov, V.P. The assessment of cutting tool wear. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2004, 44, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ming, W.; An, Q.; Chen, M. New observations on wear characteristics of solid Al2O3/Si3N4 ceramic tool in high speed milling of additive manufactured Ti6Al4V. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 5876–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airao, J.; Kishore, H.; Nirala, C.K. Measurement and analysis of tool wear and surface characteristics in micro turning of SLM Ti6Al4V and wrought Ti6Al4V. Measurement 2023, 206, 112281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, H. Experimental study of tool wear and its effects on cutting process of ultrasonic-assisted milling of Ti6Al4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 2917–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Z. Comparative investigation of tool wear mechanism and corresponding machined surface characterization in feed-direction ultrasonic vibration assisted milling of Ti–6Al–4V from dynamic view. Wear 2019, 436, 203006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, D.J. The parameter rash—Is there a cure? Wear 1982, 83, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, D.J. Handbook of Surface and Nanometrology; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, R.K.; De Groot, P. The standards rash—Is there a cure? Int. J. Metrol. Qual. Eng. 2015, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X. A tool life prediction model based on Taylor’s equation for high-speed ultrasonic vibration cutting Ti and Ni alloys. Coatings 2022, 12, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Cai, X.; Yu, D.; An, Q.; Ming, W.; Chen, M. Effect of material microstructure on tool wear behavior during machining additively manufactured Ti6Al4V. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2019, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, W.; Zhang, C.; Jamil, M.; Khan, A.M. Tool wear, surface quality, and residual stresses analysis of micro-machined additive manufactured Ti–6Al–4V under dry and MQL conditions. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gant, A.J.; Gee, M.G.; Orkney, L.P. The wear and friction behaviour of engineering coatings in ambient air and dry nitrogen. Wear 2011, 271, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.M.; Mathew, N.T.; Baburaj, M. Sustainable milling of Ti-6Al-4 V super alloy using AlCrN and TiAlN coated tools. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.Y.; Jie, J.L.L.; Yan, L.Y.; Dayou, J.; Sipaut, C.; Bin Madlan, M.F. Frictional and wear behaviour of AlCrN, TiN, TiAlN single-layer coatings, and TiAlN/AlCrN, AlN/TiN nano-multilayer coatings in dry sliding. Procedia Eng. 2013, 68, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting Tools. Available online: https://globalmall.cxtc.com/#/product/productSecond?catalogueCode=21 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Arlyapov, A.; Volkov, S.; Promakhov, V.; Matveev, A.; Babaev, A.; Vorozhtsov, A.; Zhukov, A. Study of the machinability of an Inconel 625 composite with added NiTi-TiB2 fabricated by direct laser deposition. Metals 2022, 12, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, F.; Xue, X.; Zheng, Y.; Bai, Q. Study on the Surface Quality of Overhanging Holes Fabricated by Additive/Subtractive Hybrid Manufacturing for Ti6Al4V Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, N.V.; Kozlov, V.N.; Qi, M.; Tynchenko, V.S.; Kononenko, R.V.; Konyukhov, V.Y.; Valuev, D.V. Production of workpieces from martensitic stainless steel using electron-beam surfacing and investigation of cutting forces when milling workpieces. Materials 2023, 16, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lacalle, L.N.L.; Campa, F.J.; Lamikiz, A. Milling. In Modern Machining Technology; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2011; pp. 213–303. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, B.; Long, H.; Yu, N. Research on Efficient and Stable Milling Using CNC Small Size Tool. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Seminar on Modern Cutting and Measurement Engineering, Beijing, China, 10–12 December 2010; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; Volume 7997, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Chen, J.C.; Kirby, E.D. Surface roughness optimization in an end-milling operation using the Taguchi design method. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 184, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, V.; Gerasimov, A.; Kim, A. Distribution of Contact Loads Over the Flank-Land of the Cutter with a Rounded Cutting Edge. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanical Engineering, Automation and Control Systems 2015 (MEACS2015), Tomsk, Russia, 1–4 December 2015; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2016; Volume 124, p. 012173. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Richard Liu, C. Machining titanium and its alloys. Mach. Sci. Technol. 1999, 3, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilewicz, A.; Jedrzejewski, R.; Myslinski, P.; Warcholinski, B. Structure, morphology, and mechanical properties of AlCrN coatings deposited by cathodic arc evaporation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti | Al | V | Fe | C | N | O | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal. | 6.2 | 4.2 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.005 |

| Sample Orientation | X-Y | Y-Z | X-Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ra (µm) | 8.91 ± 0.53 | 4.54 ± 0.21 | 3.64 ± 0.16 |

| Type AM | Condition | Orientation | UTS, MPa | YS, MPa | El, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLM | As-built, not machined | - | 1180 ± 10 | 1035 ± 10 | 5 ± 1 | This work |

| EBSM | As-built, not machined | - | 913 | 830 | 13.1 | [15] |

| LENS | As-built, not machined | - | 995 ± 8 | 929 ± 32 | 6.8 ± 1.7 | [2] |

| WAAM | As-built, not machined | Vertical | 915–935 | - | 10.5 | [5] |

| Horizontal | 990–1032 | - | 4.5 | |||

| EBM | HT-ed, 650 °C for 1 h, 920 °C for 3 h, 540 °C for 4 h | Vertical | 972.5 ± 2.5 | 842.5 ± 2.5 | 19.0 ± 1.0 | [4] |

| Horizontal | 982.5 ± 7.5 | 858.0 ± 8.0 | 18.5 ± 0.5 | |||

| WLAM | As-built, not machined | Vertical | 930–950 | - | 15–18 | [5] |

| Horizontal | 945–980 | - | 6.3–10 | |||

| Wrought | - | - | 1063 | 966 | ~13.8 | [3] |

| Mode | ADOC (ap), mm | RDOC (ae), mm | Feed Speed (Vf), mm/min | Cutting Speed (Vc), m/min | Material Removal Rate (MRR), (mm3/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 4 | 0.2 | 200 | 60 | 160 |

| II | 4 | 0.4 | 200 | 60 | 320 |

| III | 4 | 0.4 | 400 | 60 | 640 |

| Mode | Max Cutting Thickness amax | Built-Up Edge | Max Wear (Flank Surface) | Adhered Workpiece | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rake Surface | Flank Surface | ||||

| Ⅰ | 0.002 mm | 30 ± 2 μm | - | 35 ± 2 μm | + |

| Ⅱ | 0.004 mm | 40 ± 3 μm | - | 15 ± 1 μm | ++ |

| Ⅲ | 0.008 mm | 50 ± 3 μm | 15 ± 1 μm | 15 ± 1 μm | +++ |

| Mode | Sa, μm | Sz, μm | Dale Void Volume (Vvv), μm3/μm2 | Core Void Volume (Vvc), μm3/μm2 |

Peak Material Volume

(Vmp), μm3/μm2 | Core Material Volume (Vmc), μm3/μm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⅰ | 0.156 ± 0.012 | 8.27 ± 0.11 | 0.029 ± 0.003 | 0.233 ± 0.011 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 0.166 ± 0.008 |

| Ⅱ | 0.351 ± 0.023 | 6.82 ± 0.08 | 0.028 ± 0.003 | 0.606 ± 0.031 | 0.023 ± 0.002 | 0.371 ± 0.015 |

| Ⅲ | 0.296 ± 0.016 | 4.23 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.506 ± 0.024 | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 0.318 ± 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panin, S.V.; Filippov, A.V.; Qi, M.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Z. Establishing Rational Processing Parameters for Dry Finish-Milling of SLM Ti6Al4V over Metal Removal Rate and Tool Wear. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5030053

Panin SV, Filippov AV, Qi M, Ding Z, Zhang Q, Han Z. Establishing Rational Processing Parameters for Dry Finish-Milling of SLM Ti6Al4V over Metal Removal Rate and Tool Wear. Construction Materials. 2025; 5(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5030053

Chicago/Turabian StylePanin, Sergey V., Andrey V. Filippov, Mengxu Qi, Zeru Ding, Qingrong Zhang, and Zeli Han. 2025. "Establishing Rational Processing Parameters for Dry Finish-Milling of SLM Ti6Al4V over Metal Removal Rate and Tool Wear" Construction Materials 5, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5030053

APA StylePanin, S. V., Filippov, A. V., Qi, M., Ding, Z., Zhang, Q., & Han, Z. (2025). Establishing Rational Processing Parameters for Dry Finish-Milling of SLM Ti6Al4V over Metal Removal Rate and Tool Wear. Construction Materials, 5(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5030053