Review of Numerical Simulation of Overburden Grouting in Foundation Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Engineering Requirements

1.2. Review of Research Status

1.3. Research Scope and Framework of This Paper

2. Core Theories and Foundations of Numerical Simulation for Overburden Grouting

2.1. Core Governing Equations of Numerical Simulation

2.2. Numerical Characterization and Parameter Optimization of Material Properties

2.3. Comparison and Selection of Numerical Simulation Methods

2.4. Application of High-Performance Computing in Overburden Grouting Numerical Simulation

3. Engineering Application and Verification of Numerical Simulation

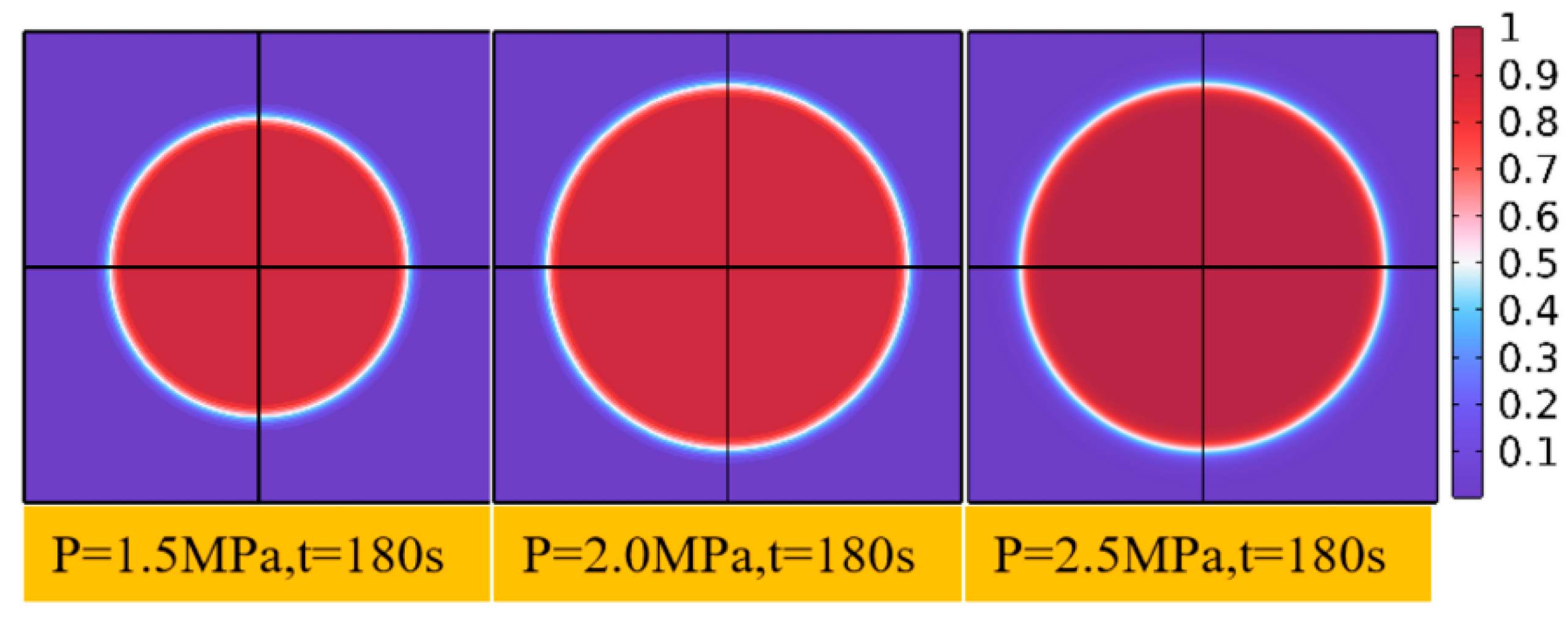

3.1. Advantages of Numerical Simulation in Grout Diffusion Law Research

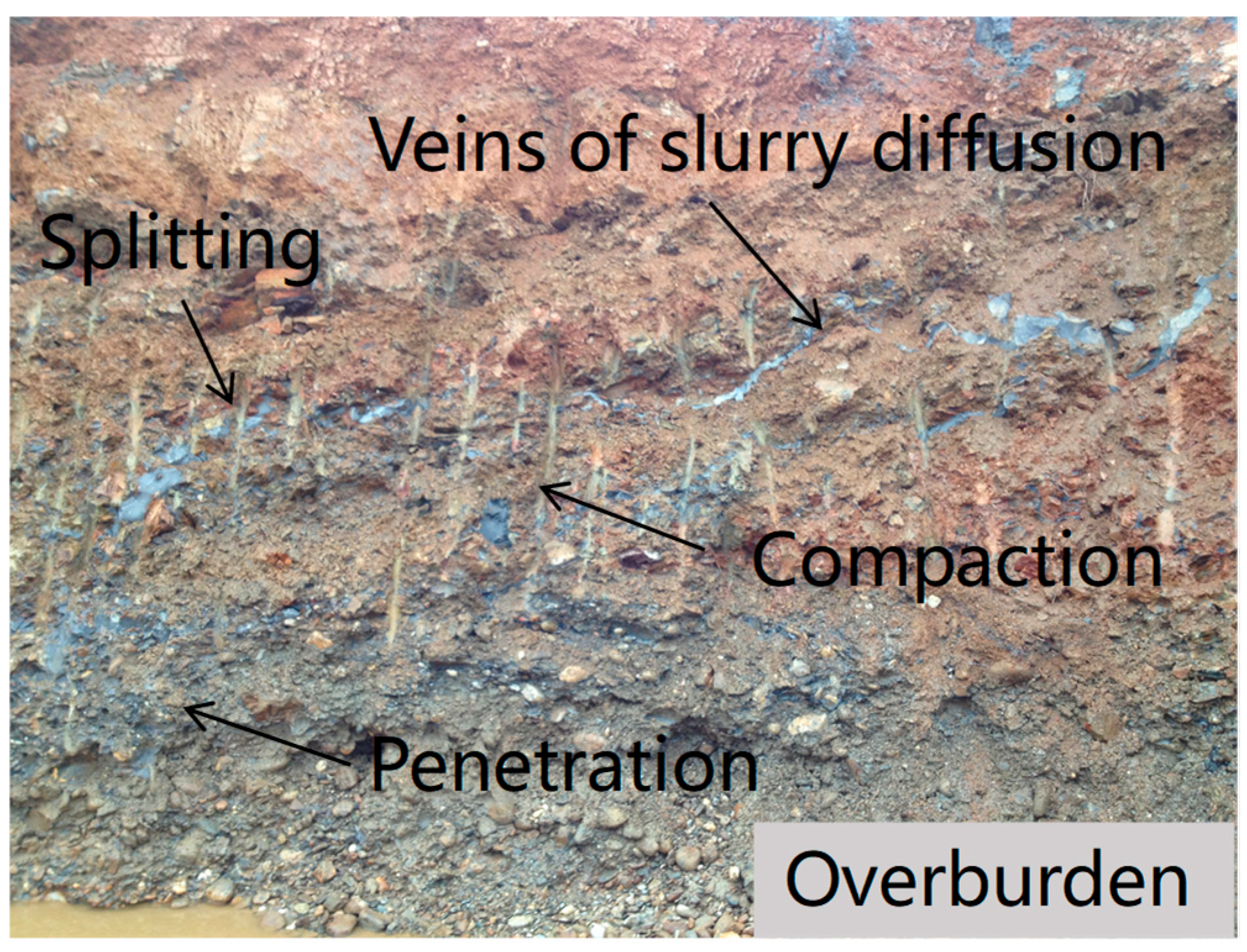

3.2. Simulation and Mechanism Revelation of Grout–Stratum Interaction

3.3. Numerical Support for Construction Parameter Optimization and Scheme Design

3.4. Numerical Verification Method System for Simulation Results

4. Discussion: Current Challenges and Development Trends

4.1. Current Challenges

4.2. Future Development Trends and Integration of Cutting-Edge Technologies

5. Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Core Conclusions

5.2. Research Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Diao, Y.; Lei, H. Experimental study on grouting in underconsolidated soil to control excessive settlement. Nat. Hazards 2016, 83, 1683–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z. Information and knowledge behind data from underground rock grouting. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, S. Treatment of the seepage problems at the kalecik dam (turkey). Eng. Geol. 2003, 68, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Yang, J.; Duan, M.Q.; Ma, X.F.; Li, G.C. The numerical simulation of rock mass grouting: A literature review. Eng. Comput. 2022, 39, 1902–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zhao, W.; Ma, Y.; Gen, H.L. Discrete element analysis of grouting reinforcement and slurry diffusion in overburden strata. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlett, R.D. Simulation of capillary-dominated displacements in microtomographic images of reservoir rocks. Transp. Porous Media 1995, 20, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.R.; Witherspoon, P.A. Steady state flow in rigid networks of fractures. Water Resour. Res. 1974, 10, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, J.; Saleh, K.; Langevin, M.A.; Mirza, S.; Bhutta, M.; Tahir, M. Properties of microfine cement grouts at 4 °C, 10 °C and 20 °C. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Håkansson, U.; Cvetkovic, V. Yield-power-law fluid propagation in water-saturated fracture networks with application to rock grouting. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 95, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordqvist, A.W.; Tsang, Y.W.; Tsang, C.F.; Dverstorp, B.; Andersson, J. A variable aperture fracture network model for flow and transport in fractured rocks. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiblier, J.A. A new three-dimensional modeling technique for studying porous media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1984, 98, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.J. Spreading model of grouting in rock mass fissures based on time-dependent behavior of viscosity of cement-based grouts. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 2709–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov, A. Non-Newtonian fluid flow in rough-walled fractures: A brief review. In Proceedings of the ISRM SINOROCK, 2013: ISRM-SINOROCK-2013-061, Shanghai, China, 18–20 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Dun, Z.; Ren, L.; Fang, J. Grouting effect on rock fracture using shear and seepage assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghalandis, Y.F. ADFNE: Open source software for discrete fracture network engineering, two and three dimensional applications. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 102, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, X.; Bai, W.; Yi, S.; Baghbani, A.; Lu, Y. Vibration mitigation performance of a novel grouting material in the tunnel environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 138995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Z.; Zhang, Q.S.; Liu, R.T.; Li, S.C.; Wang, H.B.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.J.; Zhu, G.X. Penetration grouting mechanism of quick setting slurry considering spatiotemporal variation of viscosity. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Potyondy, D.O.; Cundall, P.A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 1329–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, L.; Du, X.; Li, B.; Xue, B.H.; Wang, S.Y. Numerical and experimental research on diffusion characteristic of polymer slurry in narrow slot at constant pressure. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 22, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.; O’Sullivan, C. Effective simulation of flexible lateral boundaries in two- and three-dimensional DEM simulations. Particuology 2008, 6, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.T.; Ling, X.Z.; Ling, C.; Zhu, G.R. Numerical simulation for diffusion and pressure distribution of permeation grouting. Shuili Xuebao 2007, 3, 1402–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Joekar-Niasar, V. Pore-scale modelling techniques: Balancing efficiency, performance, and robustness. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 20, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano Leiva, D.; Kuncar Medina, C.; Montalva, G. Using a smartphone device to quantify particle size and shape descriptors. Acta Geotech. 2025, 20, 5277–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.Y.; Liu, Q.S.; Li, S.H.; Sang, H.W.; Kang, Y.S. Advance and review on grouting critical problems in fractured rock mass. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C.A.S.; Nick, H.M. A correlation for the matrix-driven increase in hydraulic permeability of rough-walled fractures. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Gong, W.; Chang, W.; Sun, M. Effects of pore characteristics on water-oil two-phase displacement in non-homogeneous pore structures: A pore-scale lattice boltzmann model considering various fluid density ratios. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 154, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawankar, S.; Kumar, S.; Pandit, B.; Tiwari, G.; Deshpande, V. Dynamic behaviour of un-grouted and grouted jointed samples of a brittle rock in split hopkinson pressure bar tests: Insights from experiments and DEM modelling. Eng. Geol. 2025, 351, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. An extended discontinuous deformation analysis for simulation of grouting reinforcement in a water-rich fractured rock tunnel. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrov, A. Flow of non-Newtonian fluids in single fractures and fracture networks: Current status, challenges, and knowledge gaps. Eng. Geol. 2023, 321, 107166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Z.; Huang, C.X.; Zhang, Q.S.; Pei, Y.; Li, Z.P.; Yang, W.D.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.C. Rock fissure grouting diffusion mechanism of quick-setting grout considering fluid-solid phase transition characteristics. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2024, 43, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Raffle, J.F.; Greenwood, D.A. The relation between the rheological characteristics of grouts and their capacity to permeate soil. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Paris, France, 17–22 June 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.L.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Li, W.J.; Cui, P.B.; Pan, Y.D. Study on the mechanism of column permeation grouting of Bingham fluid considering the spatial attenuation of viscosity. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2022, 41, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, L. Simulation of coupled hydro-mechanical interactions during grouting process in fractured media based on the combined finite-discrete element method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrov, A. Numerical modeling of steady-state flow of a non-newtonian power-law fluid in a rough-walled fracture. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 50, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Feng, H.; Chu, Y. Permeation grouting diffusion mechanism of quick setting grout. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Ma, L.; Reddy, S.C.; Attanayake, J.; Haese, R. Pore-to-darcy scale permeability upscaling for media with dynamic pore structure using graph theory. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.L.; Liu, X.; Bai, C.J.; Ge, Y.J. Comparison of meshing strategies at corners in engineering flow simulation. Eng. Mech. 2023, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Zhang, D.L. An FEM/VOF hybrid formulation for fracture grouting modelling. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 58, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.J.; Ding, P.F. Grouting diffusion mechanism of curtain grouting in pebble strata under flowing water conditions. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2025, 21, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, H.H.; Yi, Z.Y. A novel multiphysics modelling approach for grout loss analysis of backfill grouting in highly permeable soils during TBM tunnelling. Rock Soil Mech. 2023, 44, 2744–2756. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Zhao, Z.H.; Zhou, S.M. Block-based dem modeling on grout penetration in fractured rock masses. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2021, 17, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Grasselli, G.; Liu, Q.; Tang, X. Coupled hydro-mechanical analysis for grout penetration in fractured rocks using the finite-discrete element method. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 124, 104138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Nawnit, K. Grout diffusion in silty fine sand stratum with high groundwater level for tunnel construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 93, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.W.; Zhang, G.J.; Liu, J. Diffusion mechanism of split grouting. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 40, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.H.; Pan, D.D.; Li, S.C.; Bu, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.C. Latest research progress and future development direction of grouting numerical simulation in underground engineering. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 903–922. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Oh, J. Permeation grouting for remediation of dam cores. Eng. Geol. 2018, 233, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, G.L.; Chen, J.Q.; Chen, Y. A three-dimensional grouting model of slurry diffusion-particle deposition-permeability evolution in discrete fracture network. Comput. Geotech. 2026, 189, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Gustafson, G.; Fransson, Å. Stop mechanism for cementitious grouts at different water-to-cement ratios. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2009, 24, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, L.G.; Krizek, R.J. Hydrocarbon residuals and containment in microfine cement grouted sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2006, 18, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, N.; Zen, K. Finite element modeling of compaction grouting on its densification and confining aspects. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.; Yang, J. Effect of injection rate and water/cement ratio on fracturing grouting in soft rocks. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 165, 106913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjoo, H.; Monfared, A.E.F.; Jafari, S.; Saeid, M.A.; Schaffie, M. Simulation of newtonian and non-newtonian reactive fluids during the dissolution process in porous media using lattice boltzmann method. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2026, 170, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messa, G.V.; Malavasi, S. A CFD-based method for slurry erosion prediction. Wear 2018, 398, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazidenov, D.; Omirbekov, S.; Amanbek, Y. CFD-DEM modeling of fluid-driven fracture induced by temperature-dependent polymer injection. Particuology 2025, 105, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, G.P.; Wang, R.; Huang, S.; Li, G.W. Research on slurry diffusion characteristics of shield tunnel based on coupled DEM-FDM numerical simulatio. J. Eng. Geol. 2025, 33, 667–678. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Song, H.; Cheng, H.; Yang, C.; Ding, B.; Niu, Y. Solid waste-based bed-separation grouting materials: Experimental properties and CFD simulation of pipeline transport. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.M.; Dejam, M. Tracer dispersion due to non-newtonian fluid flows in hydraulic fractures with different geometries and porous walls. J. Hydrol. 2023, 622, 129644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Huo, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, H. Research on slurry seepage law and in-situ test based on the 3-D of goaf porosity in CFD modelling. Fuel 2024, 361, 130701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Liu, C.; Huang, H. Fluid-solid coupling numerical simulation of micro-disturbance grouting treatment for excessive deformation of shield tunnel. Undergr. Space 2024, 19, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stille, H.; Gustafson, G.; Hassler, L. Application of new theories and technology for grouting of dams and foundations on rock. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2012, 30, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, J.Y.; Stille, H. Applicability of using GIN method, by considering theoretical approach of grouting design. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2015, 33, 1431–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Ren, Z. Field grouting test study for high-level radioactive waste disposal at the beishan underground research laboratory. Int. J. Geomech. 2026, 26, 04025326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, G.; Stille, H. Stop criteria for cement grouting. Felsbau Z. Geomech. Ingenieurgeol. Bauwes. Bergbau 2005, 25, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, S.; Tafti, D.K. Two and three dimensional modeling of fluidized bed with multiple jets in a DEM–CFD framework. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 16, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virnovsky, G.A.; Friis, H.A.; Lohne, A. A Steady-State Upscaling Approach for Immiscible Two-Phase Flow. Transp. Porous Media 2004, 54, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Yu, H.; Jiang, B.; Liu, B. Method for measuring rock mass characteristics and evaluating the grouting-reinforced effect based on digital drilling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. Grouting geological model (GGM): Definition, characterization, modeling, and application in determining grouting material and pressure. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 6513–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzemder, A.S.H.; Singh, K. Influence of sedimentary structure and pore-size distribution on upscaling permeability and flow enhancement due to liquid boundary slip: A pore-scale computational study. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 190, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, D.; Zhong, L.; Li, Z.; Jin, L. Composite solid sand reinforcement grouting material preparation and diffusion characteristics of slurry-water replacement grouting. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, E04213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslannezhad, M.; Sayyafzadeh, M.; Tang, D.; You, Z.; Iglauer, S.; Keshavarz, A. Upscaling relative permeability and capillary pressure from digital core analysis in otway formation: Considering the order and size effects of facies. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 128, 205363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Li, P.; Wang, S. Experimental and numerical investigation on the diffusion characteristics of cement slurry grouted in medium sand soils. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 165, 106857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, N. Design and application of cement-based composite grouting material for high-temperature water plugging. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, E05532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharahi, G.; Faize, A.; Louzazni, M.; Mostapha, A.M.M.; Bayjja, M.; Driouach, A. Detection of cavities and fragile areas by numerical methods and GPR application. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 164, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Permeation diffusion mechanism of pulse grouting with bingham fluid considering tortuosity and spatiotemporal variations in viscosity. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 184, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Coe, J. Bayesian deep learning for uncertainty quantification and prediction of jet grout column diameter. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 179, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, R.; Ahmadi, M. Fast marching method assisted permeability upscaling using a hybrid deep learning method coupled with particle swarm optimization. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 230, 212211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiparan, N. Predicting compressive strength of grouted masonry using machine learning models with feature importance analysis. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Natarajan, Y.; Sri Preethaa, K.R.; Danushkumar, V.; Shamet, R.; Chen, J.; Xie, R.; Copeland, T.; Nam, B.H.; An, J. Advancements in sinkhole remediation: Field data-driven sinkhole grout volume prediction model via machine learning-based regression analysis. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2025, 6, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Salamanca-Medina, E.L.; Tomás, R. Assessment of compressive strength of jet grouting by machine learning. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, K.; Shen, S.L.; Zhou, A.; Yoo, C. Reinforcement learning-based optimizer to improve the steering of shield tunneling machine. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 4167–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, G. Numerical analysis of underground displacements stirred by compaction grouting during tunnel construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grouting Form | Application Scenarios | Objective | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consolidation grouting | Foundation reinforcement of hydraulic structures [1] | Improve mechanical properties, compactness, uniformity, elastic modulus, and bearing capacity of rock/soil; reduce deformation and uneven settlement; enhance overall integrity and anti-sliding stability of foundations [2] | Core Objective: strengthen the rock mass Scope: regional (surface reinforcement) Hole Arrangement: grid (e.g., plum blossom), sequentially encrypted Depth: shallow (several meters to tens of meters) Pressure: medium–low (mainly permeation) Key Feature: reinforces the “mass” |

| Reinforcement of tunnel and cavern surrounding rock | Improve bearing capacity, correct deviation, prevent collapse and seepage, block water flow, reinforce surrounding rock, suppress ground displacement, reduce surface settlement, lower permeability, facilitate excavation and support, reduce construction risks | ||

| Foundation reinforcement on fractured or weathered bedrock | Cement fractured rock blocks, enhance deformation resistance, improve integrity, eliminate weak interlayers, reduce differential settlement, block seepage paths, prevent seepage failure [3] | ||

| Curtain grouting | Basic anti-seepage measures in water conservancy projects | Cut off foundation seepage, maintain design head, meet economic benefits of reservoir/dam design; reduce uplift pressure, enhance anti-scouring and erosion capacity of embankments | Core Objective: anti-seepage and water blocking (form continuous low-permeability barrier) Scope: linear barrier (curtain formation) Hole Arrangement: linear (single/multiple rows), strictly ordered and encrypted Depth: moderate (several meters to tens of meters) Pressure: high (fracturing/permeation) Key Feature: establishes a “defense line” |

| Excavation and slope engineering | Reinforce underground structures, control groundwater impact on foundations and tunnels, increase soil shear resistance, reduce earth pressure | ||

| Mining and geological disaster management | Fill and cement to form impermeable walls, prevent groundwater inflow into mines, ensure mining safety [4] | ||

| Building foundation reinforcement | Treat fine cracks in walls and floors, improve overall strength and stability, prevent water inrush in retaining structures | ||

| Contact grouting | Dam engineering | Grout at concrete–rock interface, especially on steep slopes and contact surfaces, to enhance bonding | Core Objective: fill contact gaps Scope: point/seam (specific interfaces) Hole Arrangement: targeted pre-embedding Depth: very shallow (interface only) Pressure: low (avoid lifting/damage) Key Feature: bridges the “interface” |

| Underground engineering | Fill gaps between tunnel/mine lining and surrounding rock to prevent lining deformation or leakage | ||

| Metal structures | Grout between metal structures (e.g., pressure steel pipes, spiral cases) and concrete foundations to improve connection tightness and foundation integrity | ||

| Other | Microbial riverbank protection [5] | Cement sand particles to improve shear strength and overall slope integrity | Core Objective: ecological restoration Scope: point/seam (specific areas) Depth: shallow Pressure: low Key Features: low disturbance, environmentally sustainable |

| Marine pipeline laying | Enhance anti-sliding stability, improve shear resistance of marine rock/soil, and increase rock mass integrity | ||

| Microbial grouting for desert reinforcement | Improve soil structure, enhance engineering stability, support vegetation growth | ||

| Restoration of rock and soil cultural relics [6] | Form calcium carbonate waterproof layer to alleviate weathering of earthen site surfaces |

| Sources of Date | Search Category | Grouting Numerical Simulation | Overburden Grouting | Study on Fluid–Solid Coupling of Slurry Flow | Slurry Diffusion Model | Grouting Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNKI | Title/keyword/abstract | 1220 | 544 | 107 | 1179 | 231 |

| EI | Title/keyword/abstract | 2210 | 100 | 89 | 949 | 1253 |

| Web of Science | Topic | 2370 | 320 | 104 | 2606 | 1439 |

| Wanfang data | Topic | 1215 | 1000 | 262 | 1052 | 5035 |

| ASCE | Keyword | 3080 | 2140 | 531 | 1079 | 3106 |

| Elsevier | Keyword | 6920 | 777 | 10,452 | 76,046 | 8631 |

| John Wiley | Title/keyword/abstract | 2818 | 1096 | 8551 | 32,761 | 3503 |

| Springer | Title/keyword/abstract | 2974 | 222 | 2488 | 13,842 | 2551 |

| Type of Governing Equation | Basic Equation Combination | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seepage Field Governing Equation | Darcy’s Law + Mass Conservation Equation | It has a mature theoretical system and serves as the basis for seepage simulation. With a concise form, clear physical meaning, and high computational efficiency, it can quickly characterize the migration law of pore water or grout under saturated/unsaturated conditions. It is suitable for predicting the seepage velocity, water level change, and anti-seepage effect at the engineering scale, and its parameters are easy to obtain through on-site tests, resulting in strong engineering applicability [22]. | It relies on the continuous medium assumption, insufficiently characterizes the microscopic pore structure of highly discrete overburden, and has difficulty accurately reflecting the non-Darcy flow behaviors such as grout splitting and diffusion. Its prediction accuracy for seepage under complex working conditions is limited [23,24]. |

| Stress Field Governing Equation | Equilibrium Equation + Constitutive Equation + Geometric Equation | It can adapt to the mechanical properties of various overburden geotechnical materials (cohesive soil, sandy soil, crushed stone soil) through different constitutive models, effectively characterizing the foundation settlement, deformation coordination, and failure mechanism. As a core tool for analyzing overburden stability (such as bearing capacity after grouting reinforcement), it has rigorous calculation logic and its results can directly serve engineering design [25,26]. | The constitutive parameters have strong discreteness, and it has difficulty reflecting the influence of the mesoscopic structure of geotechnical materials (particle contact, pore evolution) on macroscopic mechanical response; convergence difficulties are prone to occur under large deformation or strong nonlinear working conditions, and its adaptability to complex loading paths is insufficient [27,28,29,30]. |

| Grout Diffusion Governing Equation | Solute Transport/Fluid Flow Equation | Focusing on the core grouting process, it can quantify the grout concentration distribution, diffusion range, and migration rate. Combined with grout properties (time-varying viscosity, bleeding, and consolidation), it can optimize key parameters such as the grouting pressure and hole spacing, providing theoretical support for technologies such as targeted grouting and segmented grouting and directly meeting practical engineering needs [31,32,33]. | It is necessary to simplify the grout–geotechnical interaction (such as ignoring the dynamic process of grout stone body blocking pores) and has poor adaptability to overburden heterogeneity; the parameters are significantly affected by the construction environment, making accurate value acquisition difficult, which easily leads to deviations between simulation results and on-site reality [14,34,35]. |

| Chemical Field Governing Equation | Reaction Kinetics Equation | It can reveal the chemical interaction between grout and overburden (ion exchange, cementation reaction, dissolution), quantify the long-term evolution law of geotechnical mechanical parameters (such as strength, permeability), and make up for the deficiency of pure mechanical simulation in predicting long-term stability, which is suitable for durability evaluation (such as foundation treatment in saline soil areas) [36]. | The reaction mechanism is complex, requiring a large number of chemical kinetic parameters that are difficult to obtain directly through tests; the calculation process involves multi-component transport and reaction coupling, resulting in a large computational load, high difficulty in collaborative solution with other physical fields, and reduced accuracy in engineering applications due to the simplified assumptions. |

| Acquisition Method | Parameter Types Obtainable | Advantages | Limitations | Grout Parameters | Geological Parameters | Common Tests/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Tests | Grout parameters, formation parameters | Controlled conditions, precise data, ability to obtain time-dependent parameters | Sample disturbance, scale limitations, cannot reflect in situ heterogeneity | Rheological parameters Setting time Hardened grout strength | Permeability coefficient Porosity Shear strength Particle size distribution | Permeability test Compression test Direct shear test Triaxial test Particle size analysis test |

| In situ Tests | Formation parameters | Avoids sampling disturbance, reflects real field conditions, obtains continuous profile data | Equipment limitations, limited data dimensions, limited adaptability to complex formations | / | Permeability coefficient Porosity Tensile strength Fracture density | Water pressure (Lugeon) test Grouting test Cone penetration test (CPT) Standard penetration test (SPT) Ground penetrating radar (GPR) Sonic logging |

| Inverse Analysis | Model parameters | Considers multiple influencing factors, corrects heterogeneous parameters, improves simulation accuracy | Relies on high-quality monitoring data, high computational complexity, prone to local optima | / | / | Data preprocessing Objective function construction Optimization algorithm selection Parameter sensitivity analysis |

| Method Category | Typical Software/Tools | Primary Application Scenarios | Diffusion Mode(s) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuum Methods | COMSOL, ABAQUS, PLAXIS 2D/3D, ANSYS Fluent | Homogeneous or low-fracture density overburden (e.g., sandy gravel, clay layers); shallow overburden grouting (hole depth ≤ 15 m); low-pressure grouting (<3 MPa); scenarios with high grout concentration | Permeation | High computational efficiency, intuitive simplified models; suitable for rapid assessment of grouting effectiveness; easy to handle macro-scale parameters | Cannot accurately depict discontinuous fracture characteristics; models may be oversimplified; poor adaptability to heterogeneous formations; simplistic treatment of time-dependent grout rheology. |

| Discrete Methods | PFC, UDEC, 3DEC | Grouting studies in layers with significant particle size variation, gravel layers, or crushed stone layers; high-fracture-density overburden (>12%); high-pressure injection (>4 MPa); scenarios involving high-yield-strength grouts; clogging, filtration failure, and channelized flow. | Permeation Fracturing Compaction -induced | Can realistically describe local channel flow, preferential flow paths, fracture initiation and propagation; accurately simulates fracture opening/closure due to grout pressure; can represent filtration and clogging effects in varied particle size distributions. | High computational complexity; massive computational load, difficult for large-scale site simulation; simulation of discontinuous fractures may overlook microstructural randomness; parameters (particle modulus, friction coefficient, interface parameters) are difficult to obtain. |

| Coupled Continuum–Discrete Methods | Fluent–EDEM, Abaqus–DEM, PFC–COMSOL | Mixed “permeation + local fracturing” diffusion mechanisms in overburden grouting; gravel/sand–gravel mixed layers, where particle skeleton and grout flow interact significantly; thermo-mechanical coupling during grout solidification; synergistic chemical grout hydration reaction and diffusion. | Permeation Fracturing Compaction -induced | Can comprehensively consider multiple influencing factors; improves simulation accuracy; suitable for parameter optimization under complex grouting conditions; simultaneously reflects macro-scale formation deformation and micro-scale fracture/channel formation. | High computational resource consumption; requires fine mesh/grid discretization; multi-field coupling may introduce additional errors; indirect coupling methods may have convergence issues. |

| Multi-scale Models | (µ-scale) LBM, PNM; (meso-scale) DEM, DFN; (macro-scale) COMSOL, ABAQUS, FLAC, PLAXIS | Heterogeneous overburden (e.g., sandy gravel layers with clay interbeds); ultra-deep overburden grouting (>150 m); rock masses with coexisting complex fractures and pores; scenarios requiring coordination between macro-scale curtain formation and micro-scale filling. | Permeation | Can bridge macro and micro characteristics; capable of capturing complex behaviors in heterogeneous overburden; suitable for simulating combined filling of large and micro fractures in sandy gravel layers. | Complex algorithms, high difficulty in developing cross-scale interfaces; long computation times, requiring high-performance computing platforms; relies on complex parameter settings across multiple software tools; multi-scale mapping algorithms are complex. |

| Stage | Evaluation Method | Scale | Advantages | Characteristic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During Grouting | Grouting machine parameters | Grouting pressure | Engineering | Core control parameter; directly controls slurry diffusion range; ensures filling compactness; prevents structural damage; optimizes construction process | Key parameter for controlling grouting quality |

| Slurry flow rate | Engineering | Core control parameter; controls total injection volume; evaluates formation permeability; allows dynamic adjustment of construction parameters; prevents equipment failure | Flow rate reflects injection speed and formation grout absorption capacity | ||

| Slurry density | Engineering | Core control parameter; ensures slurry stability; controls filling effect; prevents workmanship issues; optimizes resource utilization; guides field testing and mix proportion adjustment; enables real-time monitoring of slurry status; effectively controls fluidity | Directly reflects slurry concentration (e.g., water–cement ratio) | ||

| Formation monitoring | Pore pressure | Engineering | Prevents hydraulic fracturing and formation uplift; controls formation settlement induced by excess pore water pressure; quantifies slurry diffusion range and filling degree | Important basis for judging construction phase and completion conditions | |

| Formation uplift | Field | Ensures construction safety and structural stability; guides subsequent remedial measures | Exhibits hysteresis | ||

| Grout leakage | Engineering | Quantifies grouting influence range; verifies rock mass reinforcement effect | Exhibits hysteresis | ||

| Grouting duration | Engineering | Core control parameter; controls slurry diffusion and solidification; allows dynamic adjustment of completion timing; balances efficiency and quality; enables construction record traceability | Exhibits hysteresis | ||

| Post Grouting | In situ testing | Ultrasonic testing | Model/Component | Non-destructive, layered detection; evaluates improvement in rock mass integrity, compactness, and elastic modulus; increased wave velocity indicates fracture filling and enhanced consolidation | Susceptible to boundary condition interference |

| Geophysical exploration | Laboratory | Large-scale, non-destructive; integrates elastic wave CT, ground-penetrating radar, tomography, etc., to non-invasively detect slurry distribution, fracture filling, and rock mass integrity, e.g., elastic wave CT reveals inter-borehole wave velocity distribution, reflecting slurry diffusion range | Complex equipment, high cost | ||

| Water pressure test (Lugeon test) | Field | Simple operation, seepage prevention assessment; evaluates anti-seepage performance by measuring permeability (e.g., Lugeon value), core acceptance indicator for curtain grouting; reduced permeability indicates effective fracture sealing | Low resolution, requires verification | ||

| Laboratory testing | Dynamic triaxial test | Engineering | Quantitative dynamic performance: measures dynamic characteristic parameters (e.g., shear modulus, damping ratio) of grouted rock mass under dynamic loading, assesses liquefaction resistance and dynamic stability | Cannot reflect mechanical properties | |

| Core inspection | Field | Accurate results; direct observation of filling compactness, cementation quality, and fracture closure in cores; most intuitive verification method, e.g., bonding degree between cement stone and surrounding rock indicates bond strength | Destructive, localized | ||

| Triaxial test | Comprehensive | Measures compressive strength, deformation modulus, and other mechanical parameters of grouted rock mass through triaxial compression tests on core samples, evaluates improvement in mechanical properties | Relies on expert experience | ||

| Multi-criteria decision methods | Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation | Comprehensive | Handles multi-index fuzziness; integrates multi-dimensional indicators (permeability, rock mass integrity, fracture sealing degree, etc.); quantifies weights through Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and fuzzy mathematics for systematic grouting effect evaluation | Requires substantial data support | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, P.; Zhao, W.; Qu, L.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, P. Review of Numerical Simulation of Overburden Grouting in Foundation Improvement. Geotechnics 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010003

Guo P, Zhao W, Qu L, Li X, Ma Y, Li P. Review of Numerical Simulation of Overburden Grouting in Foundation Improvement. Geotechnics. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Pengfei, Weiquan Zhao, Linxiu Qu, Xifeng Li, Yahui Ma, and Pan Li. 2026. "Review of Numerical Simulation of Overburden Grouting in Foundation Improvement" Geotechnics 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010003

APA StyleGuo, P., Zhao, W., Qu, L., Li, X., Ma, Y., & Li, P. (2026). Review of Numerical Simulation of Overburden Grouting in Foundation Improvement. Geotechnics, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010003