Response of Well-Graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures in Triaxial Compression: Application of a Critical State-Based Generalized Plasticity Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Well-Graded Gravel Rubber Mixtures (wgGRMs)

2.1. Physical Properties

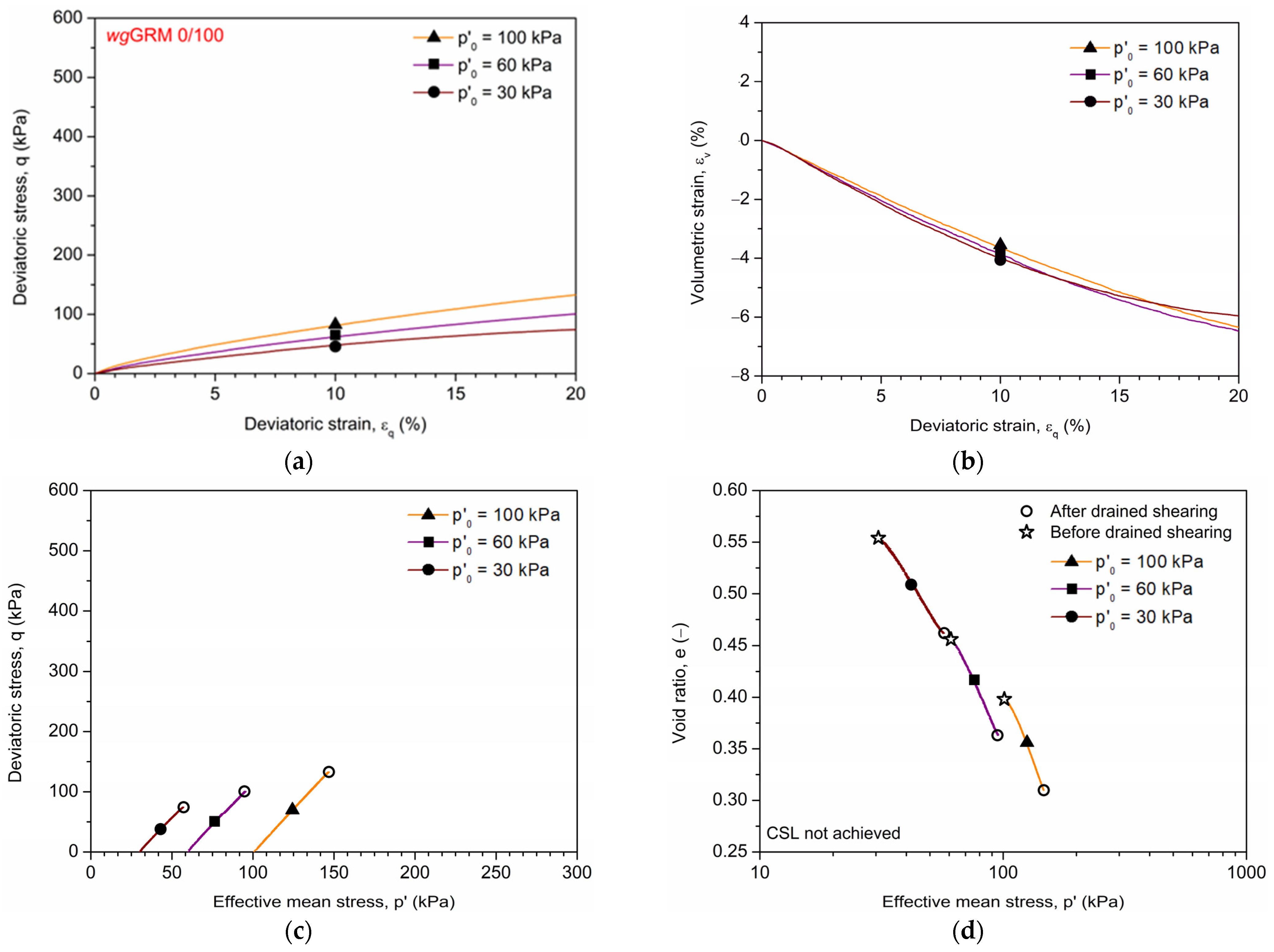

2.2. Mechanical Properties

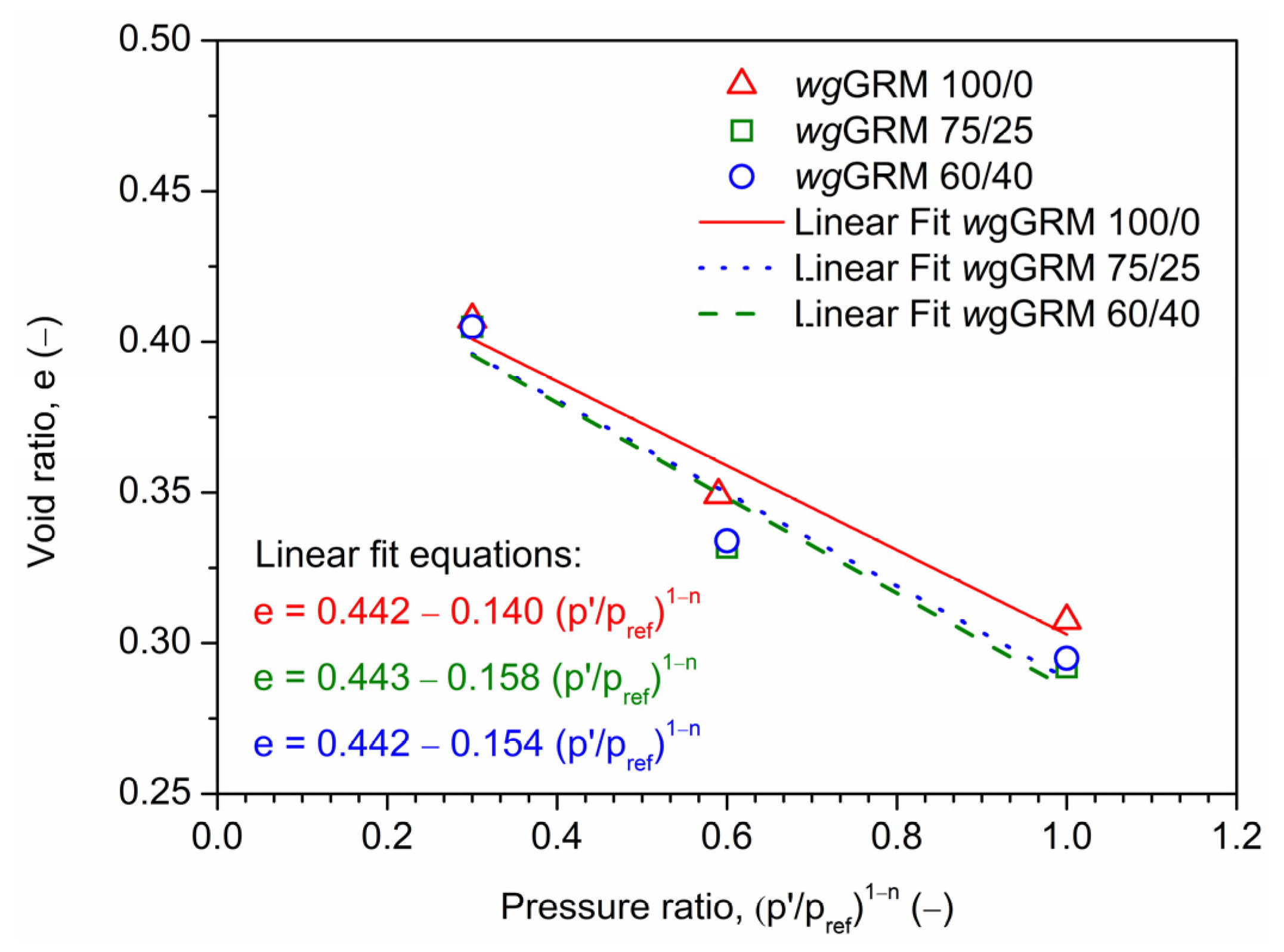

2.3. Insights into the Potential Critical State Behavior of wgGRMs

3. Constitutive Model

3.1. Fundamental Equations

3.1.1. Elastic and Plastic Strains

3.1.2. Stress–Dilatancy Relationship (Flow Rule)

3.1.3. Plastic Flow (Loading Direction)

3.1.4. Plastic Modulus

3.2. Calibration and Determination of Model Parameters

- The critical void ratio at p′ = 1 kPa: eΓ(fVRC) = 0.0001(VRC)2 − 0.006(VRC) + 0.833

- The slope of the CSS in the e-p′ plane: λ* = 0.092 (constant)

- The slope of CSS in the q-p′ plot: M*css(fVRC) = −0.0002(VRC)2 + 0.0068(VRC) + 1.63

4. Simulation Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- describe the peak stress and post-peak softening in wgGRMs;

- capture the progressive reduction in strength and enhanced ductility with increasing VRC;

- reproduce the shift from dilative to contractive responses with increasing confining pressure;

- predict the stress–dilatancy relationships and the transition from contractive to dilative phases, aligning closely with observed critical state conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Particle Size Ratio |

| CSL | Critical State Line |

| CSS | Critical State Surface |

| Cc,G, Cu,R | Curvature coefficient of the well-graded gravel and granulated rubber, respectively |

| Cu,G, Cu,R | Uniformity coefficient of the well-graded gravel and granulated rubber, respectively |

| D50,G, D50,R | Mean grain size of the well-graded gravel and granulated rubber, respectively |

| df | Loading direction parameter |

| dg | Dilatancy |

| D | Dilatancy ratio, being equal to dεq/dεv |

| Dc | Degree of compaction |

| DEM | Discrete Element Method |

| dε, dσ | Strain and stress increment, respectively |

| dεq, dεv | Deviatoric strain and volumetric strain increments, respectively |

| e | Void ratio |

| e0 | Initial void ratio |

| ecs | Void ratio at critical state |

| ELTs | End-of-Life Tires |

| emax, emin | Maximum void ratio and minimum void ratio, respectively |

| eΓ | Critical void ratio at a reference pressure of 1 kPa |

| FE | Finite Element |

| G | Shear modulus |

| GRMs | Gravel–Rubber Mixtures |

| GW | Well-graded gravel |

| Gs,G, Gs,R | Specific gravity of the well-graded gravel and granulated rubber, respectively |

| H | Plastic modulus |

| h0 | Model parameter for hardening |

| HS-small | Hardening soil model with small strain stiffness |

| K | Bulk modulus |

| Mcss* | Slope of CSS in the p′-q plot |

| Mcss | Slope of CSL in the p′-q plot |

| Me, Mep | Elastic and elasto-plastic stiffness matrices, respectively |

| mg | Plastic flow direction vector |

| mq, mv | Components of plastic flow direction vectors |

| n | Material constant |

| nf | Loading direction vector |

| nq, nv | Components of loading direction vectors |

| p′ | Effective mean stress |

| p0′ | Effective confining pressures |

| patm | Atmospheric pressure (=100 kPa) |

| pref | Reference confining pressure |

| PT | Phase Transformation |

| q | Deviatoric Stress |

| qcs | Deviatoric Stress at the critical state |

| SoRMs | Soil–Rubber Mixtures |

| TxCD | Isotropically consolidated drained monotonic triaxial |

| VRC | Volumetric Rubber Content |

| wgGRMs | well-graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures |

| ε1, ε2, ε3 | Major, intermediate, and minor principal strains, respectively |

| εq, εeq, εpq | Total, elastic, and plastic deviatoric strains, respectively |

| εv, εev, εpv | Total, elastic, and plastic volumetric strains, respectively |

| η | Stress ratio |

| ηpk* | Virtual peak stress ratio |

| ηpt | Stress ratio at the phase transformation |

| ηf | Model parameters for plastic potential |

| κ | Swelling–recompression index |

| λ | Slope of the CSL in the plane (p′/pref)1−n-e |

| λ* | Slope of the CSS in the p′-e-VRC space |

| μf | Model parameters for plastic potential |

| μg | Model parameters for dilatancy |

| μpk | Model parameters for hardening |

| ν | Poisson’s ratio |

| ξf | Model parameters for plastic potential |

| ξg | Model parameters for dilatancy |

| σ’1, σ’2, σ’3 | Effective major, intermediate, and minor principal stresses, respectively |

| ψ* | State parameter |

| ψpk* | State parameter at the peak of deviatoric stress |

| ψpt* | State parameter at the phase transformation |

References

- Han, B.; Kumar, D.; Pei, Y.; Norton, M.; Adams, D.A.; Khoo, S.; Kouzani, A.Z. Sustainable transformation of end-of-life tyres into value-added products using thermochemical processes. Carbon Res. 2024, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Morera, J.; Verdejo, R.; López-Manchado, M.A.; Santana, M.H. Sustainable mobility: The route of tires through the circular economy model. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WBCSD World Business Council for Sustainable Development Managing End-of-Life Tires. Available online: https://docs.wbcsd.org/2019/12/Global_ELT_Management%E2%80%93A_global_state_of_knowledge_on_regulation_management_systems_impacts_of_recovery_and_technologies.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Lee, J.; Salgado, R.; Bernal, A.; Lovell, C. Shredded tires and rubber-sand as lightweight backfill. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1999, 125, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masad, E.; Taha, R.; Ho, C.; Papagiannakis, T. Engineering properties of tire/soil mixtures as a lightweight fill material. Geotech. Test. J. 1996, 19, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.B.; Krishna, A.M. Recycled Tire Chips Mixed with Sand as Lightweight Backfill Material in Retaining Wall Applications: An Experimental Investigation. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2015, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Hazarika, H. Improvement of shallow foundation using non-liquefiable recycled materials. Jpn. Geotech. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2016, 2, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, H.; Pasha, S.M.K.; Ishibashi, I.; Yoshimoto, N.; Kinoshita, T.; Endo, S.; Karmoka, A.K.; Hitosugi, T. Tire-chip reinforced foundation as liquefaction countermeasure for residential buildings. Soils Found. 2020, 60, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, G.; Bhattacharya, S. Experimental study on sand-tire chip mixture foundations acting as a soil liquefaction countermeasure. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 4037–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H. Seismic isolation by rubber–soil mixtures for developing countries. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2008, 37, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Lo, S.H.; Xu, X.; Neaz Sheikh, M. Seismic isolation for Low-To-Medium-Rise buildings using granulated rubber–soil mixtures: Numerical study. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 41, 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H. Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI): State of the art. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 198, 109627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H. Analytical design models for geotechnical seismic isolation systems. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3881–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitilakis, D.; Anastasiadis, A.; Vratsikidis, A.; Kapouniaris, A.; Massimino, M.R.; Abate, G.; Corsico, S. Large-scale field testing of geotechnical seismic isolation of structures using gravel-rubber mixtures. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 50, 2712–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanya, J.S.; Boominathan, A.; Banerjee, S. Response of low-rise building with geotechnical seismic isolation system. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 136, 106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Tran, D.P.; Hung, W.Y.; Pitilakis, K.; Gad, E.F. Performance of geotechnical seismic isolation system using rubber-soil mixtures in centrifuge testing. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 50, 1271–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Fiamingo, A.; Massimino, M.R.; Pitilakis, D. FEM investigation of full-scale tests on DSSI, including gravel-rubber mixtures as geotechnical seismic isolation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 172, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Palermo, A.; Banasiak, L.; Tasalloti, A.; Granello, G.; Hernandez, E. Seismic response of low-rise buildings with eco-rubber geotechnical seismic isolation (ERGSI) foundation system: Numerical investigation. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3797–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D.; Alzabeebee, S. Seismic fragility assessment of geotechnical seismic isolation (GSI) for bridge configuration. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3969–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. Seismic resilience of bridges isolated with traditional and geotechnical seismic isolation (GSI). Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3521–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. Assessment of Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI) as a Mitigation Technique for Seismic Hazard Events. Geosciences 2020, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. Preliminary Assessments of Geotechnical Seismic Isolation Design Properties. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. Fragility Assessment of Geotechnical Seismic Isolated (GSI) Configurations. Energies 2021, 14, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. Assessment on geotechnical seismic isolation (GSI) on bridge configurations. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2017, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D.; Chiaro, G.; Palermo, A.; Banasiak, L.; Tsang, H.H. Energy dissipation efficiency of geotechnical seismic isolation with gravel-rubber mixtures: Insights from FE nonlinear numerical analysis. J. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 28, 2422–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Tran, D.P.; Gad, E.F. Serviceability performance of buildings founded on rubber–soil mixtures for geotechnical seismic isolation. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2023, 24, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleska, T.; Beben, D.; Nowacka, J.; Fiamingo, A.; Massimino, M.R. Seismic finite element method simulation of a soil-steel bridge with a gravel-rubber mix. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Bridge Maintenance, Safety and Management, IABMAS 2024; Jensen, J.S., Frangopol, D.M., Schmidt, J.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edil, T.B.; Park, J.K.; Kim, J.Y. Effectiveness of scrap tire chips as sorptive drainage material. J. Environ. Eng. 2004, 130, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.Y.; Tsang, H.H. A comparative life cycle assessment of recycled tire rubber applications in sustainable earthquake-resistant construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 211, 107860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasalloti, A.; Chiaro, G.; Murali, A.; Banasiak, L.; Palermo, A.; Granello, G. Recycling of end-of-life tires (ELTs) for sustainable geotechnical applications: A New Zealand perspective. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S.M.K.; Hazarika, H.; Yoshimoto, N. Physical and mechanical properties of Gravel-Tire Chips Mixture (GTCM). Geosynth. Int. 2019, 26, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xie, K.; Guo, Z.; Wang, P. Experimental investigation and multivariable prediction model of the compressibility of fine gravel-rubber mixtures considering particle size effect. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 483, 141759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Chiaro, G.; Fiamingo, A. Laboratory Tests on Gravel-Rubber Mixtures (GRM): FEM Modelling Versus Experimental Observations. In National Conference of the Researchers of Geotechnical Engineering, CNRIG 2023; Ferrari, A., Rosone, M., Ziccarelli, M., Gottardi, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Vrettos, C. Effect of layering and pre-loading on the dynamic properties of sand-rubber specimens in resonant column tests. Acta Geotech. 2025, 20, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, E.G.; Hosseininia, E.S. Seismic performance of rubber-sand mixture as a geotechnical seismic isolation system using shaking table test. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 177, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, F.; Bin, J.; He, J. Rubber-sand infilled soilbags as seismic isolation cushions: Experimental validation. Geosynth. Int. 2025, 32, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.Y.; Sutter, K.G. Dynamic properties of granulated rubber/sand mixtures. Geotech. Test. J. 2000, 23, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera Perez, J.C.; Kwok, C.Y.; Senetakis, K. Micromechanical analyses of the effect of rubber size and content on sand-rubber mixtures at the critical state. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera Perez, J.C.; Kwok, C.Y.; Senetakis, K. Investigation of the micro-mechanics of sand–rubber mixtures at very small strains. Geosynth. Int. 2017, 24, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Cui, L.; Zuo, X.; Wang, L. Dynamic behaviour of pipe protected by rubber–soil mixtures. Geosynth. Int. 2023, 30, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, J.R.; Evans, T.M. Sand–rubber mixtures: Experiments and numerical simulations. Can. Geotech. J. 2008, 45, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Santamarina, J.C. Sand–rubber mixtures (large rubber chips). Can. Geotech. J. 2008, 45, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hou, S.; Cao, X.; Tsang, H.H. Direct shear tests on the effects of displacement rate and particle size ratio on the shear behavior of fine gravel-rubber mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 476, 141263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.; Chiaro, G.; Vinod, J.S.; Tasalloti, A.; Allulakshmi, K. Direct shear behavior of gravel-rubber mixtures: Discrete element modeling and microscopic investigations. Soils Found. 2022, 62, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Tasalloti, A.; Palermo, A.; Banasiak, L. Small-strain shear stiffness and strain-dependent dynamic properties of gravel-rubber mixtures. In Proceedings of 17th Symposium on Earthquake Engineering; Shrikhande, M., Agarwal, P., Kumar, P.C.A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 331, pp. 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitilakis, D.; Anastasiadis, A.; Vratsikidis, A.; Kapouniaris, A. Configuration of a gravel-rubber geotechnical seismic isolation system from laboratory and field tests. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 178, 108463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistolas, G.A.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Dynamic properties of gravel–recycled rubber mixtures: Resonant column and cyclic triaxial tests. In Geotechnical Engineering for Infrastructure and Development: XVI European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering; Winter, M.G., Smith, D.M., Eldred, P.J.L., Toll, D.G., Eds.; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistolas, G.A.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Dynamic behaviour of granular soil materials mixed with granulated rubber: Effect of rubber content and granularity on the small-strain shear modulus and damping ratio. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistolas, G.A.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Dynamic behaviour of granular soil materials mixed with granulated rubber: Influence of rubber content and mean grain size ratio on shear modulus and damping ratio for a wide strain range. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2018, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vratsikidis, A.; Tsinaris, A.; Kapouniaris, A.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, D.; Pitilakis, K. Full-Scale Testing of a Structure on Improved Soil Replaced with Rubber–Gravel Mixtures. In Advances in Sustainable Construction and Resource Management. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Hazarika, H., Madabhushi, G.S.P., Yasuhara, K., Bergado, D.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; Volume 144, pp. 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetakis, K.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Dynamic properties of dry sand/rubber (SRM) and gravel/rubber (GRM) mixtures in a wide range of shearing strain amplitudes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2012, 33, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, A.; Senetakis, K.; Pitilakis, K. Small strain shear modulus and damping ratio of sand-rubber and gravel-rubber mixtures. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2012, 30, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vratsikidis, A.; Pitilakis, D. Field testing of gravel-rubber mixtures as geotechnical seismic isolation. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3905–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamingo, A.; Chiaro, G.; Murali, A.; Massimino, M.R. Geotechnical characterization of soil-rubber mixtures with well-graded gravel. Geosynth. Int. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamingo, A.; Abate, G.; Chiaro, G.; Massimino, M.R. Small-strain stiffness and dynamic properties of well-graded gravel–rubber mixtures. Geotech Lett. 2025, 15, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A. Characteristics and Performance of Gravel-Rubber Mixtures as Geotechnical Seismic Isolation for Lightweight Residential Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2025; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, G.; Caruso, C.; Massimino, M.R.; Maugeri, M. Validation of a new soil constitutive model for cyclic loading by fem analysis. Solid Mech. Appl. 2007, 146, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Massimino, M.R.; Maugeri, M. Numerical modelling of centrifuge tests on tunnel–soil systems. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 1927–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surarak, C.; Likitlersuang, S.; Wanatowski, D.; Balasubramaniam, A.; Oh, E.; Guan, H. Stiffness and strength parameters for hardening soil model of soft and stiff Bangkok clays. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkarak, R.; Likitlersuang, S.; Jongpradist, P.; Jamsawang, P. Strength and stiffness parameters for hardening soil model of rockfill materials. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, D.; Mohamad Ismail, M.A.; Mohammad Zaki, M.F.; Zainal Abidin, M.H. Calibration of stiffness parameters for Hardening Soil Model in residual soil from Kenny Hill Formation. Bull. Geol. Soc. Malays. 2019, 67, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Indraratna, B.; Tasalloti, A. Predicting the behaviour of coal wash and steel slag mixtures under triaxial conditions. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamingo, A.; Abate, G.; Chiaro, G.; Massimino, M.R. HS-small constitutive model for innovative geomaterials: Effectiveness and limits. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04024118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, T. Small-Strain Stiffness of Soil Sand Its Numerical Consequences. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut für Geotechnik, University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, T.; Vermeer, P.A.; Schwab, R. A small-strain overlay model. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2009, 33, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.I.; Yang, S. Unified sand model based on the critical state and generalized plasticity. J. Eng. Mech. 2006, 132, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D2487-17; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- D6270-17; Standard Practice for Use of Scrap Tires in Civil Engineering Applications (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- Lee, C.; Truong, Q.H.; Lee, W.; Lee, J.S. Characteristics of rubber-sand particle mixtures according to size ratio. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2010, 22, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiak, L.; Chiaro, G.; Palermo, A.; Granello, G. Environmental implications of the recycling of end-of-life tires in seismic isolation foundation systems. In Advances in Sustainable Construction and Resource Management; Hazarika, H., Madabhushi, G.S.P., Yasuhara, K., Bergado, D.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; Volume 144, pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bo, M.W.; Leong, E.C.; Soltani, A.; Banasiak, L.; O’Kelly, B.C.; Cheng, Z.; Nyunt, T.T.; Chiaro, G.; Palermo, A.; et al. Material recovery from waste rubber tyres and their geoenvironmental utilisation: A review. Environ. Geotech. 2025, 12, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZS 4402; Methods of Testing Soils for Civil Engineering Purposes. Standards Association of New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 1986.

- D4254-16; Standard Test Methods for Minimum Index Density and Unit Weight of Soils and Calculation of Relative Density. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- D698-12; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12 400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Ladd, R.S. Preparing test specimens using undercompaction. Geotech. Test. J. 1978, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, K.H.; Scholfield, A.N.; Wroth, C.P. On the yielding of soils. Géotechnique 1958, 8, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholfield, A.N.; Wroth, P. Critical State Soil Mechanics; McGraw-Hill Book, Co.: London, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Vesic, A.S.; Clough, G.W. Behaviour of granular materials under high stresses. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1968, 94, 661–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, A.; Coop, M.R.; Lancellotta, R. Influence of grading on the mechanical behaviour of Stava tailings. Géotechnique 2011, 61, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Sun, Q.D.; Nimbalkar, S. Observed and predicted behaviour of rail ballast under monotonic loading capturing particle breakage. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modoni, G.; Koseki, J.; Anh Dan, L.Q. Cyclic stress–strain response of compacted gravel. Geotechnique 2011, 61, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Indraratna, B.; Vinod, J.S. Behavior of steel furnace slag, coal wash, and rubber crumb mixtures with special relevance to stress–dilatancy relation. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 2018, 30, 04018276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Chiaro, G.; Wilson, T.; Stringer, M. Monotonic drained and undrained shear behaviors of compacted slightly weathered tephras from New Zealand. Geotechnics 2024, 4, 843–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Wang, Y. Linear representation of steady-state line for sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 1998, 124, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Mroz, Z. Generalized plasticity formulation and applications to geomechanics. In Mechanics of Engineering Materials; Desai, C.S., Gallagher, R.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 655–679. [Google Scholar]

- Mroz, Z.; Zienkiewicz, O.C. Uniform formulation of constitutive equations for clay and sand. In Mechanics of Engineering Materials; Desai, C.S., Gallagher, R.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 415–450. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, M.; Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Chan, A.H.C. Generalized plasticity and the modeling of soil behavior. Int. J. Numer. Analyt. Meth. Geomech. 1990, 14, 151–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanal, D.; Merodo, J.A.F.; Pastor, M. Generalized plasticity state parameter-based model for saturated and unsaturated soils. Part 1: Saturated state. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2011, 35, 1347–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, H.G.; Davis, E.H. Elastic Solutions for Soil and Rock Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Sydney, Australia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Been, K.; Jefferies, M.G. A state parameter for sands. Géotechnique 1985, 35, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzari, M.T.; Dafalias, Y.F. A critical state two-surface plasticity model for sands. Géotechnique 1997, 47, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Dafalias, Y.F. Dilatancy for cohesionless soils. Géotechnique 2000, 50, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Koseki, J.; De Silva, L.I.N. A density- and stress-dependent elasto-plastic model for sands subjected to monotonic torsional shear loading. Geotech. Eng. J. 2013, 44, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

| Soil Parameter | wgGRM 100/0 | wgGRM 75/25 | wgGRM 60/40 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confining Pressure, p0′ (kPa) | 100 | 60 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 30 |

| Elastic | |||||||||

| κ (−) | 0.00180 | 0.00256 | 0.00182 | 0.00923 | 0.01023 | 0.00844 | 0.02137 | 0.01596 | 0.01064 |

| ν (−) | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.42 | ||||||

| Critical State Surface (CSS) | |||||||||

| eΓ (−) | 0.833 | 0.762 | 0.791 | ||||||

| λ* (−) | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.092 | ||||||

| Mcss* (−) | 1.625 | 1.494 | 1.348 | ||||||

| Dilatancy | |||||||||

| ξg (−) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||||||

| μg (−) | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Loading Direction | |||||||||

| ξf (−) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||||||

| μf (−) | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Plastic Modulus | |||||||||

| h0 (kPa) | 2500 | 4000 | 10,000 | 1800 | 1200 | ||||

| μpk (−) | 28 | 18 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| Soil Parameter | Confining Pressure, p′0 (kPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 60 | 30 | |

| Elastic | |||

| κ (−) | 10−5(VRC)2 − 2(VRC)10−5 + 0.002 | 2 × 10−6(VRC)2 − 3(VRC)10−4 + 0.003 | −3 × 10−6(VRC)2 + 3(VRC)10−4 + 0.003 |

| ν (−) | −2 × 10−5(VRC)2 + 0.0024(VRC) + 0.35 | ||

| Critical State Surface (CSS) | |||

| eΓ (−) | 0.0001(VRC)2 − 0.006(VRC) + 0.833 | ||

| λ* (−) | 0.092 | ||

| Mcss* (−) | −0.0002(VRC)2 + 0.0068(VRC) + 1.63 | ||

| Dilatancy | |||

| ξg (−) | −0.0002(VRC)2 + 0.022(VRC) + 0.7 | ||

| μg (−) | 0.001(VRC)2 − 0.07(VRC) + 7 | −0.001(VRC)2 + 0.07(VRC) + 5 | −0.002(VRC)2 + 0.13(VRC) + 4 |

| Loading Direction | |||

| ξf (−) | −0.0002(VRC)2 + 0.022(VRC) + 0.7 | ||

| μf (−) | 2 | ||

| Plastic Modulus | |||

| h0 (kPa) | −0.3(VRC)2 − 20.5(VRC) + 2500 | 1.2(VRC)2 − 118(VRC) + 4000 | 7.2(VRC)2 − 508(VRC) + 10,000 |

| μpk (−) | 0.014(VRC)2 − 0.91(VRC) + 28 | 0.008(VRC)2 − 0.52(VRC) + 18 | 0.003(VRC)2 − 0.2(VRC) + 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiamingo, A.; Chiaro, G. Response of Well-Graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures in Triaxial Compression: Application of a Critical State-Based Generalized Plasticity Model. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040075

Fiamingo A, Chiaro G. Response of Well-Graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures in Triaxial Compression: Application of a Critical State-Based Generalized Plasticity Model. Geotechnics. 2025; 5(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiamingo, Angela, and Gabriele Chiaro. 2025. "Response of Well-Graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures in Triaxial Compression: Application of a Critical State-Based Generalized Plasticity Model" Geotechnics 5, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040075

APA StyleFiamingo, A., & Chiaro, G. (2025). Response of Well-Graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures in Triaxial Compression: Application of a Critical State-Based Generalized Plasticity Model. Geotechnics, 5(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040075