Abstract

This study investigates how land access, inheritance expectations, and socio-economic conditions influence migration intentions of rural youth in central Vietnam. Drawing on survey data from 200 young respondents and employing logistic regression analysis, the research reveals that youth with higher levels of education and income exhibit a greater propensity to migrate in pursuit of improved livelihoods. Male respondents were significantly more likely to migrate, reflecting gender norms and unequal access to opportunities. Crucially, secure land tenure—measured through formal land titles and perceived inheritance rights—was strongly associated with lower migration intentions. Conversely, tenure insecurity emerged as a significant push factor, undermining youth confidence in long-term rural investment and contributing to land use instability. This study argues that secure land access is not only vital for sustaining rural livelihoods but also foundational for youth and women’s engagement, socio-economic stability, and long-term community resilience. From this viewpoint, this study highlights the need for youth-inclusive land reforms, the promotion of rural entrepreneurship, and expanded access to vocational training as critical policy interventions.

1. Introduction

Globally, land is not only a critical economic asset but also a key determinant of individual and collective identities, as well as a foundational element of social organization [1]. It underpins the cultural, economic, and social structures of rural communities, serving both symbolic and material functions [2]. Land reflects and reinforces social relations—within communities and between communities and the state—making it a central site of both practical disputes and symbolic struggles. In many agrarian societies, land is regarded as “the source of life of the people” [3], and secure access to land is closely tied to food security, cultural preservation, and the continuity of community identity [4]. Despite its importance, access to land is increasingly under pressure. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and shifting land use policies have contributed to declining land availability—especially for poor households and rural youth [5,6]. This makes secure and equitable land access a critical issue for sustainable development and social stability.

The concept of access—derived from the Latin accessus, meaning “approach” or “entrance”—has evolved over centuries [7]. Initially associated with property and inheritance rights in the legal systems of the 17th and 18th centuries [8], it later expanded in sociological discourse during the 1980s and 1990s to refer to unequal access to education, healthcare, and political participation [9]. In resource governance, the term has shifted focus from ownership to the right to use and benefit from resources, often managed communally or by the state [10]. In this context, land access refers to the ability of individuals or groups to use, control, and derive benefits from land—whether through ownership, leasing, or shared use—within legal, institutional, and cultural frameworks. For rural households, secure land access supports livelihoods, food security, and economic stability, particularly in farming communities where land is central to crop cultivation, livestock rearing, and income generation [11]. Secure tenure also enables long-term investment, adoption of sustainable practices, and resilience to climate change. Moreover, equitable access to land strengthens women’s empowerment and promotes gender equality in decision making and household welfare [12].

In Vietnam, land is legally owned by “the entire people,” with the State acting as the representative owner [13]. The 2024 Land Law reinforces this principle and affirms that all citizens have the right to access land-related information, including land use plans, statistics, inventories, and decisions on land allocation and leasing [14]. Agriculture remains a vital pillar of Vietnam’s economy, particularly in rural areas. In 2022, agricultural exports were valued at approximately USD 55 billion, supporting millions of smallholder farmers and contributing significantly to both employment and GDP [2]. However, the country faces serious challenges related to land availability. With an average agricultural land area of just 0.25 hectares per person, Vietnam ranks among the lowest in the world [15]. The average farm size per household is only 0.156 hectares, considerably smaller than that of neighboring countries such as Thailand and Cambodia [16]. As a result, farming in Vietnam remains highly fragmented and small scale.

Over the past decade, rapid urbanization has intensified land pressure. Between 2010 and 2023, the urbanization rate increased from 30.5% to 42%, leading to the annual loss of nearly 100,000 hectares of agricultural land—amounting to approximately 1 million hectares over ten years [17,18]. Meanwhile, only approximately 400,000 agricultural workers exit the sector each year, leaving many to continue farming under increasingly constrained conditions [17]. These trends have led to land scarcity, rising production costs, difficulties in adopting modern technology, and a widening rural–urban divide. Land disputes have also become more frequent. Vietnam is home to 22.1 million young people, accounting for 22.5% of the population and 36% of the labor force, with approximately 60% residing in rural areas [19]. For most rural youth, land access is gained through inheritance, family transfers, or informal rental arrangements. However, shrinking landholdings, unclear inheritance prospects, and institutional barriers have pushed many young people toward precarious farming or pulled them toward non-agricultural employment and migration to urban areas.

In this context, understanding youth perspectives on land tenure security is critical. Improving access to land is a priority because land use rights are the basis for making investment decisions [20]. Secure land access can also offer a foundation for stable livelihoods, reduce migration pressures, and enhance rural development [5,6,7]. Vietnamese scholars have increasingly emphasized the need for youth-centered research, particularly among vulnerable groups such as rural women, in light of the rapid environmental and political changes affecting land use. Therefore, this study aims to:

- (1)

- Examine how rural youth perceive land tenure security in relation to their economic prospects and long-term aspirations;

- (2)

- Investigate the extent to which inheritance, leasing opportunities, and institutional constraints shape their decisions to stay in agriculture or migrate;

- (3)

- Propose policy and practical recommendations to support sustainable rural development and promote youth inclusion in land governance.

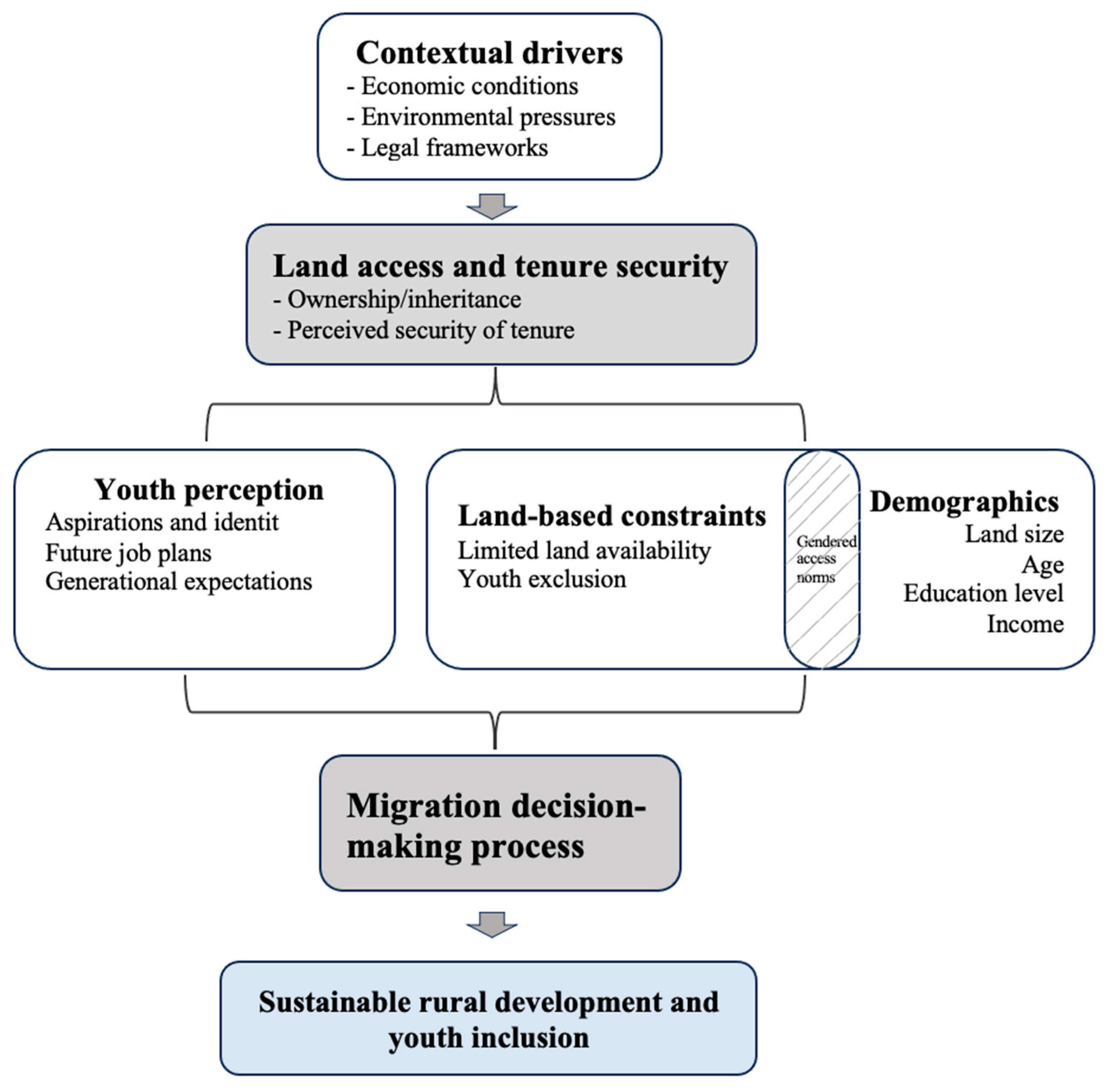

Conceptual Framework: Land Tenure and Migration Decisions

This study conceptualizes the relationship between land tenure insecurity and youth migration through an integrated framework that captures the interaction of structural, institutional, and individual-level factors (see Figure 1). Central to this framework is the understanding that land is not merely an economic asset but a cornerstone of rural youth’s identity, security, and future livelihood prospects.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of land tenure and migration decisions.

At the macro level, contextual drivers—including economic conditions and legal frameworks—form the broader setting within which land access and migration decisions are made [21,22]. These factors shape rural livelihoods and influence how young people perceive the viability of remaining in or departing from their communities. Within this context, state policies and institutional arrangements, including informal social contracts, play a critical role. For instance, land reforms that overlook the specific needs of youth have been associated with rising migration in Sub-Saharan Africa, whereas initiatives that enhance youth access to land, credit, and agricultural training have been shown to reduce migration intentions [5,23]. At the meso level, household and community dynamics shape both the actual and perceived security of land tenure. Even in countries like Ghana, where land registration is standardized, regional disparities persist due to historical and cultural differences [24]. Elements such as legal ownership, inheritance rights, and perceptions of tenure security significantly influence young people’s willingness to engage in land-based livelihoods [22,23,24]. In Central Vietnam, for example, land tenure is often complicated by overlapping statutory and customary claims, as well as ambiguous legal definitions—leading to uncertain or restricted access for rural youth [25,26].

Demographic characteristics, such as land size, age, gender, education level, and income, intersect with these tenure conditions [7,21,27,28,29,30,31,32]. For instance, youth from land-rich households may choose to stay and invest in farming, while those from land-poor families are more likely to migrate as a means of income diversification and risk reduction [7]. Similarly, Bezu and Barrett argue that land-rich households are less likely to diversify away from agriculture [27]. Landless or near-landless households are more likely to view migration as a pathway to diversify income and reduce vulnerability to economic shocks [21]. In Southeast Asia, youth with secure land rights often opt for seasonal or temporary migration to supplement agricultural activities rather than permanent migration [28]. Age is linked to past experience, and as Deininger and Jin found, past land redistribution and the resulting decline in tenure security significantly reduced investment in agriculture [29]. Gendered norms also play a significant role: in many contexts, women and girls face systemic barriers to land ownership or inheritance, thereby limiting their options and often leading to migration for low-wage, informal employment [30]. In Mexico, Kanaiaupuni found that the likelihood of migration decreases with each level of education in men, while the risk increases with higher levels of education in women [31]. Alhola and Gwaindepi observed that female landowners, especially those without title deeds, reported significantly lower rights to sell or use their land as collateral compared to their male counterparts [21].

At the micro level, youth perceptions and aspirations are crucial to migration decision making. Young people’s visions for their future—shaped by educational goals, career ambitions, and generational expectations—inform how they interpret opportunities available in their local contexts [33,34]. When these aspirations are incompatible with the realities of rural land access, migration becomes an attractive alternative. Empirical studies support this dynamic. In Senegal, land inheritance has been linked to reduced migration and lower participation in non-agricultural employment among youth with clearly defined land responsibilities [35]. Historical evidence from Norway similarly suggests that youth expecting to inherit land—based on birth order and family roles—were less likely to migrate [36]. In Ghana, Alhola and Gwaindepi found that youth with formal land titles were more likely to perceive themselves as having the right to sell land or use it as collateral, thereby influencing their migration choices [21]. Conversely, land-based constraints—such as limited availability, youth exclusion from ownership, and restricted roles in land-related decision making—function as direct push factors [37]. In certain communities, fears of land confiscation, especially when young people shift their labor away from agriculture, further discourage livelihood diversification and reinforce the migration imperative [38].

The variables anticipated to influence the migration decisions of Vietnamese youth are presented in Table 1. Although each factor may exert an independent effect, they interact and converge within the broader decision-making process, wherein youth assess the trade-offs between remaining in their communities and migrating elsewhere. Migration, therefore, is not solely an economic necessity but a strategic and adaptive response to land ownership stability, constrained opportunities, and structural inequalities. By embedding land tenure within a broader socio-economic and institutional context, this framework emphasizes the need for inclusive and gender-sensitive land governance as a key component of rural development strategies. Enhancing land access and tenure security for youth is essential not only to reduce involuntary migration but also to promote sustainable livelihoods and long-term rural resilience.

Table 1.

Determinants of youth migration decisions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study in Hue, Vietnam

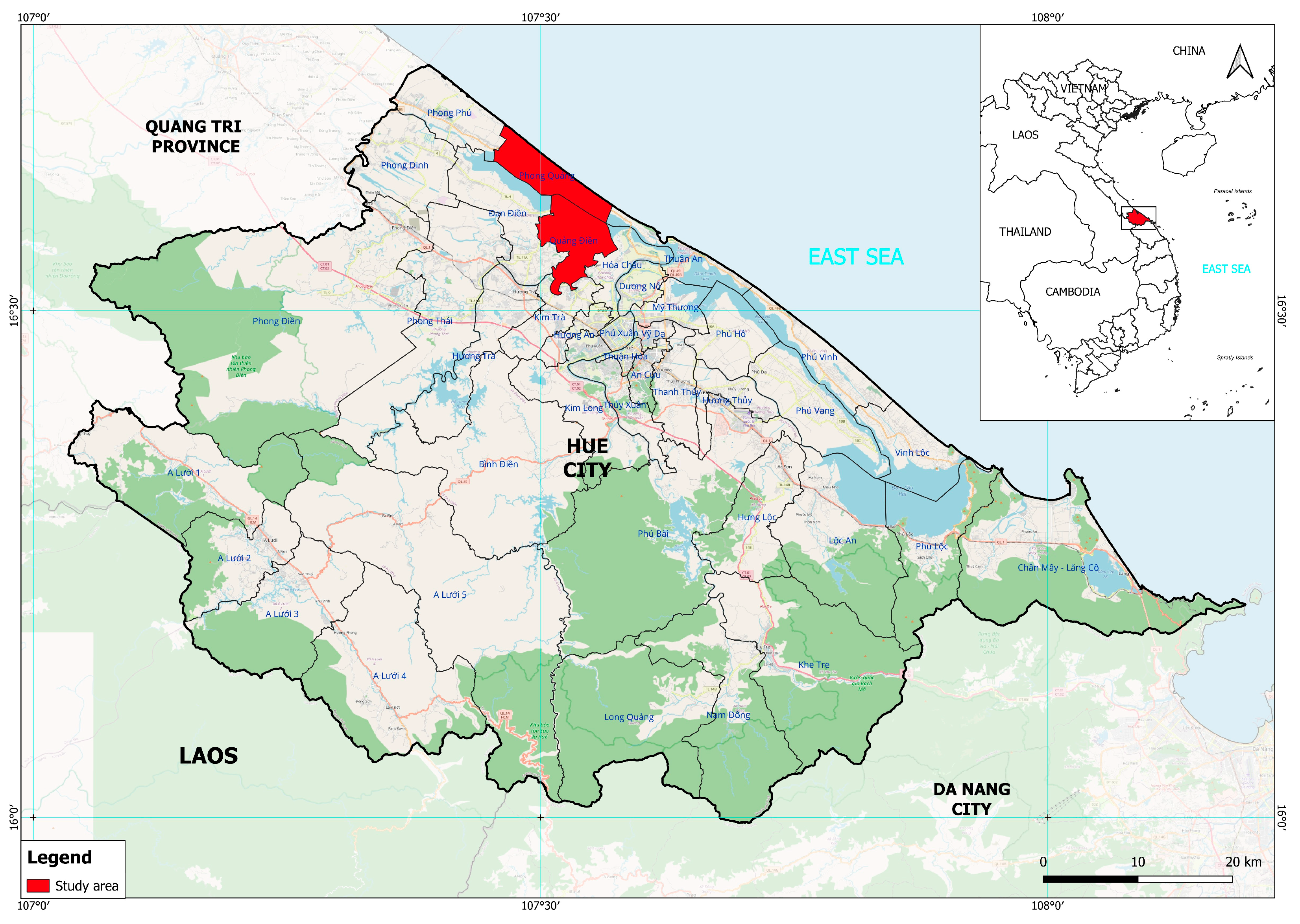

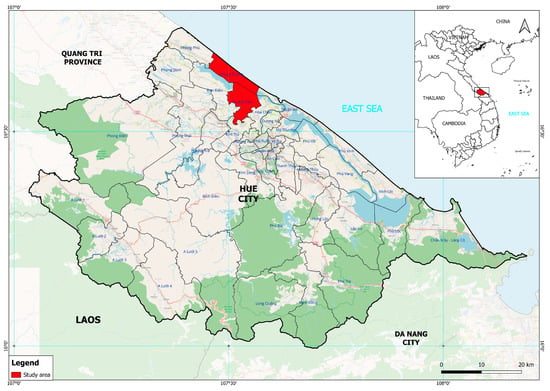

This study was conducted in Phong Quang ward and Quang Dien commune, located in Hue City, Vietnam (Figure 2). According to Resolution No. 1675/NQ-UBTVQH15 dated 16 June 2025, issued by the Standing Committee of the National Assembly, Phong Quang ward was formed through the merger of the entire natural area and population of Phong Hai ward, Quang Cong commune, and Quang Ngan commune. Accordingly, Phong Quang covers an area of 41.70 km2 and has a population of 25,728, reaching 57.17% of the regulatory threshold [39]. This area is considered one of Hue City’s most distinctive communes, bordered by the sea to the east and the Tam Giang–Cau Hai Lagoon to the west, creating an oasis-like terrain. While the area benefits from rich fisheries resources, it is also highly vulnerable to climate hazards such as storms and floods—factors that shape its development trajectory. Similarly, Quang Dien commune was established by merging the entire natural area and population of Sia Town and the communes of Quang Phuoc, Quang An, and Quang Tho. Quang Dien now spans 45.93 km2 and has a population of 41,798 [39]. Agriculture and aquaculture remain the primary livelihoods, although some residents have transitioned to tourism in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. At present, tourism is increasingly recognized as a key economic sector in the commune.

Figure 2.

Map of Phong Quang ward and Quang Dien commune, Hue city, Vietnam.

Site selection was informed by consultations with local experts from the Department of Natural Resources and Environment, as well as with commune-level officials in charge of agriculture, fisheries, labor, and land management. Three main criteria guided the selection of these communes. First, both play an important role in the National Target Program on New Rural Development, which has substantially reshaped rural areas—particularly through changes in land use and the promotion of local economic development using existing labor resources, with an emphasis on youth engagement [40]. Second, the communes possess distinctive geographical and ecological features, including a long coastline, the Tam Giang–Cau Hai Lagoon for aquaculture, and agricultural land [41,42]. This diversity of land use creates a complex socio-ecological system highly relevant to this study. Third, both areas have experienced increasing outmigration of young people to urban centers, alongside rapid industrialization [41,42]. These trends have altered land use practices, livelihood strategies, and employment patterns among rural youth. Together, the two communes reflect the dynamics of evolving rural regions and offer insights that may be applicable beyond the Hue context.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study was conducted over a one-year period, beginning in April 2024, and was carried out in three main phases. In the first phase, a series of pilot visits were undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of the socio-economic and cultural context of the study area through qualitative interviews with key respondents. Specifically, six in-depth interviews were conducted with knowledgeable local individuals using an unstructured questionnaire. This group included a commune official, two village heads, a representative from the women’s union, and two young individuals (one male and one female), all of whom were born and raised in the communes. The interviews focused on issues related to young people’s access to and use of land, existing challenges, and potential support from local authorities and mass organizations. While the primary focus of this study was on youth, engaging local experts provided a broader perspective on the local context and the socio-economic and cultural factors influencing land access. Additionally, this phase facilitated the collection of secondary data.

In the second phase, this study conducted a cross-sectional household survey, with 102 respondents selected from each commune using a semi-structured questionnaire. This study employed a cluster random sampling method, incorporating gender disaggregation techniques to ensure the inclusion of voices from disadvantaged groups. Based on the youth population lists provided by each commune, the research team stratified participants by gender (male and female) and educational status (in-school and out-of-school) prior to conducting randomized interviews within each subgroup. In total, 204 questionnaires were collected from each commune. However, four questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete data. Ultimately, 200 valid responses per commune were cleaned, coded in Excel, and subsequently analyzed using SPSS Statistics 20 software. To analyze the factors influencing rural youth migration, a logistic regression model was employed, with the dependent variable represented as a binary outcome: 0 for non-migration and 1 for migration. Logistic regression is a widely used tool in social science research for modeling binary outcomes, such as youth migration decisions in rural areas [43]. Stokes et al. (2012) note its suitability for analyzing survey data with categorical variables, allowing researchers to assess how factors like education, gender, and land tenure influence migration behavior [44]. Long and Freese (2014) further highlight its value in sociological studies for testing theoretical models of decision making, as it provides clear and interpretable results through odds ratios and predicted probabilities [45]. These perspectives underscore its importance in generating evidence-based insights into rural youth migration. Furthermore, three focus group discussions (FGDs) were organized, each consisting of three to four young participants, including both men and women. During these discussions, three Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) tools were employed to gather relevant data. First, the village mapping method was used to identify different land use areas within the study site. Second, the paired comparison method was applied to determine young people’s priorities regarding land access. Lastly, a SWOT analysis was conducted to assess the community’s needs and challenges in accessing land. The final phase involved follow-up visits and field observations to supplement and validate qualitative data collected in the earlier stages. These visits provided additional contextual insights and ensured a comprehensive understanding of the issues under investigation.

3. Results

3.1. Youth Perceptions of Land Access, Tenure Security, and Economic Aspirations

The findings of the survey offer critical insights into rural youth perceptions of land access, tenure security, and future economic prospects in Central Vietnam. Out of 200 respondents, a majority (56%, n = 112) reported having access to land, with most acquiring it through inheritance. The average size of agricultural landholdings was approximately 892.8 m2 (Table 2). However, formal ownership and documentation remain limited. Only 17% of respondents reported having their names on residential Land Use Certificates (LUCs), and just 3% (n = 6) held official ownership of agricultural land. Additionally, 24.2% were uncertain about the legal validity of their land documents, and 38.5% expressed concerns about the security of their land tenure.

Table 2.

Summary of rural youth perceptions on land access, tenure security, and economic aspirations.

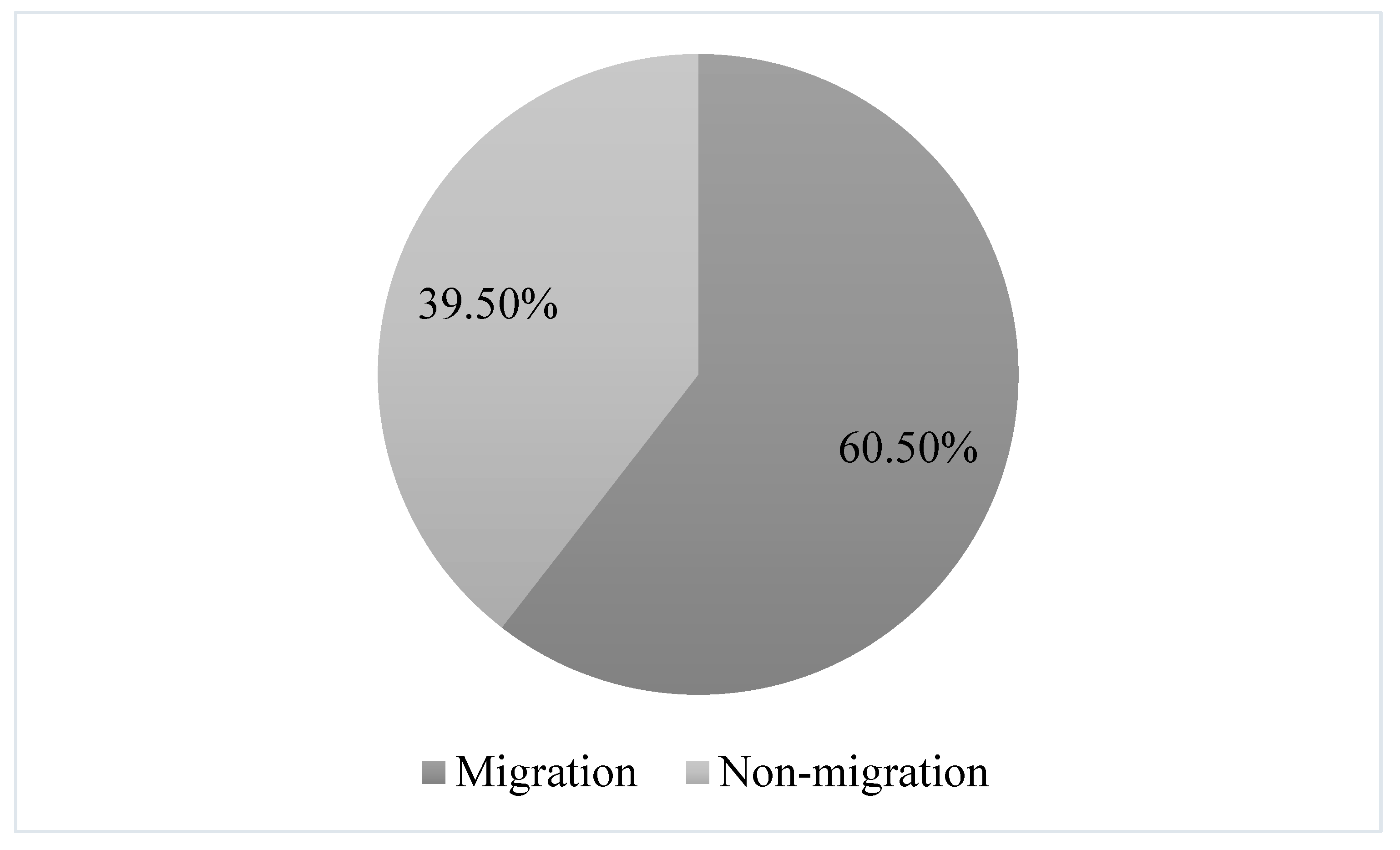

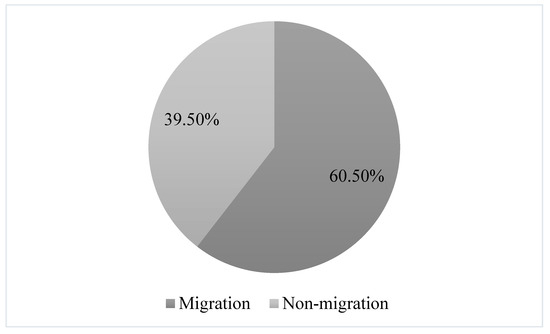

Despite a relatively high level of trust in the prospect of land inheritance (mean score = 3.71 on a 5-point Likert scale), a significant portion of respondents perceived their current land situation as insecure. This suggests a gap between expectations of future ownership and present legal or administrative recognition of tenure. Land access emerged as a pivotal factor in shaping youth aspirations. The importance of land for future livelihood planning was rated highly, with a mean score of 4.2 on a 5-point scale. Notably, 39.5% of respondents indicated a desire to migrate outside their locality in search of employment opportunities—an inclination especially prevalent among those without land or with insecure tenure (Figure 3). This relationship was further emphasized during focus group discussions. A 22-year-old male participant shared:

“Even if I want to stay, I have no land to farm. My parents said the land is too small, and I should look for work in the city instead”

Figure 3.

Proportion of respondents expressing intent to migrate for work.

This quote underscores the influence of land constraints and tenure insecurity on the migration choices of rural youth. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics also played a significant role in shaping migration tendencies (see Table 3). Among the 121 respondents who expressed a desire to migrate in the future, 52 were women and 69 were men. The findings indicate that younger individuals (average age group = 1.47) and those from economically disadvantaged households were more likely to consider migration. The average education level was 2.98, suggesting that most had completed secondary or high school, with limited access to higher education possibly influencing their migration intentions.

Table 3.

Household demographics and socio-economic characteristics (N = 200).

Economic vulnerability emerged as a key driver. A majority of respondents (76%) belonged to low- to middle-income households (mean income level = 1.76). Financial pressures were compounded by household size, with 69% (n = 138) of respondents living in families with more than three members (mean = 1.69). Larger household sizes may intensify competition for limited resources, thereby increasing the likelihood of youth migration. Remittances also played a notable role in shaping economic expectations and household dynamics. Several families received regular financial support from relatives abroad, particularly from the United States. As one respondent explained:

“My family has three members working in the nail industry in the U.S., and they send us about 150 to 200 USD each month to help with living expenses. We consider this a form of permanent salary.”

This perception of remittances as a stable income source may encourage migration among youth who view overseas employment as a viable economic strategy. Lastly, household power dynamics revealed moderate levels of youth decision-making autonomy, with a mean score of 2.84. This indicates that many respondents perceive limited agency in shaping household or land-related decisions, which may further motivate them to seek independence and livelihood opportunities elsewhere. Overall, the findings suggest that land tenure insecurity—combined with demographic pressures, limited educational and economic opportunities, and constrained agency—significantly contributes to rural youth migration intentions in Central Vietnam.

3.2. Factors Affecting Migration Decision Among Rural Vietnamese Youth

The logistic regression model used to analyze factors affecting migration and employment decisions among rural Vietnamese youth demonstrates strong statistical validity. The Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients (χ2 = 77.233, df = 12, p = 0.000) confirms that the model significantly improves upon the null model, indicating that at least some independent variables contribute meaningfully to predicting migration and employment choices. The model’s goodness-of-fit is supported by the Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (χ2 = 5.420, df = 8, p = 0.712), suggesting no significant difference between observed and predicted classifications, thereby validating the model’s fit to the data. The model’s classification accuracy improved from 60.5% (baseline model) to 78.0% (full model), with correct classification rates of 84.3% for migration cases and 68.4% for non-migration cases (Table 3). Additionally, the Cox and Snell R2 (0.304) and Nagelkerke R2 (0.412) indicate that the model explains approximately 30.4% to 41.2% of the variance in migration and employment decisions, suggesting a moderate level of explanatory power (Table 4). These results indicate that the model effectively captures key determinants of migration and employment decisions, though the lower classification accuracy for non-migration cases suggests potential areas for refinement.

Table 4.

Correct classification rates.

The logistic regression analysis is presented in Table 5. Six variables were found to significantly influence youth migration decisions (p < 0.05). Among these, three factors with Exp(B) > 1 including gender (p = 0.025, Exp(B) = 2.335), education level (p = 0.000, Exp(B) = 3.019), and income group (p = 0.030, Exp(B) = 2.084), were associated with a higher likelihood of migration. This suggests that males, individuals with higher education, and those from more financially stable households are more inclined to migrate. In contrast, land-related variables were strongly associated with reduced migration tendencies. Youth whose names are registered on agricultural land were significantly less likely to migrate (p = 0.021, Exp(B) = 0.042), underscoring the stabilizing effect of land ownership. Similarly, having trust in inherited land reduced migration likelihood (p = 0.003, Exp(B) = 0.510), as it provides a sense of long-term security. On the other hand, concern about land security increased the probability of migration (p = 0.000, Exp(B) = 0.223), highlighting land tenure insecurity as a key push factor. These findings align with existing literature, demonstrating that education and economic aspirations drive migration, while land ownership and inheritance security anchor youth in rural areas. Interestingly, variables such as age, family size, and total land area owned do not show statistically significant effects, challenging some common assumptions about migration determinants.

Table 5.

The results of the logistic regression model.

4. Discussion and Policy Implications

This study sheds light on the complex interplay between land access, tenure security, and migration decisions among rural youth in Central Vietnam, drawing on two case studies from Hue city. The findings reveal a nuanced landscape in which land ownership, legal recognition, and perceptions of security significantly shape young people’s livelihood choices and mobility. These results contribute to a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of land-related factors in rural transformation and migration patterns, both within Vietnam and in broader global contexts.

Consistent with previous studies [21,29,32,37,46], gender, education level, and income significantly influenced migration intentions. Male respondents were more likely to migrate, reflecting entrenched gender norms and unequal labor market opportunities that continue to limit female mobility. This finding aligns with Cam et al. (2013), who highlighted that women remain disadvantaged in land access due to the patriarchal nature of inheritance systems [46]. Other studies further emphasize that young women often face unique constraints, including discriminatory inheritance practices, lack of formal land titles, and limited bargaining power within households [47]. These structural inequalities not only reduce women’s access to productive resources but also shape their migration decisions. While some young men may migrate in search of better opportunities, many young women may feel compelled to remain due to family expectations, caregiving roles, or fear of social stigma. Moreover, in Vietnam, land inheritance is still governed largely by customary norms, often privileging eldest sons or male heirs. These intergenerational arrangements can result in exclusion and disempowerment for daughters and younger siblings, exacerbating perceptions of tenure insecurity [48]. We support Alhola and Gwaindepi’s conclusion that greater opportunities for women can be realized if customary land systems are restructured to better secure women’s land rights [21]. Therefore, promoting gender-equitable land governance is essential—not only to empower rural women economically, but also to expand their choices regarding mobility. Policymakers should prioritize legal reforms that recognize women’s equal rights to own, inherit, and manage land, while also addressing the social norms and institutional barriers that restrict their participation in land-related decision making. Gender-sensitive land policies can ultimately influence migration trends by enabling young women to make autonomous livelihood choices, whether through staying, diversifying locally, or migrating on their own terms.

Likewise, the significance of education and income in predicting migration decisions aligns with broader migration theory. Youth with higher education levels and greater financial means often have both the aspiration and the capacity to migrate. In this study, higher education attainment and middle-income status were associated with increased migration intent. This supports the argument that migration is not merely a response to deprivation, but also a proactive strategy employed by relatively better-off youth to pursue broader opportunities, often in urban or international labor markets. These results are consistent with human capital theory [49], which posits that individuals with greater skills and resources are more likely to migrate to maximize their returns. They also reflect the dynamics described in the push–pull framework, where land tenure insecurity operates as a key push factor, while urban economic opportunities serve as strong pull factors. The observed pattern reinforces the idea that migration is increasingly a strategic choice for upward mobility, not simply a last resort [50,51]. National trends in Vietnam confirm this trajectory: according to the 2019 Population and Housing Census, 61.8% of migrants are aged 20–39, indicating a predominance of youth in internal migration flows [52]. However, while education increases aspirations, rural areas often lack the economic and professional opportunities needed to fulfill these expectations, thus accelerating out-migration. Addressing this challenge requires targeted policy interventions. Investments in rural vocational training centers aligned with local labor market demands can provide youth with practical, non-farm skills. Agricultural entrepreneurship programs and start-up grants can empower educated youth to innovate and create value-added agricultural enterprises [53]. In addition, supporting youth cooperatives and digital platforms for accessing markets can offer collective economic opportunities, enabling rural youth to remain locally engaged while staying competitive [47]. These interventions are essential to bridging the gap between rising aspirations and limited rural opportunities—ultimately reducing migration pressures and fostering sustainable rural development.

More importantly, land tenure security emerged as a critical factor in discouraging migration. the analysis indicates that individuals whose names were officially listed on agricultural land were significantly less likely to express migration plans, underscoring the anchoring effect of formal land ownership in rural communities. However, only 56% of surveyed youth reported owning land, mostly through inheritance, and a mere 3% had their names formally registered on agricultural land titles. This is in line with previous research, which shows that rural youth increasingly view migration as a strategy for upward mobility, a channel of investment, and economic diversification [54,55,56]. Deininger and Jin demonstrated that secure tenure promotes investment and long-term planning in rural China, thus reducing the incentive to migrate [29]. Similarly, In Nigeria, secure land tenure improved youth willingness to invest in agriculture rather than migrate [57]. In addition to formal titles, the perception of secure land inheritance was also negatively associated with migration intentions. Youth who trusted they would inherit land showed reduced likelihood of migrating, which emphasizes the importance of intergenerational land transfer in sustaining rural livelihoods. Nearly 40% of youth in this study expressed a preference to migrate for work, with higher rates among landless individuals. Globally, similar trends are evident in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, where youth struggle to access productive land due to inheritance patterns, land market failures, and legal barriers [58]. While access to land can serve as a stabilizing asset, its absence—especially when coupled with limited employment opportunities—pushes youth toward urban labor markets. This evidence aligns with the environmental economics literature emphasizing that secure land tenure fosters sustainable rural development. Formal land registration reduces uncertainty and promotes long-term investments in agriculture and environmental stewardship [59]. Similarly, when youth perceive their inheritance as secure, they are more likely to remain in their communities and engage in agricultural or locally embedded economic activities. This sense of socio-environmental rootedness strengthens place attachment and reduces the appeal of migration as a livelihood strategy. Conversely, tenure insecurity—whether due to lack of formal documentation or perceived vulnerability—can erode confidence in the viability of land-based livelihoods. In such contexts, young people are more likely to migrate, not only in search of better economic opportunities but also due to the perceived instability of staying. This dynamic may also contribute to the abandonment of environmentally sustainable land management practices, as insecure tenure discourages long-term in-vestment [60].

We argue that secure land access is not only essential for sustaining rural livelihoods but also serves as a cornerstone for youth engagement, socio-economic stability, and long-term rural resilience. From this perspective, several key implications emerge at the intersection of land security and migration. First, land tenure security must be prioritized in rural development policies. The strong inverse relationship between formal land ownership and migration intentions highlights the stabilizing effect of secure land rights. Youth with land titles or confidence in inheritance are more likely to stay, invest in farming, and pursue long-term strategies. Strengthening land registration systems, accelerating LURCs issuance, and ensuring youth—especially women and younger siblings—are included in land documentation can help anchor future generations in rural areas [48]. Global models like Rwanda’s Land Tenure Regularization Program and Ethiopia’s Second-Level Land Certification have shown that secure rights promote agricultural investment and environmental stewardship [58,61]. In Vietnam, land reforms under the 2024 Land Law should be paired with legal literacy, gender-sensitive services, and infrastructure support to ensure formal rights translate into actual empowerment. Secure land access also underpins environmental efforts such as agroforestry, reforestation, and climate-adaptive agriculture [26].

Second, sustainable rural development must go beyond agriculture and offer diversified economic opportunities. While land access is important, many youths migrate in search of education, employment, and entrepreneurship. Expanding rural industries, agribusiness, and eco-tourism can generate jobs and reduce out-migration [62]. Policy measures should include tax incentives for rural business investment, microfinance, startup support, and vocational training tailored to local market demands [63]. Improving access to modern farming technologies and market integration can also revitalize agriculture for youth. Targeted financial support and business training can help young people establish local enterprises, turning migration into a choice—not a necessity [52]. Third, structural inequalities that constrain the migration choices of disadvantaged youth must be addressed. Those with low income, insecure land rights, or limited education often migrate under pressure rather than choice. Equitable access to land, credit, and education is essential for empowering youth as agents of change [11,64]. Higher education often leads to greater migration intentions due to a rural–urban mismatch in job opportunities. To counter this, Vietnam should invest in vocational training for green jobs, digital entrepreneurship, and climate-resilient farming—aligned with the National Strategy on Green Growth (2021–2030) and the New Rural Development Program (2021–2025). Innovation hubs, scholarships, and improved internet infrastructure can connect rural youth to meaningful work, including remote and digital employment. Finally, youth inclusion should be a core pillar of Vietnam’s rural development strategy. Despite progress in agriculture and infrastructure, youth-specific needs in land access, employment, and participation remain overlooked. Local governments should embed youth voices in decision making through youth councils, participatory planning, and dedicated funding for youth-led initiatives [47,65]. These measures will ensure rural development is not only modernized but also inclusive and sustainable.

5. Conclusions

The growing youth population in rural Vietnam presents both promise and challenge in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality), by showing that secure land tenure reduces youth migration and supports rural livelihoods, especially for women. It also supports SDG 8 (Decent Work) through its call for vocational training and rural entrepreneurship, and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by highlighting how education, income, and gender influence migration decisions. While youth hold significant potential as agents of change, they often face persistent barriers to stable employment and secure land tenure-key pillars of sustainable livelihoods. This study explored how demographic and land-related factors influence migration and employment decisions among rural Vietnamese youth through a mixed-methods approach involving interviews and focus group discussions. Findings reveal that gender, higher education and income levels increase the likelihood of migration, supporting the view that mobility is often a strategic, resource-enabled decision rather than merely a response to hardship. At the same time, land-related factors, such as formal land registration, trust in inherited land, and perceived tenure security, reduce the tendency to migrate by fostering long-term stability and community attachment. These results point to the need for integrated rural development policies that both expand educational and employment opportunities and strengthen land tenure systems. Equitable access to quality education and vocational training can empower youth locally or prepare them for opportunities elsewhere. Meanwhile, improving land tenure security through transparent registration, inheritance protections, and legal clarity can address a major push factor behind rural out-migration. This study highlighted the dual importance of economic capacity and land security in shaping youth mobility. Empowering young people with real choices—grounded in opportunity rather than driven by insecurity—is essential for sustainable, inclusive rural development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.T.N., T.T.P. and N.H.N.; methodology, N.T.N., T.T.P. and N.H.N.; software, N.T.N.; validation, N.T.N.; formal analysis, N.T.N.; investigation, N.T.N.; resources, N.T.N.; data curation, N.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T.N., T.T.P. and N.H.N.; writing—review and editing, N.T.N., T.T.P. and N.H.N.; visualization, N.T.N.; supervision, T.T.P. and N.H.N.; project administration, N.T.N., T.T.P. and N.H.N.; funding acquisition, N.H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by Hue University under the Core Research Program, Grant No. NCTB. DHH.2024.05.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to current Vietnamese regulations and our university’s institutional policy, formal ethics approval is not required for this type of research. The study employed non-clinical, low-risk social science menthods, specifically household serveys focusing on land access. It did not involve the collection of sentitive personal data or medical informaiton. The research adhered to standard ethical practices in the social sceince. Participation was entirely voluntary, and informaed oral consent wast obtained form all paticipants prior to the interviews. The study did not involve any form of physical or psychological intervention, nor did it invlude vulnerable populations as defined by law. Therefore, this study is considered exempt form ethics committee review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to the People’s Committee of Quang Cong Commune (now is Phong Quang ward) and the People’s Committee of Quang Tho Commune (now is Quang Dien commune) for their valuable assistance throughout the research process. Special appreciation is given to the local respondents for providing information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shipton, P. Land and culture in tropical Africa: Soils, symbols, and the metaphysics of the mundane. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1994, 23, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, L.T. Vietnam’s Agriculture: Some Achievements in the Period 2010–2022, Orientation and Solutions for Development in the Coming Time. Economic and Forecast Magazine, No. 28, October 2023. 2023. Available online: https://kinhtevadubao.vn/nong-nghiep-viet-nam-mot-so-ket-qua-dat-duoc-trong-giai-doan-2010-2022-dinh-huong-va-giai-phap-phat-trien-thoi-gian-toi-28546.html (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- GOV. Opening Speech of the 5th Central Conference, 13th Tenure by General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong. 2022. Available online: https://baochinhphu.vn (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Moreda, T. The social dynamics of access to land, livelihoods and the rural youth in an era of rapid rural change: Evidence from Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosec, K.; Ghebru, H.; Holtemeyer, B.; Mueller, V.; Schmidt, E. The Effect of Land Access on Youth Employment and Migration Decisions: Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S.; Chamberlin, J.; Headey, D.D. Land pressures, the evolution of farming systems, and development strategies in Africa: A synthesis. Food Policy 2014, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D. On the Word “Access”. 2020. Available online: https://transportist.org/2020/07/18/on-the-word-access/ (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Marx, K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (3vols); Charles H. Kerr and Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs. Inter-Agency Commission; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Feder, G. Land institutions and land markets. Handb. Agric. Econ. 2001, 1, 287–331. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia; (No. 58); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of Vietnam; National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013.

- The 2024 Land Law; Law No. 31/2024/QH15; National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024.

- Tan, C. Agricultural Land is Increasingly Depleted. 2024. Available online: https://nhandan.vn/dat-nong-nghiep-ngay-cang-suy-kiet-post814273.html (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Open Development Mekong. Summary Report: Land Concentration for the Poor in Vietnam. 2018. Available online: https://data.vietnam.opendevelopmentmekong.net/vi/dataset/bao-cao-tom-t-t-t-p-trung-d-t-dai-cho-ngu-i-ngheo-vi-t-nam (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Huong, H. Removing Barriers to Agricultural Land Use, Enabling Agricultural Products to Participate in Global Value Chains. 2023. Available online: https://quochoi.vn/UserControls/Publishing/News/BinhLuan/pFormPrint.aspx?UrlListProcess=/content/tintuc/lists/news&ItemID=77098 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Hung, G. Rapidly Shrinking Agricultural Land, Pressure on Sustainable Agricultural Production. 2024. Available online: https://nongnghiepmoitruong.vn/dat-nong-nghiep-thu-hep-nhanh-ap-luc-len-san-xuat-nong-nghiep-ben-vung-d393658.html (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Vnexpress. The Youth Rate Drops Sharply Due to the Aging Population. 2023. Available online: http://kinhtetrunguong.vn/web/guest/xa-hoi/ty-le-thanh-nien-giam-manh-vi-gia-hoa-dan-so.html (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Ly, N.T.T.; Kiet, H.; Ngu, N.H. Current situation of land access by households and individuals in Cao Lanh City, Dong Thap Province [thực trạng tiếp cận đất đai của hộ gia đình, cá nhân tại thành phố Cao Lãnh, tỉnh Đồng Tháp]. Hue Univ. J. Sci. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 128, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Alhola, S.; Gwaindepi, A. Land tenure formalisation and perceived tenure security: Two decades of the land administration project in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2024, 143, 107195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaiaupuni, S.M. Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Soc. Forces 2000, 78, 1311–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyanga, M.; Jayne, T. Effects of rising rural population density on smallholder agriculture in Kenya. Food Policy 2014, 48, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Exploring the “implementation gap” in land registration: How it happens that Ghana’s official registry contains mainly leaseholds. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.D.; Tan, N.Q.; Thang, T.N.; Que, H.T.H.; Van Tuyen, T. Towards Inclusive Resilience: Understanding the Intersectionality of Gender, Ethnicity, and Livelihoods in Climate-prone Upland Areas of Central Vietnam. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2023, 11, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, T.T.; Tan, N.Q.; Dinh, N.C.; Huong, T.Q.; Nhat, N.T.; Ngu, N.H. Reinforcing adaptation: How climate change perceptions and land tenure security shape ethnic minority resilience in Vietnam. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezu, S.; Barrett, C. Employment dynamics in the rural nonfarm sector in Ethiopia: Do people experiencing poverty have time on their side? J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 1223–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanWey, L.K. Land Ownership as a Determinant of International and Internal Migration in Mexico and Internal Migration in Thailand. Int. Migr. Rev. 2005, 39, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S. Tenure security and land-related investment: Evidence from Ethiopia. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2006, 50, 1245–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Kelly, P.M.; Winkels, A.; Huy, L.Q.; Locke, C. Migration, remittances, livelihood trajectories, and social resilience. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanWey, L.K. Land ownership as a determinant of temporary migration in Nang Rong, Thailand. Eur. J. Popul. 2003, 19, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, J. Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2002, 28, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, D.; Rapoport, H. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: Theory and evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 84, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemi, D. Economic Behavior of Albanian Immigrants during the Economic Crisis in Greece. In Proceedings of the TMC2017 Conference Proceedings, Athens, Greece, 23–26 August 2017; Transnational Press London: London, UK, 2017; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S.; Ravallion, M.; van de Walle, D. Intergenerational mobility and interpersonal inequality in an African economy. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramitzky, R.; Boustan, L.P.; Eriksson, K. Have the poor always been less likely to migrate? Evidence from inheritance practices during the age of mass migration. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 102, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Leaving the countryside: Rural-to-urban migration decisions in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A.; Mueller, V. Do limitations in land rights transferability influence mobility rates in Ethiopia? J. Afr. Econ. 2012, 21, 548–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Standing Committee of the National Assembly. Resolution No. 1675/NQ-UBTVQH15 Dated June 16, 2025 on Arrangement of Communal Administrative Units of Hue City in 2025; National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2025.

- Government of Vietnam. Decision No. 263/QD-TTg of the Prime Minister: Approving the National Target Program on New Rural Development for the 2021-2025 Period; Government of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022.

- Quang Cong Commune People’s Committee. Socio-Economic Report for 2022, 2023, and 2024; Quang Cong Commune People’s Committee: Hue City, Vietnam, 2025.

- Quang Tho Commune People’s Committee. Socio-Economic Report for 2022, 2023, and 2024; Quang Tho Commune People’s Committee: Hue City, Vietnam, 2025.

- Allison, P.D. Logistic Regression Using SAS: Theory and Application; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, M.E.; Davis, C.S.; Koch, G.G. Categorical Data Analysis Using SAS; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2006; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cam, H.; Sang, L.T.; Cham, N.T.P.; Lan, N.T.P.; Tran, N.T.; Long, V.T. The Women’s Access to Land in Contemporary Vietnam; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, N.C.; Tan, N.Q.; Ty, P.H.; Phuong, T.T.; Linh, N.H.K. Bridging climate vulnerability and household poverty: Perspectives from coastal fishery communities in Vietnam. Local Environ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkvliet, B.J.T. An Approach for Analysing State-Society Relations in Vietnam. J. Soc. Issues Southeast Asia 2001, 16, 238–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S. A theory of migration. Demography 1966, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A.; Harigaya, T. Seasonal migration and improving living standards in Vietnam. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 89, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Unequal access to land and the current migration crisis. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Statistics Office and UNFPA. Factsheet. Urbanization and Migration in Vietnam. 2019. Available online: https://vietnam.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/migration_and_urbanization_factsheet_vie.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Phuong, L.T.H.; Wals, A.; Sen, L.T.H.; Hoa, N.Q.; Van Lu, P.; Biesbroek, R. Using a social learning configuration to increase Vietnamese smallholder farmers’ adaptive capacity to respond to climate change. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.; Le, S.T.; Mao, N.H.; Chau, K.M.; Condon, J.; Kristiansen, P. Rural Youth Aspirations in the Face of Environmental, Economic and Social Pressures: Transformation in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2025, 37, 524–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Raabe, K.; Grote, U. Rural–urban migration, household vulnerability, and welfare in Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 71, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenke, G.; Brines, S.; Hernandez, N.; Li, K.; Glancy, R.; Cabrera, J.; Neal, B.H.; Adkins, K.A.; Schroeder, R.; Perfecto, I. Farmer Perceptions of Land Cover Classification of UAS Imagery of Coffee Agroecosystems in Puerto Rico. Geographies 2024, 4, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebru, H.; Amare, M.; Mavrotas, G.; Ogunniyi, A. Role of Land Access in Youth Migration and Employment Decisions: Empirical Evidence from Rural Nigeria; Working Paper 58; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S.T.; Ghebru, H. Land tenure reforms, tenure security and food security in poor agrarian economies: Causal linkages and research gaps. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 10, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resurreccion, B.P.; Van Khanh, H.T. Able to come and go: Reproducing gender in female rural-urban migration in the Red River Delta. Popul. Space Place 2007, 13, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Geest, K. North-South migration in Ghana: What is its role for the environment? Int. Migr. 2011, 49, e69–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.A.; Deininger, K.; Goldstein, M. Environmental and gender impacts of land tenure regularization in Africa: Pilot evidence from Rwanda. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N.Q.; Ubukata, F.; Dinh, N.C.; Ha, V.H. Rethinking community-based tourism initiatives through community development lens: A case study in Vietnam. Community Dev. 2024, 55, 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakre, O.; Dorasamy, N. Driving urban-rural migration through investment in water resource management in subsistence farming: The case of Machibini. Environ. Econ. 2017, 8, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Florkowski, W.J.; Liu, Z. Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter? Land 2025, 14, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Espíndola, R.; Lalama-Noboa, E.; Cuyo-Cuyo, J. Toward Sustainable Urban Drainage Planning? Geospatial Assessment of Urban Vegetation Density under Socioeconomic Factors for Quito, Ecuador. Geographies 2022, 2, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).