Quantifying Who Will Be Affected by Shifting Climate Zones

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets Used

2.2. Analyses Conducted

3. Results

3.1. Projected Climate Zone Shifts

3.2. Projected Population Exposure to Climate Zone Shifts

4. Discussion

4.1. Repartitioning Land Area and People between Climate Zones

4.2. Exposure to Shifting Climate Zones Compared with Other Exposure Metrics

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions for Study

5. Conclusions

- Changing climate zones will affect a large amount of the land surface and global population. By the end of this century, 9% to 15% of the land surface could shift its climate zone classification. These shifts will occur in areas that are home to 1.3 billion to 1.6 billion people (14% to 21% of the global population).

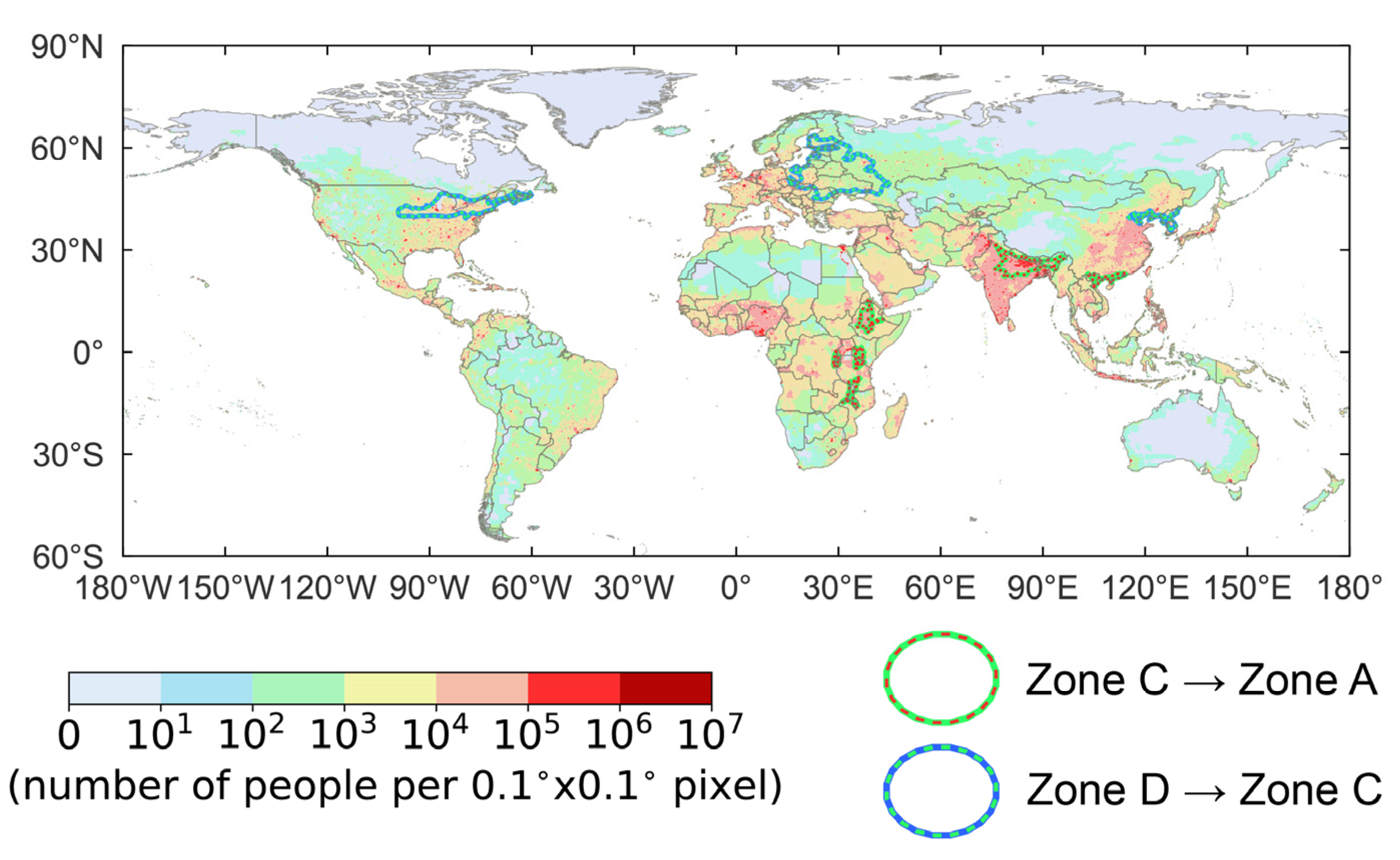

- The largest population exposure occurs in densely populated temperate regions projected to be classified as tropical in the future. These regions include parts of northern India, South Asia, and the East African Rift Valley. A secondary hotspot occurs for populated boreal regions projected to be classified as temperate in the future. These regions include parts of the northern United States, Eastern Europe, northern China, and the Korean Peninsula.

- Hotspots for population exposure to changing climate zones are geographically different from the hot spots for other metrics of climate change exposure. Thus, this study identifies new populations that may experience adverse impacts from climate change. It expands the number of people impacted by climate change beyond those identified by existing exposure metrics and those facing Earth System changes such as sea-level rise and permafrost loss.

- Earth’s land surface will shift toward warmer (i.e., tropical) and drier (i.e., arid) climates. The global population will also repartition toward hotter and drier climates. This repartitioning is due to differences in the projected population growth between developing and developed countries and shifting climate zones.

- Future research is needed into the impacts societies will face when climate zones shift. This study identifies two types of climate zone shifts that will produce large population exposures. The impacts of these shifts should be the focus of future studies. Moreover, exposure to climate zone shifts may impact future demographic changes through climate migration. Shifting climate zones can help inform the next generation of population projections.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Climate Zone | Mid-Century | Late-Century | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSP2-RCP4.5 | SSP5-RCP8.5 | SSP2-RCP4.5 | SSP5-RCP8.5 | |

| A | 2279 (691) | 1871 (760) | 2546 (832) | 1732 (866) |

| B | 958 (51) | 711 (69) | 1017 (54) | 625 (142) |

| C | 307 (−507) | 223 (−513) | −83 (−632) | −129 (−576) |

| D | −195 (−226) | −251 (−306) | −282 (−244) | −422 (−423) |

| E | −14 (−9) | −18 (−9) | −17 (−9) | −22 (−9) |

References

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartusek, S.; Kornhuber, K.; Ting, M. North American heatwave amplified by climate change-driven nonlinear interactions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeter, K.J.; Harley, G.L.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Cook, E.R.; Coulthard, B.L.; Dye, L.A.; Homfeld, I.K. Unprecedented 21st century heat across the Pacific Northwest of North America. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, R.J. Climate change and ecosystem services. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C.; Morecroft, M.D.; Trisurat, Y.; Adrian, R.; Anshari, G.Z.; Arneth, A.; Gao, Q.; Gonzalez, P.; Harris, R.; Price, J.; et al. Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Services. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 197–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2022: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, F.; Kottek, M. Comments on: “The thermal zones of the earth” by Wladimir Köppen (1884). Meteorol. Z. 2011, 20, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, H.W. Using the Köppen classification to quantify climate variation and change: An example for 1901–2010. Environ. Dev. 2013, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, M. The classification of climates from Pythagoras to Koeppen. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1999, 80, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Liang, S.; Wang, D. Observed and projected changes in global climate zones based on Köppen climate classification. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá Júnior, A.; de Carvalho, L.G.; Da Silva, F.F.; de Carvalho Alves, M. Application of the Köppen classification for climatic zoning in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 108, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, S.; Huang, H.; Deng, Y.; Yang, W. Macro-analysis of climatic factors for COVID-19 pandemic based on Köppen–Geiger climate classification. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 33, 053104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, M.R.; Parhi, P.; Gentine, P.; Tatonetti, N.P. Climate classification is an important factor in assessing quality-of-care across hospitals. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friess, W.A.; Rakhshan, K.; Davis, M.P. A global survey of adverse energetic effects of increased wall insulation in office buildings: Degree day and climate zone indicators. Energy Effic. 2017, 10, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Wu, Q. Significant anthropogenic-induced changes of climate classes since 1950. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rohli, R.V.; Joyner, T.A.; Reynolds, S.J.; Shaw, C.; Vázquez, J.R. Globally extended Köppen–Geiger climate classification and temporal shifts in terrestrial climatic types. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 3, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubel, F.; Kottek, M. Observed and projected climate shifts 1901-2100 depicted by world maps of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Meteorol. Z. 2010, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanf, F.; Körper, J.; Spangehl, T.; Cubasch, U. Shifts of climate zones in multi-model climate change experiments using the Köppen climate classification. Meteorol. Z. 2012, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalák, P.; Farda, A.; Zahradníček, P.; Trnka, M.; Hlásny, T.; Štěpánek, P. Projected shift of Köppen–Geiger zones in the central Europe: A first insight into the implications for ecosystems and the society. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 3595–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; Kainuma, M.; Riahi, K.; Thomson, A.; Hibbard, K.; Hurtt, G.C.; Kram, T.; Krey, V.; Lamarque, J.F.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Riahi, K.; Ebi, K.L.; Hallegatte, S.; Carter, T.R.; Mathur, R.; Van Vuuren, D.P. A new scenario framework for climate change research: The concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Clim. Chang. 2014, 122, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, B.; Tebaldi, C.; O’Neill, B.C.; Oleson, K.; Gao, J. Avoiding population exposure to heat-related extremes: Demographic change vs climate change. Clim. Chang. 2018, 146, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Li, H. Increased population exposure to precipitation extremes under future warmer climates. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 034048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohat, G.; Flacke, J.; Dosio, A.; Dao, H.; van Maarseveen, M. Projections of human exposure to dangerous heat in African cities under multiple socioeconomic and climate scenarios. Earth’s Future 2019, 7, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swain, D.L.; Wing, O.E.; Bates, P.D.; Done, J.M.; Johnson, K.A.; Cameron, D.R. Increased flood exposure due to climate change and population growth in the United States. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2020EF001778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhou, B.; Han, Z.; Xu, Y. Substantial increase in daytime-nighttime compound heat waves and associated population exposure in China projected by the CMIP6 multimodel ensemble. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Liang, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z. A 1 km global dataset of historical (1979–2013) and future (2020–2100) Köppen–Geiger climate classification and bioclimatic variables. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5087–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Global 1-km Downscaled Population Base Year and Projection Grids Based on the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, Revision 01; NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC): Palisades, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; O’Neill, B.C. Spatially explicit global population scenarios consistent with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Hu, Q.; Huang, W.; Ho, C.H.; Li, R.; Tang, Z. Projected climate regime shift under future global warming from multi-model, multi-scenario CMIP5 simulations. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2014, 112, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, S.; Lutz, W. The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fricko, O.; Havlik, P.; Rogelj, J.; Klimont, Z.; Gusti, M.; Johnson, N.; Kolp, P.; Strubegger, M.; Valin, H.; Amann, M.; et al. The marker quantification of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2: A middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kriegler, E.; Bauer, N.; Popp, A.; Humpenöder, F.; Leimbach, M.; Strefler, J.; Baumstark, L.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Hilaire, J.; Klein, D.; et al. Fossil-fueled development (SSP5): An energy and resource intensive scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, B.; O’Neill, B.C.; McDaniel, L.; McGinnis, S.; Mearns, L.O.; Tebaldi, C. Future population exposure to US heat extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shi, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.A.; Wu, J.; Chen, D. Evolution of future precipitation extremes: Viewpoint of climate change classification. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Xu, C.; Abrams, J.F.; Ghadiali, A.; Loriani, S.; Sakschewski, B.; Zimm, C.; Ebi, K.L.; Dunn, R.R.; Svenning, J.C.; et al. Quantifying the human cost of global warming. Nat. Sustain. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Kohler, T.A.; Lenton, T.M.; Svenning, J.C.; Scheffer, M. Future of the human climate niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11350–11355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, T.; Anderegg, W.R. A vast increase in heat exposure in the 21st century is driven by global warming and urban population growth. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuholske, C.; Caylor, K.; Funk, C.; Verdin, A.; Sweeney, S.; Grace, K.; Peterson, P.; Evans, T. Global urban population exposure to extreme heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024792118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, B.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Zimmermann, J.; Nicholls, R.J. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-a global assessment. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramage, J.; Jungsberg, L.; Wang, S.; Westermann, S.; Lantuit, H.; Heleniak, T. Population living on permafrost in the Arctic. Popul. Environ. 2021, 43, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohli, R.V.; Joyner, T.A.; Reynolds, S.J.; Ballinger, T.J. Overlap of global Köppen–Geiger climates, biomes, and soil orders. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 36, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Historical Period | Mid-Century | Late-Century | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | ||

| A | 21.87 | 23.49 | 24.00 | 23.83 | 24.61 |

| B | 31.26 | 32.03 | 32.61 | 32.25 | 33.54 |

| C | 15.65 | 14.82 | 14.61 | 14.73 | 15.36 |

| D | 24.05 | 24.06 | 23.79 | 24.01 | 22.78 |

| E | 7.17 | 4.90 | 4.29 | 4.49 | 3.02 |

| removed pixels ** | -- | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| added pixels *** | -- | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Climate Zone | Historical Period | Mid-Century | Late-Century | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSP2-RCP4.5 | SSP5-RCP8.5 | SSP2-RCP4.5 | SSP5-RCP8.5 | ||

| A | 28.03 | 42.29 | 41.48 | 45.89 | 43.70 |

| B | 16.14 | 20.58 | 19.62 | 21.57 | 20.42 |

| C | 44.21 | 31.74 | 33.71 | 28.05 | 32.47 |

| D | 10.68 | 4.80 | 4.60 | 3.94 | 2.86 |

| E | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Unaccounted * | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malone, A.G.O. Quantifying Who Will Be Affected by Shifting Climate Zones. Geographies 2023, 3, 477-498. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3030025

Malone AGO. Quantifying Who Will Be Affected by Shifting Climate Zones. Geographies. 2023; 3(3):477-498. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3030025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalone, Andrew G. O. 2023. "Quantifying Who Will Be Affected by Shifting Climate Zones" Geographies 3, no. 3: 477-498. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3030025

APA StyleMalone, A. G. O. (2023). Quantifying Who Will Be Affected by Shifting Climate Zones. Geographies, 3(3), 477-498. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3030025