Mountain Graticules: Bridging Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Historicity to Biocultural Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

Historicity of National Parks and Heritage Management

3. Methods and Conceptualization

4. Results

4.1. Montology Palimpsest Framework

4.2. Montology through Main Players

4.3. The Three “L”s of Critical Biogeography: Location, Locale, and Localities

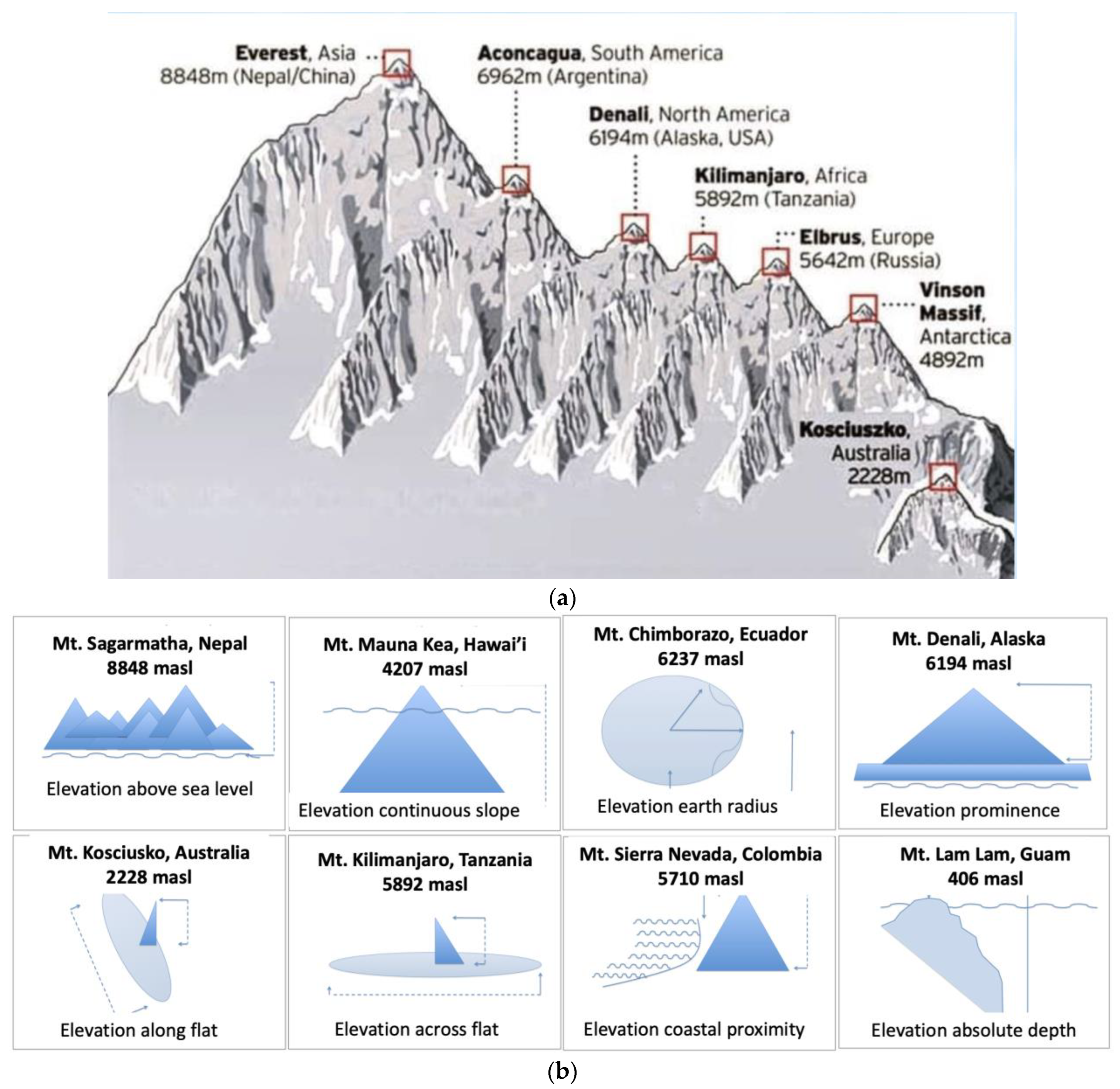

4.3.1. Graticular Sacred Mountains?

4.3.2. The Three “H”s of Biocultural Ethic: Habit, Habitat and Co-inHabitation

4.4. Genderized Mountains Lore

5. Discussion

5.1. Heritagezing Biocultural Mountains

5.2. Heritagization and Heritagized Communities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarmiento, F.O. Montology Manifesto: Echoes towards a transdisciplinary science of mountains. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2512–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Leigh, D.; Porinchu, D.; Woosnam, K.; Gandhi, K.J.K.; King, E.; Pistone, M.; Kavoori, A.; Calabria, J.; Reap, J. (Forthcoming) 4D Global Montology: Towards Convergent and Transdisciplinary Mountain Sciences across time and space. Pirin. J. Mt. Ecol. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, A.; Branca, D. Montología: Una perspectiva de montaña hacia la investigación transdisciplinaria y el desarrollo sustentable. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas 2020, 22, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, O. What is biological cultural heritage and why should we care about it? An example from Swedish rural landscapes and forests. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotherham, I.D. Bio-cultural heritage and biodiversity: Emerging paradigms in conservation and planning. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 3405–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, V.; Exblom, A.; Wästfelt, A. From landscape as heritage to biocultural heritage in a landscape: The ecological and cultural legacy of millennial land-use practices for future natures. In Landscape as Heritage: International Critical Perspectives; Pettenati, G., Ed.; Earthscan-Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. A note to consilience readers. Consilience 2008, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pettenati, G. Why we need a critical perspective on landscape as heritage. In Landscape as Heritage: International Critical Perspectives; Pettenati, G., Ed.; Earthscan-Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, F. A Guide to Decolonize Language in Conservation; Survival International: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.; Hitchner, S. (Eds.) Indigeneity and the Sacred: Indigenous Revival and the Conservation of Sacred Natural Sites in the Americas; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Ibarra, J.T.; Barreau, A.; Pizarro, J.C.; Rozzi, R.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Frolich, L.M. Applied montology using critical biogeography in the Andes. In Mountains: Physical, Human-Environmental, and Sociocultural Dynamics; Fondstan, M.A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Viteri, X.O. Discursive Heritage: Sustaining Andean Cultural Landscapes Amidst Environmental Change. In Conserving Cultural Landscapes: Challenges and New Directions; Taylor, K., St Clair, A., Mitchell, N.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pipan, P.; Topole, M. Heritagization between nature and culture: Managing the Seçovlje salt pans in Slovenia. In Landscape as Heritage: International Critical Perspectives; Pettenati, G., Ed.; Earthscan-Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, K. Presence in affective heritagescapes: Connecting theory to practice. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.M.; Davidson-Hunt, I. Ethnoecology and landscapes. Ethnobiology 2011, 1, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.O. Montology Palimpsest: A Primer of Mountain Geographies; Springer Nature: Bern, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Polynczuk-Alenius, K. Palimpsestic Memoryscape: Heterotopias, “Multiculturalism” and Racism in Białystok. Hist. Mem. 2022, 34, 33–75. [Google Scholar]

- Prober, S.M.; Doerr, V.A.; Broadhurst, L.M.; Williams, K.J.; Dickson, F. Shifting the conservation paradigm: A synthesis of options for renovating nature under climate change. Ecol. Monogr. 2019, 89, e01333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, N.P.; Clarke, J.; Orr, S.A.; Cundill, G.; Orlove, B.; Fatorić, S.; Sabour, S.; Khalaf, N.; Rockman, M.; Pinho, P.; et al. Decolonizing climate change–heritage research. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Frolich, L.M. (Eds.) The Elgar Companion to Geography, Transdisciplinarity and Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Glos, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia; Nus Press: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, A. The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science; Hachette: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Jones, H.; Herbert, K. Explorers’ Sketchbooks: The Art of Discovery; Chronicle: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, N.; Quesada-Román, A.; Granados-Bolaños, S. Mapping Mountain Landforms and Its Dynamics: Study Cases in Tropical Environments. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblom, A.; Shoemaker, A.; Gillson, L.; Lane, P.; Lindholm, K.J. Conservation through biocultural heritage—Examples from sub-Saharan Africa. Land 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O. Contesting Páramo: Critical Biogeography of the Northern Andean Highlands; Kona Publishers: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. Mongolia is home of the first national park in the world. Guard. Lett. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Schullery, P.; Whittlesey, L. Yellowstone’s creation myth: Can we live with own legends? Mont. Mag. West. Hist. 2003, 53, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sittler, M. Conservation Ethics: The Web Linking Human and Environmental Rights. Neb. Anthropol. 1999, 15, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, K. Myths of Wilderness in Contemporary Narratives: Environmental Postcolonialism in Australia and Canada; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, T. UNESCO’s experience with the protection of sacred natural sites for biodiversity conservation. In The Importance of Sacred Natural Sites for Biological Conservation, Paris (UNESCO), Proceedings of the International Workshop, Kunming and Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve, Kunming, China, 17–20 February 2003; Fuchsia Inc.: Paris, France; pp. 13–20.

- Leroux, S.J.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Schmiegelow, F.; Cumming, S.G.; Lisgo, K.; Anderson, L.G.; Petkova, M. Global protected areas and IUCN designations: Do the categories match the conditions? Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, D. Crafting nature: The Galapagos and the making and unmaking of a “natural laboratory”. J. Political Ecol. 2009, 16, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; González, J.A.; Lavilla, E.O.; Donoso, M.; Ibarra, J.T. Onomastic misnomers in the construction of faulty Andeanity and week Andeaness: Biocultural Microrefugia in the Andes. Pir. J. Moun. Ecol. 2019, 174, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, M.B.; McMichael, C.H.; Piperno, D.R.; Silman, M.R.; Barlow, J.; Peres, C.A.; Power, M.; Palace, M.W. Anthropogenic influence on Amazonian forests in pre-history: An ecological perspective. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetler, J.B. Imagining Serengeti: A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Morgera, E.; Tsioumani, E.; Buck, M. Unraveling the Nagoya Protocol: A Commentary on the Nagoya Protocol on Sccess and Benefit-Sharing to the Convention on Biological Diversity; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bernbaum, E. Sacred Mountains of the World, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, J.D. Sustainable Mountain Development: Getting the Facts Right; Springer Nature: Bern, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Inaba, N. Cultural landscapes in Japan: A century of concept development and management challenges. In Managing Cultural Landscapes; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Bernbaum, E.; Lennon, J.; Brown, J. Managing cultural uses and features. In IUCN’s Protected Area Governance and Management; Worboys, G., Lockwood, M., Kothari, A., Feary, S., Pulsford, I., Eds.; ANU Press: Sydney, Australia, 2015; pp. 686–714. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, V.; Ekblom, A.; Wästfelt, A. From landscape as heritage to biocultural heritage in a landscape, Chapter 7. In Landscape as Heritage: International Critical Perspectives; Pettenati, G., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L.; Hurni, H. Protected Areas in Mountains. Mt. Res. Dev. 2003, 23, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovjak, M.; Kukec, A. Health outcomes related to built environments. In Creating Healthy and Sustainable Buildings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, J.; Teeuwen, M. Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Botkin, D.B. Discordant Harmonies: A New Ecology for the Twenty-First Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, J.J. Making War to Keep Peace; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Belal, H.M.; Shirahada, K.; Kosaka, M. Value co-creation with customer through recursive approach based on Japanese Omotenashi service. Int. J. Bus. Admin. 2013, 4, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, D.; Rehdanz, K.; Welsch, H. (Eds.) Handbook on Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment; Edward Elgar: Chelktenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki, K. Harmonious co-existence between nature and mankind: An ideal lifestyle for sustainability carried out in the traditional Japanese spirit. Hum. Nat. 2008, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, M.R.P.; Ibarra, M.A.; Baltazar, E.B.; de Araujo, L.G. Local Socio-Environmental Systems as a Transdisciplinary Conceptual Framework. In Socio-Environmental Regimes and Local Visions: Transdisciplinary Experiences in Latin America; Springer-Cham: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, E.; Gillespie, J. Separating natural and cultural heritage: An outdated approach? Aust. Geogr. 2022, 53, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.M. Confirmative biophilic framework for heritage management. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M. Mountain Religion and Gender. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Association for the History of Religion (IAHR), The Association for the Study of Japanese Mountain Religion, Tokyo, Japan, 20–24 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, B.; Mallarach, J.M.; Bernbaum, E.; Spoon, J.; Brown, S.; Borde, R.; Brown, J.; Calamia, M.; Mitchell, N.J.; Infield, M.; et al. Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature: Guidance for Protected and Conserved Area Governance and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, P.A. Introduction: The Religious Orders Today. Soc. Compass 2001, 48, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation report of the boundary modification. In Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range; UNESCO-ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T. Influence of forestry on the formation of national park policy in Japan. J. For. Plan. 1996, 2, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentz, J. The Religious Situation in East Asia. In Secularization and the World Religions; Joas, H., Wiegandt, K., Eds.; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2009; pp. 241–277. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E.L. Spirit Tree: Origins of Cosmology in Shinto Ritual at Hakozaki; University Press of America: Langham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S.B. Field Guide to the Spirit World: The Science of Angel Power, Discarnate Entities, and Demonic Possession; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, F.; Redden, A. (Eds.) Angels, Demons and the New World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson, M.H. Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite; University of Washington Press: Seatle, WA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.E.; Liuzza, C.; Meskell, L. The politics of peril: UNESCO’s list of world heritage in danger. J. Field Archaeol. 2019, 44, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A. Franchising our heritage: The UNESCO world heritage brand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T. World Heritage Sites: Tourism, Local Communities and Conservation Activities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. The World Heritage Convention at 50: Management, credibility and sustainable development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, S.C.; Cooke, L. World Heritage: Concepts, Management and Conservation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK; Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, R.W. Periodic Reporting under the World Heritage Convention: Futures and Possible Responses to Loss. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 30, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L.; Liuzza, C. Saving the World: Fifty Years of the Convention, Conservation, and Collaboration. Change Over Time 2022, 11, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.; Riede, F. Upscaling Local Adaptive Heritage Practices to Internationally Designated Heritage Sites. Climate 2022, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, C. Climate Action and World Heritage: Conflict or Confluence? In 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility–Conflict & Reconciliation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 239–251. [Google Scholar]

| Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Agriscape | Holistic sphere of crop producing cycles of cultivation and rituals. | Haller & Branca 2020 [3] |

| Biocultural diversity | The many species of plants and animals that have been either created or domesticated and cohabiting the place of residence. | Eriksson 2018 [4] Rotherham 2015 [5] |

| Biocultural heritage | The collective of cherished memories of place, landscape and ecosystem that continue traditional lifestyles and ancient wisdom. | Ferrara et al. 2022 [6] |

| Consilience | The process tending to the unity of science, the ultimate wholistic approach of convergent knowledge. | Wilson 2008 [7] |

| Decolonial scholarship | Eliminates elitist and hegemonic legacies of colonial powers in favor of a pragmatic, inclusive, equitable and true integration of indigenous and traditional knowledge with the scientific corpus of Western science. | Pettenati 2022 [8] Longo 2022 [9] |

| Earth ethics | The interrelations, interactions and implications of people sharing the habitat with their habits towards the wellbeing of the coinhabitants. | Sarmiento & Hitchner. 2017 [10] |

| Ecological legacy | Process of familiarization and domestication that is passed from antiquity to modern communities | Ferrara et al. 2022 [6] |

| Farmscape transformation | Deep change in the condition of agricultural production towards other uses, with not only land-use change, but profound change in the lifescape and livelihood of the elements of the farm with the nearby forests. | Sarmiento et al. 2018 [11] |

| Fusion landscape | The summative characteristics of physical and cultural amalgamation toward an undistinguishable nature-culture linkage. | Sarmiento & Viteri 2015 [12] |

| Heritagization | Process of cultural and ecological appropriation of ancient identity markers and memory holders as tangible and intangible goods that form the essence of place | Pipan & Topole 2022 [13] |

| Heritagescape | The holistic sphere of interacting elements of tradition, ritual, mystic and cultural manifestations shared in a territory with deep intergenerational respect | Burlingame 2022 [14] |

| Historicity | The political ecology of the passing of time that marks significant steps taken to the present state of affairs. | Johnson & Davidson-Hunt 2011 [15] |

| Langscape | The holistic sphere of the interacting elements of language and linguistics of a mega diversity spoken and written forms of communication. | Sarmiento 2022 [16] |

| Manufactured landscape | The current landscape configuration resulting from the integration of natural and cultural processes in the creation of a significant place | Sarmiento 2020 [1] |

| Memoryscape | The holistic sphere of vivid experiences and cherished feelings associated with the development of the self as reflected by ancestors and knowledge keepers. | Polynczuk-Alenius 2022 [17] |

| Montology | Transdisciplinary and convergent mountain science, with transgressions of scientific disciplines and humanities and arts. | Sarmiento 2022 [16] |

| Mountainscape | The holistic sphere of multidimensional factors interacting to provide a novel epistemology of mountain systems. | Sarmiento 2022 [16] |

| Noetics | Part of the metaphysics that deals with the explanatory power of the unity of knowledge. | Prober et al. 2019 [18] |

| Socioecological system | Ecological properties triggered by social and cultural factors that render complex adaptations ds | Sarmiento 2020 [1] |

| Soundscape | The holistic sphere of sounds, noise, music, and other types of vibrations of the auditive wave. | Pinho & Maharaj 2022 [19] |

| Spatiality | Processes modifying the spatial dimension towards the creation of place. | Sarmiento & Frolich 2020 [20] |

| Territoriality | Tendency of biophilic organisms to defend the place for reproductive success. In heritage studies sometimes territory is defined as the rigid fabric of the community. | Sarmiento 2020 [1] |

| Transdisciplinary | Integrative approach to use the scalar of disciplines to obtain the cross-cutting of themes and convergence of methodologies by western science and indigenous ecological knowledge. | Sarmiento & Frolich 2020 [20] |

| Transgressivity | Propensity of breaking boundaries of disciplines otherwise locked in their own silos. Transgression is the first condition of transdisciplinarity | Sarmiento 2022 [16] |

| Zomia | Mythical place in the mountains of South East Asia, where indigenous communities live in a paradisiacal anarchy due to isolation and marginality, | Scott 2009 [21] |

| Term | Construct | Inversed Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Sustainable development | Easily explained when unsustainable practices affect the mountain socioecological system = damaged or unsustainable. | Hamilton & Hurni 2003 [43] |

| Health | Environmental health | Easily explained when sickness and disease is apparent in the mountain environment = unhealthy. | Dovjak & Kukec. 2019 [44] |

| Kami | Spiritual essence | Easily explained when no religious or spiritual reaction is observed in the presence of mountain features = unanimated, atheist. | Breen & Teeuwen 2001 [45] |

| Harmony | Natural harmony | Easily explained when disruption in the balance break the equilibrium in the mountain ecosystem = disequilibrium, chaos. | Botkin 1990 [46] |

| Peace | Pax Americana | Easily explained when violent acts and criminality pervade neighborhoods in the United States = revolts, insurgence and crime. | Kirkpatrick 2007 [47] |

| Omotenashi | Japanese hospitality | Easily explained by rude stares and lackadaisical bows to mountain tourists = non attentive. | Belal et al. 2013 [48] |

| Happiness | Satisfactory wellbeing | Easily explained when welfare malfunctions affect largely the emotions of mountain people = sadness, boredom. | Maddison et al. 2020 [49] |

| Okuyama | Deep mountain recess | Easily explained when climbing does not get to a resting state, bringing tiredness and boring distractions in the mountain slopes = unreachable paradise. | Iwatzuki 2008 [50] |

| MAJOR PLAYERS | DECADAL ADVANCE OF MONTOLOGY | ||||||

| GLOBAL NORTH | 60s | 70s | 80s | 90s | 00s | 10s | 20s |

| Carl Troll (DE) | |||||||

| Jack D. Ives (CA) | |||||||

| Eugene P. Odum | |||||||

| Bruno Messerli (CH) | |||||||

| Maurice Strong (UNEP) | |||||||

| Carol Harden (US) | |||||||

| Lawrence Hamilton (US) | |||||||

| Axel Borsdorf (AT) | |||||||

| Robert Rhoades (US) | |||||||

| Bernard Debarbieux (FR) | |||||||

| Teiji Watanabe (JP) | |||||||

| Jörg Balsinger (CH) | |||||||

| Zev Naveh (IL) | |||||||

| Nigel Allan (US) | |||||||

| Edwin Bernbaum (US) | |||||||

| Hermann Kreutzmann (DE) | |||||||

| Christoph Stadel (CA-AT) | |||||||

| Martin Price (UK) | |||||||

| Monique Fort (FR) | |||||||

| José María García Ruiz (ES) | |||||||

| Alton Byers (US) | |||||||

| Thomas Schaaf (DE) | |||||||

| Hans Hurni (CH) | |||||||

| Yuri Badenkov (RU) | |||||||

| Donald Friend (US) | |||||||

| Thomas Kohler (CH) | |||||||

| Alexey Gunya (RU) | |||||||

| GLOBAL SOUTH | |||||||

| Gerardo Budowski (CR-VE) | |||||||

| Misael Acosta-Solís (EC) | |||||||

| Trilok Singh Papola (IN) | |||||||

| Fausto Sarmiento (US-EC) | |||||||

| Víctor Toledo (MX) | |||||||

| Hugo Romero (CL) | |||||||

| Mesfin Woldemariam (ET) | |||||||

| Radu Rey (RO) | |||||||

| J. Gabriel Campbell (NP) | |||||||

| Guangyu Huang (CN) | |||||||

| Irasema Alcántara-Ayala (MX) | |||||||

| Esther Njiro (ZA) | |||||||

| Constanza Ceruti (AR) | |||||||

| Gustavo Martinelli (BR) | |||||||

| Virginia Nazarea (PH) | |||||||

| Elías Mujica (PE) | |||||||

| Arturo Eichler (VE-DE) | |||||||

| Eduardo Gudynas (UR) | |||||||

| Ricardo Rozzi (CL-US) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarmiento, F.O.; Inaba, N.; Iida, Y.; Yoshida, M. Mountain Graticules: Bridging Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Historicity to Biocultural Heritage. Geographies 2023, 3, 19-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3010002

Sarmiento FO, Inaba N, Iida Y, Yoshida M. Mountain Graticules: Bridging Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Historicity to Biocultural Heritage. Geographies. 2023; 3(1):19-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmiento, Fausto O., Nobuko Inaba, Yoshihiko Iida, and Masahito Yoshida. 2023. "Mountain Graticules: Bridging Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Historicity to Biocultural Heritage" Geographies 3, no. 1: 19-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3010002

APA StyleSarmiento, F. O., Inaba, N., Iida, Y., & Yoshida, M. (2023). Mountain Graticules: Bridging Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Historicity to Biocultural Heritage. Geographies, 3(1), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3010002