An AI-Driven TiO2-NiFeC-PEM Microbial Electrolyzer for In Situ Hydrogen Generation from POME Using a ZnO/PVA-EDLOSC Nanocomposite Photovoltaic Panel

Abstract

1. Introduction

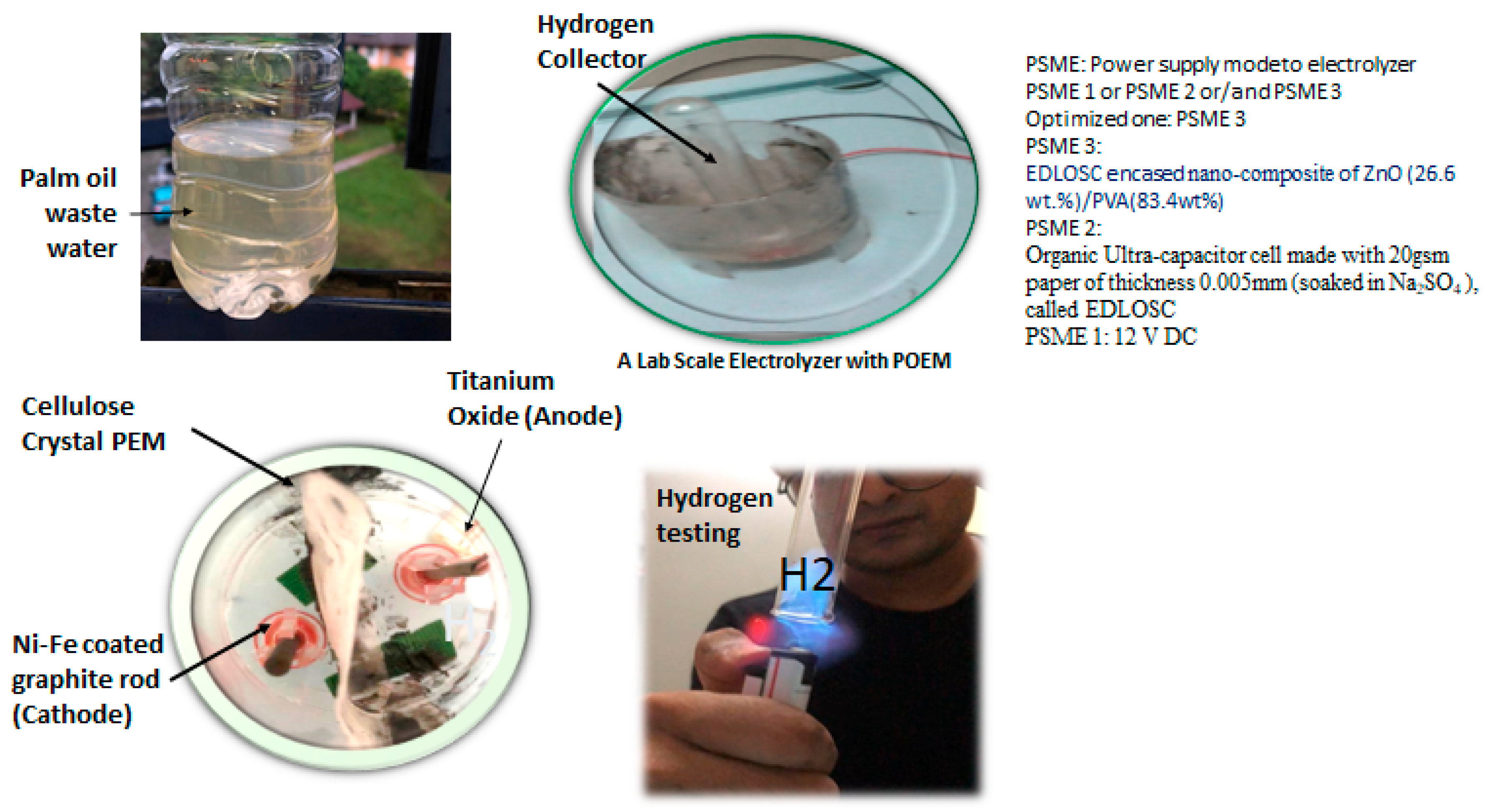

2. Methodology

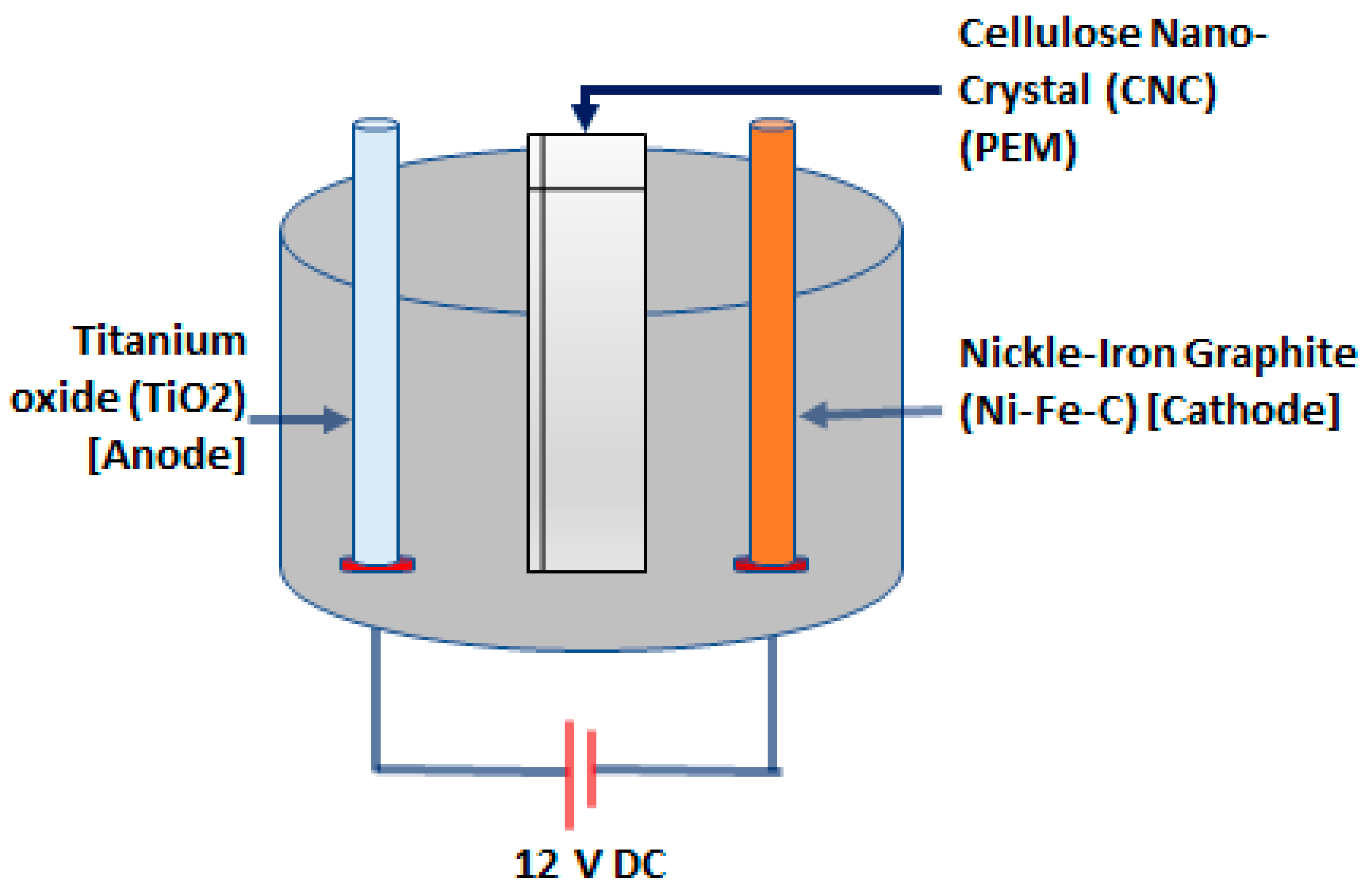

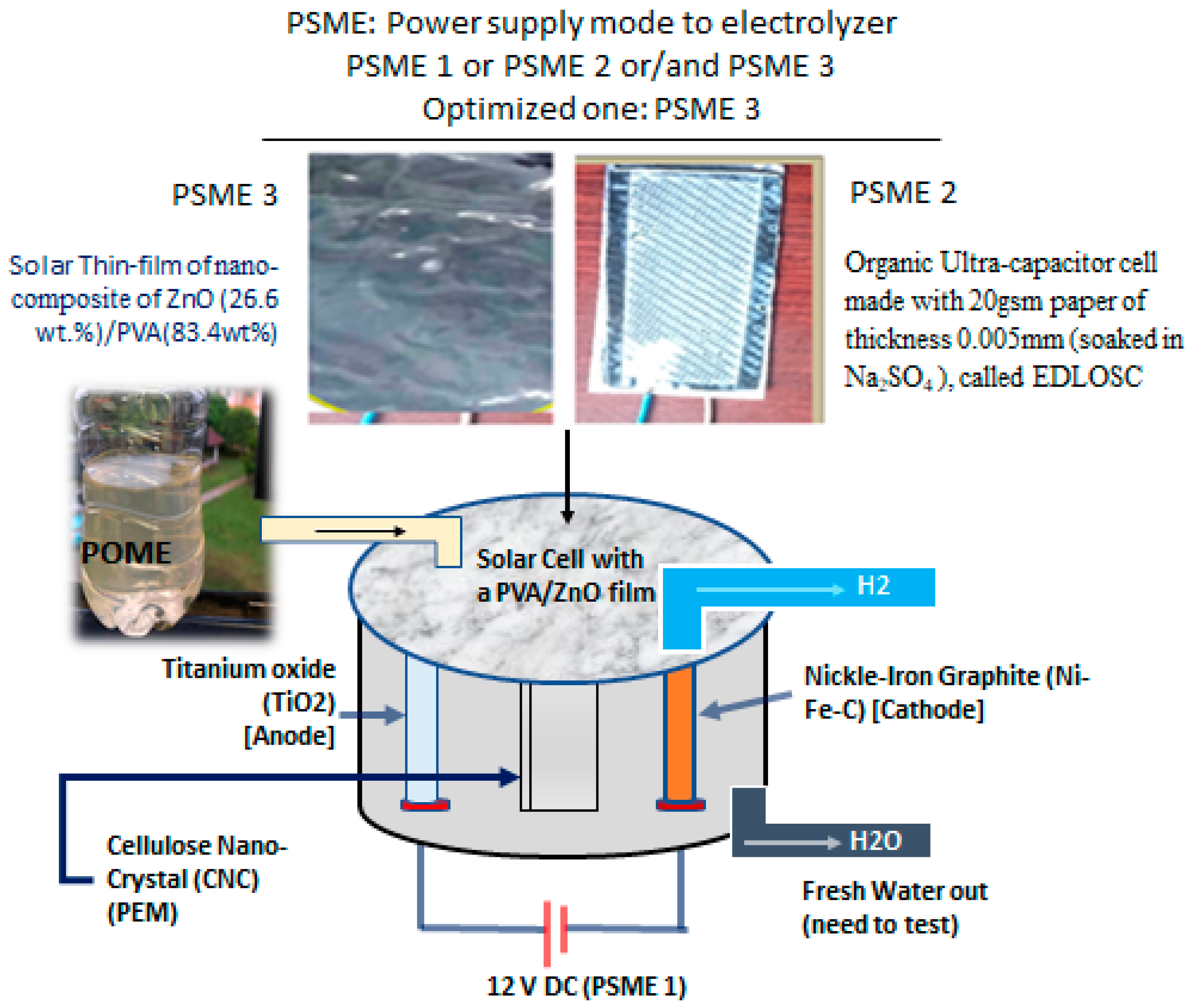

- PSME 1: A 12 V DC lead gel battery is defined as the power supply mode to the electrolyzer;

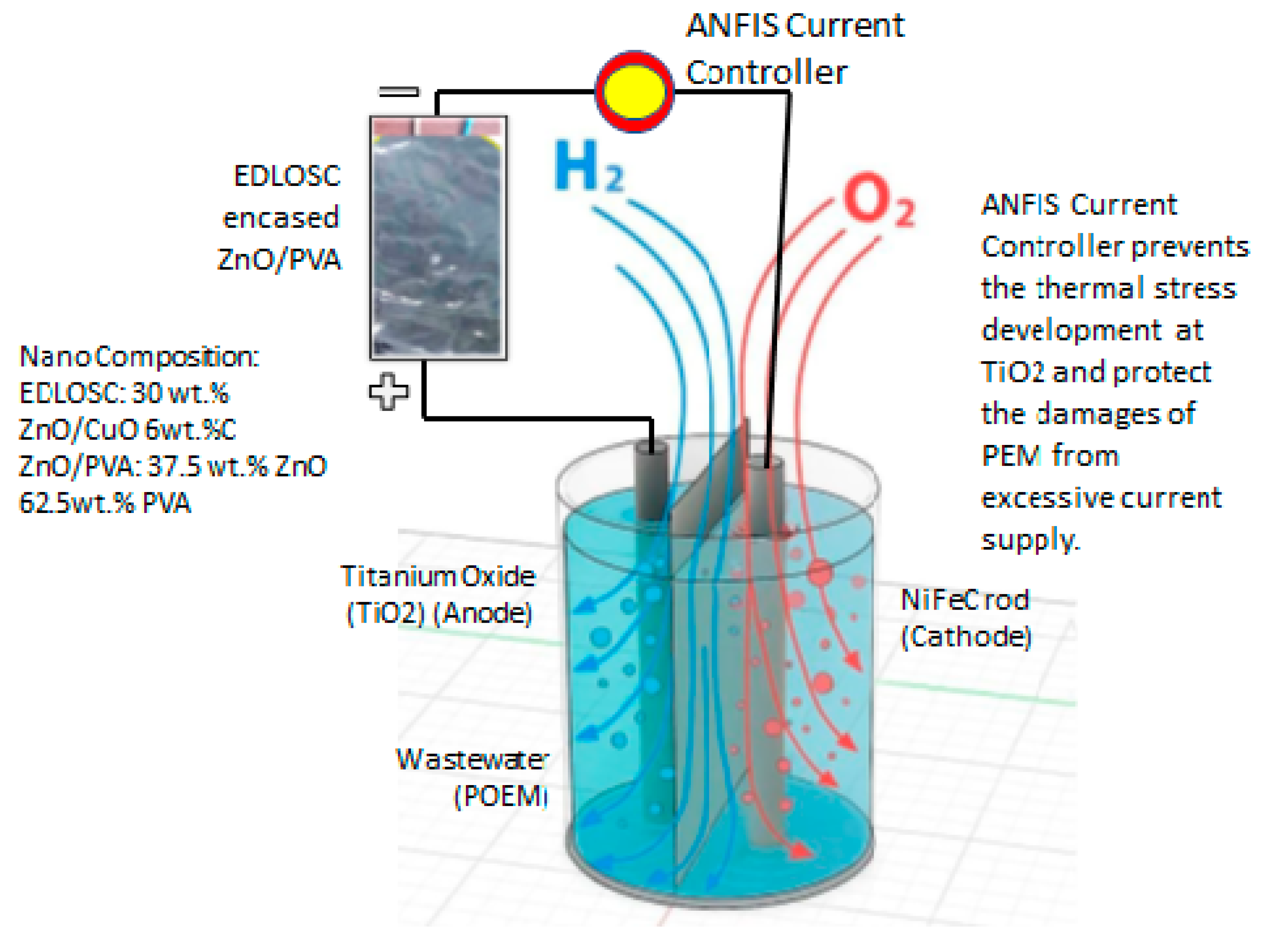

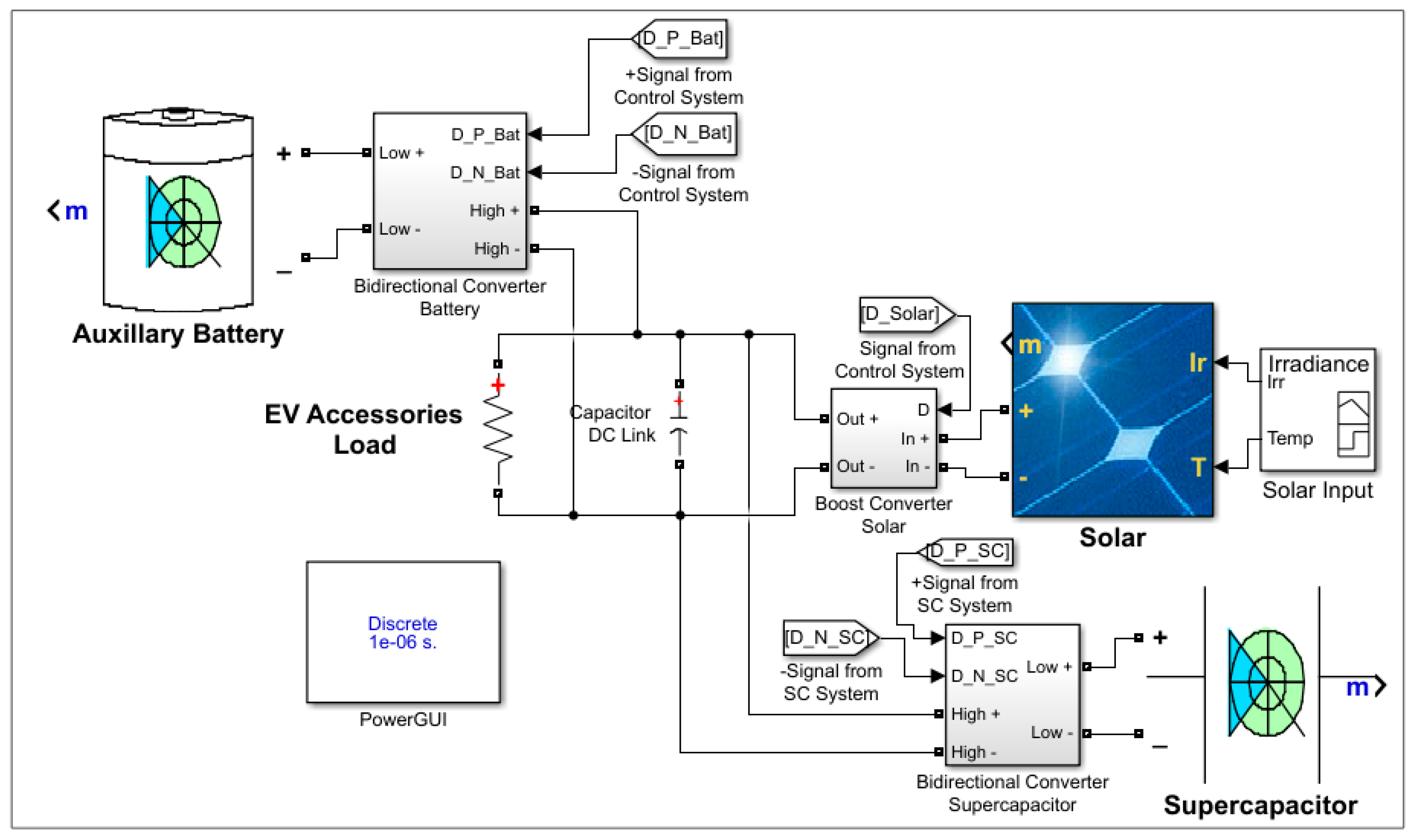

- PSME 2: A solar-dependent aqueous electric double-layer organic solar capacitor (EDLOSC) plus a 12 V battery;

- PSME 3: A solar-dependent EDLOSC integrated with ZnO/PVA plus a 12 V battery.

2.1. Organic Power System of the TiO2-NiFe CNC-PEM Electrolyzer

2.2. Performance of the Organic Power System in Hydrogen Generation

2.3. Comparison of EDLOSC with the Published Related Product

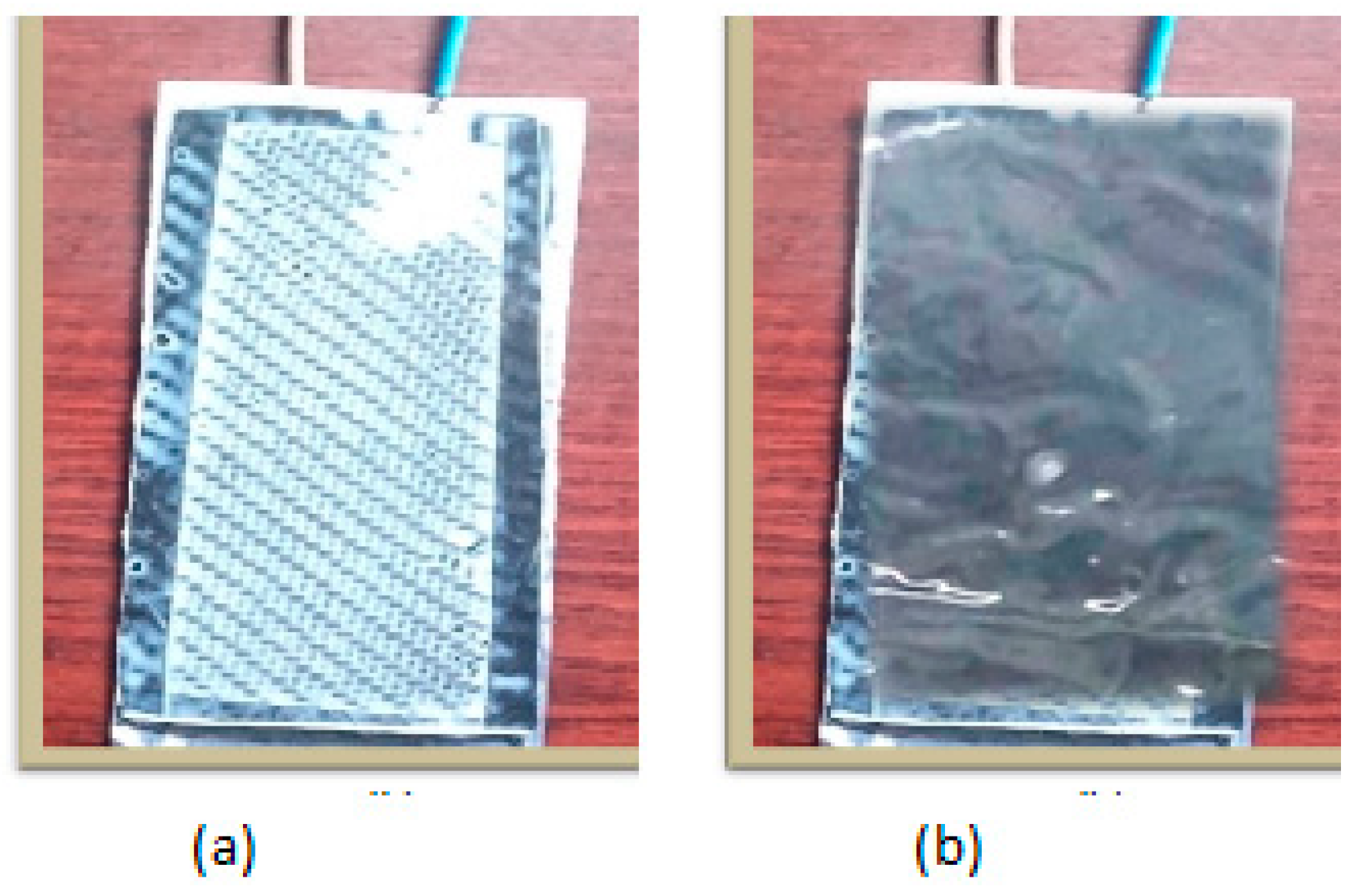

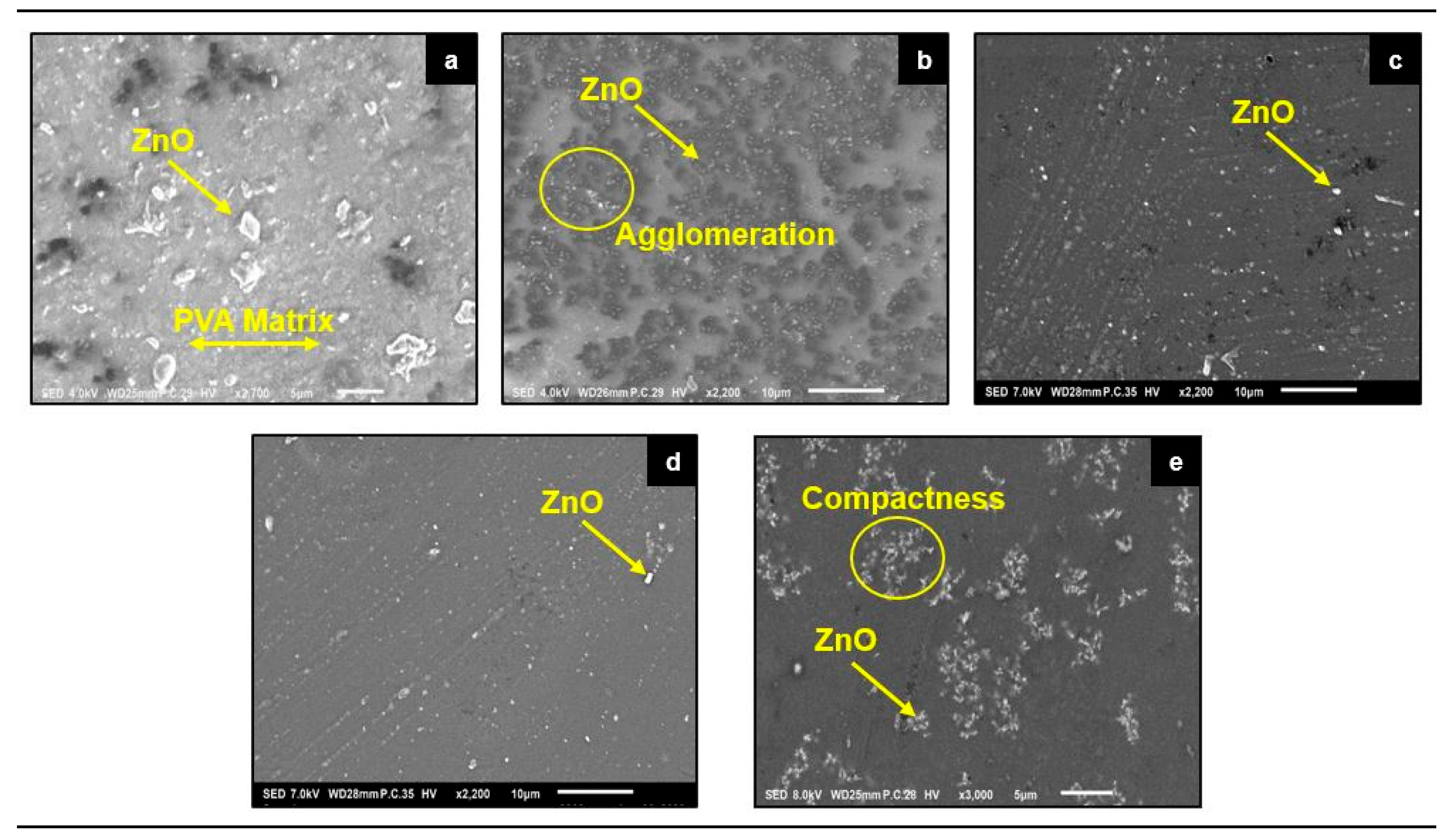

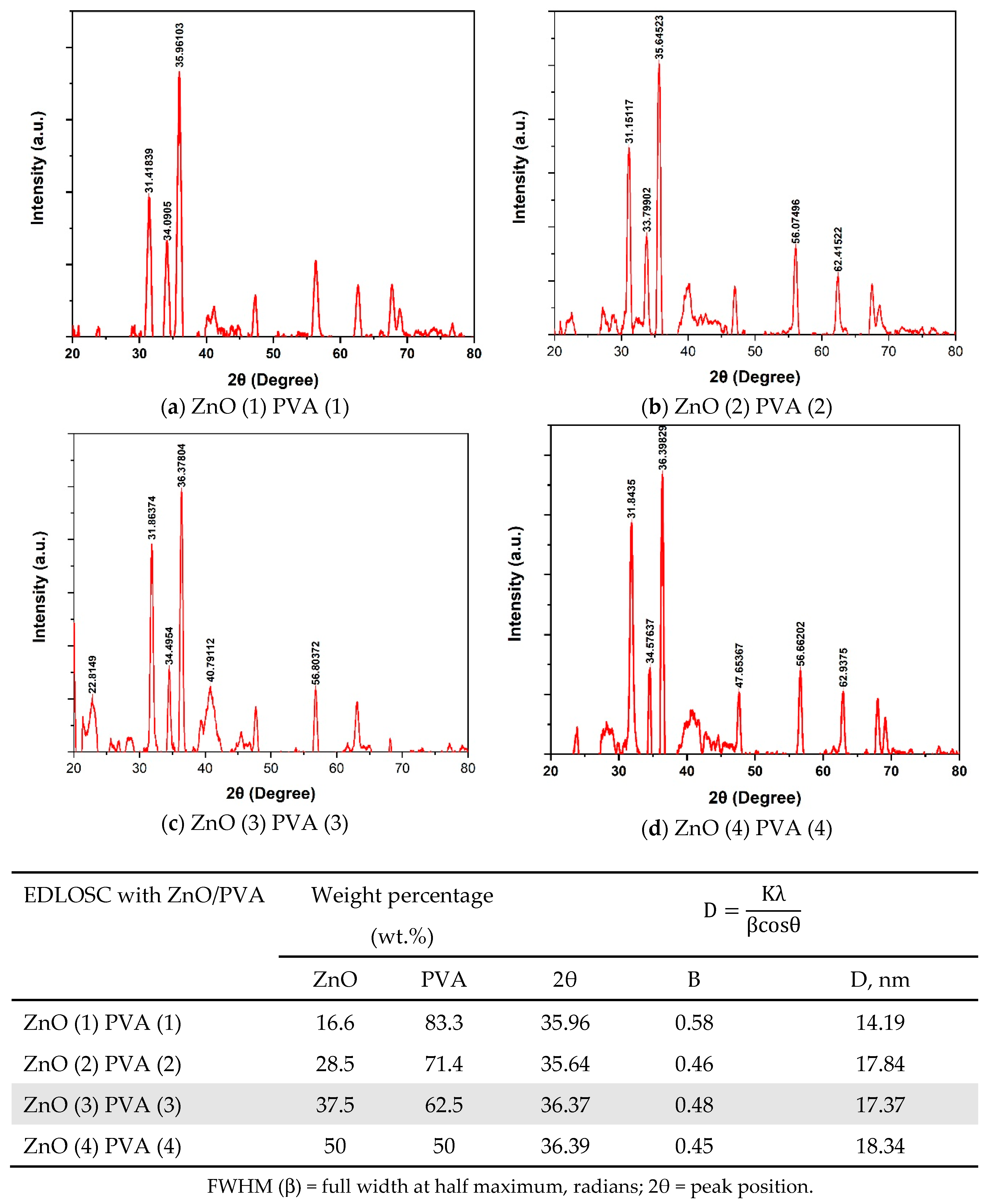

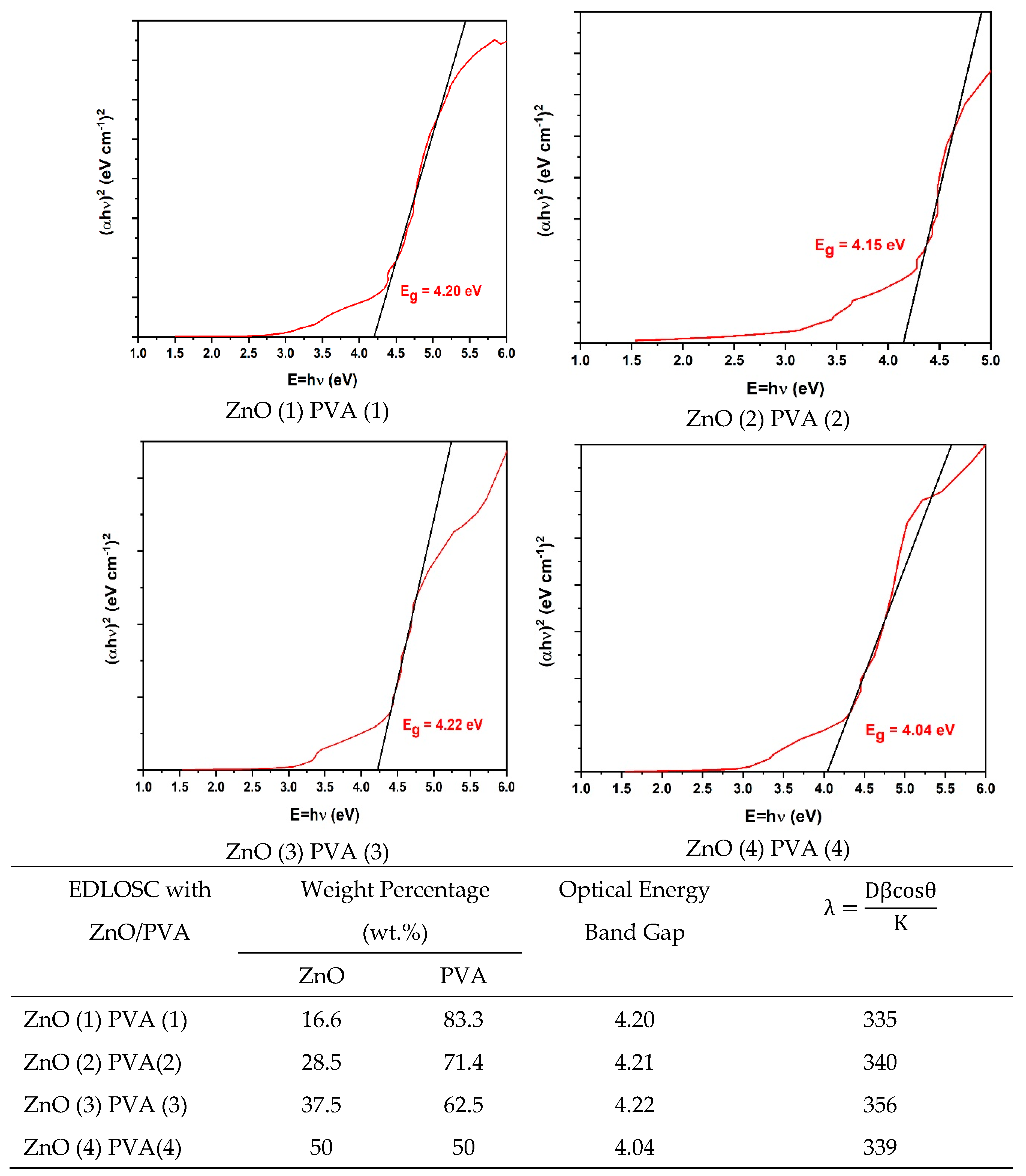

Characterization of EDLOSC-Encased ZnO/PVA

| EDLOSC * PVA/ZnO | Weight Percentage (wt.%) | |

| ZnO | PVA | |

| ZnO (1) PVA (1) | 16.6 | 83.3 |

| ZnO (2) PVA(2) | 28.5 | 71.4 |

| ZnO (3) PVA (3) | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| ZnO (4) PVA (4) | 50 | 50 |

| EDLOSC *: Nano-structure of 6 wt.% C 30 wt.% ZnO/CuO with Na2SO4 soaked aqueous 70 gsm. | ||

3. Parametric Study

4. Performance Investigation

- PSME 1: A 12 V DC lead gel battery;

- PSME 2: A solar-dependent aqueous electric double-layer organic solar capacitor plus battery;

- PSME 3: A solar-dependent EDLOSC integrated with ZnO/PVA plus battery.

- Carbon (C): 7 atoms × 12.01 g/mol = 84.07 g/mol;

- Hydrogen (H): 15 atoms × 1.01 g/mol = 15.15 g/mol;

- Oxygen (O): 5 atoms × 16.00 g/mol = 80.00 g/mol;

- Phosphorus (P): 1 atom × 30.97 g/mol = 30.97 g/mol.

- Water electrolysis has high theoretical H2 yield per mole of substrate but requires electrical energy input.

- POME-based microbial electrolysis produces less H2 per gram of substrate, but it treats waste and can utilize chemical energy stored in organics, reducing external energy input.

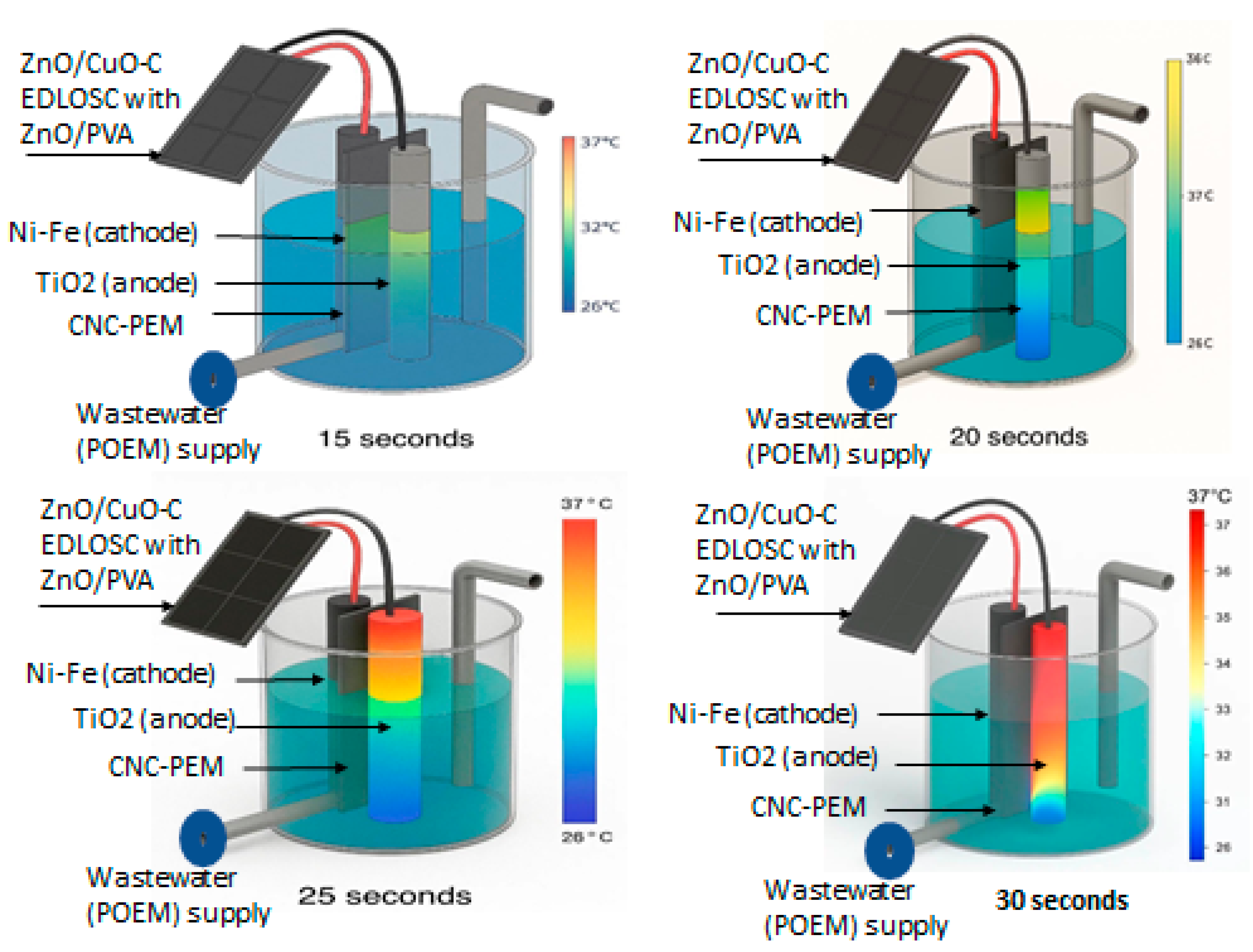

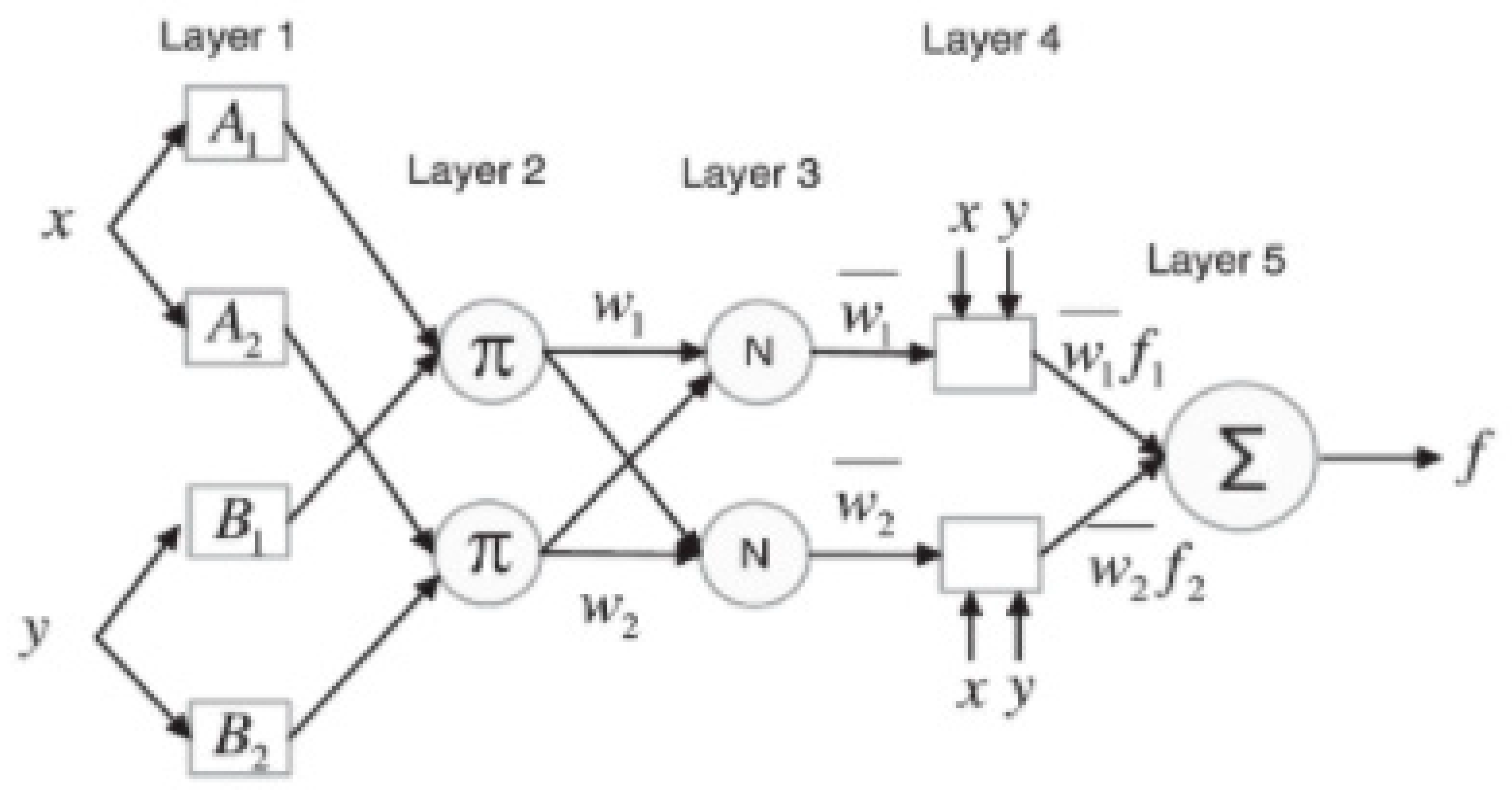

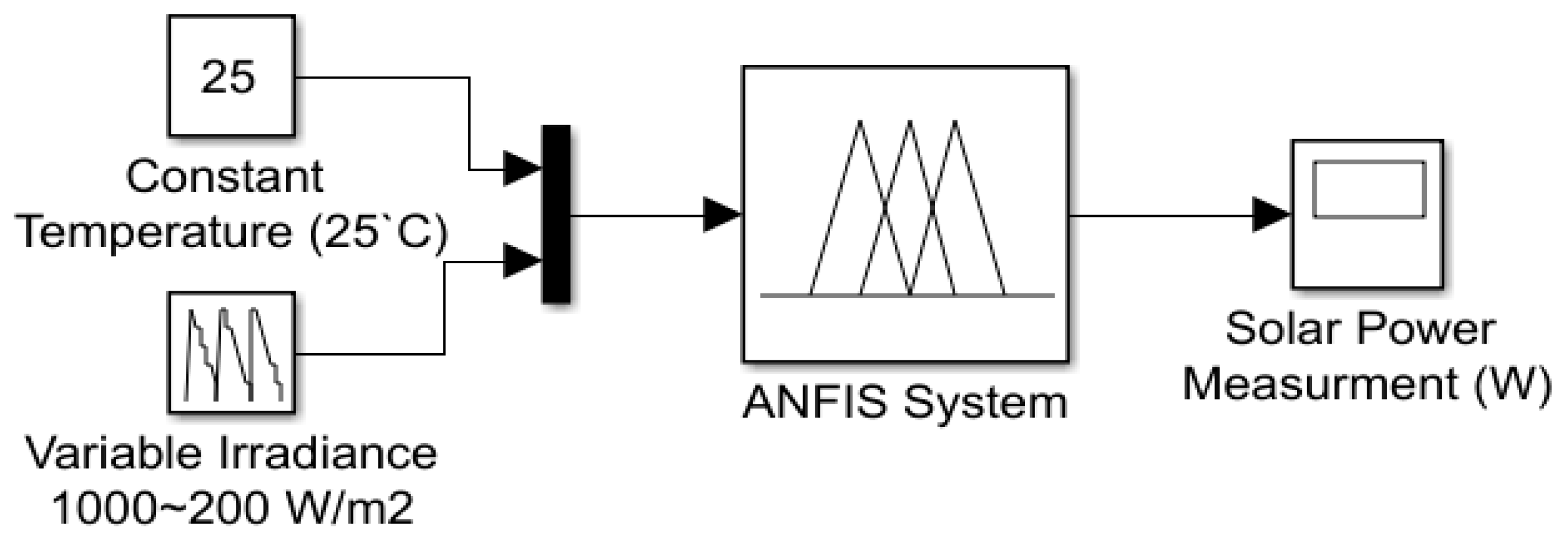

5. AI (ANFIS) Power Driven

- To control the EDLOSC power flow to the ME to protect the PEM from damage.

- To prevent the EDLOSC from overcharging when trapping solar heat above 32 °C.

- To optimize power supply to the ME to prevent PEM from being affected.

- To control the POME supply to the ME based on the temperature and current supply in every 25 s, which will enhance the hydrogen generation and increase the sustainability of ME.

6. Conclusions

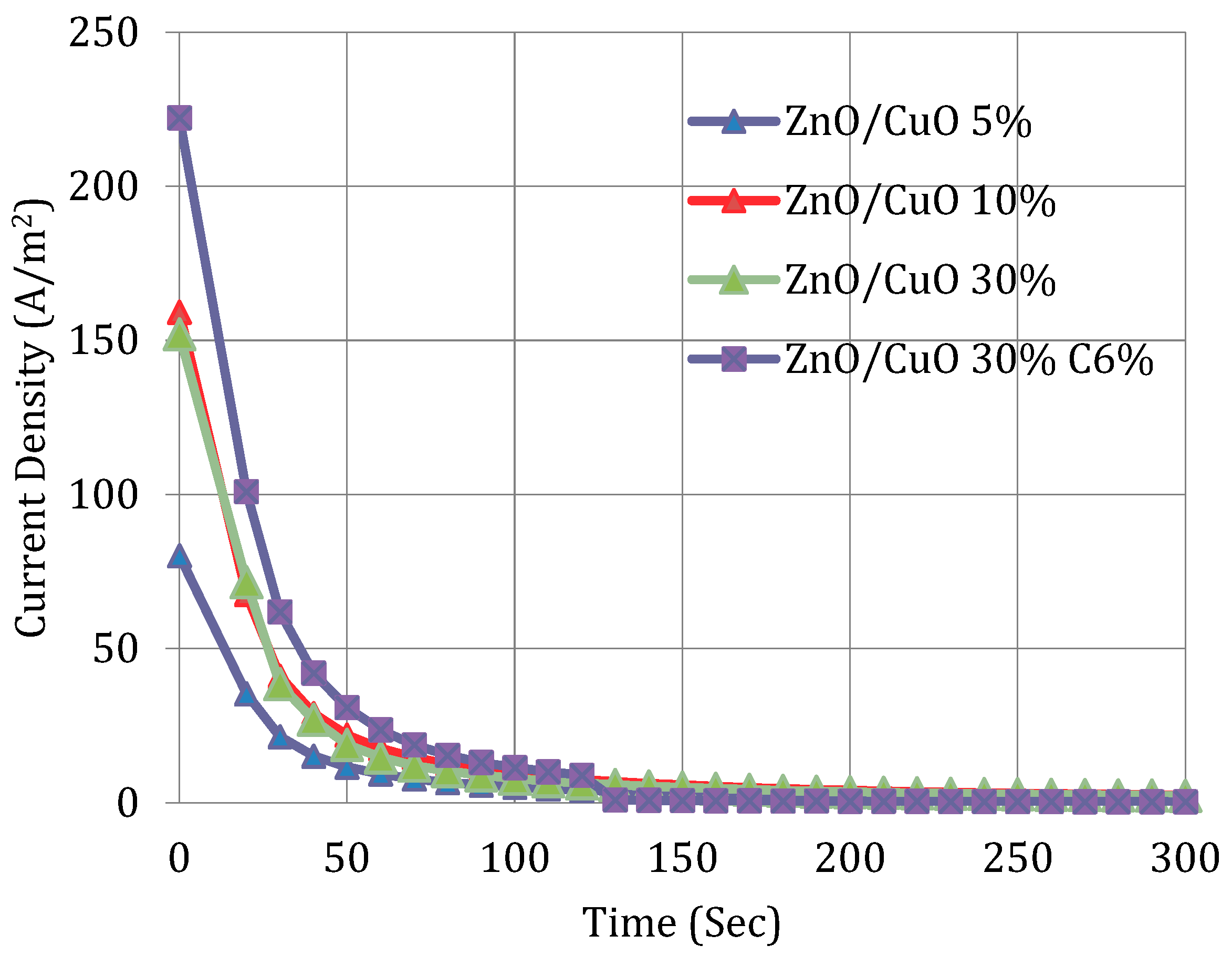

- The discharging time of the organic EDLC is longer compared to its charging time, primarily due to the AC-ZnO/CuO composite being bonded with epoxy resin (ER), which influences ion mobility and charge retention.

- The electrolyzer performance in terms of hydrogen generation using the ZnO/PVA-encased EDLOSC was 0.5% higher per mole compared to the 12 V DC supply, and 0.2% higher compared to the standalone EDLOSC.

- The PMS utilizing an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) can divert surplus power to the ground by connecting the EDLOSC to a grounding path, which allows the EDLOSC to operate efficiently and safely as an auxiliary energy storage unit.

- The TiO2–NiFeC CNC-PEM microbial electrolyzer achieves higher in situ hydrogen production from POME: 3.29% above the theoretical estimate when powered by a 12 V DC battery, 3.59% higher when powered by the EDLOSC, and 3.79% higher when powered by the EDLOSC integrated with ZnO/PVA.

6.1. Indexing: In Situ Hydrogen Production

6.2. Challenges

- The development of the TiO2-NiFeC-PEM microbial electrolyzer integrated with an organic solar energy capacitor involves high material, fabrication, and system integration costs. The complexity of combining microbial, electrochemical, and photovoltaic components significantly increases research and development expenses, necessitating substantial financial support such as grants from the Department of Energy (DOE) to advance the technology toward commercialization.

- Scale-up of TiO2-NiFeC-PEM microbial electrolyzer cells (MECs), volumetric current density, and hydrogen production rates decline significantly compared to lab-scale performance.

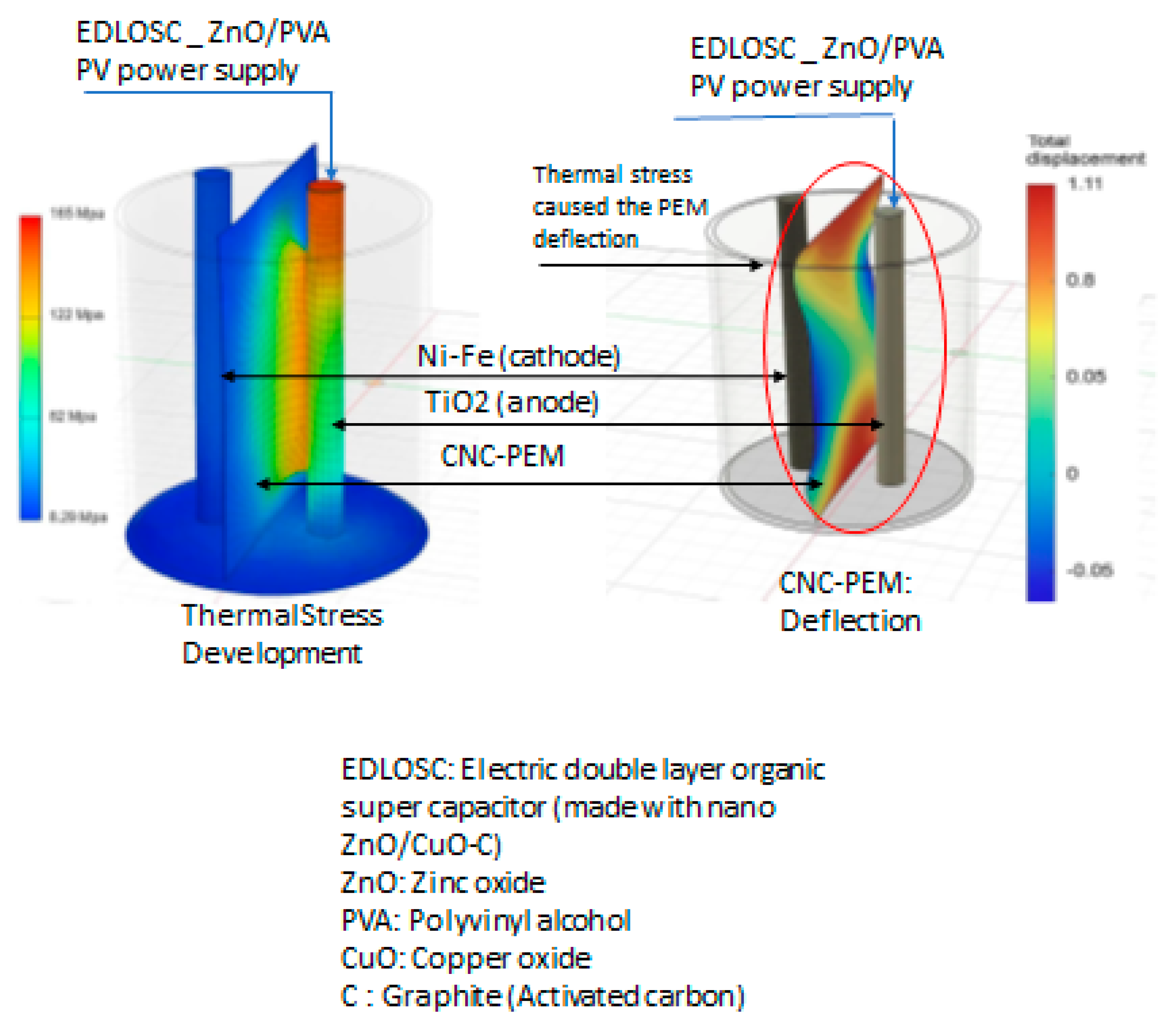

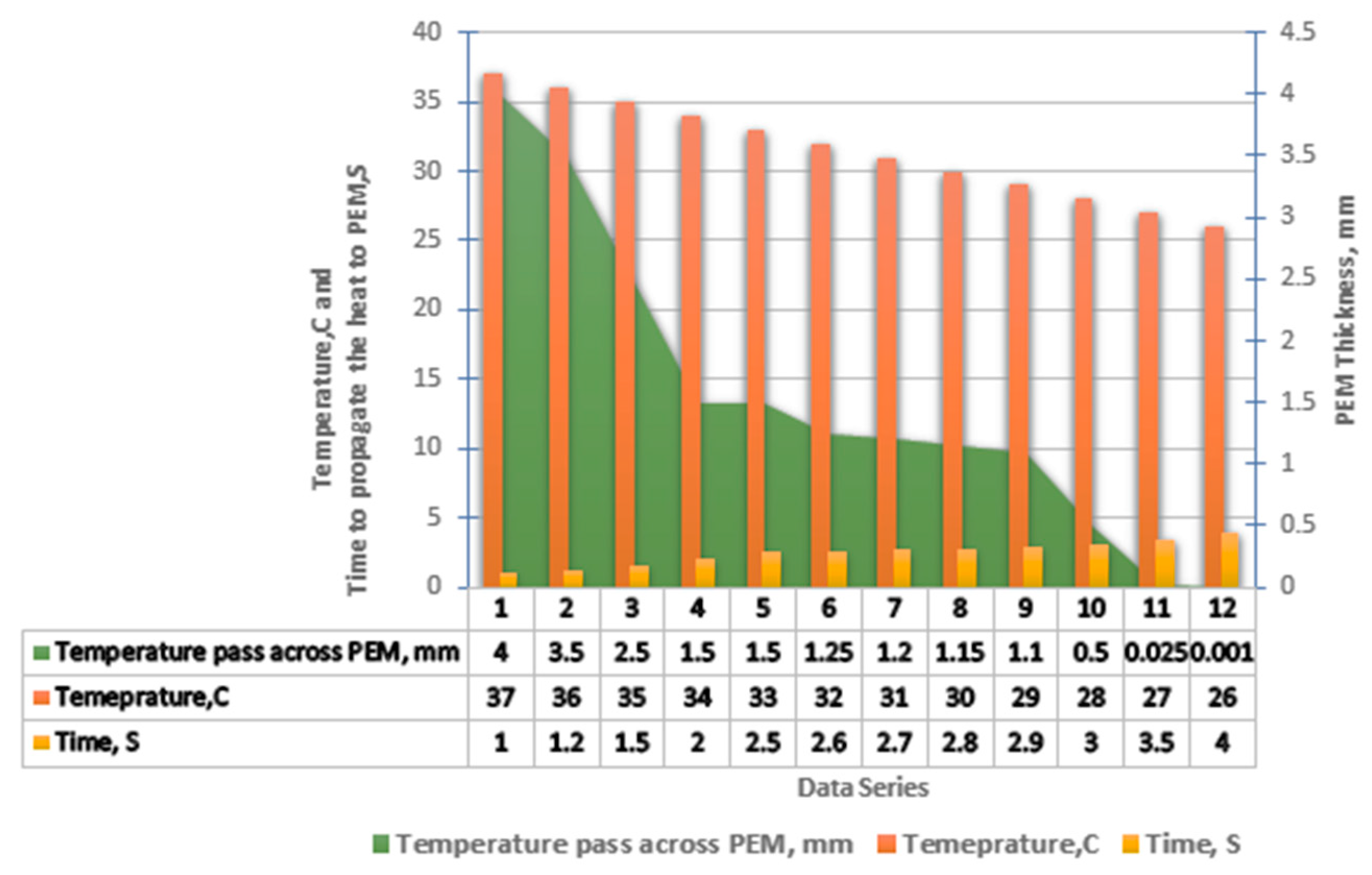

- Operating at excessive current densities can generate localized thermal stress within the proton exchange membrane (PEM), accelerating its mechanical and chemical degradation. This deterioration adversely affects ionic conductivity and may ultimately compromise the electrolyzer’s hydrogen production performance.

- Integration of the microbial elements with electrochemical elements including the organic solar energy capacitor brings additional material compatibility, which complicates electrode design.

- The in situ hydrogen yield obtained from the ME powered by the solar-dependent EDLOSC is approximately 30% lower than the theoretical prediction, primarily due to losses associated with manual hydrogen collection.

6.3. Novelties

- EDLOSC (ZnO/CuO RP with encased solar film made with ZnO/PVA) to provide the power supply to the ME in situ H2 production.

- AI (ANFIS) controls and optimizes the power supply to the ME to protect the PEM from damage at higher solar heat.

- AI protects the EDLOSC from damage from overcharging at higher power at higher solar trapping heats above 32 °C.

- Control the POME flow to the ME based on the temperature and current supply.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mussio, I.; Chilton, S.; Duxbury, D.; Nielsen, J.S. A risk–risk trade-off assessment of climate-induced mortality risk changes. Risk Anal. 2024, 44, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Zuckerman, G.R.; Pinchuk, P.; Gleason, M.; Rivers, M.; Roberts, O.; Williams, T.; Heimiller, D.; Thomson, S.-M.; Mai, T.; et al. Renewable Energy Technical Potential and Supply Curves for the Contiguous United States: 2024 Edition; NREL Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-91900; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arisht, S.N.; Mahmod, S.S.; Abdul, P.M.; Indera, A.A.; Lay, C.H.; Silvanamy, H.; Sittijunda, S.; Jashim, J.M. Enhancing biohydrogen gas production in anaerobic system gas: Comparative chemical pre-treatment on palm oil mill effluent (POME). J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNouss, A.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. Enhancing waste to hydrogen production through biomass feedstock blending: A techno-economic-environmental evaluation. Appl. Energy 2020, 266, 114885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.; Anda, M.; Shafiullah, G.M. Hydrogen production for energy: An overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 3847–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyapal, S. Clean Hydrogen and Environmental Justice. U.S. Department of Energy—Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/clean-hydrogen-and-environmentaljustice (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- U.S. Congress. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Public Law 117-58, §40314, 135 Stat. 429, 15 November 2021. [Online]. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Idaho National Laboratory (INL). Hydrogen—Integrated Energy. 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://inl.gov/integrated-energy/hydrogen/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Martin, P. What is good hydrogen policy? The U.S. clean hydrogen tax credits. Hydrogen Science Coalition, 17 November 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://h2sciencecoalition.com/blog/good-hydrogen-policy-us-clean-hydrogen-tax-credits/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Seifert, K.; Waligorska, M.; Laniecki, M. Brewery wastewaters in photobiological hydrogen generation in presence of Rhodobacter sphaeroides O.U. 001. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 4085–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagir, E.; Ozgur, E.; Gunduz, U.; Eroglu, I.; Yucel, M. Single-stage photofermentative biohydrogen production from sugar beet molasses by different purple non-sulfur bacteria. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, N.; Jana, A.K.; Das, D.; Saikia, D. Photofermentative molecular biohydrogen production by purple-non-sulfur (PNS) bacteria in various modes: The present progress and future perspective. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 6853–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; You, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q. Bio-hydrogen production from apple waste by photosynthetic bacteria HAU-M1. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 13399–13407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, J.; Yan, M.; Tong, Y.W.; Wang, C.W.; Wang, X. Organic waste to biohydrogen: A critical review from technological development and environmental impact analysis perspective. Appl. Energy 2019, 256, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, E.; Asada, Y.; Arai, T.; Miyake, J. Light penetration into cell suspensions of photosynthetic bacteria and relation to hydrogen production. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1995, 80, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S. A review on production, storage of hydrogen and its utilization as an energy resource. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Dincer, I.; Crawford, C. A review on hydrogen production and utilization: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 26238–26264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, D.-J.; Zhou, X.; Jing, Y.; Ge, X.; Jiang, D.; Hu, J.; He, C. Photo-fermentative hydrogen production from crop residue: A mini review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 229, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, A.A.; Tavares, F.; Alves, M.M.; Cavaleiro, A.J.; Pereira, M.A. Garden and food waste co-fermentation for biohydrogen and biomethane production in a two-step hyperthermophilic–mesophilic process. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, H.S.; Jung, K.W. Effect of temperature on continuous fermentative hydrogen production from Laminaria japonica by anaerobic mixed cultures. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 144, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.; Nasr, M.; Abdelrazek, E.; Awad, H.M.; Zhaof, S.; Meng, F.; Tawfik, A. Techno-economic feasibility of energy-saving self-aerated sponge tower combined with up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor for treatment of hazardous landfill leachate. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 37, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, A.; Elreedy, A.; Fujii, M.; Ibrahim, M.G.; Tawfik, A. Robustness of anaerobes exposed to cyanuric acid contaminated wastewater and achieving efficient removal via optimized co-digestion scheme. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 24, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, M.B.; Logeshwaran, N.; Prabhakaran, S.; Kim, A.R.; Kim, D.H.; Yoo, D.J. Low-cost hydrogen production from alkaline/seawater over a single-step synthesis of Mo3Se4–NiSe core–shell nanowire arrays. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fede, G.; Collina, G.; Tugnoli, A.; Bucelli, M.; Daniel, F.; Silva, F.; Sgarbossa, F. Hydrogen supply design for the decarbonization of energy-intensive industries addressing cost, inherent safety and environmental performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 175, 151373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Rahman, A. The impact of ZnO/PVA solar film on the enhancement of organic solar panel efficiency. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Global Hydrogen Review 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iro, Z.S.; Subramani, C.; Dash, S.S. A brief review on electrode materials for supercapacitor. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 10628–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, A.; Nyholm, L.; Sjödin, M.; Strømme, M.; Mihranyan, A. Paper-based energy-storage devices comprising carbon fiber-reinforced polypyrrole–Cladophora nanocellulose composite electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparaj, V.L.; Shaijumon, M.M.; Kumar, A.; Murugesan, S.; Ci, L.; Vajtai, R.; Linhardt, R.J.; Nalamasu, O.; Ajayan, P.M. Flexible energy storage devices based on nanocomposite paper. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13574–13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.H.; Hu, L.B.; Vosgueritchian, M.; Wang, H.L.; Xie, X.; McDonough, J.R.; Cui, X.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z.N. Solution-processed graphene/MnO2 nanostructured textiles for high-performance electrochemical capacitors. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2905–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Rakhi, R.B.; Hu, L.B.; Xie, X.; Cui, Y.; Alshareef, H.N. High-performance nanostructured supercapacitors on a sponge. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5165–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhara, A.; Bibhutibhushan, S.; Basak, A.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Nillohit, M. Core–shell CuO–ZnO p–n heterojunction with high specific surface area for enhanced photoelectrochemical energy conversion. Sol. Energy 2016, 135, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.F.; Mansour, S.F.; Abdo, M.A. Improvement of structural and optical properties of ZnO/PVA nanocomposites. IOSR J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 7, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kandulna, R.; Choudhary, R.B. Concentration-dependent behaviors of ZnO-reinforced PVA–ZnO nanocomposites as electron transport materials for OLED application. Polym. Bull. 2018, 75, 3089–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Aung, K.M. Development of solar supercapacitor by utilizing organic polymer and metal oxides for subsystem of electric vehicle. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 125301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Afroz, R.; Jafar, A.H. Green Transportation System, 1st ed.; IIUM Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ataur, R.; Sany, I.I.; Jashi, F.; Driveline, A. Autonomous Driveline: Electric & Autonomous Electric Vehicle; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Aung, M.K.M.; Ihsan, S.; Shah, R.A.; Qubeissi, R.M.A.L.M.; Aljarrah, M.T. Solar energy dependent supercapacitor system with ANFIS controller for auxiliary load of electric vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, A.; Ma, X.; Yang, H.; Guo, L. Single-stage photofermentative hydrogen production from hydrolyzed straw biomass using Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 13810–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Ge, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q. Photo-fermentative hydrogen production from enzymatic hydrolysate of corn stalk pith with a photosynthetic consortium. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 16778–16785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Singh, S.P.; Asthana, R.K.; Singh, S. Biohydrogen production from sugarcane bagasse by integrating dark- and photo-fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 152, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Capacitance of OSC (µF) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% ZnO/CuO 0 wt.% C | 30% ZnO/CuO 0 wt% C | 30% ZnO/CuO 6 wt% C | |

| Dielectric OSC | |||

| Capacitance (µF) | 0.55 | 2.1 | 6.1 |

| EDLOSC | |||

| Capacitance (µF) | 346 | 510 | 578 |

| EDLOSC-encased ZnO/PVA | |||

| Capacitance (µF) | - | - | 606 |

| Performance of EDLOSC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voc (mV) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Fill Factor (FF) | Efficiency (η), | |

| EDLOSC | 570.88 | 24.6 | 64.22% | 11.01% |

| EDLOSC-encased ZnO/PVA | 662.81 | 31.46 | 73.3% | 16.65% |

| Carbonaceous Material | Electrolyte | Double-Layer Capacitance (µF/cm2) | Surface Area g/m2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published Product | ||||

| Activated carbon | 10% NaCl | 19 | 1200 | [27] |

| Carbon black | 1 M H2SO4 3.1 wt.% KOH | 8~10 | 230 | |

| Graphite powder | 10% NaCl | 35 | 4 | |

| Graphite cloth | 0.168 N NaCl | 10.7 | 630 | |

| Carbon aerogel | 4 M KOH | 23 | 650 | |

| Researcher Products: (ACZnO/CuO with 20 gsm paper soaked in Na2SO4) | ||||

| AC 6% | 1 M Na2SO4 | 18.56 | 1050 | Authors’ Experimental Result |

| AC10% | 13.35 | |||

| AC15% | 13.156 | |||

| AC20% | 11.27 | |||

| Electrode | Electrolyte | Power Density (kW/kg) | Energy Density (Wh/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published Product [Porous Carbon (PC), Surface Area (SA)] | ||||

| PC, SA1496 m2/g | 6 M KOH | 4.2 | 3.3 | [28] |

| Graphene aerogel | 6 M KOH | 7 | 45 | [29] |

| B-doped rGO | 0.5 M | 10 | 5.5 | [30] |

| Graphene nanoribbon | 1 M H2SO4 | 9.7 | 4.10 | [31] |

| Researcher Products [AC, Surface Area (SA)] | ||||

| AC6%, SA1050 m2/g | 1 M Na2SO4 | 18.691 | 5.198 | Authors’ Experimental Result |

| AC10%, SA1050 m2/g | 16.74 | 7.707 | ||

| AC 15%, SA1050 m2/g | 15.85 | 8.85 | ||

| Activated Carbon 20%, 1050 m2/g | 5.863 | 1.623 | ||

| Composite | Voc(V) | Isc (A/m2) | Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC-ZnO/CuO (6%AC ZnO/CuO) | 0.779 | 220.59 | 5.71 | Authors’ result |

| CuO/ZnO | 0.63 | 180 | 4.48 | [32] |

| SnS/ZnO | 0.12 | 0.4 | 0.003 | |

| CdS/SnS | 0.26 | 96 | 1.3 |

| Substrate | Reaction Type | g H2 Per Mole of Substrate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water (H2O) | Electrolysis | 2 g H2/18 g H2O ≈ 0.111 g/g | High energy input, high yield per mole |

| POME (organics) | Microbial electrolysis / fermentation | ~0.0721 g H2 per g carbohydrate | Lower yield, uses waste organics, lower energy input |

| Test No. | Volume of Waste Water (mL) | Durations (mins) | Observation (Bubbles Formation) | Hydrogen Test Results Status | Hydrogen Yield (g/L) Using Different Power Mode Supplying 1 L of POME for Each 30 s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 V DC Power | 12 V Solar Organic EDLOSC | ||||||

| Without ZnO/PVA Thin Film | With ZnO/PVA Thin Film | ||||||

| 1 | 25 | 50 | Very dense in short time | Positive (louder) | 280 | 280 | 280 |

| 2 | 50 | 50 | Very dense but decreased over time | Positive (loudest) | 620 | 600 | 650 |

| 3 | 100 | 50 | Very dense and continuous over time | Positive (extremely high and scary) | 620 | 600 | 710 |

| Input Parameter | Output Parameter | |

|---|---|---|

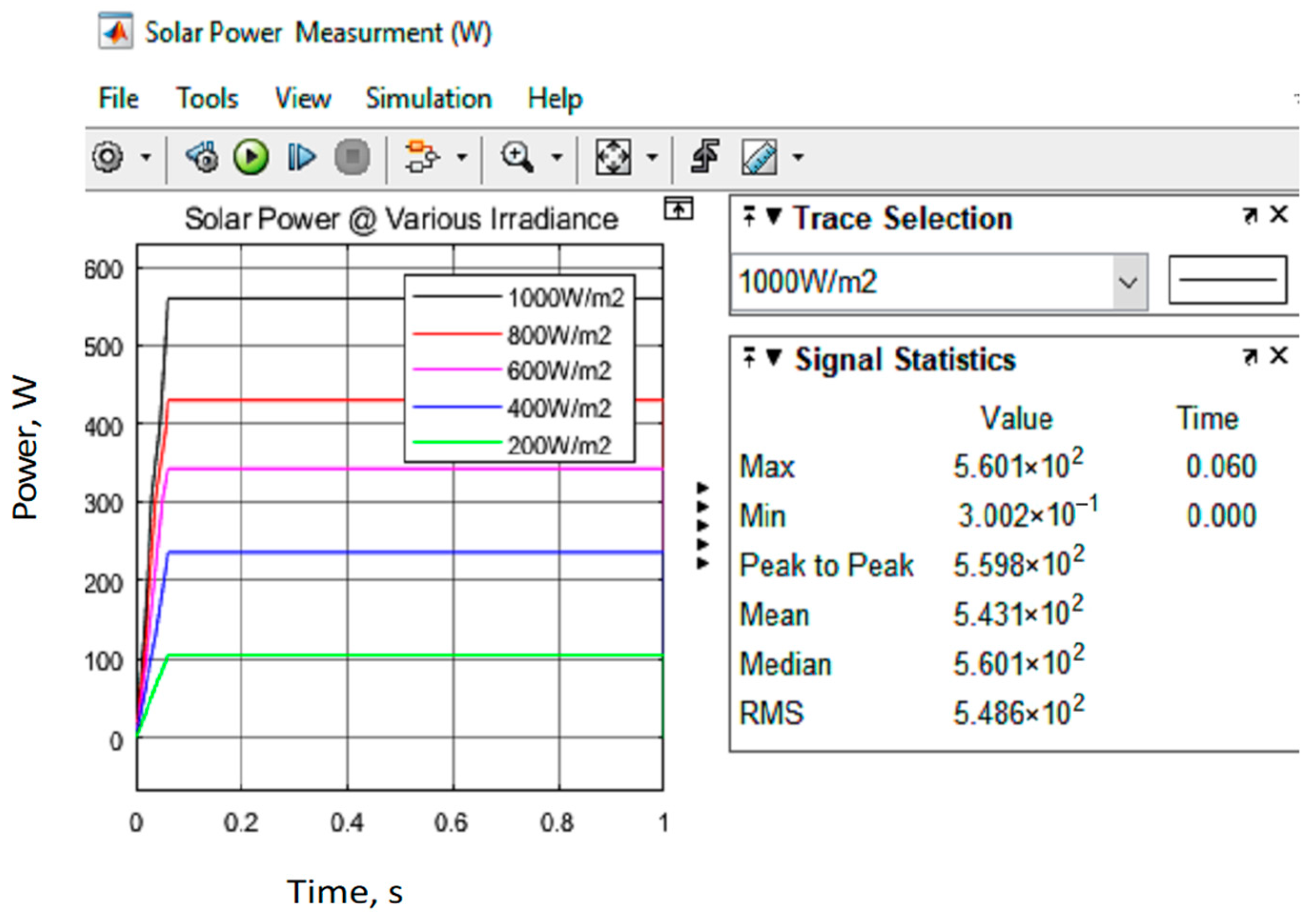

| Temperature (°C) | Irradiance (W/m2) | Psolar (W) |

| 25 | 1000 | 957.1 |

| 25 | 800 | 729.1 |

| 25 | 600 | 584.1 |

| 25 | 400 | 388.4 |

| 25 | 200 | 180.8 |

| Input Parameter | Output Parameter | Time to Deliver Power to the Electrolyzer (Hour) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Irradiance (W/m2) | Psolar (W) | Required Power of Electrolyzer (W) | |

| 25 | 1000 | 957.1 | 120 | 8.0 |

| 25 | 800 | 729.1 | 6.1 | |

| 25 | 600 | 584.1 | 5.0 | |

| 25 | 400 | 388.4 | 3.2 | |

| 25 | 200 | 180.8 | 1.5 | |

| Waste Type | Technology | Pretreatment | Temperature (°C) | Hydrogen Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize straw | Reactor (Batch) | 5% HCl at 118 C | 30 | 4.62 mol/mol | [39] |

| Corn stalk pith | Enzyme cellulase | 30 | 2.6 mol/mol | [40] | |

| Brewery wastewater | Sterilized at 120 C for 20 min | 30 | 0.22 L/L | [10] | |

| Sugar cane bagasse | - | 34 | 0.75 L/L waste | [41] | |

| Sugar beet molasses | - | 30 | 12.7 mol/mol | [11] | |

| Apple waste | Crushed and | 30.5 | 112 mL/L | [13] | |

| screened | |||||

| POME waste | Electrolyzer (using EDLOSC solar-dependent capacitor power control with AI system) | No pretreatment | 35 | 600–710 mL/L | Authors’ findings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahman Md, A.; Qatu, M.; Labib, H.; Afroz, R.; Ghatus, M.; Ihsan, S. An AI-Driven TiO2-NiFeC-PEM Microbial Electrolyzer for In Situ Hydrogen Generation from POME Using a ZnO/PVA-EDLOSC Nanocomposite Photovoltaic Panel. Nanoenergy Adv. 2025, 5, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040018

Rahman Md A, Qatu M, Labib H, Afroz R, Ghatus M, Ihsan S. An AI-Driven TiO2-NiFeC-PEM Microbial Electrolyzer for In Situ Hydrogen Generation from POME Using a ZnO/PVA-EDLOSC Nanocomposite Photovoltaic Panel. Nanoenergy Advances. 2025; 5(4):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040018

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman Md, Ataur, Mohamad Qatu, Hassan Labib, Rafia Afroz, Mehdi Ghatus, and Sany Ihsan. 2025. "An AI-Driven TiO2-NiFeC-PEM Microbial Electrolyzer for In Situ Hydrogen Generation from POME Using a ZnO/PVA-EDLOSC Nanocomposite Photovoltaic Panel" Nanoenergy Advances 5, no. 4: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040018

APA StyleRahman Md, A., Qatu, M., Labib, H., Afroz, R., Ghatus, M., & Ihsan, S. (2025). An AI-Driven TiO2-NiFeC-PEM Microbial Electrolyzer for In Situ Hydrogen Generation from POME Using a ZnO/PVA-EDLOSC Nanocomposite Photovoltaic Panel. Nanoenergy Advances, 5(4), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040018