The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

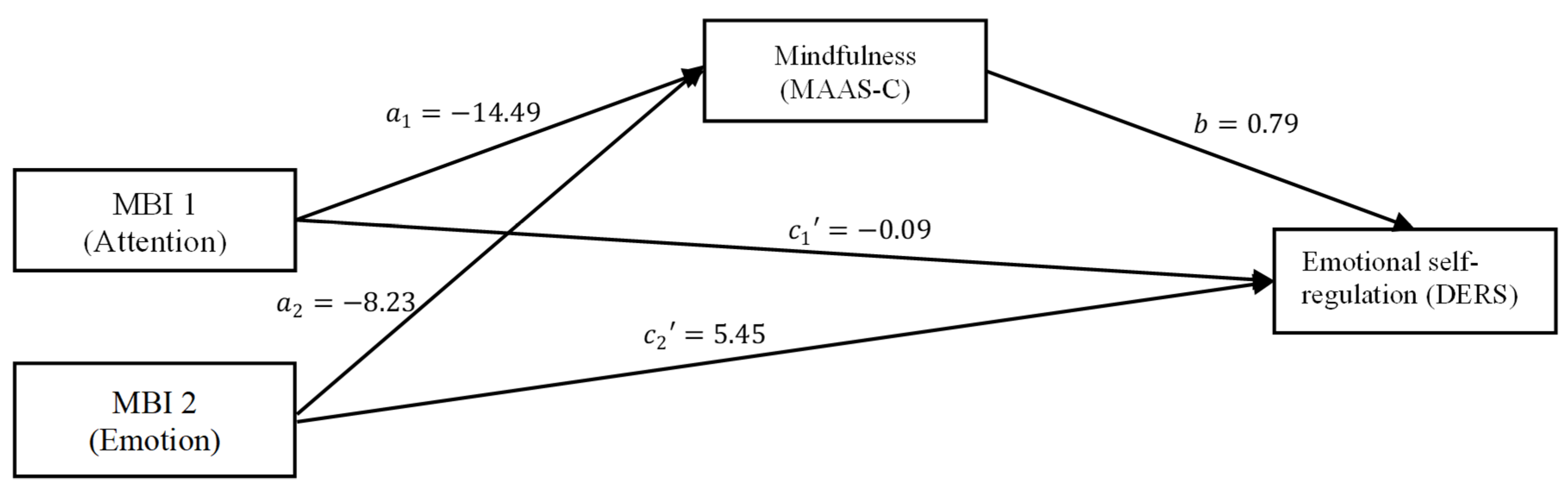

3.1. Emotional Self-Regulation

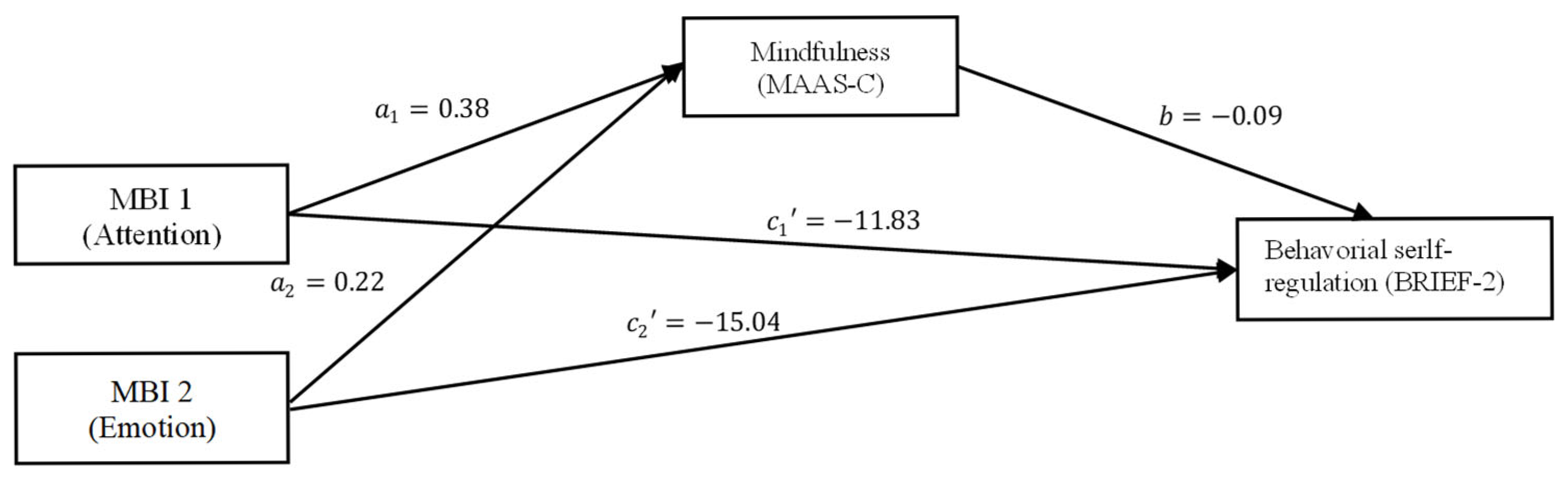

3.2. Behavioral Self-Regulation

3.3. Attentional Self-Regulation—Response Time to Incongruent Stimuli

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaunhoven, R.J.; Dorjee, D. How does mindfulness modulate self-regulation in pre-adolescent children? An integrative neurocognitive review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M.M.; Geldhof, G.J.; Cameron, C.E.; Wanless, S.B. Development and self-regulation. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, M.M.; Geldhof, G.J.; Cameron, C.E.; Wanless, S.B. Self-regulation. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck, B.B. Pruning recurrent neural networks replicates adolescent changes in working memory and reinforcement learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, M.R.; Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. In Measurement of Executive Function in Early Childhood; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2016; pp. 573–594. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Movalli, M.; Maffei, C. Difficulties with emotion regulation, mindfulness, and substance use disorder severity: The mediating role of self-regulation of attention and acceptance attitudes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2018, 45, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Ogliari, A.; Movalli, M.; Maffei, C. Persistent Deficits in Self-Regulation as a Mediator between Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Substance Use Disorders. Subst. Use Misuse 2022, 57, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anto, S.P.; Jayan, C. Self-esteem and emotion regulation as determinants of mental health of youth. SIS J. Proj. Psychol. Ment. Health 2016, 23, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Felver, J.C.; Tipsord, J.M.; Morris, M.J.; Racer, K.H.; Dishion, T.J. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Children’s Attention Regulation. J. Atten. Disord. 2014, 21, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Hölzel, B.K.; Posner, M.I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Vine, V.; Curtiss, J.; Klemanski, D.H. Observing nonreactively: A conditional process model linking mindfulness facets, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 165, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.; Herwig, U.; Opialla, S.; Hittmeyer, A.; Jäncke, L.; Rufer, M.; Holtforth, M.G.; Brühl, A.B. Mindfulness and emotion regulation—An fMRI study. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 9, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Oberle, E.; Lawlor, M.S.; Abbott, D.; Thomson, K.; Oberlander, T.F.; Diamond, A. Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Smith, V.; Zaidman-Zait, A.; Hertzman, C. Promoting Children’s Prosocial Behaviors in School: Impact of the “Roots of Empathy” Program on the Social and Emotional Competence of School-Aged Children. Sch. Ment. Health 2011, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, H.; Buchheld, N.; Buttenmüller, V.; Kleinknecht, N.; Schmidt, S. Measuring mindfulness—The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Lazar, S.W.; Gard, T.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Vago, D.R.; Ott, U. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Oyanadel, C.; Betancourt, I.; Worrell, F.C.; Peñate, W. Effects of Two Online Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Early Adolescents for Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombas, A.S.; Jiménez, T.I.; Arguís-Rey, R.; Hernández-Paniello, S.; Valdivia-Salas, S.; Martín-Albo, J. Impact of the Happy Classrooms Programme on Psychological Well-being, School Aggression, and Classroom Climate. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1642–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Gucht, K.; Takano, K.; Raes, F.; Kuppens, P. Processes of change in a school-based mindfulness programme: Cognitive reactivity and self-coldness as mediators. Cogn. Emot. 2018, 32, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, L.A.; Haden, S.C.; Hagins, M.; Papouchis, N.; Ramirez, P.M. Yoga and Emotion Regulation in High School Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 794928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Perazzini, M.; Bontempo, D.; Perilli, E.; D’aMico, S. Narcissism and Problematic Social Media Use: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Fear of Missing out and Trait Mindfulness in Youth. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2024, 41, 8554–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, M.S.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Gadermann, A.M.; Zumbo, B.D. A Validation Study of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale Adapted for Children. Mindfulness 2013, 5, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; West, A.M.; Loverich, T.M.; Biegel, G.M. Assessing adolescent mindfulness: Validation of an Adapted Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 23, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, E.; Sampedro, A.; Orue, I. Propiedades Psicométricas de la Versión Española de la” Escala de Atención y Conciencia Plena Para Adolescentes”(Mindful Attention Awareness Scale-Adolescents)(Maas-a). Psicol. Conduct. 2014, 22, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Gratz, K.L.; Koot, H.M. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Adolescents Using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Assessment 2009, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Trabucco, C.; Urzúa, M.A.; Garrido, L.; Leiva, J. Validez y Confiabilidad de la Versión Adaptada al Español de la Escala de Dificultades de Regulación Emocional (DERS-E) en Población Chilena. Ter. Psicológica 2014, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanadel, C.; Núñez, Y.; González-Loyola, M.; Jofré, I.; Peñate, W. Association of Emotion Regulation and Dispositional Mindfulness in an Adolescent Sample: The Mediational Role of Time Perspective. Children 2022, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Guy, S.C.; Kenworthy, L. TEST REVIEW Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Child Neuropsychol. 2000, 6, 235–238, Erratum in Child Neuropsychol. 2016, 22, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Retzlaff, P.D.; Espy, K.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a Clinical Sample. Child Neuropsychol. 2002, 8, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salas, C.P.; Ramos, C.; Oliva, K.; Ortega, A. Bifactor Modeling of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a Chilean Sample. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2016, 122, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, B.A.; Eriksen, C.W. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Percept. Psychophys. 1974, 16, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K.; Sheese, B.E.; Voelker, P. Developing Attention: Behavioral and Brain Mechanisms. Adv. Neurosci. 2014, 2014, 405094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Anderson, J.E.; Richler, J.; Wallner-Allen, K.; Beaumont, J.L.; Conway, K.P.; Gershon, R.; Weintraub, S. NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (CB): Validation of Executive Function Measures in Adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2014, 20, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöstmann, N.M.; Aichert, D.S.; Costa, A.; Rubia, K.; Möller, H.-J.; Ettinger, U. Reliability and plasticity of response inhibition and interference control. Brain Cogn. 2013, 81, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Hirose, K.; Keele, L.; Imai, K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 59, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Jia, F. A New Procedure to Test Mediation With Missing Data Through Nonparametric Bootstrapping and Multiple Imputation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2013, 48, 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, K.; Keele, L.; Tingley, D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, L.; Meloni, S.; Lanfredi, M.; Rossi, R. School-based interventions to improve emotional regulation skills in adolescent students: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Seiden, D. Effects of a Brief Mindfulness Curriculum on Self-reported Executive Functioning and Emotion Regulation in Hong Kong Adolescents. Mindfulness 2019, 11, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, F.; Henderson, S.L. Does mindfulness benefit adolescents’ academic adaptation? The mediating roles of autonomous and controlled motivation. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 24239–24251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Du, N.; Shi, S.; Lu, S. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Peer Relationships of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Mendelson, T.; Lee-Winn, A.; Dyer, N.L.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials Testing the Effects of Yoga with Youth. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1336–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, S.C.; Vyas, S.S.; Monson, C.M. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Low-Income Schools. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1316–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraska, J.M. The last stage of development: The restructuring and plasticity of the cortex during adolescence especially at puberty. Dev. Psychobiol. 2024, 66, e22468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İçer, S. Functional connectivity differences in brain networks from childhood to youth. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2020, 30, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, L.; Pine, D.S.; Fox, N.A.; Averbeck, B.B. Changes in Behavior and Neural Dynamics across Adolescent Development. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 8723–8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, N.; Ball, G.; Seal, M.L.; Mundy, L.; Whittle, S.; Silk, T. The development of structural covariance networks during the transition from childhood to adolescence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, L.-M.; de Diaz, N.N.; Sherwood, A.; Waters, A.; Farrell, L. Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2019, 44, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Oyanadel, C.; Sáez-Delgado, F.; Andaur, A.; Peñate, W. Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Child-Adolescent Population: A Developmental Perspective. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 1220–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickerell, L.E.; Pennington, K.; Cartledge, C.; Miller, K.A.; Curtis, F. The Effectiveness of School-Based Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioural Programmes to Improve Emotional Regulation in 7–12-Year-Olds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, Q. How could mindfulness-based intervention reduce aggression in adolescent? Mindfulness, emotion dysregulation and self-control as mediators. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 4483–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, B.; Karanam, A.; Pelakh, A.; Goldberg, S.B. Adolescents do not benefit from universal school-based mindfulness interventions: A reanalysis of Dunning et al. (2022). Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1384531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.; Tudor, K.; Radley, L.; Dalrymple, N.; Funk, J.; Vainre, M.; Ford, T.; Montero-Marin, J.; Kuyken, W.; Dalgleish, T. Do mindfulness-based programmes improve the cognitive skills, behaviour and mental health of children and adolescents? An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twisk, J.; De Boer, M.; De Vente, W.; Heymans, M. Multiple imputation of missing values was not necessary before performing a longitudinal mixed-model analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, E. Deconstructing Developmental Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fourneret, P.; des Portes, V. Developmental approach of executive functions: From infancy to adolescence. Arch. Pediatr. Organe Off. Soc. Fr. Pediatr. 2017, 24, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Easterbrooks, M.; Mistry, J. Developmental science across the life span: An introduction. In Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.H. Theories of Developmental Psychology; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Veer, I.M.; Luyten, H.; Mulder, H.; van Tuijl, C.; Sleegers, P.J. Selective attention relates to the development of executive functions in 2,5- to 3-year-olds: A longitudinal study. Early Child. Res. Q. 2017, 41, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | n Girls | n Boys | Total n Post-MBI | Girls Age (DS) | Boys Age (DS) | Mean Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | 14 | 10 | 24 | 9.93 (1.33) | 9.90 (0.88) | 9.91 |

| Emotion | 13 | 12 | 24 | 10.00 (0.60) | 9.50 (0.80) | 9.75 |

| Control | 12 | 9 | 22 | 9.08 (1.04) | 9.11 (1.05) | 9.09 |

| Total | 39 | 31 | 70 | 9.66 (1.10) | 9.51 (0.92) | 9.60 |

| Variable | Pre-Intervention Assessment | Post-Intervention Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion MBI (SD) | Attention MBI (SD) | Control Group (SD) | Emotion MBI (SD) | Attention MBI (SD) | Control Group (SD) | |

| Mindfulness (MAAS-C) | 37.84 (10.07) | 36.75 (11.03) | 39.14 (5.39) | 33.40 (10.51) | 26.24 (5.39) | 41.05 (11.81) |

| Emotional self-regulation (DERS) | 70.48 (14.94) | 65.33 (14.39) | 60.75 (12.81) | 64.35 (14.58) | 52.90 (8.68) | 64.47 (17.06) |

| Behavioral self-regulation (BRIEF-2) | 112.84 (18.54) | 114.58 (23.03) | 118.14 (21.40) | 105.40 (16.39) | 109.57 (21.04) | 121.55 (17.73) |

| Response time to incongruent stimuli (Flanker task) | 900.65 (134.56) | 932.14 (153.58) | 946.33 (163.95) | 803.75 (103.44) | 748.95 (123.33) | 921.78 (147.88) |

| Error Rate for congruent stimuli (Flanker task) | 21.59 (17.66) | 22.65 (15.85) | 19.03 (15.45) | 14.52 (12.63) | 13.03 (10.10) | 19.09 (16.50) |

| Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACME | −11.47 | −20.80 | −4.22 | 0.0004 *** |

| ADE | −0.09 | −9.55 | 9.93 | 0.9892 |

| Total Effect (β) | −11.56 | −20.68 | −3.10 | 0.0072 ** |

| Prop. Mediated | 0.99 | 0.37 | 3.07 | 0.0076 ** |

| Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACME | −0.03 | −4.05 | 5.02 | 0.9660 |

| ADE | −11.83 | −24.06 | −0.42 | 0.0428 * |

| Total Effect (β) | −11.86 | −24.21 | −0.11 | 0.0480 * |

| Prop. Mediated | 0.002 | 0.97 | 0.53 | 0.9452 |

| Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACME | −7.72 | −49.72 | 40.34 | 0.6932 |

| ADE | −141.99 | −256.26 | −42.42 | 0.0052 ** |

| Total Effect (β) | −149.72 | −237.68 | −65.92 | 0.0004 *** |

| Prop. Mediated | 0.05 | −0.24 | 0.46 | 0.6936 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porter, B.; Oyanadel, C.; Betancourt-Peters, I.; Peñate, W. The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Adolescents 2025, 5, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040072

Porter B, Oyanadel C, Betancourt-Peters I, Peñate W. The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040072

Chicago/Turabian StylePorter, Bárbara, Cristian Oyanadel, Ignacio Betancourt-Peters, and Wenceslao Peñate. 2025. "The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040072

APA StylePorter, B., Oyanadel, C., Betancourt-Peters, I., & Peñate, W. (2025). The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in Attentional, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Regulation During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Adolescents, 5(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040072