Abstract

(1) Background: While Hong Kong is renowned for being a multicultural city, its South and Southeast Asian population has experienced disadvantages in various aspects of life, particularly career development. This study adopts the Systems Theory Framework (STF) to investigate the school-to-work transition of Pakistani, Nepalese, Filipino, and Indian youths in the Hong Kong Chinese context. (2) Methods: A qualitative approach using individual and focus group interviews was employed to uncover and critically examine educational and career aspirations and contextual factors in the transition pathways of educational and career advancement experienced by these ethnic groups. (3) Results: Findings show that career aspirations among South and Southeast Asian youths undergoing the school-to-work transition are comparatively lower than those of their counterparts who remain in secondary education. This disparity is attributed to a range of contextual factors, particularly shortcomings in education policy and limited cultural competence within Hong Kong Chinese society, both of which contribute to the erosion of occupational outlook among these underrepresented groups. (4) Conclusions: This study demonstrates the critical impact of contextual factors on the ethnic inequality of school-to-work transition, which are more overwhelming than can be overcome by personal and family efforts. If these issues are not addressed, achieving racial equality and equal opportunity in school-to-work transition will remain a persistent challenge.

1. Introduction

The school-to-work transition has become an important topic in youth studies in the past two decades, especially in the context of globalization and risk society [1,2,3]. The problems of transition experienced by young people have been thoroughly examined in different countries, including Hong Kong [4,5,6], which has been acclaimed as a world city, lauded for its openness to the outside world and its diverse culture. This paper critically discusses the struggles experienced by and contextual barriers confronting South and Southeast Asian youths in their pathways of school-to-work transition. We use the term ‘South and Southeast Asian youths’ to specifically refer to young people who are ethnic Pakistani, Nepalese, Filipino, and Indian individuals. These ethnic groups constitute the largest non-Chinese ethnic population in Hong Kong. This paper is based primarily on the qualitative aspects of a larger research project which seeks to understand the obstacles faced by South and Southeast Asian youths in their school-to-work transition and their struggles in overcoming these barriers.

Similar to other societies with liberal welfare regime, in the social policy context of Hong Kong, poverty and vulnerabilities are often understood as personal and family incompetence and thus individual responsibilities [7,8,9]. We found that the disadvantages experienced by South and Southeast Asian youths in the school-to-work transition are heavily socially embedded in the Hong Kong Chinese context, and they are more overwhelming than can be overcome by personal and family efforts. We argue that these contextual disadvantages experienced in the school-to-work transition are an ongoing process that will continue unabated without social intervention, and the result will be social segregation of ethnically diverse groups from society.

In this paper, we begin by highlighting the demographic and social backdrop of South and Southeast Asian people in Hong Kong with a specific focus on the disadvantages confronting them, followed by the discussion of theories of school-to-work transition, particularly the Systems Theory Framework (STF), which will be adopted for analysis in this study. The findings will then be discussed in light of the STF, with a critical examination of the contextual barriers experienced by these youth groups and the need to tackle structural issues in order to bring about genuine racial equality and equal opportunity in all young people with ethnically diverse backgrounds.

1.1. Theories of School-to-Work Transition

Career development theories have evolved over time. Early theories, such as Parson’s Theory of Personality [10], focused on the characteristics of individuals and workplaces, emphasizing the content of career choice. The later-developed person–environment fit theories explored the interaction between individuals and their work contexts. For example, Holland’s [11] Theory of Vocational Personalities in Work Environment focused on individual occupational choice and the interactive process between the individual and the work environment. Subsequent developmental theories, represented by Super’s [12] Self-concept Theory of Career Development, emphasized the sequential and developmental nature of career growth. By the 1980s and 1990s, theorists began integrating both content and process, recognizing the role of cognition and the dynamic nature of career paths. One example is Social Cognitive Career Theory, which emphasizes the core roles of three variables, namely self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and personal goals, in vocational interests, choices, career success, and satisfaction [13]. In recent years, contemporary approaches such as Savickas’s [14] career construction theory have incorporated constructivist and social constructionist influences on the roles of individuals and environments in career development.

The Systems Theory Framework (STF), first introduced by McMahon & Patton [15], provides an integrative and flexible approach to acknowledge cultural contexts, personal development, and the evolving macroenvironment. The STF is an attempt to present a comprehensive framework of a series of interconnecting systems of influence on career development. At the heart of the framework is the individual system which refers to a series of personal influences such as gender, age, abilities, and ethnicity. The social system refers to the other people systems with which the individual interacts, for example, family, educational institutions, and peers. The environmental–societal system refers to the broader system of the society and the environment composed of a series of subsystems such as geographic location, government policy, and the values, beliefs, and attitudes of the public [16].

The STF aims to identify two broad components of career development, namely content and process. Content is defined as the intrinsic (individual characteristics) and contextual (the environment) influences on career development. Process refers to the recursive interaction of influences within the individual and within the context, and between the individual and the context, and it changes over time [16].

The influence of content on one’s career development varies across stages of school-to-work transition. Patton & McMahon [16] argue that at the stage where an individual leaves school, age, individual ability, family, socioeconomic status, and the employment market are particularly important to career development. Using the STF as a guiding framework for analysis of the data derived from qualitative interviews, Tsui et al. [17] also found that a majority of senior secondary school students in Hong Kong aspired to pursue post-secondary education and that their educational and career aspirations were influenced by their academic performance and personal interests (individual system), their families (social system), and job prospects (environmental–societal system).

The STF is not a theory of career development. Thus, it does not offer a detailed account of particular phenomena and can be perceived as general and abstract. Rather, the STF takes a pluralistic view of career theories which provide an explanation of specific elements of career development that can be utilized in theory and practice. On this basis, practitioners can focus on individuals and their relevant systems and processes. Therefore, the practitioner’s interventions are more likely to be tailored to the needs of the individual or specific group rather than the theoretical preferences of the practitioner [16]. For example, a study of Australian undergraduate brass musicians shows that the STF can serve as an effective framework for discussing the diverse influences on young people’s career aspirations [18]. An integrated literature review also demonstrates that the STF can facilitate contextualization of various factors affecting career development [19]. In light of this, this study adopts the STF to investigate the school-to-work transition of South and Southeast Asian youths in the Hong Kong Chinese context.

1.2. Population of South and Southeast Asian Individuals in Hong Kong

In the academic sector and some Western societies, the term ‘minority’ can carry pejorative connotations, as it is often associated with inferiority, marginalization, or deficiency relative to the majority group, for example [20,21]. However, the term ‘ethnic minority’ (EM) remains widely used by both the Hong Kong government and broader Hong Kong society. EMs refer to people who reported themselves being of non-Chinese ethnicity in the population census [22,23]. This group is highly diverse, ranging from white people from rich Western economies, to East Asian individuals from Japan and South Korea, to relatively poorer South Asian individuals from Pakistan, Nepal, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, and the like. According to the most recent census data, in 2021 a total of 619,568 people of ethnically diverse backgrounds are living in Hong Kong, comprising 8.4% of the total population. After excluding foreign domestic helpers who are not the target of this study, there were 301,344 ethnically diverse people, making up 4.1% of the whole population. Among them, 57.1% were South and Southeast Asian, and the remainder were white people and other ethnic groups. Of those non-Chinese Asian individuals, Indian and Nepalese individuals constituted the largest shares (22.4% and 17.2%, respectively) of the population, followed by Filipino and Pakistani individuals, who represented 15.2% and 14.1%, respectively [23,24].

1.3. The Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Despite the fact that the overall labour participation rates of South and Southeast Asian individuals are on par with those of the overall population, Pakistani, Nepalese and Filipino individuals usually hold low-skilled and low-paying jobs. Census data from 2021 shows that 28.8% of Pakistani and 24.5% of Nepalese individuals worked in elementary occupations, more than double the proportion of the overall population (10.0%) [23]. In addition, far fewer South and Southeast Asian individuals occupied managerial, administrative, and professional posts compared to the overall population, with the exception of Indian individuals who, for historical and family reasons, were able to engage in those more stable and high-paying jobs [25]. As far as income is concerned (again with the exception of Indian individuals), Pakistani, Nepalese and Filipino individuals all have a median monthly income that is much lower than that of the overall working population. For instance, the median income of Pakistani individuals was HKD 15,000 (approximately USD 1923), representing only 77% of the median income of the overall Hong Kong population in 2021 (HKD 19,500/USD 2500). The median incomes of Nepalese and Filipino individuals were HKD 17,000 (USD 2179) and HKD 16,500 (USD 2115), respectively, representing around 85% of the overall median income. Among Indian individuals, who appear to be doing relatively well in employment, the median income of Indian women (HKD 20,000/USD 2564) was about 57% that of their male counterparts [23]. The low incomes of Pakistani, Nepalese and Filipino individuals indicate their social disadvantages and the marginalization of the labour market. The ability of South and Southeast Asian individuals to select an occupation appears not to be as equal and free in Hong Kong.

1.4. The Educational Disadvantage

Over the years, more people of non-Chinese ethnic origin have been able to achieve higher education in Hong Kong. In the academic year of 2011/12, one hundred and forty-five ethnically diverse young people were admitted to government-funded university degree programmes versus 253 in the 2016/17 academic year, representing an increase of 74.5% over five years. The increase in ethnically diverse youths in self-financed degree programmes is even more remarkable—rising from 23 to 529 between 2011 and 2016, a 22-fold increase [26]. However, the increase in higher education participation does not paint a rosy picture of education equality. For instance, government census statistics show that in 2021, the school attendance rate of ethnically diverse groups aged between 18 and 24 was only 50%, which was 5.8% below the age-specific group of the entire population [23]. A recent study also showed that although some South Asian students completed post-secondary education in Hong Kong, they encountered a series of barriers such as marginalization and few opportunities as compared to their Chinese counterparts in the employment market [27].

Moreover, there are structural barriers which impede South and Southeast Asians from equal educational pursuit. With respect to the learning and teaching of the Chinese language, the lack of supportive policies and learning-appropriate curricula are, amongst other factors, important barriers to educational advancement [28]. Due to the lack of a supportive Chinese language environment within families and ethnic minority communities, many ethnically diverse students encounter difficulties in acquiring Chinese as a second language. As a result, they often struggle to cope with the Chinese language curriculum of the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE), which is designed for ethnic Chinese students. To facilitate their progression into further studies or employment, the Hong Kong government allows non-Chinese-speaking students to pursue alternative Chinese language qualifications, including the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE), General Certificate of Education (GCE), and Applied Learning Chinese (ApL(C)) [29]. While these alternative qualifications are accepted by all higher education institutions, the current curriculum offerings for ethnic minorities do not adequately address the practical language demands of daily vocational tasks and workplace communication.

Law and Lee [25] argue that Hong Kong has a legacy of white supremacy established in the colonial era, where the use of English was not only necessary but was also a class symbol. People with lower education levels and those who occupied low-income and low-skill jobs relied on colloquial Chinese for their job survival. While the class-based embeddedness of language use may have been taken for granted as a natural matter of ordinary life, it has had long-lasting negative impacts on the school–work transition of ethnically diverse youths. One typical example is that the majority of South and Southeast Asian individuals, especially those from Pakistan, Nepal, and the Philippines, seek elementary and non-skilled occupations, which usually require knowledge of colloquial Chinese. This problem is both a cause and consequence of labour market marginalization, and it makes job seeking much more difficult [26].

1.5. Limited Cultural Competence

Limited cultural competence within Hong Kong Chinese society also contributes significantly to the disadvantaged circumstances faced by ethnically diverse groups. Previous studies commonly suggested that ethnically diverse groups are not well accepted by the majority population, who are generally ethnic Chinese [30]; that child poverty among South and Southeast Asian populations are relatively more prevalent [31]; and that many of them suffer from racial inequalities in education [32]. In this regard, Law and Lee [33] rightly argued that discriminations against ethnically diverse groups are deeply embedded in both the culture and the socio-political structure of Hong Kong. Faced with low receptivity by the ‘host environment’, disadvantages may sometimes be accepted as natural by all parties, including South and Southeast Asian individuals themselves.

In our subsequent discussions, we reveal the disadvantages and obstacles in the transitional pathway of education and career advancement of South and Southeast Asian youths. We argue that social segregation and social exclusion are both a cause and consequence of these disadvantages, which urgently need to be addressed.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative approach, which has the merit of exploring beliefs, attitudes, and viewpoints, to investigate the school-to-work transition of ethnically diverse groups. Semi-structured individual and focus group interviews were used to tap into their views on their experiences with transitioning to careers. The aim of qualitative research is to seek the subjective truth, meanings, and experiences of the participants in the social, political, and cultural contexts in which they live [34,35,36]. This is especially important for studies conducted in multicultural settings, as participants’ experiences and the meanings they assign to those experiences can easily be buried under mainstream cultural interpretations.

2.1. Sampling and Participants

As Baan et al. argue, the school-to-work transition is a continuous process rather than a single event [37]. To better explore the pre-existing factors affecting transition and the changes in aspiration over time, the sample should include youths undergoing a transition from senior secondary education to entry into work. Thus, purposive sampling was used to recruit South and Southeast Asian youths, including Pakistani, Nepalese, Filipino, and Indian individuals who were at different stages of transition paths, for the study. Four categories of youths were recruited: (1) senior secondary students (secondary 4 to 6, S4–S6) who were preparing for post-secondary planning, (2) students who made the transition to post-secondary education, (3) working youths, and (4) youths who were unsuccessful at different stages of different pathways.

The participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, in collaboration with local non-government organizations and secondary schools. While some of them expressed a preference for individual interviews, since this option provides flexibility in scheduling, others felt more comfortable talking in a group setting. A total of 53 South and Southeast Asian youths in different transition paths were recruited for the study; 26 took part in individual interviews, whilst 27 participated in focus group interviews. The characteristics of the South and Southeast Asian participants are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. In order to cross-validate the findings related to schools and the employment market, individual interviews were also conducted with eight secondary school teachers and ten employers from companies of different industries and different sizes. The details of the teachers and employers are listed in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in education. (a) S4–S6 students in individual interviews (n = 16); (b) post-secondary students in focus groups (n = 20).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants regarding employment status. (a) From S.6 to work (n = 6); (b) from post-secondary education to work (n = 11).

Table 3.

Characteristics of secondary school teachers in individual interviews (n = 8).

Table 4.

Characteristics of employers in individual interviews (n = 10).

2.2. Individual and Focus Group Interviews

Human subject ethical approval for conducting this study was obtained from the university of the authors. Prior to each individual and focus group interview, the purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants, with an emphasis on voluntary participation and confidentiality. They were informed of their right to decline or discontinue the interviews at any time. All participants provided informed consent. The interview guide for both individual and focus group interviews primarily covered (1) the overall experiences in school-to-work transitions of ethnically diverse youths and (2) observations on the social barriers encountered by ethnically diverse youths in their transitions. All interviews with ethnically diverse youths were conducted in the English language, while those with teachers and employers were conducted in Chinese. Each individual interview lasted about one hour, whilst focus group interviews were about two hours in length. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for analysis without revealing details of the participants.

2.3. Thematic Analysis

This study used thematic analysis to analyze the data [38,39] based on the STF. This technique searches for themes or patterns and is useful for identifying the key issues of specific individuals or groups in descriptive studies. An analytical search procedure was developed to identity the content and process embedded in the individual, social, and environmental–societal systems of the STF. The researchers first achieved familiarity with the data by reading the transcripts of each individual and focus group interview several times to outline the initial findings. Then, the unique features of the data were noted, and preliminary codes were generated. The researchers also discussed the codes, defined the relationships between the codes, and marked relevant text from each individual interview. A codebook was used to document potential codes/themes for the theoretical and reflective statements, maintain the audit trails, demonstrate procedural logic, and provide transparency [39,40]. A data mining method was then used to condense the codes into meta-codes (clusters). Coding divergence and convergence was also addressed [41,42]. The codes were applied, and subsequently, a search was carried out for themes and subthemes. The specifics of each subtheme were then analyzed and refined into the main themes [40]. A semantic approach was used to match the themes to the basic codes. The researchers also progressed beyond the semantic contents and used a latent approach, which examined the underlying assumptions and interdependent concepts in the interviews. Throughout the process of data analysis, there were regular discussions in the research team about identifying and refining themes and ensuring that researchers were not influenced by pre-assumptions in interpretations.

3. Results

This study found no notable disparities across ethnic or gender groups, except for the gender roles among Pakistani and India participants, which will be discussed in a later session. Guided by the STF, several themes were identified and organized according to the individual, social, and environmental–societal systems that influence the school-to-work transition of the South and Southeast Asian youths in Hong Kong.

3.1. Individual System

3.1.1. Aspiration

Findings derived from interviews with South and Southeast Asian students, teachers, and employers showed that educational and career aspirations among youths in post-secondary education or those who are employed were comparatively lower than those of their peers still attending secondary school. In other words, secondary students usually demonstrated stronger educational and career aspirations.

For my education, I believe that I can do well… I’ve been told that I was smart… I hope I could do well and get into the university that I want. For career, I want to do well. I hope to do well.[Secondary 6 student, Filipino, female, 10s, individual interview]

If you can work inside the governmental departments, if you can have a high status, Hong Kong can belong to you in the future.[Secondary 4 student, Pakistani, male, 10s, individual interview]

Some girls (female South Asian students) want to become teachers, and some have even thought about becoming doctors… Even local (Chinese) students have hesitation… In fact, the South Asian girls at our school do quite well academically… Maybe that also influences their choices.[Teacher, Chinese, female, 30s, individual interview]

There’s no big difference [between ethnically diverse and ethnic Chinese students] in terms of education and career aspirations.[Teacher, Chinese, male, 30s, individual interview]

In contrast, ethnically diverse youths in post-secondary education and those who are employed often demonstrated lower career aspirations. Even those with post-secondary qualifications frequently remained in elementary jobs for extended periods and expressed pessimism about their career development.

I have one very close friend… We end up going to the same university, then after that we went back to the workforce… My friend, he couldn’t find a job… So he ends up working as a construction worker… Why is that? So my friend ends up what he is doing now more than 6 or 7 years, so he is always in that field.[Employed youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Nepalese, male, 20s, individual interview]

Of course, if you’re a Chinese Hong Konger and you’re in Hong Kong, there’s one ethnic minority person and one Hong Kong (Chinese) person, they’ll definitely hire the (Chinese) Hong Konger. Because they speak Cantonese, right? They do things better and understand the culture. On the other side, the ethnic minorities… There are a lot of things they don’t really know, so they can’t do it. They cannot communicate. That’s it.[Unemployed youth who pursued foundation diploma, Indian, female, 20s, individual interview]

Meanwhile, some employers perceived that the non-Chinese-speaking staff, including locally and non-locally educated ones, generally showed a lower desire to develop their careers.

Hong Kong (Chinese) people might work harder because they want a promotion or want to fight for opportunities. But I find that they (ethnically diverse staff) focus only on completing their duties. “I do this job, I do these tasks,” and they don’t expect anything more. I feel they tend to have that kind of attitude.[Employer 2 from a catering group, individual interview]

It is obvious… They don’t have to desire to get promoted. They are satisfied with the status quo… I feel that compared to the ethnic Chinese staff, they are more satisfied with the status quo.[Employer 8 from a primary school, individual interview]

3.1.2. Inadequate Chinese Language Proficiency

The other important content is the Chinese language. English is one of the two official languages. The mixture of Cantonese and English in everyday spoken communication is therefore widespread. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, in Hong Kong, the use of Cantonese dialect and written Chinese in everyday life and workplace is common. Most South and Southeast Asian youths indicated that inadequate Chinese language proficiency was a factor.

Actually one of the difficulties was the language… I tried to apply for another job as well., for like, in other companies, in IT, and as a customer service officer in other companies. But because of the Chinese languages, totally too difficult to find jobs…[Unemployed youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Pakistani, male, 20s, individual interview]

I don’t know Chinese at all. The school I worked was a local school, so it was really hard for me to communicate with teachers. Sometimes they said something… Whenever they say something, I was like… Staring at them and I don’t say anything. And then they will say “Aiya. Do this!” So they were like quit stayed with me coz it’s a norm for me understanding Chinese so that is the bad part that I don’t like about my job.[Unemployed youth without post-secondary education, Pakistani, female, 20s, individual interview]

Some employers from large-sized organizations with specific missions are able to accommodate ethnically diverse staff with limited Chinese proficiency. For instance, Employer 10 from a social service agency hires ethnically diverse youths to develop services tailored to their ethnic communities. However, most employers, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that focus on the local market, considered Chinese language proficiency, including reading and writing, a basic job requirement.

We are a SME. Most of our clients come from Hong Kong. Though the email messages of most clients are in English, we need to prepare content in Chinese sometimes. For example, if you cannot read and write Chinese, it is difficult to make a website in Chinese.[Employer 6 from an information technology company, individual interview]

I’m worried they (ethnically diverse staff) won’t be able to manage the work… You know their (Mainland China customers’) phrasing and wording (in Chinese). Even we might not be able to fully understand it. If we give them (ethnically diverse staff) that kind of material and they find it hard to understand… Then it’s really tough for them… No wonder employers don’t want to hire them. Aside from English, it’s all Chinese. Everything is in Chinese.[Employer 7 from a manufacturing company, individual interview]

3.2. Social System: Family

3.2.1. Financial Hardship

As mentioned above, census data shows that the income of ethnically diverse groups, particularly Pakistani, Nepalese, and Filipino populations, is generally much lower than that of the overall working population [23]. Our findings show how financial hardship frustrates South and Southeast Asian youths in making educational decisions and limits their aspirations for educational advancement beyond secondary school:

We are a family of six. My dad recently got out of his job. My mum is unemployed. She is a housewife… My brother is going to primary [school] and my other brother going to high school… Right now, we thought if we can handle all the expenses… with only one person working in the family and me part-timing. It is not going to be enough for a family of six… So it is definitely something to look out for when you try to study again. Because apart from all the bills you have to pay… You have to pay for your student loan as well. It is monthly… So that is definitely one thing to consider.[Working youth going to pursue a higher diploma, Filipino, female, 20s, focus group]

Some teachers observed that the socioeconomic status of some ethnically diverse families might limit their children’s opportunities and aspirations for further education:

Some of them (ethnically diverse students) are working part-time because their family’s socioeconomic status is relatively low. So sometimes they take on part-time jobs to earn money… They’re already planning to just stay in school for six years, graduate from Secondary 6, and then go to work.[Teacher, Chinese, 40s, female, individual interview]

Also, some are caught in a dilemma where they struggle between needing to work to support their families and pursuing further studies, which they find hard to afford.

I have the chance to study. My supervisor told me that I could study for a teaching assistant or something… related to a social worker. They can support me. But… I think maybe I cannot do it because I have some family issues. Since I am the oldest, so I always like independent, and I will care for my family. I need to pay a rent… And then I don’t want to burden my father for everything. I want to help my father… That’s what in my mind, I just [need to] keep working.[Working youth without post-secondary education, Pakistani, female, 20s, focus group]

Even though the Hong Kong government offers a non-means-tested loan scheme for full-time tertiary students, some youngsters worried about whether they would be able to repay it in the future.

Even if you get a loan, it’s like specifically a recycle of money: you’ll get it, and you have to give it back. But what if you are still going on, the loan keeps adding on and on. And what if you are not able to finish up… Like, for example, you have to stop in the middle, then how are you going to pay up the full loan? So, there can be a setback.[Youth pursuing a diploma, Nepalese, female, 20s, focus group]

Due to financial difficulty, some South and Southeast Asian youths initially wanted to pursue post-secondary education but lost interest in their studies once they entered the labour market in their gap year. The following is one example:

I graduated from F.6 (Secondary 6). But I had a plan in my mind to go for further study, but I would take a gap year. But I found a job… Start working for 1 year, and I wanted to continue working there. Therefore, later, I lost my interest in further study. So I didn’t go for the study.[Working youth without post-secondary education, Pakistani, female, 20s, focus group]

3.2.2. Insufficient Information

Family and parents have a significant role in the transitions of ethnic diverse youths. A Pakistani post-secondary student shares his view:

At the end of the day, the EM youth would listen to their parents. So, whatever schools are telling their kids in school… Okay, there might be a lot of information. Still, then that information would be useless when the discussion (decision) is the parents’ discussion (decision), right? If the student is going to the career talks, study talks, whatever, he would use so much time to listening to a talk. In the end, parents’ decision…[Working youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Indian, male, 20s, individual interview]

However, most South and Southeast Asian youths reported that their family members neither understood the education system in Hong Kong nor had sufficient information about tertiary education. The information poverty led this group of youths to either abandon plans for further education or select subject areas that did not align with their personal interests.

As for my parents… They didn’t study in Hong Kong. My mom was actually born in Hong Kong, but she went back to her hometown when she was around six years old. So she’s not really familiar with Hong Kong’s education system. I might talk to them about how I’m doing in school, but when it comes to giving me advice, they’d just ask things like, ‘Would you consider studying this subject?’ They wouldn’t really be able to give me any practical advice.[Secondary 6 student, Pakistani, female, 10s, individual interview]

I had no idea, no concept… Nobody guides me… If I had pursued social sciences, maybe that was the correct route for me to be a social worker. But uh… Nobody guided me at that time, and my parents were not educated, and then I had no one to ask. My dad was in the hospitality industry, so I thought I would get in the hospitality industry… Nobody guided me. So that’s why I wasted one year [to study hospitality].[Working youth who pursued advanced diploma, Nepalese, female, 20s, individual interview]

3.2.3. Cultural Practice

Concerning family support for ethnically diverse students, the overall mindset of their parents and their gender role perception or practice, in particular, may influence the education and career paths of female youths, especially among some Indian and Pakistani females. They are more likely to be required to get married and/or stop studying after obtaining secondary education.

I would definitely say that culture influence does affect your choice… I mean even if you want to study a lot of times (longer time), you wouldn’t be able to. One of my friends was a really good student in school… Like she used to get a lot of good grades and stuff like that. But then in Form 5, she found out, she’s getting married next year. She wouldn’t be able to get DSE. So, she stopped studying after that… She knew that she couldn’t pursue further. So I think culture does affect as well.[Youth pursuing a bachelor’s degree, Pakistani, female, 20s, individual interview]

3.3. Social System: Schools with Limited Opportunities for Career Exposure

Both teachers and youngsters perceived limited opportunities for South and Southeast Asian students to gain career exposure. However, this issue is attributed to numerous factors. Some ethnically diverse youths reported that career teachers or advisors failed to provide sufficient guidance on career planning in a proper way:

Those guardians, or guidelines, whatever the advisors… is like… A normal guideline (for education and career planning). So, maybe if you put the guideline in your own situation, it won’t work because everyone has different mindset, different goal, different target. So, what that person actually needs is one-to-one conversation with someone professional. The person can say out whatever they think about. And, there’s another problem ethnic minority is they (are) shy to share everything with everyone… If they can be like a private one-to-one, a confidential one, that might help. So, maybe like… There can be like an event or they can have a 15 to 20 min to meet ethnic minority. That might really help…[Working youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Indian, male, 20s, individual interview]

Meanwhile, some teachers reported that language barriers, particularly limited Cantonese proficiency, hinder students’ access to career information and internship opportunities. For example, some career event staff may have limited oral English skills or readiness to communicate in English. A teacher also shared her experience:

Career counselling doesn’t focus on this group of non-Chinese speaking students… Actually, the chances for internship for them are minimal… Some agencies provide internship for students… that is, at the summer of F.4 and F.5 (equivalent to Grades 10 and 11 in the U.S.)… When they learn that the students are non-Chinese speaking, they then refuse to take them… Or because there is no one being able to speak English in working site or place. Still, the Non-Chinese speaking students can only speak English… Then they won’t provide the internship for these students. So this again limits their chances to have the exposure.[Teacher, Chinese, female, 30s, individual interview]

In some cases, students’ limited career exposure may also stem from a lack of awareness about the importance of participating in such activities. One teacher shared his experience to illustrate this point.

If you organize the activities on Saturday, the attendance rate is only 40 to 50%… That means you would worry a lot, even I organize the activities during weekdays. The highest attendance rate is only 80%… 80%!!… Every time going out (for these activities), I usually have to say sorry to the organisations… to tell them how many students who are not able to come… to tell them that the students said they were sick… So many reasons… not attending school on that day, have to take care of siblings after school… So many reasons.[Teacher, Chinese, male, 40s, individual interview]

Considering the perspectives of various stakeholders, it appears that some career-related programmes may not adequately accommodate the needs of ethnically diverse students. Schools may also fall short in enhancing awareness about available opportunities among this group.

3.4. Environmental-Societal System

Education Policy: Shortcomings of Chinese Language Curriculum

Chinese language proficiency varies among ethnically diverse youths from different backgrounds. Some can read, write, and speak Chinese well. However, a majority of students can barely speak Cantonese, while some are neither good at Chinese nor English. Teachers and students generally agreed that the disparity was partly caused by the variations in education pathways.

I was in a Chinese kindergarten, so like my Chinese is really good… In kindergarten, we learn early how to write sentences, so (but) later, the difference is bigger. And, I also feel like mixing the classes with locals is a really good thing… So, like we can communicate with them and try to exchange our languages…[Youth pursuing an associate degree, Nepalese, male, 20s, focus group]

I just came here three years ago. I was born in Hong Kong but I was studying in India. So, I just came three years ago, and then it was really hard for me to learn Cantonese.[Secondary 6 student, Indian, female, 10s, individual interview]

Some maybe… in Pakistan, Nepal, Philippines… Maybe come to Hong Kong after finishing Form 3 or Form 4 (roughly equivalent to U.S. Grade 9 or 10) there. When you come to Hong Kong, you may start at Form 4 or Form 3… But then, you may know nothing about Chinese… Turns out, there may be a great discrepancy regarding the [language] level… That means in a class of students, there can be some students that know nothing about Chinese, maybe some have been in Hong Kong for several years, but then, there may be some were born and raised in Hong Kong, so, in fact, there are different types of students…[Teacher, Chinese, 30s, male, individual interview]

However, even the locally born and educated students indicated difficulties in employment. Most of the participants were unable to cope with the mainstream HKDSE Chinese curriculum and had to opt for alternative Chinese courses, including the GCE, GCSE, and ApL(C). Even though the Hong Kong government has implemented the Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework in local primary/secondary schools to help non-Chinese-speaking students master the language since 2014 and has provided additional funding to primary and secondary schools to enable schools to adopt various intensive teaching modes for these students [43], youngsters, teachers, and employers all criticized the shortcomings of these alternative courses, which ultimately failed to meet workplace requirements.

What grade I… um… (Grade) A (in GCSE)… (But) I still don’t know how to write a sentence in Cantonese (Chinese)![Secondary 6 student, Filipino, male, 10s, individual interview]

What we are learning in the GCSE is really basic level Chinese. If you learn that in primary (school), you have the feel. I believe there are something harder than that, if not DSE… It is not sufficient. It is not really useful when you looking at the job especially. Lack of Cantonese in GCSE grade… I think the GCSE exam should be done in Primary 1 to Primary 3 already… P4–P6 should be another level. It should be separate standard.[Youth who pursued a bachler’s degree, Pakistani, female, 20s, focus group]

When entering the labour market, you then find that their Chinese language proficiency is not sufficient…That is insufficient for them to survive in society. This problem, in fact, needs… Well, not only to be handled by the schools… That is… to do it on our own in schools. There should be a consensus in society… The society that is the government to take action, or EDB [Education Bureau] needs to take action… i.e., to coordinate these works…That is the pedagogy… That is to design the overall syllabus… [including] the teaching materials.[Teacher, Chinese, 30s, female, individual interview]

GCSE is recognized (by the Police Force)… But getting an A star (grade) in GCSE doesn’t mean that you’re good at Chinese… Even after finishing university and getting an A star, your Chinese proficiency might still be weak. I’ve seen many (ethnically diverse) university students whose Chinese is really poor. Yes. We’ve interacted with (ethnically diverse) students from many universities… And even the most basic things, not reading, not writing, just communicating is already a problem.[Employer 9 from the police force, individual interview]

3.5. Environmental–Societal System: Employment Market with Limited Cultural Competence

According to our findings, when South and Southeast Asian individuals were rejected in job applications, the reasons often included that their cultural practices and the public image were not accepted by ethnic Chinese employers, colleagues, and the broader public.

I wore this [long] headscarf to the interview [in a private learning centre], and the interviewer asked me if I could take it off. I said the headscarf is for my religion. They said it was not safe, the students might be scared. They asked if it was clean. I said I can change to a shorter version; I change the scarf every day. It made feel… like I wasn’t accepted.[Youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Pakistani, female, 20s, focus group]

You should know there are some other people who is not like me but they are different race. They have different practice. You have to understand that thing. So Hong Kong people (have) no offence but I don’t know whether they are capable of doing that. A very good example is like that you take one Hong Kong local people who has study abroad and you take one local people who never been out of Hong Kong… There is a very big difference… We are more able to getting close to people who studied abroad… But you try to get connected with people who just live in Hong Kong, there is a gap. They will not understand what we are… I used to find this difference. I used to have this anger… There is some level of discrimination going on.[Working youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Nepalese, male, 20s, individual interview]

My company previously located in an industrial building. They (ethnic Chinese colleagues) always talked about the odor of some non-Chinese security guards… I did not know if they (ethnic Chinese colleagues) minded (working with ethnic diverse colleagues). However, they talked about that much… I do not worry about how they (ethnically diverse staff) work but I worry about how they work with my colleagues.[Employer 7 from a manufacturing company, individual interview]

Some employers claimed that the public image of South and Southeast Asian individuals was influenced by the social discourse and media representation, including negative news coverage of refugees, illegal labourers, and criminal gangs. These findings suggest that limited competence exists not only within workplaces but also across the broader employment market of the Hong Kong Chinese context.

Sometimes when I read the newspapers, there is news about South Asians committing crimes… (Has that affected your impression of South Asians?) It has had an impact, though I think it’s not really fair. But if I don’t hire those people, I don’t need to face that challenge.[Employer 1 from a security service and multimedia design company, individual interview]

South Asians! There’ve been more and more around Yuen Long (a district in Hong Kong) lately, and more robberies too… Probably not the locals (local ethnically diverse residents), maybe it’s the refugees (asylum seekers)… All my neighbour call them ‘Ah Cha’… They always say the same thing: be careful.[Employer 7 from a manufacturing company, individual interview]

3.6. Social Segregation

The final theme identified in the interview data is social segregation, which is not a subsystem in the STF. Rather, social segregation is considered the result of all the aforementioned influences. Our findings demonstrate that, as mentioned above, South and Southeast Asian students and their families often encountered difficulties in accessing information about further education and employment. The information poverty indicates the segregation between these ethnic groups and the Hong Kong Chinese society. This social segregation is also reflected in the job-seeking channels used by these groups. Even those with post-secondary qualifications often rely on their networks to seek jobs. As shared by our participants,

Mostly I try to find the job through my own network, or on my own contacts, for the places, they know me, and I know (them).[Unemployed youth who pursued a bachelor’s degree, Pakistani, male, 20s, individual interview]

It is just that sometimes when you are looking for a job… You have to have someone you know. So, for example, if you don’t know anybody who can tell you what… For example, like how I get my first job? [It is] because of my friend [who can help]… So I think the platform is my friend…It is hard for you to find a job… (It) would be nice to know that something can help you look for it.[Working youth without post-secondary education, Filipino, female, 20s, focus group]

You hired an ethnically diverse employee. And after working here, he/she felt the company was pretty good, so they’d introduce some of their friends to come… Even at my previous company, we had a Filipino colleague who introduced his son-in-law to come… I often ask our ethnically diverse staff if they can recommend any friends to come.[Employer 2 from a catering group, individual interview]

Although some employers reported that they welcomed non-Chinese applicants in Hong Kong, they did not receive any applications from these groups. As shared by some employers,

I have been responsible for recruitment for a certain period of time… I got applications from Italy and France but I did not receive a lot from those (ethnically diverse applicants) in local society. As an employer, I think it is strange.[Employer 5 from a wholesale and retail company, individual interview]

(Interviewer: Have you ever received job applications from local ethnic minorities?) No, not really… Mostly from overseas… JobsDB (a local online job search platform)!… When we post jobs there, about 80 to 90 percent of the applicants are from that group—maybe people from France, India, that kind of background. Local ones (ethnic minorities) are rare.[Employer 6 from an information technology company, individual interview]

4. Discussion

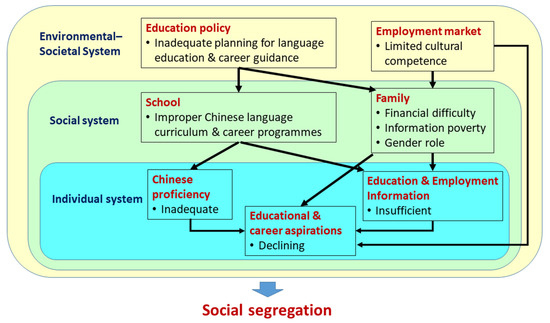

The school-to-work transition pathway of youths can be influenced by a wide range of factors. Although this study does not cover all of them, we identified seven key factors based on the STF. The influence of these seven factors is summarized in Figure 1. Directions of influence are indicated by the arrows. We argue that these seven factors are interrelated and can largely explain the disadvantages faced by South and Southeast Asian youths during their transition from school to work.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting the school-to-work transition of South and South Asian youths in the Hong Kong Chinese context.

4.1. Individual System

Within the individual system, we found that the aspirations of South and Southeast Asian youths in tertiary education and employment are noticeably lower than those of their counterparts still in secondary education. This suggests that their aspirations may be undermined by certain factors during the transition from secondary education to higher education or employment, leading to a loss of motivation for further study or career development.

From the interviews, we found that Chinese language proficiency within the individual system might be one of the factors affecting their aspirations. Although these young people may gain admission to post-secondary programmes through alternative Chinese qualifications such as GCSE and GCE, when exploring employment opportunities, they often realize that their Chinese language ability remains inadequate for meeting the basic requirements of the most jobs. Employers, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises focused on the local market, usually refuse to hire these young people due to their limited Chinese proficiency.

4.2. Social System

Within the social system, both families and schools contain factors that can erode those young people’s aspirations. The most prominent among these is financial hardship of family. As many South and Southeast Asian families tend to be in low-income situations, they are often unable to support their children in pursuing post-secondary education. Instead, they may expect their children to enter the workforce early to help relieve the family’s financial burden. Even though the government offers loans and financial aid, these parents often lack access to relevant information and are unfamiliar with the opportunities for higher education for their children. As a result, many South and Southeast Asian students are required to abandon pursuits of higher education and take up low-paid, unskilled jobs. Additionally, some Pakistani and Indian families, due to gender roles in their culture, expect their daughters to marry upon completing secondary school or even earlier, leading youths to discontinue their education.

Schools are meant to be key sources of information about further education and employment for students. However, our interview data revealed that many career-related activities fail to accommodate the needs of non-Chinese-speaking students. Schools also fall short in effectively raising awareness among these students about available career information, ultimately preventing them from accessing such resources in a timely manner. In addition, because of shortcomings in education policy, schools are unable to provide an appropriate Chinese language curriculum for non-Chinese-speaking students, which in turn leaves their Chinese proficiency below the general requirements of the employment market.

4.3. Environmental–Societal System

How have the aforementioned factors come to exist? Two contents within the environmental–societal system help explain their formation. The first one is the inadequacy of education policy. For many years, non-Chinese-speaking students who are unable to cope with the HKDSE Chinese curriculum have had no choice but to pursue alternative qualifications such as the GCSE and ApL(C). However, as mentioned earlier, these programmes do not equip students with the Chinese language proficiency required by the job market. Even those who complete post-secondary education may find their employment opportunities limited due to insufficient Chinese proficiency. Moreover, current policies do not support schools in offering tailored career guidance or employment-related activities for non-Chinese-speaking students. Consequently, those students often lack adequate information for making education and career plans.

The second factor is the limited cultural competence within the Hong Kong Chinese employment market and the wider society. Some young participants reported experiencing rejection based on their ethnic attire during job interviews. Some employers admitted concerns that hiring South and Southeast Asian individuals might influence the image of the companies. These cultural stereotyping and exclusion of South and Southeast Asian individuals are linked to negative media representation and hostile social discourse. This may explain why many South and Southeast Asian individuals, including older generations, have faced unequal treatment in employment and other aspects of daily life, often being forced into low-income jobs that contribute to ongoing financial hardship.

4.4. Social Segregation

The lack of cultural competence within society has left South and Southeast Asian individuals feeling socially excluded. Combined with the long-standing failure of Chinese language education policies, generations of these underrepresented groups have been left with inadequate Chinese proficiency, hindering their ability to integrate into Hong Kong Chinese society. The result is persistent social segregation between the Chinese society and ethnically diverse communities. One of the examples is that South and Southeast Asian parents often lack understanding of educational resources, and their children, despite holding post-secondary qualifications, tend to rely on ethnic networks to seek jobs. Even when job advertisements are posted in English, employers report receiving no applications from local ethnically diverse individuals.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we focus on the social genre of the four largest ethnically diverse groups, namely Pakistani, Nepalese, Filipino and Indian populations, and illuminate the fact that they have been disadvantaged in Hong Kong, which proclaims itself a world city with rich and diverse cultures. Through the lens of the STF, we uncover and critically examine the contextual barriers faced by the youths of these ethnic groups in the pathways of school advancement and school-to-work transition. We found that despite the high aspiration in the period of secondary education, the educational and career aspirations of South and Southeast Asian youths are eroded by numerous interrelated obstacles, which are not the natural consequences of being from different ethnic origins or individual incompetence. Rather, we argue that most of these barriers are largely attributed by two major factors embedded in the Hong Kong Chinese context, namely the education policy and cultural competence. Deficiencies in education policy led to ethnically diverse students’ inadequate Chinese language proficiency, which in turn hinders their access to further education and employment information and restricts their capacity to meet the language requirements of the labour market. The limited cultural competence within Hong Kong Chinese society not only hinders equal access to the job market for ethnically diverse youths but also keeps the older generation of these ethnic groups in low-paid, elementary jobs, reducing their financial capacity to support their children’s pursuit of higher education. These two contents in the environmental–societal system led to social segregation between the disadvantaged ethnic diverse groups and the ethnic Chinese population. This problem has further reinforced social disadvantages of these groups of young people. This creates a vicious cycle whose impact is too overwhelming to overcome. Piecemealed services are no longer adequate to address these problems and their perpetuation. Without a fundamental policy reconsideration with an aim to bring about genuine racial equality to help create transitional pathways for these ethnically diverse youths, equal opportunity in youth transition will remain a myth.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, there is a sample selection issue. Although purposive sampling was used to recruit participants with diverse demographic backgrounds at different stages of the school-to-work transition, it was difficult to construct a sample composition that perfectly matched the demographic profiles of the four ethnic groups in this study. Consequently, the representativeness of the results is lower than that of quantitative studies based on probability sampling, though it is believed that to a large extent, the findings of this study can be applied to other situations in a similar context. Second, the findings are largely based on case narratives, and the analysis lacks systematic quantitative support. Third, because the sample size for each ethnic group is small, in-depth comparison across groups is difficult. Finally, the main purpose of this manuscript is to highlight the crucial role of structural factors in the school-to-work transition of South and Southeast Asian youths in the Hong Kong Chinese context. The concreteness of our policy recommendations is limited to the operational level.

In future research, a more balanced sample that includes more participants from each ethnic group at each stage of the transition and a more systematic analysis with quantitative support should be considered. In addition, an in-depth study of existing education and social inclusion policies is needed for constructing concrete policy recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-K.C. and E.Y.-N.C.; methodology, B.-K.C. and E.Y.-N.C.; formal analysis, Y.-M.C. and S.T.-M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.T.-M.C., E.Y.-N.C. and B.-K.C.; project administration, S.T.-M.C.; funding acquisition, B.-K.C. and E.Y.-N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Equal Opportunities Commission of Hong Kong (fund number 178136).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Research Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Baptist University approved this study (protocol code REC/18-19/0327 and 19 March 2019 of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the schools and social service agencies involved in this study, particularly the youngsters, students, teachers, and parents, for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ApL(C) | Applied Learning Chinese |

| EM | Ethnic Minority |

| GCE | General Certificate of Education |

| GCSE | General Certificate of Secondary Education |

| IGCSE | International General Certificate of Secondary Education |

| HKDSE | Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education |

| STF | Systems Theory Framework |

References

- Forsyth, A.; Furlong, A. Access to higher education and disadvantaged young people. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 29, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A.; Cartmel, F. Young People and Social Change: Individualization and Risk in Late Modernity; Open University Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann, A.C.; Menze, L.; Solga, H. Persistent disadvantages or new opportunities? The role of agency and structural constraints for low-achieving adolescents’ school-to-work transitions. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 2091–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, W.C. Opportunities, challenges, and transitions: Educational aspirations of Pakistani migrant youth in Hong Kong. Child. Geogr. 2018, 16, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyne, S.; Gebel, M. Education effects on the school-to-work transition in Egypt: A cohort comparison of labor market entrants 1970–2012. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 46, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, K. School to Work Transition in Japan: An Ethnographic Study; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.K. Social Security Policy in Hong Kong: From British Colony to Special Administrative Region of China; The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group: Lanham, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.; Wong, V. Social policy in Hong Kong: From British colony to the Special Administrative Region of China. Eur. J. Soc. Work 1998, 1, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.; Wong, H.; Wong, W.P. Deprivation and poverty in Hong Kong. Soc. Policy Adm. 2019, 53, 556–575. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.B. Choosing a vocation at 100: Time, change, and context. Career Dev. Q. 2009, 57, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personality and Work Environments; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D.E. A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In Career Choice and Development: Applying Contemporary Approaches to Practice, 2nd ed.; Brown, D., Brooks, L., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 197–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career construction theory and practice. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 3rd ed.; Lent, R.W., Brown, S.D., Eds.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 165–199. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, M.; Patton, W. Development of a systems theory of career development. Aust. J. Career Dev. 1995, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, W.; McMahon, M. Career Development and Systems Theory: Connecting Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, K.-T.; Lee, C.-K.J.; Hui, K.-F.S.; Chun, W.-S.D.; Chan, N.-C.K. Academic and career aspiration and destinations: A Hong Kong perspective on adolescent transition. Educ. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3421953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, N. An exploratory analysis of Australian classical undergraduate brass musicians’ career aspirations using systems theory framework of career development. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2025, 34, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, T.W.; Mills, M.T.; Lapka, S. The influence of linguistic profiling on perceived employability: A new application of the systems theory framework of career development. Career Dev. Int. 2024, 29, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychology Association. Website of APA Style: Racial and Ethnic Identity. 2024. Available online: https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/racial-ethnic-minorities (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Office of Human Rights; Mayor’s Office of Racial Equity. Guide to Inclusive Language: Race and Ethnicity. The Government of the District of Columbia. 2022. Available online: https://ohr.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ohr/page_content/attachments/OHR_ILG_RaceEthnicity_FINAL%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Census and Statistics Department. 2016 Population Census: Thematic Report: Ethnic Minorities; Hong Kong SAR Government: Hong Kong, China, 2017.

- Census and Statistics Department. 2021 Population Census: Thematic Report: Ethnic Minorities; Hong Kong SAR Government: Hong Kong, China, 2022.

- Census and Statistics Department. 2021 Population Census: Main Table: A117b Population (Excluding Foreign Domestic Helpers) by Sex, Age, Year and Ethnicity. Hong Kong SAR Government. 2023. Available online: https://www.census2021.gov.hk/en/main_tables.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Arfeen, B. Graduate Employability of South Asian Ethnic Minority Youths: Voices from Hong Kong; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Law, K.Y.; Lee, K.M. Importing western values versus indigenization: Social work practice with ethnic minorities in Hong Kong. Int. Soc. Work 2016, 59, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.M.; Chan, B.K.; Cho, E.Y.N.; Chan, Y.M. A Study of Education and Career Pathways of Ethnic Minority Youth in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Equal Opportunities Commission in conjunction with the Centre for Youth Research and Practice; Hong Kong Baptist University: Hong Kong, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Unison. A Comprehensive Review of Learning and Teaching of Chinese for Ethnic Minority Students in Hong Kong 2006–2016; Hong Kong Unison: Hong Kong, China, 2018; Available online: http://www.unison.org.hk/DocumentDownload/Researches/R201805%20A%20comprehensive%20review%202006-2016_final.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Education Bureau, the Government of HKSAR. Acceptance of Alternative Qualification(s) in Chinese Language for JUPAS Admission. 2022. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/student-parents/ncs-students/about-ncs-students/jupas-admission.html (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Hong Kong Unison. Racial Acceptance Survey Report. Hong Kong Unison. 2012. Available online: http://www.unison.org.hk/DocumentDownload/Researches/R201203%20Racial%20Acceptance%20Survey%20Report.pdf?subject=Enquiry%20for%20Research%20hard%20copy (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Cheung, K.C.K.; Chou, K.L. Child poverty among Hong Kong ethnic minorities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 137, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loper, K. Race and Equality: A study of Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong’s Education System; Occasional Paper 12; Centre for Comparative and Public Law, University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Law, K.Y.; Lee, K.M. Socio-political embeddings of South Asian ethnic minorities’ economic situations in Hong Kong. J. Contemp. China 2013, 22, 984–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Burgess, R. Qualitative Research. Sage: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Seale, C. (Ed.) Social Research Method: A Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. (Ed.) Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baan, N.v.d.; Gast, I.; Gijselaers, W.; Beausaert, S. Coaching to prepare students for their school-to-work transition: Conceptualizing core coaching competences. Educ. Train. 2022, 64, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic analysis: An analytical tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, K.S. A Qualitative Program Evaluation on the Efficacy of a Workforce Training and Education Program. Unpublished D.P.A. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2018. Available online: http://pqdd.sinica.edu.tw.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/doc/10747755 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Research Office of the Legislative Council Secretariat. Statistical Highlight: Educational Support for Non-Chinese Speaking Students. 2020. Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1920issh33-educational-support-for-non-chinese-speaking-students-20200708-e.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).