Adolescent Profiles Amid Substantial Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Latent Profile Analysis on Personality, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Analytic Sample

2.3. Measures

2.4. Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Interpretation of Latent Profiles

3.2. Latent Profiles and Demographic Factors

4. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keyes, K.M.; Gary, D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Hamilton, A.; Schulenberg, J. Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.M.; Copeland, K.A.; Sucharew, H.; Kahn, R.S. Social-emotional problems in preschool-aged children: Opportunities for prevention and early intervention. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balistreri, K.S.; Alvira-Hammond, M. Adverse childhood experiences, family functioning and adolescent health and emotional well-being. Public Health 2016, 132, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D. Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: A multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, D.; Armour, C. Symptom Trajectories Among Child Survivors of Maltreatment: Findings from the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN). J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2016, 44, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Doernberger, C.H.; Zigler, E. Resilience is not a unidimensional construct: Insights from a prospective study of inner-city adolescents. Dev. Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in Development and Psychopathology: Multisystem Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Murphy, K.; Jefferies, P. Researching Multisystemic Resilience: A Sample Methodology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 607994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, F.R.; Disabato, D.J.; Kashdan, T.B.; Machell, K.A. Personality Strengths as Resilience: A One-Year Multiwave Study. J. Pers. 2017, 85, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubowitz, H.; Thompson, R.; Proctor, L.; Metzger, R.; Black, M.M.; English, D.; Poole, G.; Magder, L. Adversity, Maltreatment, and Resilience in Young Children. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Pei, F.; Logan, J.; Helsabeck, N.; Hamby, S.; Slesnick, N. Early childhood maltreatment and profiles of resilience among child welfare-involved children. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 35, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S. Resilience: Impact on Child Psychosocial Development|Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. 1 October 2013. Available online: https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/resilience/according-experts/resilience-early-age-and-its-impact-child-psychosocial-development (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Yoon, S.; Helsabeck, N.; Wang, X.; Logan, J.; Pei, F.; Hamby, S.; Slesnick, N. Profiles of Resilience among Children Exposed to Non-Maltreatment Adverse Childhood Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Torteya, C.; Miller-Graff, L.E.; Howell, K.H.; Figge, C. Profiles of Adaptation Among Child Victims of Suspected Maltreatment. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 46, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Struck, S.; Taillieu, T.; Salmon, S.; Fortier, J.; Brownell, M.; Chartier, M.; Yakubovich, A.R.; Afifi, T.O. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Education Outcomes among Adolescents: Linking Survey and Administrative Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Kim, I.; Nam, S.; Jeong, J. Adverse childhood experiences and the associations with depression and anxiety in adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Heath, R.D.; Majewski, D.; Blake, C. Adverse childhood experiences and child behavioral health trajectory from early childhood to adolescence: A latent class analysis. Child. Abuse Negl. 2022, 134, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytilä-Manninen, M.; Haravuori, H.; Fröjd, S.; Marttunen, M.; Lindberg, N. Mediators between adverse childhood experiences and suicidality. Child. Abus. Negl. 2018, 77, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad, J.E. Social consequences and contexts of adverse childhood experiences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichman, N.E.; Teitler, J.O.; Garfinkel, I.; McLanahan, S.S. Fragile families: Sample and design. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2001, 23, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Monnat, S.M. Racial/ethnic differences in clusters of adverse childhood experiences and associations with adolescent mental health. SSM—Popul. Health 2022, 17, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child. Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T.K.A.; Slack, K.S.; Berger, L.M. Adverse childhood experiences and behavioral problems in middle childhood. Child. Abus. Negl. 2017, 67, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Xi, W.; Gump, B.B.; Vasilenko, S.A. Racial Differences in Adverse Childhood Experiences: Timing and Patterns. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 68, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.; Donnelly, D. Beating the Devil Out of Them: Corporal Punishment in American Children, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinking Levels Defined|National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Mroczek, D.; Ustun, B.; Wittchen, H. The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 1998, 7, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaefer, H.L.; Edin, K.; Talbert, E. Understanding the Dynamics of $2-a-Day Poverty in the United States. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 1, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Benson, L.; Steinberg, E.A.; Steinberg, L. The EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-Being. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Dumenci, L.; Rescorla, L.A. Rating of Relations Between DSM-IV Diagnostic Categories and Items of the CBCL/6-18, TRF, and YSR; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.E.; Scott, K.G.; Bauer, C.R. The Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (Asbi): A New Assessment of Social Competence in High-Risk Three-Year-Olds. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1992, 10, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, F.M.; Elliott, S.N.; Kettler, R.J. Base rates of social skills acquisition/performance deficits, strengths, and problem behaviors: An analysis of the Social Skills Improvement System—Rating Scales. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. Mplus, version 8; computer software; 1998–2017; Muthén Muthén: Los Angel, CA, USA, 2017.

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, S.L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D. Mixtures of Factor Analyzers. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Machine Learning, Stanford, CA, USA, June 29–2 July 2000; ICML ’00. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: Burlington, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 599–606. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Desarbo, W.S.; Reibstein, D.J.; Robinson, W.T. An Empirical Pooling Approach for Estimating Marketing Mix Elasticities with PIMS Data. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Resampling methods in Mplus for complex survey data. Struct. Equ. Model. 2010, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Bistricky, S.L.; Gallagher, M.W.; Roberts, C.M.; Ferris, L.; Gonzalez, A.J.; Wetterneck, C.T. Frequency of Interpersonal Trauma Types, Avoidant Attachment, Self-Compassion, and Interpersonal Competence: A Model of Persisting Posttraumatic Symptoms. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 2017, 26, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mustanski, B.; Dick, D.; Bolland, J.; Kertes, D.A. Protective Factors Buffer Life Stress and Behavioral Health Outcomes among High-Risk Youth. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2019, 47, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, S.J.; Ford, J.L. Protective Factors to Promote Health and Flourishing in Black Youth Exposed to Parental Incarceration. Nurs. Res. 2021, 70 (Suppl. S5), S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Min–Max | M (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social skills | 0.25–2.00 | 1.38 (0.32) | |

| Internalizing behavior competence | 0.13–2.00 | 1.70 (0.33) | |

| Externalizing behavior competence | 0.35–2.00 | 1.71 (0.28) | |

| Optimism | 1–4 | 3.38 (0.50) | |

| Perseverance | 1.25–4 | 3.42 (0.48) | |

| Academic achievement | 1–4 | 2.76 (0.65) | |

| ACEs (by age 9) | |||

| Psychological abuse | 684 (47.9%) | ||

| Physical abuse | 513 (35.9%) | ||

| Domestic violence | 307 (21.5%) | ||

| Maternal substance abuse | 884 (61.9%) | ||

| Maternal depression | 654 (45.8%) | ||

| Paternal incarceration | 389 (27.3%) | ||

| Parental divorce or separation | 1270 (89.0%) | ||

| Neglect | 546 (38.3%) | ||

| Family poverty | 1362 (95.4%) | ||

| Maternal low education | 583 (40.9%) | ||

| ACEs Sum | 4–10 | 5.04 (1.15) | |

| Mother’s age (at child’s birth age) | 15–43 | 23.49 (5.32) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Black | 844 (59.1%) | ||

| Hispanic | 219 (15.3%) | ||

| White | 330 (23.1%) | ||

| Other | 34 (2.4%) | ||

| Child’s sex | |||

| Male | 766 (53.7%) | ||

| Female | 661 (46.3%) |

| Classes | AIC | BIC | aBIC | LRT (p) | BLRT (p) | Entropy | Smallest Class Size (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytic sample | Class-1 | 8474.693 | 8537.853 | 8499.733 | -- | -- | ||

| (n = 1427) | Class-2 | 7629.777 | 7729.781 | 7669.424 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.881 | 250 (17.5%) |

| Class-3 | 7341.416 | 7478.262 | 7395.669 | 0.0042 | 0.0000 | 0.724 | 217 (15.2%) | |

| Class-4 | 7135.417 | 7309.107 | 7204.278 | 0.2447 | 0.0000 | 0.758 | 47 (3.3%) | |

| Class-5 | 6967.636 | 7178.169 | 7051.103 | 0.0285 | 0.0000 | 0.779 | 32 (2.2%) | |

| Class-6 | 6849.897 | 7079.274 | 6947.971 | 0.7111 | 0.0000 | 0.776 | 29 (2.0%) |

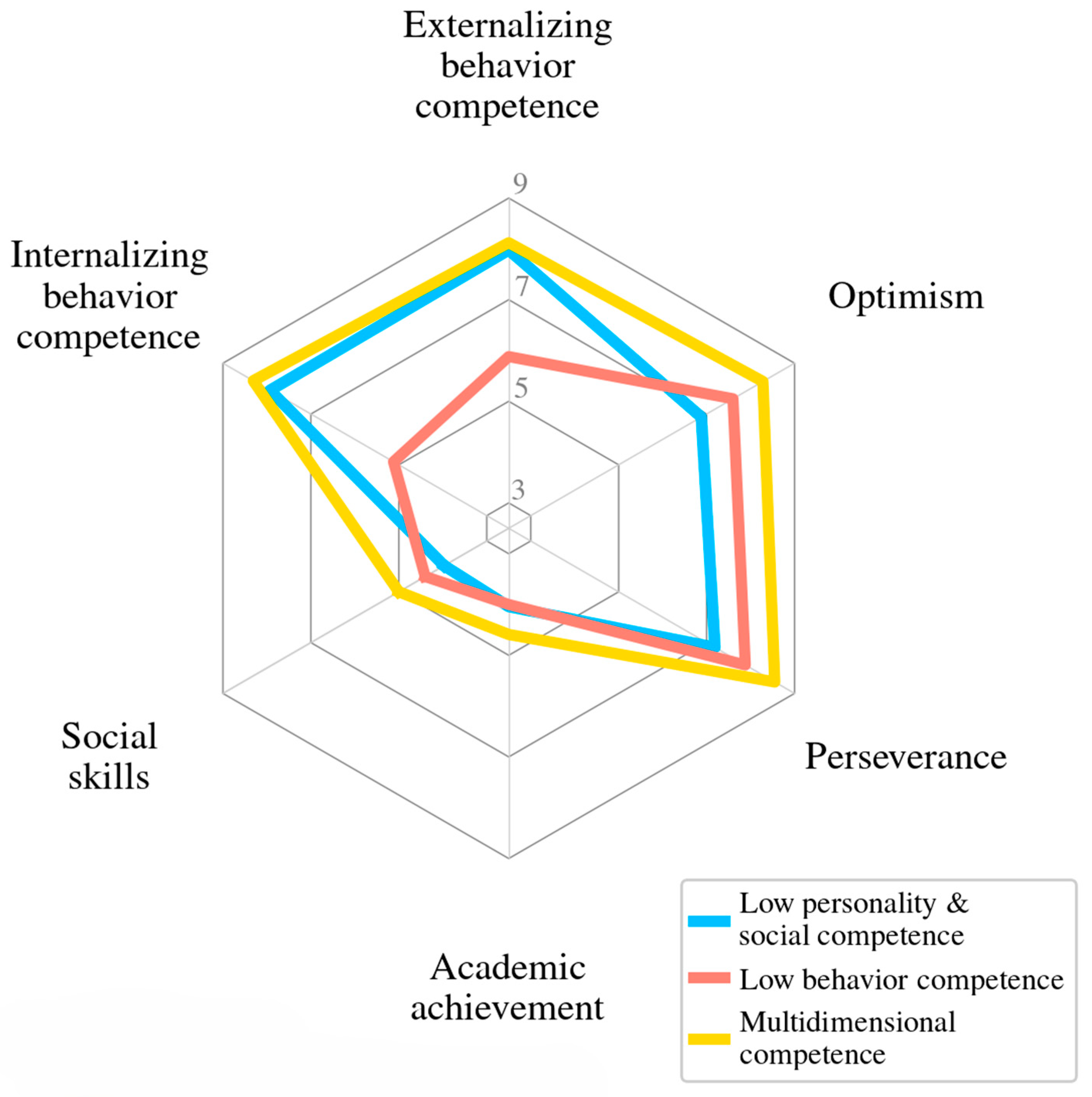

| A | ||||

| Low Personality & Social Competence (n = 340, 23.8%) | Low Behavioral Competence (n = 217, 15.2%) | Multidimensional Competence (n = 871, 61.0%) | Tests of Significance | |

| M | M | M | ||

| Social skills | 1.17 | 1.30 | 1.48 | 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Internalizing behavior competency | 1.74 | 1.12 | 1.82 | 2 < 1 < 3 |

| Externalizing behavior competency | 1.73 | 1.31 | 1.81 | 2 < 1 < 3 |

| Optimism | 2.97 | 3.28 | 3.57 | 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Perseverance | 3.02 | 3.31 | 3.60 | 1 < 2 <3 |

| Academic achievement | 2.54 | 2.52 | 2.89 | 1 = 2; 1 < 3; 2 < 3; |

| B | ||||

| M | M | M | ||

| Social skills | 3.97 | 4.40 | 5.00 | 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Internalizing behavior competency | 7.93 | 5.12 | 8.31 | 2 < 1 < 3 |

| Externalizing behavior competency | 7.98 | 5.88 | 8.12 | 2 < 1 < 3 |

| Optimism | 6.88 | 7.60 | 8.28 | 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Perseverance | 7.19 | 7.88 | 8.55 | 1 < 2 <3 |

| Academic achievement | 4.04 | 4.00 | 4.59 | 1 = 2; 1 < 3; 2 < 3; |

| Low Personality &Social Competence | Low Behavioral Competence | |

|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | |

| Mother’s age | 1.03 [1.00, 1.06] † | 0.99 [0.96, 1.02] |

| Race and ethnicity (ref: White) | ||

| Black | 0.57 [0.33, 0.97] * | 0.41 [0.26, 0.63] *** |

| Hispanic | 0.95 [0.53, 1.71] | 0.43 [0.25, 0.74] ** |

| Other race | 0.84 [0.24, 2.88] | 0.65 [0.22, 1.94] |

| Adolescent’s gender (ref: male) | ||

| Female | 0.95 [0.44, 1.29] | 1.05 [0.74, 1.48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Merrin, G.J. Adolescent Profiles Amid Substantial Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Latent Profile Analysis on Personality, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes. Adolescents 2025, 5, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040060

Wang X, Zhang X, Merrin GJ. Adolescent Profiles Amid Substantial Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Latent Profile Analysis on Personality, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiafei, Xiaoyan Zhang, and Gabriel J. Merrin. 2025. "Adolescent Profiles Amid Substantial Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Latent Profile Analysis on Personality, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040060

APA StyleWang, X., Zhang, X., & Merrin, G. J. (2025). Adolescent Profiles Amid Substantial Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Latent Profile Analysis on Personality, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes. Adolescents, 5(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040060