The Relationship Between Kindness and Transgressive Behaviors in Adolescence: The Moderating Role of Self-Importance of Moral Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Kindness: A Multidimensional Moral Construct

1.2. Moral Identity: The Foundation of Moral Self-Conception

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Kindness Scale [47]

- -

- Stage 1 (egocentric): kindness is driven solely by personal interest and is considered selfish and subjective (“I am a kind person because it is easier to get what I want”, α = 0.89; Ω = 0.88).

- -

- Stage 2 (social/normative): kindness is viewed as recognizing reciprocal relationships, though it is still motivated by self-interest (“I am kind when it serves any purpose”, α = 0.58; Ω = 0.60).

- -

- Stage 3 (extrinsically motivated): kindness is extrinsically motivated, as people begin to consider the perspectives of themselves and others (“I am kind so that I seem as nice as others”, α = 0.65; Ω = 0.66).

- -

- Stage 4 (authentic): kindness is based on mutual respect and societal perspective, where individuals believe in respecting others (“I am kind because I believe in respecting the dignity of others”, α = 0.77; Ω = 0.78).

2.2.2. Self-Importance of Moral Identity [59]

2.2.3. Self-Report of Antisocial Behavior [6,9]

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

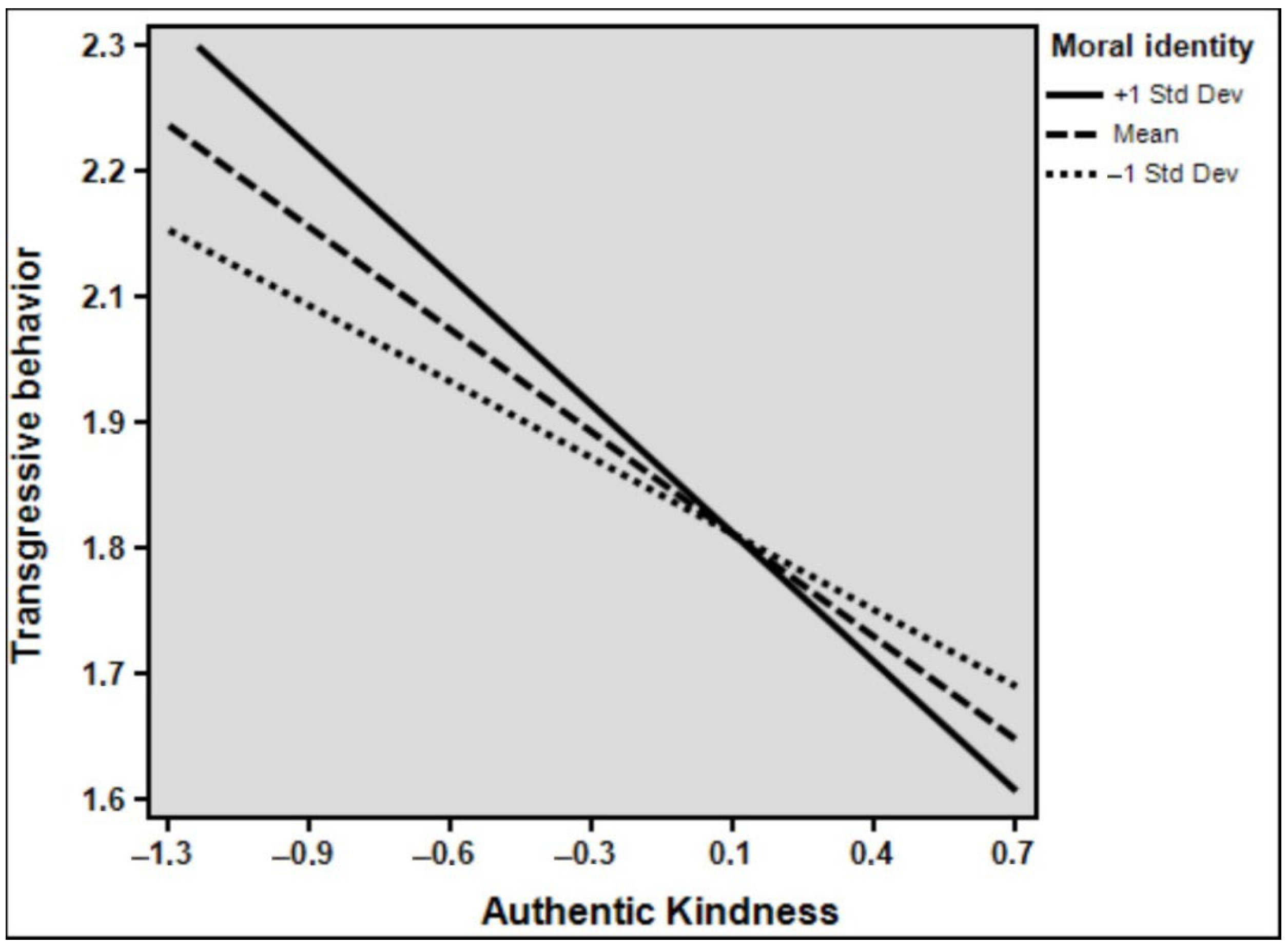

3.2. Moderated Regression

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palmonari, A. Psicologia dell’adolescenza; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Smith, I.; Pass, L.; Reynolds, S. How adolescents understand their values: A qualitative study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, N.; Koglin, U. The association between moral identity and moral decisions in adolescents. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 179, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, T.E. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N.; Crocetti, E.; Branje, S.; Van Lier, P.; Meeus, W. Linking delinquency and personal identity formation across ado-lescence: Examining between and within-person associations. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 2182–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesner, J. Depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Their relations with classroom problem behavior and peer status. J. Res. Adolesc. 2002, 12, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Danioni, F.; Barni, D. La relazione tra disimpegno morale e comportamenti trasgressivi in adole-scenza: Il ruolo moderatore dell’alessitimia. Psicol. Clin. Dello Svilupp. 2019, 23, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Zagrean, I.; Mangialavori, S.; Danioni, F.V.; Cacioppo, M.; Barni, D. Comportamenti di uso problematico in adolescenza: Il ruolo dei valori personali come fattori di protezione e di rischio. Psicol. Soc. 2019, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesner, J.; Pastore, M. Differences in the relations between antisocial behavior and peer acceptance across contexts and across adolescence. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 1278–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.; Ryan, R. What adolescents need: A self-determination theory perspective on development within families, school, and society. In Academic Motivation of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing Inc.: Char-lotte, NC, USA, 2002; pp. 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T. Main and moderated effects of moral cognition and status on bullying and defending. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoga Ratnam, K.K.; Nik Farid, N.D.; Wong, L.P.; Yakub, N.A.; Abd Hamid, M.A.I.; Dahlui, M. Exploring the decisional drivers of deviance: A qualitative study of institutionalized adolescents in Malaysia. Adolescents 2022, 2, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Bean, D.S.; Olsen, J.A. Moral Identity and Adolescent Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors: Interactions with Moral Disengagement and Self-Regulation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 44, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenders, I.; Brugman, D. Moral/Non-moral Domain Shift in Young Adolescents in Relation to Delinquent Behaviour. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 23, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, V.; Gibbs, J.C.; Basinger, K.S. Patterns of Developmental Delay in Moral Judgment by Male and Female Delinquents. Merrill-Palmer Q. 1994, 538–553. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23087922 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Brugman, D.; Podolskij, A.; Heymans, P.; Boom, J.; Karabanova, O.; Idobaeva, O. Perception of Moral Atmosphere in School and Norm Transgressive Behaviour in Adolescents: An Intervention Study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2003, 27, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo Rico, D.; Panesso Giraldo, C.; Arbeláez Caro, J.S.; Cabrera Gutiérrez, G.; Isaac, V.; Escobar, M.J.; Herrera, E. Moral Disengagement in Adolescent Offenders: Its Relationship with Antisocial Behavior and Its Presence in Offenders of the Law and School Norms. Children 2024, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A. Bridging Moral Cognition and Moral Action: A Critical Review of the Literature. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.; Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E.; Malti, T.; Hymel, S. Moral Reasoning and Emotion Attributions of Adolescent Bullies, Victims, and Bully-victims. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 30, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Bussey, K. Moral Disengagement in Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. Dev. Rev. 2023, 70, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The psychology of moral development: The nature and validity of moral stages. In Essays on Moral Development; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci, L.P. The development of moral reasoning. In Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development; Goswami, U., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 303–325. [Google Scholar]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Morrison, E.M.; Liau, A.K.; Gibbs, J.C. Moral Cognition: Explaining the Gender Difference in Antisocial Behavior. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 2001, 47, 532–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Walker, L.J.; Olsen, J.A.; Woodbury, R.D.; Hickman, J.R. Moral Identity as Moral Ideal Self: Links to Adolescent Outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuther, T.L. Moral Reasoning, Perceived Competence, and Adolescent Engagement in Risky Activity. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, J.P. Moral Identity: From Theory to Research. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2025. Available online: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2743 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Liao, J.; Jin, Z. The Relationship between Moral Sensitivity and Prosocial Behavior in College Students: The Mediating Roles of Moral Disengagement and Reciprocity Norms. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1508962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Huang, N.; Li, P.; Li, D.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Z. The Relationship between Moral Identity and Prosocial Behavior in Adolescents: The Parallel Mediating Roles of General Belongingness and Moral Elevation. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 3726–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algoe, S.B.; Haidt, J. Witnessing Excellence in Action: The ‘Other-Praising’Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doris, J.; Stich, S.; Phillips, J.; Walmsley, L. Moral psychology: Empirical approaches. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/moral-psych-emp/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Ellemers, N.; Van Der Toorn, J.; Paunov, Y.; Van Leeuwen, T. The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published from 1940 through 2017. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 23, 332–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Medin, D.L. Construal Levels and Moral Judgment: Some Complications. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2012, 7, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R.B.; Bodine, A.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Basinger, K.S. What Accounts for Prosocial Behavior? Roles of Moral Identity, Moral Judgment, and Self-Efficacy Beliefs. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Jain, K.; Behl, A. Effect of Service Transgressions on Distant Third-Party Customers: The Role of Moral Identity and Moral Judgment. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Quantitative judgment in social perception. Br. J. Psychol. 1959, 50, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Oakes, P.J. The Significance of the Social Identity Concept for Social Psychology with Reference to Individualism, Interactionism and Social Influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 25, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadera, A.K.; Pathki, C.S. Competition and Cheating: Investigating the Role of Moral Awareness, Moral Identity, and Moral Elevation. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, D. Cyberbullying Perpetration among Chinese Adolescents: The Role of Interparental Conflict, Moral Disengagement, and Moral Identity. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 86, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, S.; Sun, B. Stay Hungry for Morality: The Inhibitory Effect of High Moral Identity and Moral Elevation on Moral Licensing. J. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, W.; Wisneski, D.C.; Brandt, M.J.; Skitka, L.J. Morality in everyday life. Science 2014, 345, 1340–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibis, D.; Hookway, N.; Vreugdenhil, A. Kindness in Australia: An Empirical Critique of Moral Decline Sociology. Br. J. Sociol. 2016, 67, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C. Understanding Kindness–A Moral Duty of Human Resource Leaders. J. Values-Based Leadersh. 2017, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yagil, D. Display Rules for Kindness: Outcomes of Suppressing Benevolent Emotions. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.L.; O’Donovan, A.; Pepping, C.A. Can Gratitude and Kindness Interventions Enhance Well-Being in a Clinical Sample? J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, A.; Israel, S. Empathy, prosocial behavior, and other aspects of kindness. In Handbook of Temperament; Zentner, M., Shiner, R.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Malti, T. Kindness: A Perspective from Developmental Psychology. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 629–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunian, A.L. The Kindness Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 83, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Sheldon, K.M.; Schkade, D. Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillington, K.J.; Johnson, A.M.; Mantler, T.; Irwin, J.D. Kindness as an Intervention for Student Social Interaction Anxiety, Affect, and Mood: The KISS of Kindness Study. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 6, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, D.T.; McClintock, A.S.; Anderson, T. Does Loving-Kindness Meditation Reduce Anxiety? Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Mateo, N.J.; Natale, S. The Mental Health Benefits of Kindness-Oriented Schools: School Kindness Is Associated with Increased Belongingness and Well-Being in Filipino High School Students. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckler, A.; Tusche, A.; Schmidt, P.; Singer, T. Distinct Mental Trainings Differentially Affect Altruistically Motivated, Norm Motivated, and Self-Reported Prosocial Behaviour. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.; Sehmbi, T.; Smith, P. Effects of Kindness-and Compassion-Based Meditation on Wellbeing, Prosociality, and Cognitive Functioning in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2103–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L. Kindness: Society’s Golden Chain. Psychologist 2018, 31, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Tenbrunsel, A.E. Blind Spots: Why We Fail to Do What’s Right and What to Do About it; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zagrean, I.; Cavagnis, L.; Danioni, F.; Russo, C.; Cinque, M.; Barni, D. More Kindness, Less Prejudice against Immigrants? A Preliminary Study with Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Carlo, G. Moral Identity: What Is It, How Does It Develop, and Is It Linked to Moral Action? Child Dev. Perspect. 2011, 5, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, W.; Hart, D. Self-understanding and its role in social and moral development. In Developmental Psychology: An Ad-vanced Textbook, 3rd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Lamb, M.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 421–464. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, K.; Reed II, A. The Self-Importance of Moral Identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Carlo, G. Identity as a Source of Moral Motivation. Hum. Dev. 2005, 48, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Aquino, K.; Levy, E. Moral Identity and Judgments of Charitable Behaviors. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Aquino, K.; Mittal, V.; Swartz, R. When Moral Identity Symbolization Motivates Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Recognition and Moral Identity Internalization. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S.G.; Krettenauer, T. Does Moral Identity Effectively Predict Moral Behavior?: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016, 20, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Lefebvre, J.P.; Hardy, S.A.; Zhang, Z.; Cazzell, A.R. Daily Moral Identity: Linkages with Integrity and Compassion. J. Pers. 2022, 90, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; McFerran, B.; Laven, M. Moral Identity and the Experience of Moral Elevation in Response to Acts of Uncommon Goodness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, J.P.; Krettenauer, T. Linking Moral Identity with Moral Emotions: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, M.; Lalot, F.; Heering, M.S. Moral Identity, Moral Self-Efficacy, and Moral Elevation: A Sequential Mediation Model Predicting Moral Intentions and Behaviour. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, P.; Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M. Moral Values and Moral Identity Moderate the Indirect Relationship between Sport Supplement Use and Doping Use via Sport Supplement Beliefs. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Nasser Taha Ibrahim Mohamed, A.M.A.S. Moral Identity as Moderator in the Relationship between Machiavellian Leadership Perception and Employees’ Opportunistic Behaviors. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Long, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, W. A Social Exchange Perspective of Employee–Organization Relationships and Employee Unethical pro-Organizational Behavior: The Moderating Role of Individual Moral Identity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Williams, K.A. Ethical Leadership, Subordinates’ Moral Identity and Self-Control: Two-and Three-Way Interaction Effect on Subordinates’ Ethical Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 165, 114044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.K.; Meade, A.W. Applying Social Psychology to Prevent Careless Responding during Online Surveys. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 67, 231–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, P.A.; Tix, A.P.; Barron, K.E. Testing Moderator and Mediator Effects in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. Interaction! Computer Software. 2013. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/Interaction/free.aspx (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunner-Winkler, G. Development of Moral Motivation from Childhood to Early Adulthood. J. Moral Educ. 2007, 36, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.S.; Coffman, D.L.; Stuart, E.A.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Vegetabile, B.; McCaffrey, D.F. Practical Challenges in Mediation Analysis: A Guide for Applied Researchers. Heal. Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binfeta, J.T.; Whitehead, J. The Effect of Engagement in a Kindness Intervention on Adolescents’ Well-Being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2019, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M | SD | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Egocentric kindness | 1.73 | 0.76 | 1.00–4.00 | 1.00 | 0.47 | − | 0.28 ** | 0.10 | −0.22 ** | −0.15 * | 0.38 ** |

| 2. Social/normative kindness | 2.95 | 0.51 | 1.60–4.00 | −0.19 | −0.01 | − | 0.35 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| 3. Extrinsically motivated kindness | 2.94 | 0.53 | 1.60–4.00 | 0.29 | −0,18 | − | 0.52 ** | 0.37 ** | −0.10 | ||

| 4. Authentic kindness | 3.27 | 0.48 | 2.00–4.00 | −0.13 | 0.71 | − | 0.47 ** | −0.29 ** | |||

| 5. Self-importance of moral identity | 3.47 | 0.56 | 1.80–5.00 | 0.16 | 0.17 | - | −0.16 ** | ||||

| 6. Transgressive behaviors | 1.82 | 0.49 | 1.00–4.00 | 0.49 | 1.66 | - |

| Transgressive Behaviors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | ||||||

| Predictors | B | SE | Lower | Upper | β | p |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

| Gender | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.41 |

| Egocentric kindness | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.01 |

| Social/normative kindness | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| Extrinsically motivated kindness | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.66 |

| Authentic kindness | −0.24 | 0.08 | −0.41 | −0.07 | −0.24 | 0.01 |

| Self-importance of moral identity (SIMI) | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.71 |

| Egocentric kindness × SIMI | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.27 |

| Social/normative kindness × SIMI | 0.09 | 0.13 | −0.16 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Extrinsically motivated kindness × SIMI | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.02 |

| Authentic kindness × SIMI | −0.43 | 0.16 | −0.74 | −0.12 | −0.24 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russo, C.; Zagrean, I.; Cavagnis, L.; Cristalli, S.; Valtulini, V.; Danioni, F.; Barni, D. The Relationship Between Kindness and Transgressive Behaviors in Adolescence: The Moderating Role of Self-Importance of Moral Identity. Adolescents 2025, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030040

Russo C, Zagrean I, Cavagnis L, Cristalli S, Valtulini V, Danioni F, Barni D. The Relationship Between Kindness and Transgressive Behaviors in Adolescence: The Moderating Role of Self-Importance of Moral Identity. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusso, Claudia, Ioana Zagrean, Lucrezia Cavagnis, Sara Cristalli, Valentina Valtulini, Francesca Danioni, and Daniela Barni. 2025. "The Relationship Between Kindness and Transgressive Behaviors in Adolescence: The Moderating Role of Self-Importance of Moral Identity" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030040

APA StyleRusso, C., Zagrean, I., Cavagnis, L., Cristalli, S., Valtulini, V., Danioni, F., & Barni, D. (2025). The Relationship Between Kindness and Transgressive Behaviors in Adolescence: The Moderating Role of Self-Importance of Moral Identity. Adolescents, 5(3), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030040