Unheard and Unseen: A Systematic Literature Review of Emotional Abuse Among Indian Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

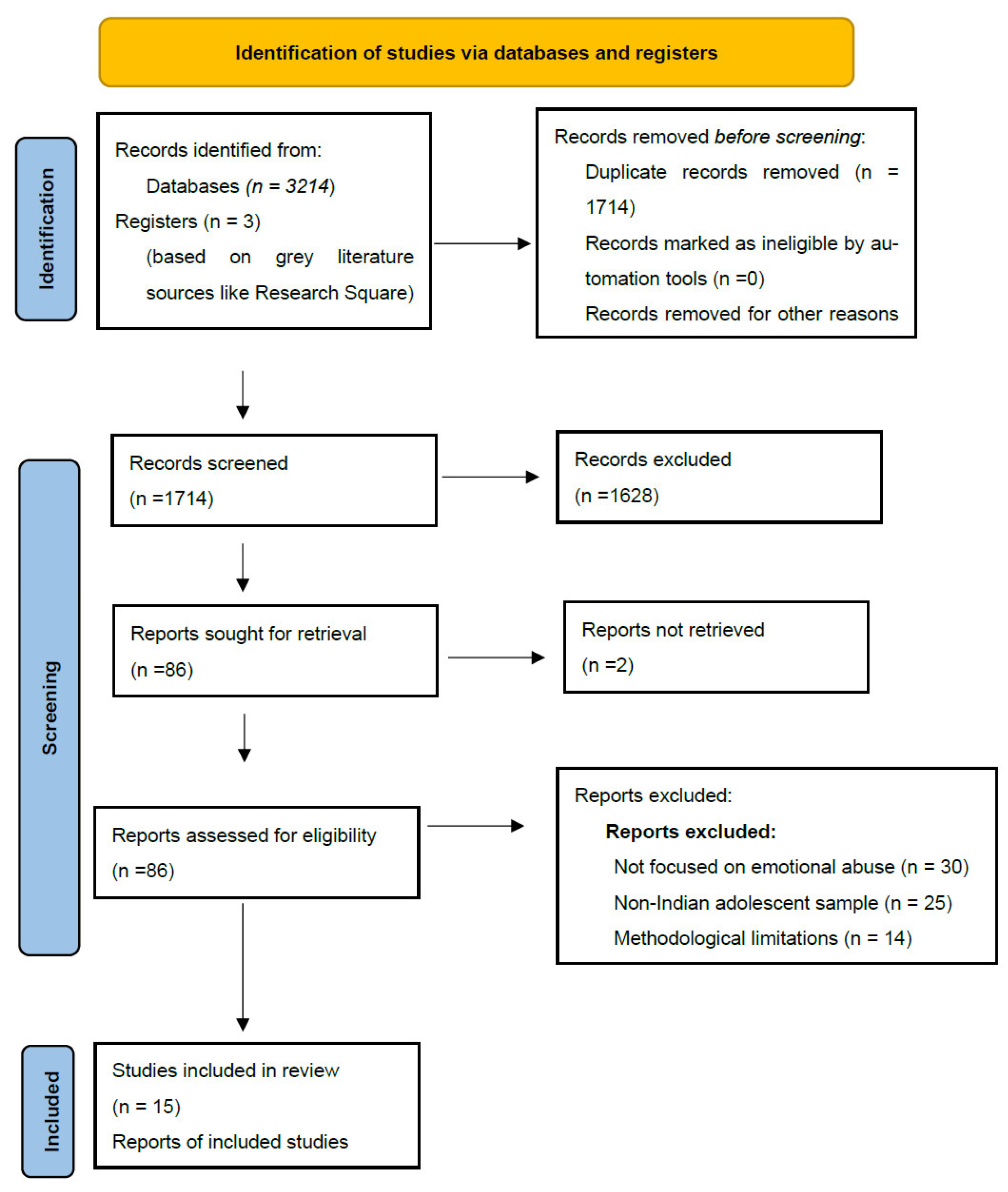

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Descriptive Characteristics

3.3. Thematic Synthesis

- Suppressed Emotionality and Internalized Blame

- 2.

- Culturally Patterned Gendered Abuse

- 3.

- Authority-Legitimized Abuse in Families and Schools

- 4.

- Coping Through Withdrawal and Creative Expression

- 5.

- Invisibility and the Absence of Systemic Support

| Study | Method | Sample Characteristics | Setting | Primary Research Question | Main Finding Related to Emotional Abuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al. (2023) [12] | SEM analysis, questionnaires | 571 school students (Kerala) | Schools | How does emotional abuse affect students’ mental health, and what is the role of family environment? | Emotional abuse significantly predicted depression; family environment mediated this relationship. |

| Sriram and Vasudha (2023) [25] | Cross-sectional, online survey | 90 young adults (18–25) | India | How do parental behaviors during adolescence relate to emotional competence and post-traumatic growth? | Emotional abuse was not significantly associated with emotional competence or PTG. |

| Kothapalli et al. (2023) [26] | Pre-post intervention study | 461 health students | Colleges | What is the effect of an awareness intervention on emotional abuse-related symptoms? | Reported decrease in depression and anxiety post-intervention related to emotional abuse awareness. |

| Kaur et al. (2024) [17] | Mixed methods (survey and interview) | Individuals aged 16–30 in romantic relationships | Urban settings | How is emotional abuse manifested in Indian dating relationships? | Restrictive emotional control (e.g., gaslighting) was common and linked to anxiety and depression. |

| Daral et al. (2016) [21] | Cross-sectional school-based survey | 1060 adolescent girls (13–19) | Schools (Delhi) | What is the prevalence of emotional abuse among adolescent girls and its determinants? | High prevalence of verbal/emotional abuse by mothers; linked to family conflict and education level. |

| Bhilwar et al. (2015) [27] | Stratified random sampling; questionnaires | 936 college students | Colleges | What are the correlates of emotional abuse in Indian adolescents? | Verbal abuse and emotional humiliation (e.g., appearance shaming) were commonly reported. |

| Damodaran, Raphael and Paul (2014) [20] | MHI and CECA-Q2 | 211 undergraduate students | Colleges (Kerala) | What is the relationship between maternal psychological abuse and adolescent mental health? | Conditional affection and blame from mothers associated with poor mental health outcomes. |

| Pandey et al. (2020) [13] | JVQ, SDQ, clinical interviews | 132 adolescents with child labor history | Urban community centers | What are the mental health risks of child labor, including emotional abuse? | Emotional abuse from employers/families contributed to psychiatric symptoms. |

| Trivedi et al. (2023) [22] | Mixed methods (ACE questionnaire + interviews) | 600+ adults (PTSD-positive) | Clinics | How does childhood emotional abuse relate to adult trauma symptoms? | Emotional abuse linked to PTSD symptoms; abuse by teachers and parents identified. |

| Waseem et al. (2024) [16] | In-depth interviews, NVivo analysis | 20 adolescents (13–19) | Urban schools (Aligarh) | What are the lived experiences of emotional abuse in Indian adolescents? | Gendered abuse, academic shaming, and colorism deeply impacted self-concept and coping. |

| Nesheen and Alam (2015) [9] | Thematic review | Adolescents (literature-based) | Literature | What parental behaviors contribute to adolescent aggression and low self-esteem? | Emotional abuse such as neglect and humiliation linked to aggression and low self-worth. |

| Kourti et al. (2021) [24] | Systematic review (32 studies) | Global sample (includes India) | Multinational | How did domestic violence, including emotional abuse, affect adolescents during COVID-19? | Caregiver verbal/emotional abuse increased during lockdown; led to distress and withdrawal. |

| Deepa K. Damodaran et al. (2014) [20] | Psychological abuse scale, MHI | 200+ Indian youth (18–24) | Mixed settings | How prevalent is parental psychological abuse, and how does it affect mental health? | Parental emotional neglect and verbal aggression correlated with poor psychological wellbeing. |

| Alam and Nesheen (2015) [10] | Thematic analysis | Adolescents in urban and semi-urban India | Mixed | What is the impact of fear-based parenting and humiliation on adolescents? | Persistent comparison and fear-based discipline led to emotional instability and peer withdrawal. |

| Firdous and Alam (2019) [16] | Quantitative survey | School-going adolescents | Urban schools | How does authoritarian parenting relate to emotional outcomes in adolescents? | Emotional abuse tied to emotional regulation issues and poor adjustment. |

| Study | Definition of Emotional Abuse | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al. (2023) [12] | Emotional abuse defined as persistent criticism, verbal aggression, rejection | Depression, happiness index, family environment as mediator |

| Sriram and Vasudha (2023) [25] | Emotional abuse operationalized via retrospective self-report on parental behavior | Emotional competence, post-traumatic growth (PTG) |

| Kothapalli et al. (2023) [26] | Abuse included verbal insults, psychological pressure from caregivers | Depression and anxiety (pre-post intervention impact) |

| Kaur et al. (2024) [17] | Restrictive emotional control in romantic relationships (e.g., gaslighting, emotional manipulation) | Anxiety, depression, relationship satisfaction |

| Daral et al. (2016) [21] | Verbal abuse and emotional neglect from parents, especially mothers | Reported abuse frequency, parental conflict, education levels |

| Bhilwar et al. (2015) [27] | Mockery, derogatory comments about appearance or intelligence | Prevalence of verbal abuse, perceived emotional harm |

| Damodaran, Raphael and Paul (2014) [20] | Maternal psychological abuse, including conditional affection and blame | Mental Health Inventory (MHI), CECA-Q2 |

| Pandey et al. (2020) [13] | Emotional abuse from employers and community (extra-familial) | Psychiatric symptoms, mental health risks (JVQ, SDQ) |

| Trivedi et al. (2023) [22] | Emotional abuse identified through ACE criteria; linked to PTSD | ACE scores, PTSD diagnosis, trauma history |

| Waseem et al. (2024) [16] | Gender-based abuse, academic shaming, and colorism-related insults | Distorted self-concept, coping strategies, resilience |

| Nesheen and Alam (2015) [9] | General emotional maltreatment including shaming and neglect | Aggression, suicidality, academic underperformance |

| Kourti et al. (2021) [24] | Verbal/emotional abuse during COVID-19 lockdowns by caregivers | Exposure to domestic violence, reporting rates, invisibility |

| Deepa K. Damodaran et al. (2014) [20] | Parental verbal aggression and emotional neglect | Poor mental health outcomes via standardized inventories |

| Alam and Nesheen (2015) [10] | Persistent humiliation, comparison, fear-based parenting | Emotional instability, peer withdrawal, self-worth |

| Firdous and Alam (2019) [16] | Authoritarian parenting involving rejection and shaming | Adolescent adjustment, emotional regulation difficulties |

| Theme | Gendered Aspects | Cultural Influences | Supporting Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suppressed Emotionality and Internalized Blame | Boys discouraged from showing vulnerability; girls mocked for emotional sensitivity and blamed for conflict | Emotional restraint and family honor prioritized over personal expression | Waseem et al. (2024), Kumar et al. (2023), Bhilwar et al. (2015) [12,16,27] |

| Culturally Patterned Gendered Abuse | Girls shamed for autonomy/appearance; boys punished for emotional expression | Patriarchal and honor-based norms reinforce emotional control | Kaur et al. (2024), Firdous and Alam (2019), Deepa K. Damodaran et al. (2014) [16,17,20] |

| Authority-Legitimized Abuse in Families and Schools | Both genders affected by rationalized abuse from elders and teachers | Hierarchical family and educational systems normalize verbal and emotional abuse | Trivedi et al. (2023), Daral et al. (2016), Nesheen and Alam (2015) [9,21,22] |

| Coping Through Withdrawal and Creative Expression | Girls journal or express through art; boys withdraw or numb emotions | Emotional expression is not supported within families or institutions | Waseem et al. (2024), Kaur et al. (2024), Damodaran, Raphael and Paul (2014) [16,17,20] |

| Invisibility and the Absence of Systemic Support | Both genders feel ignored; boys less likely to seek help | Emotional abuse rarely recognized or addressed in schools or clinics | Kourti et al. (2021), Sriram and Vasudha (2023), Kumar et al. (2023) [12,24,25] |

4. Discussion

- Ecological Context of Emotional Abuse in Adolescence

- Cross-Cultural Parallels in Collectivist Societies

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, J.J. Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: A Cultural Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, J.; Guttmann, E.; Seeley, J.W. The Psychologically Battered Child: Strategies for Identification, Assessment, and Intervention; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; Available online: https://archive.org/details/psychologicallyb0000garb (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- O’Hagan, K. Emotional and psychological abuse: Problems of definition. Child Abus. Negl. 1993, 17, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, B.; Becker-Lausen, E. The measurement of psychological maltreatment: Early data on the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale. Child Abus. Negl. 1995, 19, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez, E.; Estévez, J.F.; Segura, L.; Suárez, C. The Influence of Bullying and Cyberbullying in the Psychological Adjustment of Victims and Aggressors in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwairy, M. Parental Inconsistency: A Third Cross-Cultural Research on Parenting and Psychological Adjustment of Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 539–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickox, L.; Furnell, J. Psychological maltreatment of children in Indian families: A cultural perspective. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 16, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.; Nesheen, F. A study of perceived parental behavior and its impact on self-esteem and aggression among adolescents. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2015, 2, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshen, N.; Alam, S. Emotional abuse and its psychological consequences among adolescents. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2015, 7, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent flourishing: A moderated mediation model. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Deb, S.; Bhagyalakshmi, K.C. Impact of abuse on mental health and happiness among students: Mediating role of family environment. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2023, 19, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.R.P.; Bansal, S.; Benny, A. Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem among Adolescents: Role of Parenting Style. Indian J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 3, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan Tığrak, T.; Kulak Kayıkcı, M.E.; Kirazlı, M.Ç.; Tığrak, A. Emotional and behavioural problems of children and adolescents who stutter: Comparison with typically developing peers. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2021, 46, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldbeck, L.; Muche, R.; Sachser, C.; Tutus, D.; Rosner, R. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Eight German Mental Health Clinics. Psychother. Psychosom. 2016, 85, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, A.; Firdous, N. Emotional abuse among Indian adolescents: Effects on self-concept, resilience, and the role of cultural and societal pressures. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Agrawal, M.; Thakur, S. Examining emotional abuse in the context of urban Indian dating relationships. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2024, 12, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, E.; De Caroli, M. Relationships between resilience, self-concept, and coping strategies in adolescence. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 2292–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F. Emotional abuse and depression among adolescents: The mediating role of resilience. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, D.K.; Raphael, L.; Paul, S. Life skills training and psychological well-being of institutionalized adolescents. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Invent. 2014, 3, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Daral, S.; Khokhar, A.; Pradhan, S. Prevalence and determinants of child abuse among school children in Delhi. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2016, 62, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, K.; Sharma, M.; Das, S. Teachers’ emotional maltreatment and its psychological impact: A student perspective. J. Sch. Psychol. India 2023, 14, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Afreen, A.; Alam, S. Impact of emotional abuse on adjustment. IAHRW Int. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Kourti, M.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 23, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, R.; Vasudha, M. Cultural silence and adolescent distress: A qualitative study of emotional abuse. J. Indian Psychol. 2023, 9, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kothapalli, R.; Singh, A.; Sharma, P. Coping mechanisms among emotionally abused adolescents: A qualitative inquiry. Indian J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bhilwar, M.; Srivastava, A.; Gupta, S. Emotional abuse in Indian adolescents: Prevalence and correlates. Indian J. Youth Stud. 2015, 3, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Niaz, U. Violence against women in South Asian countries. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2003, 6, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudstra, M.J.; Emmen, R.A.G.; Alink, L.R.A.; Wang, L.; Branger, M.C.E.; Mesman, J. Attitudes about child maltreatment in China and the Netherlands. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 112, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Bristol. Seen but Not Heard: Addressing the Silent Epidemic of Child Maltreatment in India. PolicyBristol. 2021. Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/policybristol/policy-briefings/child-maltreatment-india/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Humanium. Verbal Abuse Against Children in the Middle East. 2021. Available online: https://www.humanium.org/en/verbal-abuse-against-children-in-the-middle-east/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Nadeem, A.; Bornstein, M.H. Culture, honor, and silence: The social construction of emotional abuse. J. Fam. Psychol. 2023, 37, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kağıtçıbaşı, Ç. Family, Self, and Human Development Across Cultures: Theory and Applications, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, D.; Bornstein, M.H. Cross-cultural comparisons of parenting. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2008, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, L.N. Cultural collectivism, intimate partner violence, and women’s mental health in South Asia. J. Soc. Issues 2023, 79, 45–67. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10098113/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waseem, A.; Firdous, N. Unheard and Unseen: A Systematic Literature Review of Emotional Abuse Among Indian Adolescents. Adolescents 2025, 5, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030041

Waseem A, Firdous N. Unheard and Unseen: A Systematic Literature Review of Emotional Abuse Among Indian Adolescents. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaseem, Afreen, and Naila Firdous. 2025. "Unheard and Unseen: A Systematic Literature Review of Emotional Abuse Among Indian Adolescents" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030041

APA StyleWaseem, A., & Firdous, N. (2025). Unheard and Unseen: A Systematic Literature Review of Emotional Abuse Among Indian Adolescents. Adolescents, 5(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030041