1. Introduction

School bullying is a pervasive public health issue that has garnered growing attention from scholars across various disciplines [

1]. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), one in three children globally report experiences of being bullied [

2]. Bullying in schools manifests in different ways, including physical, verbal, and social aggression. These behaviors can occur directly (e.g., face-to-face interactions) or indirectly (e.g., spreading rumors). With the advent of technology, bullying has also expanded into digital environments through cyberbullying [

3]. This review focuses specifically on school-based in-person bullying, defined as bullying behaviors occurring within school environments among individuals aged 4 to 18 years. As a multifaceted social phenomenon, school bullying involves roles that students may occupy as bullies, victims, or bully–victims.

Understanding school bullying requires recognizing two critical elements of its dynamics: The first is its aggressive nature, which is perpetuated from a position of power. Children who bully typically hold more power than their victims, deriving this power from physical dominance (e.g., size or strength), social advantages (e.g., higher social status or a senior position within a peer group), or systemic inequities (e.g., non-disabled children targeting those with disabilities). The second element is the repetitive nature of bullying. Each incident reinforces the existing power imbalance: as bullies repeatedly inflict harm and distress, their dominance grows, while victims experience a corresponding loss of power in the relationship. These dynamics solidify over time, entrenching the roles of aggressors and victims, and exacerbating the adverse effects of bullying.

Addressing bullying is imperative due to its profound impact on the health, social well-being, and academic performance of students [

4,

5,

6,

7] The health consequences of bullying are extensive, affecting both physical and mental well-being. Victimized children often experience increased feelings of loneliness and physical injuries [

8]. Research has also demonstrated that children who experience frequent bullying are at significantly greater risk for contemplating or attempting suicide compared to their non-bullied peers [

9,

10]. Additionally, bullying is associated with higher rates of substance use and lower self-reported life satisfaction. Bullying significantly impacts the educational experience, fostering an atmosphere of anxiety, fear, and insecurity that hinders effective learning. Victimized students demonstrate reduced engagement with their education, lower academic performance, and diminished test scores compared to their peers [

11]. Furthermore, frequent exposure to bullying is correlated with an increased desire to drop out of school [

12]. These outcomes highlight the urgent need for effective interventions to mitigate the multifaceted impacts of bullying on students’ lives.

In response to the significant health, social, and academic challenges experienced by both bullies and victimized students, numerous school-based bullying prevention programs have been developed across various disciplines [

4]. Since the pioneering research on bullying in the 1970s [

13], scholarly efforts in this field have expanded exponentially, particularly within the disciplines of psychology and education. As the body of evidence has grown, schools have increasingly adopted anti-bullying policies and programs aimed at fostering a safe and supportive environment for all students. Research indicates that many of these school-based anti-bullying programs demonstrate effectiveness. Findings from a meta-analysis revealed that intervention programs can reduce bullying perpetration (i.e., measurable decrease in the frequency, severity, and persistence of bullying behaviors) in schools by 20 percent and bullying victimization by approximately 16 percent [

14].

Whole-school approaches [

15] and multi-tiered systems of support (MTSSs) [

16] have emerged as foundational frameworks guiding the development and implementation of contemporary anti-bullying interventions. Whole-school approaches prioritize the engagement of all members of the school community, including students, staff, families, and community partners, in cultivating a positive and inclusive school culture that actively discourages bullying behavior. These frameworks emphasize prevention, capacity building, and consistent reinforcement of prosocial norms across settings. Complementing this, the MTSS framework offers a structured, tiered model of intervention delivery that matches the intensity of support to students’ specific needs [

17]. Tier 1 (universal) interventions seek to promote positive behavior and inclusive environments for all students. These school-wide and universal anti-bullying programs aim to create a positive school environment where respect is encouraged and where bullying is not allowed. Tier 2 (targeted) supports are designed for students at increased risk of involvement in bullying. Students who are perceived as different, such as those who are overweight, gay, bisexual, transgender, or children with disabilities, often face identity-based stigma that influences their bullying experiences. Unlike their non-stigmatized peers, these students are often targeted due to inherent aspects of their identity. This stigma manifests through repeated verbal harassment (e.g., name-calling, slurs), social exclusion, physical aggression, and systemic discrimination within the school environment. As a result, their experiences of bullying are often more frequent, severe, and persistent, rooted in prejudice and societal stereotypes rather than isolated peer conflicts [

18]. Interventions in this tier are usually carried out in classroom settings and small groups. Tier 3 (intensive) interventions focus on specific individuals and deliver individualized strategies for those with the most significant needs. This tier is implemented after bullying has been seen or heard and consists of intensive and individualized interventions. Together, these frameworks support a comprehensive and scalable response to bullying that aligns with occupational therapy’s focus on participation, environmental modification, and skill development.

Occupational therapy practitioners offer a unique and underutilized perspective in school-based anti-bullying efforts. Their training emphasizes supporting children’s participation in daily routines and social environments through the therapeutic use of meaningful activities, known in the field as occupations. While many bullying interventions focus on behavioral changes or discipline, occupational therapy focuses on enabling students to strengthen their friendships, coping strategies, and resilience through activity-based strategies. Occupational therapy practitioners are also well equipped to address the needs of students with disabilities or mental health conditions, who are often at greater risk of bullying victimization. As such, occupational therapy practitioners can complement the work of teachers, counselors, and psychologists by providing developmentally appropriate, inclusive, and participation-driven interventions. Unlike many traditional approaches that focus solely on behavioral management or counseling, occupational therapy practitioners approach bullying through the lens of participation and engagement in meaningful activities. They are trained to assess students’ strengths and the environmental barriers that affect students’ ability to participate in school. This holistic, function-based perspective allows occupational therapy practitioners to deliver interventions that are developmentally appropriate, inclusive of students with disabilities, and grounded in positive mental health promotion. Furthermore, by framing anti-bullying strategies as occupation-based interventions, occupational therapy practitioners can enhance the programs’ effectiveness by focusing not only on skill acquisition but also on promoting engagement, emotional well-being, identity formation, and meaningful social participation. This approach allows for greater individualization and responsiveness to students’ diverse strengths, needs, and preferences.

Given the training that occupational therapy practitioners receive in mental health, social participation, and child development, occupational therapy practitioners have the skills to be part of the interprofessional team that addresses bullying using proven, evidence-based interventions. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) [

19] recognizes the need for occupational therapy’s involvement to address bullying. However, addressing bullying is not yet an established part of the work carried out by occupational therapy practitioners. A study of school-based occupational therapy practitioners showed that even though occupational therapy practitioners recognized that bullying was occurring in their schools, they reported a lack of knowledge and training, including evidence-based interventions, as key barriers to why they were not taking on a role [

16]. Furthermore, despite the vast amount of research conducted on school bullying, there is a dearth of published literature on interventions for occupational therapy practitioners to use [

20]. Thus, occupational therapy practitioners need to be equipped with occupation-based interventions to address the phenomenon of bullying in schools, to effectively combat bullying as part of the interprofessional team and advocate for the role of occupational therapy.

To date, there is no compendium of occupation-based interventions to address school bullying. This lack of synthesis of the research contributes to the underuse of bullying interventions in school-based occupational therapy practice. Prior systematic reviews [

4,

21] have examined the effectiveness of bullying prevention programs, often focusing on overall reduction rates in perpetration or victimization, and emphasizing programmatic frameworks like whole-school approaches. However, these reviews analyzed interventions from the perspectives of psychology, education, or public health, without categorizing the interventions based on occupations (i.e., the activities used) or examining their relevance to occupational therapy practice. Our systematic review expands on the existing literature by examining interventions through an occupational therapy lens. Specifically, this review analyzes whether the interventions incorporate meaningful, occupation-based activities that align with occupational therapy’s focus on promoting participation, social engagement, and emotional well-being. By categorizing the interventions by type of occupation used and aligning them with a multi-tiered framework, this review identifies evidence-based strategies that occupational therapy practitioners can integrate into their practice. Thus, this review contributes a novel, discipline-specific analysis to the existing body of research on school-based bullying interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, to ensure a rigorous and transparent approach to the identification, selection, and synthesis of relevant studies [

22]. No study protocol was registered.

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

To obtain evidence regarding occupation-based interventions to address school bullying, we identified studies published up to June 2024 using a systematic search across PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Proquest Central, and Web of Science. The search strategy included combinations of multiple keywords and search terms for school, bullying, and interventions and was developed with the help of a university librarian. Search terms were combined using Boolean operators (i.e., “OR”, “AND”) to increase both the specificity (i.e., the ability to identify relevant papers) and sensitivity (i.e., the ability not to identify many irrelevant articles) of the search. Relevant journals (i.e.,

Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Aggression, and Violent Behavior;

Journal of School Violence;

Journal of School Health; and

International Journal of School Bullying Prevention) were hand-searched. The inclusion criteria included (1) a school bullying intervention paper, (2) an occupation-based intervention within the scope of practice of occupational therapy, (3) written in English, and (4) published in a peer-reviewed journal. Any type of intervention study was included (qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed-methods studies). To determine if an intervention was occupation-based, we used the following description: “Embedded in activities and within the domain of OT, although it did not have to be a common OT intervention or administered by an OT or OTA” [

23] (p. 122). In this review, no historical cut-off date was imposed, in order to capture the full breadth and evolution of research on the topic. The exclusion criteria included studies focused solely on cyberbullying outside of the school context, studies conducted on bullying interventions for adults (>18 years old), published studies not in the English language, and studies not published in peer-reviewed journals (i.e., theses and dissertations).

2.2. Study Selection

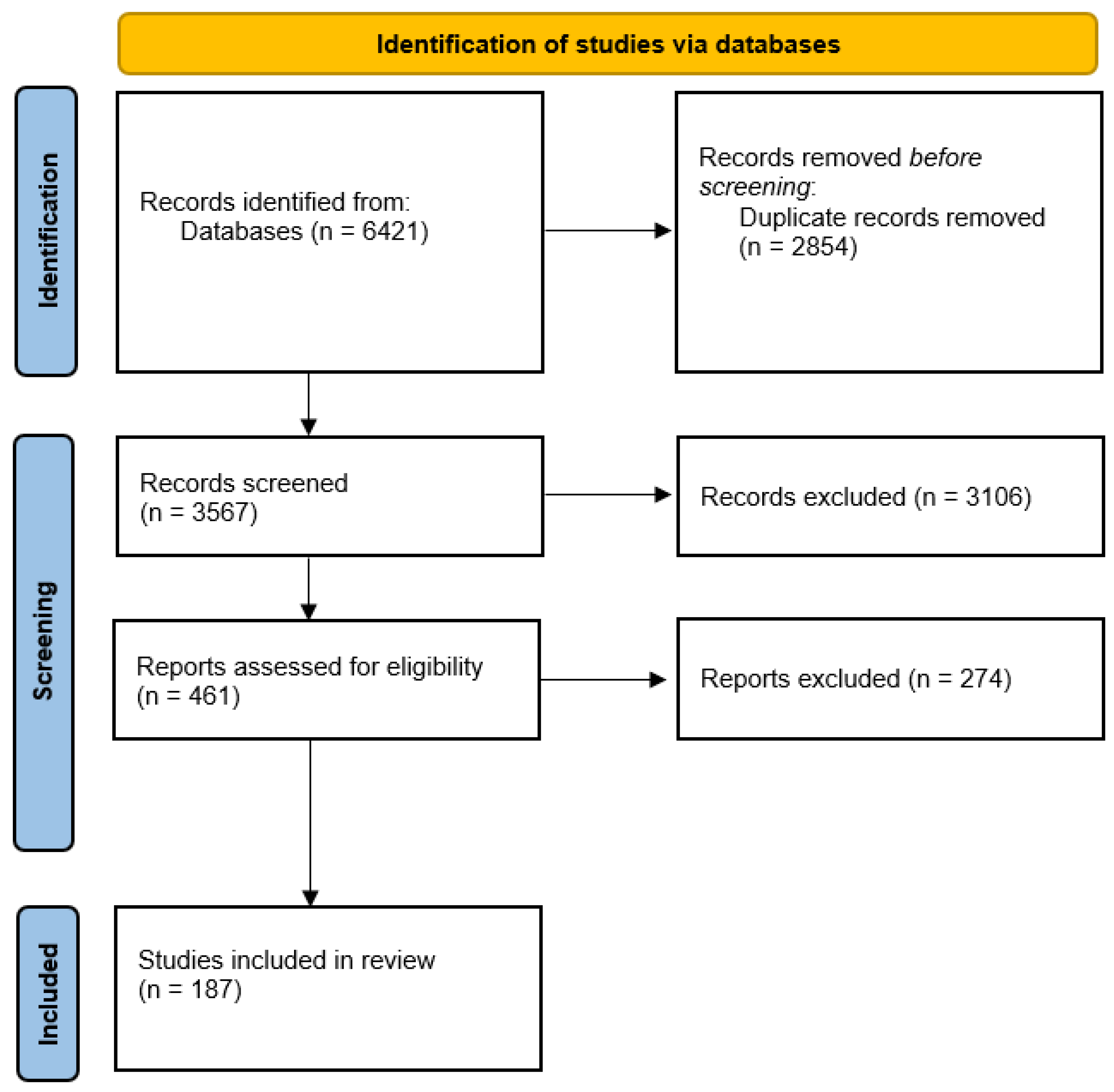

We used Covidence, an online software platform, for evidence synthesis. First, we uploaded the search results, and duplicates were removed. Two members of the research team screened all of the abstracts (n = 3567) for inclusion. A total of 3106 studies were excluded at this stage because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or met the exclusion criteria. Then, each full-text article (n = 461) was read to determine whether the article met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following a review of the remaining articles’ full texts against the inclusion criteria, 187 studies were included in the final sample. The main reason for exclusion was that the intervention was not occupation-based (i.e., not embedded in activities). The screening process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (see

Figure 1). Any disagreement was resolved by a third member of the research team at each step of study selection.

2.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

Different tools were utilized for the quantitative, mixed-methods, and qualitative studies, reflecting the nature of each study design. For quantitative studies, we used the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB) Tool. We assessed the methodological quality of qualitative studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist, and mixed-methods studies were assessed using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [

24].

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Using a Microsoft Excel table, the following data were extracted from each study: study characteristics (year of publication, study country, study design, level of evidence), author characteristics (their country, area of discipline), participant characteristics (age or grade of participants), intervention characteristics (occupation used, dosage, duration of treatment), what the authors considered to be the main theoretical or active components of the interventions, aim(s) of the study, outcome measures, results, and inclusion of stigmatized groups (e.g., children with disabilities).

A meta-analysis was not conducted because of the variation in outcomes and study designs. We employed narrative synthesis to analyze and integrate findings across the included studies because of the heterogeneity of the included studies, focusing on the tier of intervention and the activities used. The occupations incorporated into the interventions were systematically identified based on the descriptions of the intervention activities provided in the included studies. Each activity was assessed to determine whether it involved meaningful, purposeful engagement aligned with occupational therapy practice. Activities were then categorized into groups based on their core characteristics: social participation activities (e.g., friendship-building, social skills training), play-based occupations (e.g., games, puppetry, virtual reality experiences), school-related activities (e.g., journaling, reading comprehension tasks), arts-based occupations (e.g., crafts, drama, filmmaking), and sports and physical activities (e.g., martial arts, self-defense). This categorization was grounded in occupational therapy practice models that emphasize participation in diverse, meaningful activities to support health and development. This categorization provided a structured framework for analyzing how different types of meaningful activities were integrated into anti-bullying interventions across the three tiers.

The strength of evidence was determined following the guidelines outlined by the AOTA [

25] and categorized as follows: strong evidence: at least two well-designed Level 1 studies; moderate evidence: at least one high-quality Level 1 study or multiple studies of moderate quality (Level 2 or 3); and low evidence: a small number of lower-level studies.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

The search retrieved 187 studies on interventions to address school bullying. The studies were published between 1977 and 2024 and, in order of frequency, were undertaken in the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, Australia, Canada, Germany, Portugal Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Norway, Austria, Brazil, Taiwan, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, New Zealand, Romania, South Africa, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Iran, Ireland, Colombia, Israel, Japan, Kosovo, Malaysia, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Zimbabwe. The majority of the authors identified as scholars from the fields of psychology (126), health (33), and education (28), with the remainder from such fields as computer science, criminology, and social work. The review included 138 quantitative studies, of which 51 were Level 1b studies (i.e., well-designed randomized controlled trials [RCTs]), 56 were Level 2b studies (lower-quality RCTs or two-group nonrandomized studies), and 37 were Level 3b studies (i.e., retrospective case–control studies; one-group, nonrandomized pre–post-test studies; or cohort studies), while 31 were mixed-methods studies, and 18 were qualitative research studies. A variety of outcomes were assessed, including students’ attitudes towards bullying and cyberbullying, their level of victimization, their involvement in bullying, their willingness to intervene, self-assertive efficacy to resist peer pressure for aggressive behavior, emotional recognition and physical aggression, verbal/relational bullying perpetration and peer victimization, homophobic perpetration and victimization, traditional aggression and victimization, self-reported bullying and victimization, and relational aggression and victimization.

The studies targeted students aged 5 to 18. Of these, 59 studies included elementary-school students, 40 studies included middle-school students, 37 studies included high-school students, 14 included middle- and high-school students, 24 included elementary-, middle-, and high-school students, and 13 studies did not include the participants’ specific school grades. Of the total studies, 174 included non-disabled students. Only 13 studies focused specifically on bullying interventions for students with disabilities as participants. In these studies, the reported impairments of students included Asperger syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, Down syndrome, intellectual disabilities, hearing impairment, visual impairment, social communication disorder, and epilepsy.

3.2. Tier of Bullying Intervention

This systematic review identified and categorized anti-bullying interventions into three tiers, reflecting a multi-tiered approach for occupational therapy practitioners to address bullying within school settings.

3.2.1. Tier 1: Universal Interventions

Tier 1 interventions aimed to foster a positive and inclusive school climate by implementing school-wide prevention strategies. These interventions typically focused on fostering social–emotional skills, building emotional intelligence and empathy, and promoting respectful peer interactions. These interventions were often grounded in the Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) framework. Common activities included structured classroom curricula, emotion regulation exercises, and peer collaboration projects. The classroom-based curricula combined lessons on bullying awareness with strategies for emotional regulation and conflict resolution [

26,

27]. These interventions were found to raise awareness about bullying among students, staff, and faculty, and to cultivate a positive and inclusive school environment. For instance, Li et al. [

28] implemented the Positive Action program, which combined lessons on emotional regulation, conflict resolution, and positive decision-making, resulting in significant reductions in bullying behaviors and improved school connectedness. Overall, the strength of evidence for Tier 1 interventions was strong, with multiple high-quality randomized controlled trials demonstrating consistent and substantial positive outcomes. Tier 1 interventions, particularly those following the SEL framework, were found to be effective due to their focus on fostering positive school climates and engaging multiple stakeholders, including students, parents, and educators. While Tier 1 interventions aim to affect the overall school environment, Tier 2 interventions focus on supporting students at higher risk of bullying involvement.

3.2.2. Tier 2: Targeted Interventions

Tier 2 interventions aimed to support students identified as being at moderate risk of bullying involvement, either as victims or perpetrators. These interventions typically focused on enhancing peer relationships, building social skills, and empowering students to navigate complex social dynamics. Common activities included peer mentoring programs, small-group social skills training [

29], and friendship coaching sessions. For instance, King et al. [

30] implemented a multidimensional peer mentoring program that paired at-risk students with trained mentors, resulting in increased self-esteem and improved school connectedness. Similarly, Fox and Boulton [

31] utilized small-group social skills workshops to enhance assertiveness and reduce vulnerability to bullying. Friendship coaching was also utilized to help children build and sustain peer relationships [

32]. Peer involvement played a prominent role in several interventions at this tier, aiming to empower students to actively combat bullying within their communities. Peer-led activities included mentoring programs, where older students supported peers experiencing bullying, and peer involvement initiatives designed to promote collaborative efforts to prevent and respond to bullying [

33]. By fostering positive peer relationships, these activities sought to create a culture of mutual support and accountability among students. The strength of evidence for Tier 2 interventions was moderate, with several studies demonstrating positive outcomes, although variations in intervention delivery and measurement limited the generalizability of the findings. While Tier 2 interventions offer crucial support for at-risk students, Tier 3 interventions focus on individualized responses for the students most severely affected by bullying.

3.2.3. Tier 3: Intensive Interventions

Tier 3 interventions targeted students who were at high risk of bullying involvement, particularly those experiencing significant and chronic victimization. These interventions typically emphasized individualized, therapeutic support to build coping skills, resilience, and problem-solving abilities. Common activities included one-on-one counseling, individualized social skills training, and family engagement programs that provided guidance and resources to the families of students involved in bullying to address issues collaboratively [

34]. For example, Fekkes et al. [

35] implemented personalized social problem-solving sessions for students reporting frequent victimization, aiming to strengthen their coping strategies and social networks. Berry and Hunt [

36] developed an intervention program for anxious adolescents who were bullied to improve their emotional regulation and reduce bullying-related anxiety. Additionally, programs trained students to support their peers during bullying incidents and to act as effective bystanders [

37,

38]. The strength of evidence for Tier 3 interventions was low, largely due to the limited number of high-quality studies and the individualized nature of the interventions, which made broad outcomes difficult to generalize. These findings highlight the importance of integrating Tier 3 approaches within a larger, multi-tiered anti-bullying strategy to maximize their impact.

3.3. Nature of Occupations Incorporated

The review identified a range of occupations incorporated into anti-bullying programs, offering insights into strategies that occupational therapy practitioners can employ within school settings. The identified occupations reflect diverse approaches to fostering social interaction, engagement, and skill development among students. These occupations, derived from the described activities in the programs, are categorized below based on shared activities, as described in the above data synthesis section.

3.3.1. Social Participation Activities

The most frequently utilized occupations were social participation activities used in interventions to foster social participation. These activities, defined as those involving social interactions with family, friends, and peers to promote social interdependence [

39], were implemented within 103 of the interventions. Examples included friendship-building activities [

40], social skills training, role-playing [

31], and activities focused on developing interpersonal skills [

35]. These activities aimed to strengthen students’ empathy, understanding of differences, and abilities to build and maintain relationships, critical components in bullying prevention and intervention. Although role-playing inherently involves elements of imaginative play, for the purposes of this review, it was categorized under social participation activities, because the role-playing activities in the included studies were predominantly designed to build social skills, empathy, and interpersonal communication—core components of social participation—rather than for the intrinsic purpose of imaginative play or recreation. We recognize that there is overlap between role-playing, games, and play-based activities, and this categorization reflects the goals emphasized in the included studies.

3.3.2. Play-Based Occupations

Play-based activities constituted the second most common type of occupation, with 73 studies including these activities as part of their intervention. The programs incorporated a variety of games, such as board games for addressing social dynamics and promoting problem-solving skills [

41], virtual reality experiences [

42], and online computer games to explore and address bullying scenarios [

43]. Additionally, puppetry [

44] was used as an innovative and creative approach to encourage role-playing and emotional expression, helping students to explore social scenarios in a safe and controlled environment.

3.3.3. School-Related Occupations

A total of 21 interventions incorporated school-based activities, leveraging tasks commonly associated with academic settings to promote reflection and communication. These included journaling exercises to encourage self-reflection and emotional expression [

30], word-finding activities to enhance communication skills [

45], and reading-based tasks aimed at promoting empathy and understanding and designed to promote literacy and critical thinking while addressing bullying themes [

46].

3.3.4. Arts-Based Occupations

Creative occupations also played a significant role in anti-bullying programs, utilizing various forms of artistic expression to engage students and foster communication and emotional processing. In total, 33 studies incorporated art-based activities. These included, for example, crafts [

33], filmmaking [

47], drawing [

48], comic book creation [

45], and drama activities [

49] that allowed participants to express their thoughts and feelings creatively while developing empathy and collaboration skills through shared projects. These activities not only facilitated emotional expression but also empowered the participants to envision and rehearse prosocial behaviors in innovative and engaging ways.

3.3.5. Sports and Physical Activities

Sports-related occupations were implemented in 13 studies to enhance physical and emotional resilience among students. Martial arts [

50] and self-defense training [

51] emerged as the most used approaches in this category. These activities aimed to build confidence, self-discipline, and physical empowerment, equipping students with the skills and mindset to navigate challenging social situations effectively. These interventions were used not only to build confidence but also to provide students with tools to navigate and de-escalate challenging situations.

4. Discussion

Despite the alignment of many school anti-bullying interventions with occupational therapy practice, previous research indicates that occupational therapy practitioners are underutilized in this area, often citing a lack of knowledge as a key barrier. Practitioners may feel daunted by the misconception that they must independently develop and implement entirely new interventions; however, one step is to draw upon the current evidence base to incorporate interventions that fit within occupational therapy practice as they work collaboratively with school staff as part of an interprofessional team. This review addresses this gap by synthesizing evidence-based interventions that occupational therapy practitioners can incorporate into their school-based practice and guiding them in selecting the most effective approaches to implement. In total, 187 school bullying studies were found to have incorporated meaningful activities as an intervention modality, highlighting a strong role for occupational therapy practitioners to work with bullies, victims, and bully–victims.

While past systematic reviews primarily measured the overall effectiveness of anti-bullying programs, our review also explored the strength of evidence within a multi-tiered framework (Tiers 1, 2, and 3) that matches intervention intensity to student risk levels, a perspective that is highly relevant to occupational therapy’s involvement in school-based multi-tiered systems of support. The findings from this review align with those of previous reviews in recognizing the effectiveness of whole-school, universal interventions (Tier 1), which prioritize fostering a positive school climate [

21]. At the school-wide systems level, students’ mental health needs often go unrecognized, so interventions at this tier ensure that all students receive some level of support. These interventions are particularly impactful because they address bullying comprehensively by engaging students, staff, and parents, and they have been proven effective in other areas of school-based occupational therapy practice, including positive mental health promotion programs such as comfortable cafeterias, refreshing recess, or classroom strategies [

52]. Targeted interventions (Tier 2), including social skills training, peer mentoring, and friendship coaching, demonstrated moderate effectiveness. These interventions address at-risk populations, such as students with disabilities, bullies, and bully–victims, by equipping them with tools to navigate complex social interactions. Finally, intensive, individualized interventions (Tier 3) focusing on high-risk individuals, such as victimized students, were found to be less effective when implemented in isolation. Therefore, while individualized intervention may help a victimized student to develop coping strategies, it does not address the systemic peer dynamics or school-wide culture that perpetuate bullying. As a result, the student may continue to face hostile social environments even after intervention, highlighting the need for these as part of a broader, multi-tiered strategy. Previous studies [

16] have indicated that it is at this tier of intervention that occupational therapy practitioners have previously been most involved in anti-bullying efforts, which suggests a need for expanding the role of the profession to the other two tiers.

Beyond bullying interventions, occupational therapy practitioners have partnered with teachers and school staff to support students through a multi-tiered framework of intervention, including the use of the Response to Intervention (RTI) model [

53]. Therefore, taking a multi-tiered approach and being involved in interventions across tiers offers occupational therapy practitioners the opportunity to deliver a spectrum of services tailored to students with different levels of bullying risk while addressing their unique needs to promote inclusion and school participation.

This review identified a significant gap in anti-bullying initiatives targeting students with disabilities, underscoring the importance of ensuring that Tier 1 and Tier 2 interventions are inclusive. These interventions often fail to address critical factors contributing to violence against children with disabilities, such as disability-based stigma, despite their increased vulnerability to bullying victimization [

54]. This finding is consistent with other public health studies and previous reviews that found that children with disabilities are frequently excluded from research [

55]. Occupational therapy practitioners’ training in mental health, child development, and social participation uniquely equips them to address disability-based bullying, being valuable resources in research collaborations as interventions are developed and evaluated.

This review also highlights the diversity of occupations incorporated into anti-bullying programs. By categorizing interventions based on their core activities, this review provides occupational therapy practitioners with a selection of anti-bullying programs that may be chosen based on students’ identified preferred occupations and strengths. The incorporation of occupation-based activities across all tiers of intervention demonstrates their versatility in addressing the social and emotional challenges associated with bullying. Activities promoting social participation, such as friendship-building and social skills training, were particularly effective in fostering empathy, communication, and positive peer relationships. These outcomes align closely with occupational therapy practice, which focuses on enabling individuals to engage in meaningful and purposeful activities, and are supported by the AOTA, which has advocated for the role of occupational therapy in combating bullying, stating that occupational therapy practitioners can prevent bullying by promoting positive student interactions, encouraging participation in enjoyable occupations, teaching coping strategies, and fostering friendships [

19].

Play-based and arts-based interventions were also prominently used in interventions, leveraging creativity and innovation to engage students in exploring and addressing bullying dynamics. For example, the use of puppetry, virtual reality, and board games provided opportunities for role-playing and problem-solving, enabling the participants to practice social interactions in a safe and controlled environment. These activities not only addressed bullying behaviors but also enhanced students’ emotional regulation and resilience, key areas of focus for occupational therapy practitioners who work with students. Furthermore, the incorporation of play activities in school bullying interventions aligns with occupational therapy’s emphasis on the critical role of play in supporting children’s development, social skills, and overall well-being, making it a natural and effective approach within the profession’s scope.

The evidence reviewed here supports the integration of occupational therapy practitioners into school-based anti-bullying initiatives. By focusing on promoting participation in meaningful occupations, occupational therapy practitioners can address not only the behavioral aspects of bullying but also the underlying social–emotional competencies that enable sustained positive peer engagement. The activities identified across the interventions, including social participation exercises, play-based activities, creative arts, and physical engagement, align closely with core areas of occupational therapy practice. Occupational therapy practitioners are therefore uniquely positioned to utilize and adapt these meaningful activities to promote students’ emotional regulation, peer relationships, resilience, and overall school participation. Thus, the findings of this review provide an evidence base on which occupational therapy practitioners can draw to design or enhance occupation-based anti-bullying interventions within school settings. Occupational therapy’s holistic, client-centered approach uniquely complements educational and psychological interventions, filling a critical gap in current school bullying prevention efforts.

While this review supports the relevance of occupational therapy in anti-bullying efforts, integrating occupational therapy practitioners into school-based bully prevention teams poses both systemic and practical challenges that must be addressed to fully realize this potential. One of the most cited barriers is the limited awareness among school administrators and educators regarding the full scope of occupational therapy beyond fine motor skills and sensory integration [

16]. Anti-bullying initiatives are frequently viewed as falling solely under the purview of school counselors or psychologists, leading to occupational therapy being underutilized despite its relevance. This misperception can marginalize occupational therapy’s involvement in broader psychosocial and preventive initiatives, including bullying prevention. Additionally, many occupational therapy practitioners report inadequate pre-service or in-service training in mental health promotion and social–emotional learning frameworks, which are foundational to Tier 1 and Tier 2 anti-bullying efforts [

6]. Time constraints and high caseloads further restrict their capacity to participate in non-mandated programming, especially in under-resourced school districts where practitioners may be split across multiple schools. Practitioners are frequently working on a caseload model focused primarily on individualized services dictated by students’ Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), leaving little capacity for universal or preventive programming. In contrast, several facilitators can enable occupational therapy’s integration into anti-bullying systems. Schools that adopt whole-school or MTSS frameworks are more likely to embed occupational therapy within interdisciplinary teams addressing student well-being at multiple levels. When occupational therapy services are structured to include universal or group-based interventions (e.g., classroom-based social participation activities or SEL curricula), practitioners can extend their impact beyond traditional referral-based practice.

To address the identified barriers, occupational therapy practitioners would benefit from mentorship and access to professional development opportunities, including specific training provided through entry-level programs and continuing education courses, focusing on bullying interventions across all tiers of support. These learning opportunities would help ensure that future practitioners are equipped to address the critical issue of school bullying.

4.1. Limitations

As with all systematic reviews, this study has several limitations. One notable limitation is the potential omission of relevant studies due to inconsistent terminology, as some studies may have used alternative terms to describe program activities or occupations. Moreover, in several studies, the description of the intervention was insufficient to determine whether an occupation was used. Additionally, the global and interdisciplinary scope of the topic may have resulted in the exclusion of documents published in journals not covered by the electronic databases searched, or of those written in languages other than English. Finally, although an abundance of literature exists on school bullying programs, the majority of the studies did not explicitly address how the use of the occupations led to their outcomes, or whether different occupations led to better outcomes than others.

4.2. Future Research Directions

The vast majority of the interventions included in this review were developed and implemented by professionals outside the field of occupational therapy, such as psychologists, educators, and social workers. Moving forward, occupational therapy practitioners are well positioned to contribute their distinct expertise to transdisciplinary efforts that design, implement, and evaluate bullying interventions. Such integrated approaches, grounded in multiple disciplinary frameworks and involving the perspectives of students and families, are more likely to address the diverse needs of students and avoid the limitations of siloed interventions.

Despite widespread recognition that students with disabilities, LGBTQ+ youth, and students from historically underrepresented communities experience disproportionate rates of bullying, few studies in the current literature robustly address these intersecting identities. Future research must prioritize inclusive and culturally responsive intervention design that explicitly addresses stigma, discrimination, and structural inequities in school environments. Participatory action research involving students with disabilities and their families can ensure the relevance and responsiveness of this research. Moreover, researchers should examine how students’ intersecting identities influence their bullying experiences.