The (Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate System: (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Pentahydrate (Ribbons of Planar (H2O)6 Rings Fused with Planar (H2O)4 Rings) and (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Acetonitrile Solvate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Syntheses

2.2. Crystallography

3. Discussion

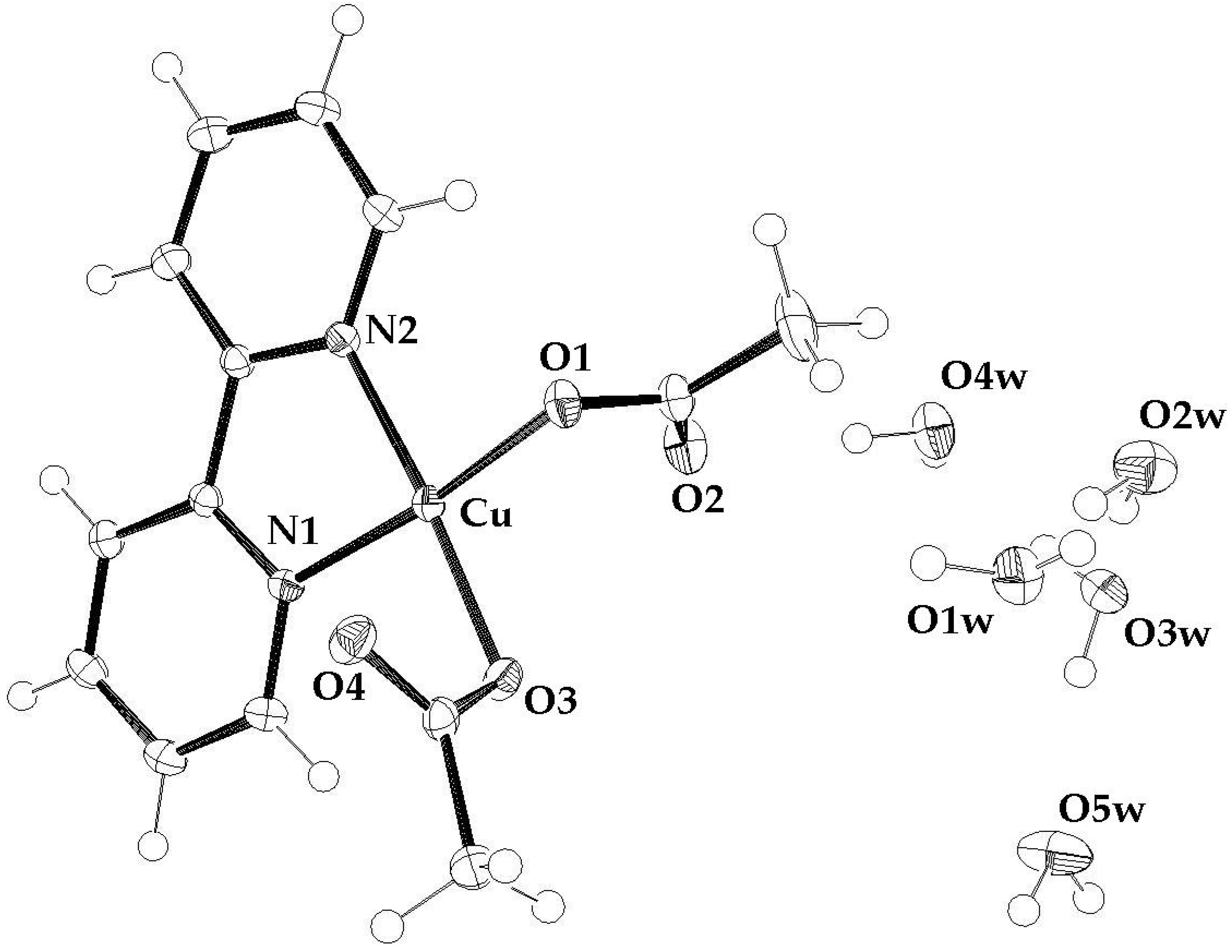

3.1. Water and the Crystal Structure of the Pentahydrate Compound 3

3.2. Non-Bonded Interactions

3.3. Infrared Spectrum of Phase 3

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Entzminger, P.D.; Cawker, N.C.; Graveson, A.N.; Erickson, A.N.; Valente, E.J.; Urnezius, E. Double Oxidative Dehalogenation of 2,5-Bis(diisopropylphosphoryl)-3,6-difluoro-1,4-hydroquinone leading to Formation of New Copper Quinonoid Complexes. Z. Anorg. Chem. 2015, 641, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.A.; da Silva, C.C.; Ribeiro, L.; Karoline, A.; Valdo, S.M.; Martins, F.T. Competition between coordination bonds and hydrogen bonding interactions in solvatomorphs of copper(II), cadmium(II) and cobalt(II) complexes with 2,2′-bipyridyl and acetate. Z. Krist. Cryst. Mater. 2018, 234, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.-H.; Chen, X.-M.; Xue, F.; Ji, L.N.; Mak, T.C.W. Reaction of divalent metal acetate and 2,2′-bipyridine. Syntheses and structural characterization of mono-, bi- and tri-nuclear complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 299, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelaide, O.M.; Abidemi, O.O.; Olubunm, A.D. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial studies of some copper(II) complexes of 2,2’-bipyridine and 1,10-phenanthroline. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2013, 5, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Diao, L.-H.; Yin, X.-H. Crystal structure of bis(2,2′-bipyridine)formatocopper(II)tetrachlorate, [Cu(C10H8N2)2(CHO2)][ClO4]. Z. Krist. NCS 2010, 225, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquín, M.; Cocera, N.; Garmendia, M.J.G.; Larrínaga, L.; Pinilla, E.; Seco, J.M.; Torres, M.R. Acetato and formato copper(II) complexes with 4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine and 5,5′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine: Synthesis, crystal structure, magnetic properties and EPR results. A new 1D polymeric water chain. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, G.; Perlepes, S.P.; Libby, E.; Folting, K.; Huffman, J.C.; Webb, R.J.; Hendrickson, D.N. Preparation and Properties of the Triply Bridged, Ferromagnetically Coupled Dinuclear Copper(II) Complexes [(bipy)Cu(OAc)3Cu(bpy)](C1O4) and [(bipy)Cu(OAc)(H2O)(OH)Cu(bipy)](ClO4)2. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 3657–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonmak, J.; Youngme, S.; Chotkhun, T.; Engkagul, C.; Chaichit, N.; van Albada, G.A.; Reedijk, J. Polynuclear copper(II) carboxylates with 2,2′-bipyridine or 1,10-phenanthroline: Synthesis, characterization, X-ray structures and magnetism. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008, 11, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.K. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Characterization of Copper(II) Acetate Complex. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2001, 22, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Me´nage, S.; Vitols, S.E.; Bergerat, P.; Codjov, E.; Kahn, O.; Girerd, J.-J.; Guillot, M.; Solans, X.; Calvet, T. Structure of the linear trinuclear complex hexakis(acetato)bis(2,2′-bipyridine)trimanganese(II). Determination of the J electron-exchange parameter through magnetic susceptibility and high-field magnetization measurements. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 2666–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlepes, S.P.; Libby, E.; Streib, W.E.; Folting, K.; Christou, G. The reactions of Cu2(O2CMe)4(H2O)2 with 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy): Influence of the Cu:bpy ratio, and the structure of a linear polymer comprising two alternating types of Cu2 units. Polyhedron 1992, 11, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlepes, S.P.; Huffman, J.C.; Christou, G. Preparation and characterization of triply-bridged dinuclear copper(II) complexes containing the [Cu2(μ-OH)(μ-X)(μ-OAc)]+ core (X = Cl, Br), the crystal structure of [Cu2(OH)Cl(OAc)(bpy)2](ClO4) H2O. Polyhedron 1991, 10, 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlepes, S.P.; Huffman, J.C.; Christou, G. Preparation and characterization of dinuclear copper(II) complexes containing the [Cu2(μ-OAc)2]2+ core. Polyhedron 1992, 11, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlepes, S.P.; Huffman, J.C.; Christou, G.; Paschalidou, S. Dinuclear copper(II) complexes with the new [Cu2(μ-OR)(μ-OAc)2]+ (R = alkyl) core: Preparation and characterization of [Cu2(OR)(OAc)2(bpy)2]+ (R = Me, Et, Prn) salts. Polyhedron 1995, 14, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo-Fisher Scientific. Omnic Sortware for FT-IR Spectroscopy; Thermo-Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CrysalisPro, version 38.46; Oxford–Rigaku Corporation: The Woodlands, TX, USA.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL; Acta Crystallographica C71, 3–8. Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mercury, version 2025.1.1; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre: Cambridge, UK, 2025. Available online: https://ccdc.cam.ac.uk/mercury (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Baker, E.N.; Blundell, T.L.; Cutfield, J.F.; Dodson, E.J.; Dodson, G.G.; Hodgkin, D.M.C.; Hubbard, R.E.; Isaacs, N.W.; Reynolds, C.D.; Sakabe, K.; et al. The structure of 2Zn pig insulin crystals at 1.5 Å resolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 1998, 319, 369–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, L.J.; Orr, G.W.; Atwood, J.L. An intermolecular (H2O)10 cluster in a solid-state supramolecular complex. Nature 1998, 395, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, L.J.; Orr, G.W.; Atwood, J.L. Characterization of a well resolved supramolecular ice-like (H2O)10 cluster in the solid state. Chem. Commun. 2000, 2000, 859–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; MacDonald, J.C.; Bernstein, J. Graph-set analysis of hydrogen-bond patterns in organic crystals. Acta Crystallogr. 1990, B46, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, J.D. The structure of graphite. Proc. R. Soc. 1924, 106, 750–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narten, A.H.; Danford, M.D.; Levy, H.A. X-ray diffraction study of liquid water in the rnge 4–300 deg C. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1967, 43, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, L.B.; Huang, C.; Schlesinger, D.; Pettersson, L.G.; Nilsson, A.; Benmore, C.J. Liquid water: Benchmark oxygen-oxygen pair-distribution function of ambient water from X-ray diffraction measurements with a wide Q-range. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 074506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, R. Water: From clusters to the bulk. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1808–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narten, A.H.; Thiessen, W.E.; Blum, L. Atom pair distribution functions of liquid water at 25 °C from neutron diffraction. Science 1982, 217, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svishchev, I.M.; Kusalik, P.G. Structure in liquid water: A study of spatial distribution functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.J.; Bharadwaj, P.K. A dodecameric water cluster built around a cyclic quasiplanar hexameric core in an organic supramolecular complex of a cryptand. Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 3661–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, G.E.; Nordlander, E.; Tsipis, A.C.; Haukka, M.; Plakatouras, J.C. Synthesis, structural and theoretical studies of a rare hexameric water cluster held in the lattice of {[Zn(HL)(phen)(H2O)]∙3(H2O)}2 (H3L = trans-aconitic acid). Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2011, 14, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, X.; Yuan, D.; Weng, X. Hexagonal prismatic dodecameric water cluster: A building unit of the five-fold interpenetrating six-connected supramolecular network. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9014–9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.V.; Zaragoza, G.; Otero, M.; Pedrido, R.; Rama, G.; Bermejo, M.R. Supramolecular aggregation of Pd(II) monohelicates directed by discrete (H2O)8 clusters in a 1,4-diaxially substituted hexameric chairlike conformation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 2083–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Sarkar, B.; Ghumaan, S.; Janardanan, D.; van Slageren, J.; Fiedler, J.; Puranik, V.G.; Sunoj, R.B.; Kaim, W.; Lahiri, G.K. 2,5-Dioxido-1,4-benzoquinonediimine (H2L2−), a hydrogen-bonding noninnocent bridging ligand related to aminated topaquinone: Different oxidation state distributions in complexes [{(bpy)2Ru}2(μ-H2L)]n (n=0,1+,2+,3+,4+) and [{(acac)2Ru}2(μ-H2L)]m (m=2−,1−,0,+,2+). Chemistry 2005, 11, 4901–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Bharadwaj, P.K. Coexistence of water dimer and hexamer clusters in 3D metal−organic framework structures of Ce(III) and Pr(III) with pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 8250–8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Bharadwaj, P.K. Puckered-boat conformation hexameric water clusters stabilized in a 2D metal−organic framcwork structure built from Cu(II) and 1,2,4,5-benzenetetracarboxylic acid. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 5180–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, L.-L.; Li, C.-J.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Tong, M.-L. Coexistence of planar and chair-shaped cyclic water hexamers in a unique cyclohexanehexacarboxylate-bridged metal-organic framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custellclean, R.; Afloroaei, C.; Vlassa, M.; Polverejan, M. Formation of extended tapes of cyclic water hexmers in an organic molecule crystal host. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed.) 2000, 39, 3094–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.D. Co-operation of π⋯π, Cu(II)⋯π, carbonyl⋯π and hydrogen-bonding forces leading to the formation of water cluster mimics observed in the reassessed crystal structure of [Cu(mal)(phen)(H2O)]2·3H2O (H2mal = malonic acid, phen = 1,10-phenanthroline). J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 967, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabelo, O.; Pasán, J.; Cañadillas-Delgado, L.; Delgado, F.S.; Labrador, A.; Lloret, F.; Julve, M.; Ruiz-Pérez, C. (4,4) Rectangular lattices of cobalt(II) with 1,2,4,5-benzenetetracarboxylic acid: Influence of the packing in the crystal structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 3984–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.-S.; Wu, Y.-R.; Huang, R.-B.; Zheng, L.-S. A well-resolved uudd cyclic water tetramer in the crystal host of [Cu(adipate)(4,4-bipyridine)]·(H2O)2. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 3798–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhayra, M.; Zuhayra, M.; Kampen, M.U.; Henze, E.; Oberdorfer, F. A planar water tetramer with tetrahedrally coordinated water embedded in a hydrogen bonding network of [Tc4(CO)12-(μ3-OH)4 4H2O]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 424–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senanayake, K.; Thompson, A.L.; Howard, J.A.K.; Bottab, M.; Parker, D. Synthesis and characterisation of dimeric eight-coordinate lanthanide(III) complexes of a macrocyclic tribenzylphosphinate ligand. Dalton Trans. 2006, 45, 5423–5428. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Che, Y.; Batten, S.R.; Chen, P.; Zheng, J. Unusual T4(1) water chain stabilized in the one-dimensional chains of a copper(II) coordination polymer. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogi, S.; Savitha, G.; Bharadwaj, P.K. Structure of discrete (H2O)12 clusters present in the cavity of polymeric interlinked metallocycles of Nd(IIp) or Gd(III) and a podand ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 3771–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Bharadwaj, P.K. Structure of a discrete hexadecameric water cluster in a metal−organic framework structure. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 6887–6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchard, J.R.; Curnow, O.J.; Garrett, D.J.; Maclagan, R.G.A.R. [Cl2(H2O)6]2−: Structure of a discrete dichloride hexahydrate cube as a tris(diisopropylamino)cyclopropenium salt. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed.) 2006, 45, 7550–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada, M.; Leutwyler, S. Water hexamer clusters: Structures, energies, and predicted mid-infrared spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 2003–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapie, G.; Acelas, N.; Castano, M.; David, J.; Restrepo, R. Structural Studies of the Water Hexamer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 7809–7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|

| CCDC deposition number | 2477031 | 2477032 |

| Formula | C14H14CuN2O4·5 H2O | C14H14CuN2O4·C2H3N |

| Formula weight g/mol | 427.89 | 378.87 |

| Temperature K | 100(2) | 105(2) |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P-1 (#2) | P 2(1)/c (#14) |

| Radiation: molybdenum; Å | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a Å | 6.9252(5) | 11.7202(14) |

| b „ | 12.3844(8) | 18.8566(16) |

| c „ | 12.8498(9) | 8.1151(7) |

| α degrees | 114.869(7) | 90.000 |

| β „ | 100.207(6) | 100.894(11) |

| γ „ | 96.758(6) | 90.000 |

| Volume Å3 | 960.97(13) | 1761.1(3) |

| Z, Z’ | 2, 2 | 4, 1 |

| Density Mg/m3 | 1.479 | 1.429 |

| Absorption coefficient mm−1 | 1.184 | 1.267 |

| F(000) | 446 | 780 |

| Crystal size, mm | 1.03 × 0.21 × 0.10 | 0.40 × 0.23 × 0.12 |

| Data range, θ, degrees | 3.32 to 32.26 | 3.55 to 32.30 |

| Data collected, unique, Rint | 12,558, 6196, 0.0298 | 19,160, 5795, 0.0674 |

| Data, I > 2σI | 5597 | 3932 |

| Parameters, restraints | 265, 10 | 217, 0 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares, F2 | Full-matrix least-squares, F2 |

| Goodness of fit | 1.045 | 1.033 |

| R1, wR2 for I > 2 σI | 0.0324, 0.0858 | 0.0501, 0.1085 |

| R1, wR2 for all data | 0.0378, 0.0889 | 0.0865, 0.1309 |

| Difference ρ, max, min; e·Å−3 | +0.580, −0.830 | +1.074, −0.845 |

| Compound | Cu-O(acetate), Equatorial | Cu-O(acetate), Axial | Cu-N(bipy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.927(4), 1.952(4) | unreported | 2.015(5), 2.020(5) |

| 3 (296 K) | 1.941(3), 1.931(3) | 2.619(4), 2.745(4) | 1.989(3), 2.004(3) |

| 3 (100 K) | 1.9507(17),1.9755(18) | 2.537(2), 2.611(2) | 2.005(2), 2.010(2) |

| 4 | 1.9371(11), 1.9439(11) | 2.600(2), 2.753(2) | 1.9890(13), 2.0024(13) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Entzminger, P.D.; Valente, E.J.; Urnezius, E. The (Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate System: (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Pentahydrate (Ribbons of Planar (H2O)6 Rings Fused with Planar (H2O)4 Rings) and (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Acetonitrile Solvate. Compounds 2026, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010011

Entzminger PD, Valente EJ, Urnezius E. The (Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate System: (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Pentahydrate (Ribbons of Planar (H2O)6 Rings Fused with Planar (H2O)4 Rings) and (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Acetonitrile Solvate. Compounds. 2026; 6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleEntzminger, Paul D., Edward J. Valente, and Eugenijus Urnezius. 2026. "The (Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate System: (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Pentahydrate (Ribbons of Planar (H2O)6 Rings Fused with Planar (H2O)4 Rings) and (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Acetonitrile Solvate" Compounds 6, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010011

APA StyleEntzminger, P. D., Valente, E. J., & Urnezius, E. (2026). The (Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate System: (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Pentahydrate (Ribbons of Planar (H2O)6 Rings Fused with Planar (H2O)4 Rings) and (2,2′-Bipyridyl)copper(II) Acetate Acetonitrile Solvate. Compounds, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010011