Abstract

(1) Background: Japanese Kampo medicine has its origin in ancient Chinese medicine. In 742, a Tang Dynasty monk named Jianzhen (Ganjin) was invited by Japanese clerics to visit Japan and teach commandments in Buddhism. Because of the dangers of the voyage and also other obstacles, he took 11 years to reach Japan on the sixth voyage and he was blind when he arrived in Japan. He was the first person in China to go to Japan to establish the Buddhism commandments, and he was also the first person in Japan to directly teach traditional Chinese medicine. Until now, there have been few reports in English about the details of the Chinese herbal medicines he brought to Japan, including the types of herbal medicines, pharmacological activities, and formulations. In the review, we systematically and comprehensively summarized Jianzhen’s life from the standpoint of his medical and pharmaceutical knowledge and the types and pharmacological activities of Chinese herbal medicines and prescriptions that were brought to Japan by Jianzhen; (2) Methods: A review was made on the relevant literature written by Chinese, Japanese, and English languages regarding the medical and pharmacological knowledge of Jianzhen, the 36 Chinese herbal medicines brought to Japan by Jianzhen, and the pharmacological and therapeutic effects of these 36 herbal medicines, as well as their formulations; (3) Results: The review of the literature proved that Jianzhen’s prescriptions served as a basis for current herbal medicines (Kampo) in Japan. In the process of the literature search, we found a book entitled Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription, which recorded the complete prescription of the 36 traditional Chinese medicines Jianzhen brought to Japan; (4) Conclusions: Jianzhen is one of the ancestors of traditional Chinese medicine/Kampo medicine, and he brought traditional Chinese medicine and medical books to Japan for patients. He made important contributions to the development of traditional Chinese medicine in Japan.

1. Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine has a history of approximately 3000 years from the early Zhou Dynasty in China and even earlier, and the oldest medical writings on herbal medicine are found in the Book of Songs and the Book of Changes []. The sources of traditional Chinese medicine include plants, animals, and minerals. Herbal medicines make up the largest proportion and are most commonly used. As the accumulated knowledge was recorded in medical books, traditional Chinese medicine evolved into an independent discipline. Traditional Chinese medicine focuses on the balance of yin and yang to maintain health and prevent diseases. Once the balance is disrupted, it leads to different diseases or syndromes []. The purpose of traditional Chinese medicine is to correct the disrupted balance and restore the body’s ability to self-regulate but not to fight against specific pathogenic targets. According to the traditional Chinese medicine theory, disruption in diseases can be divided into several “patterns”. A disease may show several different “patterns” and be treated with several herbal medicines. Different diseases may be treated with the same herbal medicine due to their shared patterns. [].

This article reviews how Jianzhen (Figure 1) acquired medical and pharmaceutical knowledge in his younger age from the viewpoint of traditional Chinese medicine brought to Japan, and summarizes the methods of identifying Chinese herbal medicines and part of prescriptions of herbal medicines. To this end, we introduced, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, a book that recorded the complete prescription of traditional Chinese medicine that Jianzhen brought to Japan named Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription.

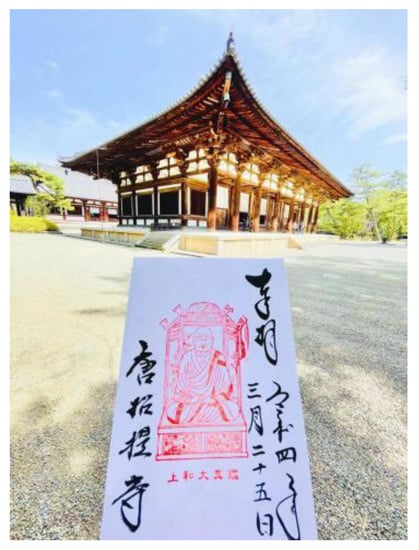

Figure 1.

Jianzhen’s image stamped on the certificate with the date (25 March, 4th year of Reiwa, 2022) for visit at Toshodaiji Temple, Nara, Japan. Authors’ original photograph taken in the background of Main Hall (Kondo).

2. Methods

PubMed, CNKI, J-STAGE, and Google Scholar were searched in Chinese, Japanese, and English with the terms “Jianzhen/Ganjin, Chinese medicine, Kampo”. Additional information regarding the historical literature and herbal books was found in Okayama University Library. Ethnopharmacological reviews were based on interdisciplinary comparisons among botany, pharmacology, traditional Chinese medicine, and history. We focused on the history of Chinese herbal medicines that Jianzhen brought to Japan and discussed the historical development and current situation of these Chinese herbal medicines in Japan. The plant names were checked with http://mpns.kew.org, accessed on 21 June 2022.

3. Jianzhen’s Background in Medicine and Pharmacy

Jianzhen became a monk in Dayun Temple, Yangzhou, when he was 14 years old. At the age of 20, he followed his teacher Daoan (654–717) to study in two capitals (Luoyang and Chang’an) of the Tang Dynasty. Daoan’s teacher was Wengang (636–727), Wengang’s teacher was Hongjing (634–712), and Hongjing was a disciple of Daoxuan (596–667). Daoxuan was the founder of Nanshan Buddhism. Daoxuan made Tianwang Buxin Pills by himself as he suffered from heart disease. Daoxuan had a deep friendship with Sun Simiao (581–682), and Sun Simiao was a well-known doctor and pharmacy expert in China in the Tang Dynasty. Sun Simiao was known as the King of Medicine in China and is the author of A Thousand Gold Prescriptions and other books. Daoxuan learned a lot of medical knowledge from Sun Simiao and passed it on to Hongjing, who then passed it on to Jianzhen. They influenced and learned from each other in medicine and knowledge of Buddhism [].

Jianzhen was born in Yangzhou, which was a traffic crossing point between the north-to-south canal and the Yangtze River. At that time, it was a city for international communication, a traffic tunnel for land, and water transportation. Jianzhen could see goods and medicines from all over the world in Yangzhou. Because of this unique geographical environment, Jianzhen mastered a lot of the knowledge for identifying the varieties, specifications, processing, and distinguishing the true from the false medicine [].

Later, he went to Beijing and visited the imperial hospital and the pharmacy garden, where the imperial medicine garden and the medicine storehouse were located. The world’s first pharmacopoeia Newly Revised Materia Medica was promulgated here. Newly Revised Materia Medica is a book on clinical medicinal materials wrote by Su Jing (599–674) in the Tang Dynasty []. Jianzhen learned a lot of medical and pharmaceutical knowledge here.

In addition to being proficient in Buddhism and medicine, Jianzhen was also very proficient in other things, such as calligraphy, architecture, sculpture, art and crafts, and the Five Sciences. The Five Sciences in Buddhism refer to five academic fields: 1. Shengming/Shomyo (phonology and grammar); 2. Gongqiaoming/Kugyomyo (technics and technology); 3. Yifangming/Ihomyo (medical science); 4. Inming/Inmyo (ethics); 5. Neiming/Naimyo (study of a scholar’s religion, as in Buddhism for a Buddhist). He participated in the work of Longxing Temple and Daming Temple (Figure 2A,C), carried out voluntary medical treatment, and gained a great deal of clinical experience and medical knowledge in practice [].

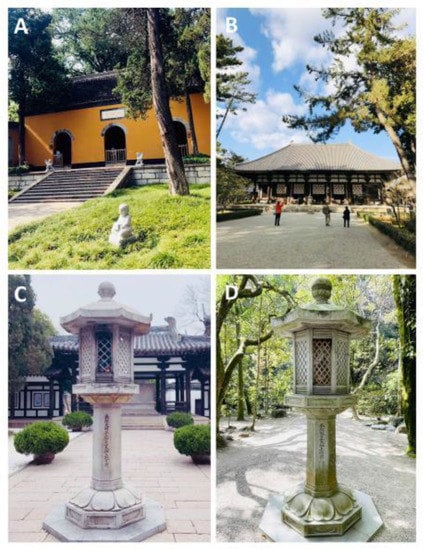

Figure 2.

Photos of Daming Temple in Yangzhou, China, and Toshodaiji Temple in Nara, Japan. (A): Daming Temple, (B): Kondo (main hall) built in the late 8th century in Toshodaiji Temple, (C): Twin stone lanterns at Daming Temple given as a gift, (D): Original stone lantern of Toshodaiji Temple. (Authors’ original photographs).

4. Six Voyages to Japan

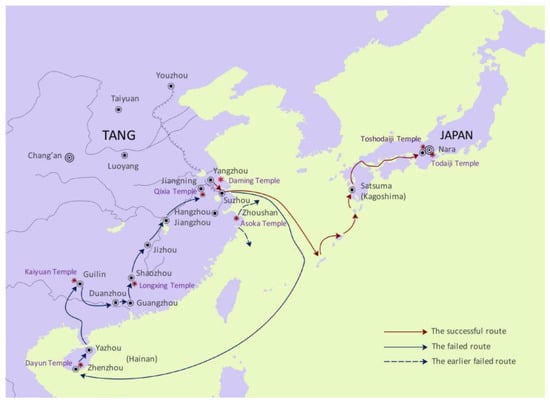

In 742 AD, two Japanese clerics from Japan, named Rong Rui/Yoei and Pu Zhao/Fusho, went to Daming Temple in Yangzhou to invite Jianzhen to Japan. They had the responsibility to invite Chinese monks to teach precepts in Japan, and they had visited many places in China, but they had never seen a monk such as Jianzhen, who was proficient in a lot of knowledge. Therefore, they decided to invite Jianzhen to travel to Japan to teach the precepts and also hoped that he could bring other academic help. Jianzhen promised them and went to Japan by ship starting in 743, but he failed five times. In 753, after obstacles and difficulties, finally, he arrived in Japan after six voyages, and he was blind [] (Figure 3, modified from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jianzhen, accessed on 1 June 2022, Table 1).

Figure 3.

The map of Jianzhen’s eastward voyages to Japan.

Table 1.

Jianzhen’s six voyages to Japan.

5. Traditional Chinese Medicines Brought to Japan

Jianzhen took a large number of herbal medicines, spices, and medical books to Japan. He brought 36 kinds of herbal medicines from China to Japan, each herbal medicine with different pharmacological effects, and recipes for their different combinations to treat a variety of diseases (Figure 4, Table 2). The spices and the other things that he brought to Japan included musk, agarwood, snail, rosin, dipterocarp, fragrant gall, benzoin, incense, dutchman’s pipe root, pistacia lentiscus, piper longum, terminalia chebula/haritaki, asafoetida, sugar, sucrose, 10 bushels of honey, 80 bunches of sugar cane, and so on. In addition, Jianzhen also collected the medicines and objects that he encountered on the way to Japan and took them to Japan: for example, Stalactites and Zixue. During his stay in Guilin in the southern part of China, he saw many cauliflower stones (stalactites) that could be used as medicine, so he also brought them to Japan []. On their fifth trip to Japan, they drifted to Hainan, a southern island. During his stay in Hainan, due to the high temperature, beriberi was prevalent in this area. He found a new prescription and brought it to Japan []. After coming to Japan, Jianzhen built a medicinal garden in Toshodaiji Temple (Figure 2B,D) to grow medicinal herbs. Then, he distributed the herbal medicines to patients who helped themselves treat their illnesses [].

Figure 4.

Some representative herbal medicines in Table 2 exhibited currently at a drug shop in Japan. (A): Paeonia lactiflora Pall, (B): Glycyrrhiza glabra L., (C): Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, (D): Conioselinum anthriscoides ‘Chuanxiong’, (E): Inula japonica Thunb., (F): Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC., (G): Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino, (H): Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis, (I): Phellodendron chinense C.K.Schneid., (J): Prunus amygdalus Batsch, (K): Cortex of Magnolia officinalis Rehder and E.H.Wilson, (L): Cinnamomum verum J.Presl, (M): Eucommia ulmoides Oliv., (N): Ziziphus jujuba Mill., (O): Rheum palmatum L. (Authors’ original photographs).

Table 2.

36 kinds of herbal medicines brought into Japan by Jianzhen.

Before the arrival of Jianzhen, in the Asuka and Nara periods (6th to 8th centuries), traditional Chinese medicine was adopted in Japan, and the first medical law (Ishitsuryo in the Taiho Code, 701 AD) was enacted during the reform period in the early 8th century []. The Ishinho (Ishinpo) is the oldest medical book, consisting of 30 volumes, expounding the importance of foreign medical literature (such as traditional Chinese medicine) to the development of Japanese medicine. All these 36 kinds of herbal medicines are well developed in Japan and are called Kampo medicine now []. Japan formulated traditional Chinese medicine into Kampo medicine suitable for the constitution of the Japanese people’s bodies (Yoshiko Takahashi, 2019, https://www.premium-j.jp/en/japanesesenses/20190814_2783/#page-1, accessed on 1 June 2022). The representative prescriptions are in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative prescriptions sold currently in Japan that would have origins in Jianzhen’s herbal medicines.

6. Methods of Identifying Herbal Medicines

Jianzhen formed his own specialty in medicinal identification in years of accumulation and the study of medical knowledge. After six eastward crossings, he was blind in both eyes, but he was still able to identify medicines by smelling with his nose, tasting with his tongue, and touching with his fingers. He corrected many wrong methods of drug identification in Japan, and taught the Japanese how to collect and concoct drugs, which added a lot of pharmaceutical knowledge to Japan [,]. In the past, a portrait of Jianzhen was printed on the wrapping paper of many Kampo medicines in Japan to commemorate him.

7. Various Prescriptions Brought to Japan

In terms of medical works, Jianzhen had an original book called Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription. In the ancient literature in the 9th to the early 10th century in Japan, such as in Fujiwara Sukeyo’s book and Fukane Sukehito’s book, Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription was mentioned. The Ishinho (Ishinpo), written by Tanba Yasuyori in 984, is the oldest extant medical work in Japan that was passed down to the present day []. There are three or four prescriptions by Jianzhen that can be found in these books. However, Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription has been lost for a long time. According to the reference [], 14 prescriptions were found in ancient Japanese medical references (Table 4). Jianzhen was said also to prescribe medicine to Emperor Shomu and Empress Komyo at that time for treating them [].

Table 4.

Combination prescriptions and other symptom-based prescriptions brought to Japan by Jianzhen.

8. Look for the Lost Original Prescriptions

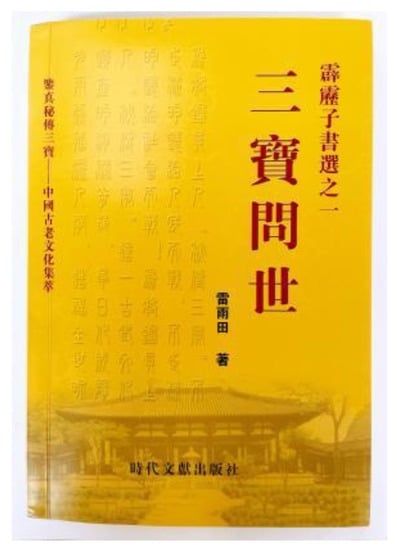

Jianzhen brought a lot of precious prescriptions from China to Japan, but the prescriptions were lost []. We searched in various ways and found the original version of Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription on the internet to identify the author’s name and the book that recorded the Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription. However, unfortunately, the book was out of print and was not available in bookstores and online, even as a second-hand book. Fortunately, we finally found the book through various ways. The author of this book is Lei Yutian, who is the 52nd generation from the passage of Jianzhen’s secret three treasures, including Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription.

In 2009, he decided to disclose Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription, which was published in the book entitled Three Treasures Be Published (Figure 5). Before Jianzhen went to Japan, he passed the same prescriptions to his disciple, the monk Lingyou, and took the other one to Japan by himself. In Lei Yutian’s book, he told us that the prescriptions preserved in this book and the prescriptions that Jianzhen brought to Japan are similar to sisters. Lei Yutian belongs to the 52nd generation of the passage, and all prescriptions were kept under wraps until he passed it on to the next generation. In his generation, he decided to organize all prescriptions into a book and make it public to the world for the benefit of people in the world and to promote China–Japan peace and friendship.

Figure 5.

The book entitled “Three Treasures Be Published” which includes Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription. (Authors’ original photograph).

This book collected all the prescriptions that Jianzhen brought to Japan. There is a total of 120 groups (1200 prescriptions) in 24 chapters, including prescriptions for soup, pill, powder, ointment, dan, liquor/Chinese rice wine, smoke, wash, and compress. After 52 generations of inheritance, some prescriptions have been lost, leaving only 766 prescriptions [].

From this book, we know that when choosing herbal medicines, it is necessary to choose high-quality medicinal materials that feel and taste good, not to use alternative medicinal materials, and to choose the right origin and seasonal herbal medicines. Each medicine should be carefully identified by eyes, nose, tongue licking, hand touch, and other methods to ensure that good medicinal materials are used. For pharmaceutical preparation, after the selection of herbal medicines, the medicine is prescribed and dosed according to the prescription. It is recommended to soak the herbal medicine in water for 1 to 2 h and then to boil it for half an hour, and to take the medicine twice a day in the morning and evening by drinking half a bowl each time [].

9. The Revival of Toshodaiji Medicine Garden

World Heritage Toshodaiji Temple in Nara, Japan, is the place that was built for Jianzhen to live in. According to a press release from Toshodaiji Temple, the herb garden of Toshodaiji Temple is currently rebuilt, named “Fragrant herb garden” (Figure 6) [], and is expected to be completed in 2024. In 1999, for the restoration work of Kondo, the herb garden was temporarily demolished, the herbs and medicinal trees were transferred to the “Sacred Medicine Garden” built in the area of Seki City, Gifu Prefecture. About 150 types of herbs and trees were transplanted, and volunteers in Gifu took care of these plants. This time, they decided to return the herbs and medicinal trees to Toshodaiji Temple and rebuild the herb garden of about 2240 square meters.

Figure 6.

Herb garden under construction at Toshodaiji Temple. (Authors’ original photograph).

10. Discussion

First, we compared the types of traditional Chinese medicine/Kampo medicine that exist in China and Japan in the Tang Dynasty and Nara period, respectively, and also nowadays. In China, in approximately the 11th century BC–6th century BC, the Book of Songs recorded more than 130 species of plants, including Zanthoxylum bungeanum maxim, Artemisia carvifolia. In the Qin and Han Dynasties, Shennong Classic of Materia Medica is the earliest extant work on traditional Chinese medicine, with a total of 365 kinds of traditional Chinese medicine. In the Tang Dynasty, Newly Revised Materia Medica recorded approximately 850 kinds of traditional Chinese medicine. Nowadays, the book Chinese Materia Medica has a total of 24 million words, a total of 35 volumes, and records a total of 8980 kinds of traditional Chinese medicine. On the other hand, in Japan’ Nara period, there are 60 kinds of Kampo medicines that were preserved in the Shoso-in of Todaiji Temple []. Nowadays, there are more than 300 kinds of crude drugs, and more than 294 kinds of Kampo medicines in Japan [].

Second, before the book Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription was found, everyone thought it had disappeared in the world. Fortunately, we found it before it disappeared completely. It has not yet been included in the intangible cultural heritage. As we all know, intangible cultural heritage itself is very fragile. Everything has a process of generation, growth, continuation, and extinction, and the remains of intangible cultural heritage are also in such a dynamic process. We hope to draw more people’s attention to protect many intangible cultures that are about to disappear, including Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription.

In the history of pharmacopoeia, the facts that Jianzhen was invited to Japan to teach Buddhism, medicine, and medicine identification are described in Japan’s textbook of pharmacognosy (Revised Ninth Edition) []. However, there is no record of the original source of the crude drugs and the Chinese herbal medicine that Jianzhen brought to Japan. We hope this review would fill this gap in the historical knowledge.

Third, another basic theory of traditional Chinese medicine is the five elements theory, which describes the human body and herbs with five elements (water, wood, metal, fire, and earth). For example, “water” represents the kidneys, bladder, and ears; “wood” represents the liver and gallbladder; “metal” represents the lungs and large intestine; “fire” represents the heart, small intestine, and tongue; and “earth” represents the spleen and stomach. All organs of the body are also connected and can be influenced according to the properties of certain herbs [,]. The relationship of mutual generation, restraint, pressure, and inversion among the five elements is mapped to the physiological and pathological relationship of the five organs (liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney) []. Traditional Chinese medicine is based on color and taste and is classified according to the theory of the five elements: bitter/red (heart), sweet/yellow (spleen), sour/green (liver), spicy/white (lung), and salty/black (kidney) [].

Chinese herbal medicines can be extracted from roots, stems, leaves, bark, flowers, fruits, seeds, and whole plants []. We found that the traditional Chinese medicine that Jianzhen brought to Japan included many rhizomes of plants (Table 2). In the theory of traditional Chinese medicine, the roots and rhizomes were believed in ancient China to help restore the inner energy of the human body [,]. This would be one of the reasons that a large proportion of Chinese medicinal materials is classified into those categories.

In general, compounds are divided into organic compounds and inorganic compounds by composition. From the standpoint of chemical bonds, compounds are divided into ionic compounds, covalent compounds, and coordination compounds. There are nearly 16 million known organic compounds, while only hundreds of thousands of inorganic compounds were discovered []. Many natural synthetic drugs are closely related to organic compounds, and drugs that were developed from plants, actinomycetes, and fungi are organic compounds. Currently, many research institutions provide compound libraries for researchers to conduct research and to develop new small molecule drugs []. Chinese herbal medicines would serve as new resources in compound libraries in order to discover more useful organic compounds. Chinese herbal medicine is one of the important sources that contains many unexplored compounds. Through various chemical techniques, new organic compound libraries can be established by gathering natural medicines as precursors.

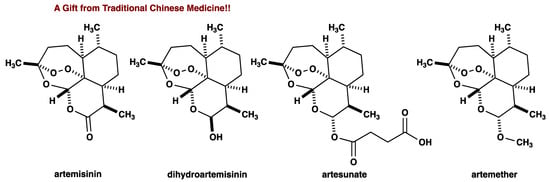

The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine was awarded to Satoshi Omura of Japan, Youyou Tu of China, and William Cecil Campbell of Irish-born American descent. Omura collected soil samples from various places, isolated and cultivated microorganisms, and studied whether the chemicals produced by the microorganisms were useful. Later, a new species of bacteria was discovered in soil collected from Shizuoka Prefecture, and the antibiotic “Avermectin”, which can drastically reduce parasites, was discovered. Omura’s research team developed “Ivermectin”, which has become a special medicine for diseases such as “river blindness” and “elephantiasis” in Africa and other places []. Another Nobel laureate, Youyou Tu, discovered the anti-malarial drug, artemisinin, in the repertory of traditional Chinese medicine (Figure 7). This herb (artemisinin) was known to treat fever as early as 1700 years ago, and what Youyou Tu did was to explain which component of the herb was biologically active. She studied the chemistry of traditional Chinese medicine for many years to combine pharmacology, preparation, and clinical practice. Based on the research of traditional Chinese medicine, she used modern science and technology to explore the active ingredients of traditional Chinese medicine. Her most prominent contribution is the development of new anti-malarial drugs, artemisinin and dihydroartemisinin []. Youyou Tu’s research team also found that dihydroartemisinin has a unique effect on the treatment of lupus erythematosus with high variability, and clinical trials were carried out [,]. Satoshi Omura found medicines in soil microorganisms, and Youyou Tu extracted medicines from traditional Chinese medicine. Therefore, traditional Chinese medicine may serve as a huge drug resource library to develop more new drugs to treat patients. From the herbal medicines brought to Japan by Jianzhen, we will continue to discover and extract useful active molecules to treat more diseases in patients and to make greater contribution to human health.

Figure 7.

Structures of artemisinin and its clinically used derivatives.

In the recent epidemic of 2019-nCoV pneumonia (COVID-19), traditional Chinese medicine has also played a great role in curing the disease. In China, according to the overall symptoms of patients with COVID-19, traditional Chinese medicine recommends prescriptions that may be effective, such as Qingfei Paidu Decoction (QPD), etc. Ephedrae Herba, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma Praeprata cum Melle, Cinnamomi Ramulus, Alismatis Rhizoma, Armeniacae Semen Amarum, Gypsum Fibrosum, Polyporus, Bupleuri Radix, Belamcandae Rhizoma, Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Scutellariae Radix, Pinelliae Rhizoma Praepratum cum Zingibere et Alumine, Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma, Poria, Zingiberis Rhizoma Recens, Asteris Radix et Rhizoma, Farfarae Flos, Dioscoreae Rhizoma, and Pogostemonis Herba Aurantii Fructus Immaturus, and Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium were promoted as general prescriptions in the diagnosis of COVID-19 []. Network pharmacology analysis has shown that QPD has a multi-component, multi-target overall regulatory effect []. Indeed, the case report in that article [] described that a patient who received QPD treatment had significant improvement in clinical symptoms and imaging examinations. The three highly recommended Chinese patent medicines (CPMs) in the treatment of COVID-19 are Lianhua Qingwen Capsules (granules), Jinhua Qinggan Granules, and Hexuebijing Injection. In the other review article, evidence-based scientific findings were integrated to show that three Chinese herbal formulas (QPD, Fahrenheit Baidu Fang, and Xuanfei Baidu Fang) were proven to be effective in treating COVID-19 through the methods of retrospective cohort study, randomized controlled trial, multi-center clinical observation, and case analysis []. Traditional Chinese medicine plays an important role in the treatment of various diseases, including COVID-19, in China. On the other hand, in Japan, many COVID-19 patients received a combination of Kampo medicine together with or without modern medicine. The therapeutic effect is being studied as a research project at the Japan Society for Oriental Medicine (JSOM). Under the circumstances, QPD is not used in Japan because it includes crude drugs in traditional Chinese medicine that were not approved by Japanese regulators []. We should conduct a more in-depth analysis of the molecular activity and molecular mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine and develop effective drugs to treat patients’ diseases.

In the field of Ophthalmology, traditional Chinese medicine was also used to treat patients with eye diseases in the modern era. Professor Xingwei Wu is the first person to obtain a doctorate in ophthalmology of integrated traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine in China. He advocates three prescriptions of traditional Chinese medicine to treat eye diseases: Canqi (Shenqi) Wangmo granules for fundus hemorrhage, Diling Wangmo granules for central serous chorioretinopathy, Lingqi Huangban for age-related macular degeneration, etc. []. He said that the efficacy of multi-target therapy in the combination of Chinese and Western medicine is better, compared with a single treatment of either Western medicine or Chinese medicine [].

In collecting the herbal medicines (Table 2) that Jianzhen brought to Japan, we can find various pharmacological effects of herbal medicines. When herbal medicines would be innovated with scientific concepts and technologies, more drug effects would be discovered. Some herbal ingredients were identified while still many herbal ingredients remain unknown. Over the past few decades, an empirical and scientific basis has been established to justify the future use of traditional Chinese medicine []. We could obtain a new insight in traditional Chinese medicine by applying the current new technologies to Chinese herbal medicine, such as analytical chemistry [,], network pharmacology [], systems biology [], computational modeling [], and nanotechnology [].

11. Conclusions

In this review, we shared information on what Jianzhen brought to Japan as prescriptions of traditional Chinese medicine and introduced a book entitled Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)’s Secret Prescription. Jianzhen brought 36 kinds of Chinese herbal medicine and medical books to Japan, and he cured many patients’ diseases. Jianzhen’s prescriptions serve as a basis for current herbal medicines (Kampo) in Japan. Currently in Japan, herbal medicines (Kampo) are prescribed, together with other modern drugs, at the same clinical setting, and are covered by the reimbursement of the national health insurance. We hope that more pharmacological effects of traditional Chinese medicine would be elucidated to bring more new treatments to patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L., T.M. and T.A.; investigation, S.L.; resources, S.L.; visualization, S.L.; structures, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, C.M., T.M., T.A. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Okayama AEON drug store for allowing us to take photos of the herbal medicines (Figure 4). We also thank Lei Yutian for disclosing all of Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reid, D. The Shambhala Guide to Traditional Chinese Medicine; Shambhala Publications: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. Progress in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Trends Pharm. Sci. 1995, 16, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.-Y. Therapeutic wisdom in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A perspective from modern science. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2005, 26, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, T.-J. The beginning and end of Jianzhen’s visit to Japan to teach Chinese medicine. Jiangsu Zhongyi 1963, 3, 19–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Yan, H.; Chen, L.; Ren, Y. Historical Evolution of Traditional Medicine in Japan. Chin. Med. Cult. 2019, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Yu, F. An Exploration of the Motives of Jianzhen Buddhism’s Eastern Transmission. Overseas Chin. Gard. China 2020, 7, 91–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W. To explore the relationship between Buddhism and medicine in Tang Dynasty from the medical activities of Jianzhen. Knowl. Anc. Med. Lit. 1998, 2, 28–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Geng, T.-J.; Geng, Y.-X. Talking about the statue of Jianzhen returning to China to visit relatives. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1980, 21, 67–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.-H. An Opinion on Jianzhen’s Contribution to Japanese Medicine. Jpn. Stud. 1988, 3, 25–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Gao, N.; Wang, Y.; Chang, P.; Tong, Y.; Fu, S. Clinical Studies on the Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia With Traditional Chinese Medicine-A Literature Analysis. Front Pharm. 2020, 11, 560448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C. The genus Asarum: A review on phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology and pharmacokinetics. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 282, 114642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of paeoniflorin and total glucosides of paeony. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 207, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyirimigabo, E.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Agyemang, K.; Zhang, Y. A review on phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology studies of Aconitum. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Polygalae Radix: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics. Fitoterapia 2020, 147, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; Chen, W.; Vong, C.-T.; Yao, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; et al. Astragali Radix (Huangqi): A promising edible immunomodulatory herbal medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 258, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Song, Q.; Li, R.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. An “essential herbal medicine”-licorice: A review of phytochemicals and its effects in combination preparations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 249, 112439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fang, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, X. Sophora flavescens Ait.: Traditional usage, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important Traditional Chinese Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 172, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.-L.; Zeng, R.; Gu, C.-M.; Qu, Y.; Huang, L.-F. Angelica sinensis in China-A review of botanical profile, ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and chemical analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 190, 116–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, L.; Hou, A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Man, W.; Zheng, S.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; et al. Botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, analytical methods, processing, pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of Bupleuri Radix: A systematic review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Gao, F.; Fu, Q.; Fu, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, J. A systematic review on the rhizome of Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. (Chuanxiong). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, A.; Wang, Y. Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl: A review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control and pharmacokinetics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-X.; Li, M.-X.; Jia, Z.-P. Rehmannia glutinosa: Review of botany, chemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Qiu, J.-F.; Ma, L.-J.; Hu, Y.-J.; Li, P.; Wan, J.-B. Phytochemical and phytopharmacological review of Perilla frutescens L. (Labiatae), a traditional edible-medicinal herb in China. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Gao, W.; Huang, L. Tanshinones, Critical Pharmacological Components in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Tang, H.; Xie, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Sun, Q.; Li, X. Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. (Lamiaceae): A review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, N.; Li, M.; Liu, Y. Platycodon grandifloras—An ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 164, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Hou, A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Man, W.; Yu, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; et al. A review of the botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of the Flos Inulae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonrungsesomboon, N.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Karbwang, J. Therapeutic potential and pharmacological activities of Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, W.-R.; Shi, W.-T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.-Y.; Ding, Q.; Chen, X.-L.; Tang, J.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-Y. Pharmacological Activity, Pharmacokinetics, and Toxicity of Timosaponin AIII, a Natural Product Isolated from Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge: A Review. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; He, Z. Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit: A review of its germplasm resources, genetic diversity and active components. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.-C.; Zheng, G.; Jia, L.-Y.; He, X.; Zhang, C.-F.; Wang, C.-Z.; Yuan, C.-S. Comprehensive evaluation on anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic activities in vitro of fourteen flavonoids from Daphne Genkwa based on the combination of efficacy coefficient method and principal component analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 268, 113683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.; Tao, W.; Wang, P.; Tian, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Gardenia jasminoides Ellis: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological and industrial applications of an important Traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 257, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, L.; Yang, H. Schisandra chinensis Fructus and Its Active Ingredients as Promising Resources for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Lenon, G.-B.; Yang, A.-W.-H. Phellodendri Cortex: A Phytochemical, Pharmacological, and Pharmacokinetic Review. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 7621929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-Y.; Wu, L.-J.; Wang, W.-X.; Xie, P.-J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, F. Amygdalin—A pharmacological and toxicological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 254, 112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Wu, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Fan, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, Z. A review of the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Magnoliae officinalis cortex. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 236, 412–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, S.; Yonezawa, T.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Cha, B.-Y.; Teruya, T.; Takami, M.; Yagasaki, K.; Nagai, K.; Woo, J.-T. Honokiol inhibits osteoclast differentiation and function in vitro. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Fan, S.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L. Cinnamomum cassia Presl: A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicology. Molecules 2019, 24, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Tang, L.; He, J.-W.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.-Z. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Properties of Eucommia ulmoides: A Review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2019, 47, 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; He, J.; Nisar, M.-F.; Li, H.; Wan, C. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Chaenomeles speciosa: An Edible Medicinal Chinese Mugua. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 9591845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Bao, T.; Mo, J.; Ni, J.; Chen, W. Research advances in bioactive components and health benefits of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) fruit. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2021, 22, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Rong, H.; Tu, H.; Zheng, B.; Mu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, X.; Peng, W.; Wu, M.; Zhang, E.; et al. Molecular basis of neurophysiological and antioxidant roles of Szechuan pepper. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, J.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. (Rutaceae): A Systematic Review of Its Traditional Uses, Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, and Toxicology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, C. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicology of the fruit of Tetradium ruticarpum: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, H.; Zuo, J.; Guo, F.; Dong, D. What we already know about rhubarb: A comprehensive review. Chin Med. 2020, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, T. Acupuncture and Moxibustion Medical System in Japan. Proceedings of 1st JSAM International Symposium of Evidence-based Acupuncture, Kyoto, Japan, 20–21 November 2006; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y. Kampo, Which Developed Its Own Style, Is Now Drawing Attention around the World. Available online: https://www.premium-j.jp/en/japanesesenses/20190814_2783/#page-1 (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Yoshino, T.; Arita, R.; Horiba, Y.; Watanabe, K. The use of maoto (Ma-Huang-Tang), a traditional Japanese Kampo medicine, to alleviate flu symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komuro, A. Chapter 14—Kampo Medicines for Infectious Diseases. In Japanese Kampo Medicines for the Treatment of Common Diseases, Focus on Inflammation; Arumugam, S., Watanabe, K., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, K.; Fukui, K.; Nakamura, E.; Oka, M.; Ota, K.; Sakaue, M.; Sano, Y.; Takasu, A. Effect of Shakuyaku-kanzo-to in patients with muscle cramps: A systematic literature review. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2020, 21, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, T.; Kondoh, T.; Nagura, S.; Toriumi, Y.; Kumano, H.; Tomioka, H. Improvement of C-reactive protein levels and body temperature of an elderly patient infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa on treatment with Mao-bushi-saishin-to. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2000, 6, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuboyama, T.; Hirotsu, K.; Arai, T.; Yamasaki, H.; Tohda, C. Polygalae Radix Extract Prevents Axonal Degeneration and Memory Deficits in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Pharm. 2017, 8, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, F.; Kobayashi, M.; Komatsu, Y.; Kato, A.; Pollard, R.-B. Keishi-ka-kei-to, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine, inhibits pulmonary metastasis of B16 melanoma. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 873–878. [Google Scholar]

- Katsura, T. The Remarkable Effect of Kanzo-to and Shakuyakukanzo-to, in the Treatment of Acute Abdominal Pain. Kampo Med. 1995, 46, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, H.; Asada, Y.; Horio, T. Inhibitory effect of shofu-san, a Japanese kampo medicine, on neutrophil functions in vitro. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1998, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedhar, R.; Arumugam, S.; Thandavarayan, R.-A.; Giridharan, V.-V.; Karuppagounder, V.; Pitchaimani, V.; Afrin, R.; Harima, M.; Nakamura, T.; Ueno, K.; et al. Toki-shakuyaku-san, a Japanese kampo medicine, reduces colon inflammation in a mouse model of acute colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, I. Sho-saiko-to: Japanese herbal medicine for protection against hepatic fibrosis and carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, D84–D90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, E.; Satoh, T.; Toriizuka, K.; Nagai, H.; Nunome, S.; Shimada, Y.; Itoh, T.; Terasawa, K.; Saiki, I. Effect of Shimotsu-to (a Kampo medicine, Si-Wu-Tang) and its constituents on triphasic skin reaction in passively sensitized mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 68, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawasai, O.; Yamadera, F.; Iwasaki, K.; Arai, H.; Taniguchi, R.; Tan-No, K.; Sasaki, H.; Tadano, T. Effect of kami-untan-to on the impairment of learning and memory induced by thiamine-deficient feeding in mice. Neuroscience 2004, 125, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Sakamoto, S.; Matsuda, M.; Kyokuwa, M.; Namiki, H.; Kuwa, K.; Kawashima, S.; Nagasawa, H. Suppression of spontaneous development of uterine adenomyosis and mammary hyperplastic alveolar nodules by Chinese herbal medicines in mice. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1993, 21, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Hirose, E.; Ishida, T.; Hori, A.; Nagai, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kiyohara, H.; Oikawa, T.; Hanawa, T.; Odaguchi, H. Kososan, a Kampo medicine, prevents a social avoidance behavior and attenuates neuroinflammation in socially defeated mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.-X.; Wang, P.-Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z. Different network pharmacology mechanisms of Danshen-based Fangjis in the treatment of stable angina. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, Y. Studies on antiinflamatory effect of Japanese Oriental medicines (kampo medicines) used to treat inflammatory diseases. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 18, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saeki, T.; Nikaido, T. Evaluations of saponin properties of HPLC analysis of Platycodon grandiflorum A. DC. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2003, 123, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Takano, S.; Kobayashi, T. Keishikajutsubuto (Guizhi-shu-fu-tang) treatment for refractory accumulation of synovial fluid in a patient with pustulotic arthro-osteitis. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2007, 53, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Umeda, S.; Kawashima, K.; Kano, Y. Pharmacological properties of traditional medicines. XXVI. Effects of Sansohnin-to on pentobarbital sleep in stressed mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 23, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Urushiyama, H.; Jo, T.; Yasunaga, H.; Michihata, N.; Yamana, H.; Matsui, H.; Hasegawa, W.; Hiraishi, Y.; Mitani, A.; Fushimi, K.; et al. Effect of Hangeshashin-To (Japanese Herbal Medicine Tj-14) on Tolerability of Irinotecan: Propensity Score and Instrumental Variable Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, H.; Koine, T.; Baba, M.; Okuyama, T. Pharmacological effects of Daphne genkwa and Chinese medical prescription, “Jyu-So-To”. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2004, 124, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Miura, N.; Ohtake, N.; Amagaya, S.; Ishige, A.; Sasaki, H.; Komatsu, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Ito, T.; Terasawa, K. Genipin, a metabolite derived from the herbal medicine Inchin-ko-to, and suppression of Fas-induced lethal liver apoptosis in mice. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogiso, H.; Ikeuchi, Y.; Sumiya, M.; Hosogi, S.; Tanaka, S.; Shimamoto, C.; Inui, T.; Marunaka, Y.; Nakahari, T. Seihai-to (TJ-90)-Induced Activation of Airway Ciliary Beatings of Mice: Ca2+ Modulation of cAMP-Stimulated Ciliary Beatings via PDE1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Morisaki, T.; Koyama, S.; Donishi, R.; Takeuchi, H. Unseiin, a Kampo medicine, Reduces the Severity and Manifestations of Skin Toxicities Induced by Cetuximab: A Case Report. Yonago Acta. Med. 2020, 63, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagoshi, M.; Amagaya, S.; Ogihara, Y. Antitussive effects of L-ephedrine, amygdalin, and makyokansekito (Chinese traditional medicine) using a cough model induced by sulfur dioxide gas in mice. Planta Med. 1986, 4, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagohashi, K.; Tamura, T.; Ohara, G.; Satoh, H. Effect of a traditional herbal medicine, hangekobokuto, on the sensation of a lump in the throat in patients with respiratory diseases. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 4, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoo, Y.; Su, S.-B.; Xie, M.-J.; Mouri, H.; Taga, H.; Sawabu, N. Effect of herbal medicine keishi-to (TJ-45) and its components on rat pancreatic acinar cell injuries in vivo and in vitro. Pancreatology 2001, 1, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimitsu, A.; Tojo, A.; Satonaka, H.; Ishimitsu, T. Eucommia ulmoides (Tochu) and its extract geniposidic acid reduced blood pressure and improved renal hemodynamics. Biomed Pharm. 2021, 141, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M. Oriental medical research on neurosis Part 3: Clinical trials and discussion of blood paths. Nitto Med. J. 1961, 12, 14–19. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakakubo, S.; Kimura, S.; Mimura, K.; Kajiwara, C.; Ishii, Y.; Konno, S.; Tateda, K. Traditional Japanese Herbal Medicine Hochu-Ekki-to Promotes Pneumococcal Colonization Clearance via Macrophage Activation and Interleukin 17A Production in Mice. Front Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 569158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, S.; Abe, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Liu, S.-Y. Inhibition of the formation of oral calcium phosphate precipitates: Beneficial effects of Chinese traditional (kampo) medicines. J. Periodontal Res. 1993, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakasugi, A.; Odaguchi, H.; Oikawa, T.; Hanawa, T. Effects of goshuyuto on lateralization of pupillary dynamics in headache. Auton Neurosci. 2008, 139, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Takahara, C.; Tabuchi, N.; Okamura, N. Daiokanzoto (Da-Huang-Gan-Cao-Tang) is an effective laxative in gut microbiota associated with constipation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmananda, S. The Practice of Chinese Herbal Medicine in Japan. Available online: http://www.itmonline.org/arts/kampo.htm (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. The Contribution of Jian Zhen’s East-Crossing to Japan Medicine from Perspective of Chinese Medicine Dissemination to West Countries. Tradit. Chin. Med. Res. 2018, 4, 6–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mayanagi, M. A basic research on the vol. 30 of the “Ishinho” On historical and herbological. Yakushigaku Zasshi 1986, 21, 51–59. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Daren, S. A research on the historical sites of medicine by the monk Jianzhen: Commemorating the 1226th anniversary of the monk Jianzhen’s eastward crossing. J. Zhejiang Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1979, 2, 67–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, S. A gambir recipe brought by Ganjin, a Chinese buddhist dignitary. Yakushigaku Zasshi. 2005, 40, 22–24. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y. Three Treasures Be Published; Shidai Wenxian (Time and Literature) Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, T. Reviving Toshodaiji’s Herb Garden, Jianzhen’s Scent, to Be Completed in 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASPDG6S31PDFPOMB01H.html (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Dotoku, K. Past Masterpieces in Pharmacy. Pharm. Libr. 1999, 44, 149–154. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Huang, H.; Sasaki, H.; Takeda, O.; Higuchi, T.; Mukita, Y.; Mori, Y.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shiratori, M. Survey report on the amount of crude drug used in Japan. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019, 73, 16–35. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, T.; Sakai, E.; Makino, T. Textbook of Pharmacognosy, 9th ed.; Nankodo Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2021; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Pei, J. Innovating Chinese Herbal Medicine: From Traditional Health Practice to Scientific Drug Discovery. Front Pharm. 2017, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall A., C. Traditional Chinese Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology. Drug Discov. Eval. Methods Clin. Pharm. 2020, 2, 455–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wertz, S.K. The Elements of Taste: How Many Are There? J. Aesthetic Educ. 2013, 47, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Luo, Q.; Sun, M.; Corke, H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2157–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Jia, C.; Guo, J.; Gu, H.; Miao, Y. Features analysis of five-element theory and its basal effects on construction of visceral manifestation theory. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 34, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-Y. A contribution to our knowledge of ginseng. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1977, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.angelo.edu/faculty/kboudrea/index_2353/Chapter_01_2SPP.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Available online: https://support-center.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SupportCenter/en/room03 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Crump, A.; Ōmura, S. Ivermectin, ‘wonder drug’ from Japan: The human use perspective. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2011, 87, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.-Z.; Miller, L.-H. The discovery of artemisinin and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Sci. China. Life Sci. 2015, 58, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Qi, J.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Xia, X.; Dou, H.; Hou, Y. Protective Effect of Dihydroartemisinin in Inhibiting Senescence of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells From Lupus Mice via Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Xiao, L.; Gu, F.; Huang, J.; Tsao, B.P.; Sun, L. Artesunate inhibits type I interferon-induced production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2016, 26, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.-L.; Zhang, A.-H.; Wang, X.-J. Traditional Chinese Medicine for COVID-19 treatment. Pharm. Res. 2020, 155, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, M.; Fan, G.; Xiao, G.; Wang, T.; Xu, D.; Gao, J.; Ge, S.; Li, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine in COVID-19. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2021, 11, 3337–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, S.; Namiki, T.; Odaguchi, H.; Arita, R.; Hisanaga, A.; Mitani, K.; Ito, T. Prevention and Recovery of COVID-19 Patients With Kampo Medicine: Review of Case Reports and Ongoing Clinical Trials. Front Pharm. 2021, 12, 656246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, X. The study of the effect of Chinese medicine Lingqi Huangban granules in the treatment of patients with ischemic retinal vein occlusion without macular edema. China J. Chin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 28, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Multi-target treatment of fundus hemorrhagic diseases. China J. Chin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 29, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Unschuld, P.U. The past 1000 years of Chinese medicine. Lancet 1999, 354, SIV9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.-J.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Yao, C.-L.; Bauer, R.; Khan, I.A.; Wu, W.-Y.; Guo, D.-A. Deeper Chemical Perceptions for Better Traditional Chinese Medicine Standards. Engineering 2019, 5, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; David, B.; Tu, P.; Barbin, Y. Recent analytical approaches in quality control of Traditional Chinese Medicines-a review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 657, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Bai, H.; Ning, K. Network Pharmacology Databases for Traditional Chinese Medicine: Review and Assessment. Front Pharm. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.-F.; Zhou, W.-J.; Wu, R.; Su, S.-B. Systems biology approaches in the study of Chinese herbal formulae. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.J.; Buriani, A.; Ehrman, T.; Bosisio, E.; Eberini, I.; Hylands, P.J. In-silico studies in Chinese herbal medicines’ research: Evaluation of in-silico methodologies and phytochemical data sources, and a review of research to date. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, H.; Chen, J.; Ji, D.; Mao, C.; Lu, T. A Modern Technology Applied in Traditional Chinese Medicine: Progress and Future of the Nanotechnology in TCM. Dose Response. 2019, 17, 1559325819872854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).