Natural or Violent Death? Deceptive Crime Scene in a Case of Ruptured Varicose Vein

Abstract

1. Introduction

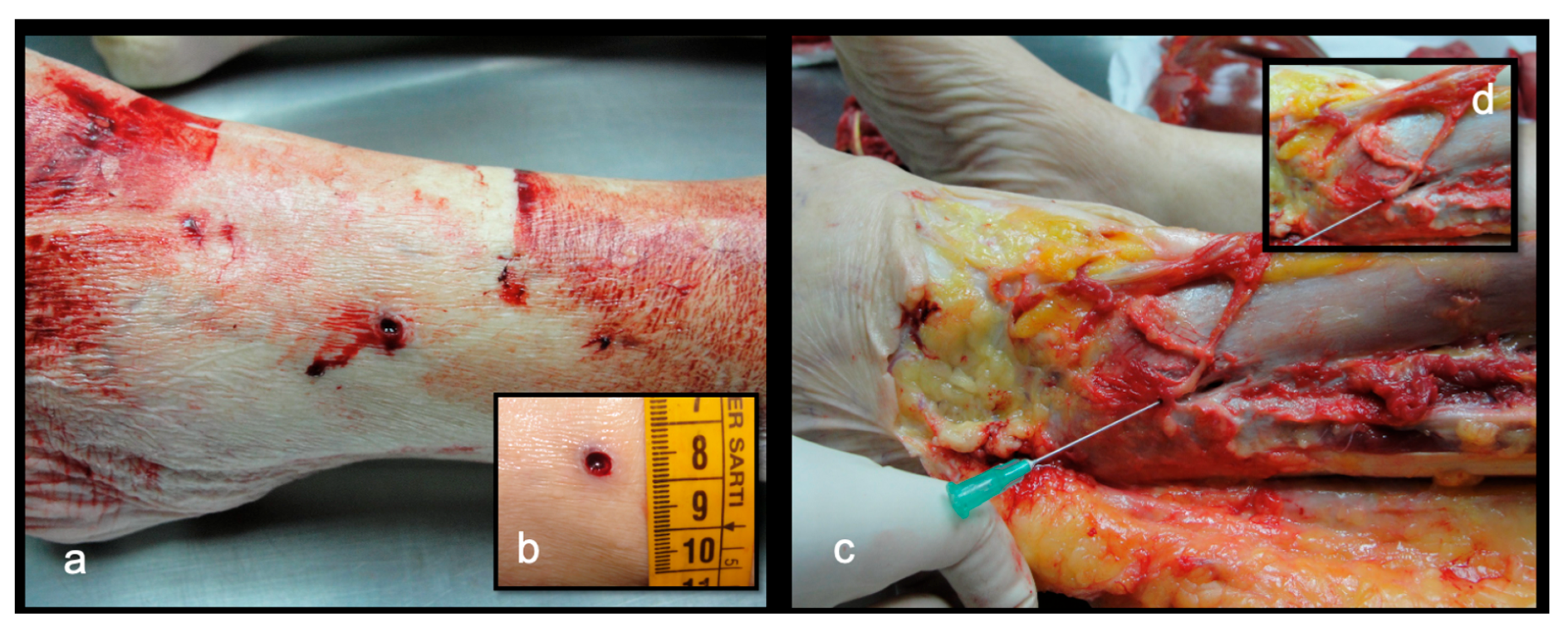

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teiteilbaum, G.P.; Davis, P.S. Spontaneous rupture of a lower extremity varix: Case report. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 1989, 12, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, R.W.; Gilbert, J.D. The incidence and characteristic features of fatal hemorrhage due to ruptured varicose veins: A 10-year autopsy study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2007, 28, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittadini, F.; Albertacci, G.; Pascali, V.L. Unattended fatal hemorrhage caused by spontaneous rupture of a varicose vein. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2008, 29, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.; Tambuzzi, S.; Boracchi, M.; Gobbo, A.D.; Bailo, P.; Zoia, R. Fatal hemorrhage from peripheral varicose vein rupture. Autops. Case Rep. 2021, 11, e2021330, Erratum in Autops. Case Rep. 2022, 12, e2021367. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2021.367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, J.; Nakajima, H.; Nakata, M.; Fukuhara, A.; Kang, J.; Yasue, Y. Near—Fatal bleeding due to ruptured peripheral varicose vein that developed after previous orthopedic surgery: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfisterer, L.; König, G.; Hecker, M.; Korff, T. Pathogenesis of varicose veins—Lessons from biomechanics. VASA Z. Gefasskrankh. 2014, 43, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansilvestri-Morel, P.; Fioretti, F.; Rupin, A.; Senni, K.; Fabiani, J.N.; Godeau, G.; Verbeuren, T.J. Comparison of extracellular matrix in skin and saphenous veins from patients with varicose veins: Does the skin reflect venous matrix changes? Clin. Sci. 2007, 112, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.S.; Davies, A.H. Pathogenesis of primary varicose veins. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocker, D.M.; Nyamekye, I.K. Fatal haemorrhage from varicose veins: Is the correct advice being given? J. R. Soc. Med. 2008, 101, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberentz, E.; Hagemeier, L.; Veit, C.; Madea, B. Unattended fatal haemorrhage due to spontaneous peripheral varicose vein rupture—Two case reports. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 206, e12–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvageau, A.; Schellenberg, M.; Racette, S.; Julien, F. Bloodstain pattern analysis in a case of fatal varicose vein rupture. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2007, 28, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragkouli, K.; Mitselou, A.; Boumba, V.A.; Siozios, G.; Vougiouklakis, G.T.; Vougiouklakis, T. Unusual death due to a bleeding from a varicose vein: A case report. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handlos, P.; Handlosová, K.; Klabal, O.; Uvíra, M. A rare suicide case involving fatal bleeding from varicose veins. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 2020–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saukko, P.; Knight, B. Knight’s Forensic Pathology, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, R.; Ielapi, N.; Bevacqua, E.; Rizzuto, A.; De Caridi, G.; Massara, M.; Casella, F.; Di Mizio, G.; de Franciscis, S. Haemorrhage from varicose veins and varicose ulceration: A systematic review. Int. Wound J. 2018, 15, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe-Dimmer, J.L.; Pfeifer, J.R.; Engle, J.S.; Schottenfeld, D. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Machin, M.; Patterson, B.O.; Onida, S.; Davies, A.H. Global epidemiology of chronic venous disease: A systematic review with pooled prevalence analysis. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H.; Heo, S. Varicose veins and the diagnosis of chronic venous disease in the lower extremities. J. Chest Surg. 2024, 57, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinelli, S.; Bonaccorso, L.; Gitto, L. Fatal bleeding caused by a ruptured varicose vein. Med. Leg. J. 2020, 88, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquila, I.; Sacco, M.A.; Gratteri, S.; Di Nunzio, C.; Ricci, P. Sudden death by rupture of a varicose vein: Case report and review of literature. Med. Leg. J. 2017, 85, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampanozi, G.; Preiss, U.; Hatch, G.M.; Zech, W.D.; Ketterer, T.; Bolliger, S.; Thali, M.J.; Ruder, T.D. Fatal lower extremity varicose vein rupture. Leg. Med. 2011, 13, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassina, G.; Rigato, S.; Fassan, M.; Rotter, G.; Sanavio, M.; Cecchetto, G.; Viel, G. A case of lethal varicose vein rupture caused by massive leiomyoma. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 328, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, A.C.; Baronti, A.; Bosetti, C.; Costantino, A.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Maiese, A. Bleeding varicose veins’ ulcer as a cause of death: A case report and review of the current literature. Clin. Ter. 2021, 172, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mileva, B.; Tsranchev, I.; Angelov, M.; Brainova, I.; Georgieva, M.; Peev, K.; Alexsandrov, A.; Jelev, L.; Goshev, M. Homicide or a Sudden Death? Rupture of Varicose Veins—Case Report. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 31, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigle, R.L.; Anderson, G.V., Jr. Exsanguinating hemorrhage from peripheral varicosities. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1988, 17, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y. A case of life-threatening hemorrhagic shock due to spontaneous rupture of a leg varicose vein. J. Rural. Med. 2012, 7, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.D.; Byard, R.W. Ruptured varicose veins and fatal hemorrhage. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2018, 14, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, P. A case of fatal spontaneous varicose vein rupture—An example of incorrect first aid. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 1146–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, R.; Cusack, D.; Ludes, B.; Madea, B.; Vieira, D.N.; Keller, E.; Payne-James, J.; Sajantila, A.; Vali, M.; Gherardi, M.; et al. European Council of Legal Medicine (ECLM) on-site inspection forms for forensic pathology, anthropology, odontology, genetics, entomology and toxicology for forensic and medico-legal scene and corpse investigation: The Parma form. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2022, 136, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camatti, J.; Santunione, A.L.; Bolognini, M.; Cusack, D.; Zerbo, S.; Argo, A.; Puntarello, M.; Scalzo, G.; Paolo, F.; Bruscagin, T.; et al. Towards a standard of scientific evidence in on-site inspection: Compilation of the ECLM on-site inspection form in a broad case history. Leg. Med. 2025, 78, 102717. [Google Scholar]

- Stassi, C.; Mondello, C.; Baldino, G.; Cardia, L.; Gualniera, P.; Calapai, F.; Sapienza, D.; Asmundo, A.; Ventura Spagnolo, E. State of the art on the role of postmortem computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of cardiac causes of death: A narrative review. Tomography 2022, 8, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, G.; Mondello, C.; Sapienza, D.; Stassi, C.; Asmundo, A.; Gualniera, P.; Vanin, S.; Ventura Spagnolo, E. Multidisciplinary Forensic Approach in “Complex” Bodies: Systematic Review and Procedural Proposal. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, G.; Raffino, C.; Burrascano, G.; Ventura Spagnolo, E.; Baldino, G.; Asmundo, A. The Role of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) in Reconstructing the Dynamics of Forensic Cases. Clin. Ter. 2024, 175 (Suppl. S2), 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, S.; Zivkovic, V. Bloodstain pattern in the form of gushing in a case of fatal exsanguination due to ruptured varicose vein. Med. Sci. Law 2011, 51, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, B.E.; Sullivan, L.M.; Adams, S.; Middleberg, R.A.; Wolf, B.C. Multidisciplinary investigation of an unusual apparent homicide/suicide. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2011, 32, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baldino, G.; Tarzia, P.; Rotter, G.; Calabrese, S.; Čaplinskienė, M.; Ventura Spagnolo, E. Natural or Violent Death? Deceptive Crime Scene in a Case of Ruptured Varicose Vein. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040070

Baldino G, Tarzia P, Rotter G, Calabrese S, Čaplinskienė M, Ventura Spagnolo E. Natural or Violent Death? Deceptive Crime Scene in a Case of Ruptured Varicose Vein. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldino, Gennaro, Pietro Tarzia, Gabriele Rotter, Simona Calabrese, Marija Čaplinskienė, and Elvira Ventura Spagnolo. 2025. "Natural or Violent Death? Deceptive Crime Scene in a Case of Ruptured Varicose Vein" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040070

APA StyleBaldino, G., Tarzia, P., Rotter, G., Calabrese, S., Čaplinskienė, M., & Ventura Spagnolo, E. (2025). Natural or Violent Death? Deceptive Crime Scene in a Case of Ruptured Varicose Vein. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040070