The Risk Factors of Chronic Pain Checklist (RFCP-CK): A New Screening and Assessment Tool for Victims of Violence and Non-Victims

Abstract

1. Introduction

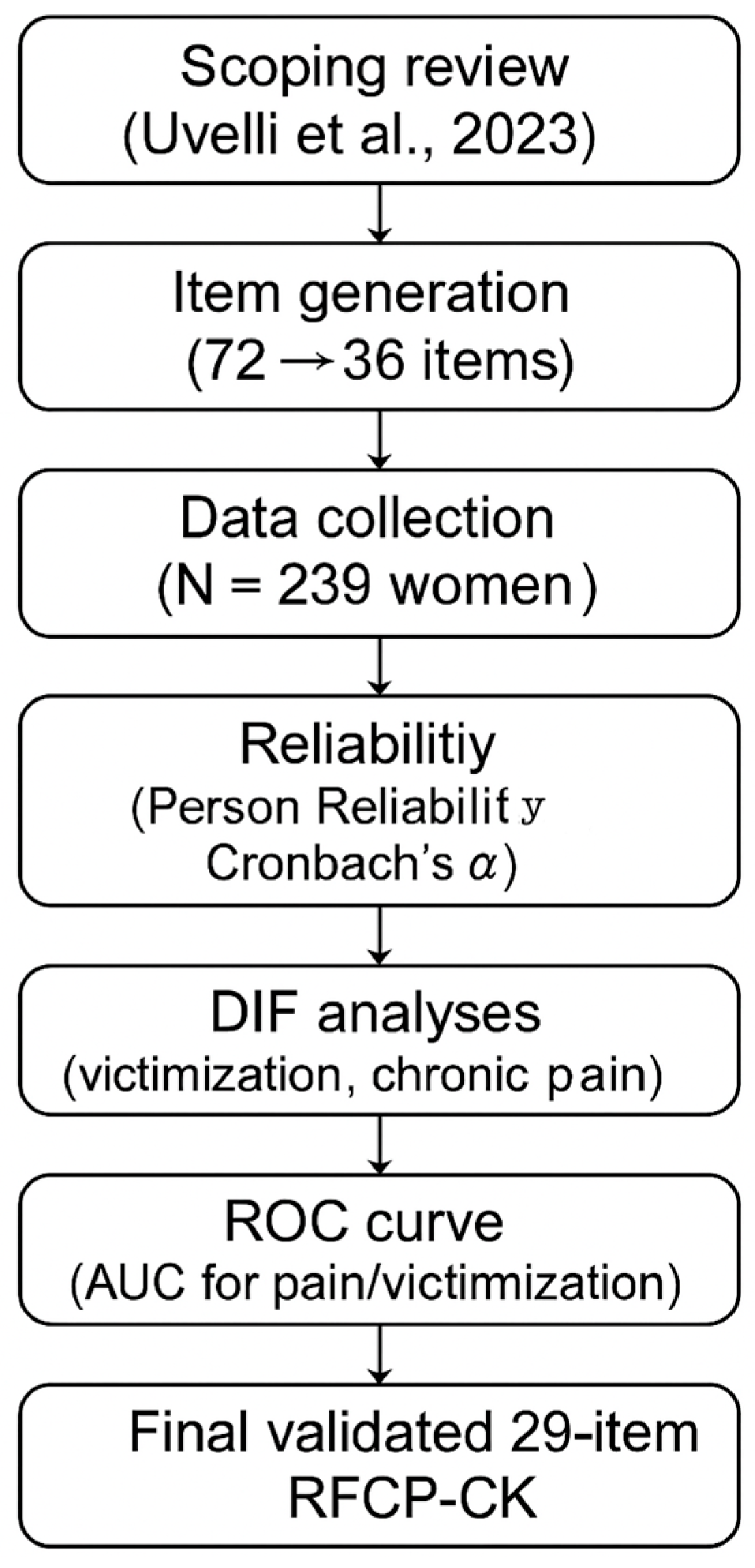

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measure

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

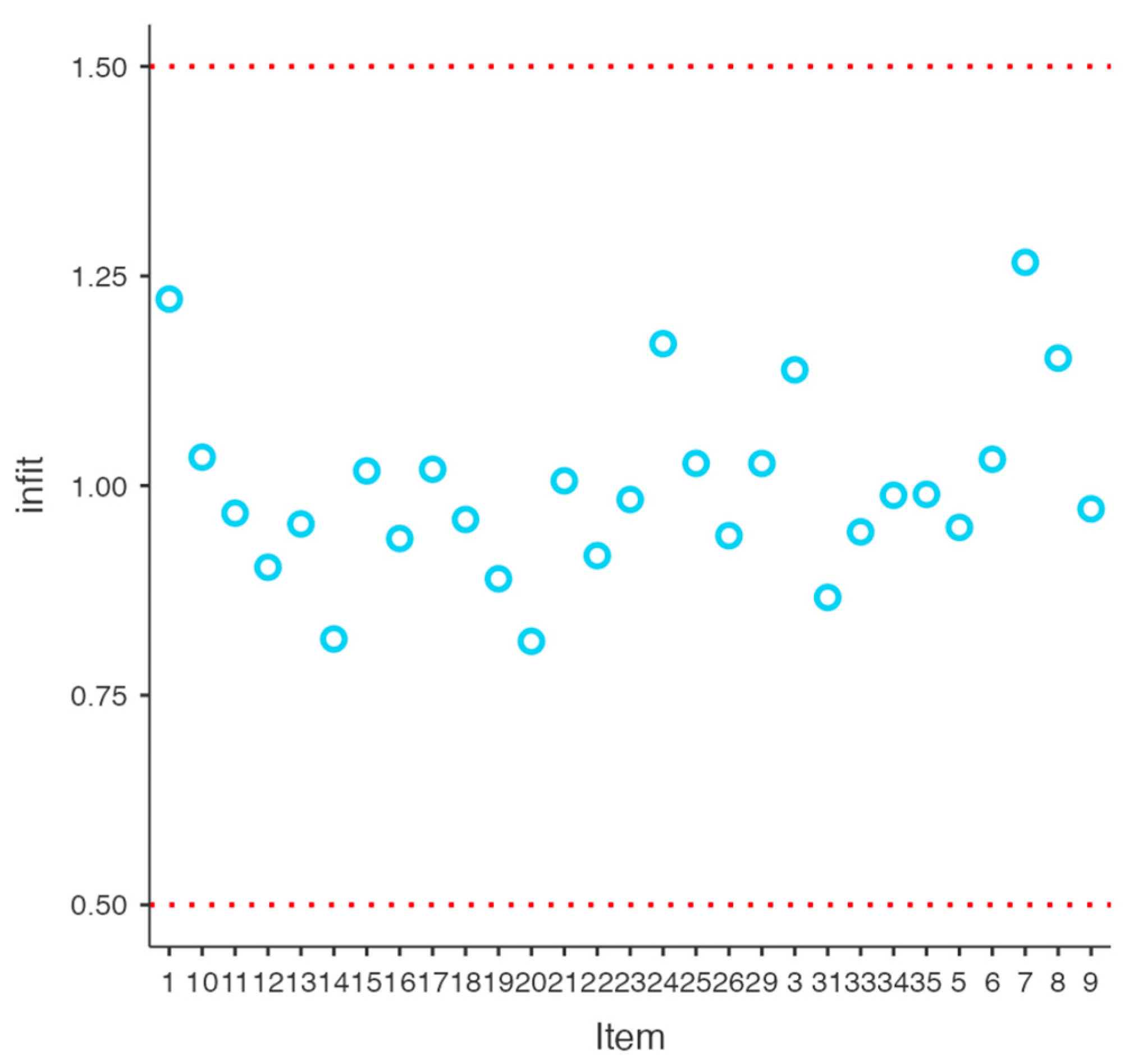

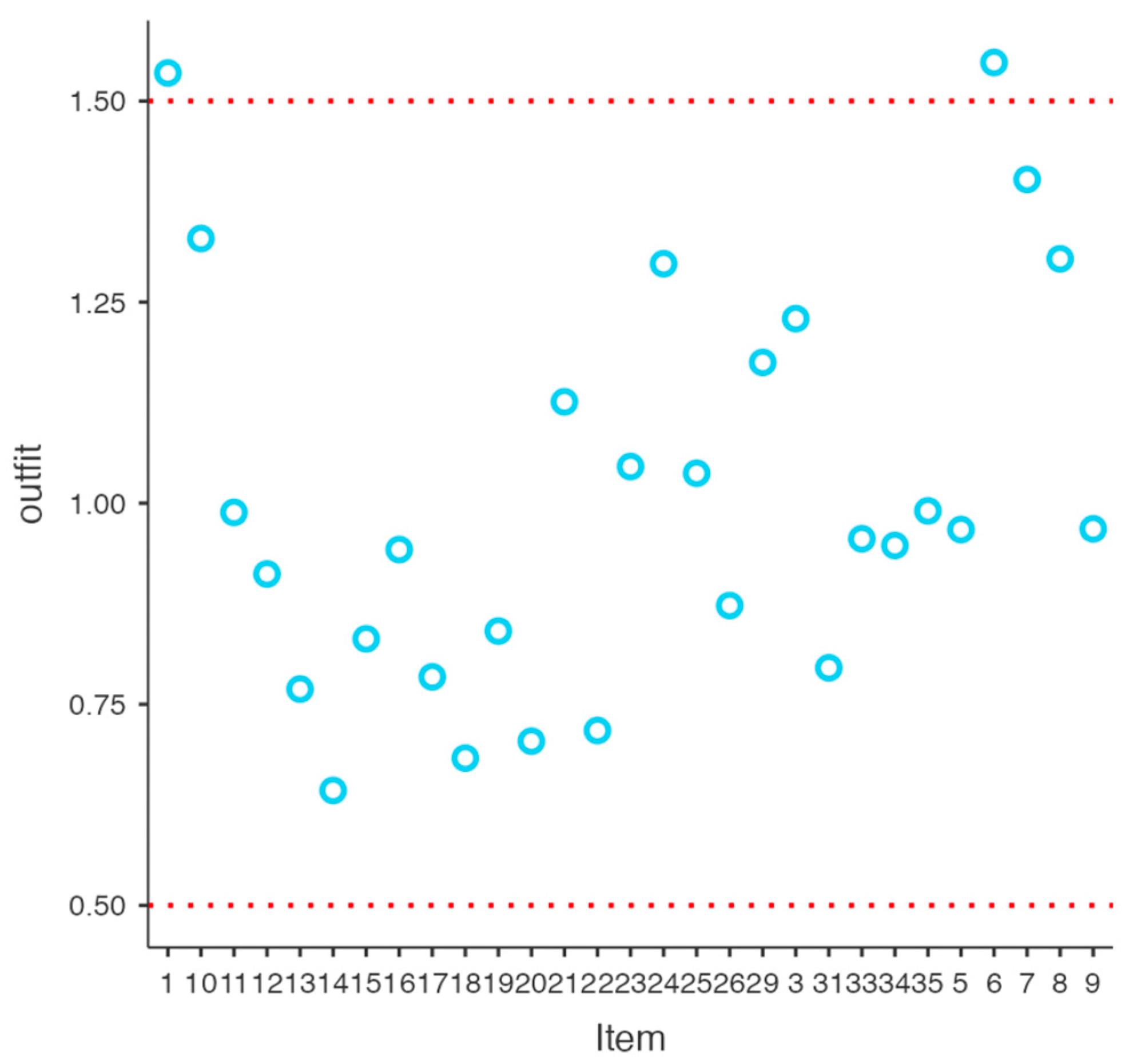

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

3.3. Correlation Analyses and Differential Item Functioning

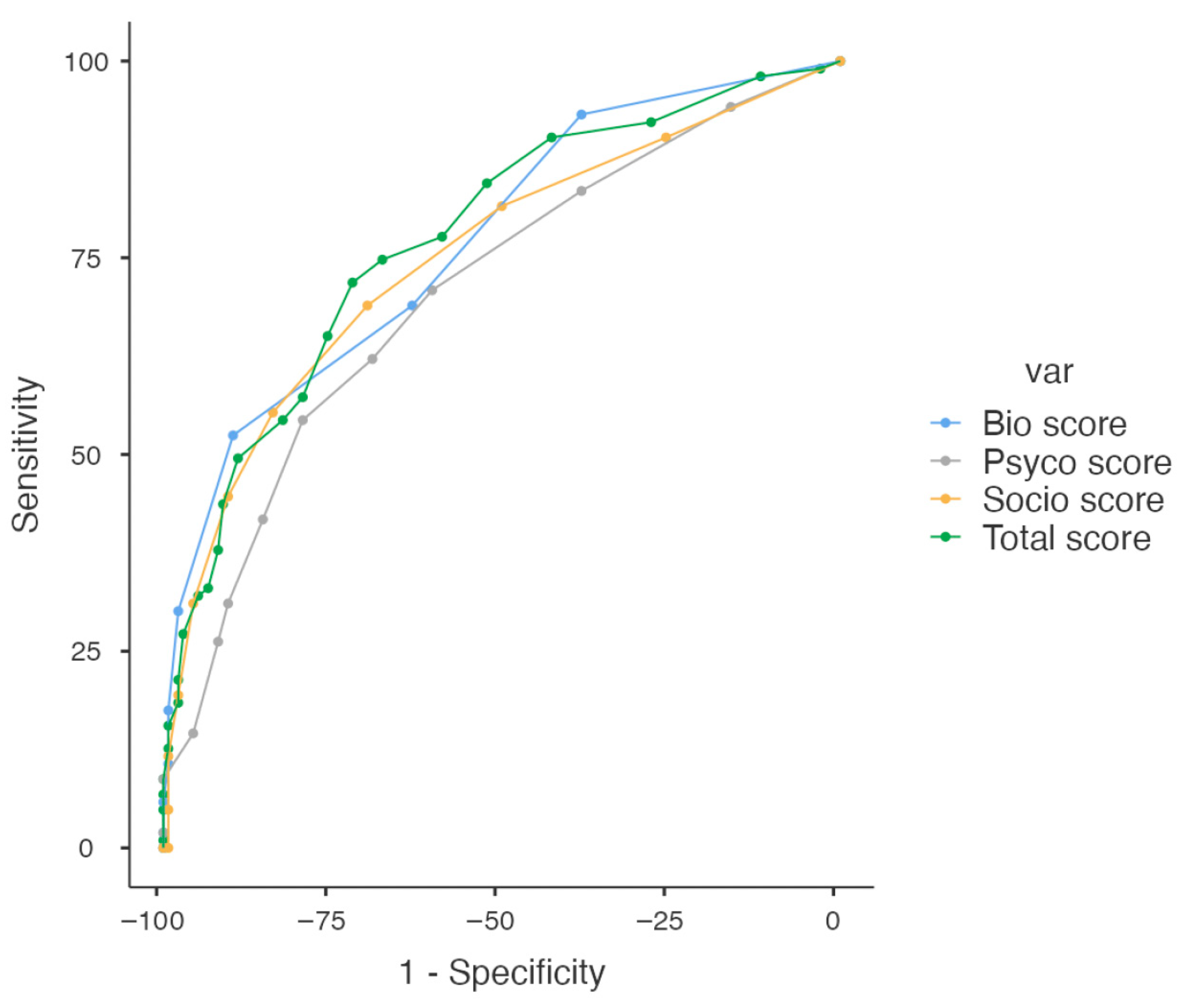

3.4. ROC Curve Analyses

3.5. Intercorrelations and Scores

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| BIO-PSYCHO-SOCIAL Categories | YES | NO |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Recurrent respiratory infections (sinusitis, nasal congestion) | ||

| 2. Allergies resulting in respiratory symptoms (asthma, allergic rhinitis) | ||

| 3. Recurrent urinary infections (cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis) | ||

| 4. Vaginal swelling | ||

| 5. Heart palpitations | ||

| 6. Lipid metabolism disorder | ||

| 7. Recurrent alterations of intestinal transit (constipation, diarrhea) | ||

| 8. Skin problems/irritations (dermatitis, eczema, rush) | ||

| 9. Muscle inflammation | ||

| 10. Osteoarthritis | ||

| 11. Sleep disorders (insomnia, hypersomnia) | ||

| 12. Anxiety disorder (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia) | ||

| 13. Mood disorder (depression, bipolar disorder) | ||

| 14. Post-Traumatic stress disorder | ||

| 15. Somatic disorder (somatic symptoms, hypochondria, conversion disorder) | ||

| 16. Request for a medical advice for a disorder without receiving assistance for it | ||

| 17. Diagnosis of any psychological disorder | ||

| 18. Single sexual abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years) | ||

| 19. Recurrent physical abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years) | ||

| 20. Recurrent psychological abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years) | ||

| 21. Single physical abuse during childhood (<18 years) | ||

| 22. Recurrent psychological abuse during childhood (<18 years) | ||

| 23. Traumatic experiences during childhood endured or witnessed | ||

| 24. Traumatic experiences in adulthood endured or witnessed | ||

| 25. Tense relationships within the family of origin | ||

| 26. Tense relationships within the current family unit | ||

| 27. Good relationship with parents | ||

| 28. Satisfaction for one’s life as it is | ||

| 29. High stress levels | ||

| 30. Recurrent suicidal thoughts | ||

| 31. Recurring feelings of guilt and shame | ||

| 32. Getting support in case of need | ||

| 33. Impediment in carrying out normal daily activities due to pain | ||

| 34. Tiredness/absence of energy even in the early morning | ||

| 35. High emotionality (very intense expression and experience of emotional states) | ||

| 36. More than 4 sexual partners during the course of life |

Appendix B

| Categorie BIO-PSICO-SOCIALI/ BIO-PSYCHO-SOCIAL Categories/ Categorías BIO-PSICO-SOCIAL | SI/Yes | NO |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Infezioni delle vie respiratorie ricorrenti (sinusiti, congestioni nasali)—Recurrent respiratory infections (sinusitis, nasal congestion)—Infecciones recurrentes del tracto respiratorio (sinusitis, congestión nasal) | ||

| 2. Infezioni delle vie urinarie ricorrenti (cistiti, uretriti, pielonefriti)—Recurrent urinary infections (cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis)—Infecciones recurrentes del tracto urinario (cistitis, uretritis, pielonefritis) | ||

| 3. Palpitazioni cardiache—Heart palpitations—Palpitaciones del corazón | ||

| 4. Disturbo del metabolismo dei lipidi—Lipid metabolism disorder—Trastorno del metabolismo de los lípidos | ||

| 5. Alterazioni ricorrenti nel transito intestinale (stitichezza, costipazione, diarrea)—Recurrent alterations of intestinal transit (constipation, diarrhea)—Alteraciones recurrentes en el tránsito intestinal (estreñimiento, diarrea) | ||

| 6. Problemi/irritazioni cutanee (dermatite, eczema, rash)—Skin problems/irritations (dermatitis, eczema, rush)—Problemas/irritaciones de la piel (dermatitis, eczema, erupción) | ||

| 7. Infiammazione muscolare—Muscle inflammation—Inflamación muscular | ||

| 8. Osteoartrite—Osteoarthritis—Osteoartritis | ||

| 9. Disturbi del sonno (insonnia, ipersonnia)—Sleep disorders (insomnia, hypersomnia)—Trastornos del sueño (insomnio, hipersomnia) | ||

| 10. Disturbo d’ansia (disturbo di panico, disturbo di ansia sociale, disturbo d’ansia generalizzato, fobia specifica)—Anxiety disorder (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia)—Trastorno d’ansiedad (trastorno de pánico, trastorno de ansiedad social, d’ansiedad generalizada, fobia específica) | ||

| 11. Disturbo dell’umore (depressione, disturbo bipolare)—Mood disorder (depression, bipolar disorder)—Perturbación de’estado de ánimo (depresión, trastorno bipolar) | ||

| 12. Disturbo da stress post-traumatico—Post-Traumatic stress disorder—Trastorno de estrés postraumático | ||

| 13. Disturbo somatico (sintomi somatici, ipocondria, disturbo di conversione)—Somatic disorder (somatic symptoms, hypochondria, convertion disorder)—Trastorno somático (síntomas somáticos, hipocondría, trastorno de conversión) | ||

| 14. Richiesta di parere medico per un disturbo senza poi ricevere assistenza per quello—Request for a medical advice for a disorder without receiving assistance for it—Solicitar consejo médico para un trastorno sin recibir luego asistencia para ello | ||

| 15. Diagnosi di qualsiasi disturbo psicologico—Diagnosis of any psychological disorder—Diagnóstico de cualquier trastorno psicológico | ||

| 16. Singolo abuso sessuale da parte del partner durante l’età adulta (>18 anni)—Single sexual abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years)—Abuso sexual individual por parte de la pareja durante su edad adulta (>18 años) | ||

| 17. Ricorrenti abusi fisici da parte del partner durante l’età adulta (>18 anni)—Recurrent physical abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years)—Abuso físico recurrente por parte de la pareja durante el embarazo (>18 años) | ||

| 18. Ricorrenti abusi psicologici da parte del partner durante l’età adulta (>18 anni)—Recurrent psychological abuse by your partner at adult age (>18 years)—Abuso psicológico recurrente por parte de la pareja durante su edad adulta (>18 años) | ||

| 19. Singolo abuso fisico durante l’infanzia (<18 anni)—Single physical abuse during childhood (<18 years)—Abuso físico único durante infancia (<18 años) | ||

| 20. Ricorrenti abusi psicologici durante l’infanzia (<18 anni)—Recurrent psychological abuse during childhood (<18 years)—Abuso psicológico recurrente durante infancia (<18 años) | ||

| 21. Esperienze traumatiche durante l’infanzia subite o assistite (lutti, incidenti, violenza assistita, gravi malattie, guerra)—Traumatic experiences during childhood endured or witnessed (be reavement, accidents, assisted violence, serious illnesses, war)—Experiencias traumáticas durante infancia sufrida o presenciada (duelo, accidentes, violencia presenciada, enfermedades graves, guerra) | ||

| 22. Esperienze traumatiche durante l’età adulta subite o assistite (lutti, incidenti, violenza, gravi malattie, guerra)—Traumatic experiences in adulthood endured or witnessed (be reavement, accidents, violence, serious illnesses, war)—Experiencias traumáticas durante edad adulta sufrido o presenciado en la edad adulta (muerte, accidentes, violencia presenciada, enfermedades graves, guerra) | ||

| 23. Rapporti tesi all’interno della famiglia di origine—Tense relationships within the family of origin—Relaciones tensas dentro de la familia de origen | ||

| 24. Rapporti tesi all’interno dell’attuale nucleo familiare—Tense relationships within the current family unit—Relaciones tensas en todo el interior de la unidad familiar actual | ||

| 25. Elevati livelli di stress—High stress levels—Altos niveles de estrés | ||

| 26. Ricorrenti sentimenti di colpa e vergogna—Recurring feelings of guilt and shame—Sentimientos recurrentes de culpa y vergüenza | ||

| 27. Impedimento nello svolgimento di normali attività quotidiane a causa di dolore—Impediment in carrying out normal daily activities due to pain—Impedimento para realizar actividades normales adiariamente debido al dolor | ||

| 28. Stanchezza/assenza di energie anche di prima mattina—Tiredness/absence of energy even in the early morning—Cansancio/falta de energía incluso temprano en la mañana | ||

| 29. Elevata emotività (espressione ed esperienza degli stati emotivi molto intensa)—High emotionality (very intense expression and experience of emotional states)—Alta emocionalidada (expresión y experiencia muy intensa de estados emocionales) |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). IPV Definition, Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Uvelli, A.; Floridi, M.; Agrusti, G.; Franquillo, A.C.; Fiumalbi, L.; Micheloni, T.; Arcuri, A.; Iazzetta, S.; Gragnani, A. When adverse experiences influence the interpretation of ourselves, others and the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of maladaptive schemas in victims of violence. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Kearns, M.C.; McIntosh, W.L.; Estefan, L.F.; Nicolaidis, C.; McCollister, K.E.; Gordon, A.; Florence, C. Lifetime Economic Burden of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, S.; Khalifeh, H.; Howard, L.M. Violence against women and mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.A.; Young, J.M.; Rae, H.; Jalaludin, B.B.; Solomon, M.J. Factors associated with back pain after physical injury: A survey of consecutive major trauma patients. Spine 2007, 32, 1561–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvelli, A.; Ribaudo, C.; Gualtieri, G.; Coluccia, A.; Ferretti, F. The association between violence against women and chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magariños López, M.; Lobato Rodríguez, M.J.; Menéndez García, Á.; García-Cid, S.; Royuela, A.; Pereira, A. Psychological Profile in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunduz, N.; Erzican, E.; Polat, A. The relationship of intimate partner violence with psychiatric disorders and severity of pain among female patients with fibromyalgia. Arch. Rheumatol. 2019, 34, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, X.; Xuan, L.; Wang, J.; Zhan, T.; Chen, Y.; Xu, S.; Ji, D. The interaction effect between childhood trauma and negative events during adulthood on development and severity of irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, M.; Canavese, A.; Magnano, L.; Rondana, A.; Castagna, P.; Gino, S. Violence against pregnant women in the experience of the rape centre of Turin: Clinical and forensic evaluation. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2020, 76, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, J.S.; Thomas, T.; Bradbury-Jones, C.; Taylor, J.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Nirantharakumar, K. Intimate partner violence and temporomandibular joint disorder. J. Dent. 2019, 82, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajah, R.; Welkie, J.; Mack, J.; Casas, R.S.; Paulishak, M.; Chetlen, A.L. A review of breast pain: Causes, imaging recommendations, and treatment. J. Breast Imaging 2020, 2, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greger, H.K.; Kristianslund, S.K.; Stensland, S.Ø. Interpersonal violence and recurrent headache among adolescents with a history of psychiatric problems. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, D.; Van Wersch, A.; Carthy, N. ‘It’s like drowning and you can’t get out’; the influence of intimate partner violence on women with chronic low back pain. Eur. J. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.B.; Corey, T.S.; Weakley-Jones, B.; Stewart, D. Living victims of strangulation: A 10-year review of cases in a metropolitan community. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2010, 31, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casale, R.; Atzeni, F.; Bazzichi, L.; Beretta, G.; Costantini, E.; Sacerdote, P.; Tassorelli, C. Pain in women: A perspective review on a relevant clinical issue that deserves prioritization. Pain Ther. 2021, 10, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N.R.; Davis, K.D. Sex and gender differences in pain. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2022, 164, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarty, M.; Singh, A.; Mohan, D.; Singh, S. Understanding the association between intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted infections among women in India: A propensity score matching approach. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2024, 100, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, W.F.; Coelho, D.R.A.; Litwiler, S.T.; McEachern, K.M.; Clancy, J.A.; Morales-Quezada, L.; Cassano, P. Neuropathic pain, mood, and stress-related disorders: A literature review of comorbidity and co-pathogenesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 161, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.K.Y.; Lereya, S.T.; Boulton, H.; Miller, M.A.; Wolke, D.; Cappuccio, F.P. Nonpharmacological treatments of insomnia for long-term painful conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials. Sleep 2015, 38, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rometsch, C.; Martin, A.; Junne, F.; Cosci, F. Chronic pain in European adult populations: A systematic review of prevalence and associated clinical features. Pain 2025, 166, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruddere, L.; Craig, K.D. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: A-state-of-the-art review. Pain 2016, 157, 1607–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvelli, A.; Pugliese, E.; Ferretti, F. Risk factors for chronic pain in women: The role of violence exposure in a case-control study. Life 2025, 15, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmer-Somers, K.; Vipond, N.; Kumar, S.; Hall, G. A review and critique of assessment instruments for patients with persistent pain. J. Pain Res. 2009, 2, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uvelli, A.; Pugliese, E.; Masti, A.; Salvo, G.; Duranti, C.; Gualtieri, G.; Ferretti, F. From the bio-psycho-social model to the development of a clinical forensic assessment tool for chronic pain in victims of violence: A research protocol. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvelli, A.; Duranti, C.; Salvo, G.; Coluccia, A.; Gualtieri, G.; Ferretti, F. The risk factors of chronic pain in victims of violence: A scoping review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D.; Linacre, J.M. Reasonable Mean-Square Fit Values. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 8, 370. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, M.; Sulaimanb, N.; Sern, L.; Sallehd, K. Measuring the validity and reliability of research instruments. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 204, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Zumbo, B.D. A Handbook on the Theory and Methods of Differential Item Functioning (DIF): Logistic Regression Modeling as a Unitary Framework for Binary and Likert-Type (Ordinal) Item Scores; Directorate of Human Resources Research and Evaluation, Department of National Defense: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 7, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.K.C.; Cheung, E.T.C.; Schoeb, V.; Opsommer, E.; Chong, D.Y.K.; Lee, J.L.C.; Kumlien, C.; Wong, A.Y.L. Lived Experiences of Older Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain and Implications on Their Daily Life: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Research. Arch. Rehab Res. Clin. Transl. 2025, 7, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martire, L.M.; Reis, H.T.; Felt, J.M.; Huang, Y. Relationship closeness in the context of chronic pain: Daily benefits and challenges for partners. Health Psychol. 2025, 44, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Ligero, M.; Salazar, A.; Failde, I.; Del Pino, R.; Coronilla, M.C.; Moral-Munoz, J.A. Factors associated with pain-related functional interference in people with chronic low back pain enrolled in a physical exercise programme: The role of pain, sleep, and quality of life. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, 38820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weib, M.; Jachnik, A.; Lampe, E.C.; Grundahl, M.; Harnik, M.; Sommer, C.; Rittner, H.L.; Hein, G. Differential effects of everyday-life social support on chronic pain. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, E.; Saliani, A.M.; Mosca, O.; Maricchiolo, F.; Mancini, F. When the War Is in Your Room: A Cognitive Model of Pathological Affective Dependence (PAD) and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Sustainability 2023, 15, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, E.; Uvelli, A.; van Emmerik, A.; Ferretti, F.; Saliani, A.M.; Foschino-Barbaro, M.G.; Vigilante, T.; Celitti, E.; Quintavalle, C.; Mancini, F.; et al. Pathological affective dependence as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: Initial psychometric validation of the Italian version of the pathological affective dependence scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. 2020. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GINA-2020-report_20_06_04-1-wms.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Bai, G.; Ren, K.; Dubner, R. Epigenetic regulation of persistent pain. Transl. Res. 2015, 165, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.Y.; Celedón, J.C. The effects of violence and related stress on asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 133, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okyere, J.; Ayebeng, C.; Dosoo, A.K.; Dickson, K.S. Association between experience of emotional violence and hypertension among Kenyan women. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.I.; Smyth, N.; Hall, S.J.; Torres, S.J.; Hussein, M.; Jayasinghe, S.U.; Ball, K.; Clow, A.J. Psychological stress reactivity and future health and disease outcomes: A systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 114, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassam, T.; Kelso, E.; Chowdary, P.; Yisma, E.; Mol, B.W.; Han, A. Sexual assault as a risk factor for gynaecological morbidity: An exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 255, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kim, N.; Suk, K.S.; Lee, B.H.; Bae, Y.; Park, M.; Ahn, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Moon, S.H.; et al. Increased risk of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic back pain following COVID-19 infection based on a nationwide population-based study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, C.P.; Gominho, M.; Arruda, G.A.; Bezerra, J.; Rangel, J.F.L.B.; Barros, M.V.G.; Santos, M.A.M.D. Associations between mental health and cervical, thoracic, and lumbar back pain in adolescents: A cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 375, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, R.V.; Ravyts, S.G.; Carnahan, N.D.; Bhattiprolu, K.; Harte, N.; McCaulley, C.C.; Vitalicia, L.; Rogers, A.B.; Wegener, S.T.; Dudeney, J. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Among Adults With Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlow, P.A.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Weissman, C.R.; Cha, D.S.; Kakar, R.; McIntyre, R.S.; Sharma, V. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and co-morbid bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinanes, Y.; Gonzalez-Villar, A.; Gomez-Perretta, C.; Carrillo-de-la-Pena, M.T. Suicidality in chronic pain: Predictors of suicidal ideation in fibromyalgia. Pain. Pract. 2015, 15, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.S.; Sami, N.; Saeed, A.A.; Ali, P. Gynaecological morbidities among married women and husband’s behaviour: Evidence from a community-based study. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, V.M.; Cankovic, S.; Milijasevic, D.; Ukropina, S.; Jovanovic, M.; Cankovic, D. Health consequences of domestic violence against women in Serbia. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2020, 77, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.; Beek, K.; Chen, H.; Shang, J.; Stevenson, S.; Williams, K.; Herzog, H.; Ahmed, J.; Cullen, P. The experiences of persistent pain among women with a history of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma. Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, K.M.; Rossi, F.S.; Nillni, Y.I.; Fox, A.B.; Galovski, T.E. PTSD and Depression Symptoms Increase Women’s Risk for Experiencing Future Intimate Partner Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgendorf, M.A.; Snipes, M.A.; O’Boyle, A.L. Prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence in a military urogynecology clinic. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, e1634–e1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nees, F.; Ditzen, B.; Flor, H. When shared pain is not half the pain: Enhanced central nervous system processing and verbal reports of pain in the presence of a solicitous spouse. Pain 2022, 163, e1006–e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, L.C.; Unahi, K.; Burrell, B.; Crowe, M.T. The experience of fatigue across long-term conditions: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2016, 52, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koechlin, H.; Coakley, R.; Schechter, N.; Werner, C.; Kossowsky, J. The role of emotion regulation in chronic pain: A systematic literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 107, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Victimization * | Age (Mean, SD) | Scholarship (Mean, SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain |

• 0 • 1 |

• 42.3 (12.7) • 46.8 (12.2) |

• 15.3 (3.71) • 14.5 (4.80) |

| Pain-free |

• 0 • 1 |

• 39.5 (13.1) • 40.2 (11.6) |

• 16.6 (4.32) • 16.2 (3.97) |

| Item | Proportion | Measure | S.E. Measure | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.22 | 1.65 | 0.17 | 1.22 | 1.53 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 2.09 | 0.19 | 1.13 | 1.22 |

| 5 | 0.28 | 1.21 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| 6 | 0.07 | 3.15 | 0.25 | 1.03 | 1.54 |

| 7 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 1.26 | 1.40 |

| 8 | 0.27 | 1.29 | 0.16 | 1.15 | 1.30 |

| 9 | 0.25 | 1.46 | 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| 10 | 0.12 | 2.55 | 0.21 | 1.03 | 1.32 |

| 11 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.15 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| 12 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| 13 | 0.23 | 1.58 | 0.17 | 0.95 | 0.76 |

| 14 | 0.22 | 1.65 | 0.17 | 0.81 | 0.64 |

| 15 | 0.19 | 1.91 | 0.18 | 1.01 | 0.83 |

| 16 | 0.20 | 1.81 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| 17 | 0.19 | 1.87 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 0.78 |

| 18 | 0.10 | 2.80 | 0.23 | 0.96 | 0.68 |

| 19 | 0.11 | 2.64 | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.84 |

| 20 | 0.29 | 1.15 | 0.16 | 0.81 | 0.70 |

| 21 | 0.08 | 3.03 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.12 |

| 22 | 0.17 | 2.02 | 0.19 | 0.91 | 0.71 |

| 23 | 0.31 | 1.02 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 1.04 |

| 24 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 1.29 |

| 25 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| 26 | 0.28 | 1.24 | 0.16 | 0.94 | 0.87 |

| 29 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 1.17 |

| 31 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| 33 | 0.24 | 1.49 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| 34 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| 35 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Person Reliability | MADaQ3 | p |

|---|---|---|

| 0.827 | 0.0746 | <0.001 |

| Value | DF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 70.0 | 27 | <0.001 |

| Pain | 72.4 | 28 | <0.001 |

| Victimization | 65.2 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Cutpoint: 8 | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | 87.5% | 76.82% | 0.643 | 0.90 |

| Pain | 71.84% | 72.06% | 0–439 | 0.774 |

| Total Score | Biological Score | Psychological Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological score | 0.72 *** | - | - |

| Psychological score | 0.91 *** | 0.52 *** | - |

| Social score | 0.89 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.73 *** |

| Biological Risk Factors (Mean, SD) | Psychological Risk Factors (Mean, SD) | Social Risk Factors (Mean, SD) | Total Score (Mean, SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.08 (1.85) | 3.41 (3.31) | 3.68 (2.40) | 9.17 (6.63) | ||

| Victimization | |||||

| Pain | • 0 • 1 | • 2.33 (1.69) • 3.72 (2.12) | • 2.27 (2.21) • 7.46 (2.60) | • 3.29 (2.23) • 6.02 (1.93) | • 7.88 (4.96) • 17.20 (5.43) |

| Pain-free | • 0 • 1 | • 1.14 (1.20) • 1.91 (1.22) | • 1.22 (1.38) • 5.24 (2.85) | • 2.39 (1.74) • 4.41 (2.03) | • 4.75 (3.29) • 11.60 (5.08) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uvelli, A.; Pugliese, E.; Ferretti, F. The Risk Factors of Chronic Pain Checklist (RFCP-CK): A New Screening and Assessment Tool for Victims of Violence and Non-Victims. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040063

Uvelli A, Pugliese E, Ferretti F. The Risk Factors of Chronic Pain Checklist (RFCP-CK): A New Screening and Assessment Tool for Victims of Violence and Non-Victims. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleUvelli, Allison, Erica Pugliese, and Fabio Ferretti. 2025. "The Risk Factors of Chronic Pain Checklist (RFCP-CK): A New Screening and Assessment Tool for Victims of Violence and Non-Victims" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040063

APA StyleUvelli, A., Pugliese, E., & Ferretti, F. (2025). The Risk Factors of Chronic Pain Checklist (RFCP-CK): A New Screening and Assessment Tool for Victims of Violence and Non-Victims. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040063