1. Introduction

Overkill in homicides lacks a universally accepted definition, creating challenges for forensic pathologists. While various definitions exist, consensus centers on violence exceeding that necessary to cause death. According to Taff & Boglioli [

1], overkill is generally defined as a phenomenon in which the multiplicity of wounds far outnumbers those required to cause death. Alternative definitions include those proposed by Strohm and Wolfgang, which establish criteria involving two or more separate actions of stabbing, cutting, or shooting, or severe beating during the victim’s slaying [

2]. Additionally, Tamsen et al. [

3] propose specific quantitative criteria: (1) A total of 40 or more skin injuries; (2) three or more sharp wounds located at the head, neck, or trunk with internal organ injuries; (3) three or more gunshot wounds located at the head, neck, or trunk with internal organ injuries.

The current forensic literature defines overkill as an arbitrarily applied descriptor for homicides characterized by an unusually high number of injuries, often inflicted with various instruments [

4].

The relationship between overkill and sexual homicide has been extensively documented. From a medicolegal and criminological perspective, in these cases typically there are bloody crime scenes with brutal victim injuries, often involving perpetrators with pre-existing relationships to victims. These characteristics are common in crimes of passion and may be linked to sexual motives [

5]. Sexual homicide cases present distinct patterns of overkill behavior that demonstrate significant heterogeneity in their behavioral manifestations. Research indicates that overkill occurs more frequently in sexual homicide cases compared to other homicide types, with Chopin and Beauregard [

6] finding that excessive violence and overkill behaviors were significantly overrepresented in cases involving sexual motivation. This suggests that the psychological drivers underlying sexual homicide create conditions that facilitate extreme violence beyond that necessary to cause death. The behavioral characteristics of overkill in sexual homicides have been associated with disorganized crime scene patterns. Ressler and colleagues’ seminal research on sexual killers [

7] identified that cases involving excessive violence often demonstrated disorganized behavioral patterns, including impulsive attack methods, chaotic crime scenes, and evidence of frenzied assault. These findings established that overkill in sexual contexts may reflect different psychological states and motivational frameworks compared to organized predatory behavior. Contemporary forensic research has further established connections between overkill behavior in sexual homicides and sadistic motivations [

8]. Sexual overkill encompasses cases where sadistic or paraphilic arousal contributes to the violence, with overkill serving both functional purposes (arousal or control) and symbolic purposes (humiliation or fantasy fulfillment). Wound patterns in these cases are characteristically targeted toward erogenous zones, and the violence often incorporates psychological dysfunction, fantasy reinforcement, and ritualistic elements [

9]. The complexity of sexual overkill is further complicated by necrophiliac and other unusual behaviors that may overlap with or obscure traditional overkill patterns. Recent research has identified a spectrum of extreme crime scene behaviors that extend beyond conventional overkill definitions, including cannibalism, evisceration, skinning, carving on victims, and vampirism. Sun et al. [

10] demonstrated that these unusual acts, while rare, represent a distinct crime-commission process characterized by higher levels of sadism and organization compared to typical overkill scenarios. Their analysis of 762 sexual homicide cases revealed that such behaviors are strongly associated with body dismemberment, foreign object insertion, and methodical post-mortem activities, suggesting that these extreme manifestations may represent an evolved form of overkill behavior rather than separate phenomena. These findings highlight the need for more nuanced frameworks to accommodate the spectrum of extreme violence observed in sexual homicide cases. The identification of these unusual acts as potential indicators of organized, sadistic behavior patterns provides important investigative insights while simultaneously complicating the standardized application of overkill criteria across diverse case presentations.

The critical challenge in overkill research lies in its operationalization and reliable identification across cases rather than in its conceptualization. Trojan et al. [

11] demonstrated that the term overkill has achieved widespread acceptance in homicide vernacular yet remains problematic due to a lack of concrete and objective definitions that impede proper operationalization and complicate replication across studies. The authors identified fundamental definitional issues ranging from broad conceptualizations to more specific criteria. Importantly, while overkill may be observed in serial homicide cases, these phenomena are not synonymous. Overkill represents a specific pattern of excessive violence that can occur in various homicide contexts, including but not limited to serial killing. Serial homicide is defined by the temporal and behavioral patterns of multiple murders committed by the same perpetrator over time, which may or may not involve overkill behavior in individual cases. This distinction is fundamental to understanding that the present analysis focuses specifically on the manifestation of excessive violence rather than serial killing behavior.

Beyond sexual overkill, contemporary research has identified distinct typological categories of overkill based on underlying motivational frameworks and behavioral patterns, as shown in

Table 1. According to Chatzinikolaou et al. [

9], these classifications provide crucial insights for forensic investigators in understanding the psychological and situational factors that contribute to excessive violence in homicidal contexts.

Expressive overkill represents the most documented form, characterized by homicides in which excessive violence stems from intense emotional arousal. This category typically involves emotionally charged relationships between perpetrators and victims, such as intimate partners, family members, or close friends, with violence manifesting through impulsive, unplanned attacks within domestic settings. Key forensic characteristics include the impulsive nature of the attack lacking premeditation, the use of improvised weapons based on availability, injury patterns typically localized in vital areas such as the face, neck, or chest, and evidence of symbolic violence. Perpetrators often demonstrate emotional dysregulation, may confess spontaneously, remain at the scene without attempting to conceal evidence, and frequently show remorse or even attempt suicide following the act.

Instrumental overkill describes extremely violent homicides motivated by specific goals such as robbery, financial gain, or revenge. While overkill is less commonly reported in these contexts, excessive violence may result from loss of control or situational escalation during premeditated acts. These homicides typically involve more calculated approaches by offenders with criminal or psychopathic traits who demonstrate no emotional ties to victims. In these cases, excessive violence often represents an unintended outcome rather than the primary objective.

Psychotic overkill manifests as disorganized attacks linked to delusional ideation or cognitive fragmentation. Excessive violence typically appears incoherent in pattern but extreme in intensity, with homicides tending to be chaotic and impulsive while maintaining extraordinary levels of brutality. The documented literature links this form of overkill to internal psychological chaos rather than coherent anger or intention [

12].

Culturally motivated overkill includes honor murders or ritualistic murders that demonstrate dominance, punishment, or purification as means to restore order or dignity. In these cases, overkill reflects collective beliefs rather than personal rage, with violence serving symbolic functions within specific cultural contexts.

These typological distinctions provide forensic practitioners with frameworks for analyzing behavioral evidence, understanding perpetrator psychology, and developing investigative strategies. However, these categories are not mutually exclusive, and overkill may co-occur with other forms of extreme violence, making clear classification challenging in complex cases [

9].

Ultimately, it must be highlighted that some studies posit that overkill functions as a deliberate forensic countermeasure, strategically intended to compromise evidence and impede authorities from successfully identifying the perpetrator [

13,

14].

Table 1.

Typological Framework of Overkill in Homicidal Contexts [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14].

Table 1.

Typological Framework of Overkill in Homicidal Contexts [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14].

| Overkill Type | Primary Motivation | Perpetrator Characteristics | Victim Relationship | Crime Scene Features | Violence Pattern | Post-Crime Behavior |

|---|

| Expressive | Intense emotional arousal | Emotional dysregulation; intimate relationship conflicts | Intimate partners, family members, close friends | Domestic settings; improvised weapons; lack of premeditation | Impulsive, unplanned; injuries to face, neck, chest; symbolic violence | Spontaneous confession; remaining at scene; remorse; potential suicide attempts |

| Instrumental | Specific goals (robbery, financial gain, revenge) | Criminal/psychopathic traits; calculated approach; no emotional ties to victim | Typically strangers or acquaintances | More organized; premeditated elements | Excessive violence as unintended escalation rather than primary objective | Attempts at concealment; flight from scene |

| Psychotic | Delusional ideation; cognitive fragmentation | Severe mental illness; disorganized thinking patterns | Variable; often random selection | Chaotic, disorganized; extreme brutality | Incoherent pattern but extreme intensity; linked to internal psychological chaos | Erratic behavior; possible catatonia or continued disorganization |

| Culturally Motivated | Honor restoration, ritualistic purposes, dominance demonstration | Adherence to cultural/religious belief systems | Determined by cultural context (family honor, social transgressions) | Ritualistic elements; symbolic arrangements | Violence serves symbolic functions; may follow prescribed patterns | Behavior consistent with cultural expectations; possible pride in act |

| Sexual | Sadistic arousal, paraphilia gratification, fantasy fulfillment | Organized or disorganized patterns; may involve necrophilic behaviors | Often strangers; victim selection based on vulnerability or fantasy | Erogenous zone targeting; ritualistic elements; possible dismemberment | Excessive violence serves arousal and symbolic purposes | Evidence destruction attempts; body positioning; trophy taking |

Regarding the types of wounds inflicted on victims, significant efforts have been made to comprehensively assess injuries, particularly in such cases. The utility of quantitative analysis of homicidal injuries lies in its capacity to summarize patterns of offender behavior (e.g., in sexual offenses) [

15], thereby aiding police investigations. Furthermore, such analysis can elucidate the nature of a violent crime and the dynamics of the offender-victim interaction. This dynamic is anecdotally recognized within the law enforcement community, where the extent and anatomical location of injuries often suggest a pre-existing relationship between the perpetrator and victim [

16,

17,

18].

For forensic studies, the Homicide Injury Scale (HIS) was developed to capture overkill features or excessive injuries in victims [

15]. For this purpose, overkill features, based on multiple examples provided by Unsinger [

14], are classified as an HIS score of 5 or 6, as shown in

Table 2 [

15].

The HIS aims to provide a standardized quantitative measure of injury severity. While delineating the nature of injuries can be more useful in differentiating offender variables, the need for greater specificity and accuracy in victim injury analysis led to the development of the HIS for measuring homicidal injuries. This measure allows for the comparison of injuries across large samples of cases that may involve diverse causes of death and varying levels of injury. The HIS seeks to quantitatively capture the qualitative element of a victim’s fatal injuries within the context of homicide. This is achieved by quantifying the severity of only those injuries directly related to the cause(s) of death, based on a detailed review of the medical examiner’s autopsy report and related protocols. The HIS was thus formulated to document the number of causes of death and associated injury severity as identified by a medical examiner.

This study applies these principles to a case that represents one of the earliest documented instances of overkill in the history of forensic medicine and criminology. The primary objective is to examine a case subject to a formal, albeit rudimentary, medico-legal analysis. This case makes it distinct from other historical examples of overkill (e.g., Julius Caesar was assassinated with 23 stab wounds, according to Suetonius [

19]), which were not formally investigated from a medico-legal perspective that approximates contemporary standards.

Specifically, we examined the murder of Mary Jane Kelly, the final victim of the infamous Jack the Ripper, a case that, alongside those of the Zodiac Killer and the Monster of Florence, stands as one of history’s most renowned examples of an unidentified serial killer.

Between 31 August and 9 November 1888, the Whitechapel district of London’s East End was the scene of five murders, collectively attributed to an unknown murderer, popularly called Jack the Ripper. The victims were all women involved in sex work. Forensic analysis of the five cases reveals a consistent and chilling pattern of violence (

Table 3). All but one victim were strangled and had their throats cut. Following death, four of the five victims were extensively mutilated; the single exception was likely spared post-mortem desecration due to the perpetrator being interrupted before completing the act. These events consistently occurred late in the evening or during the early morning hours, with the final victim being killed indoors [

20]. We specifically focused on this final murder, emphasizing the unprecedented brutality inflicted upon the victim’s body. Indeed, Jack the Ripper’s final victim is considered to be Mary Jane Kelly, whose severely mutilated body was discovered on 9 November 1888 [

21].

This case can be considered as an early example of overkill. However, it is recognized that the sources pertaining to the Jack the Ripper case are incomplete when judged by contemporary standards, rendering the application of modern procedures difficult and challenging.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive retrospective analysis combining systematic literature review with standardized forensic assessment protocols was employed. The methodology encompassed multiple phases designed to ensure scientific rigor while acknowledging the inherent limitations of historical case analysis.

A review of currently published studies was performed following the PRISMA criteria [

23]. The completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided as

Supplementary Materials. The literature review phase involved systematic searches of peer-reviewed scientific articles published in forensic medicine and criminology journals, establishing the foundational understanding of overkill concepts and classification systems. Primary databases including PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were systematically searched using the search terms (((overkill) AND (forensic pathology)) OR (overkill)) AND (criminology).

Only the documents published between 1950 and 2025 were included. The timeframe 1950–2025 was selected as it corresponds to the modern era of forensic pathology following the establishment of standardized medicolegal investigation protocols. The initial electronic data search yielded a total of 43 potentially relevant studies on PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus. The articles were carefully evaluated based on their titles, abstracts, and texts. The implementation of these procedures resulted in only 20 eligible papers for inclusion from the initial 43 articles within the search (

Figure 1).

To broaden the analytical scope and provide comprehensive historical context, we extended our research beyond peer-reviewed literature to include scholarly monographs, reputable popular science publications dedicated to the Jack the Ripper murders, and archival materials from contemporary sources. This multifaceted approach ensured access to original historical documents, police reports, and contemporary medical accounts that might not be available through traditional academic databases. Online archival repositories and specialized websites such as

https://www.casebook.org (accessed on 31 August 2025) were consulted to access primary source materials relevant to the investigation.

The inclusion of non-peer-reviewed historical sources, while necessary given the historical nature of this case, introduces potential interpretive bias that requires explicit methodological mitigation strategies. To address these limitations, we implemented several protective measures:

Triangulation methodology. All historical claims were cross-referenced across multiple independent sources (contemporary police reports, and medical documentation) to identify consistent factual elements versus interpretive variations;

Primary source prioritization. Whenever possible, we relied on direct transcriptions of original Victorian-era medical and police documents rather than secondary historical interpretations, with explicit notation when relying on interpretive sources;

Conservative interpretation approach. In cases where historical sources provided conflicting accounts or ambiguous details, we adopted the most conservative interpretation and explicitly noted uncertainties rather than making definitive claims;

Systematic exclusion criteria. We excluded sensationalized popular accounts and unverified claims that could not be corroborated through multiple independent sources. These methodological safeguards do not eliminate interpretive bias inherent in historical documentation but provide systematic frameworks for minimizing its impact on analytical conclusions.

In view of this, the analysis primarily relies on interpretations and transcriptions of original Victorian-era documents rather than direct access to primary autopsy records. This creates multiple layers of potential interpretive bias, translation errors, and selective reporting that cannot be fully corrected through retrospective analysis. The absence, or inadequacy, of original photographic documentation, standardized measurement protocols, and systematic evidence collection procedures characteristic of modern forensic practice fundamentally constrains the reliability of behavioral and pathological conclusions that can be drawn from available materials.

Furthermore, the HIS was applied to documented autopsy findings using established criteria developed by Safarik & Jarvis [

15]. Given the limitations of historical documentation, the assessment focused on clearly documented injuries that could be reliably classified according to HIS parameters. The application of the HIS to nineteenth-century autopsy findings represents an innovative but inherently problematic approach. Indeed, the HIS was developed and validated using modern forensic autopsy protocols that include standardized injury measurement techniques, systematic photographic documentation, comprehensive toxicological analysis, and consistent anatomical terminology, none of which were available or standardized in Victorian-era medical practice. Victorian autopsy procedures lacked the quantitative precision required for reliable HIS scoring, with injury descriptions often using subjective terminology (e.g., “extensive”, “severe”) rather than precise measurements, anatomical locations described using non-standardized reference points, and incomplete documentation of injury characteristics necessary for contemporary classification systems. The temporal and cultural gap between modern forensic standards and 1888 medical practice introduces systematic measurement error that cannot be fully quantified or corrected through retrospective analysis.

The systematic literature review was conducted with the primary objective of establishing a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding overkill phenomena in homicidal contexts. This literature review served to contextualize the historical case analysis within contemporary forensic understanding, providing the necessary conceptual foundation to categorize and interpret the observed patterns of extreme violence in the Mary Jane Kelly murder. Specifically, the review aimed to: (1) synthesize current definitions and classification systems of overkill behavior; (2) identify established typological frameworks for categorizing excessive violence in homicide; (3) compile validated assessment tools, particularly the HIS, for quantitative analysis of injury patterns; and (4) establish comparative benchmarks against which the historical case could be evaluated. This comprehensive review of existing literature was essential to position the Kelly case within the broader spectrum of overkill behaviors and to apply contemporary forensic frameworks to historical evidence, thereby bridging the gap between 19th-century documentation and modern forensic understanding.

Source Reliability and Bias Assessment

The historical nature of this case necessitates explicit evaluation of source reliability and potential systematic biases that may compromise analytical validity. Victorian-era medical and police documentation was conducted without modern standardization protocols and was influenced by period-specific cultural, social, and professional biases that must be critically assessed.

Medical documentation from 1888 was conducted by physicians Thomas Bond and George Bagster Phillips, whose training, experience, and methodological approaches differed significantly from contemporary forensic pathology standard. Victorian medical education emphasized clinical observation but lacked systematic crime scene documentation protocols, standardized injury measurement techniques, and photographic evidence collection that characterize modern forensic practice [

24].

Police documentation reflects the investigative priorities and capabilities of the Metropolitan Police Force in 1888, which lacked modern criminal investigation techniques, behavioral analysis frameworks, and systematic evidence preservation protocols [

25]. Contemporary police reports were primarily concerned with immediate investigative needs rather than comprehensive forensic documentation, potentially leading to selective recording and interpretive bias in favor of prevailing criminal theories of the period.

Popular press coverage and subsequent historical accounts have introduced additional layers of interpretive bias, sensationalism, and factual distortion that complicate accurate assessment of original evidence [

26]. The legendary status of the Jack the Ripper case has generated extensive secondary literature that may inadvertently perpetuate inaccuracies or emphasize dramatic elements over medicolegal precision.

These source limitations require that all conclusions drawn from this historical analysis be considered tentative and subject to revision should additional primary documentation become available. The present analysis acknowledges these constraints while attempting to extract scientifically useful insights within the boundaries imposed by historical documentation quality.

3. Results

According to available historical records, Mary Jane Kelly, also known by aliases such as Marie Jeanette Kelly, Mary Ann Kelly, Ginger, and Fair Emma, was the last victim of the five canonical Whitechapel murders. Born in Limerick, Ireland, around 1863, she was approximately 25 years old at the time of her death. Kelly was described as 5′ 7″ tall and stout, with blonde hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. She had migrated through Wales before ultimately settling in the Whitechapel district of London, where she resided in various lodging houses and worked primarily as a prostitute [

27].

The discovery of Mary Jane Kelly’s body occurred on 9 November 1888, at 13 Miller’s Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, marking the canonical conclusion of a series of homicides that transpired during the period known as the “Autumn of Terror”. Her landlord’s assistant, sent to collect overdue rent, peered through a window to find her mutilated remains on her bed. The extensive nature of the dismemberment and evisceration of her body immediately distinguished this crime from the earlier Whitechapel murders, presenting an unprecedented challenge to the rudimentary forensic practices of the era.

The forensic examination was conducted by doctors Thomas Bond and George Bagster Phillips, whose detailed observations provided critical documentation for subsequent analysis [

27]. Doctor Phillips determined that the primary cause of death was exsanguination resulting from the severance of the carotid artery, an injury sustained while the victim was positioned on the right side of the bedstead. This finding is pivotal for understanding the temporal sequence of events, as it indicates that the extensive mutilation documented subsequently occurred entirely post-mortem.

The autopsy revealed a systematic pattern of injury that can be categorized into distinct phases of violence. The fatal injury comprised a circumferential neck laceration that penetrated through the epidermis and deep tissues to reach the vertebral column, with the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae showing deep incisions accompanied by evident ecchymoses in the superficial anterior cuts. This injury completely severed the respiratory tract at the inferior laryngeal level through the cricoid cartilage, resulting in immediate incapacitation and death. The subsequent report describes the documented post-mortem observations based on the authors’ analysis derived from the consulted sources [

22,

28], providing an account of the injuries present on the victim’s body.

The deceased was discovered in a supine position on a bed with an axial deviation toward the left side. The positioning of the extremities suggested no evidence of a defensive struggle: the left upper extremity was adducted against the torso with the forearm flexed at 90° degrees across the abdomen, while the right upper extremity demonstrated slight abduction with elbow flexion and a supinated forearm position. The lower extremities were positioned in an abducted configuration with the left thigh perpendicular to the torso and the right thigh forming an obtuse angle with the pubic region.

Following death, the perpetrator engaged in extensive post-mortem mutilation that demonstrated methodical organization rather than chaotic violence, characterized by complete evisceration with systematic removal of superficial tissues from the abdomen and thighs. Bilateral mammary gland excision was performed through circular incisions while preserving underlying pectoral musculature to the costal framework, with intercostal space incisions between the fourth, fifth, and sixth ribs exposing thoracic cavity contents. Systematic flaying extended to the extremities, with the right thigh completely denuded anteriorly to the bone and the left thigh stripped of skin, fascia, and musculature to the knee level. Distinctive organ placement patterns included the uterus and kidneys with one breast positioned beneath the head, the contralateral breast adjacent to the right foot, the liver situated between the feet, intestinal loops arranged beside the right flank, and the spleen positioned on the left side. Excised skin flaps from the abdomen and thighs were deliberately placed on a nearby table, indicating methodical organization rather than random mutilation.

Crime scene analysis revealed victim’s garments carefully arranged near the fireplace, with no murder weapon recovered despite clear sharp force trauma evidence requiring a large blade. Blood distribution patterns demonstrated bed linen saturation in the left corner, a significant blood pool (approximately 0.18 m2) on the floor beneath the bed, and arterial spatter on the right wall at neck height consistent with carotid artery severance. Facial trauma rendered features completely unrecognizable through systematic mutilation affecting all head and neck anatomical structures, with partial avulsion of the nose, cheeks, eyebrows, and ears, complete loss of lip tissue with multiple oblique incisions extending to the mental region, and numerous irregular lacerations across all facial features.

Thoracic examination revealed sparse pleural adhesions of the right lung with consolidated adhesions suggesting pre-existing respiratory pathology, crushed and torn inferior right lung portion during assault, intact left lung with apical and lateral adhesions, and multiple pulmonary parenchyma consolidation nodules. The pericardium was found to be open with the complete absence of the heart from the thoracic cavity; this organ was never recovered from the crime scene despite extensive investigation. Extremity examination demonstrated extensive irregular bilateral upper extremity lacerations, right thumb superficial incision (2.5 cm) with subcutaneous hemorrhage, dorsal hand abrasions, complete anterior right thigh denudation to the bone including the external genitalia and a right gluteal region portion, and a left calf longitudinal laceration through skin and deep tissues extending from the knee to 13 cm above the ankle.

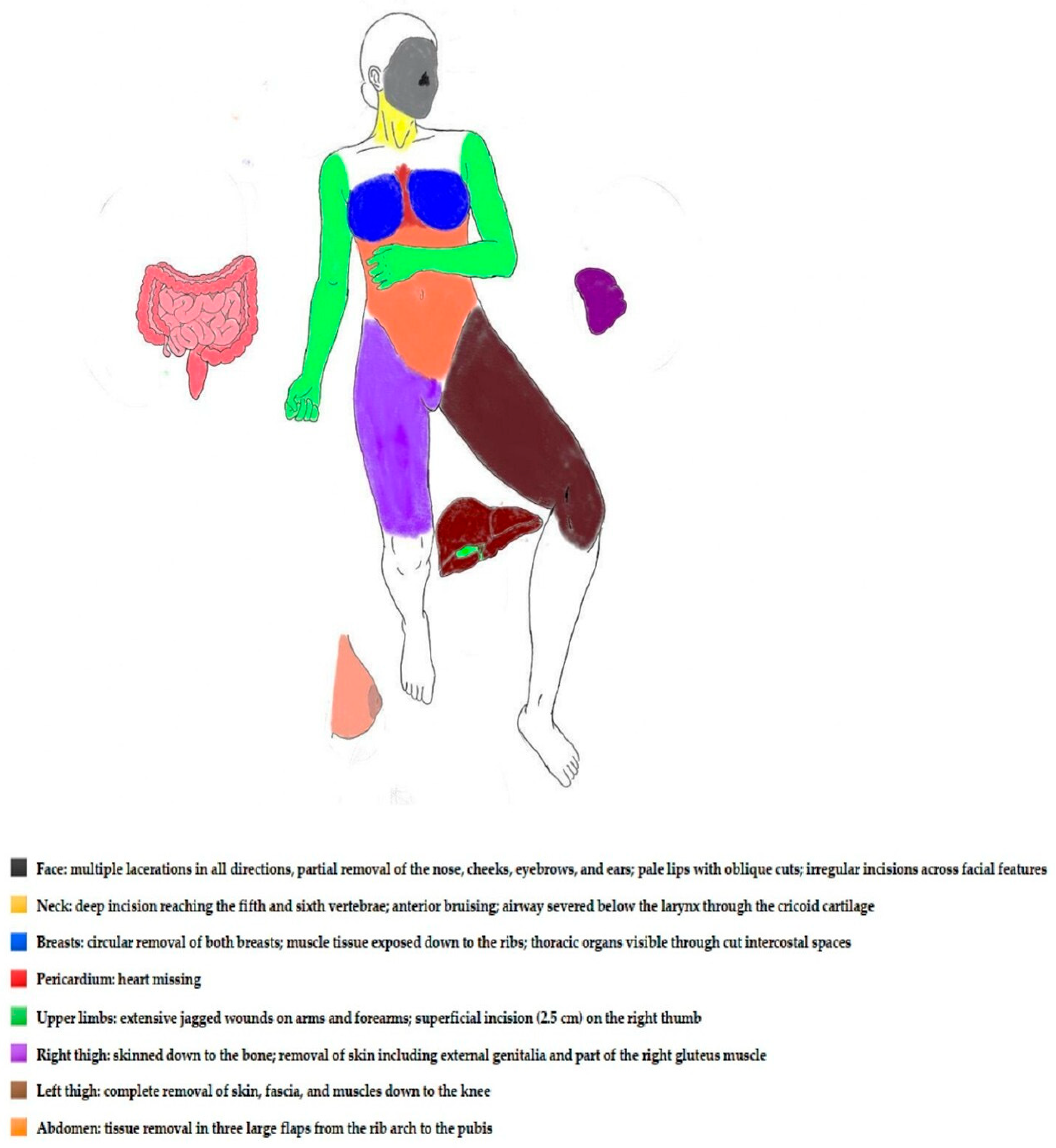

A comprehensive schematic illustration depicting the anatomical distribution and severity of injuries sustained by Mary Jane Kelly is presented in

Figure 2, providing a systematic visual representation of the documented forensic findings.

Application of the HIS yielded a maximum score of 6, based on multiple causes of death comprising primary carotid artery severance and secondary exsanguination from multiple sources, combined with extensive post-mortem mutilation far exceeding lethal requirements. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

Kelly case characteristics should be analyzed within the broader context of sexual homicide overkill patterns. Sexual homicide cases demonstrate significantly higher rates of overkill behavior compared to non-sexual homicides [

6]. This elevated frequency suggests that sexual motivation creates psychological conditions that facilitate extreme violence beyond lethal requirements. However, Kelly’s case presents characteristics that both align with and diverge from established sexual homicide patterns. While Ressler et al. documented that sexual homicide overkill often involves disorganized behavioral patterns [

7], including impulsive attacks and chaotic crime scenes, Kelly’s murder demonstrates organized methodical behavior that contrasts with typical disorganized presentations. This distinction suggests that overkill in sexual homicides may encompass a broader spectrum of behavioral patterns than previously recognized, ranging from impulsive disorganized violence to systematically organized mutilation. Indeed, Kelly’s case demonstrates that overkill in sexual context can also manifest through controlled, systematic approaches. This finding suggests that sexual homicide overkill may encompass a broader behavioral spectrum than previously recognized, with different perpetrator subtypes expressing extreme violence through distinct organizational frameworks.

The extensive mutilation documented in Kelly’s case exceeds all proposed thresholds for overkill classification. According to Tamsen et al.’s criteria [

3], the case demonstrates multiple qualifying factors: significantly more than 40 skin injuries, multiple sharp force wounds to the head, neck, and trunk with internal organ involvement, and systematic evisceration. The methodical nature of the post-mortem mutilation, including the deliberate arrangement of organs and tissue around the crime scene, suggests a level of organization that distinguishes this case from the impulsive violence typically associated with passion-driven overkill scenarios documented in contemporary forensic literature.

The systematic nature of Kelly’s injuries raises important questions about the relationship between crime scene environment and overkill expression. Environmental criminology research demonstrates that physical space significantly influences offender behavior and decision-making processes [

29]. The indoor location of Kelly’s murder provided unprecedented privacy and time compared to the previous outdoor Ripper murders, potentially explaining the dramatic escalation in mutilation complexity. This environmental factor suggests that overkill behavior may be more situationally constrained than previously recognized, with perpetrator capability being limited by external factors rather than psychological boundaries alone.

To provide a comprehensive analysis of the findings, the documented evidence from Kelly’s case has been systematically organized according to anatomical regions and forensic significance.

Table 4 presents a detailed breakdown of the post-mortem findings, demonstrating the systematic nature of the violence and its classification according to contemporary forensic standards.

Kelly’s injury pattern reveals several critical forensic characteristics. Indeed, the absence of defensive wounds and the systematic nature of mutilation clearly indicate post-mortem alterations, establishing a definitive temporal sequence of events. This finding represents a clear distinction from cases where overkill occurs during the fatal assault itself, suggesting different perpetrator motivations and behavioral control mechanisms. The temporal separation between the immediately fatal neck laceration and the extensive subsequent mutilation indicates that the continued violence served symbolic, psychological, or investigative countermeasure purposes rather than ensuring victim death.

The circumferential neck laceration penetrating to the vertebral column would have resulted in immediate incapacitation and rapid exsanguination, rendering all subsequent activities purely post-mortem behavior. This clear temporal demarcation between lethal and post-mortem violence provides important insights into perpetrator psychology and behavioral control, as the extensive mutilation required sustained focus and systematic approach over an extended period. Such behavioral characteristics contrast sharply with impulsive, emotionally driven overkill patterns and suggest premeditation and deliberate planning.

Unlike typical overkill cases that involve known perpetrators driven by interpersonal conflict or emotional rage, Kelly’s murder suggests characteristics consistent with predatory behavior by an unknown perpetrator. The methodical organ removal, systematic tissue arrangement, and evidence of anatomical knowledge suggest a different motivational framework compared to the intimate partner violence scenarios that comprise most contemporary overkill cases.

The comparative analysis framework presented in

Table 5 illustrates these fundamental differences between traditional intimate partner overkill cases and the Kelly murder, highlighting unique characteristics that suggest the need for expanded approaches.

This comparison demonstrates that perpetrator typology and motivational context significantly influence the manifestation of overkill behavior, with implications for both forensic analysis and investigative approaches.

Comparative analysis of the four preceding canonical Ripper victims reveals a consistent pattern of post-mortem mutilation, albeit of significantly lesser complexity compared to the Kelly case. Mary Ann Nichols sustained abdominal cuts extending from ribs to pelvis with two stab wounds to the genitals, representing basic post-mortem mutilation limited by outdoor exposure. Annie Chapman demonstrated more extensive mutilation with systematic organ removal including the uterus, portions of the abdominal wall, upper vagina, and bladder, indicating escalating post-mortem behavior. Elizabeth Stride represents the notable exception, presenting only the fatal throat laceration without subsequent mutilation, likely due to interruption of the perpetrator’s activities. Catherine Eddowes exhibited significant facial mutilation with nose tip and lip removal, extensive abdominal evisceration with intestines drawn over the shoulder, and systematic organ removal including the left kidney and uterus. These patterns establish a baseline of post-mortem mutilation behavior across the series, characterized by progressive anatomical targeting and systematic organ removal, though substantially less comprehensive than the unprecedented systematic dismemberment observed in the Kelly case.

When examining the Kelly murder in relation to the four preceding canonical Ripper victims, comparative analysis reveals that while all five victims demonstrated the characteristic throat laceration, Kelly’s case exhibits an unprecedented escalation in post-mortem mutilation complexity that appears directly related to environmental opportunity rather than fundamental behavioral change. The indoor crime scene location provided extended privacy that facilitated the comprehensive anatomical activities observed, suggesting that environmental constraints significantly influenced the expression of overkill behavior in the earlier outdoor crime scenes.

This environmental influence on overkill expression represents an important consideration. The progression from limited outdoor mutilation time to unrestricted indoor systematic dismemberment suggests that perpetrator capability for extreme violence may be constrained by situational factors rather than psychological limitations. This finding indicates that assessment of overkill potential should consider environmental opportunities alongside perpetrator characteristics when evaluating case risk factors and investigative priorities.

However, the historical nature of this case presents significant methodological limitations that must be explicitly acknowledged. The application of contemporary forensic frameworks to nineteenth-century documentation involves substantial interpretive challenges. Victorian-era autopsy standards differed fundamentally from modern protocols, such as lacking systematic wound measurement and photographic documentation. The available documentation represents interpretations filtered through nineteenth-century medical understanding and investigative priorities, potentially introducing systematic biases that cannot be fully corrected through retrospective analysis. Furthermore, the absence of modern forensic techniques including toxicological analysis, DNA evidence collection, advanced imaging, systematic trace evidence recovery, and technologies based on artificial intelligence (AI) [

30] limits the depth of analysis possible. Contemporary forensic pathology relies heavily on these methods for comprehensive case assessment, and their absence from historical cases creates analytical gaps that must be acknowledged when drawing conclusions about behavioral patterns and perpetrator characteristics.

The systematic removal and placement of specific organs, particularly the missing heart, demonstrates selective targeting that extends beyond random mutilation. However, the significance of these behavioral choices must be interpreted cautiously given the limitations of historical documentation. While the organ arrangement suggests methodical planning and anatomical knowledge, the absence of contemporary crime scene photography and systematic evidence collection protocols limits the certainty with which these behavioral inferences can be drawn.

Kelly’s case challenges traditional overkill conceptualizations by suggesting that extreme violence classification requires both quantitative injury assessment and qualitative behavioral analysis. The systematic organ arrangement and methodical tissue removal indicate that overkill behavior encompasses more than simple injury multiplication, with implications for how forensic practitioners classify and analyze extreme violence.

The application of the HIS to this historical case attempts to provide a framework for quantifying extreme violence, though the fundamental limitations of nineteenth-century documentation prevent reliable scoring according to contemporary standards. While the available evidence appears to be consistent with a score of 6, this assessment remains highly tentative due to incomplete forensic records, lack of standardized injury measurement, and the filtering effects of Victorian-era reporting practices. The confidence intervals for this historical HIS application would be unacceptably wide by modern forensic standards, and conclusions drawn from this scoring must be considered preliminary at best. This analysis exemplifies the inherent tensions between historical case examination and contemporary forensic standards. The three primary methodological concerns raise, source bias mitigation, limitations of retrospective tool application, and empirical grounding of comparative frameworks, represent fundamental epistemological challenges in forensic historiography rather than correctable technical limitations. While we have implemented systematic safeguards to minimize interpretive bias, applied modern assessment tools with explicit acknowledgment of their limitations, and grounded comparative analysis in empirical literature, the fundamental constraint remains that Victorian-era documentation cannot be retroactively transformed into data meeting contemporary forensic standards. Therefore, all conclusions drawn from this historical analysis should be understood as interpretive frameworks for conceptualizing extreme violence patterns rather than definitive forensic determinations. The value of this analysis lies not in providing conclusive answers about a specific historical case, but in demonstrating how modern forensic frameworks can be cautiously applied to historical evidence to generate hypotheses about behavioral patterns that may inform contemporary understanding of overkill phenomena.

Indeed, from a medicolegal perspective, this case illustrates the importance of systematic documentation of injury patterns, organ displacement, and crime scene organization in suspected overkill cases. The methodical nature of the mutilation provides investigative leads regarding perpetrator characteristics that remain relevant to contemporary serial homicide investigations, demonstrating the continued value of historical case analysis for modern practice. Kelly’s case underscores the value of applying injury assessment tools like the HIS to historical cases, as this approach provides quantitative frameworks for comparing violence patterns across different temporal periods and jurisdictions. Such comparative analyses may reveal consistent behavioral patterns that transcend historical and cultural contexts, contributing to our understanding of extreme violence in homicidal behavior.

5. Conclusions

The Mary Jane Kelly murder represents a seminal case in the forensic understanding of overkill behavior, demonstrating extreme violence characteristics that exceed all contemporary classification thresholds. The systematic nature of the post-mortem mutilation distinguishes this case from typical passion-driven overkill scenarios and provides insights into organized predatory behavior patterns. While historical limitations constrain the depth of forensic analysis possible, the case remains valuable for understanding the spectrum of extreme violence in homicide and the application of quantitative injury assessment tools to historical forensic cases. The findings support the continued development of standardized approaches to overkill classification and emphasize the importance of considering both quantitative and qualitative aspects of extreme violence in forensic analysis.

This retrospective analysis examines the Kelly murder as an early overkill case, focusing on forensic characteristics rather than perpetrator identification. By examining the unprecedented ferocity inflicted upon the victim, we seek to illuminate the unique forensic and criminological dimensions of this crime. While it is tempting to speculate on how modern DNA analysis, advanced fingerprinting techniques, sophisticated behavioral profiling, or the application of AI might have altered the course of the original investigation, potentially leading to a resolution, our focus remains on the historical record of the observed patterns of violence, maintaining victim dignity through objective scientific analysis without sensationalism.

What remains certain is that the crimes committed by history’s most infamous serial killer persist as an unsolved enigma. His identity remains concealed within the gas-lit alleys of Victorian London, as if he simply materialized from and vanished back into the impenetrable fog of time.