1. Introduction

Missing persons and the phenomenon of ‘going missing’ is an understudied and undertheorized area of research, though it has been a significant social issue across the globe for decades [

1]. What has also been referred to as a “silent mass disaster” in the United States [

2], more than half a million missing persons files were entered into the Department of Justice’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) Missing and Unidentified Persons System in 2023 [

3]. According to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUS), a nationwide repository for missing, unidentified, and unclaimed deceased persons, up to 600,000 people are reported missing in the U.S. annually, or about 1600 a day [

4]. Little research, though steadily increasing (e.g., [

5,

6,

7]), has aimed to parse apart sociocultural, structural, and economic risk factors that impact who go missing. ‘Going missing’, or

missingness, often impacts different groups at varying rates, with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (POC) not only going missing at higher rates than their non-POC counterparts across several geographic and cultural contexts [

6,

7] but also suffering worse case outcomes [

8,

9].

Missingness must be understood as a form of ill health on several levels. The rate at which people, especially BIPOC individuals, are going missing should be understood as a racialized public safety issue and ‘public health’ concern [

10], seeing that individual, social, and community health can be negatively impacted by the constant threat of going missing and distress from experiencing disproportionate episodes of missingness, of themselves or others. Individual health is at risk when someone goes missing due to several threats, including physical threats such as exposure to the elements and corporal danger and predation, or the inability to take medications, properly care for oneself, or make informed decisions. Social and community health is at risk when members of society go missing [

11,

12,

13]. Whether a loved one returns or not, episodes of missingness may disrupt all sorts of communal and familial structures indefinitely. However, due to systemic inequalities, lack of preventative measures, investigative funding, and media coverage, or perhaps a lack of interest, the issue of missingness has largely gone unnoticed by law enforcement and policymakers.

The exact socioeconomic, political, and cultural circumstances that cause certain individuals to enter the forensic record as a missing person has also been undertheorized by forensic anthropologists since missing persons research is typically housed under the scope of criminology, sociology, psychology, and law and policy. Forensic anthropologists’ unique disciplinary training in empirical, biocultural, and theoretically engaged research, as well as direct involvement with missing and unidentified persons cases, may lend to the advancement of missing persons research and should be leveraged to identify why people go missing in the first place. Research has shown that health and vulnerability go beyond biological etiologies and are impacted by the intricate interactions between social, cultural, economic, and political structures [

14,

15]. Notably, the sociopolitical structures and economic systems that marginalized groups live within significantly affect their health and quality of life due to the bodily manifestation, or embodiment, of inequalities [

15]. The multifaceted, or intersectional, nature of identity can work to either alleviate or further exacerbate inequalities by shielding or exposing certain groups to adverse experiences [

16]. These structures that work to cause harm to specific subsets of the population have been identified as mechanisms of structural violence from a theoretical anthropological perspective [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Furthermore, from a theoretical perspective utilizing the concept of “necropolitics”, societal structures and systems are not only a detriment to the health of marginalized groups but by not actively restructuring society to promote equity and overall health and wellbeing, the state permits the silent killing of subsets of the population [

22,

23].

Missingness can be a result of structural violence [

24]; missingness can be conceptualized as an ultimate negative health outcome to which different groups are unequally exposed, during which an individual is either divorced from society or deceased, essentially existing in the form of “bare life”, an unstable, unprotected state of being that renders a person most vulnerable [

25]. Macroscale investigations, or “social autopsies” [

26] which consider social issues in relation to forensic anthropological questions, have recently gained traction within the field of forensic anthropology (e.g., [

27,

28,

29,

30]). Here, we theorize a missingness framework that acknowledges missingness as a unique concept that disproportionately affects certain demographics, unequally negatively impacting BIPOC’s individual and community health. By operationalizing theories of structural violence, necropolitics, the 3-body concept, and intersectionality, we develop a conceptual missingness framework through which an understanding of missingness and targeted preventative, investigative and recovery measures may be improved. Additionally, we draw upon the Mississippi Repository for Missing and Unidentified Persons as a case study to discuss demographic patterns of and potential risk factors for missingness.

2. Missing Persons Research: A Review

Missing persons has been a neglected topic of research for a number of reasons. The disappearance of an individual, by its nature, often renders circumstantial and case information unknown to law enforcement agencies and researchers, as well as the public, likely contributing to a lack of knowledge regarding missing persons. Additionally, limited funding and resources may equally inhibit investigative efforts, recovery attempts, and research endeavors. Because of this, the missing persons crisis has been referred to as a “silent mass disaster” [

2] or the “silent epidemic” [

31]. Much of missing persons research has been conducted within the purview of criminology, psychology, and sociology, often focusing on identification, tracking, and recovery techniques [

32,

33,

34], reporting and media trends [

35,

36,

37], or focus on specific locations (i.e., hospitals) [

29] or demographics within missing persons, such as recovery efforts for older adults with dementia [

37]. Many large-scale investigations into missing persons have either been conducted outside of the United States [

12] or focus on certain demographics such as children or migrants (e.g., [

38,

39,

40]). One comprehensive study into the “social, technological, media, community, and political conditions” that impact missing persons investigations is the Missing Persons Project [

13,

40,

41] which analyzed 998 missing-persons reports from the U.S. spanning 1991–2012 (p. 103, [

13]). Morewitz [

13] found that the reasons for an individual’s disappearance can greatly vary, and the rhetoric surrounding a disappearance can greatly impact investigative efforts. Additionally, law enforcement may consider certain individuals, i.e., children, women, the elderly, mentally or physically impaired, more vulnerable (p. 96). However, as noted by Morewitz [

13], more research focusing on demographic patterns and societal conditions of missing persons, as well as their impact on their community is needed.

In recent years, the overrepresentation of ethnic and racial minorities in missing persons data compared to their relative population composition has begun to be investigated. van Langeraad et al. [

7] probed whether investigative efforts into missing persons cases in the United Kingdom are impacted by racial biases. To do this, the authors tested law enforcement agency’s decision making by presenting officers with hypothetical missing persons cases and recording how they would administer investigative resources. Though they did not find racial biases in resource allocation, van Langeraad et al. did find that officers assign risk level to each case differently depending on the ethnicity of the hypothetical missing person (2024). Mental health and suicidal thoughts were found to not be taken into consideration for Black individuals’ suicide risk and ‘possible alternative explanations’ drawn upon for Black individuals’ risk of harm. Sleigh-Johnson et al. [

6] conducted an exploratory analysis into why ethnic minorities are overrepresented in missing persons cases in the UK by surveying professionals who work on missing persons cases. The authors found that these professionals allude to cultural differences, such as stigma surrounding mental health care and “reluctance to access support” (p. 11), vulnerability of some ethnic minorities, especially related to immigration status, and geographic location as being the reason behind the overrepresentation of minorities. These projects provide critical insight into the perspective of practitioners on the investigative side of missing persons cases, though the exact mechanisms through which individuals go missing is still unclear.

The aforementioned research endeavors have all been incredibly important and have illuminated different aspects of missingness across time and space. Also important, however, would be a unifying theoretical conceptualization of missingness, so an overarching “why” and “how” people go missing can begin to be answered, as well as the subsequent solving of the problem. Below, we theorize the structural underpinnings of missingness.

3. Conceptualizing Missingness

Missingness—the threat of, exposure to, and experience of—is shaped by a plethora of internal and external factors, and every disappearance is a unique occurrence. However, theories of structural violence, necropolitics, and bare life, along with frameworks of the three bodies and intersectionality may aid in conceptualizing missingness whilst simultaneously maintaining an understanding of the circumstantial uniqueness of each missing persons case. Beyond the sometimes corporally violent case outcomes met by missing persons, the uneven exposure to missingness, physically violent or not, faced by BIPOC communities in the United States is a form of violence in and of itself.

The concept of violence can be difficult to define and understand due to the myriad forms it can take and the covert and overt ways it manifests in society. Though violence is commonly understood based on physicality and interpersonal contact, highlighted by its definition as “the use of physical force to injure” [

42], it is a complicated concept. Violence can take many forms, be culturally sanctioned and legitimized, historically defined, used to enforce or create cultural order and identities, or it can be a cultural system itself [

43,

44]. Physical violence does not necessitate interpersonal violence, with the highly removed and unpersonal nature of warfare. By focusing on solely somatic, interpersonal contact that results in injury, other kinds of violence evade research and thus continue to be pervasive in society. A particular kind of violence, “structural violence” continues to persist in society and has extremely deleterious and multidimensional effects on large sects of the population.

John Galtung in “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research”, conceptualized “structural violence” to expand the meaning of violence, encompassing more than concrete instances of somatic trauma and injury, moving to include mental, psychological, and physiological restrictions or experiences that have the potential to preclude the wellbeing of an individual or group as violence (p. 170, [

17]). Through this perspective, violence can be understood as a societal structure that may prevent people from reaching their full potential, which is legitimized by cultural attitudes and can result in direct, personal violence [

17,

45]. Structural violence refers to violence which is perpetuated through sociocultural, political, and socioeconomic structures and restrictions which manifest as detrimental outcomes for individuals or groups that are marginalized in a society. Structural violence is the normalization of societal structures that perpetuate inequalities embedded within social systems; it is violent because it causes poor health outcomes, injury, or even death to humans who are unable to avoid such outcomes due to societal mechanisms [

17,

46,

47]. Structural violence occurs when different groups emerge in society due to differences in one or more facets of identity or status [

17]. Due to biases, one group is given more power than other groups and is thus able to control the allocation of resources, often inequitably, severely depriving one or more subsets of the population of sufficient resources or satisfactory quality of life based on their identity or class. Through this process, “marginalized groups” are created and continuously reinforced.

The theory of structural violence has become a cornerstone of research in several academic fields such as peace studies, sociology, and anthropology. Moreover, it is a key theoretical framework in anthropology, most pertinently in medical anthropology, biological anthropology, bioarchaeology, and forensic anthropology. Each subdiscipline approaches the issue of structural violence from a unique perspective, but the foundational theory remains consistent across all fields of inquiry. Within medical anthropology, structural violence is understood as the systemic exertion of violence caused by steep social inequality, which acts to exploit and oppress those at the bottom of the social order [

20] and can manifest as many societal mechanisms that cause harm. Paul Farmer’s phrase “pathologies of power” refers to the pathological consequences that become manifest in individuals who are subject to structural violence [

19]. This oppression affects the marginalized—often poor, racial, ethnic, or gender minorities, disabled individuals, etc.—causing psychologically and physiologically suffering as a direct consequence of oppression. Here, we argue that paths to missingness can be traced back to the disadvantages initially caused by and subsequently exacerbated by structural violence.

Understanding ill health through socioeconomic terms was initially seen as controversial in biomedicine [

20,

21], but illness as an outcome of both internal processes and external stressors—“a social order characterized by oppression and inequality” (p. S5, [

21])—is now widely accepted in the social sciences and anthropology. This paradigm of conceptualizing the body as internally and externally shaped is largely imparted to Scheper-Hughes and Lock’s concept of “the three bodies” [

48]. The concept of the three bodies considers not only the physical body an individual experiences phenomenologically, or the “body-self”, but also the social body as a symbol of “nature, society and culture”, as well as the body politic, which is subject to “regulation, surveillance, and control” by any given polity (p. 7, [

48]). In this conceptualization, along with the concept of embodiment [

49] the body is no longer an isolated biological being, but it is both object and subject, shaped and given meaning by the social and political world within which it is situated. Within these frameworks, the body is understood to internalize and express external environmental factors [

49]. Because of these developments in understanding how the human body comes to be impacted by biological and cultural factors, bioarchaeology, closely aligned with forensic anthropology, has explored manifestations of structural violence in the skeleton for the past several decades.

A theoretical model for the bioarchaeological study of structural violence operates on the presumption that the unequal distribution of skeletal markers of stress or poor health can give insight into which subsets of a population were systemically oppressed [

47]. The bioarchaeological study of structural violence treats the human skeleton as an artifact that displays biological health and stress through markers left on the skeleton when physiological processes are disrupted [

47,

50,

51]. Studies of structural violence in bioarchaeology have manifested on several theoretical levels, from paleopathological investigations into marginalization [

52], to how the acquirement of skeletal material for bioarchaeological academics in the early 19th century was in and of itself an enactment of structural violence due to the “disembodiment” of disenfranchised individuals [

53]. Importantly, due to the great influence of bioarchaeology on forensic anthropology and the significant overlap between the two disciplines and their practitioners, forensic anthropology has begun to employ the theory of structural violence.

Forensic anthropology has often been touted as an atheoretical field due to the idea that the unique nature of each forensic case negates the need for explicit explanatory theories [

54]. Though several practitioners have argued for evolutionary theory as the basis on which human variation and the construction of the biological profile are grounded, others have pointed out that few practitioners actively and explicitly engage with evolutionary theory in their work [

55]. However, efforts have been made to hone forensic anthropology’s engagement with social theory [

28,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Forensic anthropology continues to grow as a theoretically engaged and truly interdisciplinary field. Structural vulnerability is a new perspective borne out of structural violence through forensic anthropology’s goals of becoming more theoretically grounded [

28]. Structural violence and structural vulnerability—an explanatory model of social marginalization based on skeletal markers—reject biological determinism and integrate a biocultural approach to understanding forensic cases seeing that individuals who meet the ultimate negative health outcome—premature, wrongful, or suspicious death or circumstances—and end up in forensic contexts are most often marginalized in life. Though the present work does not incorporate osteological analysis, current theoretical and research ventures in forensic anthropology must be considered to situate this work within the larger context of forensic anthropology because missingness is but one issue that forensic anthropologists work to understand and address.

Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois [

48] call for discretion to be used when using a structural violence theoretical framework, emphasizing that work in this area must be deeply contextualized and informed by an interdisciplinary approach. As Klaus [

47] wrote, the theory of structural violence can only manifest in hierarchical societies. From its inception during the colonial period, the United States has existed as a hierarchical society. In the earliest iterations of American society, the enslavement of Black and Indigenous people was not only legal but encouraged and imperative to the growth of the nation; women and previously enslaved people had no civil, property, or voting rights, and the only people considered human in the eyes of the law and society were white men who owned property [

60]. Because the current work is situated within the United States, a structural violence theoretical framework has been deemed appropriate in the context of missing persons. Important to note is that there are hierarchies analogous to those of the United States’ globally that may result in socioeconomic, political, and cultural marginalization and oppression of subgroups, which may also lead to missingness. Therefore, the present conceptualization of missingness may inform global structures to understand and prevent missingness.

Though such racial hierarchies were produced several centuries ago, they have been continuously reproduced and reified, morphing from explicit societal rules and regulations to engrained dispositions towards “others” and naturalized conceptualizations of adverse health outcomes and comparatively poor living conditions and opportunities for certain demographics. The creation of “others” versus “us,” i.e., Black vs. White, led to biological determinism, with the adverse conditions faced by certain demographic groups being blamed on their mental, physical, or cultural characteristics [

61] rather than outside structures. Through these processes, structural barriers are erected between social groups, and those who are “deserving” of resources and those who are not are defined. Through necropolitics, we can begin to understand the mechanisms through which those who are deemed not deserving of resources are not only treated poorly but eliminated through systemic measures.

Informed by Foucault’s “biopower,” Achille Mbembe drew upon black political thought and political theory to conceptualize necropolitics in response to unsatisfactory attempts to explain how postcolonial states exercise sovereignty upon its citizens. Foucault’s “biopower” refers to the power the state has over the biological dimensions of life [

62]. Biopower considers how political powers in a sovereign state regulate and control the biological aspect of their population, beginning with the statistical quantification of birth rates, mortality rates, etc., in the late eighteenth century (pp. 241–245, [

62]). According to Foucault, sovereignty is the state’s management of the population. Philosophically, because the state cannot “grant life”, sovereignty is the state’s ability to “take life or let live” (p. 241, [

62]). Mbembe expands upon this by proposing necropolitics to explore the specifics by which the state enacts “the right to kill”, a reconceptualization of the passive notion of sovereignty presented by Foucault (i.e., take life, let live). According to Mbembe, with the post-colonial world come new forms of subjugation [

23]. Politics is the work of death, the way by which those who can live and die are defined and subjectified (pp. 12–16, [

23]). Within the contemporary world, subsets of populations are deemed unworthy of life, predicated upon their racial or ethnic identity or economic status, are subjected to living in a state of bare life—or status of living dead—deprived of political status and purposefully and utterly destroyed by the state [

22,

23,

25]. When discussing this Mbembe was referring to death camps, apartheid, and plantation life, but necropolitics was used as an analytical tool in this research for understanding the unequal risk of going missing faced by some groups.

We argue that what is understood to be the ultimate negative health outcome, death, needs to be further radicalized; just as dying, going missing can be seen as an ultimate negative health outcome as it leaves an individual in a state of bare life both physically and socially. As described in Iturriaga and Denman [

63] (p. 5), “passive” violence, such as neglect, that may result in one’s disappearance is no less violent than active embodiments of violence such as murder; these violent acts exist on a spectrum of kind not degree of violence. Within this framework, the individual who goes missing, perhaps indefinitely, suffers from their physicality and their identity being in an indefinite, unknown, and possibly precarious state. Necropolitics is a framework through which we can understand structural violence without having physical remains; the incorporation of necropolitics within forensic anthropology has also been recognized as a manner through which forensic practitioners may advocate for the living and the dead [

64]. Without the return of the missing, those left behind are faced with a specific kind of torture, specifically of the unknown. Societal structures unequally expose certain groups to the risk of going missing as well as suffering from voids left in their community, and by not actively preventing such inequalities, the state is defining who is worthy of resources, investigative efforts, and recovery, and who is not. By not seriously considering and investigating missingness, the State is allowing certain groups to continue being susceptible to going missing or forcing them to disappear, to be subject to bare life, and, in Mbembe’s framework, vulnerable to eventual death.

4. Risk Factors of Missingness

Thus, missingness is one possible end result of structural violence in which structural violence and necropolitics coalesce, leading to a state of bare life, an experience disproportionately faced by marginalized groups, which may result in their death. Within these societal structures, more covert mechanisms of structural violence, which may be expressed as internal and external risk factors, further exacerbate the risk of missingness for certain individuals or groups. In forensic anthropology, missing persons are typically discussed in the context of solving long-term missing persons cases through the profiling of unidentified skeletons [

65,

66], disasters, natural or otherwise, migrants, or cases of mass violence [

67,

68], but here we refer to the collective, yet individual, “everyday” missing person case. While classical forensic anthropological training does allow practitioners to aid in the identification of individuals who have become skeletonized [

69], theoretical anthropological training also gives practitioners the ability to potentially identify patterns of missingness. Those who go missing may disappear through a number of different avenues, be it involuntarily due to cognitive impairment, which may result in disorientation, mental disabilities, a violent scenario in which a third party is responsible for the disappearance of another (e.g., kidnapping, murder), accidents, injury, or voluntary disappearance [

70]. No matter the scenario or route through which someone disappears and is then reported missing, ethnic and racial minorities are overrepresented in almost every instance. Identifying patterns and structural and systemic causes of missingness, though, may aid in the eventual resolution of the threat missingness poses to public health and safety by identifying which measures and community resources may be most effective at preventing missingness. Additionally, preventing people from going missing may also offset subsequent investigative costs, allowing for a redistribution of funds to community resources.

Differential resource distribution is a mechanism of structural violence [

17] and may be a large factor in who is exposed to missingness and who is not. Access to healthcare and mental health services, local law enforcement agencies’ budgets, access to quality food, availability of social services, and more may all impact whether or not an individual winds up in a situation that exposes them to missingness. van Langeraad [

7] and Sleigh-Johnson [

6] found that in the UK, ethnic minorities face systemic disparities in mental health access and treatment, with ethnic minorities suffering more severe mental health problems due to a variety of compounding reasons (p. 11, [

6]; [

71]). Given that mental health is often cited as a factor in an individual’s disappearance, this is but one example of how disparities in resource allocation may be contributing to minority overrepresentation in missing persons cases.

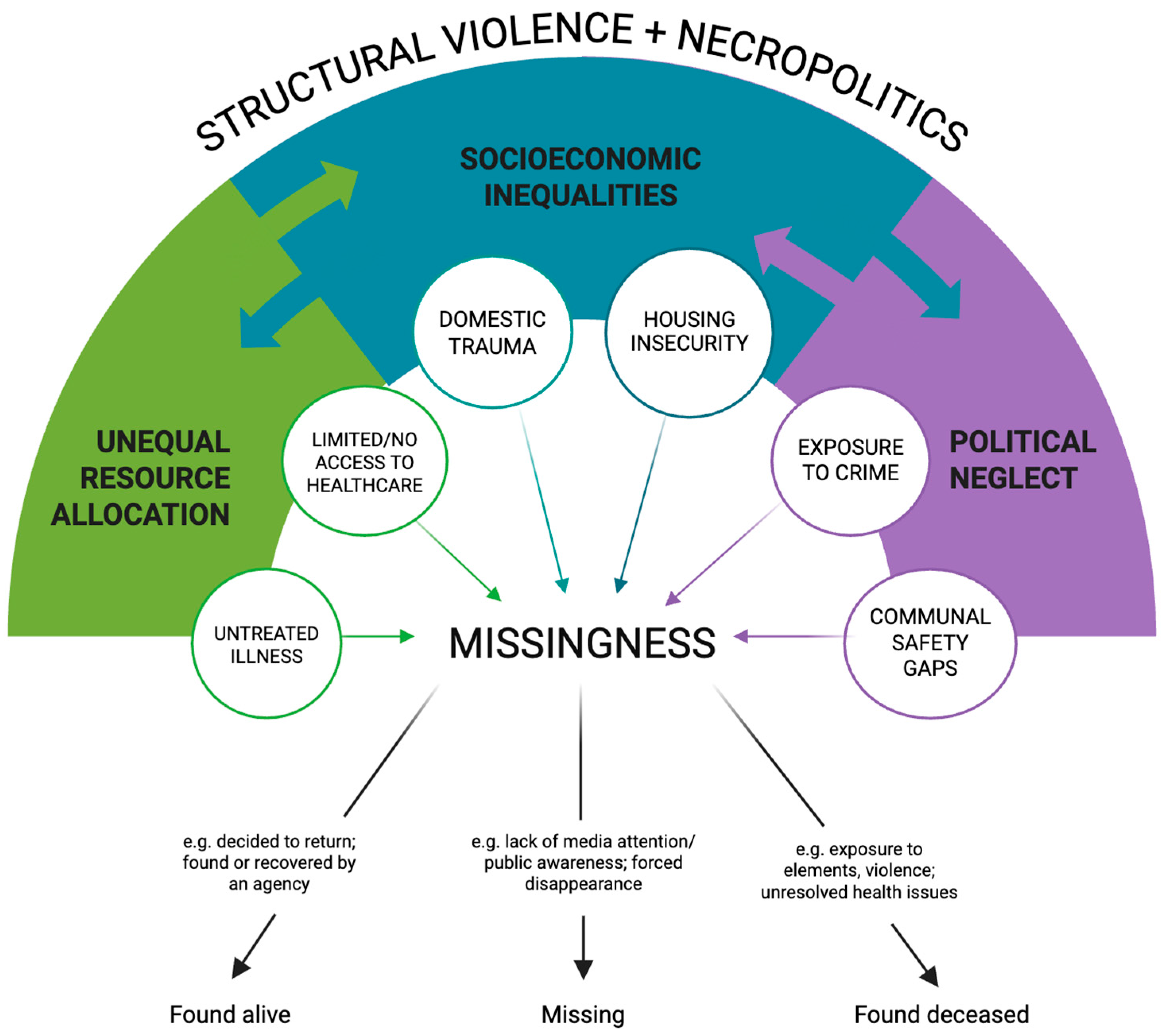

A brief overview of the reported circumstances through which individuals go missing in Mississippi [

8] confirms that many reported individuals disappear when certain social systems fail. Direct violence (e.g., forced disappearances, kidnapping), direct structural violence (e.g., untreated illness, mental or otherwise, due to lack of healthcare; housing insecurity), and communal safety gaps (e.g., missing children, Alzheimer’s wandering) are all examples of how people have gone missing in Mississippi. Additionally, due to systemic and community conditions, certain groups are more likely to live lifestyles that may expose them to dangerous situations or crime-ridden areas [

13,

29]. As demonstrated in the schema below, none of these concepts exist in isolation. These dimensions of missingness are intertwined; all are systemic issues which fall under the umbrella of structural violence and necropolitics and are more likely to affect already-marginalized groups. Below, we present a schema of missingness, utilizing examples from the MS Repository [

8] to demonstrate particular paths to missingness and case outcomes that result from engrained structural violence and necropolitics.

An individual’s identity may also impact whether they are granted access to certain resources. Intersectionality is a lens that reveals how people, specifically women of color, are subjected to several overlapping forms of discrimination or inequality due to the interlocking facts of their identity, both internally and externally assigned. One’s identity can either aggravate or filter risks threatened upon their person. Because of this, research into racialized experiences and inequality within societal structures must utilize an intersectional lens to avoid being one-dimensional, because the human experience is shaped by one’s multifaceted, inextricable identity. Analyzing missingness through utilizing a lens of intersectionality allows for a more thorough and holistic understanding of demographic patterns of missingness. Below, we present a case study utilizing data from the Mississippi Repository for Missing and Unidentified Persons (MS Repository) to discuss demographic patterns of missing persons and case outcomes in Mississippi, understood through the formally developed concept of missingness.

Case Study: The Mississippi Repository for Missing and Unidentified Persons

The MS Repository is a multi-agency collaboration which serves as a statewide database for missing persons reports [

8]. As of June 2025, 2339 missing persons reports have been input into the MS Repository. Of these, 2315 cases were included in the current study due to their completeness of data regarding demographics and case resolution. These missing person cases range from the 1950s to mid-2025 and represent a variety of age cohorts, sexes, and ethnicities/racial groups, and each reported disappearance occurred either within the borders of Mississippi or involved a Mississippian; overall, these missing individuals are united in their connections to Mississippi (

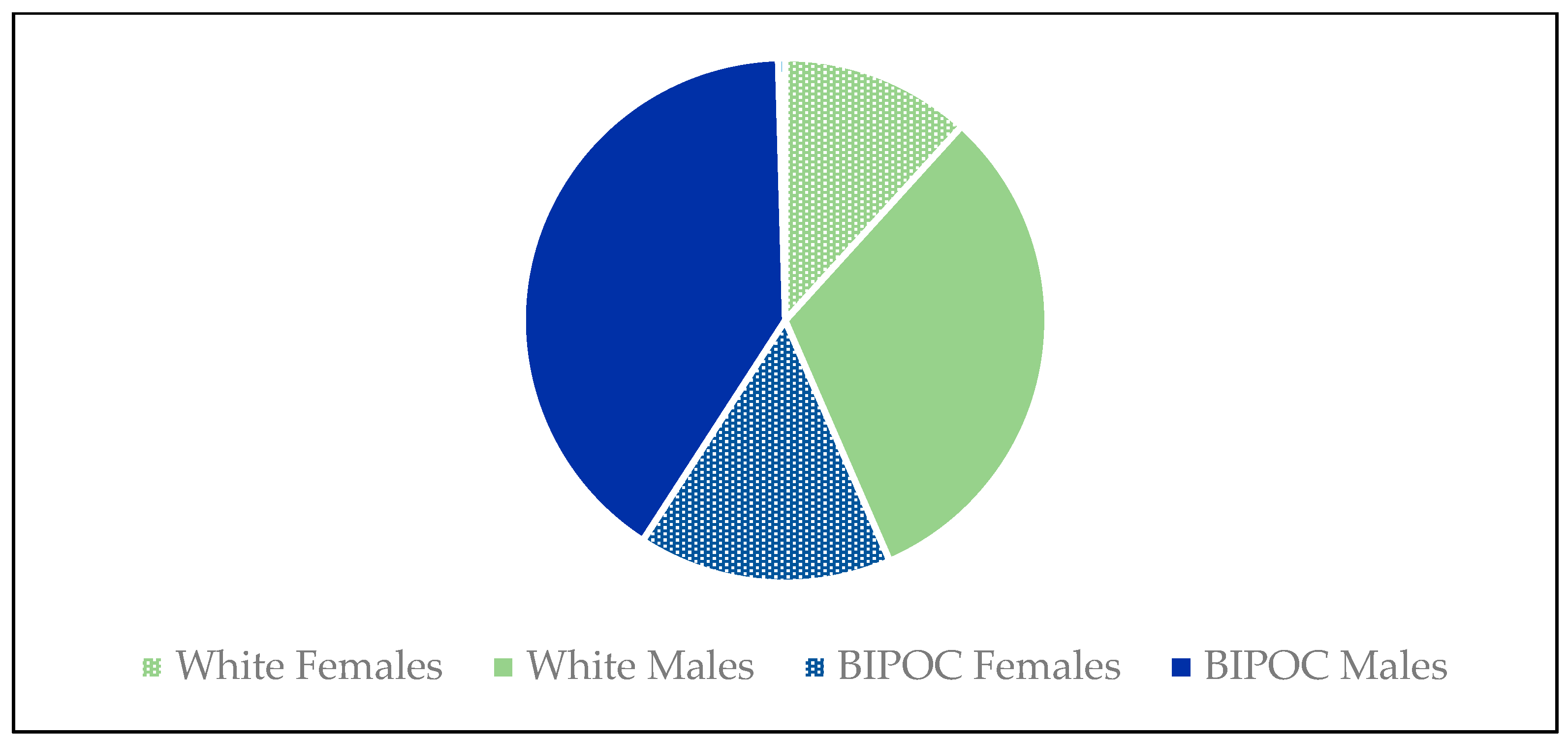

Figure 1).

Descriptive statistics were run on case status, sex, and race/ethnicity to gauge simple demographic distributions. For this study, racial and ethnic categories were collapsed into a “White” and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, “BIPOC” binary due to the small sample size of non-white individuals who are not Black or African American in the MS Repository. Important to note is that these data are a snapshot of reported missing persons in Mississippi. The data are not stagnant or concrete but, rather, oscillating due to the nature of missing persons cases and their ever-changing status, with the possibility of cases being resolved or reopened at any time.

The majority of individuals were recovered alive (50.02%,

n = 1158). 39.65% (

n = 918) remain missing due to their case remaining unsolved (due to a lack of recovery or a lack of case information), and in 10.24% (

n = 230) of the cases, the individual was recovered deceased. BIPOC individuals were overrepresented in the MS Repository compared to the demographic composition of the state. Though BIPOC persons make up about 30% of the population of Mississippi [

72], they comprise 59% of the cases in the MS Repository. Beyond demographic patterns of missingness, differential case outcomes within missingness help paint a picture of the different experiences each demographic face after disappearing. Of those found deceased, 56.5% (

n = 130) were BIPOC; of those found alive, 55.87% (

n = 136) were BIPOC; of the unresolved or open cases (i.e., still missing), 63.62% (

n = 584) are BIPOC. Additionally, though males and females are equally distributed between those who are recovered alive or still missing, of those found deceased, 72.17% (

n = 166) are male; 56.02% (

n = 93) of which are BIPOC (

Figure 2). Sadly, BIPOC individuals who have gone missing and were subsequently found deceased were found to be more likely to die an unnatural or violent death in comparison to their white counterparts.

There is a clear over-representation of BIPOC individuals in the Mississippi Repository for Missing and Unidentified Persons. Understood through the theory of structural violence, there are societal and systemic structures which disproportionately endanger BIPOC individuals to going missing compared to their white counterparts. Throughout the United States, people of color and poorer communities are rendered as dispensable [

73]. Indeed, and unfortunately, missingness in Mississippi is a racialized experience, consistent with—if not exceeding—nationwide trends. The risk of going missing unequally affects marginalized people in Mississippi, which is simultaneously a mechanism and a result of structural violence. The exact mechanisms causing BIPOC people to go missing at inordinate rates throughout the state, are unclear, but the very threat of missingness and the void left when an individual is missing adversely impacts individual and communal health. Utilizing a theoretical perspective of structural violence, as well as an intersectional lens, it can be understood that an individual’s identity and socioeconomic background impact their likelihood of going missing and, unfortunately, impacts their case outcomes as missing persons. As Mbembe wrote, race and classism underpin Western political thought and practice (p. 17, [

23]). The threats experienced by white and BIPOC individuals, within and across gender lines, differ from one another, resulting in differential exposures to missingness as well as differential case outcomes, with BIPOC men suffering the worst-case outcomes in cases reported to the MS Repository.

This may be thought of as a side effect, or, as Mbembe would likely argue, a purposeful outcome, of the deeply entrenched racial and class systems in Mississippi, which result in poor health outcomes, lower educational attainments, and now missingness for marginalized racial and ethnic groups. Due to the variable circumstances surrounding individual disappearances, blanket causative factors may not be deducible. An intersectional lens is integral to understanding why certain individuals seem to be predisposed to going missing and subsequent case outcomes. Though BIPOC men do comprise the majority of individuals who are found deceased after being reported missing, a variety of socioeconomic statuses, occupations, ages, social backgrounds, and life circumstances are represented within this group. Some of these disappearances are related to dementia and mental health issues, others are related to substance abuse or gang activity, while the circumstances of yet other cases seem unrelated to any of these possibilities and their situations remain unclear. Future research would benefit from a detailed analysis of case circumstances to identify trends that may relate to social, political, economic, or cultural structures.

Though BIPOC individuals are overrepresented in the MS Repository, it is important to note that several factors, such as the concept of “missing white woman syndrome”, distrust in law enforcement agencies, and access to technology may contribute to an additional lack of data [

74]. After conducting an empirical analysis to determine whether missing white women actually receive more media coverage than women of color (WOC) and men, Sommers [

74] concluded that missing BIPOC individuals, and WOC especially, receive less media coverage overall, and when they are covered, it is with much less intensity or airtime. Here, it is once again important to consider intersectionality and social perceptions of people within and across gender lines. Because white women are conceptualized as “damsels in distress”, they benefit from greater coverage and subsequent awareness and potential recovery efforts, leaving other cases under-covered and under-investigated. This is not to say that cases of missing white women should be less covered, but rather an equitable distribution of media coverage may result in more holistic data tabulation and potentially case outcomes for all.

Reporting an individual missing can be a complicated process due to several factors. Missing persons often go unreported by family, community members, or law enforcement agencies due to the belief that the case will resolve itself [

75], additionally, BIPOC groups tend to distrust in law enforcement agencies due to histories of police brutality and medical malpractice [

76], which can discourage members of BIPOC communities from contacting law enforcement agencies to report someone missing. Finally, a vast majority of the missing persons reports entered into the MS Repository come from law enforcement agencies’ social media posts. The vetting and filtering process of social media posts by law enforcement may lead to additional gaps in data through several possible routes, including individual biases in “who” deserves to be posted or reposted, case sensitivity, and the case being reported in the first place. With social media being a main route through which missing persons are reported and reports disseminated, law enforcement agencies assume that those affected by missingness have access to social media, which they may not have due to systemic poverty throughout the state of Mississippi. All of these factors may be coalescing to further skew the data, obscuring just how significant disparities within missingness may be.

Though each of these cases is unique, they are all connected by their shared experience of missingness and connection to Mississippi. Mississippi is one of the poorest states in the country, riddled with a history of white supremacy [

77], one of the highest wealth gaps in the country [

78], and health and educational disparities across racial and ethnic lines [

79,

80]. Unfortunately, Mississippi is an exemplary case of how systemic inequities may impact a population, severely disadvantaging certain groups on several dimensions, which may eventually expose them to unprecedented levels of missingness. Though Mississippi is a unique state, especially due to its rural characterization which may pose different threats to its population compared to more urbanized states, the concept of missingness and how it impacts communities different across demographic lines can be applied elsewhere.