Abstract

Background: Sexual violence poses a significant challenge to European lawmakers, impacting the victim’s physical and psychological health. This study examines sexual violence legislation across EU member states, Switzerland, and the UK, analyzing similarities, differences, challenges, and potential solutions for effective policy development. The research was motivated by the adoption of EU Directive 2024/1385. Methods: This study analyzes sexual violence legislation across European countries in a comparative and qualitative way, highlighting differences, commonalities, and the potential for uniform regulation. The data were collected from the literature published between 2015 and 2024, focusing the EU member states, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Results: The examination of the norms governing sexual offenses in various European countries revealed significant differences in legislative frameworks, reflecting diverse cultural, ethical, and legal perspectives. Conclusions: Despite European countries sharing the goal of protecting victims and combating sexual violence, there are significant legislative disparities. Key recommendations include enhancing EU member state cooperation, implementing joint training programs, developing a specific EU directive, and creating coordinated prevention and education programs. While respecting national legal diversity, a unified approach is needed for effective prevention and prosecution of sexual violence across Europe.

Keywords:

sexual violence; forensic medicine; Europe; bioethics; revenge porn; stalking; negligent rape 1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes violence as the deliberate use of physical force or power against oneself (intrapersonal), another individual (interpersonal), or a group or community (collective), leading to or resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, developmental problems, or deprivation. Interpersonal violence ranks as the 19th cause of morbidity and mortality, highlighting its significance as a global health concern. Types of violence include sexual, psychological, and physical [1].

Sexual violence (SV) represents a significant challenge for European institutional bodies. This form of violence has a profound and devastating impact on the victims’ psychological and physical well-being, necessitating standardized political actions at the European level to address this distressing phenomenon and mitigate the increase in victims. SV is any attempted or completed non-consensual sexual experience, including rape, sexual assault, sexual coercion, sexual aggression, and sexual harassment [2].

There are several factors that explain why SV is so deeply rooted in European society. The first point concerns the culture of power and control [3,4]. SV often reflects a situation of power and control by the perpetrator. Indeed, the aggressor exercises dominance over the victim through forced sexual acts. The perpetrator uses the victim as if they were an “object” to be possessed. The second point concerns cultural norms and gender stereotypes. Typically, women are considered more empathetic and sensitive, while men are seen as stronger and more suited to leadership roles. These distorted ideas about masculinity and femininity can contribute to perpetuating rape culture. The third point addresses the lack of sexual education in schools and family environments. In some European countries, sexual education is still considered a taboo topic. Consequently, adolescents with questions on this subject do not know whom to turn to for answers regarding sexual education. The lack of sexual education may undermine respect for others’ bodily autonomy and the notion of consent. Moreover, it is often observed that patients, both young and old, experience significant difficulties when attempting to discuss their sexual issues with their general practitioners. This reluctance to communicate can stem from a variety of factors, including discomfort, embarrassment, or a perceived lack of understanding or support from healthcare providers [5]. Additionally, the rise in dating applications and online meetings has profoundly transformed human interaction. This shift has resulted in increased feelings of loneliness, alienation, and impersonal rejection. Historically, most couples met in physical settings such as universities, neighborhoods, or workplaces. However, today, face-to-face interactions have significantly decreased, with much of human contact occurring in the virtual realm. This transition from physical to virtual interactions has introduced a unique set of challenges. Violence, once confined to physical spaces, now finds a place within digital environments, often erupting when it crosses back into the real world. This type of violence is particularly difficult to combat due to its occurrence in non-physical, virtual spaces, where traditional methods of addressing violence may be less effective. This phenomenon has been extensively discussed in the literature, particularly in the context of virtual-reality application and incidents like the “rape of avatars” [6,7,8,9].

Particular attention must also be paid to the phenomenon of migration. Research shows that compared to the general population, refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants are at greater risk: up to 28.6% of male and 69.3% of female migrants have been subject to SV since their arrival in Europe [10]. The analysis of migratory flows in Europe indicates that migrants, particularly women, are vulnerable to SV during their journey, in detention centers, and even after reaching their destination. The precarious legal status of many migrants often exacerbates their vulnerability, as they may fear reporting incidents due to possible consequences related to the enforcement of immigration laws [11]. In fact, SV against migrants is not limited to physical acts but also includes psychological and coercive abuse. The Mediterranean region has recorded significant episodes of SV among refugees and migrants. This violence is often linked to the lack of legal protection and support systems for migrants, making them easy targets for exploitation and abuse [12]. Indeed, people in insecure migration status are particularly vulnerable to violence, for several reasons. These include lacking recourse to report violence, unregulated transit, lack of accountability for violence against people who are outside of their state jurisdiction, hostile immigration policies, complex immigration policies that make status and associated rights unclear, and a lack of knowledge about administrative structures in host countries [11]. The scarcity of research of the phenomenon of SV among the migrant population in Europe suggests the need for more comprehensive studies to inform prevention and response strategies. Addressing this issue requires an approach that includes legal reforms, improved support services, and greater awareness and education on migrants’ rights [13]. Furthermore, migrant women are particularly exposed to SV not only during their journey but also in destination countries, often in contexts of precarious work or exploitation. The vulnerability of migrant women is accentuated by the lack of support networks and the fear of retaliation or deportation if they report abuse, highlighting the need for more effective policies to protect and support them [14].

Moreover, Europe must address the challenges posed by stalking and revenge porn (RP), which further complicate SV legislation. The legal definition of stalking has taken several different forms, but it typically identifies stalking as an intentional pattern of repeated behaviors toward a person or persons that are unwanted, and result in fear, or that a reasonable person (or jury) would view as fearful or threatening [15].

RP occurs when intimate or sexually explicit images, previously shared with consent, are leaked to a wider audience without the individual’s consent, often by an ex-lover following a relationship breakdown [16].

Another aspect to consider is the introduction of “negligent rape” (NR) by some European states. NR, as defined by various European legislations, refers to situations where an individual engages in sexual activity without taking reasonable steps to ensure that the other party consents. This concept is particularly relevant in countries like Sweden, where the law requires that consent must be voluntary and explicit [17]. In Denmark, the debate around NR centers on the idea that a person should be held accountable if they fail to obtain clear consent, even if they believe the act was consensual [18]. The legal frameworks across Europe vary, but the common thread is the emphasis on the necessity of affirmative consent. For instance, in Sweden, the law stipulates that any sexual act must be based on mutual and voluntary agreement, and failure to ensure this can lead to charges of NR [17]. These legislative approaches aim to protect individuals’ sexual autonomy and ensure that consent is a clear and necessary component of any sexual interaction. The evolving nature of these laws reflects a broader shift towards recognizing and addressing the complexities of consent and SV in modern society [19].

Moreover, it is pivotal to acknowledge the growing recognition of male sexual abuse. Literature indicates varying prevalence rates, with a tendency toward increase. According to Eurostat, in 2015 more than 6000 men and boys were raped and more than 19 000 were sexually assaulted. What is more, the discrepancy between countries was marked: eight countries registered no cases of male rape at all. Considering that, according to studies, (i) male victims of sexual assault are less likely to report incidents to the police and (ii) they are less likely to seek psychological support owing, among other reasons, to the stereotypes on how men should behave [20].

Considering this growing prevalence, it is vital to investigate the impact of male sexual abuse and how individuals can overcome its negative sequelae. The traumatic impact often manifests in dynamics related to sexuality, interrelationships, powerlessness, and stigmatization. Emotions tied to sexual trauma can lead to conflicts with identity, as well as masculine norms and stereotypes, including aggression, rejection of “feminine” characteristics, stoicism, preoccupation with sex, and the expectation of being an economic provider and protector of the home and family [21].

Studies show that the sense of stigma is stronger when the perpetrator is a mother or a woman, as men are unconsciously more often associated with being perpetrators of sexual abuse. The mistaken belief that women cannot be offenders can discourage recognizing an experience as abusive if it involves a woman or a mother. In a study focusing on men forced to penetrate women, Weare [22] showed that this form of female-to-male sexual abuse often results in anxiety, depressive and/or suicidal thoughts, self-harm behaviors, mistrust, and negative feelings of anger, shame, and isolation. Being subjected to penetration can further worsen the sense of stigma and shame. Feelings of powerlessness and loss of control, commonly reported by many male victims, are often seen because of male gender socialization. These feelings can stem from a man’s recollection of being defenseless and can pervade the emotional and relational aspects of his adult life, making him feel unable to succeed or overcome challenges. Additionally, traumatic memory, sometimes referred to as “flashbacks”, often focuses on fragments of the traumatic event and is frequently unexpected. This can worsen feelings of hurt and loss of control, leading to the defensive use of avoidance strategies. Traumatic memory is a symptom of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, along with persistent stress responses, hyperarousal, dysphoric mood, and circadian rhythm dysregulation, and increases the risk of psychoactive substance use and suicidality. Male victims may also experience great fear when facing contact or aggression from others. Some may defend themselves by adopting a hypermasculine and controlling personality. Following sexual abuse, many also exhibit disturbances in identity construction, socialization, and sexual identity development. Given the discrepancy between sexual abuse, its aftermath, and societal beliefs about what a man “should be”, some authors emphasize the need for male victims to renegotiate masculine norms. This renegotiation in adult victims is considered a first step towards “breaking the victim-offender cycle”. However, it is important to note that while perpetrators of sexual abuse often endured it themselves, few men who have experienced sexual abuse reproduce what they went through. Emotional reassurance, social support from friends and family, and positive disclosure experiences are crucial for the resilience process. The #MeToo movement on Twitter has also proven therapeutic for many victims, providing a space for emotional support, sharing, perspective, community, awareness, and accountability for perpetrators and the general population [21].

Few studies investigate male resilience, particularly in France, where approximately 16.1% of men report having been victims of rape or attempted rape. Nevertheless, male SV is widely underreported. The taboo surrounding male sexual abuse remains strong, and professionals often lack information regarding victim care [23].

This article aims to examine the issue of SV by analyzing and comparing European legislation, with the goal of understanding the similarities, differences, common challenges, and potential solutions to develop effective policies to fight this phenomenon.

On this issue, the European Parliament has already adopted Directive EU 2024/1385 on fighting violence against women and domestic violence, which introduces harmonized measures for defining crimes, protecting victims, and ensuring access to justice [24]. Furthermore, this manuscript explores the legislative consequences of SV, as well as the circumstances in which abuse occurs, with the aim of better understanding, addressing and preventing this global public health problem. Understanding the legislative context is important to combat this crime.

Indeed, the landscape of sexual offense legislation in Europe is undergoing a profound transformation, moving decisively from coercion-based models towards consent-based models. This shift marks a fundamental redefinition of SV, aiming to provide more robust protection for victims. Historically, many legal systems operated under coercion-based frameworks. In these models, the prosecution’s primary task was to demonstrate that the perpetrator had employed physical force, threats, or intimidation to overcome the victim’s resistance. The burden often fell heavily on the victim to furnish visible proof of struggle or non-compliance. This approach is typically fixated on the perpetrator’s actions and the presence of external force, rather than the victim’s personal experience or their explicit lack of agreement. In stark contrast, consent-based models establish the absence of affirmative, explicit, and voluntary consent as the defining characteristic of a sexual offense. This paradigm effectively redirects the focus from the presence of force or resistance to the clear presence or absence of agreement. The foundational principle here is simple: any sexual activity undertaken without clear, freely given consent constitutes a sexual offense. As already said, NR pertains to situations where an individual “engages in sexual activity without taking reasonable steps to ensure that the other party consents”. This concept holds relevance in countries like Sweden, where the law dictates that consent must be voluntary and explicit, and in Denmark, where accountability is stressed if an individual fails to obtain clear consent, even if they believe the act was consensual. These legislative advancements highlight several pivotal aspects of consent-based models. Consent, within this framework, is not merely the absence of a “no”, but rather the active and enthusiastic presence of a “yes”. It must be a clear, unambiguous, and voluntary agreement for a specific sexual act. Crucially, consent given for one act does not automatically extend to another, and it can be revoked at any point, even during sexual activity. Valid consent also presupposes that individuals possess the capacity to comprehend the nature of the act and freely agree to it, unburdened by coercion, incapacitation (such as from intoxication), or the exploitation of vulnerability. While not entirely absolving the prosecution, consent-based models place a greater onus on the perpetrator to ascertain consent, shifting the emphasis from the victim’s need to resist. This is evident in the concept of NR, where a perpetrator’s failure to secure consent can lead to charges. Fundamentally, these models are designed to uphold an individual’s right to sexual autonomy, ensuring that all sexual interactions are genuinely consensual and respectful of personal boundaries. The adoption of consent-based models signifies a considerable stride forward in combating sexual violence. This shift is designed to reduce victim blaming, as it inherently diminishes the tendency to scrutinize a victim’s actions or perceived lack of resistance, a common feature of coercion-based approaches. It also broadens the scope of sexual offenses, making it easier to prosecute acts previously difficult to define under older laws, such as those involving incapacitation or subtle forms of coercion. Furthermore, the emphasis on affirmative consent necessitates greater public education on healthy sexual interactions and respectful boundaries.

Despite these advantages, formidable challenges persist. Effective implementation of consent-based legislation demands clear legal definitions that are easily grasped by both the public and legal professionals. It also requires comprehensive training for law enforcement and the judiciary, equipping police, prosecutors, and judges with the necessary understanding and tools to investigate and adjudicate cases within consent-based frameworks. Finally, and perhaps most challenging, is the need for a broader societal shift to overcome deeply ingrained cultural norms, particularly those related to “power and control” and “gender stereotypes”, which can undermine the very principles of consent.

Ultimately, the movement towards consent-based models in European sexual offense legislation represents an evolution in understanding sexual autonomy, striving to foster a more just and protective legal environment for victims of SV.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a comparative and qualitative approach to analyze the different SV legislations in European countries. The aim is to identify the main differences and similarities in the regulations and to evaluate the impact of these laws on society.

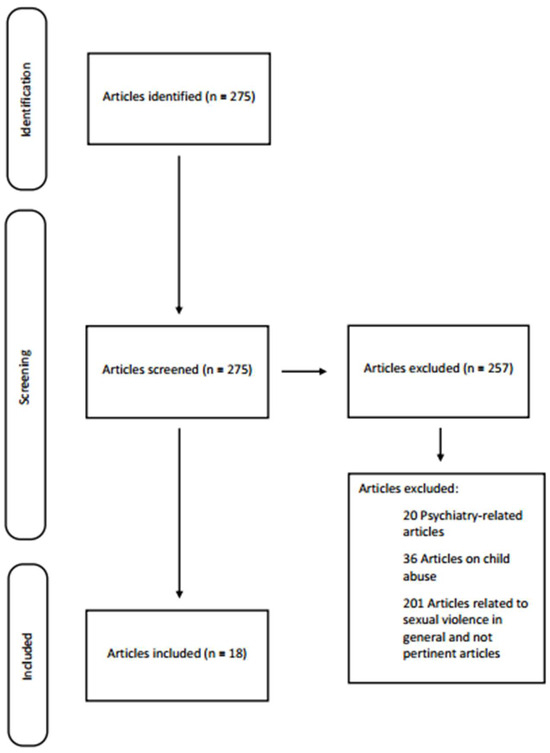

A review of currently published studies was performed following the PRISMA criteria [25]. A completed PRISMA checklist is available in Supplementary Table S1. The literature search was conducted via PubMed and Scopus, and it was carried out for articles published from 2015 onward using the following keywords terms: ((sexual violence) AND (Europe) AND (law)). Additionally, data were collected through a systematic review of online legislative documents, government reports, and publications from non-governmental organizations. Only documents published between 2015 and 2024 were included to ensure the relevance and currency the information. This initial electronic data search yielded a total of 275 potentially relevant studies. The articles were carefully evaluated based on their title, abstracts, and full texts. Implementation of these procedures resulted in 18 eligible papers for inclusion from the initial 275 articles within this search (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search strategy following PRISMA criteria.

Additionally, a systematic review of online legislative documents, government reports, and publications from non-governmental organizations was conducted to collect comprehensive data. This search specifically targeted documents published between 2015 and 2024 to ensure the relevance and currency of the information. For this systematic review of online legislative documents, the following search strategy was employed:

- search locations: official government websites of EU member countries, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom; official parliamentary and legislative databases (e.g., EUR-Lex for EU legislation); websites of national ministries of justice; official websites of non-governmental organizations focusing on human rights and gender equality (e.g., Amnesty International); and legal databases specializing in national legislation;

- search terms: combinations of terms such as “sexual violence law”, “rape legislation”, “sexual assault statutes”, “criminal code sexual offenses”, “gender-based violence law”, and “victim protection sexual violence”, translated into the official languages of the respective countries where appropriate;

- screening process: documents were initially screened based on titles and descriptions for direct relevance to SV legislation. Full-text documents were then assessed for their focus on legal frameworks, definitions of offenses, penalties, and victim support mechanisms related to sexual violence;

- exclusion criteria: documents that did not directly address SV legislation (e.g., focusing solely on prevention campaigns without legal details, purely sociological studies without legal analysis, or general human rights reports not specific to SV law) were excluded. The study included member countries of the EU, Switzerland and United Kingdom. Countries with incomplete or unavailable legislation were excluded. Additionally, articles that did not specifically address the topic of SV laws were excluded. Articles on psychiatric topics and articles related to child abuse have also been excluded.

Furthermore, direct reference to criminal codes of the included countries was prioritized during the search for legislative documents. While searching online legislative documents, a concerted effort was made to identify and include the main legislative documents, particularly the national criminal codes or equivalent penal statutes, that define and regulate sexual offenses within each given country. This ensured that the primary legal frameworks governing SV were accurately represented and analyzed.

3. Results

Several European legal systems were analyzed (Table 1 and Table 2), primarily through the examination of 18 articles. In Europe, it is estimated that one third of women had experienced at least one physical or SV after their 15 [26]. Based on figures collected up to 2021 by Eurostat, Sweden has the highest incidence of SV cases, exceeding 200 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, followed by France with over 100 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [27].

Table 1.

European legal systems analyzed.

Table 2.

European legal systems analyzed.

The pervasive nature of SV has prompted various countries in the EU, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom to implement a series of regulations designed to curb and containing the commission of this crime. Notably, the EU has adopted Directive EU 2024/1385 on fighting violence against women and domestic violence, which is mandated to be transposed by EU Member States by 2027. This comprehensive directive includes also measures to prevent online violence and the non-consensual sharing of intimate images [28]. Furthermore, Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, Ireland, Denmark, Switzerland, Norway, Finland, and the United Kingdom have collectively ratified the Istanbul Convention (IC). Developed as the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and fighting violence against women and domestic violence, this international treaty was formally approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 7 April 2011. Its core objectives are to prevent violence, protect victims, and hold perpetrators accountable. Notably, the IC represents a landmark legally binding international instrument that establishes a comprehensive legal framework to protect women against all forms of violence [29], and focuses on the prevention of domestic violence, the protection of victims, and the prosecution of perpetrators. According to the IC, violence against women is considered a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination (Article 3(a) of the IC). Countries should exercise due diligence to prevent violence, protect victims, and prosecute perpetrators (Article 5 of the IC). The IC is the first international treaty to include a definition of gender. Indeed, Article 3 of the IC defines gender as “socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men”.

Moreover, the treaty establishes a series of offenses characterized by violence against women. States should include these in their criminal codes or other forms of legislation or incorporate them if not already present in their legal systems. The offenses defined by the IC include psychological violence (Article 33 of the IC), stalking (Article 34 of the IC), physical violence (Article 35 of the IC), SV, including rape (Article 36 of the IC), forced marriage (Article 37 of the IC), female genital mutilation (Article 38 of the IC), forced abortion and forced sterilization (Article 39 of the IC), and sexual harassment (Article 40 of the IC) [30].

Considering this, at present, the only framework that would truly unite and apply to all EU members, Switzerland, and the UK is the Council of Europe’s European Convention on Human Rights. International human rights law provides a means to address how state authorities treat rape victims, offering a sense of justice when domestic remedies have failed. These mechanisms carry significant symbolic and normative power, leading to reforms in rape laws and practices across various domestic jurisdictions.

A landmark example of the ECHR’s impact is the case of M.C. v. Bulgaria (2003) [31]. The case of M.C. v. Bulgaria concerned a 14-year-old alleged rape victim. Bulgarian authorities concluded that insufficient evidence of compulsion existed, finding no force was used, and thus, no rape had occurred. The victim subsequently argued before the European Court of Human Rights that Bulgarian law inadequately protected her by requiring proof of force for rape, a stricter standard than in jurisdictions where non-consent alone sufficed. She also challenged the investigation’s thoroughness.

The ECtHR ruled that Bulgaria had violated its positive obligations under Articles 3 (prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment) and 8 (right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Court ordered Bulgaria to pay the victim non-pecuniary damages and costs. This judgment underscored the importance of consent in sexual assault cases, signaling a shift away from the sole requirement of physical force.

This pivotal judgment established the critical obligation for states to assess the absence of consent, even in situations where physical resistance was not present. This significantly strengthened the international legal framework concerning SV by moving beyond a narrow interpretation of resistance [32].

However, international human rights law has its limitations. Certain procedures and enforcement mechanisms can sometimes fall short of providing comprehensive protection. The interpretation of rights may vary, resulting in different levels of protection for victims. Furthermore, addressing cultural norms remains a challenge. As a result, international human rights law has not fully realized its potential to address all issues effectively [33].

3.1. Austria

The Austrian legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes not only physical contact but also acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. Indeed, the Austrian Criminal Code is aimed at protecting self-determination and safeguarding the most vulnerable categories [34].

The Austrian Criminal Code addresses a wide range of crimes, from sexual abuse of minors to sexual coercion, establishing a sanctioning system that grades the severity of the offense according to various parameters. Importance is given to laws that protect individuals in dependent positions, such as minors, people entrusted to institutions, prisoners, and patients with mental or physical disabilities (Sections 174a of Chapter 13 of the Austrian Criminal Code). In the sections dedicated to sexual abuse, the Austrian legislator introduces precise distinctions: the criminal treatment differs for acts committed against minors under 14 years of age compared to those against minors between 14 and 16 years, with penalties ranging from six months to ten years of imprisonment in the most serious cases. The most serious offenses include specific aggravating factors, such as penetration, involvement of multiple aggressors, or endangerment of the victim’s psychological and physical health (Sections 174 of Chapter 13 of the Austrian Criminal Code).

A significant chapter concerns the repression of prostitution and human trafficking, with regulations that punish not only direct acts of exploitation but also conduct such as mediation or inducement to prostitution (Sections 180a, 180b, 181, 181a of the Austrian Criminal Code).

Noteworthy is the introduction in 2006 of the crime of stalking, which sanctions persecutory behaviors such as persistent harassment, obsessive calls, and spreading defamatory rumors. The law provides for penalties of up to three years, taking into account the duration and psychological consequences of the perpetrator’s conduct [35].

Thus, the Austrian legal approach combines stringent sanctions with contextual evaluation, prioritizing a logic that not only focuses on punishing the offender but also on the effective protection of victims. The legislation also includes procedural mechanisms such as preliminary injunctions, which provide immediate and preventive protection for individuals at risk, effectively anticipating the judicial response to the commission of the crime. Hence, this system demonstrates attentiveness to the protection of vulnerable individuals and a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of SV.

3.2. Belgium

The Belgian legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed against a person’s will, regardless of the relationship with the victim and the context in which it occurs [36]. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts.

In Belgium, the current legislation on SV has recently been strengthened to ensure greater protection for victims. The new regulations emphasize consent as a fundamental element and introduce harsher penalties for SV offenses, considering the circumstances in which the crime occurs, such as the victim’s vulnerability. Belgian law defines consent as explicit and voluntary agreement, eliminating any ambiguity that could arise from silence or lack of physical resistance. This approach aims to better protect victims and ensure that perpetrators are adequately punished.

Additionally, Belgium has adopted specific measures against stalking and revenge porn. Since 2007, stalking has been regulated by Article 442bis of the Belgian Criminal Code, which provides severe penalties for anyone who harasses another person in a way that causes fear or anxiety. This legislation was introduced to address the growing problem of stalking and to provide adequate legal protection for victims.

Concerning revenge porn, Belgium introduced specific legislation in 2016, which criminalizes the non-consensual distribution of sexually explicit images or videos. This law provides prison sentences of up to five years for offenders and aims to protect the privacy and dignity of the victims. These measures reflect a cultural shift in the perception of SV and aim to recognize and respect the rights of victims. Belgian legislation has been influenced by studies and research highlighting the importance of a comprehensive and supportive approach to victims of SV. For instance, the 2019 report by the European Institute for Gender Equality [37] highlights the importance of specific laws against stalking to protect victims and prevent further abuse.

3.3. Denmark

The Danish legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s freely given consent. This includes not only physical contact but also acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts [38]. Denmark reformed its SV law to base it on consent rather than physical violence or threats [39]. This change was made to better align with international standards and to ensure greater protection for victims [40].

Chapter 25 of the Danish Criminal Code, Articles 244–246, regulate physical assaults, providing penalties ranging from three to ten years of imprisonment depending on the severity of the act and the consequences for the victim. Chapter 24 of the Danish Criminal Code, dedicated to sexual offenses, establishes a detailed regulatory framework that punishes rape with penalties of up to eight years, extendable to twelve in specific cases such as involvement of minors or particularly aggravating circumstances.

Furthermore, the reform of the Danish Criminal Code introduced significant changes to the legal framework concerning sexual offenses, with a particular focus on the concept of consent. This reform was inspired by the women’s rights movement and the need to improve the protection of sexual integrity and the dignity of victims [41]. One of the most significant changes was the introduction of the concept of NR [42]. This concept punishes those who commit a sexual act by taking advantage of the victim’s vulnerability, for instance, when the victim is under the influence of alcohol or drugs [43]. The reform shifted the focus from the requirement of physical violence to the principle of consent, recognizing that the lack of consent is sufficient to constitute the crime of rape [41]. The reform aims to ensure that these cases are treated with the severity they deserve, recognizing that the victim’s vulnerability should not be an opportunity for the perpetrator [44]. The reform represented a significant step towards greater protection for victims of SV and a more modern and sensitive approach to the issues of consent and vulnerability [41].

The Danish government has also initiated measures to improve support for victims, promoting the training of judicial operators and awareness programs against gender stereotypes. These efforts aim to create a more effective and human legal response to sexual offenses.

3.4. Finland

The Finnish legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. Finland has recently reformed its sexual offense law, placing particular emphasis on sexual self-determination and personal integrity. The new legislation, which came into force in January 2023, underscores the necessity of voluntary participation in sexual acts.

Chapter 20 of the Finnish Criminal Code [45] provides for the offense of rape and aggravated rape, differentiating the severity based on the violence perpetrated by the aggressor. Specifically, Section 1 of Chapter 20 of the Finnish Criminal Code states that anyone who has sexual intercourse with a person who does not voluntarily participate is punishable by imprisonment for one to six years. Chapter 20 of the Finnish Criminal Code also asserts that participation in the sexual act cannot be considered voluntary if the person has not expressed their voluntary participation verbally, through their behavior, or otherwise. Participation in sexual act cannot be considered voluntary if the person has been forced into sexual intercourse through violence or threats, or could not express their will due to ignorance, illness, disability, state of fear, intoxication, altered state of consciousness, suddenness of the situation, or severe abuse of power by the aggressor. There is also a penalty for attempted SV.

Section 2 of Chapter 20 of the Finnish Criminal Code addresses aggravated rape. Aggravated rape is defined when severe violence is used or threatened against the victim, or when serious physical injuries are caused, or the victim’s life is endangered. Aggravated rape is also defined if the crime is committed by multiple persons, if it causes particularly significant psychological and physical suffering, if it is committed in a particularly brutal, cruel, or humiliating manner, or if the victim is under 18 years of age. Attempted aggravated rape is also punishable.

Since 2014, stalking has been a criminal offense in Finland. The law defines stalking as repeatedly contacting someone without their permission, following, monitoring, and similar disruptive behaviors. These actions cause fear and anxiety in the victim [46].

Regarding sex education, Sexuality education in Finland is part of the national core curriculum and is integrated into various subjects in primary and secondary schools [47].

3.5. France

The French legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. French law emphasizes that consent must be freely given and not obtained through coercion, threats, or abuse of power. It can also be revoked at any time.

Article 212 of the French Civil Code introduced in 2006 the principle of respect as a fundamental element of the matrimonial institution. Article 515-9 of the French Civil Code also provides for protection orders for victims of domestic violence. The penal framework has progressively developed through significant legislative amendments. In 1992, Article 222-33 of the French Criminal Code introduced the offense of sexual harassment, subsequently strengthened by legislative changes. In 2006, Articles 132–180 and following of the French Criminal Code established domestic violence and SV as aggravating circumstances, providing for life imprisonment in cases of the victim’s death [48]. Law No. 2066-399 of 2006 introduced measures for the removal of the violent spouse and socio-health treatment. In 2010, the offenses of psychological violence and mobbing were introduced, with the implementation of protection orders initially lasting four months. The 2014 Gender Equality Act extended the protection order to six months and strengthened protective measures in the workplace.

Since 2005, the French government has implemented five strategic plans (2005–2019), with a total investment of over 125 million euros, aimed at protecting victims, preventing SV, raising awareness, and educating the population on the issue, combating sexism, and supporting victims in various social contexts. The recently introduced innovative aspects have included exceptions to confidentiality in cases of immediate danger [49], the qualification of sexual relations between adults and minors under 15 years of age as SV [50] and specialized training for judicial and socio-health operators. The evolution of French legislation represents a significant model of an integrated approach to gender protection, combining legislative, educational, and social interventions.

3.6. Germany

The German legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. The Fifty-Fifth Amendment to the German Criminal Code, dated 4 November 2016, titled “Strengthening the Protection of Sexual Self-Determination”, introduced significant innovations in sexual offenses [51]. This law redefines sexual offenses, moving beyond the previous paradigm that required explicit violence or threat.

Article 177, paragraph 1, of the German Criminal Code [52] stipulates that a sexual act committed against the clear and expressed will of the victim is punishable by imprisonment of six months to five years, substantially expanding criminal protection.

The amendment articulates multiple criminal offenses, including sexual acts committed with threats or by surprise, violence against individuals with infirmities or disabilities, abuse in situations exploiting the victim’s weakness, rape and group sexual acts, as well as violence involving the use of weapons or dangerous instruments. The penalties vary, with imprisonment ranging from up to 2 years for sexual harassment to 5–15 years for particularly heinous crimes (e.g., aggravated rape, SV against minors, SV against persons with disabilities, SV causing serious injury and murder connected to SV).

Moreover, a multidimensional action plan was implemented in 2007, focusing on the prevention and combating of violence, with specific protection for vulnerable categories such as migrant women, women with disabilities, and minors, enhancing victim assistance and promoting the rehabilitation of offenders.

The most innovative elements of the reform lie in its proactive approach towards marginalized groups, integrated psycho-social support, and the sensitization of health and judicial operators. The law, thus, represents a significant advancement in the protection of sexual self-determination, configuring an organic intervention model that goes beyond merely punitive logic to embrace a more comprehensive vision of individual rights protection.

The regulatory framework also includes specific provisions on stalking, contemplated in Article 238 of the German Criminal Code, which sanctions persecutory behaviors such as obsessive physical proximity, intimidation, and unwanted contacts through telecommunications, further expanding criminal protection against conduct that infringes on personal freedom.

3.7. Greece

The Greek legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s freely given consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts.

Chapter 19 of the Greek Criminal Code [53] represents a structured and detailed regulatory framework for the protection of sexual freedom, with particular attention to the protection of vulnerable subjects. The legislation defines a complex range of sexual offenses, from rape to the abuse of minors, establishing a sanctioning system graded based on the severity of the conduct and the characteristics of the victims.

The 2019 reform marks a crucial shift in the legal approach, aligning with the IC by introducing the principle of consent as a central element in the definition of rape. This legislative evolution moves beyond the previous paradigm based solely on the use of force, recognizing SV as a violation of human rights regardless of the methods of coercion [54].

The articles of the Greek Criminal Code address a wide spectrum of criminal conduct: from sexual abuse in institutional contexts (Articles 342–343 of the Greek Criminal Code) to human trafficking (Article 351 of the Greek Criminal Code), from child pornography (Article 348A of the Greek Criminal Code) to online grooming (Article 348B of the Greek Criminal Code). The legislation introduces differentiated custodial sentences, with increased penalties for crimes committed against minors or under aggravating circumstances.

Innovative aspects include the attention to the psychological dimension, with the provision for diagnostic examinations for both the perpetrator and the victim (Article 352A of the Greek Criminal Code) and specific protection measures for minors, such as the prohibition of disclosing their identity (Article 352B of the Greek Criminal Code).

The legislation reflects a holistic approach to sexual protection, which goes beyond the merely punitive dimension to embrace perspectives of prevention, protection, and rehabilitation, focusing on respect for personal integrity and the protection of the most vulnerable subjects.

3.8. Ireland

The Irish legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. Irish law clearly states that consent must be given freely and voluntarily, and can be revoked at any time [55,56].

Irish legislation on SV has undergone a profound transformation in recent decades, reflecting a substantial shift in the legal and social understanding of sexual offenses. The Sexual Offences Act of 2017 represents a crucial turning point in the national legislative landscape, introducing more precise and articulated definitions of consent, overcoming previous restrictive interpretations that often placed the burden on victims to prove non-consent.

The new law establishes that consent must be explicitly and freely given, definitively eliminating interpretations that considered silence or the absence of physical resistance as implicit forms of assent. This highlights how the Irish approach is at the forefront of protecting the rights of victims of SV, introducing a broader and more protective conception of consent.

The legislative text [57] significantly expands the scope of legal protection by introducing new categories of offenses and providing for harsher penalties. The Commission for Support Services for Victims of Sexual Assault [58] has played a crucial role in supporting the implementation of these legislative changes, providing assistance and counseling to victims.

The Irish legislative approach indeed adopts a gender-sensitive perspective, recognizing the systemic nature of SV. As highlighted in the annual report available on the government website [59], the legislative approach aims to dismantle cultural structures that traditionally minimize these offenses.

Moreover, Ireland has introduced specific laws against stalking and revenge porn. Since 2022, the “Criminal Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill 2022” [60] regulates stalking, with severe penalties for repeated acts of persecution. The law also allows the issuance of restraining orders without the need for a criminal conviction.

Regarding revenge porn, the “Harassment, Harmful Communications and Related Offences Act 2020” [61], known as “Coco’s Law”, punishes the non-consensual distribution of intimate images or videos, with prison sentences of up to seven years.

3.9. Italy

The Italian legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed with violence, threats, or abuse of authority. This includes sexual acts committed without the victim’s consent, exploiting their physical or mental inferiority, or deceiving them by assuming a false identity [62].

Law No. 66 of 1996 [63] reclassifies SV from a crime against public morality to a crime against the person. The legislative framework defines a broad concept of “sexual acts”, progressively developing an extensive interpretation, based on the compromise of the victim’s sexual self-determination. The law introduces a gradation of criminal offenses, with particular attention to vulnerable victims: minors, individuals in a state of physical or mental inferiority, persons subject to relationships of authority (Article 609 bis, Article 609 ter and Article 609 quarter of the Italian Criminal Code). Prosecution is generally upon complaint by the victim (Article 609 septies of the Italian Criminal Code), with exceptions that mandate criminal action in specific cases, such as crimes committed against minors under eighteen, crimes committed against minors entrusted for care, education, instruction, supervision, and custody, SV committed against a person incapable due to age or infirmity, aggravated SV involving the use of weapons, group SV, crimes committed by public officials, and cases where SV is connected to another crime prosecutable ex officio.

Jurisprudential evolution has progressively expanded the notion of “sexual act”, encompassing conduct not immediately attributable to sexual acts in the strict sense, provided they compromise sexual self-determination. Indeed, Italian jurisprudence defines the sexual act broadly and articulately, considering various aspects. According to Article 609-bis of the Italian Criminal Code, a sexual act includes any behavior involving physical contact with the victim’s erogenous zones, aimed at satisfying the aggressor’s libido. This can include not only complete sexual intercourse but also acts of lust such as kisses, caresses, or touches, if performed with the intent to excite or satisfy sexual desire. The Italian Court of Cassation clarifies that a sexual act includes not only direct contact with genital areas but also other forms of physical contact with sexual connotations, like kisses or fondling. Italian jurisprudence evaluates each case based on circumstances and intent. Undue physical intrusion can involve touching non-erogenous parts if they have sexual connotations. Examples include groping buttocks (judgment no. 5515/2016 of the Third Criminal Section of the Italian Court of Cassation), rubbing the penis against the victim’s body (judgment no. 17382/2021 of the Third Criminal Section of the Italian Court of Cassation), or ejaculating on the victim’s abdomen without genital contact (judgment no. 51083/2017 of the Third Criminal Section of the Italian Court of Cassation) [64].

The legislation also extends to other related offenses, such as the crime of stalking (Article 612bis of the Italian Criminal Code), the non-consensual dissemination of intimate images (Article 612ter of the Italian Criminal Code), and conduct that compromises moral freedom through threats or intimidation. A qualifying element is the enhanced protection for the most vulnerable victims, with an approach that combines criminal repression and the protection of personal dignity.

The Italian legislative framework confirms a cultural and legal evolution that places sexual freedom as a fundamental legal right, moving beyond moralistic perspectives and introducing more comprehensive and effective criminal protection.

3.10. Luxembourg

In Luxembourg, SV is defined as a sexual act without consent. This means that any sexual intercourse without the explicit consent of the involved person is considered rape [65].

On 7 August 2023, Luxembourg enacted a law aimed at strengthening measures to combat sexual abuse and the sexual exploitation of minors [66]. The law stipulates that consent to a sexual act must be assessed on a case-by-case basis and cannot be inferred from the victim’s lack of resistance. Consent can be withdrawn at any time. Minors under the age of sixteen are considered incapable of giving consent, with some exceptions for minors between thirteen and sixteen years old, if the age difference with the other person does not exceed four years.

Violations of sexual integrity are severely punished. Without violence or threat, penalties range from one month to two years of imprisonment and fines up to 10,000 euros. With violence or threat, penalties can be up to five years of imprisonment and fines up to 20,000 euros. For victims under sixteen, penalties increase to up to ten years of imprisonment and fines up to 50,000 euros.

Article 372ter of the Luxembourg Criminal Code states that violations against minors or with their assistance result in five to ten years of imprisonment and fines from 251 to 75,000 euros. The same applies if committed by a parent or authority figure. With violence or threat, penalties range from fifteen to twenty years of imprisonment, and for victims under thirteen, from twenty to thirty years.

Article 375 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code defines rape as any act of sexual penetration committed against a person who does not consent, and it will be punished with imprisonment from five to ten years. Articles 375bis and 375ter of the Luxembourg Criminal Code stipulate that any act of sexual penetration committed against a minor under sixteen years old will be punished with imprisonment from ten to fifteen years, and if committed by a parent or a person in authority over the minor victim, the penalty will be imprisonment from twenty to thirty years.

Article 376 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code increases the penalties if the rape has caused illness, permanent incapacity for work, or the death of the victim, with penalties ranging from ten years of imprisonment to life imprisonment. Article 377 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code provides that the minimum penalties for sexual offenses can be increased, and the maximum penalties can be doubled in certain circumstances, such as when the offense is committed by a person in authority over the victim or with the use of weapons or threats.

Finally, Article 383bis of the Luxembourg Criminal Code stipulates that the production, transportation, dissemination, or trade of violent or pornographic messages involving minors or particularly vulnerable persons will be punished with imprisonment from one to five years and a fine ranging from 251 to 75,000 euros.

Harassment and stalking are covered under Article 442-2 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code and the law of 11 August 1982, on privacy, which applies when a person is constantly subjected to telephone harassment. Defamatory, slanderous statements and insults are regulated by the law of 8 June 2004, while invasion of privacy is governed by the law of 11 August 1982, which provides penalties for the publication of photos or videos without the consent of the person concerned. Data protection is ensured by the law of 2 July 2007, and the protection of children and minors is regulated by the law of 16 July 2011. Racist or discriminatory comments are punished under Article 457-1 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code. Additionally, cybercrime, including hacking, is governed by Article 509-1 and following of the Luxembourg Penal Code and applies when someone illegally accesses another person’s computer or smartphone [67].

Regarding the teaching of sexual education in Luxembourg schools, it is not mandatory but is left to the discretion of the teachers [68].

3.11. Netherlands

The Dutch legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. The new sexual offenses law, which came into force on 1 July 2024, defines consent as clear and continuous, requiring respect for any sign of refusal, even non-verbal [69,70]. The law provides for harsher penalties for non-consensual sexual acts and has eliminated the need to prove the use of force to obtain a conviction for rape or sexual assault [70].

Dutch legislation on SV has made significant recent progress. With the approval on 1 July 2024, sex without consent is now definitively recognized as rape, marking an important step forward in the prevention and combating of SV [71]. Additionally, the Netherlands has introduced specific measures against stalking through Article 285b of the Dutch Criminal Code, which defines and penalizes persecutory conduct [72]. Regarding revenge porn, Dutch legislation severely punishes the non-consensual distribution of intimate images or videos, thus ensuring greater protection for victims of this crime. These legislative developments reflect a growing commitment to protecting victims’ rights and promoting a culture of consent and safety [71,73].

3.12. Norway

The Norwegian legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes obtaining sexual activity through violence or threatening behavior, engaging in sexual activity with a person who is unconscious or unable to resist, or forcing a person to engage in sexual activity with another person [74].

The Norwegian Criminal Code regulates different types of violence ranging from simple assault, where the victim need not have necessarily felt pain, to aggravated assault and personal injuries, whether simple or aggravated, depending on how the crime is committed.

Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code deals with sexual offenses. Section 291 of the Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code defines SV and establishes a penalty of up to 10 years’ imprisonment for any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. Section 292 of the Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code specifies that the minimum penalty for an SV act involving penetration ranges from 3 to 15 years, even if the act is committed using force or threats.

Section 293 of the Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code introduces aggravating circumstances, which carry a penalty of up to 21 years. These circumstances include cases where the victim is particularly vulnerable or when the act is particularly brutal. Additionally, Section 294 of the Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code addresses gross negligence in SV, punishable by imprisonment for up to 6 years. This provision applies when the perpetrator has not taken the necessary precautions to ensure the victim’s consent.

Finally, Section 295 of the Chapter 26 of the Norwegian Criminal Code deals with the abuse of a power relationship, punishable by imprisonment for up to 6 years. This section includes situations where the perpetrator exploits a position of authority or trust to commit sexual acts.

Norway was the first European state to introduce the definition of NR. NR is covered by Section 294 of the Norwegian Criminal Code, in its second paragraph, where the notion of the crime extends to both the person who knowingly commits sexual abuse and the person who should know they are committing rape (gross negligence). The penalty imposed is 5 years of imprisonment, which can be increased to 8 years with the application of aggravating circumstances.

3.13. Portugal

The Portuguese legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. This includes acts of coercion, threats, or abuse of power to obtain sexual acts. Portuguese law clearly states that consent must be given freely and voluntarily and can be revoked at any time [75].

Portuguese legislation on sexual offenses protects sexual freedom and personal integrity through a layered criminal framework established within the Criminal Code and bolstered by the ratification of the IC in 2013. The legislative framework is characterized by a protective vision that considers the peculiarities of different situations of SV, modulating the sanctioning frameworks in relation to the severity of the conduct and the specific circumstances.

Articles 163 to 177 of the Portuguese Criminal Code [76] define an articulated sanctioning system that covers multiple criminal hypotheses: from sexual coercion to rape, from the abuse of vulnerable subjects to the facilitation of prostitution, to the specific protection of minors. A qualifying element is the provision of aggravating factors related to the abuse of authority, hierarchical and family relationships, as well as conditions of economic or work dependency.

Particularly significant is the protection of minors, with offenses that differentiate conduct based on the age of the victim and the methods of abuse. The penalties, consequently, vary from one to ten years of imprisonment, considering the intrinsic severity of the act and the personal and social consequences. An innovative aspect is the provision of accessory measures that may involve the prohibition from exercising professions in contact with minors, demonstrating an approach that goes beyond the merely punitive dimension and aims at preventing further harmful conduct. The legislation also provides for flexible procedural mechanisms, such as the possibility of temporarily suspending proceedings for offenses against the sexual freedom of minors, balancing the need for protection with considerations of judicial opportunity. The overall framework reveals a modern conception of criminal protection, which goes beyond the merely repressive logic to embrace a perspective of integral protection of vulnerable subjects, with particular attention to the dynamics of abuse and the psychosocial consequences of SV. Portuguese legislation thus constitutes an advanced regulatory system, combining sanctioning rigor, attention to the specificities of contexts, and prevention objectives, configuring itself as a model of legal intervention on SV.

3.14. Spain

The Spanish legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent and establishes that consent must be clearly expressed. Any sexual act without explicit consent is considered sexual assault [77,78]. This change was introduced to facilitate the prosecution of aggressors and to guarantee greater protection for victims of SV [73].

The Spanish Organic Law 1/2004 [79] represents a turning point in the legal protection against gender violence, constituting an organic and multidimensional normative intervention that surpasses the traditional purely punitive approach. The legislation is based on the constitutional premise that gender violence constitutes a violation of fundamental rights, requiring public bodies to implement systemic protection measures. The legislative approach is innovative as it embraces a broad concept of violence, encompassing not only physical acts but also psychological ones, and recognizing as victims not only the directly affected women but also minors living in violence contexts. The normative framework is characterized by multi-level protection that develops through various instruments: an information and support system (such as the 016 Service), comprehensive social assistance, free legal aid, socio-labor reintegration pathways, and economic support measures [80].

Particularly significant is the protection framework that includes free legal assistance for victims at every procedural stage, specialized emergency services, psychological protection for victims and minors, the possibility of identity change in cases of extreme necessity, and economic aids for women in vulnerable conditions. The normative evolution found further development in 2022 with the “Only yes means yes” law, which introduces the principle of affirmative consent, eliminating traditional distinctions between abuse and sexual assault, and configuring any sexual act without explicit consent as SV [81].

Thus, the Spanish law is not merely a punitive tool but an integrated protection system that recognizes gender violence as a structural phenomenon requiring complex intervention from prevention to victim support. The normative framework reveals an advanced conception of human rights that recognizes gender violence as a social issue requiring articulated and multidisciplinary responses.

3.15. Sweden

The Swedish legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. Since 1 July 2018, Swedish legislation is based on the principle that all sexual acts must be voluntary. This means that consent must be clearly expressed and that any sexual act without explicit consent is considered SV [82,83].

The reform of Swedish Criminal Code in 2018 marked a fundamental change in the legal approach to sexual offenses, placing consent at the center of the definition of rape and other acts of SV, extensively revising Chapter 6 of the Swedish Criminal Code which deals with sexual offenses. Chapter 6 of the Swedish Criminal Code [84], which deals with sexual offenses, has been extensively revised. Section 1 of this chapter defines rape innovatively: instead of relying on the presence of violence or threats, the law considers rape any sexual act committed with a person who does not voluntarily participate. This shift in focus to the lack of consent represents a paradigmatic change in how the law addresses these crimes.

Swedish legislation introduced NR in Section 1a of the Chapter 6 of the Swedish Criminal Code. This new offense applies when a person engages in a sexual act without adequately ensuring that the other person is voluntarily participating. This provision aims to further hold individuals accountable for obtaining clear consent before engaging in sexual activities.

Section 2 of Chapter 6 of the Swedish Criminal Code addresses sexual abuse, covering sexual acts considered less severe than rape but still committed without the victim’s consent. This categorization allows for a proportionate legal response to a broader range of non-consensual sexual behaviors.

Particularly strict is the protection of minors. Section 4 of the Chapter 6 of Swedish Criminal Code establishes that any sexual act with a minor under 15 years old is automatically classified as rape, regardless of the circumstances or the alleged consent. This rule reflects Swedish society’s firm stance on protecting minors from sexual exploitation.

Section 10 of the Chapter 6 of the Swedish Criminal Code addresses sexual harassment, criminalizing unwanted sexual behaviors that violate an individual’s personal integrity. This provision acknowledges the harmful impact of a wide range of inappropriate sexual behaviors, even when they do not reach the level of direct physical contact.

Regarding penalties, the Swedish Criminal Code provides a range of sanctions from fines to imprisonment, with prison sentences of up to 10 years for the most severe cases of rape. This flexibility in sentencing allows courts to consider the specific circumstances of each case.

The Swedish approach is considered cutting-edge in Europe for its emphasis on active consent. This legislative change has effectively shifted the burden of proof: it is no longer the victim’s responsibility to prove resistance, but the accused’s responsibility to prove they obtained consent. This reflects a broader cultural shift in understanding power dynamics in sexual relationships and individual responsibility.

Moreover, Sweden has introduced sex education in schools, which is mandatory from elementary school onwards [85].

3.16. Switzerland

The Swiss legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. The law stipulates that consent must be clearly expressed and that any sexual act without explicit consent is considered SV [86].

Prior to the recent reforms, the Swiss legal framework included requirements for threats, force, or psychological pressure as preconditions for offenses classified as sexual coercion or rape. Additionally, the definition of rape was limited to non-consensual vaginal penetration of a woman by a man.

Effective 1 July 2024, a significant reform to the Swiss Criminal Code [86] addressed these limitations. This reform eliminated the previous requirement for victim resistance and force as a precondition, recognizing SV even in the absence of explicit consent. Furthermore, any non-consensual penetration—oral, vaginal, or anal—of a man or woman is now considered rape. This updated legislation introduces a gender-neutral definition of rape, grounded in the principle of consent and the violation of human rights.

This reform represents a nuanced approach to the thorny issue of consent, balancing different models of consent. While the House of Representatives favored an affirmative approach (“only yes means yes”), where consent is based on free will and passivity cannot be deemed consent (a model adopted by 14 EU countries to varying degrees), the Swiss Senate advocated for a “no means no” approach, requiring victims to express opposition verbally or through actions. Although “only yes means yes” is considered by many, including Irene Rosales, Policy and Campaigns Officer for the European Women’s Lobby, to better protect human rights principles of sexual autonomy and bodily integrity, the “no means no” solution ultimately prevailed in Switzerland.

However, the new law incorporates a crucial element: it considers the victim’s state of shock. If a victim is petrified with fear and unable to express refusal or defend themselves, the perpetrator can still be charged with rape or sexual assault and coercion [87].

Articles 187–191 and 198 of the Swiss Criminal Code broaden the scope of legal protection, addressing: sexual acts with minors, SV in contexts of dependency, and sexual coercion and harassment, including those perpetrated in digital environments. The legislation establishes a detailed sanctioning framework, with potential prison sentences of up to 10 years for the most severe offenses. It also incorporates evaluation criteria that consider the victim’s vulnerability and relational dynamics.

The Federal Victim Assistance Act is structured upon three fundamental pillars: counseling, financial compensation, and procedural support. This act acknowledges the right to assist not only for direct victims but also for their family members. Concurrently, the Swiss Sexual Health Foundation [88] plays a vital role in promoting sexual rights through multifaceted operations encompassing education, prevention, professional training, and institutional networking. Since 2022, the organization has intensified its efforts toward inclusive sexual education, addressing emerging challenges in sexual health within the digital age.

This comprehensive legislative reform demonstrates a holistic approach to the protection of sexual integrity, founded on respect for human rights and the prevention of violence.

3.17. United Kingdom

The United Kingdom legal system defines SV as any sexual act committed without the victim’s consent. The main law governing these offenses is the Sexual Offences Act 2003 [89]. The Sexual Offences Act 2003 includes various categories of sexual offenses, such as rape, sexual assault by penetration, sexual assault, and causing a person to engage in sexual activities without consent [90]. According to United Kingdom legal system, consent must be given freely and voluntarily and can be revoked at any time [91].

The United Kingdom’s criminal legislation in recent decades represents a systematic approach to preventing and combating gender-based violence, characterized by a multidimensional and technologically advanced normative intervention. The Sexual Offences Act of 2003 [92] provides the fundamental legislative framework for sexual offenses, introducing a broad concept of protection, with particular attention to the protection of minors and extending legal protection until the age of 18.

The legislation surpasses the purely punitive dimension, articulated in preventive and precautionary tools such as Sexual Harm Prevention Orders. The legislative evolution is characterized by a progressive extension of protections, as demonstrated by the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act of 2004, which extends protection to same-sex and non-cohabiting couples, and the Crime and Security Act of 2010, which gives judges articulated and immediate protective tools. Innovative aspects emerge from the introduction of new criminal offenses, such as stalking and “revenge porn,” and from an approach that assesses the seriousness of the offense in relation to relational dynamics and the victim’s vulnerability [93].

The British government has accompanied the legislative evolution with significant investments: £80 million for five-year interventions, £15 million annually for women’s support organizations, and a strategic focus on prevention through educational programs and cultural interventions. The technological aspect plays a crucial role: the use of micro-cameras, geolocation, and advanced tracking and data collection systems configures an intervention model that combines legal protection with technological innovation [94].

The overall strategy reveals a complex understanding of gender-based violence, which goes beyond the emergency logic to embrace a systemic approach: cultural prevention, victim support, judicial intervention, and technological monitoring are configured as interconnected dimensions of a structural project to combat violence. The Sentencing Council guidelines and legislative updates, such as those in 2024 on domestic violence and stalking offenses, testify to a dynamic and constantly updated approach to social and criminological evolutions [95].

The Sentencing Council guidelines of 2024, in fact, represent a significant turning point in British law for combating gender-based violence. Among the main novelties, the new guidelines for strangulation and suffocation offenses stand out, introduced to ensure that offenders receive penalties commensurate with the gravity of their acts, even in the absence of visible physical injuries. These guidelines recognize the intrinsic danger of such behaviors and the traumatic impact on victims. The guidelines for domestic violence and stalking have been updated to better reflect the complex dynamics of abusive relationships and the victims’ vulnerability. This update includes the introduction of mitigating factors and more detailed explanations for a range of offenses, to ensure that penalties are proportionate to the gravity of the offenses and the specific circumstances of each case. Parallelly, the British government has invested significant resources to support victims of domestic violence and stalking. These investments include £80 million for five-year interventions and £15 million annually to support women’s aid organizations. The objective is not only to provide immediate assistance but also to implement educational programs and cultural interventions aimed at preventing violence. Another crucial aspect of the British approach is the use of advanced technologies for victim protection. The adoption of micro-cameras, geolocation systems, and advanced tracking allows for more effective monitoring, improving the safety of victims and the ability of law enforcement to intervene promptly. The overall strategy reveals a comprehensive understanding of gender-based violence, which goes beyond the emergency logic and embraces a systemic approach. This includes cultural prevention, victim support, judicial intervention, and technological monitoring, configured as interconnected dimensions of a structural project to combat violence. The Sentencing Council guidelines and legislative updates, such as those of 2024 on domestic violence and stalking offenses, testify to a dynamic and constantly updated approach to social and criminological evolutions. This commitment to ongoing reform ensures the legal system remains responsive to the evolving nature of SV, prioritizing both victim support and appropriate punishment for perpetrators.

4. Discussion

The analysis of European laws on SV reveals a highly complex regulatory framework. Over the years, these laws have evolved, with the most significant transition being the shift from legal models focused solely on punishment, towards approaches that include victim protection, crime prevention, offender rehabilitation, and the safeguarding of individual rights [96]. To provide a comprehensive yet focused analysis, this article selectively examines certain EU member states that represent a diverse range of legal approaches and innovations in addressing SV. Therefore, the selected countries were chosen based on their pioneering reforms and distinctive legislative strategies that offer valuable insights into the evolving European landscape of SV legislation.

The principle of consent is at the core of these legislative changes. In fact, the laws introduced in Northern EU countries have radically changed the legal conception of SV. Sweden, with its 2018 reform, defined rape not as the presence of physical violence or explicit threat, but as the absence of conscious and voluntary consent. This change is not merely terminological but entails a significant redefinition of legal assessment, reversing the burden of proof and making individuals responsible for obtaining clear and prior consent. This evolution is also reflected in other countries. Finland, for instance, in 2011 expanded the concept of sexual coercion to include situations where the perpetrator exploits the victim’s vulnerability [45]. Denmark introduced the concept of NR which punishes behaviors that take advantage of the victim’s vulnerability without directly using physical force [97].

The protection of vulnerable individuals is increasingly central to European laws. Germany, with the 2016 law on “Strengthening the Protection of Sexual Self-Determination” expanded criminal protection to explicitly include abuses against people with disabilities or in situations of weakness or infirmity. The Portuguese approach is a model of differentiated protection. Indeed, the Portuguese Criminal Code introduces aggravating factors that consider relational dynamics, including not only physical violence but also abuses stemming from hierarchical, familial relationships or conditions of economic and labor dependency [76]. Similarly, the 2019 Greek law introduced provisions specifically protecting minors, including measures such as the prohibition of identity disclosure and the implementation of diagnostic examinations for both the perpetrator and the victim.

Technology is becoming increasingly important in intervention strategies. The British model is an advanced example of integration between legal protection and technological innovation. The use of micro-cameras, geolocation systems and tracking technologies serves not only for investigations but also for crime prevention and the active victims’ protection [94].

Victim support strategies are evolving towards more multidimensional models. For instance, the Spanish Organic Law 1/2004 created an integrated system that goes beyond the judicial aspect, including social assistance, free legal aid, job reintegration pathways, and economic support measures for victims. This approach acknowledges the complexity of trauma and the need for interventions that support victims in their personal and social recovery journeys.

Significant differences in penalties persist. The Swedish system stands out for its detailed classification of sexual offenses, with varying penalties depending on the factors involved. Norway introduced the category of NR with penalties of up to 8 years in prison, while Switzerland provides for penalties of up to 10 years for the most serious offenses.

A relevant aspect is the evolution of mechanisms for preventing SV. This includes not only repressive interventions but also awareness and training strategies. Sweden has introduced sex education mandatory from elementary school, creating a model of cultural prevention against gender violence.

Intersectionality is an important interpretative criterion. The most advanced laws recognize that sexual vulnerability is influenced by multiple factors: gender, age, disability, socioeconomic status, and ethnic background. The Swiss law, for instance, introduces a gender-neutral definition of rape, surpassing limited and discriminatory legal conceptions [98].