Abstract

The disappearance of foreign minors in Italy is a long-standing and critically underexamined social phenomenon. Despite alarming figures, public and institutional attention remains episodic and media-driven, often limited to high-profile or criminal cases. This study offers a socio-forensic analysis of official data from 2014 to 2023, revealing significant inconsistencies in how these cases are reported, categorized, and followed up by Italian institutions. It highlights how unaccompanied and migrant minors are especially vulnerable within a fragmented and reactive system that lacks transparency and effective preventive measures. Rather than presenting new empirical data, the article reinterprets existing sources to expose systemic gaps, drawing comparisons with the more structured approaches adopted in countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Spain. These international examples show how multilingual communication, early warning systems (e.g., AMBER Alert), and public geolocation tools can offer timely, coordinated responses to disappearances—tools that remain largely absent or underused in Italy. The article further argues for the integration of forensic geospatial methods, such as locus operandi analysis, remote sensing, and forensic geoarchaeology, not as experimental techniques, but as practical tools that could strengthen Italy’s institutional capacity to respond. Ultimately, this study seeks to elevate the discussion surrounding missing foreign minors from a marginal social concern to a matter of forensic and public interest, and to encourage interdisciplinary reflection on how such disappearances are framed—and too often dismissed—within the national landscape.

1. Introduction

The issue of missing persons in Italy is often addressed as an “emergency,” a label commonly applied to other pressing social challenges [1]. This perspective frames the problem as episodic and circumstantial, tied to individual cases that make headlines for a few days, such as a disappearance that captivates public attention, a shipwreck involving an unknown number of migrants, or escapes from detention centers for irregular migrants [2,3]. However, this approach obscures a critical truth: the phenomenon of missing persons is not an isolated emergency but a systemic issue that requires equally systemic measures implemented consistently, even when it is not in the news, using scientific methodologies like, for example, forensic geoarchaeology [4,5].

Public reports published on the website of the Italian Ministry of the Interior reflect the confusion surrounding the collection and analysis of relevant data. Navigating these reports is challenging, but they still offer insights into the trends and patterns of the phenomenon. This study aims to reanalyze and extract key findings from this data, focusing specifically on the disappearance of foreign minors in Italy between 2014 and 2023 [6]. Note that only the first semester of 2024 is currently available on the official website of the Italian Ministry of the Interior. For this reason, we have chosen to reference only datasets up to 2023, which are complete and ensure consistency and accuracy in our analysis.

The chosen time frame stems from the availability of biannual reports published by the Ministry of the Interior, starting in 2014. Earlier data, covering the years from 1974 to 2013, is presented in a less detailed, aggregate format that precludes semester-specific analysis. The focus on foreign minors reflects a unique characteristic of Italian data: it is divided not only by broad age categories but also by nationality (Italian vs. foreign). This distinction lacks substantive justification since it is not linked to specific policies or procedures related to nationality during search operations. Nevertheless, this peculiar division offers an opportunity to highlight the specific characteristics of the issue and propose tailored solutions [7,8,9,10].

1.1. Who Is a Missing Person, and What Happens When a Person Goes Missing in Italy?

The term “missing person” is defined as the state of disappearing, no longer being present, or being unreachable or untraceable, and, more specifically in legal terms, the absence of any information about a person’s whereabouts, with no evidence of their death [11]. This analysis includes all cases that fall within this definition, excluding the subcategory of persons who disappear due to war or natural disasters.

Italian law (Law No. 203 of 29 November 2012) provides a straightforward yet comprehensive framework for addressing the disappearance of individuals [12]. It outlines a process divided into three temporal phases:

- Before and during the report: Any person, without obligation, may report a disappearance in person at the nearest law enforcement office or by phone (since 2016), with in-person confirmation required within 72 h.

- After the report: The operational hierarchy activated includes the person reporting the disappearance, local police forces, regional emergency plans (involving fire brigades, forestry services, local health authorities, etc.), and the Office of the Special Commissioner for Missing Persons.

- Coordination and oversight: The Special Commissioner, established by Presidential Decree on 31 July 2007, acts as a liaison between state administrations and between families of the missing and the government. The Commissioner’s office, comprising Ministry of the Interior officials and police representatives, provides biannual updates on its activities.

Parallel to the administrative pathway, a judicial pathway is also activated, involving the magistrate’s office, which oversees criminal investigations related to the missing person. Additionally, non-governmental organizations and media outlets often play a pivotal role in raising awareness and contributing to search efforts [13,14].

1.2. Who Are Foreign Minors According to Italian Law?

Foreign minors are defined as individuals under 18 years of age without Italian citizenship. Within this group, “unaccompanied foreign minors” (known by the acronym MSNA) are particularly vulnerable. They are legally defined as minors who lack both citizenship and parental or adult representation in accordance with Italian law [15].

When unaccompanied foreign minors arrive in Italy, they are subject to an identification process governed by the Zampa Law (2017) and more recent amendments introduced by the 2023 Migration Decree. If there are doubts about a minor’s declared age, authorities first attempt to verify it through documentation. In the absence of reliable documents, medical examinations are conducted. The two legal frameworks differ significantly in this regard: the Zampa Law requires the presence of a cultural mediator and written authorization from the Juvenile Court, while the 2023 Migration Decree has reduced these safeguards, particularly during mass arrivals. The most recent biannual report from 2024, which includes preliminary age-specific breakdowns, confirms a longstanding trend: the majority of reported disappearances involve minors aged 15 to 17. This age group occupies a legally and socially ambiguous space—they are often close to adulthood, making age verification more challenging, and they may receive less consistent institutional support. Under Italian migration law, their treatment varies depending on fluctuating reception policies, identification procedures, and the availability of guardianship structures. These legal inconsistencies, combined with sociocultural factors such as language barriers, absence of familial networks, and psychological vulnerability, increase the risk that these minors will disengage from support systems or disappear entirely. The age profile, therefore, should not be seen as a neutral demographic characteristic, but rather as a marker of systemic exposure to abandonment, legal uncertainty, and inadequate institutional follow-up. [16].

This uncertainty regarding age assessment introduces a margin of error that complicates both the legal process and the present study. Medical methods, such as radiological exams (e.g., wrist X-rays), and anthropological methods (e.g., assessment of skeletal maturation and human anatomical variation) [17,18], are both used in Italy for age verification, but they are known to be imprecise sometimes, further exacerbating the issue [19,20].

1.3. Missing Foreign Minors: Who Responds When a Report Is Filed?

When a foreign minor goes missing, no distinct procedural differences exist compared to cases involving Italian minors, except in instances of international parental abduction. Support structures include resources like the website Missing Children Europe and the Telefono Azzurro helpline, which provides legal assistance, psychological support, and links to relevant services [21,22].

Prevention and community-based support are emphasized in initiatives such as the Miniila app, which offers multilingual practical and legal assistance to migrant minors. However, access to these tools often depends on the minors’ ability to navigate the support network, which remains a significant barrier [23].

By examining these processes and the challenges inherent in the system, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the issue of missing foreign minors in Italy and propose potential improvements to existing practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Foreign Nationals: Categories Vs. Reality

This section builds upon the foundational observations made in the introduction, aiming to address the phenomenon of missing persons in Italy and contextualize it within a broader scope. The approach combines deductive reasoning, moving from general to specific, and inductive reasoning, starting from localized analyses of individual countries to facilitate a transnational comparison.

As noted previously, Italy maintains a unique approach to data categorization by consistently dividing missing persons into two broad groups: Italian citizens and foreign nationals. This categorization permeates all levels of data presentation in official reports, with nearly all graphs and tables divided accordingly. While these macro-categories are treated equivalently in data representation, the thematic focus diverges significantly. Topics such as irregular migration, foreign nationals in reception centers, and individuals lost at sea during migratory crossings do not apply equally to both Italians and foreign nationals [21,24].

This divergence reveals a significant flaw in the collection and analysis of data related to foreign nationals. To address this, the annual reports from 2014 to 2023 were analyzed systematically (Figure 1). Each report was scored based on the distinctiveness of the information it provides, assigning one point for each unique type of data that could not otherwise be deduced from other figures. For instance, if a report includes a table that cross-references age and gender, each age range and gender combination was counted as unique information. Redundant data, such as pie charts derived from pre-existing tables, were not assigned additional points (Figure 2) [6]. To enhance transparency, a scoring matrix is included in Appendix A, illustrating the criteria used to define ‘unique data.’ For example, a chart that cross-references age and gender would be counted once for each novel combination, whereas visual derivatives of the same data were excluded. For instance, in 2020, a data table including the intersection of gender, age brackets, and nationality yielded three unique data layers, each assigned one point.

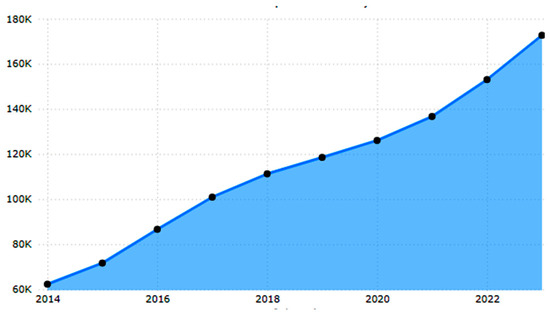

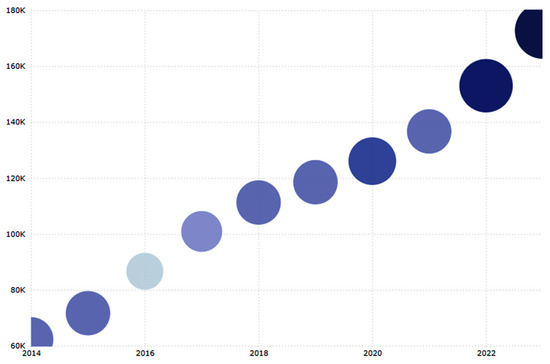

Figure 1.

Yearly number of missing persons of foreign nationality. Circle size denotes richness of reported data.

Figure 2.

Year-by-year trend (2014–2023): comparison between the increase in reports (y-axis) and the amount of information provided on foreign citizens in the annual reports, represented by the size and color of the circles denoting data depth.

2.1.1. Data Categorization by Year or Since 1974?

Annual reports frequently aggregate data from 1 January 1974, to 31 December of the reporting year. This method, unless supplemented with prior reports, makes it difficult to isolate yearly data and assess trends over time. However, in recent years, reports have increasingly provided annualized data with comparisons to the preceding two or three years, improving temporal clarity (Figure 3).

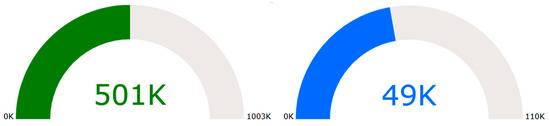

Figure 3.

Number of foreign individuals found, as reported by the Italian Ministry of the Interior. The green gauge represents the total number of foreign individuals found between 1974 and 2023 (approximately 501,000, out of over 1,000,000 reports), while the blue gauge shows those found in the last decade, 2014–2023 (approximately 49,000, out of 110,000 reports). Please note: the two gauges use different scales to allow clearer visualization of each time frame and are not intended to be compared proportionally.

2.1.2. “Unknown” and “Unknown Location” Categories

The category “unknown” introduces ambiguity when paired with “foreign nationals” in certain reports, as these “unknowns” are not separately quantified but are instead included in the foreign nationals’ totals. This raises two issues: the lack of a clear definition for the “unknown” category and the distortion of the foreign nationals’ statistics. Additionally, since 2018, the term “unknown location or state” (refers to cases where the geographic jurisdiction is unspecified at the time of reporting) has appeared, further complicating interpretation without adequate explanation. To improve the understanding of these ambiguous classifications, a glossary defining each term has been provided (Appendix B).

2.1.3. Migration-Related Disappearances

The “migration-related” category refers primarily to disappearances linked to migratory phenomena, such as individuals lost at sea. This data is inconsistently reported across years, making it impossible to track trends reliably. Furthermore, the category’s definition merges disparate issues, further complicating its analysis.

2.1.4. Foreign Nationals Abroad

The category “foreign nationals abroad” (refers to non-Italian citizens reported missing outside Italian territory, where Italy’s jurisdiction is limited) is as ambiguous as its counterpart, “Italians abroad”. It straddles two legal systems: Italian law and the laws of the foreign country where the report originates. Reports do not provide specifics on how Italy’s bureaucratic apparatus interacts with foreign legal systems during search efforts.

2.2. Comparative Analysis

This section examines data and methodologies from three countries—USA, Spain, and England—offering insights into their approaches to missing persons and their broader implications.

2.2.1. USA

The United States, described as having one of the highest numbers of missing persons globally, demonstrates a significant level of organizational capacity in its search efforts. The National Crime Information Center (NCIC), an FBI database, provides annual reports that categorize cases by age (adults vs. minors), sex, ethnicity, search status, and reasons for disappearance (e.g., disabilities, danger, involuntary circumstances). However, these reports are often too concise to allow comprehensive analysis [25].

A more promising resource is NamUs (National Missing and Unidentified Persons System), which compiles detailed monthly and annual reports, including breakdowns by state, city, sex, age, and ethnicity. Despite its comprehensiveness, NamUs faces challenges such as incomplete data from certain states and delayed updates.

For minors, the AMBER Alert system plays a crucial role. This platform broadcasts critical information about endangered children to the public through digital and traditional media. Since its inception in 1997, AMBER Alert has contributed to the recovery of over 1200 minors [26].

2.2.2. Spain

Spain’s Centro Nacional de Los Desaparecidos (CNDES) defines missing persons similarly to European standards, emphasizing safety concerns and the absence of known reasons for disappearance. The official website provides clear guidelines for reporting a missing person and presents data that can be filtered by year, region, sex, age, and search status [27].

Spain recognizes three official reasons for disappearance: voluntary, involuntary, and forced (e.g., abductions). For minors, Spain employs both the AMBER Alert system and the European 116,000 hotline, managed by the Fundación ANAR [28,29].

2.2.3. England

In England, data on missing persons is primarily managed by the Missing Persons Unit under the National Crime Agency (NCA). While public-facing information is concise and accessible, the official reports are often delayed and lack detail [30,31].

The UK also utilizes the AMBER Alert system for missing children and integrates modern tools like What3Words, a geolocation application that divides the globe into one-meter squares, assigning each a unique three-word identifier. This tool has proven invaluable, particularly in rural or remote areas [32,33,34].

2.2.4. Additional Considerations

The approaches outlined above reflect not only how these countries manage the issue of missing persons but also how they perceive it. Numerical comparisons between countries are challenging due to differences in population size and categorization methods. For example, while Italy maintains a broad category for “foreign nationals,” other countries provide more detailed classifications based on ethnicity and nationality [9]. Spain was selected as a comparative country due to its centralized national database, accessible bilingual interface, and documented use of child search systems such as AMBER Alert. While countries like Greece and Germany also offer valuable examples, the public-facing missing persons infrastructure in Greece is less detailed, and Germany is less relevant as it is not a Mediterranean country.

3. Results

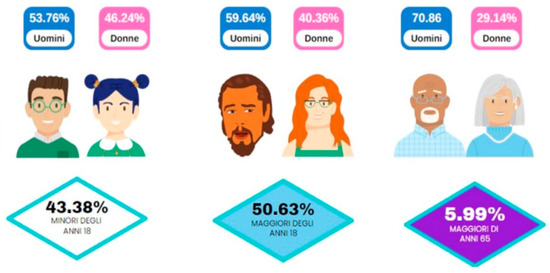

Missing Foreign Minors

The category of minors, encompassing individuals under 18 years of age, spans a wide range of developmental stages and capacities. A five-year-old child, for instance, is markedly different from a 16-year-old adolescent, regardless of nationality. Despite this, the reports analyzed (with the exception of 2020) group all minors aged 0–17 together [23]. The 2020 report offers a rare breakdown of data by age, although without distinguishing nationality. This breakdown reveals that 75.04% of reported cases involve minors aged 15–17, 19.53% fall within the 11–14 range, and 5.43% are under 11. This highlights the importance of accurately determining the age of minors, particularly for those classified as unaccompanied foreign minors (MSNA) [6].

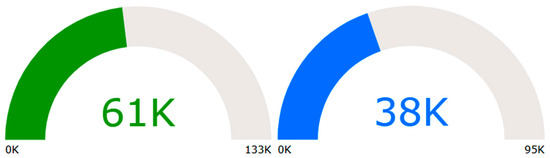

Having established this context, we turn to the data provided in the reports published by the Special Commissioners and the Ministry of the Interior. The overall figures (Figure 4) indicate that from 1 January 1974 to 31 December 2023, 132,559 foreign minors were reported missing in Italy, of whom 71,396 remain unaccounted for—a staggering 53.85%.

Figure 4.

Of the total number of reports, the data highlights the foreign minors found from 1974 to 2023 (in green) and over the past ten years (in blue, 2014–2023).

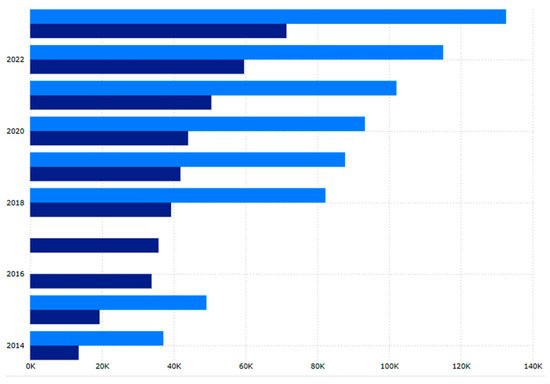

The data over time (Figure 5) reveal an increasing trend in the number of missing foreign minors, although some gaps in the data for specific years, such as 2016, prevent a complete year-by-year analysis. There appear to be periods of heightened activity, notably between 2015 and 2017 and again in 2023. Two key factors may explain these surges:

Figure 5.

Comparison between the number of reports (in light blue) and the number of persons found (in dark blue), with counts starting from 1974 and focusing on the past ten years (2014–2023), where data is available.

- Changes in reporting procedures: The 2016 implementation of phone-based initial reporting may have contributed to a rise in reported cases.

- Increased migration flows: A combination of increased migration and the legal provision (Law No. 203/2012) allowing non-relatives, such as shelter staff, to file reports may also account for the uptick.

Geographically, the data are inconsistent and incomplete, with most reports failing to distinguish between Italian and foreign minors or provide age-specific breakdowns. Between 2014 and 2018, overall regional data consistently highlight Lombardy, Lazio, Sicily, and Campania as regions with the highest number of missing persons. For 2019 and 2022, regional data differentiate between Italian and foreign minors, with Sicily, Lazio, and Lombardy dominating in both years. In 2020 and 2023, Sicily, Lombardy, Lazio, and Apulia emerge as the regions with the highest number of foreign minors reported missing.

These trends align with broader demographic realities: Sicily serves as a primary entry point for Mediterranean migration routes, while Lombardy, Lazio, and Campania are among the most populous regions and host significant foreign populations. Apulia is the destination point for routes from the Middle East and Balkan countries, increasingly affected in recent years by wars and/or political instability. A UNHCR report highlights Sicily’s unique position, noting that between 2017 and 2019, 40% of all unaccompanied foreign minors in Italy were located on the island [35].

The profiles of missing foreign minors remain nebulous due to the lack of detailed data. However, it is reasonable to assume that the category includes a mix of the following:

- Recently arrived minors recognized as unaccompanied.

- Individuals lost at sea, reported by survivors who reached Italy.

- Minors partially or fully integrated into Italian society.

- Tourists.

Available data on the reasons for disappearance are limited to reports up to 2018. For 2014–2015, cumulative data since 1974 reveal the following categories:

- Voluntary departures: 10,706 cases.

- Departures from institutions or shelters: 10,489 cases.

- Psychological disturbances: 8 cases.

- Abductions by a spouse: 383 cases.

- Potential victims of crime: 13 cases.

- Unknown reasons: 8992 cases (category discontinued after 2015).

- Departures from foster care/repatriation within Italy: 999 cases.

- Departures from foster care/monitoring abroad: 1177 cases.

These figures highlight systemic vulnerabilities in the very institutions intended to protect minors. The high incidence of disappearances from shelters and foster care underscores the risks these minors face, including exposure to criminal exploitation. Despite these alarming statistics, annual reports lack in-depth thematic analyses or actionable recommendations, either for prevention or post-disappearance intervention [36,37]. The absence of focus on these critical issues calls for urgent attention, particularly to address systemic weaknesses and propose targeted solutions.

4. Discussion

The challenges in obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the issue of missing persons in Italy stem not only from gaps in available data but also from a lack of focus on critical information that could offer clearer insights. Based on the analyses presented and the comparative studies of other countries, this section outlines proposals to address the different stages of the missing persons phenomenon in Italy.

4.1. Reporting and Perceived Motivations

One of the fundamental issues is the accessibility of information on what to do when a person goes missing. While the instinctive response is to approach the nearest law enforcement agency, this process becomes more complicated for those who do not speak Italian. Italy, ranked 26th out of 35 countries in English proficiency according to True Numbers [38], offers instructions exclusively in Italian on official Ministry of the Interior pages.

By contrast, the websites of other countries analyzed provide information in at least two languages, typically the national language and English. To address this, Italian authorities should include English as a second language on their websites and create a centralized page consolidating all key information and links to relevant organizations. This would make it easier for non-Italian speakers, particularly recent arrivals, to access essential resources [39]. Although recent literature has explored multilingual digital health systems, we focus here strictly on institutional forensic communication. This is consistent with recent findings that position missing minors as a public health and protection issue, rather than purely a criminal or administrative concern [40].

4.2. Search Efforts

Regarding missing foreign minors, prevention efforts should focus on the institutions from which many disappear. A systematic analysis of disappearances by geographic location, including mapping patterns, could guide both preventive and rapid response measures.

Once a missing person report is filed, search operations and support for the families or close contacts of the missing individual begin. Within the European Union, the hotline 116,000 serves as a foundational resource. However, these tools are largely passive and rely on external reporting. Active systems, such as the AMBER Alert used in the United States and other countries, could be implemented in Italy. AMBER Alert is a proactive and effective method not only for conducting searches but also for raising public awareness, cutting across language barriers [41].

For more active search methodologies, Italy could adopt tools like What3Words, which provides precise geolocation even in rural or remote areas. What3Words could be integrated into local and national emergency platforms (e.g., 112) with minimal infrastructural investment. Remote sensing techniques, already used in environmental monitoring, could be scaled through inter-agency training programs and existing civil protection units. Additionally, the locus operandi—a geographic profiling method originally developed for crime prevention—should be employed in missing persons investigations [42]. This approach uses geospatial data points (e.g., locations frequented by the missing person) to define search areas and conduct targeted searches from the outset [31,43,44].

While traditionally associated with criminal investigations and historical human remains, forensic geoarchaeology can also be a critical asset in the early stages of missing person investigations. In the context of foreign minors, the application of geospatial and geomorphological methods can aid in identifying high-risk departure points, habitual movement patterns, and probable disappearance routes. These techniques, especially when combined with community reporting and digital mapping tools, could help authorities allocate resources more effectively—particularly in remote areas or institutional settings with recurrent disappearances [5,8,45,46,47]. To operationalize these tools, Italian institutions could initiate pilot training sessions involving law enforcement and geoscience units. Existing applications in Italy and internationally (e.g., [5,42,47,48]) show potential to scale these methods based on available resources.

4.3. Data Collection and Sharing

The limitations of the annual reports issued by the Italian Ministry of the Interior have been extensively discussed [6]. While more detailed than similar reports from other countries, they lack clarity and consistency. Several improvements are proposed:

- Introduce a legend and definitions: Each report should clearly define all categories to avoid ambiguity. For example, motivations for disappearance reported at the time of filing should be tracked to determine how often they are confirmed upon case resolution.

- Redefine ambiguous categories: The “voluntary disappearance” category, for instance, warrants reconsideration. A person leaving voluntarily is not necessarily “missing,” particularly in cases involving minors in unfamiliar environments or non-native speakers. Objective categorizations, such as the location of disappearance or the individual’s level of autonomy, could provide more useful insights. In addition, we propose a basic checklist for missing person reporting (Appendix C), which includes standard variables such as age brackets, gender, setting, and resolution time.

- Standardize reports: Frequent changes in leadership at the Office of the Special Commissioner for Missing Persons result in reports that vary in format and content. A standardized structure, mandated by higher authorities, would enhance comparability across years. A proposed structure includes the following:

- Introduction of new search techniques.

- Annual statistics on reports, missing persons, and recoveries, with detailed breakdowns by gender, age (in narrower ranges), and location.

- Average recovery times.

- Analysis of the most effective search methods.

- Staffing and resources allocated to searches.

- Specific studies, such as analyses of migrants or disappearances from institutions.

These changes would not only improve the utility of the reports for research and policy-making but also create a more transparent and systematic approach to addressing the phenomenon.

A systematic approach to the issue of missing persons in Italy requires better accessibility of resources, the integration of active search technologies, and significant improvements in data collection and sharing. Each missing person case must be treated with the same urgency, and the categorization of cases should be focused on supporting search and recovery efforts rather than labeling cases in ways that might unintentionally deprioritize them. Standardized and transparent reporting would allow for the identification of patterns and trends that could enhance future search efforts and preventative measures. While Italy’s fragmented institutional response is shaped by national limitations, it also reflects broader EU-wide tensions between migration control and child protection. The lack of shared data protocols and diverging national definitions of ‘missing’ hinder coordinated efforts, particularly for intra-EU mobility of minors.

This study is based solely on the reinterpretation of existing institutional data, which is itself inconsistent across time. The lack of individual-level records and the limited public availability of real-time data constrain the depth of analysis. Additionally, given the absence of centralized EU-wide missing minor databases, comparative insights remain contextual rather than fully systemic.

5. Conclusions

This study offers a socially grounded analysis of the persistent yet underestimated issue of missing foreign minors in Italy—an issue rarely acknowledged by public opinion and largely overlooked by the scientific community. Rather than presenting new experimental data, the article critically reexamines institutional reports and policy responses, highlighting systemic gaps and inconsistencies. It advocates for a shift in how such disappearances are framed, suggesting that forensic geospatial tools—such as locus operandi analysis and remote sensing—can complement broader socio-political reforms. The intent is to open a space for reflection and interdisciplinary dialog, bridging social concerns with emerging forensic perspectives.

The institutional attitude toward the issue of missing persons—and the corresponding message conveyed to the public—is one of superficiality and disinterest. This is exemplified by two striking images. The first is a meme featuring Leonardo DiCaprio from a Tarantino film, inexplicably and grotesquely included in an official report from the Ministry of the Interior (Figure 6). The second is the use of ATMs to display rotating images of missing persons, a method that reflects both outdated practices and a lack of systemic engagement [49].

Figure 6.

A controversial meme included in page 67 of the 2022 Annual Report by the Special Commissioner for Missing Persons (https://commissari.gov.it/media/1952/xxviii-relazione-anno-2022-commissario-straordinario-persone-scomparse.pdf, accessed on 23 November 2024). This image, drawn from popular cinema, raises concerns about the institutional tone adopted in official documentation, highlighting the gap between communication strategy and the gravity of the missing minors crisis.

These images encapsulate the broader institutional approach: a facade of responsibility in official communications, such as the heartfelt letters from families and quotes included in the opening pages of reports, contrasted with a lack of sustained attention. This superficial engagement mirrors the fleeting media coverage of missing persons, which only resurfaces during high-profile cases and quickly fades.

The ATM example, in particular, highlights systemic stagnation. While practical and widespread, the method pales in comparison to more effective systems like the AMBER Alert, which has proven impactful in other countries. Such outdated approaches symbolize the broader need for modernization in the methods and attitudes toward missing persons in Italy.

The integration of locus operandi analysis and spatial risk modeling into institutional protocols would allow for a shift from reactive search strategies to proactive monitoring, thereby enhancing both prevention and forensic documentation efforts. While forensic geoarchaeology importance has been recognized in crime prevention globally, it remains underutilized in Italy. Studies from countries such as Nigeria [50] and India [51] demonstrate how integrating geographic profiling into crime prevention and investigation can yield significant benefits.

In the specific case of missing foreign minors in Italy, certain locations, such as institutions and shelters, stand out as hotspots for disappearances. More precise data linking disappearances to specific locations could enable the application of existing technologies like geographic profiling and advanced geolocation methods. These tools could be tailored to track and recover missing minors more effectively, providing a preventative framework for future cases.

This study underscores the urgent need to elevate public and institutional awareness of the missing persons phenomenon, particularly foreign minors. The issue has been consistently undervalued, receiving attention only when tied to sensational crime stories before quickly disappearing from the public eye.

By integrating advanced technologies, refining data collection methods, and fostering a genuine institutional commitment, Italy could transform its approach to missing persons. It is hoped that this research, alongside others, will serve as a catalyst for meaningful change in how this critical issue is addressed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; methodology, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; software, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; validation, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; formal analysis, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; investigation, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; resources, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; data curation, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; writing—review and editing, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; visualization, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; supervision, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; project administration, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B.; funding acquisition, S.D.C., R.M.D.M. and P.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at the Italian Ministry of the Interior website (https://commissari.gov.it/persone-scomparse/attivita/relazioni-periodiche/tutte-le-relazioni-periodiche/, accessed on 23 November 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This table presents an annual scoring matrix showing how many unique data points each year’s report contained, with notes on what new types of information were introduced.

| Year | Total Unique Data Points | Notable New Elements |

| 2014 | 4 | First nationality breakdown |

| 2015 | 5 | Age–gender breakdown |

| 2016 | 6 | Phone reporting data |

| 2017 | 7 | Voluntary/involuntary distinction |

| 2018 | 6 | Regional breakdown by age |

| 2019 | 5 | Unknown categories added |

| 2020 | 8 | Age categories (0–11, 11–14, 15–17) |

| 2021 | 7 | Motivation data reintroduced |

| 2022 | 6 | Use of gauges and infographic elements |

| 2023 | 7 | MSNA institutional outcomes |

Appendix B

This table presents a glossary explaining key ambiguous categories such as “unknown” or “foreign nationals abroad.

| Term | Definition |

| Unknown | Case where nationality or age clearly recorded; often merged with ‘foreign nationals’ |

| Unknown location or state | Geographic status unknown at time of report; no specific national or regional classification |

| Migration-related | Disappearance linked to migratory routes, including loss at sea or informal entry points |

| Foreign nationals abroad | Non-Italian citizens reported missing while outside Italian territory; legal framework unclear |

Appendix C

This table presents a minimum reporting template listing essential information to be collected when a foreign minor goes missing.

| Category |

| Date of Disappearance |

| Age at Disappearance |

| Gender |

| Nationality |

| MSNA Status (Yes/No) |

| Location Last Seen |

| Reporting Party (e.g., guardian, institution, etc.) |

| Circumstances of Disappearance |

| Language Spoken |

| Medical/Psychological Notes |

| Search Methods Used |

| Recovery Outcome (Found/Missing/Deceased) |

| Time to Recovery (days) |

| Institutional Follow-Up |

References

- Testoni, I.; Franco, C.; Palazzo, L.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A.; Wieser, M.A. The Endless Grief in Waiting: A Qualitative Study of the Relationship between Ambiguous Loss and Anticipatory Mourning amongst the Relatives of Missing Persons in Italy. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campesi, G. Lo Statuto Della Detenzione Amministrativa Degli Stranieri. Una Prospettiva Teorico-Giuridica. Ragion Prat. 2014, 2, 471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Baraybar, J.P.; Caridi, I.; Stockwell, J. A Forensic Perspective on the New Disappeared. In Forensic Science and Humanitarian Action; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 101–115. ISBN 978-1-119-48206-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rassegna dell’Arma dei, C. L’esercito Silente. Strumenti e Tecniche d’intervento per La Ricerca Di Persone Scomparse. Rassegna DellArma Dei Carabinieiri 2023, 1, 5–52. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, P.M.; Di Maggio, R.M.; Mesturini, S. Forensic Geoarchaeology in the Search for Missing Persons. Forensic Sci. 2021, 1, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutte le Relazioni Periodiche del Commissario Straordinario. Available online: http://commissari.gov.it/persone-scomparse/attivita/relazioni-periodiche/tutte-le-relazioni-periodiche/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- James, M.; Anderson, J.; Putt, J. Missing Persons in Australia: Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice; Australian Institute of Criminology: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Congram, D. Missing Persons: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Disappeared; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-1-55130-930-9. [Google Scholar]

- Morewitz, S.J.; Colls, C.S. Handbook of Missing Persons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-40199-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Reyes, J.; Congram, D.; Sirbu, R.; Floridi, L. Where Are They? A Review of Statistical Techniques and Data Analysis to Support the Search for Missing Persons and the New Field of Data-Based Disappearance Analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 376, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller-Roazen, D. Absentees: On Variously Missing Persons; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-942130-48-2. [Google Scholar]

- LEGGE 14 Novembre 2012, n. 203-Normattiva. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2012-11-14;203 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Sbattella, F. Persone Scomparse. Aspetti Psicologici Dell’attesa e Della Ricerca, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-917-2731-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brandi, C. The Social Recognition of the Phenomenon of Missing Persons and the Italian Response from Institutions and the Third Sector. Riv. Psicol. DellEmergenza E DellAssistenza Um. 2012, 1, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldi, A.; Guarnieri, T. Percorsi Già Segnati e Strade da Decidere: Il Diritto Alla Cultura, Al Gioco, Allo Sport e Alla Scelta Del Proprio Futuro; TuttoMondo; Viaggio nel mondo dei minori stranieri non accompagnati: Un’analisi giuridicofattuale; Fondazione Basso: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti, M. Dubito, Ergo Iudico. Le modalità di accertamento dell’età dei minori stranieri non accompagnati in Italia. Diritto, Immigrazione e Cittadinanza 2022, 1, 172–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cameriere, R.; Scendoni, R.; Ferrante, L.; Mirtella, D.; Oncini, L.; Cingolani, M. An Effective Model for Estimating Age in Unaccompanied Minors under the Italian Legal System. Healthcare 2023, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubelaker, D.H.; Khosrowshahi, H. Estimation of Age in Forensic Anthropology: Historical Perspective and Recent Methodological Advances. Forensic Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penasa, S. L’accertamento dell’età dei minori stranieri non accompagnati: Quali garanzie? Un’analisi comparata e interdisciplinare. Federalismi 2019, 2, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Soliman, N.A.; Elalaily, R.; Di Maio, S.; Bedair, E.M.A.; Kassem, I.; Millimaggi, G. Pros and Cons for the Medical Age Assessments in Unaccompanied Minors: A Mini-Review. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2016, 87, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Burrai, J.; Pizzo, A.; Prisco, B.; De Filippis, L.; Mari, E.; Quaglieri, A.; Giannini, A.M.; Lausi, G. Missing Children in Italy from 2000 to 2020: A Review of the Phenomenon Reported by Newspapers. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Cammisa, I.; Zona, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, C.; Bali, D.; Pastore, M.; Vural, M.; Giardino, I.; Konstantinidis, G.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. The Growing Issue of Missing Children: The Need for a Comprehensive Strategy. J. Pediatr. 2024, 270, 114051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassinari, F. The Identification of Unaccompanied Foreign Minors and the Voluntary Guardian in Italy: An Example to Be Followed by the EU? Cuad. Derecho Transnacional 2019, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edkins, J. Missing: Persons and Politics; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8014-6279-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, T. Reporting and investigating missing persons: A background paper on how to frame the issue. Off. Justice Programs 2019, 255934, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Michalitsi-Psarrou, A.; Psarras, C.N.; Psarrasj, A. Collective Awareness Platform for Missing Children Investigation and Rescue. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on ICT, Society and Human Beings, Online, 21–23 July 2020; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- García-Barceló, N.; González Álvarez, J.L.; Woolnough, P.; Almond, L. Behavioural Themes in Spanish Missing Persons Cases: An Empirical Typology. J. Investig. Psychol. Offender Profiling 2020, 17, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommarribas, A. How Do EU Member States Treat Cases of Missing Unaccompanied Minors? Directorate General for Migration and Home Affairs, European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, X.M. Economic Crisis and Child Maltreatment in Spain: The Consequences of the Recession in the Child Protection System. J. Child. Serv. 2021, 16, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehal, N.; Mitchell, F.; Wade, J. Lost from View: Missing Persons in the UK; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-86134-491-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe, N.R.; Stevenson, O.; Woolnough, P. Missing Persons: The Processes and Challenges of Police Investigation. Polic. Soc. 2015, 25, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuta, A.; Sidebottom, A. Missing Children: On the Extent, Patterns, and Correlates of Repeat Disappearances by Young People. Polic. J. Policy Pract. 2020, 14, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, S.; Fusco-Maguire, A.; Bromley, C.; Conway, B.; Giles, S.; O’Brien, F.; Monaghan, P. Examining the Impact of Dedicated Missing Person Teams on the Multiagency Response to Missing Children. Camb. J. Evid.-Based Polic. 2023, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Daum, C.; Neubauer, N.; Cruz, A.M.; Rincón, A.R. Technology for Independence in Mobility in the Community. In Autonomy and Independence: Aging in an Era of Technology; Liu, L., Daum, C., Neubauer, N., Cruz, A.M., Rincón, A.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 135–141. ISBN 978-3-031-03764-1. [Google Scholar]

- Düvell, F.; Denaro, C. Maritime Migration and Maritime Rescue in the Central Mediterranean: Perspectives of Key Actors; DeZIM Policy Papers, German Centre for Integraton and Migraton Research (DeZIM): Berlin, Germany, 2024; ISBN 978-3-948289-83-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris, V. Dalla tratta al traffico, allo sfruttamento: I minori stranieri coinvolti nell’accattonaggio, nelle economie illegali e nella prostituzione. In Evoluzione del fenomeno ed ambiti di sfruttamento; Carchedi, F., Orfano, I., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Rome, Italy, 2007; pp. 216–276. ISBN 978-8-846-49184-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gjergji, I. L’asilo dei minori. Accoglienza, trattamento e condizione sociale dei minori richiedenti asilo in Italia. DEP 2017, 34, 80–98. [Google Scholar]

- Truenumbers Cosa Succede su Internet in Europa Ogni Giorno: Spedite 20 Miliardi di Mail. Available online: https://www.truenumbers.it/internet-europa/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Sleigh-Johnson, P.; Gabbert, F.; Scott, A. An Exploration into Why There Is an Overrepresentation of BAME People in Missing Person Cases. Int. J. Missing Pers. 2024, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, S.A.; Hanefeld, J.; Corte-Real, A.; da Cunha, P.R.; de Gruchy, T.; Manji, K.N.; Netto, G.; Nunes, T.; Şanlıer, İ.; Takian, A.; et al. Digital Solutions for Migrant and Refugee Health: A Framework for Analysis and Action. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2025, 50, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklavou, K.; Venieraki, M.; Balikou, P. Missing Children: A General Overview. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. Ment. Health 2024, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.M.; Di Maggio, R.M.; Mesturini, S. Materials for the Study of the Locus Operandi in the Search for Missing Persons in Italy. Forensic Sci. Res. 2022, 7, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Luo, P.; Yao, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, K.; Guan, Q. Predicting the Locations of Missing Persons in China by Using NGO Data and Deep Learning Techniques. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2304076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, H.; Fyfe, n. Missing Geographies. ResearchGate 2012, 37, 615–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.M.; Di Maggio, R.M.; Mesturini, S. A Complementary Remote-Sensing Method to Find Persons Missing in Water: Two Case Studies. Forensic Sci. 2023, 3, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensieri, M.G.; Garau, M.; Barone, P.M. Drones as an Integral Part of Remote Sensing Technologies to Help Missing People. Drones 2020, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Christiaans, H.; Cho, J. Enhancing Missing Persons Search Strategies through Technological Touchpoints. Polic. Soc. 2024, 34, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffell, A.; Mckinley, J.; Donnelly, L.; Harrison, M.; Keaney, A. Geoforensics, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-05735-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, N.; Press Release—Euronet Worldwide Inc. Diffonde gli Avvisi dei Minori Scomparsi Sugli Schermi Dei Propri ATM Grazie all’Accordo Con il Commissario Straordinario del Governo Italiano Per le Persone Scomparse. Available online: https://www.euronetatms.it/press-release-euronet-worldwide-inc-diffonde-gli-avvisi-dei-minori-scomparsi-sugli-schermi-dei-propri-atm-grazie-allaccordo-con-il-commissario-straordinario-del-governo-italiano-per-le-per/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Bello, I.E.; Ikhuoria, I.A.; Agbaje, I.; Ogedegbe, S.O. Managing Urban Crimes with Geoinformatics: A Case Study of Benin City, Nigeria. Comput. Eng. Intell. Syst. 2013, 4, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraju Lokanath, S.; Kishor, K.; Thulasi, R.B. Crime Mapping and Analysis Using Geospatial Techniques-A Study of Shivamogga City in Karnataka State, India. Res. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 7, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).