Atterberg Limits and Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Oil Sands Mining

1.2. Atterberg Limits of Oil Sands Tailings

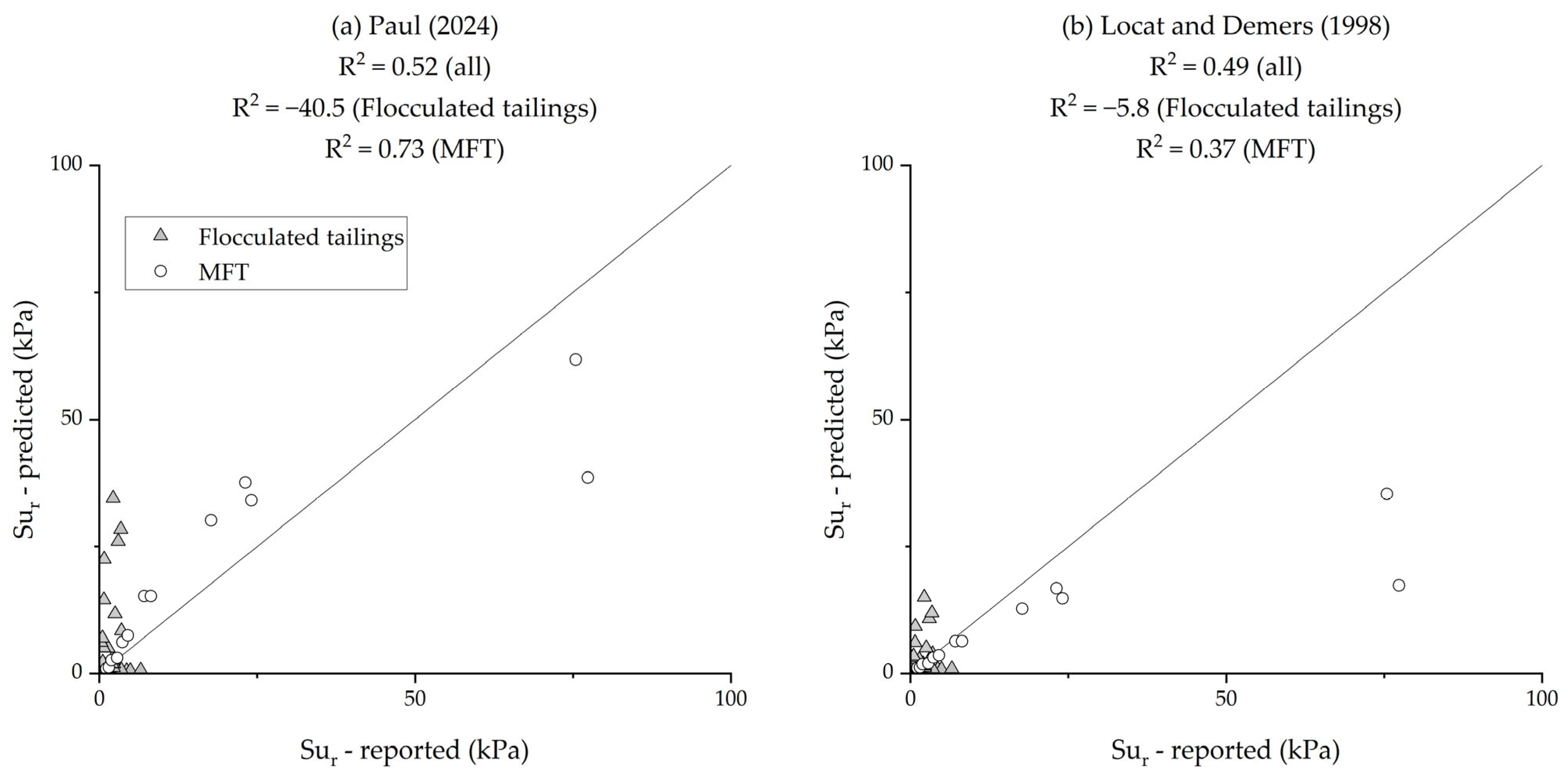

1.3. Limitations of Existing Relationships Between Remoulded Undrained Shear Strength and Liquidity Index

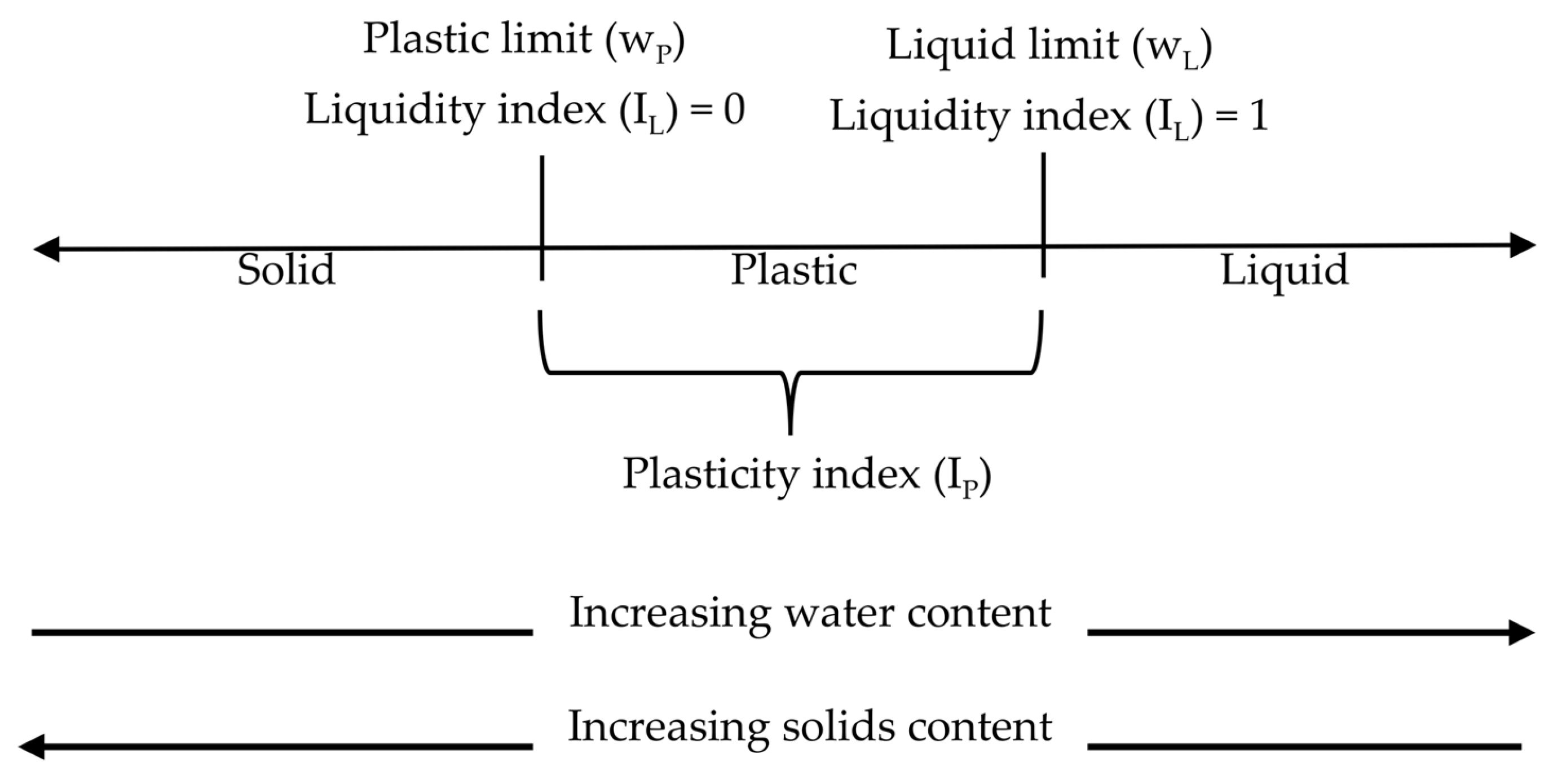

1.4. Background on Atterberg Limits

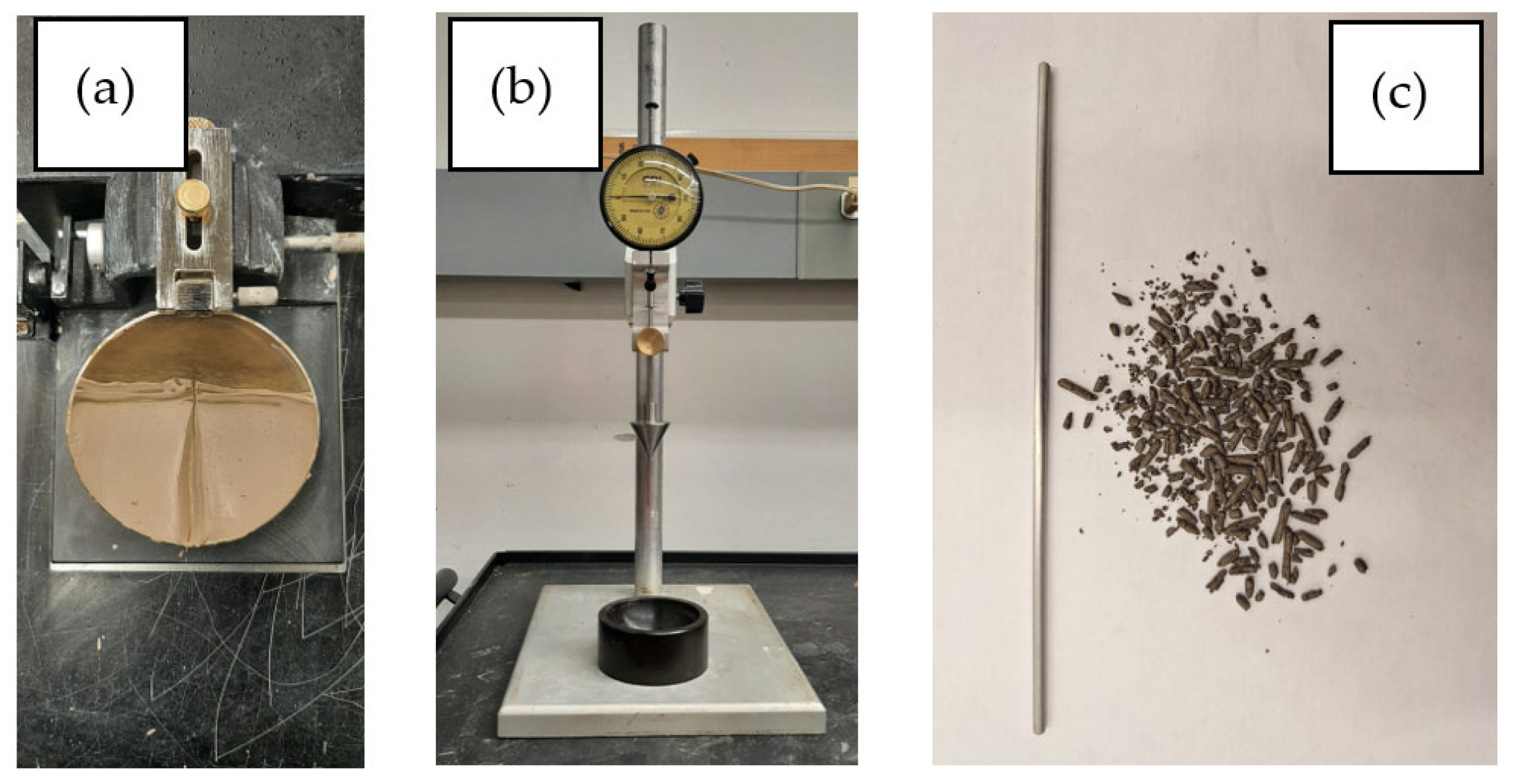

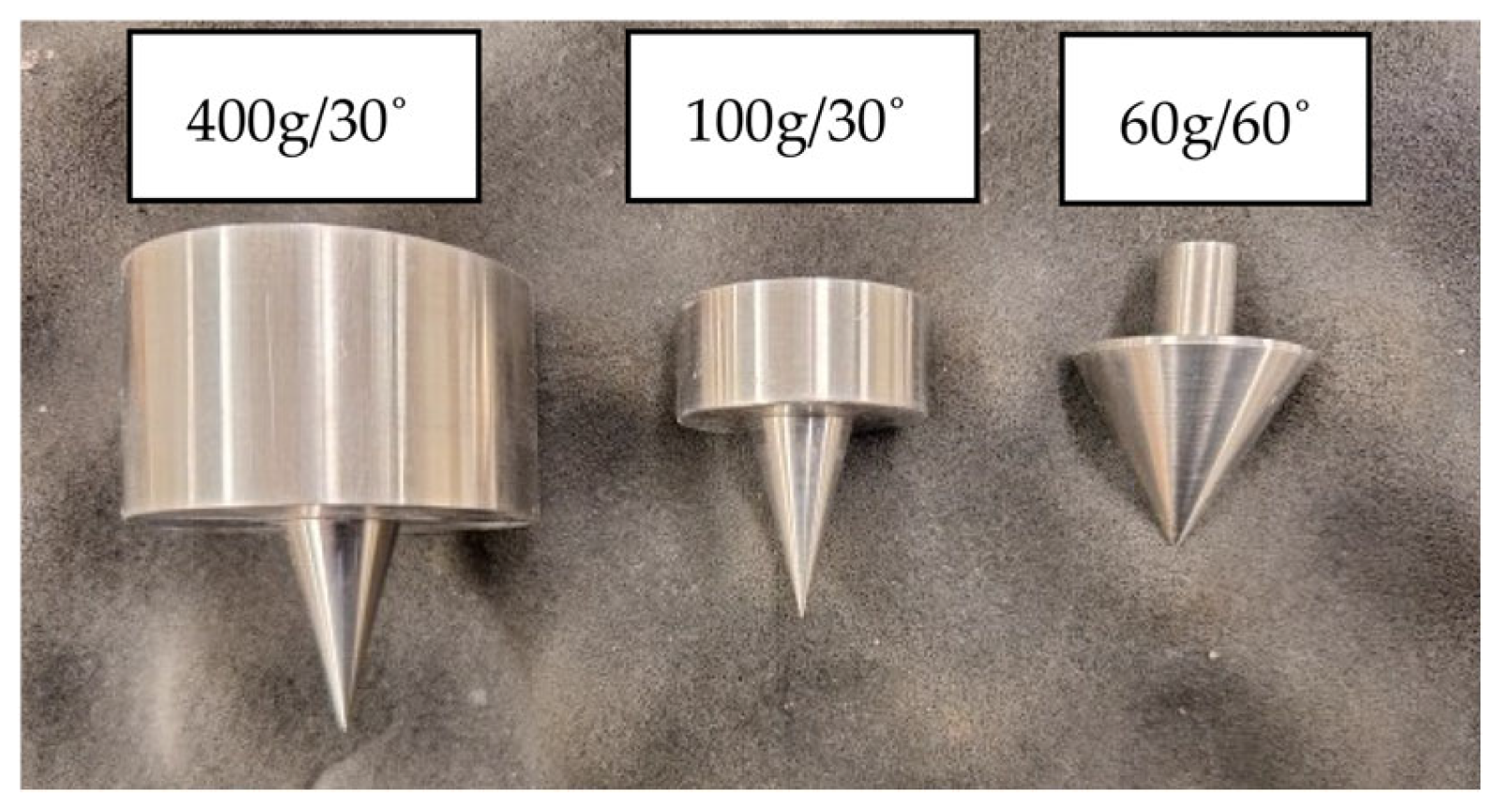

1.4.1. Methods for Measuring Atterberg Limits

1.4.2. Influence of Various Factors on the Atterberg Limits of Oil Sands Tailings and Natural Soils

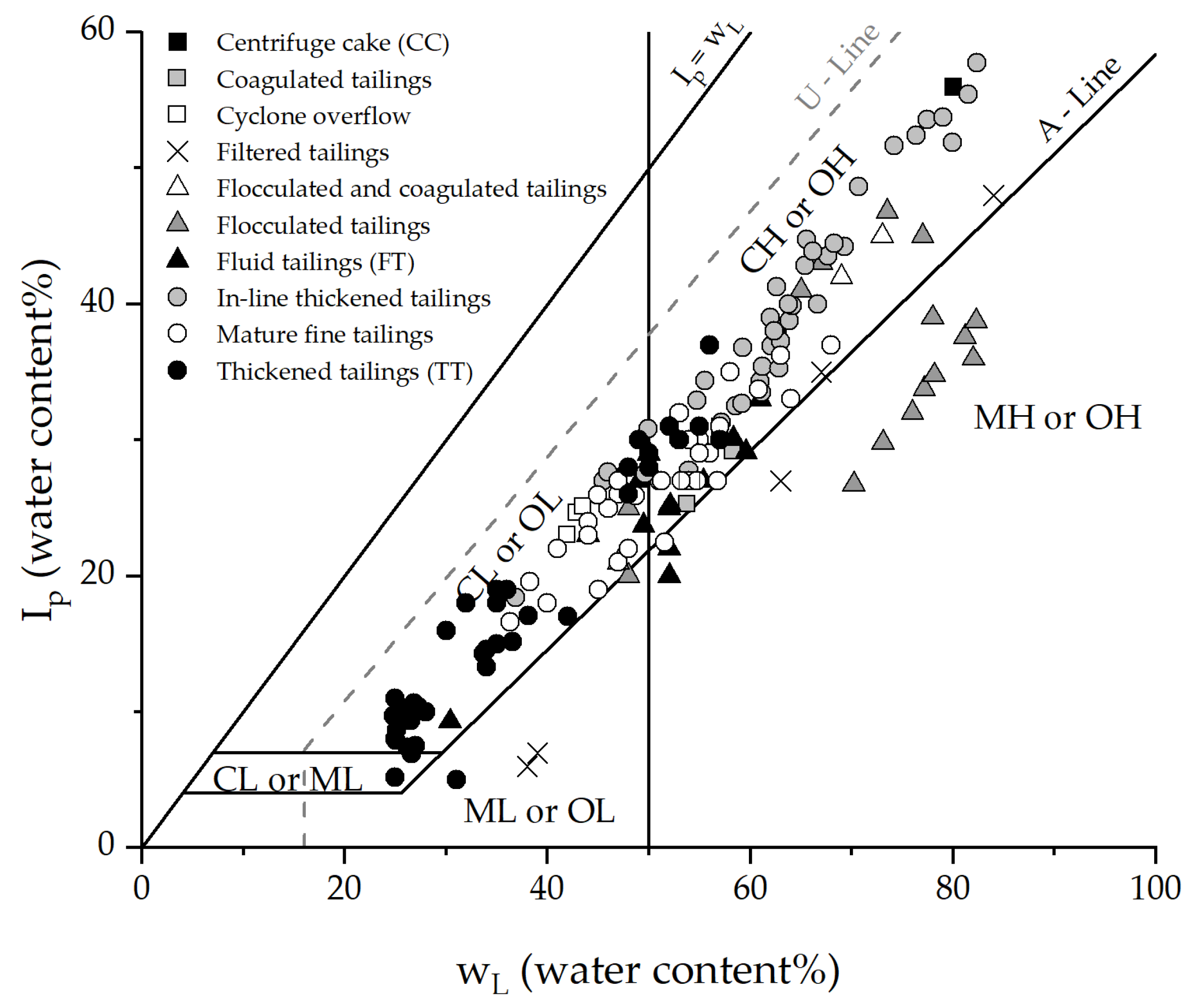

1.4.3. Review of Published Atterberg Limits of Oil Sands Tailings

2. Material Characterization and Methodology

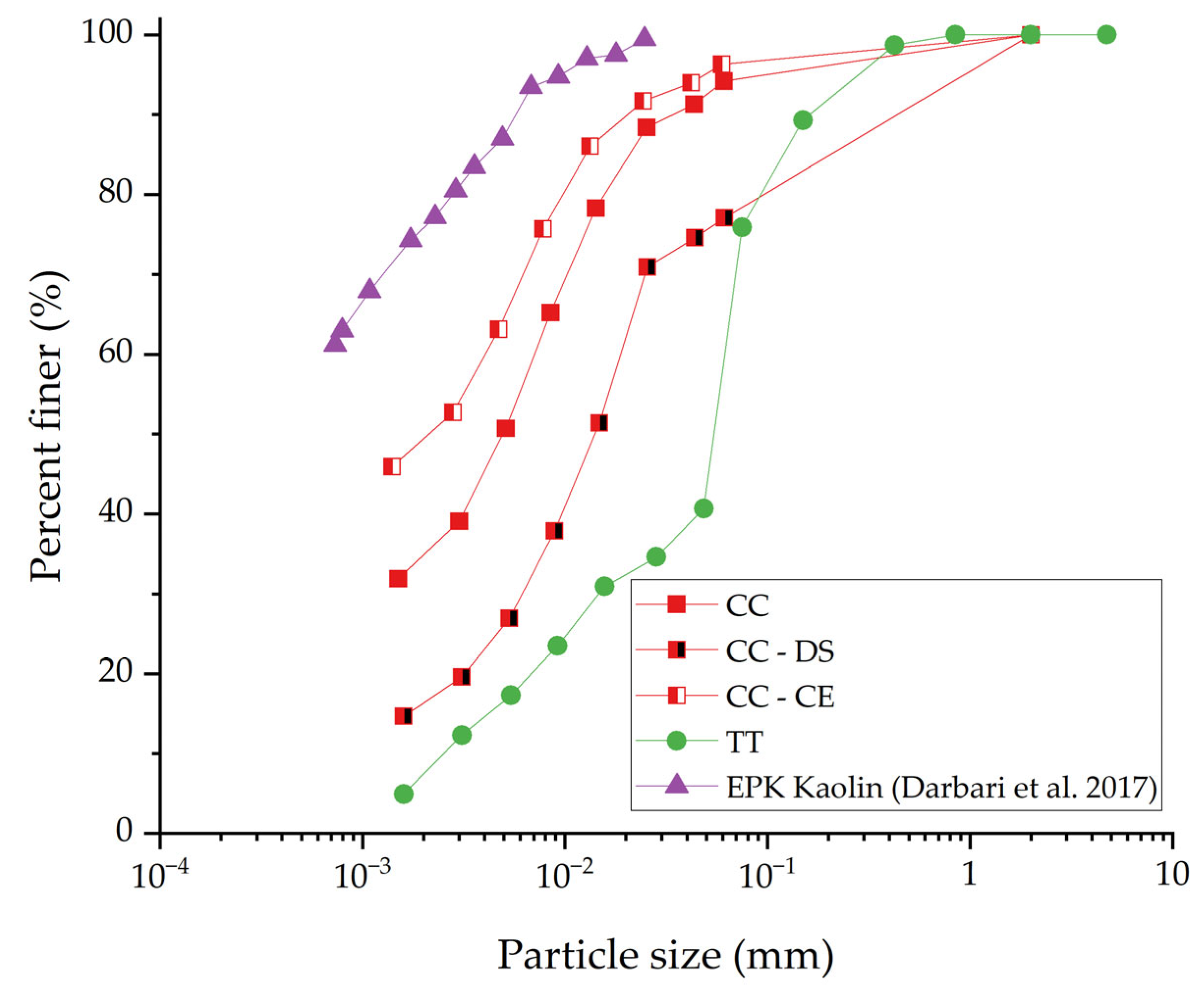

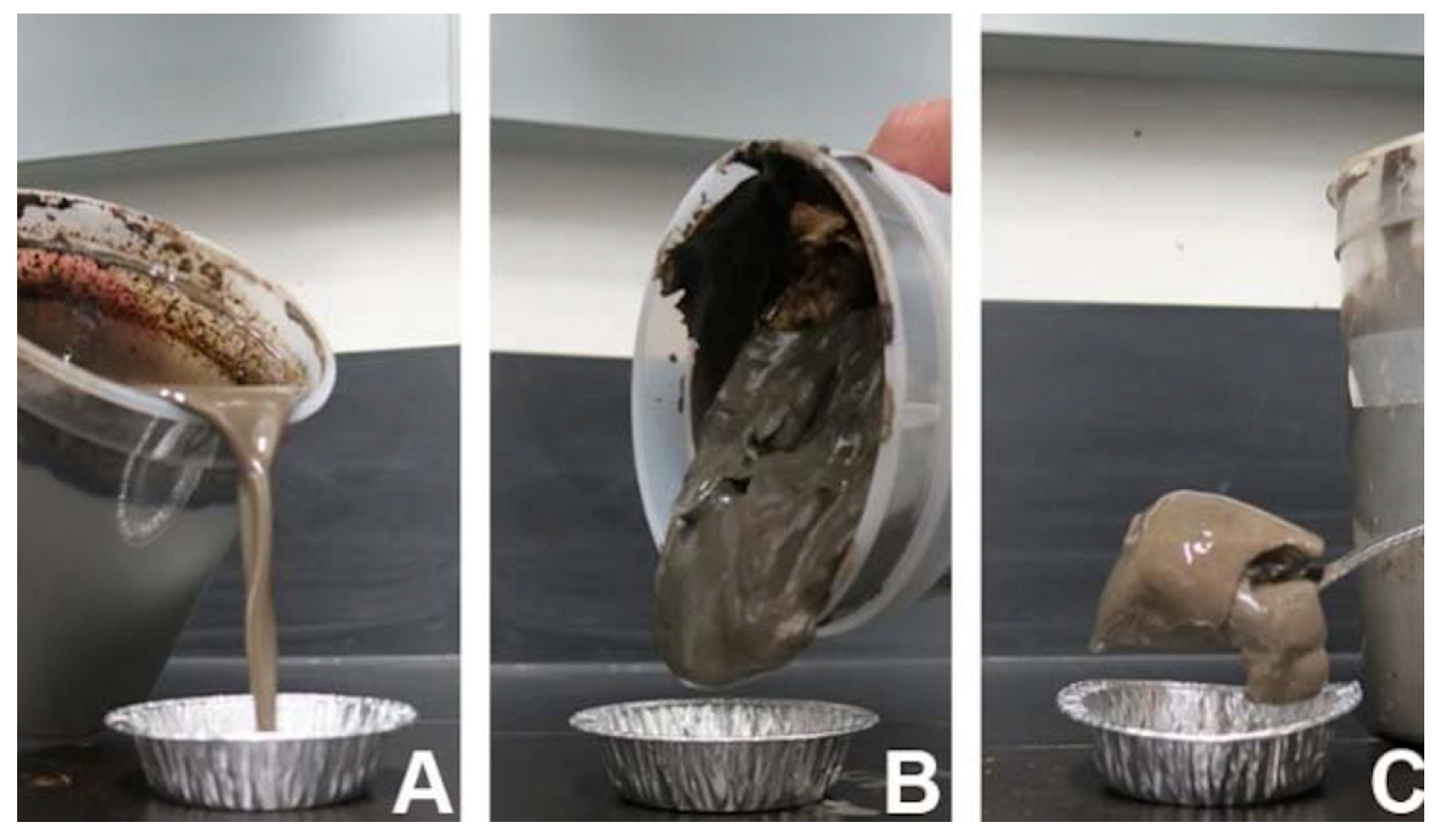

2.1. Test Materials

2.2. Atterberg Limits

2.3. Developing a Relationship Between Remoulded Undrained Shear Strength and Liquidity Index

2.4. Summary of Laboratory Test Program

- Casagrande cup and fall cone—effect of test method on wL.

- Drying and rewetting—effect of diluting pore water chemistry on Atterberg limits and strength behaviour.

- CE- and DS-amendment—effect of major physical and chemical changes of sample properties (e.g., removal of bitumen, removal of pore water, drying at high temperatures) on Atterberg limits and strength behaviour.

| Sample | CC | TT | FT | EPK Kaolin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR * | DS | CE | AR | DS | CE | AR | DS | CE | |||

| Characterization | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Atterberg limits | |||||||||||

| Dried | wL—FC † | X | X | X | |||||||

| wL—C ‡ | X | X | X | ||||||||

| wP | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rewetted | wL—FC † | X | X | X | |||||||

| wP | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rehydrated | wL—FC † | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| wL—C ‡ | X | ||||||||||

| wP | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sur vs. IL | |||||||||||

| Dried | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rewetted | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rehydrated | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

3. Results

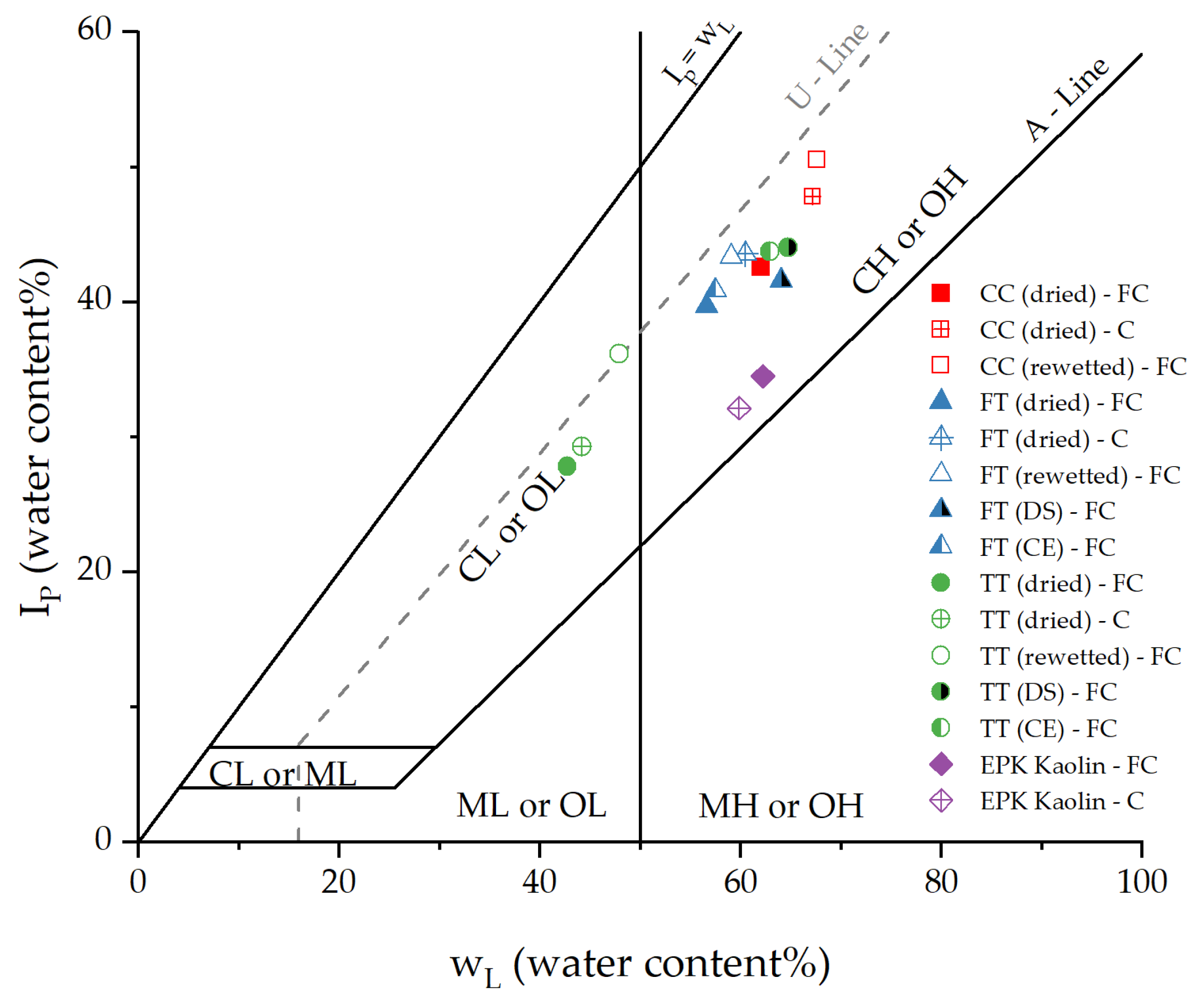

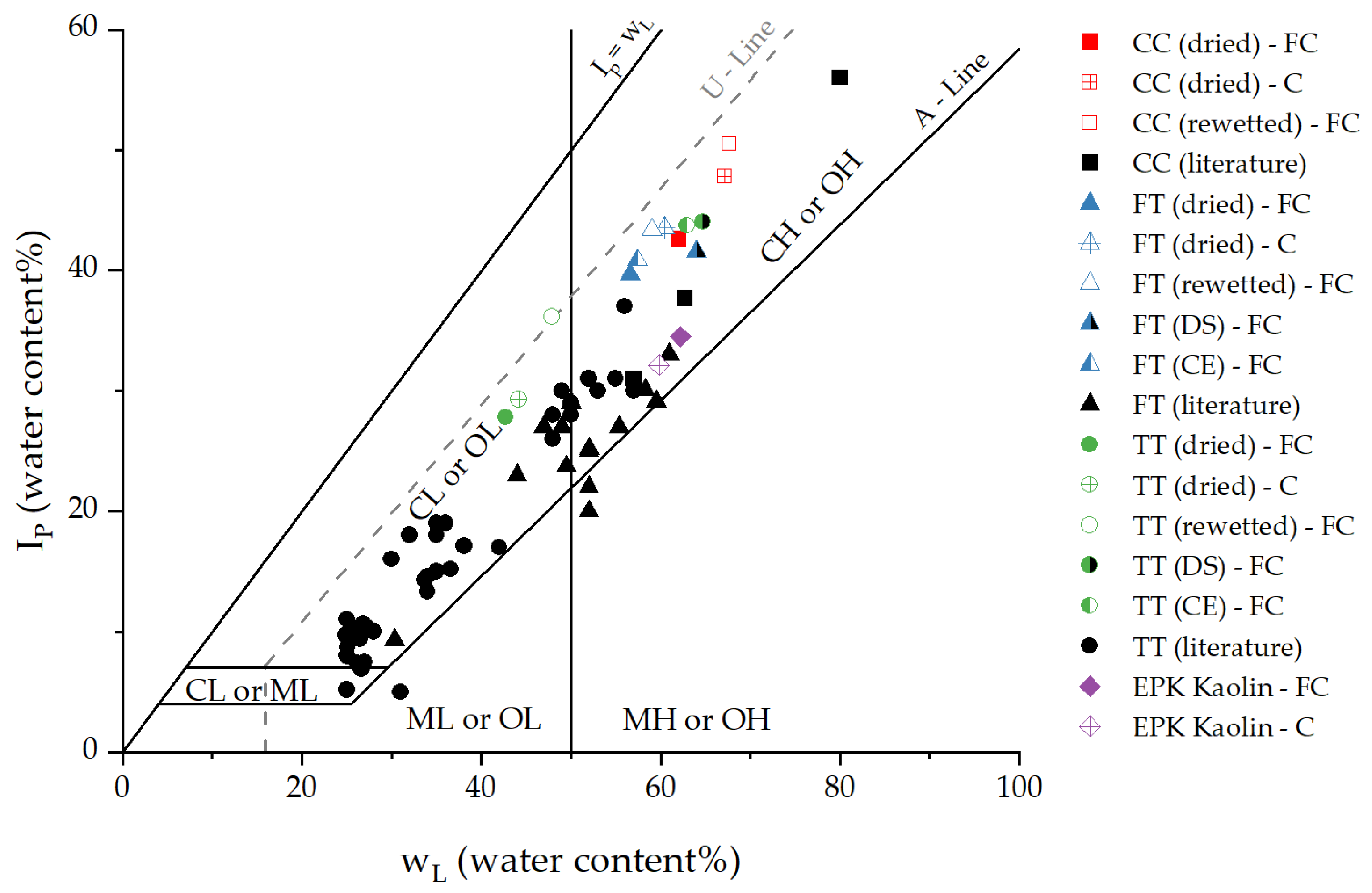

3.1. Measured Atterberg Limits of All Samples

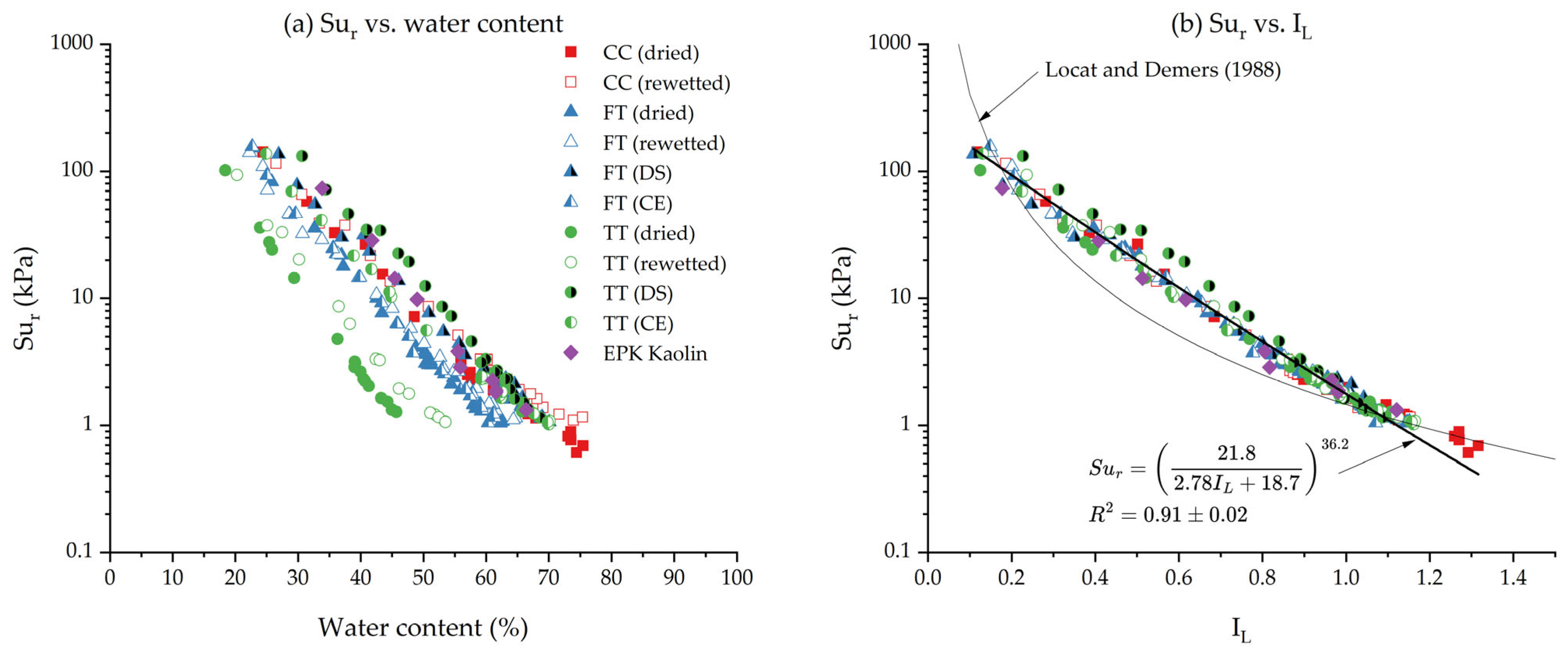

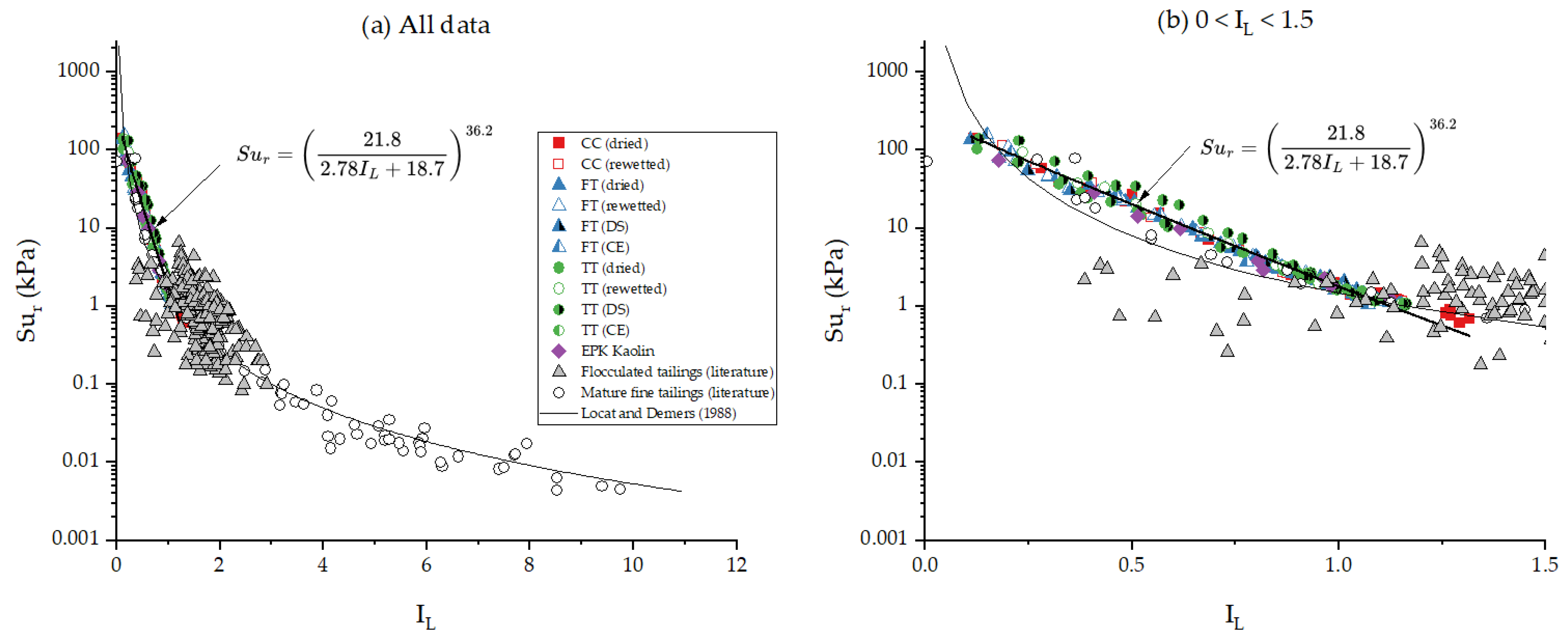

3.2. Proposed Relationship Between Remoulded Undrained Shear Strength and Liquidity Index

4. Discussion

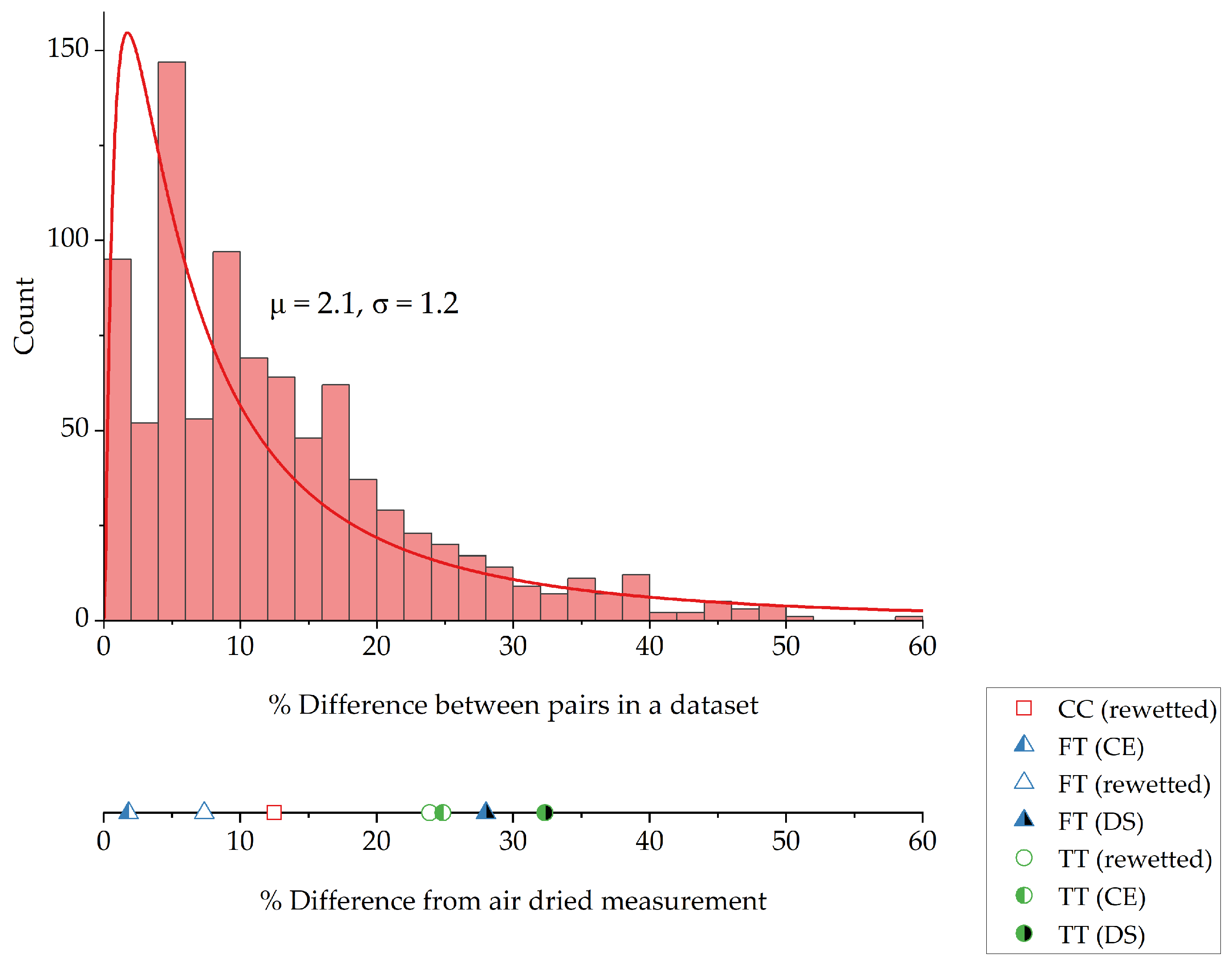

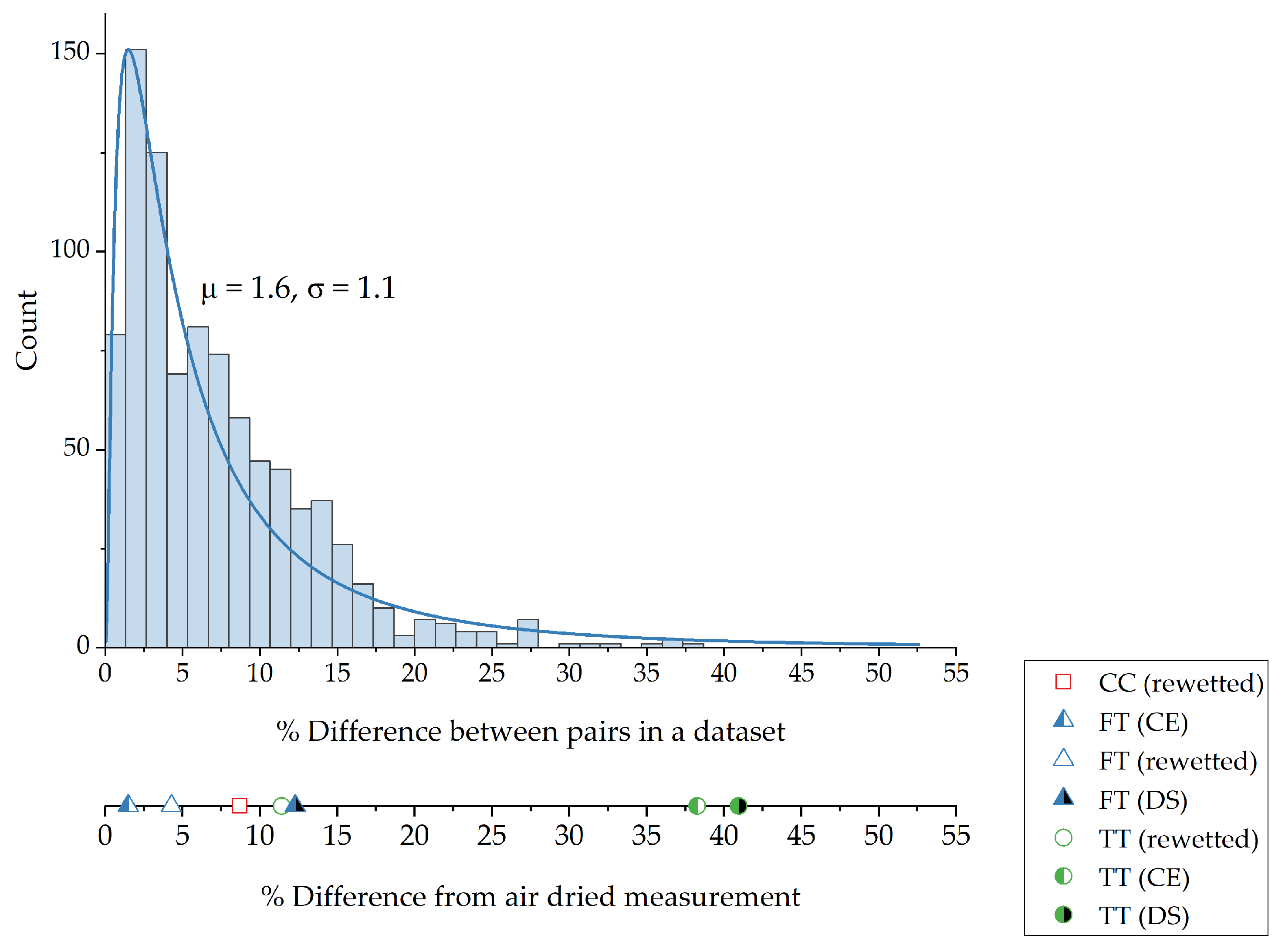

4.1. Variability of Atterberg Limits

4.2. Comparison of Proposed Relationship Between Remoulded Undrained Shear Strength and Liquidity Index to Locat and Demers Relationship

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Ruture Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Tailings Type | Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Centrifuge cake | Chigbo et al. (2021) [58], Schafer (2018) [59], Smith et al. (2018) [60], Stienwand (2021) [61] |

| MFT | Bajwa (2015) [21], Banas (1991) [17], Chappel and Blond (2013) [62], Gholami (2014) [63], Guo and Shang (2014) [64], Jeeravipoolvarn (2005) [65], Masala and Matthews (2010) [66], Nik (2013) [67], Pollock (1988) [68], Rima (2022) [69], Rozina (2013) [70], Scott et al. (2013) [32], Shobrook (2014) [71], Sorta (2015) [41], Tang (1997) [45], Torghabeh (2013) [72], Yao (2016) [44], Yao et al. (2016) [73], Zhang (2012) [74] |

| Flocculated tailings | Amoako (2020) [75], Bajwa (2015) [21], Gholami (2014) [63], Jeeravipoolvarn et al. (2020) [20], Rozina (2013) [70] |

| Coagulated tailings | Miller et al. (2010) [40] |

| Flocculated and coagulated tailings | Elias (2019) [76] |

| Thickened tailings | Innocent-Bernard (2013) [43], Jeeravipoolvarn et al. (2008) [42], Kabwe et al. (2019) [35], Kabwe et al. (2021) [36], Masala and Matthews (2010) [66], Masala et al. (2014) [77], Sorta (2015) [41], Wijermars (2011) [78], Wilson et al. (2018) [38], Yao (2016) [73], Yao et al. (2012) [79], Yao et al. (2016) [73], Yuan and Lahaie (2009) [54] |

| Cyclone overflow | Jeeravipoolvarn (2010) [34], Sorta (2015) [41] |

| In-line thickened tailings | Jeeravipoolvarn (2010) [34], Kabwe et al. (2013) [37], Rima (2022) [69] |

| Filtered tailings | Ansah-Sam et al. (2021) [80] |

| Untreated FT | Amoako (2020) [75], Contreras et al. (2015) [81], Elias (2019) [76], Jeeravipoolvarn et al. (2008) [42], Kabwe et al. (2021) [36], Miller et al. (2010) [40], Salam (2020) [82], Stienwand (2021) [61], Suthaker (1995) [83], Wilson et al. (2018) [38] |

Appendix B

| Sample | <44 µm (%) | SFR | Bitumen (wt%) | MBI (meq/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 91.4 | 0.1 | 1.53 | 13.6 |

| CC-DS | 74.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 11.5 |

| CC-CE | 94.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 11.9 |

| FT | 82.0 | 0.2 | 1.20 | 8.3 |

| TT | 39.3 | 1.5 | 1.29 | 8.9 |

| EPK Kaolin | 85.7 [51] | 0.2 | 0 | 3.7 [84] |

| Sample | Ion Concentrations (mg/L) | SAR | Conductivity (µS/cm) | pH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Cl− | HCO3− | SO42− | CO32− | ||||

| CC | 388 | 30.5 | 90.6 | 48.4 | 123 | 250 | 705.7 | 12 | 8.2 | 2390 | 8.4 |

| FT | 321 | 20.0 | 31.6 | 23.1 | 124 | 390 | 279.1 | 28 | 10.6 | 1540 | 8.6 |

| TT | 256 | 23.3 | 70.5 | 35.9 | 12.4 | 300 | 403.4 | 33 | 6.2 | 1520 | 8.6 |

| Oxide (wt%) | CC | FT | TT | Mineral Phase (wt%) | CC | FT | TT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | Quartz | 30.7 | 30.7 | 37.9 |

| MgO | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | K-Feldspars | 6.5 | 6.0 | 6.1 |

| Al2O3 | 24.6 | 25.2 | 24.2 | Siderite | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| SiO2 | 67.4 | 67.4 | 67.4 | Anatase | 0.8 | - | 0.8 |

| K2O | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.6 | Kaolinite | 46.4 | 41.0 | 40.7 |

| CaO | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | Mica/Illite | 13.6 | 20.0 | 13.3 |

| TiO2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | ||||

| Fe2O3 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

References

- BGC Engineering Inc. Oil Sands Tailings Technology Review; Oil Sands Research and Information Network, University of Alberta, School of Energy and the Environment: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chalaturnyk, R.J.; Scott, J.D.; Özüm, B. MANAGEMENT OF OIL SANDS TAILINGS. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2002, 20, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA). Technical Guide for Fluid Tailings Management; COSIA and Oil Sands Tailings Consortium: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA). Deep Deposit Design Guide for Oil Sands Tailings; COSIA: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, G.; Mooder, B.; Burton, B.; Jamieson, A. Shear Strength and Density of Oil Sands Fine Tailings for Reclamation to a Boreal Forest Landscape. In Proceedings of the 5th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Lake Louise, AB, Canada, 4–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Energy Regulator (AER). Directive 085: Fluid Tailings Management for Oil Sands Mining Projects. 2017. Available online: https://static.aer.ca/prd/documents/directives/Directive085.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Hyndman, A.; Sobkowicz, J. Oil Sands Tailings: Reclamation Goals & the State of Technology. In Proceedings of the 63rd Canadian Geotechnical Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 12–15 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Beier, N.A.; Kaminsky, H. Evaluating Consolidation Behaviors in High Water Content Oil Sands Tailings Using a Centrifuge. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossey, H.L.; Batycky, A.E.; Kaminsky, H.; Ulrich, A.C. Geochemical Stability of Oil Sands Tailings in Mine Closure Landforms. Minerals 2021, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, H.A.W.; Etsell, T.H.; Ivey, D.G.; Omotoso, O. Distribution of clay minerals in the process streams produced by the extraction of bitumen from Athabasca oil sands. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 87, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.L. Assessing the Strength and Bearing Capacity of Tailings for Oil Sands Reclamation. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sobkowicz, J.C.; Morgenstern, N.R. Reclamation and Closure of an Oil Sand Tailings Facility. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 5–8 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wroth, C.P.; Wood, D.M. The correlation of index properties with some basic engineering properties of soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1978, 15, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimobe, S.; Spagnoli, G. Relationships between undrained shear strength, liquidity index, and water content ratio of clays. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 4817–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Bora, P.K. Plastic Limit, Liquid Limit and Undrained Shear Strength of Soil—Reappraisal. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2003, 129, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.K.; Soga, K. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Banas, L.C. Thixotropic Behaviour of Oil Sands Tailings Sludge. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, N.; Wilson, W.; Dunmola, A.; Sego, D. Impact of flocculation-based dewatering on the shear strength of oil sands fine tailings. Can. Geotech. J. 2013, 50, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locat, J.; Demers, D. Viscosity, yield stress, remolded strength, and liquidity index relationships for sensitive clays. Can. Geotech. J. 1988, 25, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeravipoolvarn, S.; Wu, E.J.; Proskin, S.A.; Junaid, A.; Freeman, G. Field Water Release and Consolidation Performance of XUR Treated Fluid Fine Tailings. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 15–18 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa, T.M. Microstructure and Macroscopic Behaviour of Polymer Amended Oil Sands Mature Fine Tailings. PhD Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.L.; Beier, N.A. A Review of Atterberg Limits and Remoulded Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings. In Proceedings of the 77th International Canadian Geotechnical Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.L.; Beier, N.A. Assessing the Strength and Bearing Capacity of Tailings for Oil Sands Reclamation-A Summary. In Proceedings of the 8th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 9–10 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D4318-17; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- CAN/BNQ 2501-090; Determination of Liquid Limit by the Casagrande Apparatus and Determination of Plastic Limit. Bureau de Normalisation Du Québec (BNQ): Québec City, QC, Canada, 2019.

- Claveau-Mallet, D.; Duhaime, F.; Chapuis, R.P. Characterisation of Champlain Saline Clay from Lachenaie Using the Swedish Fall Cone. In Proceedings of the 63rd Canadian Geotechnical Conference Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 12–15 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, H.B.; Woodward, R.J.; Lundgren, R. Fundamental Aspects of the Atterberg Limits. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1964, 90, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skempton, A.W.; Northey, R.D. The Sensitivity of Clays. Géotechnique 1952, 3, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.K.; Thornburn, T.M. Study of the Reproducibility of Atterberg Limits; Highway Research Board of the Division of Engineering and Industrial Research: Washington, DC, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Basma, A.; Alhomoud, A.; Altabari, E. Effects of methods of drying on the engineering behavior of clays. Appl. Clay Sci. 1994, 9, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Dusseault, M.B.; Carrier, W.D. Behaviour of the clay/bitumen/water sludge system from oil sands extraction plants. Appl. Clay Sci. 1985, 1, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Kabwe, L.K.; Wilson, G.W.; Sorta, A.; Jeeravipoolvarn, S. Properties Which Affect the Consolidation Behaviour of Mature Fine Tailings. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Banff, AB, Canada, 3–6 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gidley, I.; Moore, T. Impact of Test Methodology on the Atterberg Limits of Mature Fine Tailings (slide deck). Presented at the Canadian Oil Sands Network for Research and Development Oil Sands Clay Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 20–21 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jeeravipoolvarn, S. Geotechnical Behavior of In-Line Thickened Oil Sands Tailings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kabwe, L.K.; Abdulnabi, A.; Wilson, G.W.; Beier, N.A.; Scott, J.D. Geotechnical and Unsaturated Properties of Metal Mines and Oil Sands Tailings. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–20 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kabwe, L.; Wilson, G.W.; Beier, N.A.; Barsi, D. Effect of Sand and Flyash on Unsaturated Soil Properties and Drying Rate of Oil Sands Tailings. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 7–10 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kabwe, L.; Wilson, G.W.; Donahue, R. Determination of Geotechnical Properties of In-Line Flocculated Fine Fluid Tailings for Oil Sands Reclamation. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Banff, AB, Canada, 3–6 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.W.; Kabwe, L.K.; Beier, N.A.; Scott, J.D. Effect of various treatments on consolidation of oil sands fluid fine tailings. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, M.; Leikam, J.; Fox, J. Romaniuk Use of Calcium Hydroxide as a Coagulant to Improve Oil Sands Tailings Treatment. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Banff, AB, Canada, 5–8 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.G.; Scott, J.D.; Sego, D.C. Influence of the Extraction Process on the Characteristics of Oil Sands Fine Tailings. CIM J. 2010, 1, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sorta, A.R. Centrifugal Modelling of Oil Sands Tailings Consolidation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jeeravipoolvarn, S.; Scott, J.D.; Donahue, R.; Ozum, B. Characterization of Oil Sands Thickened Tailings. In Proceedings of the 1st International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 7–10 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Innocent-Bernard, T. Evaporation, Cracking, and Salinity in a Thickened Oil Sands Tailings. Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. Dewatering Behaviour of Fine Oil Sands Tailings-An Experimental Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J. Fundamental Behaviour of Composite Tailings. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA). Guidelines for Performance Management of Oil Sands Fluid Fine Tailings Deposits to Meet Closure Commitments; COSIA: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, P.S.; Kaminsky, H. Slurry to Soil Clay Behaviour Model-Using Methylene Blue to Cross the Process/Geotechnical Engineering Divide. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T.; Beier, N. Preliminary Evaluation of Speswhite Kaolin as a Physical Analogue Material for Unsaturated Oil Sands Tailings. In Proceedings of the 76th Canadian Geotechnical Conference, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 1–4 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar Minerals Inc. Safety Data Sheet-EPK Kaolin; Laguna Clay Company: City of Industry, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA). Unified Fines Method for Minus 44 Micron Material and for Particle Size Distribution; COSIA: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Darbari, Z.; Jaradat, K.A.; Abdelaziz, S.L. Heating–freezing effects on the pore size distribution of a kaolinite clay. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansbo, S. A New Approach to the Determination of the Shear Strength of Clay by the Fall-Cone Test. Swedish Geotech. Inst. 1957, 14, 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Origin, Version 2023b; OriginLab Corporation: Northamption, MA, USA, 2023.

- Yuan, S.; Lahaie, R. Thickened Tailings (Paste) Technology and Its Applicability in Oil Sand Tailings Management. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Banff, AB, Canada, 1–4 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stianson, J.; Mahood, R.; Fredlund, D.G.; Sun, J. Large-Strain Consolidation Modeling to Determine Representative Tailings Consolidation Properties from Two Meso-Scale Column Tests. In Proceedings of the 5th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Lake Louise, AB, Canada, 4–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J.T. Geotechnical Engineering Reliability: How Well Do We Know What We Are Doing? J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2004, 130, 985–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, K.-K.; Kulhawy, F.H. Characterization of Geotechnical Variability. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbo, C.; Schoonmaker, A.; Xu, B.; Walton-Sather, K.; Kaminsky, H.; Collins, V.; Sun, S.; de Lucas Pardo, M.; van Rees, F. Case Study Assessment of Examining Wholistic Effects of Deploying Worms and Plants into Oil Sands Tailings. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 7–10 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, H. Freezing Characteristics of Mine Waste Tailings and Their Relation to Unsaturated Soil Properties. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.; Olauson, E.; Seto, J.; Schoonmaker, A.; Nik, R.M.; Freeman, G.; McKenna, G. Evaluation of Strength Enhancement and Dewatering Technologies for a Soft Oil Sands Tailings Deposit. In Proceedings of the 6th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 9–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stienwand, K.A. Accelerating Polymer Degradation to Explore Potential Long Term Geotechnical Behaviour of Oil Sands Fine Tailings. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chappel, M.J.; Blond, E. The Compatibility of Geotextiles with Mature Fine Tailings. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Banff, AB, Canada, 3–6 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, M. Shear Behaviour of Oil Sand Fine Tailings in Simple Shear and Triaxial Devices. Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Shang, J.Q. A Study on Electrokinetic Dewatering of Oil Sands Tailings. Environ. Geotech. 2014, 1, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeravipoolvarn, S. Compression Behaviour of Thixotropic Oil Sands Tailings. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masala, S.; Matthews, J. Predicting Development of Undrained Shear Strength in Soft Oil Sand Tailings. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 5–8 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nik, R.M. Application of Dewatering Technologies in Production of Robust Non-Segregating Tailings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, G.W. Large Strain Consolidation of Oil Sand Tailings Sludge. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rima, U.S. Effects of Seasonal Weathering on Dewatering of Polymer Amended Tailings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rozina, E. Bearing Capacity of Multilayer-Deposited In-Line Flocculated Oil Sands Tailings. Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shobrook, C. High Speed Dewatering of Fluid Fine Tailings. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Keystone, CO, USA, 5–8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Torghabeh, E.A. Stabilization of Oil Sands Tailings Using Vacuum Consolidation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; van Tol, A.F.; van Passen, L.; Vardon, P.J. Dewatering Behavior of Fine Oil Sands Tailings: A Summary of Laboratory Results. In Proceedings of the 5th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Lake Louise, AB, Canada, 4–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Laboratory Study of Freeze-Thaw Dewatering of Albian Mature Fine Tailings (MFT). MSc Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Amoako, K.A. Geotechnical Behaviour of Two Novel Polymer Treatments of Oil Sands Fine Tailings. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, J.A. Measurement of Floc Size and the Influence of Size Distribution on Geotechnical Properties of Oil Sands Fluid Fine Tailings. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Masala, S.; Nik, R.M.; Freeman, G.; Mahood, R. Geotechnical Insights into Deposition, Dewatering and Strength Performance of Thickened and Paste Tailings Deposits at Shell Canada’s Tailings Test Facility. In Proceedings of the 4th International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Lake Louise, AB, Canada, 7–10 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wijermars, E.A.M. Sedimentation of Oil Sands Tailings. Bachelor’s Thesis, Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; van Tol, F.; van Passen, L. Aspects of the Behavior of Fine Oil Sands Tailings during Atmospheric Drying. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Keystone, CO, USA, 5–8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ansah-Sam, M.; Davison, E.; Skinner, B. Filter Press Technology Commercial Scale Pilot-Geotechnical Deposit Performance. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 7–10 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, I.; Schimpke, K.; Ver Strate, R. Strength Fain of Fine Tailings/Slimes Resulting from Secondary Compression. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Tailings and Mine Waste, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, M.A. Effects of Polymers on Short-and Long-Term Dewatering of Oil Sands Tailings. Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suthaker, N.N. Geotechnics of Oil Sand Fine Tailings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- MatWeb. Imerys EPK Kaolin. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/DataSheet.aspx?MatGUID=ffb851eaeaad4a7dbba94037a46f4ecd (accessed on 25 June 2024).

| Measurement | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| wL | Casagrande cup | wL is the water content at which 25 drops of the Casagrande cup are needed to close a gap in the soil created by a standard grooving tool. |

| wL | Fall cone | wL is the water content at which a 30°cone (80 g) penetrates 20 mm into the soil. |

| wP | Thread rolling | wP is the water content at which a thread of soil crumbles at a diameter of 3.2 mm. |

| Material | Description |

|---|---|

| Centrifuge cake (CC) | Tailings that have been densified by spinning in a high-speed centrifuge [1]. |

| Fluid tailings (FT) | Tailings that have undergone no additional treatment or modification prior to deposition [1]. |

| Thickened tailings (TT) | Tailings that have been treated by the addition of flocculant and subsequent settling of fine particles in a thickener [1]. |

| EPK Kaolin | A commercially available natural clay used in applications such as ceramics, agriculture, and manufacturing [49]. |

| Dean Stark (DS) [50] | Cold Extraction (CE) [50] | |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent | Toluene | Toluene (74%) Isopropyl alcohol (26%) |

| Method of bitumen removal | Extracted from solids by vapourized toluene | Mixed with solvent and centrifuged to separate from solids |

| Solids treatment after testing | Oven-drying at 105 °C | Air-drying at room temperature |

| Sample | CC | TT | FT | EPK Kaolin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR * | DS | CE | AR | DS | CE | AR | DS | CE | |||

| Dried | wL-FC † | 62.0 | 42.7 | 56.6 | |||||||

| wL-C ‡ | 67.2 | 44.2 | 60.5 | ||||||||

| wP | 19.4 | 14.9 | 16.9 | ||||||||

| Rewetted | wL-FC † | 67.6 | 47.9 | 59.1 | |||||||

| wP | 17.1 | 11.9 | 15.7 | ||||||||

| Rehydrated | wL-FC † | 64.7 | 62.9 | 64.0 | 57.4 | 62.2 | |||||

| wL-C ‡ | 59.8 | ||||||||||

| wP | 20.7 | 19.2 | 22.4 | 16.6 | 27.7 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paul, A.L.; Beier, N.A. Atterberg Limits and Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings. Mining 2025, 5, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040086

Paul AL, Beier NA. Atterberg Limits and Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings. Mining. 2025; 5(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040086

Chicago/Turabian StylePaul, Abigail L., and Nicholas A. Beier. 2025. "Atterberg Limits and Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings" Mining 5, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040086

APA StylePaul, A. L., & Beier, N. A. (2025). Atterberg Limits and Strength Relationships of Oil Sands Tailings. Mining, 5(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040086