Abstract

Mine closure is a growing concern in mining countries around the world due to the associated environmental and social impacts. This is particularly true in developing countries like South Africa where poverty, social deprivation and unemployment are widespread and environmental governance is not strong. South Africa has 230 operating mines located in diverse natural and social settings. Over 6 million people live in urban and rural mining host communities who will be significantly affected by mine closure. The national, provincial and local governments need guidance in identifying high-risk areas and relevant policy and programmatic interventions. This paper describes the development of a quantitative mine closure risk rating system that assesses the likelihood of mine closure, the risk of social impact and the risk of environmental impact of mine closure for every operating mine in the country. The paper visualises the high likelihood of closure and environmental impacts for numerous coal and gold mines, and the significant social risks in the deprived rural platinum and chrome mining areas. The rating system was tested with 10 mines and 19 experts, and the resulting maps are communicated in an online South African Mine Closure Risk and Opportunity Atlas. The risk ratings could be used in mine closure planning and management by mining companies, consultancies, governments and affected communities. While this risk rating system has been designed for South Africa, the methodology and framework could be applied to any mining country in the world.

1. Introduction

1.1. Mining in South Africa

South Africa has a long history of mining which has played a significant role in the location and development of settlements, infrastructure and the economy [1]. The mining sector contributes 7.53% of GDP, employs 475,561 people (4.8% of formal sector) and paid company tax of R73.6bn (USD4bn), royalties of R14.2bn (USD0.76bn) and employee earnings of R174.9bn (USD9.4bn) in 2022 [2]. South Africa is a globally leading producer of platinum and palladium (74% of 38% of global production respectively) [3], chromium (36%), manganese (36%) [4], zirconium (23%) [5], vanadium (9%) [6], diamonds (8%) [7], fluorspar (5%) [8], gold (3.5%) [9] and coal (3.2%) [10] and also produces iron ore, nickel, copper, lead, zinc and phosphate rock [11,12]. These commodities are mined at 230 underground and open pit mines operated by 104 private mining companies, nearly a third of which are coal mines while a quarter are platinum or chrome mines. These mines are supported or hosted by over 360 diverse urban and rural communities, across South Africa, which are home to over 6 million people. These communities are situated in three metropolitan municipalities and 635 local municipalities that have a total population of 27.1 million [13].

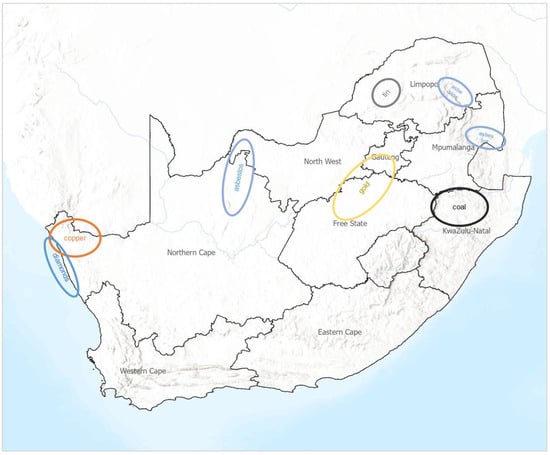

Since large-scale commercial mining began in South Africa in 1852, mine closure has occurred on a regional scale in the Okiep copperbelt (1852–1970s) and West Coast diamonds (1926–2010) in the western Northern Cape province; three asbestos fields in Mpumalanga, Limpopo and Northern Cape (1930–1980s); the Natal coalfields (1880–1980s); the Wits goldfields (1886–1990s) in Gauteng, North West and Free State provinces; and Rooiberg tin (1907–1994) in Limpopo province (see Figure 1) [1]. The country’s mineral wealth has not benefited communities equally and has had negative public health, safety and environmental impacts [14,15,16]. The derelict and ownerless asbestos and gold mines have been the focus of government rehabilitation efforts, but more needs to be done and the widely held view is that industry and government are not effectively managing mine closure [17,18,19] or providing sufficient socio-economic benefits to mining regions [20,21,22].

Figure 1.

Map of South Africa’s provinces and areas of historical mine closure.

Numerous coal mines are expected to close in the near future as the coal fields in Mpumalanga province are depleted and climate change limits coal investment; there is significant domestic and international pressure for a ‘just transition’ to clean energy that ensures that the mine workers and host communities are not left behind [23]. Similarly, the shift to electric vehicles may see a decline in platinum demand and result in mine closures in the high-cost underground mines in North West and Limpopo provinces. In other regions within South Africa, the increased global demand for so called ‘energy transition minerals’ is seeing increased exploration and development of manganese, copper, iron ore, base metals, vanadium and rare earth minerals, which are necessary for green energy and e-mobility technologies [24].

1.2. Mine Closure

Traditionally, mine closure has been seen as the end of a process—the final stage in the mining life cycle. There is a shift underway to seeing mine closure as a transition that acknowledges the multi-faceted role that mines play in local and regional economies, as well as the complex impacts, contributions and interrelationships that occur with society and governments [25]. The importance of mining companies building and sustaining relationships with local government and communities affected by mine closures is growing [26], and early stakeholder participation and continuous mine closure planning increases the success of social investment programmes [27].

Mining operations are affected by numerous environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks at multiple levels [28], and there are several factors that can influence when a mine closes. The major causes of mine closure are financial and economic, namely, price drops, high costs, resource exhaustion or depletion, declining grades and loss of markets; while other causes are adverse geological and/or geotechnical factors, voluntary administration, flooding, political decisions, and health and safety concerns [29]. In South Africa, gold and platinum mines have been negatively affected by price drops and escalating costs of deep underground mines, while gold, copper and coal mines have closed due to resource exhaustion [30,31], tin mines closed when the price collapsed [32,33] and asbestos mines were closed when the serious health implications were understood [34].

Globally, there are major concerns around potential impacts of future mine closures [35], and current best practice is that mine closure planning starts at the onset of mining activity and continues throughout mining operations [36]. Closure planning must consider environmental and socio-economic impacts and include economic diversification and succession planning, which have historically received little attention [15].

1.3. Mine Closure Risk

Managing risk is central to enabling a transitions-based approach to mine closure [25]. A key goal of mine closure for regulatory authorities and industry is the removing or reducing liability for residual risks and generating confidence for future environmental, social and economic management (ibid). Risk assessment and its application to mine closure have therefore increasingly become more important in mine planning [36,37]. Mine closure guidelines generally agree that effective data collection ensures that risks are managed and monitored [38,39,40], although the emphasis continues to be on environmental risk performance indicators, with socio-economic risks often understated [40,41,42].

The environmental and socio-economic risks associated with mine closure are significant and are affected by several inter-related factors. Mine closure can have significant environmental impacts on biodiversity, land and water resources involving water pollution, air pollution and land degradation. The most well-known risks in South Africa are acid mine drainage from gold and coal mines and tailings dam failures (most recently, Jagersfontein diamond tailings dam). Global assessments show that mining often operates near biodiversity-protected areas [43], water bodies [44,45] and sensitive land [46]. Mine closure can have significant social and economic impacts, including direct and indirect job losses; economic downturn in the communities and even the wider region; basic services disruption if the mining company was supporting or supplying services; and illegal mining which creates an unsafe environment for local residents [36,47,48]. Illegal mining in South Africa is focused on closed gold and diamond mines near populated areas.

The exposure to these hazards depends on how many people are affected, i.e., the population of mining host communities, and it is therefore very important how they are defined. The vulnerability or resilience of a community affects how well it can cope with the economic shock of mine closure, and local infrastructure and business activity determine post-closure economic prospects. Analysis of job prospects for coal mine workers in South Africa leaving mining show the majority are not employable or have low employability prospects [49]. Similarly, the financial and human resource capacity of local government authority affects its ability to cope with mine closure, and the resulting loss of revenue and analysis of audit reports in South Africa show most municipalities will struggle to cope [23]. Given these complexities, guidance is needed for national, provincial and local governments in identifying high-risk areas to mitigate these risks on a case-by-case basis.

This paper describes the development and proposition of a new Mine Closure Risk Rating System for South Africa, which has three components—likelihood of mine closure, social risk and environmental risk of closure. Section 2 provides the methodology for the development of the rating system which includes diverse influencing factors and their measurable indicators, weightings and categorisation, case studies and expert input. Section 3 provides the quantified results for each risk rating for all operating mines in the country, which are mapped in ArcGIS Pro. Section 4 discusses the measurement of mine closure risk, data gaps and future research, communication, stakeholder engagement and evidence-based decision-making, while Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

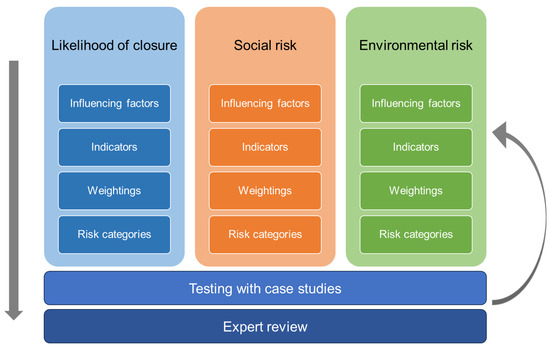

The methodology used to calculate mine closure risk ratings for all operating mines in South Africa is captured in Figure 2, which gives an overview of the risk rating system developed in this study. Each element is described below.

Figure 2.

Mine closure risk rating framework.

2.1. Influencing Factors, Indicator Selection and Data Collection

Risk is the possibility or likelihood of loss or harm and incorporates exposure to a hazard. In this study three components of risk are assessed for all operating mines in South Africa: the likelihood of mine closure, the likelihood and impact of social loss/harm from mine closure to mining host communities, and the likelihood and impact of environmental loss/harm from mine closure. Each component has a set of influencing factors which determine overall risk and were identified through literature review, case studies, a stakeholder workshop and expert interviews. Each influencing factor was measured using one or two indicators, where the criteria for indicator selection were: ‘Is the indicator the best available direct measure of the influencing factor?’ and ‘Are there sufficient reliable data that are measured for the whole country?’

The primary datasets for the rating systems are the 221 operating mines, the 360 mining communities, and 61 municipalities which have been built up over the past five years by the author [23,28,50,51] and expanded based on more recent mining company reports and community profiles in the 2011 Census. Secondary data were collected from numerous open-source national datasets identified below.

2.1.1. Likelihood of Closure

Seven factors influencing the likelihood of mine closure in South Africa were identified and are described below. Two factors, ‘social licence to operate’ and ‘political dynamics’, could not be quantified. Data were collected largely from company websites, company Social and Labour Plans, SLPs, (a South African regulatory requirement), and company annual reports on mineral resources and reserves (MRR).

Life of Mine: Each mine has a stated design life, the Life of Mine (LOM), which is the expected years of mine production based on the latest assessment of a mine’s mineral reserves. It is essential information for mine planning and investor reporting and should be shared with mining host communities. It includes a detailed assessment of economic, financial, technical and environmental factors and is normally reviewed annually, so is subject to change during the design life of the mine. Mine extensions (often from open pit to underground) can increase the life of mine considerably. It is the most important factor in determining likelihood of closure. Not all mines publish their life of mine figures, and where there were gaps, the highest risk rating was given, assuming the mine is operated by a junior miner on a small scale with a short life of mine.

Mineral Resources and Reserves: South Africa’s SAMREC Code provides minimum standards, guidelines and recommendations for the public reporting of exploration results, mineral resources and reserves [52]. The framework differentiates between an ‘exploration result’ with little information and low confidence in the basic geology; a ‘Mineral Resource’ estimate where a geological model is developed, with reasonable prospects for economic extraction; and a ‘Mineral Reserve’, which is an economically feasible project based on technical, economic, marketing, legal, environmental, social and governmental factors (Modifying Factors). Different commodities use different units in their MRR reporting due to the nature of the orebodies (e.g., million tonnes for coal but ounces for gold); therefore, five categories ranging from ‘very large’ to ‘very limited’ were developed in order to compare and rate the mines. Where no MRR was reported, the highest risk rating was given as it is likely that it is a smaller mine with limited reserves.

Commodity markets: Each commodity has different domestic and international markets that influence the commodity price and future demand, and thus the economic value of each mine’s MRR. Changes in the commodity markets have a significant impact on when a mine closes, and whether that is permanent or temporary closure. For example, when the tin price crashed in the 1970s, tin mines closed down rapidly across the world [32], and the huge variations in the gold price have seen mines close and reopen as viability changes [47]. With the threat of climate change and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, coal mines are likely to close sooner than expected, whereas copper mines are reopening as demand for energy transition metals rapidly increases [53], and new manganese mines have opened up rapidly in South Africa [54]. As there is so much uncertainty in the future commodity markets, each commodity was given a category: ‘high growth’, ‘growth’, ‘stable’, ‘decline’ or ‘rapid decline’, based on reliable market forecasts [55,56,57].

Operating costs and mining methods: The operating costs of mining operations vary significantly due to grade, mining method, depth of operation, recovery, labour efficiency, the use of subcontractors and input prices [58]. Conventional deep underground operations (like South African gold and platinum mines) are high-cost operations as they require refrigeration for ventilation and rock support, while mechanised operations are lower cost operations due to economies of scale. Mineral processing or treatment costs vary depending on the type of ore and the complexity of the process [59]. Industry cost curves can be plotted at a company or site level to facilitate cost comparisons [60]. Due to insufficient cost curves to generate a rating, mining method was used as a proxy for operating cost. The five main kinds of mining methods used in South Africa were rated, namely, open pit mining (usually low cost, low grade deposits), also called open cast mining; strip mining (most common method in coal mining); dredging (aquatic environments like ocean or river floors, often used for diamonds and heavy mineral sands); conventional underground mining used for deeper deposits (usually higher grade, higher cost deposits for coal, gold and platinum); and large-scale mechanised underground mining, which includes long-wall mining, sub-level caving and block caving (used for coal, diamonds and copper).

Company type: The type and size of a company partly determines its ability to accommodate changes in price, demand, operating costs and other factors that affect a mine’s financial viability. The larger companies are much more likely to weather a downturn than the smaller mining companies. Internationally, mining companies are categorised as majors, mid-tier producers and juniors, with majors usually have a market capitalisation of over USD 1 billion. The term “juniors” generally refers to exploration or prospecting companies only involved in the early stages of mining development, but in South Africa the term has a wider meaning and includes exploration companies and mid-tier producers. The term “emerging miners” is used in South Africa to refer to smaller companies involved in the early phases of mining exploration or in the early developmental stage i.e., smaller producing companies and contractors [61]. Three categories were used for the rating—majors, juniors and emerging miners—and are based on the Minerals Council South Africa report on juniors and emerging miners, which categorises all operating mines listed by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (ibid).

Social licence to operate: The relationship between the mining company and the local community can be a risk to mine operations. Protests about environmental pollution, damage, noise, jobs and local procurement are common in South Africa and are known to bring operations to a halt and result in significant loss of revenue, jeopardising the viability of the mine. Ideally the number and type of protests per mine would be measured across the country; however, these data are not currently available in a comprehensive form and could not be included.

Political dynamics: National and local politics can promote or hinder investment in mining operations, with corruption, political interference, political instability and regulatory uncertainty all deterring investment in mine expansions, thus leading to premature mine closure. The regulatory uncertainty and national politics apply equally to all mines in the country, so are not included as an indicator. It is difficult to measure political dynamics at the local level; thus, an indicator has not been included at this stage but should be investigated further.

2.1.2. Social Risk of Mine Closure

Mine closure can have significant social impacts on host communities and municipalities. The vulnerability or resilience of a community affects how well it can cope with the economic shock of mine closure—whether it is sudden or a long time in coming. Similarly, the capacity of the local government authority affects its ability to cope with mine closure and the resulting loss of revenue. Eight factors influencing the social risk of mine closure in South Africa were identified, and six were quantified with indicators. Data were collected from Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) household surveys, company websites and SLPs, local municipality publications and Auditor-General reports.

Mining host community population: The mining host community for each mine was identified based on its location and proximity to the mine, whether it is home to mine employees or is a beneficiary of the mine’s SLPs, and an assessment of the community and area in Google Earth. Setting a specific radius was not used as it can exclude communities that are close neighbours to other communities included in the definition. For data collection, ‘main places’ and ‘sub places’ defined by StatsSA for the 2011 census were used. Main places are small towns, townships, villages and suburbs in large towns and cities. They are subdivided into ‘sub places’, which can be specific areas like mines and compounds in urban and non-urban areas.

Social vulnerability: Fourteen indicators were used (see Table A1) to determine a score for social well-being in each mining host community, expanding on previous work by the author [50,51]. The indicator selection was based on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the South African Index of Multiple Deprivation (SAIMD) [62] and on data availability at the local level, i.e., in the national census. They cover income, household goods, health, education, gender equality, water access, sanitation, electricity access, clean cooking fuel, employment, housing, refuse removal and internet access. Census data at main place and sub place level in StatsSA’s SuperCross Census 2011 Community Profile Database were obtained from DataFirst, which provides access to household survey data in Africa (DataFirst, 2015). The individual values were equally weighted and combined into an overall well-being score for each community and assigned to each mine.

Direct mining jobs: The more mine workers there are in a community, the bigger the social impact will be when a mine closes. Although most of the major mining companies report the current number of employees in their annual reports and on their websites, the junior and emerging miners do not. Instead, the Census 2011 data on employment in mining and quarrying per main place were used. This is not ideal as it usually gives higher numbers than the individual mine accounts for, and thus it has been given a low weighting. This dataset should be updated with the Census 2022 community database. An alternative indicator is the percentage of jobs in mining and quarrying to reflect the varying impact on the area. Future research should seek to obtain job numbers for individual mines.

Indirect mining jobs: Operating mines form part of a much bigger value chain, relying on upstream and downstream industries. They have a multiplying effect on employment which can be estimate at the national and regional level. Data do not exist yet at the mine site level and therefore are not included in the rating.

Dependency ratio: The dependency ratio relates the number of children (aged 0–14) and the number of older persons (aged 65 and over) to the working age population (persons aged 15–64). The ratio highlights the potential dependency burden on workers—a high dependency ratio indicates that the economically active population and the overall economy face a greater burden to support and provide the social services needed by children and by older persons who are often economically dependent [63]. This ratio was calculated for each community using the Census 2011 dataset and should be updated with the 2022 census data at the main place level.

Skills and education levels: The skills and education levels of mine workers and community members will affect their ability to find employment or create a business after the mine has closed down. SLPs provide detailed information about skills levels of all mine employees; however, the majority of SLPs are not publicly available. There is no available national skills dataset that could be used for the mining communities; thus, research is needed before this can be include in the rating.

Local economy: Mines can have a significant impact on a local economy through supply chain procurement and mine employee expenditure. Gross Value Added (GVA) measures the contribution of a corporate subsidiary, company, or municipality to an economy, producer, sector, or region, and is often reported on an annual basis in local municipality Integrated Development Plans (IDPs). As not all IDPs report this figure, an alternative dataset was used. stepSA provides local economic data in a national spatial dataset using CSIR’s mesozones (a complete grid of 25,000 spatial units ~50 km2) and economic data by sector [64]. This gives an indicator of economic production per sector expressed in Rands per mesozone. The mine dataset was overlaid on the mesozones in ArcGIS Pro.

Local municipality audit findings: A local government’s ability to cope with mine closure and to mitigate the risks can be assessed through its current financial performance. Each year, the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) assesses the financial management and performance management of all the country’s municipalities and rates them according to set definitions [65]. These ratings were assigned to each mine based on the local municipality that they are located in.

Crime and Safety: Illegal mining and the associated crime can be a consequence of mine closure. Some commodities like diamonds and gold are more prone to illegal mining as the valuable minerals and metals are easy to extract. The approach taken by the national and local police force is critical in whether illegal mining takes place but is hard to measure. Illegal mining often opens up mine shafts and pits to the public, which poses a safety hazard. Similarly, poorly rehabilitated mines can also pose safety and health risk to mining communities, but this is hard to predict. There is no available national dataset, which is an area for future research.

2.1.3. Environmental Risk of Mine Closure

Mine closure can have significant environmental impacts on biodiversity, land and water resources involving water pollution, air pollution and land degradation. Determining a risk rating for each mine is complicated due to the mismatch of scales and the uncertainty over extent of impact. Nine influencing factors were identified, and seven measurable indicators were defined.

Duration of mining: The longer a mine has been operating, the greater the likelihood of environmental impact. The start date of each mine, and any periods of temporary closure, were determined from in-depth research into mines and host communities based on the author’s previous research [1,51] to calculate the total duration of mining for each mine in years.

Threat status of terrestrial ecosystems: The National Biodiversity Assessment of 2018 delineated areas of different ecosystem threat status across the country for terrestrial, aquatic and marine ecosystems [66]. The author’s mine location dataset was overlaid on the threat status for terrestrial ecosystems shapefile provided by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) BGIS portal in ArcGIS Pro (desktop GIS software developed by Esri) to provide a status for each mine.

Distance to protected areas: In South Africa, protected areas are defined and maintained by the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment (DFFE) and SANBI. The author’s mine location dataset was overlaid on the latest 2023 protected areas shapefiles [67], and the distance from each mine to the nearest protected area was measured in ArcGIS Pro.

Distance to Strategic Water Source Areas: Mining often negatively impacts on local and regional water resources. In South Africa, surface and groundwater Strategic Water Source Areas (SWSA) have been identified [68]. The authors’ mine location dataset was overlaid on the SWSA shapefiles provided by SANBI’s BGIS, and the distance from each mine to the nearest SWSA was measured in ArcGIS Pro.

Mine Water Threat: The South African Mine Water Atlas provides risk ratings for each quaternary river catchment that lies within the boundary of assessed mineral provinces [69]. It is presented as key thematic maps including “mineral risk” indicating the assessed risk of acid production and/or leaching of constituents, “groundwater vulnerability” and “surface water threat” reflecting the vulnerability of those water sources to the type of mining activities (depth of mining is considered to have major varying impacts on aquifer systems) and ”mine water threat” which combines all the factors into a risk rating [69]. These threats are rated from ‘low or insignificant’ to ‘moderate low’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘high’ and to ‘very high’ (ibid). The groundwater vulnerability ratings are separated into surface mining (<100 m below ground level) and underground mining (>100 m below ground level). The mine water threat risk ratings for groundwater (surface mining), groundwater (underground mining) and surface water were determined for each mine in ArcGIS Pro by overlaying the mines dataset on the relevant shapefiles and then combined to give a cumulative mine water threat rating.

Agricultural production and land capability: Agriculture can be significantly hindered by mining and mine closure through water and air pollution and land degradation. The current agricultural production gives an indication of the potential negative environmental impact of mine closure. Insufficient data could be sourced to measure agricultural production at the local level, so the national land capability classification was used instead. It uses soil, climate and terrain to differentiate between arable land suitable for cultivation (classes I, II and III), marginal land suitable for light cultivation (classes IV), grazing land (classes V, VI and VII) and wilderness (class VIII) [70]. Mine locations were overlaid on the national land capability map in ArcGIS Pro [71] to determine the land capability class for each mine.

Waste stability: Many large-scale mines produce significant amounts of waste rock and billions of tonnes of mine tailings (a slurry of rock, water and chemicals) stored in dams or tailings storage facilities (TSFs), which have the potential to fail if not designed or managed properly [72]. Factors affecting the stability of TSFs include exposure to earthquakes, tropical cyclones, high winds, heavy rainfall and steep terrain, and these five factors can be measured with global datasets and combined to form a TSF failure risk rating [73]. In addition, post-closure design life of the TSF, key design elements of the TSF such as spillways and management of the TSF are important factors to consider. A waste stability rating was not included in this version of the rating system due to an incomplete TSF and waste rock dump dataset, and this is an area of future research.

Waste volume: The total volume of rock waste dumps and TSFs at each mine affects the potential environmental impact in terms of water pollution, dust pollution and risk of failure [72]. This is a difficult parameter to measure although the Global Tailings Portal now provides information for the major mining companies [74]. Separate research projects are underway to develop this further for South Africa (e.g., [54]), and an indicator was not included in this rating.

Capacity and approach of mining company: The capacity and management approach of the mining company responsible for closure will determine the effectiveness of rehabilitation and water and waste management during the closure process. This is difficult to measure, and an indicator was not included at this stage but should be investigated. The presence of a risk assessment in the mine closure plan could be assessed. The financial provisions for each mine, a regulatory requirement in South Africa, should give an indication of the ability of the mine to undertake effective rehabilitation, but the data are hard to find and require further research. The capacity of government to monitor and enforce environmental regulations was not included as a factor as it is a national government function and therefore the same for all mines.

2.2. Calculations, Weightings and Visualisation

The risk rating for each component was calculated for all operating mines based on the indicators and data described in the previous section. A rating scale from 1 (very low risk) to 5 (very high risk) was developed by the author for each indicator, and a weighting was applied based on the literature, statistical analysis of all mines in Microsoft Excel, and expert input. The five rating categories were assigned based on analysis of all the mines and sub-division into five quintiles of roughly equal numbers. The weighted indicators for each risk rating were combined to create an overall score, shown in the equation below, which was categorised in the same way. The results were plotted on maps in ArcGIS Pro and colour-coded with warm to cool colours to enable communication and analysis.

where

- F is the influencing factor indicator;

- w is the weighting for the influencing factor indicator.

2.3. Case Studies

The risk ratings were tested against four case studies of post-closure land use that included 10 operating mines with very diverse geographical contexts, mining methods, life of mine, and commodities [75]. The Impact Catalyst in Limpopo province project explores integrated game farming, agriculture and agro-processing initiatives to align with the platinum mine rehabilitation plan. The Community of Practice project explored the use of industrial crops for gold mine rehabilitation and downstream industries using multi-products from fibre and phytoremediation. The regional Bokamoso Ba Rona project in the West Rand goldfield proposes a multi-stakeholder collaborative approach for post-closure land use to create large-scale regenerative agriculture projects. The Green Engine in the Witbank coalfield in Mpumalanga province integrates post-mining land use, wate management, agriculture water treatment and industrial development. This testing using case studies improved the rating systems and ensured that the results reflected reality.

2.4. Expert Review

A draft risk rating was presented to the research project reference group—comprising eight academic, government and industry experts with significant experience in the field of mine closure—for feedback. The risk rating system was revised based on their input and presented in an online stakeholder workshop in March 2023. Over 70 mine closure experts in the mining industry, consulting, academia, civil society, and government were invited, and 32 confirmed their attendance. Although only 15 people attended on the day, they represented a balanced spread across academia, consulting, civil society and the mining industry. Participants were asked to answer questions about each draft risk rating using Zoom’s Advanced Poll functionality. At the end of the workshop, the participants were asked whether they would be willing to participate in expert interviews and if they could suggest further resources that could contribute to the development of the risk rating system. All of the participants completed all of the polls, and many of them gave additional feedback at the end of the workshop. One major advantage of holding an online workshop was that it ensured that all stakeholders voices were heard. It also meant that the workshop was recorded, and all the input was received in a digital format that is easy to analyse. The results from the workshop were collated and analysed and used to improve the risk rating system. Follow-up semi-structured interviews were conducted with four experts in local government, multilateral agencies, and an industry association to further refine and improve the rating system. The expert feedback on influencing factors and indicators from all the engagements was used to revise and improve the risk rating system.

3. Results

3.1. Operating Mines and Mining Communities

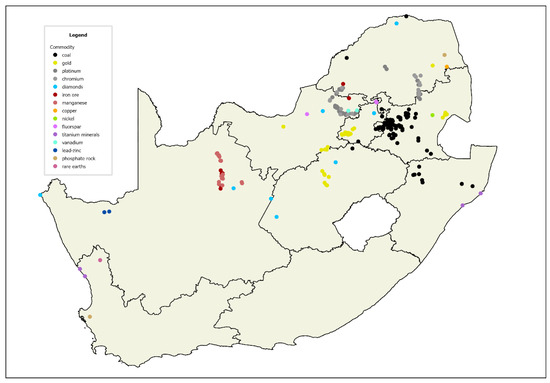

The risk ratings were based on an evolving database of operating mines (not quarries or alluvial diggings) and mining host communities in South Africa, developed over the past five years by the author [23,28,50,51]. The operating mines dataset includes mine name, province, local municipality, location, commodity, owner, mining duration, life of mine, host communities and population, well-being score, and information required to generate the risk ratings described in this paper. The list of operating mines, their data and the ratings generated in this study are given in Supplementary Material Table S1. The operating mines and host communities are summarised in Table 1 and Table 2 and mapped in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Summary of all operating mines and their host communities in South Africa.

Table 2.

Summary of all mining host local municipalities and metropolitan municipalities.

Figure 3.

All operating mines in South Africa.

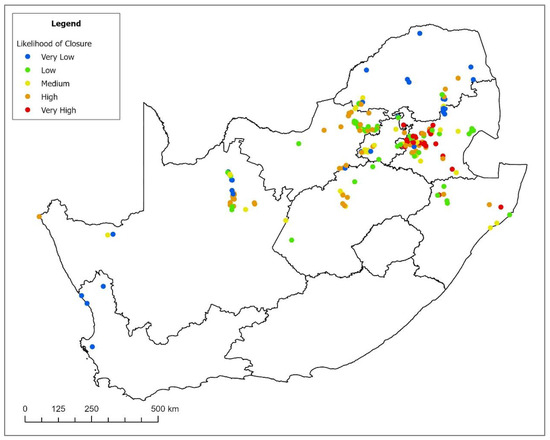

3.2. Likelihood of Closure

The likelihood of closure risk rating is shown in Table 3, and results for all operating mines are displayed on the map in Figure 4. The map shows clearly the high risk of closure in the Mpumalanga coal fields, the majority of gold mines and a few chrome mines on the Western Limb of the Bushveld Complex in North West province. The minimum rating was 1.2, the maximum rating was 4.8 and the average was 3.3. Of the 32 mines with a ‘very high’ rating, 29 are coal mines and three are gold mines. The mines with ‘high’ ratings are predominantly coal, gold and chromium mines, along with 10 relatively new manganese mines operated by emerging junior miners with limited published information, which may skew the results as the highest rating was assumed for data gaps.

Table 3.

Risk rating system for likelihood of mine closure.

Figure 4.

Likelihood of mine closure rating for all operating mines in South Africa.

3.3. Social Risk of Closure

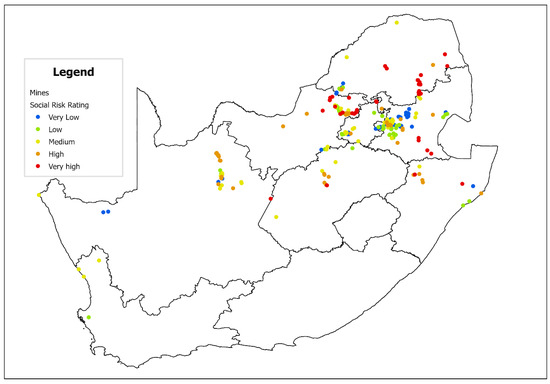

The socialrisk rating system is shown in Table 4 and the results calculated for all operating mines are displayed on the map in Figure 5. The map shows highest risk for mines surrounded by rural villages and lowest for mines near to cities. The mines with the ‘very high’ ratings are almost all platinum and chromium mines in North West and Limpopo provinces, as they are surrounded by deprived rural villages and have very large workforces. Notable exceptions are the copper and phosphate mines in Phalaborwa, which are two of the most remote mines, and two coal mines in eastern KwaZulu-Natal, which all have deprived rural communities. The manganese mines in Northern Cape have a ‘high rating’ due to their deprived rural communities and remote location. Although most gold mines have large workforces, their communities are better off with lower dependency ratios, and they are close to cities, so they have a ‘Medium’ rating. Similarly, the remaining coal mines are categorised as ‘Low’ or ‘Very low’ because they are hosted by small towns near cities, with higher levels of social wellbeing and lower dependency, and their workforce is relatively small compared to gold and platinum mines. These ratings are a first attempt at a national comparison of social risk and will require further testing and analysis in the future.

Table 4.

Risk ratings for socio-economic impacts of mine closure.

Figure 5.

Social risk of mine closure rating for all operating mines in South Africa.

3.4. Environmental Risks

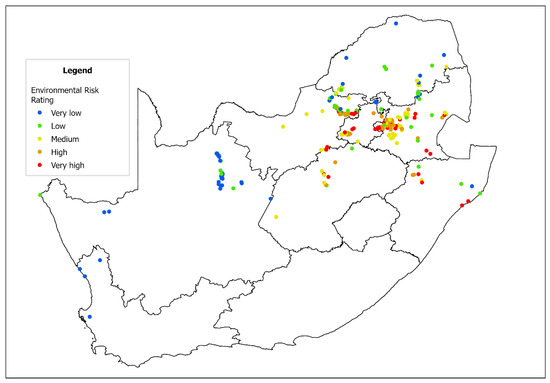

The environmental risk rating system is shown in Table 5 and the results calculated for all operating minesare displayed on the map in Figure 6. The map shows very high and high risk for gold and coal mines because of the risks of acid mine drainage to water resources and degradation of arable land. There are several platinum mines on the Western Limb in the North West province that also receive a high rating largely due to the threat to arable land, terrestrial ecosystems and protected areas. The lowest-risk areas are in the Northern Cape, where there is no arable land and the least threatened ecosystems, and Limpopo, where the mine water threat is low and there are no endangered ecosystems.

Table 5.

Risk ratings for environmental impacts of mine closure.

Figure 6.

Environmental Risk Rating Map for all operating mines in South Africa.

3.5. Case Studies

In order to test the draft risk rating system, the three ratings were calculated for all 10 mines in case studies. These mines have very diverse mine plans, social contexts and environmental settings, ensuring robust testing of the ranges and categories. The results given in Table 6 show ‘very high’ likelihood of closure for Khwezela coal mine and ‘high’ likelihood for Kusasalethu gold mine, which is due to close next year but has ore reserves that could extend the mine plan to 2037 if economic and political conditions improve. They show ‘medium’ likelihood for four other conventional underground gold mines, ‘low’ likelihood for the three new mines (two being highly mechanised gold mines that previously closed due to low gold prices and high operating costs), and ‘very low’ likelihood for Mogalakwena, which has a life of mine of over 70 years and low operating costs. The social impact risk ranges from low risk in some gold mines, with relatively better off communities located near the Gauteng metropolitan areas, to very high risk in Mogalakwena platinum mining areas in Limpopo, where the mines are surrounded by many very deprived communities with high dependency ratios. The environmental risk ratings range from very high for the gold mines located in Strategic Water Source Areas or areas with more threatened ecosystems or better arable land to low in the Mogalakwena platinum mining area, where there are low threats to water resources and ecosystems and the mines have been operating for a much shorter time.

Table 6.

Risk ratings for all mines in the case studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Measuring Risks Related to Mine Closure

This paper has described the development of a comprehensive mine closure risk rating system for South Africa and the quantification of three mine closure risk ratings for all operating mines in the country.

The likelihood of closure map identifies mines and areas where mine closure is highly likely and needs immediate attention. Out of the 221 operating mines that were rated, 48 are expected to close within 10 years, based on their current life of mine. This map is beneficial for government officials at local, provincial and national levels for policy, planning and budgeting, as well as for mining host communities that will be affected by closure. The map also shows that there are significant ranges in likelihood of closure within commodities and between commodities, and assumptions should not be made about imminent mine closure purely based on narratives around certain commodities. For example, gold mines that have been converted from conventional to mechanised mining now have long life of mines unlike their neighbouring conventional mines that are facing closure in the short term. This is important for the contested ‘just transition’ narrative in South Africa where it is assumed that coal mines will be forced to close, whereas it is much more likely that they will operate until the end of their current life of mine [23].

The social risk map reflects the potential negative impact that mine closure will have on neighbouring communities. There are at least 360 mining host communities in South Africa, but they have very diverse characteristics in terms of living standards and location. For example, those communities located in urban hubs with diverse economies will be less affected than the rural communities in remote areas. More importantly, historically disadvantaged communities (rural villages and townships) are still more deprived today and are much more vulnerable to mine closure and its resulting job losses and economic downturn. Given South Africa’s extreme inequalities, it is essential that, when site-specific studies are done on social risk of closure, the socio-economic baseline of each individual community is taken into account.

The environmental risk map reflects the potential negative impact that mine closure will have on the natural environment and enables the prioritisation of mitigation and intervention measures by mining companies and government. The focus of this risk rating system is to compare risks across all mine sites, and therefore it requires comprehensive, national standardised datasets. It does not account for localised environmental concerns although the general themes are captured in the risk rating. Ideally, once the high-risk mines are identified, detailed environmental assessments should be undertaken for each site. In South Africa, many of these reports commissioned by mining companies for mining licences are publicly available and can be used for further investigations.

4.2. Data Gaps and Future Research

It is important to note that this risk rating system is intended as a first version of a proposed risk framework for South Africa, and it is expected that it will be reviewed and improved over the years to come. While 17 indicators could be measured and quantified with existing or developed national datasets, there were gaps and opportunities for adding further aspects to the risk ratings. For likelihood of closure, ideally the operating cost of every mine should be captured instead of the mining method proxy used here, and more definition on mining companies would improve the accuracy of the company stability indicator. For social risk, the social data on communities came from the 2011 census, the only local-level national dataset. This should be updated when the 2022 census database is published. For environmental risk, threat to agricultural production, waste volumes and tailings dam failure risk all require comprehensive national datasets to be used in the rating system. Potentially a separate National Waste Atlas could be developed to focus on the risks and opportunities related to mine waste facilities [54]. Finally, given the huge impact of governance on mine closure outcomes, a governance risk component could be added to the risk rating system. This would look at corporate governance, local government capacity and provincial policy. If the rating systems were expanded to other countries, then national indicators would become important. Additional research could include correlation analysis between commodities, provinces and regions to better understand the risks and implications for different areas and sectors.

4.3. Communication, Stakeholder Engagement and Decision-Making

As social, environmental and governance aspects of mine closure are intertwined, the weightings need to be reviewed, and the local contexts must be considered. The weighting of factors may differ across local contexts, and therefore, critical engagement by mine closure stakeholders with the risk ratings is essential. Mine closure decision-making tools should be used in conjunction with efforts to build relations in or among communities potentially impacted by mine closure, and time should be given to the participatory process to ensure as wide an input as possible.

The risk rating maps described in this paper have been incorporated into an online Mine Closure Risk and Opportunity Atlas that can operate on a computer, tablet or smartphone to allow them to be communicated to a wide audience [76]. The Atlas has all the datasets used to calculate the risk ratings so that a user can interrogate the individual risk factors and make their own assessments to support mine closure planning and aid decision-making processes at all scales. Making information about mine closure risks and opportunities accessible to mining host communities, particularly through the Atlas being supported on smartphones, empowers them to engage in and influence decision-making processes. Showing the evidence for socio-economic deprivation in mining host communities to mining companies gives them the understanding and motivation to do more to support these communities when mine closure occurs.

There are numerous areas in the South African mining policy and planning arena where this risk rating system can be applied. It can be used in developing mine closure plans, undertaking environmental risk assessments and assessing financial provisions for rehabilitation of negative environmental impacts, all required by mining companies in South Africa under Regulation 11 (1) of Government Notice R1147. It can also be used by Future Forums designated in SLPs for engaging host communities in mine closure planning [77], in the development of Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) by local municipalities, and in regional spatial planning by district municipalities and provincial governments. Finally, it could play a supporting role in the implementation of the National Mine Closure Strategy by the national DMRE [78], which is being gazetted for another round of public participation in early 2024. There are several options for post-closure land use and economic diversification and job creation for different types of mines. These involve agriculture, forestry, tourism and recreation, conservation, energy supply, water storage, community and culture facilities, and research [79]. The risk ratings and their underlying datasets can contribute to the selection of viable opportunities as risk assessments are critical to mine closure planning [80].

5. Conclusions

This paper has described the development of a national mine closure risk rating system for South Africa to aid management and policy-making regarding mine closure in the country. The risk rating system identifies mines and regions where mine closure is highly likely and needs immediate attention, and provincial, district and local governments should take note of how this may affect their planning and budgeting in the short and medium term. Currently, 48 operating mines have a life of mine of 10 years or less, and the coal mines in Mpumalanga province and the gold mines in Gauteng stand out as areas requiring urgent attention. The rating system ranks mines by the risk of negative social and environmental impacts potentially resulting from closure, enabling the prioritisation of mitigation and intervention by mining companies and government. The social risks are highest in the most vulnerable communities, highlighting the need for a broad response by national and provincial governments that alleviate poverty and support economic growth. The environmental risks are highest for coal and gold mining regions, which are also where the best arable land is found, highlighting the importance of rehabilitation in the mine closure process to enable post-closure land use and economic diversification.

The risk ratings proposed here are a first attempt at a national comparison of likelihood of mine closure, social risk and environmental risk, and will require further testing and analysis in the future. Additional datasets will be required to fill gaps and ensure that the risk ratings capture all of the influencing factors. The results of the risk ratings could promote deeper discussions on mine closure management and planning among a diverse group of stakeholders and support evidence-based decision-making. Finally, while the risk rating system has been developed for South Africa, its concepts, design and insights could be applied to any mining country in the world.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/mining4010005/s1, Table S1: Data and risk ratings for all operating mines in South Africa.

Funding

This research was funded by the Water Research Commission, grant number C2021_2023-00475.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results will be made available in the online South African Mine Closure Risk and Opportunity Atlas, including links to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study.

Acknowledgments

The author would also like to thank all the experts and stakeholders who gave of their time and expertise, and the wider project team for their comments and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Indicators of social well-being for mining host communities [51].

Table A1.

Indicators of social well-being for mining host communities [51].

| Dimension and SDG Target | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Income (SDG 1.2) | % households with income more than R19,600/year (est. national poverty line) |

| Household goods | % households that own a refrigerator |

| Health | % population without a disability |

| Education (SDG 4.1) | % adults (≥20 years) with NQF4 qualification (Grade 12, NTC3) or better |

| Gender representation (SDG 5.5) | % of female councillors in local government |

| Water access (SDG 6.1) | % population with piped water in their dwelling or yard |

| Sanitation (SDG 6.2) | % population with access to a flush toilet or chemical toilet |

| Electricity access (SDG 7.1) | % population with electricity as main source of lighting |

| Clean cooking fuel (SDG 7.1) | % population using clean cooking fuel |

| Employment (SDG 8.5) | % labour force (including discouraged jobseekers) employed |

| Housing (SDG 11.1) | % population in formal housing |

| Waste management (SDG 11.6) | % population with refuse removal |

| Internet access (SDG 17.8) | % population with access to internet |

References

- Cole, M.J.; Broadhurst, J.L. Mapping and Classification of Mining Host Communities: A Case Study of South Africa. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerals Council South Africa. Facts & Figures Pocketbook 2022; Minerals Council South Africa: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Platinum-Group Metals Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Manganese; Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Zirconium and Hafnium; Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Vanadium; Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- SADPMR. Annual Report 2021/22; SADPMR: Kempton Park, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- USGS Fluorspar. Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USGS Gold. Mineral Commodity Summary; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- BP. Statistical Review of World Energy 2022, 71st ed.; BP: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yager, T.R. 2016 Minerals Yearbook the Mineral Industry of South Africa; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DMR. South African Mineral Industry 2016/2017 SAMI, 34th ed.; Department of Mineral Resources, Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018; ISBN 9780621450088. [Google Scholar]

- StatsSA. Census 2022: Provinces at a Glance; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023; ISBN 9780621413908. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, R.; Snyman, L. Rehabilitation and Mine Closure Liability: An Assessment of the Accountability of the System to Communities. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Mine Closure, Sandton, South Africa, 1–3 October 2014; Fourie, A., Tibbett, M., Weiersbye, I., Eds.; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, L.; Nel, E. The Dangers of Growing on Gold: Lessons for Mine Downscaling from the Free State Goldfields, South Africa. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, I.; Olalde, M. The State of Mine Closure in South Africa—What the Numbers Say. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2019, 119, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auditor-General South Africa. Report of the Auditor-General to Parliament on a Performance Audit of the Rehabiliation of Abandoned Mines at the Department of Minerals and Energy; Auditor-General South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- SAHRC. SAHRC National Hearing on the Underlying Socio-Economic Challenges of Mining-Affected Communities in South Africa; South Africa Human Rights Commission: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016; ISBN 9780080453705. [Google Scholar]

- IHRC. The Cost of Gold: Environmental, Health and Human Rights Consequences of Gold Mining in South Africa’s West and Central Rand; IHRC: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, J.; Kemp, D.; Marais, L. The Cost of Mining Benefits: Localising the Resource Curse Hypothesis. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, M.; Spencer, R.; Knowles, S.; Paull, M. Mining Legacies––Broadening Understandings of Mining Impacts. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, L.; Nel, V.; Rani, K.; van Rooyen, D.; Sesele, K.; van der Watt, P.; du Plessis, L. Economic Transitions in South Africa’s Secondary Cities: Governing Mine Closures. Polit. Gov. 2021, 9, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.J.; Mthenjane, M.; Zyl, A.T. Van Assessing Coal Mine Closures and Mining Community Profiles for the ‘Just Transition’ in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2023, 123, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MISTRA. The Future of Mining in South Africa: Sunset or Sunrise? MISTRA: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boggs, G.; Measham, T.; D’Urso, J. What Are We Transitioning into? Re-Thinking the Model of Mine Closure. In Proceedings of the Mine Closure 2023, Reno, NV, USA, 2–5 October 2023; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dzakpata, I.; Qureshi, M.; Kizil, M.; Maybee, B. Exploring the Issues in Mine Closure Planning; CRCTiME: Perth, Australia, 2021; ISBN 978-1-922704-05-4. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham, J.; Svobodova, K.; Mackenzie, S.; Witt, K. Participatory Processes for Mine Closure and Social Transitions; Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.J. ESG Risks to Global Platinum Supply: A Case Study of Mogalakwena Mine, South Africa. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, D. Optimisation of the Mine Closure Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, B. The Okiep Copper District Namaqualand, Northern Cape Province South Africa. Mineral. Rec. 2004, 35, 289–317. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. The Village in a Game Park: Local Response to the Demise of Coal Mining in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, L.M. Tin in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 1985, 85, 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Godsell, S. Rooiberg: The Little Town That Lived. S. Afr. Hist. J. 2011, 63, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abratt, R.P.; Vorobiof, D.A.; White, N. Asbestos and Mesothelioma in South Africa. Lung Cancer 2004, 45, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, D. ICMM Guidance and Resources for Integrating Closure into Business Decision Making Processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mine Closure 2021, Perth, Australia, 26–28 November 2021; Fourie, A., TIbbett, M., Sharkuu, A., Eds.; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ICMM. Integrated Mine Closure Good Practice Guide, 2nd ed.; International Council for Mining and Metals (ICMM): London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Western Australia. Statutory Guidelines for Mine Closure Plans; Government of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coppin, N. An Ecologist in Mining—A Retrospective of 40 Years in Mine Closure and Reclamation. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Seminar on Mine Closure, St. Austell, UK, 17–22 September 2013; Tibbett, M., Fourie, A., Digby, C., Eds.; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Cornwall, Australia, 2013; pp. 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, S.M.Z.; Rabbi, F.; Chowdhury, M.B. Mine Closure Planning and Practice in Canada and Australia: A Comparative Review. World Rev. Bus. Res. 2015, 5, 140–159. [Google Scholar]

- Manero, A.; Kragt, M.; Standish, R.; Miller, B.; Jasper, D.; Boggs, G.; Young, R. A Framework for Developing Completion Criteria for Mine Closure and Rehabilitation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 273, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bainton, N.; Holcombe, S. A Critical Review of the Social Aspects of Mine Closure. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, C.; Dowdell, E.; Monosky, M.; Keeling, A. Integrating Socio-Economic Objectives for Mine Closure and Remediation into Impact Assessment in Canada; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luckeneder, S.; Giljum, S.; Schaffartzik, A.; Maus, V.; Tost, M. Surge in Global Metal Mining Threatens Vulnerable Ecosystems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 69, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, M.G.; Thomas, C.J.; Mudbhatkal, A.; Brewer, P.A.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Lewin, J.; Scussolini, P.; Eilander, D.; Lechner, A.; Owen, J.; et al. Impacts of Metal Mining on River Systems: A Global Assessment. Science 2023, 381, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meißner, S. The Impact of Metal Mining on Global Water Stress and Impact Assessment. Resources 2021, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, E.; Harris, J.; Svobodova, K. A Global Vulnerability Analysis of Displacement Caused by Resource Development Projects. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, L. The Impact of Mine Downscaling on the Free State Goldfields. Urban Forum 2013, 24, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lèbre, É.; Owen, J.R.; Stringer, M.; Kemp, D.; Valenta, R.K. Global Scan of Disruptions to the Mine Life Cycle: Price, Ownership, and Local Impact. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4324–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schers, J.; Burton, J. Managing the Coal Transition for Workers in South Africa: A Scenario Analysis of Age Skills Profiles of the Coal Mining Workforce; International Association of Exhibitions and Events: Dallas, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.J.; Broadhurst, J.L. Sustainable Development in Mining Communities: The Case of South Africa’s West Wits Goldfield. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 895760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.J.; Broadhurst, J.L. Measuring the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Mining Host Communities: A South African Case Study. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAMREC. The South African Code for the Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves (THE SAMREC CODE); SAMCODE: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valenta, R.K.; Kemp, D.; Owen, J.R.; Corder, G.D. Re-Thinking Complex Orebodies: Consequences for the Future World Supply of Copper. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koovarjee, B.; Becker, M.; Von Holdt, J.R.; Petersen, J.; Cole, M. Developing a Mine Waste Atlas for the Northern Cape, South Africa. In Next Generation Tailings—Opportunity or Risk; SAIMM: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, K.; La Porta, D.; Fabregas, T.; Laing, T.; Drexhage, J. Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elshkaki, A.; Graedel, T.E.; Ciacci, L.; Reck, B.K. Resource Demand Scenarios for the Major Metals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2491–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune Business Insights Diamond Market Analysis and Regional Forecast 2023–2030; Fortune Business Insights: Maharashtra, India, 2023.

- Lonergan, W. The Valuation of Mineral Assets; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 2006; ISBN 9781920898267. [Google Scholar]

- Rudenno, V. The Mining Valuation Handbook; John Wiley and Sons Australia: Milton, Australia, 2012; ISBN 9780730377078. [Google Scholar]

- Tholana, T. Industry Cost Curves as a Tool to Analyse Cost Performance of South African Mining Operations: Gold, Platinum, Coal and Diamonds; University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kriel, H. The Extent, Nature and Economic Impact of the Junior and Emerging Mining Sector in South Africa; Minerals Council South Africa: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G.; Noble, M. The South African Index of Multiple Deprivation 2007 at Municipality Level; Department of Social Development, Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN ESA. Dependency Ratio. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/population/unpop.htm (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- STEPSA. CSIR SA CSIR MesoZone 2018v2; 2018. Available online: https://www.dpme.gov.za/keyfocusareas/gwmeSite/The%20PME%20Forum%202018/Annexure-Draft-NSDF-2018_September-2018-3.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Auditor-General South Africa. Consolidated General Report on Local Government Audit Outcomes MFMA 2020-21; Auditor-General South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Skowno, A.L.; Poole, C.J.; Raimondo, D.C.; Sink, K.J.; Van Deventer, H.; Van Niekerk, L.; Harris, L.R.; Smith-Adao, L.B.; Tolley, K.A.; Zengeya, T.A.; et al. National Biodiversity Assessment 2018: The Status of South Africa’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity—Synthesis Report; South African National Biodiversity: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019; ISBN 978-1-928224-34-1. [Google Scholar]

- DFFE Protected and Conservation Areas Database 2023; Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023.

- Le Maitre, D.; Seyler, H.; Holland, M.; Smith-Adao, L.; Maherry, A.; Nel, J.; Witthuser, K. Identification, Delineation and Importance of the Strategic Water Source Areas of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland for Surface Water and Groundwater; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018; ISBN 9780639200064. [Google Scholar]

- WRC. The South African Mine Water Atlas; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018; ISBN 9781431208067. [Google Scholar]

- Collett, A. The Impact of Effective (Geo-Spatial) Planning on the Agricultural Sector. In Proceedings of the South African Surveying and Geomatics Indaba, Kempton Park, South Africa, 22–24 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman, J.L.; van der Walt, M.; Monnik, K.A.; Thackrah, A.; Malherbe, J.; le Roux, R.E. Development and Application of a Land Capability Classification System for South Africa; Institute for Soil, Climate and Water: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, E.; Svobodova, K.; Pérez Murillo, G. Catastrophic Tailings Dam Failures and Disaster Risk Disclosure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 42, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lèbre, É.; Stringer, M.; Svobodova, K.; Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Côte, C.; Arratia-Solar, A.; Valenta, R.K. The Social and Environmental Complexities of Extracting Energy Transition Metals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GRID-Arendal Global Tailings Portal. Available online: https://tailing.grida.no/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Cole, M.; Chimbganda, T.; Esau, M.; Abrams, A.; Broadhurst, J. Developing National Mine Closure Risk and Opportunity Rating Systems for South Africa; Draft Final Report to the Water Research Commission; Water Research Commission: Cape Town, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Esau, M.; Cole, M.; Broadhurst, J.; Chimbganda, T.; Abrams, A. Developing a National Mine Closure Risk and Opportunity Atlas for South Africa. In Proceedings of the Mine Closure 2023, Reno, NV, USA, 2–5 October 2023; Abbasi, B., Parshley, J., Fourie, A., Tibbett, M., Eds.; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- CALS. Social and Labour Plan Mining Community Toolkit; Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS): Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DMRE. Publication of the Draft Mine Closure Strategy 2021 for Public Comments; Department of Mineral Resources and Energy: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, J.; Holcombe, S. Mining as a Temporary Land Use: A Global Stocktake of Post-Mining Transitions and Repurposing. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maybee, B.; Lilford, E.; Hitch, M. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Risk, Uncertainty, and the Mining Life Cycle. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 14, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).