Applications of Generative AI in Architectural Design Education: A Systematic Review and Future Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Keyword Search and Databases

2.2. Identification and Screening

- ADE#1: Records were filtered to include only English-language publications from the 2020–2025 timeframe, resulting in 302 documents.

- ADE#2: The results were further narrowed to peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers only, excluding conference papers, proceedings, and other non-article documents. This step reduced the dataset to 124 documents.

- Focus on AI or GenAI within architecture or architectural education.

- Relevant discussion of AI applications across the design stages: pre-design, conceptual design, design development, or production.

- Insights into pedagogical shifts, studio applications, or learning outcomes.

2.3. Eligibility and Final Inclusion

- The stages of the architectural design process.

- GenAI tools used and their educational applications.

- Gaps and opportunities for future research.

3. Findings

3.1. The Architectural Design Process

- -

- The pre-design analysis phase, which involves some tasks such as programming, design data collection and site analysis.

- -

- The conceptual design phase, which involves crafting and developing the initial conceptual model, including the design philosophy.

- -

- The design development phase, where the project’s characteristics, such as spatial organization and circulation, are clarified using two-dimensional (2D) drawings and three-dimensional (3D) massing models.

- -

- The design production phase, which includes refinement of the 2D drawings, 3D rendering of the project, and preparing presentation materials to effectively communicate the design.

- -

- -

- Interdisciplinary collaboration to offer multidisciplinary knowledge and foster teamwork skills [61].

- -

3.2. The Shift Towards Digitization in Architectural Design Education

3.3. The Use of GenAI in Architectural Design Education

3.3.1. Pre-Design Analysis

3.3.2. Conceptual Design

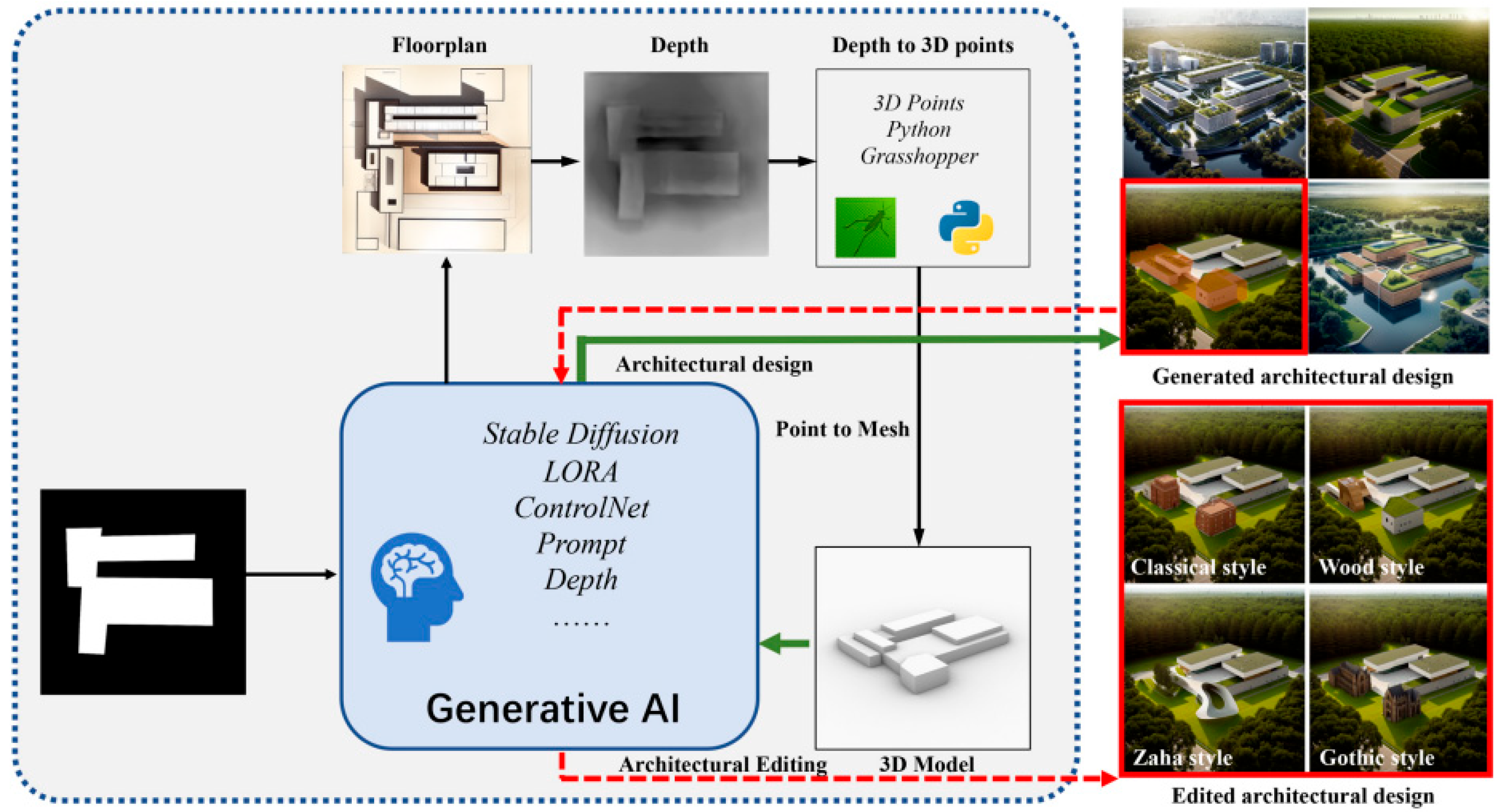

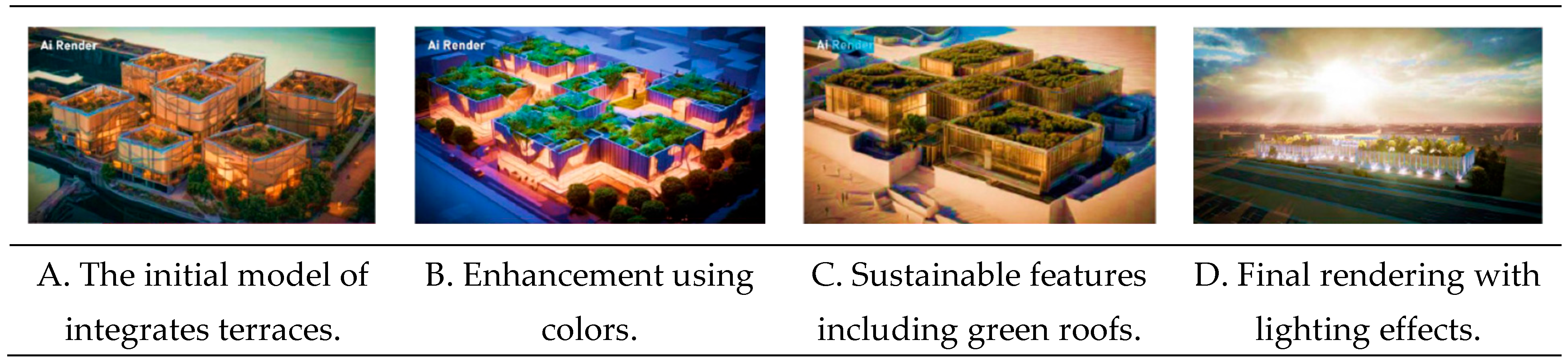

3.3.3. Design Development

3.3.4. Design Production

4. Discussion

- -

- Evaluating the long-term influence of GenAI on architectural education, including its effects on design thinking, creativity, and students’ engagement in the market.

- -

- Exploring the integration of GenAI across all stages of the architectural design process, particularly within the design development and refinement stages.

- -

- Examining best practices for pedagogy development that combine AI utilization with traditional design methods.

- -

- Developing ethical guidelines and educational frameworks that address the responsible use of AI-generated content.

- -

- Improve the readiness of academic institutions for AI utilization through professional development programs and policy support.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADE | Automatic Database Exclusion |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

References

- Chęć-Małyszek, A. Architecture as the art of creating human-friendly places, Lublin public space. Bud. I Archit. 2021, 20, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canestrino, G. Considerations on optimization as an architectural design tool. Nexus Netw. J. 2021, 23, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.L.N.; Utaberta, N. Learning in architecture design studio. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 60, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y. Research on the practice of the new education mode reform based on the teaching of architectural design course and the thinking of future architectural education. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouki, M.; Shiba, A.S.E.; Elboshy, B. An effective architectural criticism teaching framework link and enhance design skills. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2022, 54, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Soufi, N.; El Shafie, H. Assessment of the Current State of AI-Aided Design in Architecture Case Study: Design of a Residential Building in Riyadh City. J. Al-Azhar Univ. Eng. Sect. 2025, 20, 259–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaroussi, R.; Martín-Gutierrez, J. Architectural ambiance: ChatGPT versus human perception. Electronics 2025, 14, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braiden, H.; Chamberlain, B.; George, B.H.; Fernberg, P. AI in Practice: Professional Survey Findings from Landscape Architects in North America. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 2025, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.H.; Wang, L.; Lei, D. Conversational, agentic AI-enhanced architectural design process: Three approaches to multimodal AI-enhanced early-stage performative design exploration. Archit. Intell. 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deregibus, C. The Key Role of Keywords in Architectural Design: A Systemic Framework. Architecture 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moussaoui, M. Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence—An evolving practice. Open Eng. 2025, 15, 20240098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, D.; Ozar, B. A new frontier in design studio: AI and human collaboration in conceptual design. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 1536–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekesiz, G.; Müezzinoğlu, C. An approach to AI-supported learning in architectural education: Case of speculative space design. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2025, 22, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.K.C.; Yali, J.B.A.; Torres, V.S.M. Technology and Architecture: Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality on the Perception of Architectural Design. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 13, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, O.; Maier, A. Integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence into the Landscape Architecture Design Process. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 2025, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokry, R. Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Urban Design. JES J. Eng. Sci. 2025, 53, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, O.S. How artificial intelligence could affect the future of architectural design education. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Green Urbanism, Rome, Italy, 7–9 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassey, K.E.; Juliet, A.R.; Stephen, P.O. AI-Enhanced lifecycle assessment of renewable energy systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 2082–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Gao, X.; Yin, H.; Yu, K.; Zhou, D. Reimagining tradition: A comparative study of artificial intelligence and virtual reality in sustainable architecture education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar Kalenderoğlu, S.; Demiröz, M. Integrating Text-to-Image AI in Architectural Design Education: Analytical Perspectives from a Studio Experience. J. Des. Studio 2024, 6, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudzik, J.; Nyka, L. Artificial intelligence in architectural education—Green campus development research. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 26, 20–25. Available online: https://www.wiete.com.au/journals/GJEE/Publish/vol26no1/03-Cudzik-J.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Fareed, M.W.; Bou Nassif, A.; Nofal, E. Exploring the potentials of artificial intelligence image generators for educating the history of architecture. Heritage 2024, 7, 1727–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkarian, S. Enhancing architectural space through AI-driven ideation: A case study of future Iranian-traditional city. Rev. Amazon. Investig. 2024, 13, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, C.; Kasalı, A.; Doğan, F. Artificial Intelligence as a Pedagogical Tool for Architectural Design Education. J. Des. Studio 2024, 6, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Zairul, M.; Salih, S.A. Computational analysis of traditional architectural elements impact on AI-generated designs. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2024, 7, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Lee, J.-K.; Lee, Y.-C.; Choo, S. Generative artificial intelligence and building design: Early photorealistic render visualization of façades using local identity-trained models. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, I.; Yıldız, A. Artificial intelligence in architecture: Innovations, challenges, and ethical considerations. In Making Art with Generative AI Tools; Hai-Jew, S., Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Adibhesami, M.A.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Salehi, A.; Groppi, D.; Astiaso Garcia, D. Harnessing deep learning and reinforcement learning synergy as a form of strategic energy optimization in architectural design: A case study in Famagusta, North Cyprus. Buildings 2024, 14, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khogali, H.A. The effect of applying artificial intelligence in architecture college developing design process. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 17, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, B.; Li, Z. Sketch-to-architecture: Generative AI-aided architectural design. In Proceedings of the Pacific Graphics 2023, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 10–13 October 2023; The European Association for Computer Graphics: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maksoud, A.; Elshabshiri, A.; Saeed Hilal Humaid Alzaabi, A.; Hussien, A. Integrating an Image-Generative Tool on Creative Design Brainstorming Process of a Safavid Mosque Architecture Conceptual Form. Buildings 2024, 14, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, N. Integrative analysis of Text-to-Image AI systems in architectural design education: Pedagogical innovations and creative design implications. J. Archit. Urban. 2024, 48, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paananen, V.; Oppenlaender, J.; Visuri, A. Using text-to-image generation for architectural design ideation. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2024, 22, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płoszaj-Mazurek, M.; Ryńska, E. Artificial intelligence and digital tools for assisting low-carbon architectural design: Merging the use of Machine Learning, Large Language Models, and Building Information Modeling for Life Cycle Assessment tool development. Energies 2024, 17, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu Devi, A.; Maruthuperumal, S. Introduction to ChatGPT. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Omitaomu, F.; Sabri, S.; Zlatanova, S.; Li, X.; Song, Y. Leveraging generative AI for urban digital twins: A scoping review on the autonomous generation of urban data, scenarios, designs, and 3D city models for smart city advancement. Urban Inform. 2024, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwangsleitner, F.; Habjanič, G.; Knegendorf, A. AI as a Tool in the Landscape Architecture Design Process. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 2024, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölek, B.; Tutal, O.; Özbaşaran, H. A systematic review on artificial intelligence applications in architecture. J. Des. Resil. Archit. Plan. 2023, 4, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, E.B. Interview with Chat GPT to define architectural design studio work: Possibilities, conflicts and limits. J. Des. Studio 2023, 5, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derevyanko, N.; Zalevska, O. Comparative analysis of neural networks Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL-E and ways of their implementation in the educational process of students of design specialties. Sci. Bull. Mukachevo State Univ. Ser. Pedagog. Psychol. 2023, 9, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernberg, P.; George, B.H.; Chamberlain, B. Producing 2D Asset Libraries with AI-powered Image Generators. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 2023, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouki, M.; ElHaddad, T.A.; ElBoshey, B. Revolutionary artificial intelligence architectural design solutions; is it an opportunity or a threat? Mansoura Eng. J. 2023, 48, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meron, Y.; Tekmen Araci, Y. Artificial intelligence in design education: Evaluating ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for post-graduate course development. Des. Sci. 2023, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, J.; Đukanović, L.; Živković, M.; Žujović, M.; Gavrilović, M. Automated compositions: Artificial intelligence aided conceptual design explorations in architecture. In Proceedings of the 9th International Scientific Conference on Geometry and Graphics MONGEOMETRIJA 2023, Novi Sad, Serbia, 7–10 June 2023; Serbian Society for Geometry and Graphics SUGIG: Belgrade, Serbia, 2023; pp. 103–115. Available online: https://raf.arh.bg.ac.rs/bitstream/handle/123456789/1282/bitstream_4420.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Rane, N. Potential role and challenges of ChatGPT and similar generative artificial intelligence in architectural engineering. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. 2023, 4, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, T.B.; Gocer, O.; Sadrieh, A.; Globa, A. Leveraging AI to instruct architecture students on circular design techniques and life cycle assessment. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Higher Education Advances, Valencia, Spain, 19–22 June 2023; Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València: València, Spain, 2023; pp. 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhanta, W.C.; Hadinata, I.Y. Computational methods and artificial intelligence in the architectural pre-design process (case study: House design). J. Artif. Intell. Archit. 2023, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baduge, S.K.; Thilakarathna, S.; Perera, J.S.; Arashpour, M.; Sharafi, P.; Teodosio, B.; Shringi, A.; Mendis, P. Artificial intelligence and smart vision for building and construction 4.0: Machine and deep learning methods and applications. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploennigs, J.; Berger, M. AI art in architecture. AI Civ. Eng. 2022, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Pena, M.L.; Carballal, A.; Rodríguez-Fernández, N.; Santos, I.; Romero, J. Artificial intelligence applied to conceptual design. A review of its use in architecture. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, T.; Kuys, B.; King, R. Generative artificial intelligence to enhance architecture education to develop digital literacy and holistic competency. J. Artif. Intellegence Archit. 2024, 3, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman, A.; Mansour, Y.; Eldaly, H. Generative vs. non-generative AI: Analyzing the effects of AI on the architectural design process. Eng. Res. J. 2024, 53, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Greiff, S.; Teuber, Z.; Gašević, D. Promises and challenges of generative artificial intelligence for human learning. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, A.M. Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, H.M.N. From Beginning to End: The Design Process; College of Architecture and Planning, University of Dammam: Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, E. Integration of theory courses and design studio in architectural education using sustainable development. SHS Web Conf. 2016, 26, 01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AboWardah, E.S. Bridging the gap between research and schematic design phases in teaching architectural graduation projects. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. Appropriate teaching and learning strategies for the architectural design process in pedagogic design studios. Front. Archit. Res. 2017, 6, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masatlıoğlu, C.S.E.; Balaban, Ö.C. Reflective thinking and self-assessment: A model for the architectural design studio. J. Des. Resil. Archit. Plan. 2024, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, J. Implementing a blended design studio model in architectural engineering education. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 37, 1–13. Available online: https://raf.arh.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/2496 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Badawi, A.M.; Abdullah, M.R. Interdisciplinary design education: Development of an elective course in architecture and engineering departments. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2021, 68, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervisoglu, C.D.; Yılmaz, E. Examining the effect of learning environment on student behaviour through comparison of face-to-face and online design studio. MEGARON/Yıldız Tech. Univ. Fac. Archit. E-J. 2023, 18, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, R.; Wright, A. Shutting the studio: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on architectural education in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 1173–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgonul, Z.; Carrasco, O. The multidimensional exploration methodology for architectural design studio education: An innovative teaching methodology proposal. SPACE Int. J. Conf. Proc. 2022, 2, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Saleh, M.; Abdelkader, M.; Sadek Hosny, S. Architectural education challenges and opportunities in a post-pandemic digital age. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S. Artificial intelligence: A brief review. In Analyzing Future Applications of AI, Sensors, and Robotics in Society; Musiolik, T., Cheok, A., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M. Emerging role of artificial intelligence. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2022, 20, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2023, 32, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, T.; Ibisch, A.; Meiser, C.; Wilhelm, A.; Zimmer, R.; Berghoff, C.; Droste, C.; Karschau, J.; Laus, F.; Plaga, R.; et al. Generative AI Models: Opportunities and Risks for Industry and Authorities; Federal Office for Information Security: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalota, F. A Primer on generative artificial intelligence. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banh, L.; Strobel, G. Generative artificial intelligence. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, H.K.; Keçecioğlu, Ö.F. Generative artificial intelligence: A historical and future perspective. Acad. Platf. J. Eng. Smart Syst. 2024, 12, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E. A crisis in education: Navigating the technological abyss in architectural design studio. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Cankaya Scientific Studies Congress, Ankara, Türkiye, 28–29 September 2023; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375059300_A_Crisis_In_Education_Navigating_The_Technological_Abyss_In_Architectural_Design_Studio (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Ceylan, S. Artificial intelligence in architecture: An educational perspective. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, CSEDU, Virtual Event, 23–25 April 2021; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başarır, L. Modelling AI in architectural education. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2022, 35, 1260–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.T.; Kurtulus, S.; Karabay, E.; Özdemir, S. Integrating AI image generation to first year design studio: “invisible cities” reimagined with AI subtitle. In Proceedings of the ASCAAD 2023, Amman, Jordan, 7–9 November 2023; Available online: https://papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/ascaad2023_060.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Lukovich, T. Artificial intelligence and architecture towards a new paradigm. YBL J. Built Environ. 2023, 8, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkar, A.W.; Fareed, M.W.; Yahia, M.W.; Mushtaha, E.; de Giosa, S.L. Artificial intelligence Islamic architecture (AIIA): What is Islamic architecture in the age of artificial intelligence? Buildings 2024, 14, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.; Saleh, A. Evolution of AI role in architectural design: Between parametric exploration and machine hallucination. MSA Eng. J. 2023, 2, 262–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjani, H.; Nabizadeh, A.H. Towards human-centered artificial intelligence (AI) in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 11, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borglund, C. Artificial Intelligence in Architecture and Its Impact on Design Creativity: A Study on How Artificial Intelligence Affects Creativity in the Design Process; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Citation | Year | Country of Publication | Scope of the Study | Evidence Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al-Soufi & El Shafie [6] | 2025 | KSA | Examines the current implementation of AI-assisted design tools in architecture by analyzing their practical application through the design of a residential building in Riyadh. | Empirical |

| 2 | Belaroussi & Martín-Gutierrez [7] | 2025 | France/Spain | Investigates how ChatGPT’s interpretation of architectural ambiance compares to human perception, analyzing similarities, differences, and potential implications for AI-supported architectural design evaluations. | Empirical |

| 3 | Braiden et al. [8] | 2025 | Canada/USA | Presents findings from a professional survey of landscape architects in North America to examine current uses, perceptions, and future prospects of AI in landscape architecture practice. | Empirical |

| 4 | Cheung et al. [9] | 2025 | China | Explores three approaches for integrating conversational, agentic, and multimodal AI tools into early-stage performative architectural design processes. | Empirical |

| 5 | Deregibus [10] | 2025 | Italy | Develops a systemic framework that highlights the strategic use of keywords to organize, guide, and enhance decision-making within the architectural design process. | Conceptual |

| 6 | El Moussaoui [11] | 2025 | Italy | Examines how the integration of AI is transforming traditional architectural practice processes, focusing on the evolving relationship between designers and AI tools. | Conceptual |

| 7 | Karadağ & Ozar [12] | 2025 | Turky | Explores the collaborative potential between AI tools and human designers in the conceptual design phase within architectural design studios. | Empirical |

| 8 | Lekesiz & Müezzinoğlu [13] | 2025 | Turky | Presents an approach to integrating AI-supported learning in architectural education through a case study focusing on speculative space design. | Empirical |

| 9 | Rodriguez et al. [14] | 2025 | Peru | Examines how artificial intelligence and virtual reality technologies influence users’ perception and experience of architectural design. | Empirical |

| 10 | Schroth & Maier [15] | 2025 | Germany | Explores methods for integrating generative artificial intelligence into the landscape architecture design process to enhance creativity and efficiency. | Empirical |

| 11 | Shokry [16] | 2025 | Egypt | Investigates how AI influences urban design practices, with a focus on its potential to shape planning, analysis, and decision-making processes. | Conceptual |

| 12 | Asfour [17] | 2024 | KSA | Explores the potential impacts of AI on architectural design education, including design studio practice, student creativity, and the role of educators. | Conceptual |

| 13 | Bassey et al. [18] | 2024 | UK/USA | Examines how AI techniques improve the accuracy and efficiency of life cycle assessment (LCA) for renewable energy systems in the built environment. | Technical |

| 14 | Cao et al. [19] | 2024 | China | Compares the use of artificial intelligence and virtual reality in sustainable architecture education, focusing on how these technologies can reinterpret traditional design concepts and support learning. | Empirical |

| 15 | Çınar Kalenderoğlu & Demiröz [20] | 2024 | Turkey | Analyzes the integration of text-to-image AI tools in architectural design education through insights gained from a design studio experience. | Empirical |

| 16 | Cudzik & Nyka [21] | 2024 | Poland | Examines how AI tools support architectural education through a green campus development project, highlighting their role in conceptual design, sustainability analysis, and design production. | Empirical |

| 17 | Fareed et al. [22] | 2024 | UAE/Egypt | Investigate how AI image generators can be used as educational tools to support teaching architectural history by visualizing historical styles and concepts. | Empirical |

| 18 | Golkarian [23] | 2024 | Turkey | Explores how AI-driven generative ideation can support the development of architectural spaces inspired by Iranian traditional urban forms, using a case study to demonstrate concept generation and spatial design enhancement | Empirical |

| 19 | Günaydın et al. [24] | 2024 | Turkey | Examines the role of artificial intelligence as a pedagogical tool to enhance teaching and learning processes in architectural design education. | Conceptual |

| 20 | Jin et al. [25] | 2024 | Malaysia | Analyzes how traditional architectural elements influence the outcomes of AI-generated designs using computational methods. | Technical |

| 21 | Jo et al. [26] | 2024 | Korea/USA | Explores the use of GenAI models trained on local identity to produce early photorealistic renderings of building façades in the design process. | Technical |

| 22 | Karadag & Yıldız [27] | 2024 | Turkey | Provides an overview of recent AI innovations in architecture, discusses implementation challenges, and analyzes ethical implications. | Conceptual |

| 23 | Karimi et al. [28] | 2024 | Turkey/Iran/Italy/USA | Demonstrates the use of deep learning and reinforcement learning to optimize building energy performance during the architectural design process. | Technical |

| 24 | Khogali [29] | 2024 | KSA | Examine how integrating AI tools affects design development and learning outcomes in an architecture college setting, particularly in design studios. | Empirical |

| 25 | Li et al. [30] | 2024 | UK | Demonstrates how GenAI models can transform simple sketches into detailed architectural floor plans and 3D models, highlighting the workflow and potential of AI-assisted sketch-to-architecture processes. | Technical |

| 26 | Maksoud et al. [31] | 2024 | UAE | Examines the integration of an image-GenAI tool into the creative brainstorming process for developing a conceptual form of Safavid mosque architecture. | Empirical |

| 27 | Montenegro [32] | 2024 | Portugal | Provides an integrative analysis of text-to-image AI systems in architectural design education, focusing on their pedagogical innovations and impact on creative design processes. | Conceptual |

| 28 | Paananen et al. [33] | 2024 | Finland | Investigates the use of text-to-image generation tools to support ideation in architectural design processes. | Empirical |

| 29 | Płoszaj-Mazurek & Ryńska [34] | 2024 | Poland | Explores how AI combined with Building Information Modeling (BIM) can support low-carbon architectural design by improving life cycle assessment tools and processes. | Technical |

| 30 | Sindhu Devi & Maruthuperumal [35] | 2024 | India | Provides an overview of ChatGPT, its capabilities as a language model, and its potential uses and limitations across various fields. | Conceptual |

| 31 | Xu et al. [36] | 2024 | USA | Reviews how GenAI supports the autonomous creation of urban data, scenarios, designs, and 3D models to advance smart city development and urban design processes. | Conceptual |

| 32 | Zwangsleitner et al. [37] | 2024 | Germany | Examines the role of AI as a tool to support and enhance the landscape architecture design process. | Empirical |

| 33 | Bölek et al. [38] | 2023 | Turkey | Provides a comprehensive overview of how AI technologies are being applied across architectural design phases, with a focus on tools, methods, and potential benefits. | Conceptual |

| 34 | Caliskan [39] | 2023 | Turkey | Investigates the potential, challenges, and limitations of using ChatGPT as a knowledge source for shaping tasks in an architectural design studio. | Empirical |

| 35 | Derevyanko & Zalevska [40] | 2023 | Ukraine | Compares the features, capabilities, and educational applications of Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL-E for supporting design students’ creative work and visual outputs. | Conceptual |

| 36 | Fernberg et al. [41] | 2023 | /USA | Explores the use of AI-powered image generators for creating 2D asset libraries to support architectural and design workflows. | Technical |

| 37 | Desouki et al. [42] | 2023 | Egypt | Explores the dual role of revolutionary AI design solutions in architecture, analyzing whether they offer opportunities or pose risks to traditional design practice and creativity. | Conceptual |

| 38 | Meron & Tekmen Araci [43] | 2023 | Australia | Assesses the feasibility and effectiveness of using ChatGPT-4 as a collaborative virtual colleague to assist educators in developing postgraduate design studio courses. | Empirical |

| 39 | Milošević et al. [44] | 2023 | Serbia | Explores how AI tools automate and expand conceptual design explorations in architecture by generating diverse design compositions and solutions. | Technical |

| 40 | Rane [45] | 2023 | India | Examines how ChatGPT and comparable GenAI tools can be used in architectural engineering, highlighting their roles, benefits, and the challenges they pose for integration. | Conceptual |

| 41 | Tabrizi et al. [46] | 2023 | Australia | Examines how AI tools can support teaching architecture students about circular design principles and conducting life cycle assessments to promote sustainability. | Empirical |

| 42 | Yudhanta & Hadinata [47] | 2023 | Indonesia | Investigates how computational methods and AI tools support tasks in the architectural pre-design phase, demonstrated through a residential design case study. | Technical |

| 43 | Baduge et al. [48] | 2022 | Australia | Reviews the integration of AI, machine learning, and smart vision technologies to improve efficiency, safety, and sustainability in the building and construction sector under Industry 4.0 frameworks. | Conceptual |

| 44 | Ploennigs & Berger [49] | 2022 | Germany | Examines how text-to-image GenAI tools can be integrated into architectural design workflows to support concept generation, visualization, and creative exploration. | Technical |

| 45 | Castro Pena et al. [50] | 2021 | Spain | Provides a comprehensive review of how artificial intelligence is applied to support and enhance the conceptual design stage in architectural practice. | Conceptual |

| No. | Source | Architectural Design Process Stages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Design Analysis | Conceptual Design | Design Development | Design Production | ||

| 1 | Al-Soufi & El Shafie [6] | √ | |||

| 2 | Belaroussi & Martín-Gutierrez [7] | √ | |||

| 3 | Braiden et al. [8] | √ | |||

| 4 | Cheung et al. [9] | √ | √ | ||

| 5 | Deregibus [10] | √ | |||

| 6 | El Moussaoui [11] | √ | √ | ||

| 7 | Karadağ & Ozar [12] | √ | |||

| 8 | Lekesiz & Müezzinoğlu [13] | √ | |||

| 9 | Rodriguez et al. [14] | √ | |||

| 10 | Schroth & Maier [15] | √ | |||

| 11 | Shokry [16] | √ | |||

| 12 | Asfour [17] | √ | |||

| 13 | Bassey et al. [18] | √ | |||

| 14 | Cao et al. [19] | √ | |||

| 15 | Çınar Kalenderoğlu & Demiröz [20] | √ | √ | ||

| 16 | Cudzik & Nyka [21] | √ | √ | ||

| 17 | Fareed et al. [22] | √ | |||

| 18 | Golkarian [23] | √ | |||

| 19 | Günaydın et al. [24] | √ | |||

| 20 | Jin et al. [25] | √ | |||

| 21 | Jo et al. [26] | √ | |||

| 22 | Karadag & Yıldız [27] | √ | |||

| 23 | Karimi et al. [28] | √ | |||

| 24 | Khogali [29] | √ | √ | ||

| 25 | Li et al. [30] | √ | |||

| 26 | Maksoud et al. [31] | √ | |||

| 27 | Montenegro [32] | √ | |||

| 28 | Paananen et al. [33] | √ | |||

| 29 | Płoszaj-Mazurek & Ryńska [34] | √ | |||

| 30 | Sindhu Devi & Maruthuperumal [35] | √ | |||

| 31 | Xu et al. [36] | √ | |||

| 32 | Zwangsleitner et al. [37] | √ | |||

| 33 | Bölek et al. [38] | √ | |||

| 34 | Caliskan [39] | √ | |||

| 35 | Derevyanko & Zalevska [40] | √ | |||

| 36 | Fernberg et al. [41] | √ | |||

| 37 | Desouki et al. [42] | √ | |||

| 38 | Meron & Tekmen Araci [43] | √ | |||

| 39 | Milošević et al. [44] | √ | |||

| 40 | Rane [45] | √ | √ | ||

| 41 | Tabrizi et al. [46] | √ | |||

| 42 | Yudhanta & Hadinata [47] | √ | |||

| 43 | Baduge et al. [48] | √ | |||

| 44 | Ploennigs & Berger [49] | √ | |||

| 45 | Castro Pena et al. [50] | √ | |||

| Design Stage | Dominant Tools | Evidence Type | Reported Educational Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-design | LLM chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT and comparable tools), multimodal agents; AI + VR; layout generators | Mostly empirical (studio/workshops, surveys/interviews) | Faster info gathering; prompt literacy; early decision support; context-aware analysis |

| Conceptual | Text-to-image generators (Midjourney/SD/DALL-E); prompting; hybrid analog + AI; parametric exploration tools | Mixed, empirical + technical comparisons + conceptual critiques | Expanded ideation; rapid visualization; creative exploration; risk of pattern recycling |

| Development | Parametric/Computational workflows (Rhino–Grasshopper, Dynamo); sketch-to-architecture pipelines (e.g., Stable Diffusion + Rhino/Grasshopper); performance/sustainability optimization models | Mostly technical/professional | Workflow acceleration; performance/sustainability support (learning outcomes are less reported) |

| Production | AI rendering/visualization platforms (LookX.AI, PromeAI, etc.); façade generation; asset libraries; ML + BIM + LCA tools | Mixed (educational + technical + practice-oriented) | Faster high-quality outputs; improved communication; reduced repetitive tasks; LCA learning support (often practice-oriented; requires code compliance verification) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alamasi, R.; Asfour, O.S. Applications of Generative AI in Architectural Design Education: A Systematic Review and Future Insights. Digital 2026, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital6010006

Alamasi R, Asfour OS. Applications of Generative AI in Architectural Design Education: A Systematic Review and Future Insights. Digital. 2026; 6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital6010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlamasi, Rawan, and Omar S. Asfour. 2026. "Applications of Generative AI in Architectural Design Education: A Systematic Review and Future Insights" Digital 6, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital6010006

APA StyleAlamasi, R., & Asfour, O. S. (2026). Applications of Generative AI in Architectural Design Education: A Systematic Review and Future Insights. Digital, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital6010006