Abstract

Cultural organizations have traditionally been viewed as resistant to change, often bound by legacy structures, public dependency, and non-commercial missions. However, recent advances in digital technologies—ranging from AI and VR to IoT and big data—are reshaping the operational and strategic landscape of these institutions. Despite this shift, academic literature has yet to comprehensively map how technological innovation transforms cultural organizations into practice. This paper addresses this gap by introducing the concept of the Cultural Organizational System (COS)—a holistic framework that captures the multi-component structure of cultural entities, including space, tools, performance, management, and networks. Using a PRISMA-based scoping review methodology, we analyze over 90 sources to identify the types, functions, and strategic roles of technological innovations across COS components. The findings reveal a taxonomy of innovation use cases, a mapping to Oslo innovation categories, and a quadrant model of enablers and barriers unique to the cultural sector. By offering an integrated view of digital transformation in cultural settings, this study advances innovation theory and provides practical guidance for cultural leaders and policymakers seeking to balance mission-driven goals with sustainability and modernization imperatives.

1. Introduction

In the digital era, the cultural sector—long associated with tradition, continuity, and preservation—is experiencing a profound transformation driven by technological innovation [1,2]. Museums, cultural centers, art institutions, and creative enterprises are increasingly integrating technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), Internet of Things (IoT), and data analytics to reimagine their functions, engage broader audiences, and sustain their operations in an evolving socio-economic context [3,4]. This shift signifies a new phase in the evolution of cultural organizations, where digital capabilities are no longer peripheral but serve as core enablers of strategic renewal and long-term resilience. However, these dynamics remain underexplored in scientific literature, as cultural organizations possess distinct characteristics that differentiate them from other organizational types [5,6].

Although innovation has been widely studied in the domains of manufacturing, services, and public administration [7,8], its role within cultural organizations remains relatively under-explored [9]. There is limited empirical and conceptual clarity around how and where technological innovation manifests across the multifaceted landscape of cultural institutions. Existing scholarships often adopt narrow or fragmented definitions—focusing on museums, galleries, or creative industries in isolation—without accounting for the interconnected components and functions that shape the full architecture of contemporary cultural organizations [10,11]. This makes it difficult to analyze innovation patterns systematically or to develop applicable frameworks for strategic management in the cultural domain. To address this gap, this study introduces and applies the concept of the Cultural Organizational System (COS)—an integrative model that encompasses cultural centers, institutes, enterprises, and organizations as unified, yet complex systems composed of spaces, tools, management structures, networks, and artistic manifestations. This paper addresses this gap by introducing the concept of the Cultural Organizational System (COS), drawing on systems theory [12] and institutional logics [13]. Drawing on an extensive literature review and structured analysis, the COS model enables a more holistic understanding of how technological innovations influence cultural institutions not only at the product or service level but also across organizational processes, strategic functions, and societal roles.

The aim of this study is twofold. First, we seek to map the types and distribution of technological innovations (e.g., AI, 3D printing, chatbots, smart devices) across the main components of COS. Second, we aim to explore the strategic functions that these innovations serve—whether they enhance visitor engagement, optimize internal operations, generate revenue, or contribute to community development and cultural preservation. This research is timely for three reasons. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated digital adoption in the cultural sector, compelling organizations to explore new modes of delivery and interaction. Second, policymakers across Europe and beyond are increasingly promoting innovation-driven models for cultural sustainability as part of broader creative economic strategies [14]. Third, the growing interest in hybrid forms of cultural production and participation—blending physical and digital experiences—raises new challenges for managing innovation in settings that are often resource-constrained and mission-driven. In response to these developments, we ask the following research questions:

- RQ1: What are the dominant types of technological innovation adopted by cultural organizational systems?

- RQ2: How are these innovations distributed across the different structural components of COS?

- RQ3: What strategic roles do technological innovations play in the sustainability and evolution of COS?

- RQ4: What are the common enablers and barriers affecting the innovation process in COS?

To answer these questions, we conduct a structured scoping review of literature, following PRISMA-based methods, and synthesize the findings into a multidimensional analysis that contributes both conceptually and practically to the field. By doing so, the study offers a new lens for understanding technological innovation in a historically overlooked sector and proposes actionable insights for managers, policymakers, and researchers working at the intersection of culture and technology. This research contributes to the advancement of innovation theory by introducing the COS framework as a holistic unit of analysis and demonstrating how technological innovation enables the strategic, operational, and societal goals of cultural institutions.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Framing Innovation in Cultural Organizations

Innovation in cultural organizations is a growing yet underexplored area in both the innovation management and cultural policy literature. Cultural organizations are increasingly expected not only to preserve heritage and promote artistic expression but also to demonstrate adaptability, societal engagement, and financial sustainability. This dual role—between tradition and transformation—makes innovation a strategic imperative for their survival and relevance in contemporary society [15].

Historically, innovation in the cultural sector was seen through the lens of artistic creativity and programming changes. However, recent scholarship emphasizes that cultural organizations also engage in broader innovation practices, including organizational restructuring, new business models, digital transformation, and marketing innovations [16,17]. These forms of innovation are not merely technical upgrades; they involve strategic shifts in how cultural value is produced, mediated, and consumed. At the same time, cultural organizations are embedded in complex ecosystems shaped by public policies, funding structures, stakeholder expectations, and community needs [18]. These institutional and resource dependencies influence their capacity to innovate. As Pfeffer and Salancik [19] argue, organizations must acquire resources to achieve their goals, and innovation can be a key mechanism for doing so. Moreover, innovation adoption in cultural settings often faces unique constraints [20] resistance to change, resource scarcity, low digital maturity, and conflicting institutional logics between cultural missions and commercial viability [10,21]. Yet, innovation is increasingly recognized as a critical driver for addressing these tensions—whether through improving visitor experiences, building new audience relationships, or enabling financial resilience.

Despite this growing importance, literature on innovation in the cultural sector remains fragmented. Terms such as cultural institutions, cultural organizations, cultural centers, and cultural enterprises are used interchangeably, often without theoretical distinction or clarity. This inconsistency poses a challenge for researchers aiming to analyze innovative practices systematically across different types of cultural actors. To build a coherent framework for innovation analysis in this sector, this study first addresses this definitional ambiguity. In the following section, we analyze the terminology used across the literature and propose a unified conceptual model: the Cultural Organizational System (COS). COS serves as a foundational lens for understanding how cultural organizations innovate—technologically, organizationally, and socially—in the face of changing demands, limited resources, and evolving audience expectations.

2.2. Definitions and Critique of Cultural Organization Terminology

In the literature, cultural organizations are referred to using a variety of terms, including cultural institutions, cultural centers, cultural enterprises, and cultural organizations. Although these terms are often used interchangeably, they originate from different contexts and emphasize distinct organizational features—such as mission, ownership, legal status, or market orientation. This semantic variation introduces ambiguity, particularly when attempting to assess innovation practices across diverse organizational types in the cultural sector. To address this issue, this study conducted a targeted review of definitions from both academic sources and policy documents. Table 1 presents a synthesis of commonly used terms, each accompanied by its formal definition and citation. This summary shed light on the inconsistency in the literature about the different institutionalization of cultural organizations and the significance of the COS as a systematic approach into their research.

Table 1.

Definitions of Cultural Centers, Institutes, Organizations, and Enterprises.

These definitions highlight both the diversity and the limitations of existing terminology. While cultural centers emphasize community engagement and spatial context, cultural institutions are often linked to preservation and traditional missions. Cultural enterprises focus on commercial viability, whereas cultural organizations broadly encapsulate artistic and managerial dimensions. Despite overlaps, none of these terms comprehensively address the systemic and innovative-relevant aspects of how culture is produced, managed, and disseminated today. This fragmented nomenclature complicates the task of analyzing innovation practices across organizational types. It also obscures how various cultural actors respond to pressures for digitalization, audience engagement, financial autonomy, and strategic renewal. The field lacks a unifying conceptual construct that allows researchers to move beyond surface-level distinctions and instead focus on the structural, operational, and contextual elements relevant to innovation.

To fill this gap, we introduce the concept of the Cultural Organizational System (COS) in the next section. COS is designed as an integrative framework that captures the systemic complexity of cultural organizations while enabling a focused analysis of technological and managerial innovations. By shifting the unit of analysis from labels to systems, COS facilitates a more consistent and theory-grounded exploration of innovation dynamics in the cultural sector.

2.3. Introducing the Cultural Organizational System (COS): Concept and Justification

In response to the fragmented and inconsistent terminology surrounding cultural organizations, this study proposes a new integrative construction: the Cultural Organizational System (COS). The COS concept is designed to provide conceptual clarity and a systems-level perspective that supports a more comprehensive analysis of innovation processes within cultural organizations. Rather than treating cultural institutions, centers, enterprises, and organizations as separate entities with siloed definitions, COS frames them as variations within a broader system. This system comprises a set of interrelated and interdependent components that together define the organizational, cultural, and technological fabrics of such institutions. It allows researchers and practitioners to shift the focus from the labels that describe these entities to the functions, capabilities, and strategic configurations they enact in pursuit of their missions.

Theoretically, COS draws on systems theory [12], which views organizations as open systems that interact dynamically with their environments. Cultural organizations receive input (funding, ideas, people, technologies), engage in transformative processes (curation, programming, education, outreach), and generate outputs (cultural values, public engagement, economic activity). These components are not static; they co-evolve with institutional logic, community needs, technological changes, and policy pressures. In this sense, COS serves as both a conceptual framework and an operational lens for analyzing how cultural organizations adapt and innovate over time. From an institutional logics’ perspective [13], COS also captures the hybrid nature of cultural organizations. It accommodates the often-conflicting rationales they must reconcile—artistic autonomy, public service, market responsiveness, and social inclusion. By focusing on systems rather than individual features, COS enables a better understanding of how innovation unfolds in environments where normative, cognitive, and material pressures intersect. Based on a comprehensive synthesis of the literature, this study defines a Cultural Organizational System (COS) as:

“An organizational structure that comprises two or more of the following interrelated components: physical space, cultural tools or artifacts, artistic manifestations or performances, art management mechanisms, and social or professional networks—regardless of ownership structure (public, private, or hybrid).”

This systemic configuration positions COS as more than a venue or administrative unit; it is a platform for cultural production, innovation, and social transformation. The COS concept captures the hybrid and dynamic identity of cultural organizations as they evolve in response to digitalization, audience fragmentation, funding volatility, and the democratization of cultural participation.

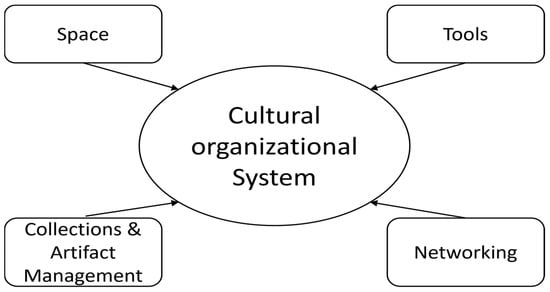

The introduction of COS is not only a terminological refinement—it enables a more rigorous and holistic innovation analysis. Most existing innovation models used in cultural contexts are borrowed from commercial or industrial settings and fail to account for the multidimensional nature of cultural production. COS overcomes this limitation by embedding innovation into a system of functions and relationships that are unique to the cultural domain. In subsequent sections, we operationalize the COS concept through a scoping review that maps how technological innovations are adopted and integrated into different COS components. This enables us to identify patterns, challenges, and opportunities that would otherwise be obscured by narrower or fragmented definitions. To visualize the multidimensional structure of cultural organizations as conceptualized by the COS framework, Figure 1 outlines the core components and their interrelations. The model integrates spatial, managerial, cultural, and social elements into a unified system that functions dynamically within broader environmental contexts. This systemic view enables a clearer understanding of how cultural organizations operate, evolve, and adopt innovation.

Figure 1.

Components of the Cultural Organizational System (COS).

As illustrated, the COS framework brings together key structural and functional elements necessary for innovation, readiness and sustainability in cultural organizations. In the following section, we expand this conceptual model into a systemic perspective, emphasizing the internal processes, external influences, and innovation flows that shape COS behavior over time. While Section 2.3 introduced the COS as a conceptual construct, Section 2.4 extends this view into a systemic model that emphasizes processes, inputs, outputs, and dynamic feedback loops.

2.4. The COS Model: A Systemic Perspective

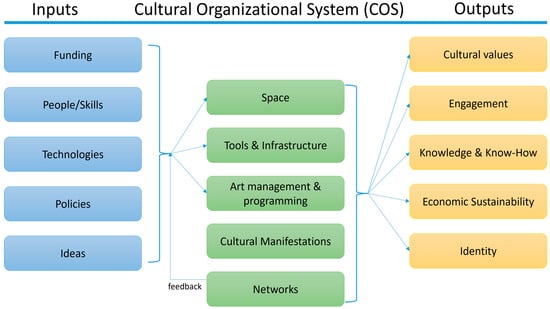

Building upon the COS definition and its core components presented in Figure 2, this section advances a systemic view of cultural organizations—one that situates them as dynamic, open systems embedded in complex socio-economic, technological, and institutional environments. Rather than treating innovation as an isolated event or a linear process, the COS model views it as a system-wide capability that emerges through interactions between internal elements and external influences. From a systems theory perspective [12], the COS operates through continuous input–throughput–output cycles. Inputs may include funding, policy mandates, digital infrastructure, partnerships, or emerging societal needs. These inputs are processed through a set of interrelated organizational components—spatial infrastructure, management practices, artistic production, cultural programming, and community engagement platforms. The outputs take the form of cultural value creation, knowledge dissemination, artistic expression, social inclusion, and, increasingly, economic sustainability.

Figure 2.

Methodological Flowchart: Identifying and Classifying Technological Innovations in COS.

Crucially, the COS is not static; it adapts through feedback loops triggered by shifts in audience behavior, technology availability, funding environments, and policy interventions. For example, the rising demand for hybrid and immersive cultural experiences has led many COS units to integrate technologies such as AR/VR, digital ticketing, AI-assisted curation, or data-driven audience analytics. These innovations are not adopted in isolation but require reconfiguration of internal processes, skills, and partnerships—highlighting the systemic nature of innovation in this domain. Moreover, the COS framework emphasizes the coexistence of multiple institutional logics [13]. On one hand, cultural organizations must uphold their civic mission, preserve heritage, and promote inclusivity. On the other, they face increasing pressure to act entrepreneurially, compete for attention in saturated media environments, and diversify revenue streams. Innovation, within the COS model, becomes the mechanism through which these logics are reconciled and rebalanced over time. This systemic lens also allows us to conceptualize innovation as occurring at multiple levels:

- Micro-level: innovations within specific units, teams, or service offerings (e.g., digitization of archives, social media marketing).

- Meso-level: organizational innovations such as new business models, participatory governance structures, or collaborative programming with schools and community groups.

- Macro-level: ecosystem-level changes involving partnerships with universities, local governments, or tech companies, as well as sector-wide digital infrastructure or policy reforms.

These three levels are interdependent. For instance, adopting an AI-powered audience segmentation tool (micro) may require new organizational roles and workflows (meso), which in turn may be supported or constrained by national digital culture strategies or EU funding schemes (macro). The COS model thus supports a multi-layered analysis of how innovations emerge, interact, and diffuse across the cultural sector.

By framing cultural organizations as systems with interlocking parts and adaptive feedback loops, the COS model provides a robust theoretical foundation for examining technological innovation in context. It enables the study of not just what innovations are introduced, but how, why, and under what constraints they are implemented. This is particularly important in a field where resource scarcity, mission heterogeneity, and stakeholder complexity often hinder linear innovation paths. In the following section, we apply this COS perspective to analyze technological innovation in cultural organizations based on a structured literature review. We explore how different types of technological innovation are being adopted, how they map onto the COS components, and what strategic purposes they serve across various cultural contexts.

Figure 3 illustrates the systemic functioning of the Cultural Organizational System (COS). The model conceptualizes cultural organizations as open systems, receiving inputs such as funding, people and skills, technologies, policies, and ideas. These inputs interact within the COS components—space, tools and infrastructure, art management and programming, cultural manifestations, and networks—where technological innovation is adopted and integrated. The processes generate outputs including cultural values, engagement, knowledge and know-how, economic sustainability, and identity. The arrows emphasize both directional flows and feedback loops, highlighting the dynamic and adaptive nature of COS in response to technological change and environmental pressures.

Figure 3.

Systemic view of the Cultural Organizational System (COS): inputs, processes, and outputs.

2.5. Technological Innovation in COS: Typologies and Trends

Technological innovation has emerged as a key enabler of change and resilience in the cultural sector, particularly within COS [2]. In a context marked by shifting audience expectations, funding instability, and the growing importance of digital engagement, COS increasingly turns to technology not only to enhance their offerings but also to secure their relevance and sustainability.

Traditional views of innovation in cultural organizations have primarily emphasized content-related improvements—such as new programming formats or curated experiences. However, technological innovation introduces a broader and more systemic transformation [33]. It encompasses the integration of digital tools, platforms, and infrastructures that reconfigure how culture is produced, distributed, experienced, and managed. Importantly, this goes beyond the mere digitization of archives or social media outreach; it includes intelligent systems for audience analytics, immersive technologies for engagement, and backend digital infrastructures that support agile governance and financial diversification. Building on the Oslo Manual [34], which outlines four major categories of innovation: process, organizational, and marketing, this study posits that technological innovation cuts across all these domains and deserves focused attention as a fifth, transversal category. It refers to the introduction or application of digital and scientific technologies that reshape the operations, services, or strategies of COS, often with limited R&D intensity but significant transformative potential. Technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data analytics, virtual and augmented reality, 3D printing, and blockchain are increasingly deployed in this space—not in isolation, but as catalysts for broader innovation pathways.

Technological innovation plays several critical roles within COS. It facilitates greater access and inclusion by expanding the reach of cultural content beyond physical boundaries. It enhances operational efficiency through digitalized workflows, customer relationship management tools, and cloud-based asset management. It enables more personalized and engaging experiences through AI-driven content curation, virtual exhibitions, or participatory online platforms. And importantly, it opens new revenue channels through digital memberships, hybrid events, crowdfunding, and online merchandising—helping COS navigate away from their traditional dependence on public subsidies. Despite these benefits, the adoption of technology in COS is not without significant challenges. Many organizations operate with constrained budgets and limit technical expertise. Staff may lack the digital literacy required to manage or maintain new systems, and institutional culture may resist changes that seem to threaten established artistic or curatorial practices. Moreover, the introduction of data-driven technologies often raises questions about the balance between mission and market, inclusivity and personalization, or authenticity and automation. These tensions highlight the complex environment in which technological innovation unfolds within cultural institutions.

The current body of research acknowledges the growing impact of technology in the cultural sector but remains fragmented. Studies often focus on emblematic institutions or on isolated use cases—such as the implementation of VR in museums or AI in audience targeting—without addressing how technological innovation integrates into the broader system of organizational components that define a COS. There is a clear need to explore how technology is adopted in a more systemic, interdependent way, not just outputs, but the very structure and strategy of cultural organizations. This study addresses that gap by adopting the COS framework as a lens through which to analyze the integration of technological innovations. By focusing on how these innovations interact with key elements such as space, tools, art management, and networks, the research aims to uncover patterns of transformation that may inform both academic understanding and managerial practice. In the next section, we outline the methodological approach taken to map and interpret this evolving landscape.

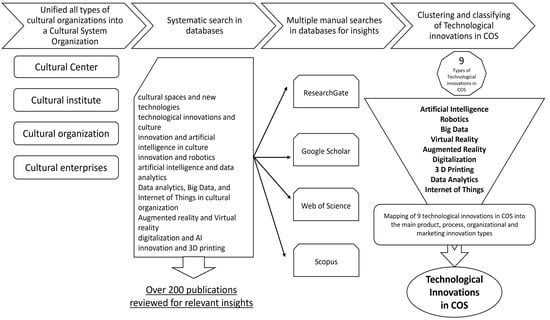

3. Research Design and Methodological Approach

To explore how technological innovations are adopted and integrated within Cultural Organizational Systems (COS), this study employs a structured qualitative research design grounded in a scoping review methodology. The aim is not only to map the breadth and nature of technological innovation practices in the cultural sector, but also to situate them within the systemic COS framework developed in the preceding sections. This approach allows us to identify emerging patterns, typologies, and tensions that characterize the digital transformation of cultural organizations, particularly as they navigate the dual imperatives of cultural mission and economic sustainability. Figure 2 presents a visual summary of the research process, from the conceptual integration of cultural organization types into the COS framework to the systematic identification and categorization of technological innovations.

Scoping reviews are especially appropriate for research areas that are complex, interdisciplinary, and under-theorized characteristics that apply to the intersection of culture, innovation, and technology. While the PRISMA-based scoping review offers a transparent and systematic process particularly suited to interdisciplinary topics [35], other methodological approaches are also well established in innovation management research. For instance, Taylor and Procter [36] outline a structured systematic review methodology commonly applied in social sciences, while bibliometric mapping methods such as the bibliometrix tool introduced by Aria and Cuccurullo [37] provide powerful techniques for analyzing publication networks and thematic clusters. These approaches could provide complementary perspectives, but they were not the focus of this study. Following the well-established framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley [38] and extended by Levac et al. [39,40], the research design follows a five-stage protocol: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies for inclusion, (4) charting the data, and (5) synthesizing and interpreting findings. The central research question guiding the review is:

How are technological innovations adopted across the different components of Cultural Organizational Systems, and what strategic purposes do they serve?

To address this question, we conducted a comprehensive literature search in academic databases including Scopus, Web of Science, JSTOR, and Google Scholar, focusing on peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and high-quality reports published between 2005 and 2024. The search terms included combinations of keywords such as technological innovation, cultural organizations, digital transformation, museums, creative industries, arts management, digital culture, virtual reality, AI in culture, and cultural sustainability. The search was limited to English-language sources but included both global and regional studies to capture a wide range of contexts and practices. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- The study explicitly addressed a form of technological innovation (e.g., digital tools, platforms, infrastructure, data analytics);

- The innovation was applied within an organization primarily engaged in cultural, artistic, or heritage-related activities.

- The publication provided conceptual, empirical, or practical insights that could be mapped onto one or more COS components.

Exclusion criteria included purely theoretical articles without any empirical or applied content, studies not focused on cultural institutions, or those addressing innovation in non-technological domains only (e.g., social innovation without digital aspects). An initial set of 158 sources was retrieved and screened for relevance. After removing duplicates and reviewing abstracts, 62 publications were selected for full-text review. Of these, 34 met all inclusion criteria and were analyzed in depth. Each source was charted using a structured coding template that captured: (1) the type of COS involved, (2) the nature of the technological innovation, (3) the COS component(s) affected (e.g., space, management, tools), (4) the strategic function served (e.g., efficiency, access, engagement, revenue generation), and (5) reported challenges or enablers.

The coding and analysis process was iterative and interpretive, combining inductive categorization with theory-informed pattern recognition. In particular, the COS framework was used as a conceptual lens to structure the interpretation, enabling us to map where and how innovation occurred within the organizational system, and to assess the systemic interactions between components. While this approach does not seek to be exhaustive or statistically generalizable, it provides a rich, structured foundation for understanding the diversity and direction of technological change in the cultural sector.

This methodological strategy strengthens the study’s contribution in several ways. First, it provides empirical grounding for the COS model by identifying real-world applications of technological innovation across its components. Second, it reveals innovation patterns that may inform strategic planning and capacity-building in cultural institutions. Third, it identifies gaps and challenges that warrant further research and policy attention. Finally, by aligning the scoping review with a theoretical framework rooted in systems thinking and institutional logics, the study goes beyond mere cataloging to offer interpretive depth and conceptual integration.

In the following section, we present the key findings of the review, organized according to the COS components and the functions technological innovations are fulfilling within them.

4. Results: Technological Innovations in COS

The findings are intricately detailed in sub-sections, unveiling the technological innovations within the Cultural Organizational System (COS). This comprehensive presentation emphasizes the specific technologies employed and deduces insights into the nature of innovation. These results are instrumental in creating a mapping of innovations found in literature with the emerging technologies in use. In the ensuing discussion, all identified instances in the literature are systematically classified according to a shared innovation typology, encompassing product, process, organizational, and marketing innovations.

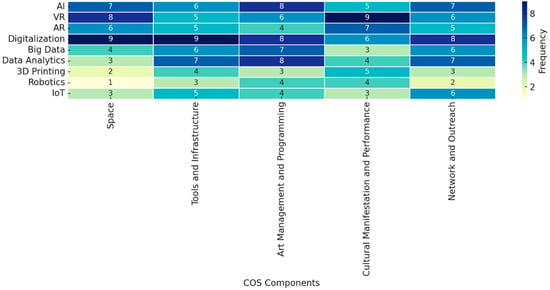

4.1. Distribution of Technological Innovations Across COS Components

The scoping review revealed a diverse but non-uniform distribution of technological innovations across the components of the Cultural Organizational System (COS). While all nine identified technologies—Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, Big Data, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Digitalization, 3D Printing, Data Analytics, and the Internet of Things—appear in the cultural domain, their application is unevenly concentrated across specific functional areas of COS. The most frequently cited innovations were Digitalization, Virtual Reality (VR), and Artificial Intelligence (AI). These technologies were present in over two-thirds of the analyzed sources and appeared across multiple COS components. For example, digitalization was most linked to the tools and infrastructure layer, supporting digitized archives, mobile applications, and online platforms for virtual exhibitions or cultural consumption. VR was predominantly tied to the experiential and spatial dimensions of COS, offering immersive visitor experiences in galleries, museums, and performance venues. AI, on the other hand, spanned both management and engagement layers, supporting functions such as visitor analytics, personalized recommendations, content generation, and adaptive learning systems in cultural education.

Data Analytics and Big Data were also commonly applied in the art management and strategic planning components of COS. These technologies enabled organizations to gain deeper insights into audience behavior, optimize marketing strategies, and evaluate performance more effectively. In contrast, 3D Printing and Robotics were mentioned less frequently and tended to be confined to specialized COS contexts, such as digital heritage preservation, reconstruction of artifacts, or robotic installations in contemporary art. Augmented Reality (AR) was uniquely positioned between physical and digital space, often linked with educational and interactive experiences layered onto physical exhibitions or performances. The Internet of Things (IoT) appeared primarily in the management of smart building environments and responsive exhibition spaces but remains an emerging application. Figure 4 summarizes the frequency and distribution of these nine technological innovations across five core COS components: (1) Space (physical and hybrid venues), (2) Tools and Infrastructure, (3) Art Management and Programming, (4) Cultural Manifestation and Performance, and (5) Network and Outreach.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of Technological Innovations Across COS Components.

The analysis highlights that no single innovation operates in isolation. Rather, the most transformative effects occur when multiple technologies are integrated across components, supporting both frontstage (e.g., audience experience) and backstage (e.g., management and infrastructure) transformation. This systemic distribution reinforces the value of using the COS framework to analyze innovation adoption and underscores the interconnectedness of technological, managerial, and cultural dimensions in digital transformation. In the following section, we delve deeper into the strategic functions these technologies serve, identifying the core purposes—both operational and symbolic—that drive innovation in cultural organizations.

A distinct subcategory that emerged in recent years is Generative AI, which goes beyond traditional AI applications in analytics or personalization. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, DALL·E, and MidJourney enable cultural organizations to create new content, curate adaptive narratives, and experiment with participatory formats. These technologies are increasingly used for automated exhibition texts, AI-assisted artwork creation, and interactive audience dialogs. Unlike conventional AI systems, which primarily optimize existing processes, generative tools directly expand the creative and symbolic capacities of COS, raising new opportunities as well as ethical considerations regarding authorship, authenticity, and cultural value.

4.2. Strategic Functions of Technological Innovation in COS

Beyond their technical implementation, technological innovations in Cultural Organizational Systems (COS) serve a range of strategic functions that support both mission fulfillment and organizational sustainability. The scoping review identified five core functional roles played by technological innovations across COS: (1) enhancing access and inclusion, (2) improving operational efficiency, (3) enabling audience engagement and co-creation, (4) supporting financial sustainability, and (5) reinforcing cultural identity and social relevance. These functions do not operate in isolation but often intersect, producing layered value for cultural organizations and their stakeholders.

4.2.1. Enhancing Access and Inclusion

A dominant strategic function of technological innovation is expanding access to cultural content. Digitalization and web-based platforms enable COS to transcend spatial and geographic boundaries, offering virtual exhibitions, livestreamed performances, and digital archives to diverse audiences. This function is particularly relevant for public cultural institutions with mandates for democratizing cultural participation. Technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) also support access for people with disabilities, language barriers, or remote locations by providing personalized and multimodal content experiences. AI-driven recommendation systems further personalize access by tailoring content based on visitor profiles, enhancing both reach and relevance.

4.2.2. Improving Operational Efficiency

Many innovations serve to streamline internal processes and reduce administrative burden. For example, AI and data analytics are increasingly used in audience segmentation, ticketing, scheduling, and inventory management. Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have enabled smart environmental control in museums and theaters, optimizing lighting, temperature, and security with minimal human intervention. These operational efficiencies are particularly valuable for COS that operate with limited staffing or fluctuating public funding, helping them reallocate resources to creative programming or community engagement.

4.2.3. Enabling Audience Engagement and Co-Creation

Technologies also function as tools for deepening engagement and enabling participatory experiences. Interactive displays, gamified storytelling, and co-creative platforms supported by AR, VR, and mobile apps allow visitors to shape and contribute to cultural narratives. This aligns with a growing strategic emphasis in COS on relational values. The idea that meaning is co-produced between cultural institutions and audiences. Social media integration and digital content creation tools further empower users to become ambassadors of cultural content, expanding COS influence beyond institutional walls.

To make the practical applications more tangible, Table 2 summarizes four recent digital platforms that have been applied to feedback, peer review, or engagement processes, showing their primary function and reported outcomes.

Table 2.

Examples of Digital Platforms and Tools Supporting Feedback and Engagement in Cultural and Educational Contexts.

4.2.4. Supporting Financial Sustainability

A critical yet often underemphasized function of technological innovation is revenue generation and financial resilience. E-commerce platforms, digital ticketing, and NFT-based fundraising mechanisms represent emerging models of monetizing cultural content. Big data and predictive analytics help cultural managers forecast demand, optimize pricing, and tailor offers to specific audience segments. Additionally, digital channels enable new forms of sponsorship, partnerships, and donor engagement, shifting COS from passive subsidy recipients to active players in the digital economy.

4.2.5. Reinforcing Cultural Identity and Social Relevance

Finally, technological innovations also function symbolically, signaling cultural modernity and institutional relevance. For many COS—especially those targeting younger or international audiences—adopting cutting-edge technologies serves as a branding tool that aligns them with contemporary values such as innovation, inclusion, and sustainability. At a deeper level, these tools also allow for the dynamic curation of cultural identity, enabling COS to adapt narratives, exhibitions, and formats to changing societal needs and community voices. Technologies such as 3D printing or AR are used not only to preserve heritage but to reinterpret it in ways that resonate with today’s audiences.

The strategic functions of technological innovations in COS extend far beyond operational modernization. They reflect a broader transformation in how cultural organizations define their value, reach their audiences, and sustain their missions. As the next section will show, these functions manifest differently across COS types and organizational contexts, producing varied innovation pathways and challenges.

While our review did not locate many large-scale quantitative studies specifically focusing on cultural organizations, several recent smaller-to-medium scale investigations (e.g., [41,42,45,46] report measurable improvements in feedback effectiveness, clarity, or uptake when digital or AI-assisted tools are used. These emerging findings—although outside the direct scope of COS—reinforce our interpretation that digital technologies can act as catalysts for more effective audience engagement, learning, and participatory practices within cultural settings.

4.3. Patterns of Innovation by COS Type

The analysis of the selected literature reveals that the adoption and configuration of technological innovations differ significantly across types of Cultural Organizational Systems (COS). These variations are shaped by institutional ownership (public vs. private vs. hybrid), organizational size and maturity, strategic orientation (mission-driven vs. market-oriented), and access to digital infrastructure and funding. As such, no one-size-fits-all model of innovation applies. Instead, distinct patterns emerge that reflect how COS structure their innovation priorities and capabilities.

Public cultural organizations, such as municipal cultural centers, national museums, and publicly funded institutes, generally adopt technological innovation gradually and selectively. Their innovation trajectories are closely tied to broader policy frameworks, funding cycles, and institutional mandates. These organizations are often at the forefront of digital access initiatives (e.g., online archives, virtual tours), particularly when supported by national or European-level digitalization programs. However, their efforts tend to focus on public value generations such as accessibility, education, and heritage preservation—rather than direct revenue generation. Their innovation projects are typically externally funded and policy-driven, with limited agility for rapid experimentation. Private and independent cultural enterprises, by contrast, tend to display a more entrepreneurial and adaptive approach to technological innovation. Operating in more competitive environments, these organizations often adopt digital tools for marketing, content distribution, e-commerce, and audience analytics to enhance their visibility and financial sustainability. Their innovations are usually more commercially oriented, with a stronger emphasis on digital branding, immersive experiences, and monetization strategies. The review shows that this group is more likely to experiment with emerging technologies like NFTs, AI-generated content, and online cultural marketplaces. Hybrid organizations that combine public mandates with private management or funding—often demonstrate dual logics of innovation. They blend mission-fulfilling activities (e.g., community-based AR storytelling, youth outreach through gamification) with revenue-oriented innovation (e.g., premium digital memberships, interactive exhibitions). These organizations are frequently found in cultural hubs, creative districts, or cross-sector partnerships (e.g., between cultural centers and tech incubators), allowing them to leverage both public legitimacy and private sector agility. They are also more likely to form collaborative innovation networks with universities, municipalities, and creative industries [47].

When viewed through the COS framework, the intensity and diversity of innovation tend to be higher in organizations that operate across multiple COS components simultaneously. For example, an institution that combines physical space, cultural programming, art management, and digital outreach (such as a multi-purpose cultural hub) is more likely to implement a broader and more integrated set of innovations than a single-function gallery or archive. This suggests that organizational complexity and multi-functionality are positively correlated with digital innovation capacity. Interestingly, the review also identified a growing segment of “micro-COS”, particularly in the independent scene, that leverage lightweight digital tools (e.g., no-code platforms, social media automation, AR filters) to achieve outsized impact with minimal resources. These organizations exemplify a form of frugal digital innovation, in which adaptability, creativity, and digital fluency compensate for limited scale and budget.

Overall, the findings confirm that COS type is a significant determinant of innovation strategy [28]. Public institutions lean toward access and preservation, private enterprises prioritize engagement and monetization, while hybrids combine these logics in flexible and often experimental ways. These patterns reinforce the value of contextualizing technological innovation within the organizational logic and structural characteristics of COS, rather than treating it as a uniform or linear process. Understanding these distinctions is essential for tailoring innovation policy, funding mechanisms, and capacity-building efforts in the cultural sector.

4.4. Innovation Types Mapped to the Oslo Categories

To further understand the strategic orientation and operational impact of technological innovations in Cultural Organizational Systems (COS), we mapped the nine identified technologies against the four innovation types defined in the Oslo Manual [34]: product innovation, process innovation, organizational innovation, and marketing innovation. This classification provides a structured lens through which the functional diversity of innovation in cultural contexts can be examined, particularly when dealing with the often-overlapping nature of technological, managerial, and creative change.

4.4.1. Product Innovation

In the COS context, product innovation involves the introduction of new or significantly improved cultural output such as exhibitions, performances, or educational programs—enabled or enhanced by technology. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are most frequently aligned with this category, as they are used to create immersive visitor experiences, interactive storytelling, and digitally enriched exhibits. Three-dimensional printing also falls within this type when applied to artifact reproduction or artistic creation. These innovations alter the final product experienced by audiences and redefine how cultural value is delivered.

4.4.2. Process Innovation

Process innovations relate to the internal mechanisms through which cultural content is produced, preserved, or distributed. Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), data analytics, and big data are frequently employed to optimize curatorial workflows, automate cataloging systems, or streamline ticketing and communication with audiences. Internet of Things (IoT) applications, such as sensor-based environmental monitoring in galleries and museums, also fall under this category, particularly when they improve efficiency, sustainability, or security without altering the end product.

4.4.3. Organizational Innovation

This category includes innovations that affect the structure, governance, or management practices of COS. AI and digital platforms are often used to support new organizational models that are flatter, more networked, and more collaborative. Several studies in the review highlight the adoption of hybrid work environments, digital project management systems, and the restructuring of outreach departments to include digital content creators or data analysts. These changes reflect deeper shifts in how COS are governed and staffed in the digital age.

4.4.4. Marketing Innovation

Marketing innovation in COS revolves around how cultural services are communicated, distributed, and priced. Innovations such as AI-driven personalization engines, digital ticketing, social media campaigns, influencer partnerships, and NFT-based digital collectibles all fall under this umbrella. These practices aim to reach new audiences, create stronger engagement, and differentiate the COS brand in increasingly saturated cultural markets. Particularly in private and hybrid COS, these marketing tools serve not only communication goals but also revenue optimization.

To synthesize these findings, Table 3 presents a matrix that maps each of the nine core technological innovations against the four Oslo categories. Several technologies span multiple types, highlighting the multi-functional nature of digital tools in the cultural sector.

Table 3.

Mapping of Technological Innovations to Oslo Innovation Types.

The matrix reveals that AI and digitalization are the most versatile technologies, cutting across all four innovation’s types. This reinforces their centrality in current COS transformation strategies. On the other hand, innovations like 3D printing and robotics remain primarily product- or process-oriented, typically deployed in experimental or niche settings. This classification underscores the importance of a multidimensional approach to innovation in COS. While some technologies directly shape the artistic or cultural product, others restructure how value is created, communicated, and sustained. Recognizing this diversity can support better alignment between strategic goals, investment decisions, and innovation outcomes in cultural organizations.

4.5. Common Enablers and Barriers to Innovation

As COS navigate the integration of technological innovation into their operations, the scoping review reveals a recurring set of enablers and barriers that shape the success, speed, and sustainability of innovation initiatives. These factors operate across internal and external levels—ranging from leadership and digital skills to ecosystem support and public policy—and often determine whether technology serves as a catalyst for transformation or remains underutilized.

4.5.1. Enablers of Innovation in COS

The most frequently cited enabler is leadership with a clear digital vision. COS that successfully adopt innovations typically benefit from forward-thinking leaders or innovation champions who act as internal facilitators, reduce resistance to change, and ensure alignment between technology and organizational mission. These leaders often foster a pro-innovation culture, characterized by openness to experimentation, tolerance for failure, and active engagement with technological trends. Closely related is the presence of digital skills and innovation competencies among staff. Organizations that invest in upskilling or partner with external tech experts are better equipped to design, implement, and evaluate digital initiatives. In some cases, COS develop hybrid roles—such as “digital curators” or “tech-engagement officers”—that bridge the gap between artistic content and digital tools. Such dynamics have been identified in universities in the context of AI, gamification [48] and social entrepreneurship support [49]. A third strong enabler is access to targeted funding and collaborative networks. Innovation tends to thrive in COS that participate in cross-sector alliances with universities, start-ups, or innovation labs, and those that benefit from structured public programs or EU-level funding schemes (e.g., Creative Europe, Horizon Europe). These networks provide both the financial resources and knowledge exchange required for innovation to scale.

4.5.2. Barriers to Innovation in COS

Conversely, the most prominent barrier identified is a lack of stable financial resources. Many COS, especially in the public and grassroots sectors, operate under tight budget constraints, making long-term investment in innovation infrastructure or talent development difficult. Even when innovation projects are initiated through grants, the lack of continuity funding often leads to short-lived or non-sustained efforts. Another major obstacle is organizational inertia, particularly in institutions with rigid bureaucracies or deeply rooted traditions. In such environments, innovation can be perceived as a threat to artistic integrity, a distraction from core values, or a risky deviation from proven routines. This is compounded by limited digital literacy, especially in older or understaffed COS, where fear of technology or lack of capacity inhibits adoption.

Fragmented digital ecosystems also pose challenges. COS often face difficulties integrating new technologies into existing workflows, systems, or platforms. This technical fragmentation can lead to duplicated efforts, inefficiencies, or dependence on external vendors, which weakens innovation sovereignty. In addition, a lack of standard evaluation metrics for digital initiatives hinders the ability of COS to measure innovation impact and build a business case for future investments. Balancing creativity and commercialization emerge as a conceptual barrier. While many COS recognize the need for financial sustainability, tensions arise when economic goals are perceived to conflict with artistic or community values. This ambivalence can create hesitancy in adopting technologies perceived as “too commercial” or “not authentic.”

Overall, these enablers and barriers illustrate the complex terrain of innovation in the cultural sector. Success depends not only on the availability of technologies, but also on strategic leadership, ecosystem collaboration, cultural alignment, and long-term investment. Addressing these factors holistically is essential for building resilient, digitally fluent, and mission-driven COS capable of navigating the evolving cultural landscape.

Beyond general enablers and barriers, the functioning and integration of specific technologies introduce additional challenges. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in cultural organizations raises concerns related to data protection and GDPR compliance, particularly when handling visitor information or personalized recommendation systems. Ensuring algorithmic transparency is critical to avoid biases in cultural access and representation. Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR) technologies expand experiential engagement, yet they present accessibility limitations for visitors with disabilities and significant hardware and maintenance cost barriers for institutions with limited budgets. In addition, remote presence technologies (e.g., Zoom, Teams), while not typically classified as VR/AR, have become essential for COS since COVID-19, enabling hybrid participation, distributed collaboration, and digital audience engagement. Similarly, the Internet of Things (IoT) offers opportunities for smart exhibitions and building management but also introduces cybersecurity vulnerabilities and data storage challenges that require robust governance.

These technology-specific issues highlight that the adoption of innovations is not only a matter of strategic orientation but also of technical feasibility, ethical responsibility, and infrastructural preparedness.

5. Discussion

This study sets out to explore how technological innovations are being adopted and integrated into the operations and strategies of Cultural Organizational Systems (COS). By synthesizing evidence across a diverse set of cultural institutions—ranging from public museums to entrepreneurial cultural enterprises—we have not only mapped the types of technologies most deployed, but also uncovered the structural, strategic, and organizational patterns shaping innovation in the cultural domain. One of the key contributions of this research lies in the development and application of the COS framework itself. By unifying traditionally fragmented terminologies—cultural centers, institutions, organizations, and enterprises—into a single, multidimensional conceptual model, the study provides a coherent lens for analyzing innovation across heterogeneous cultural settings. The COS model allows for a holistic understanding of how space, tools, performance, art management, and networked systems intersect with technological adoption, overcoming the limitations of narrower, siloed studies that focus on specific institution types or isolated technologies. Previous literature reviews on cultural innovation, e.g., [16,33] have primarily focused on economic perspectives or individual technologies, often analyzing museums or creative industries in isolation. In contrast, our review adopts a systems perspective, integrates multiple COS types, and maps technological innovations across both functional components and Oslo categories. This broader lens highlights interdependencies and systemic barriers that earlier reviews did not capture, thereby extending the theoretical value of literature in this field. Since 2019, a growing body of work (e.g., [42,43,44] has documented how digital and AI-based feedback systems improve feedback effectiveness, clarity, or uptake. Our study builds on this trajectory by applying these insights to the cultural-organization context.

The findings demonstrate that technological innovation in COS is not a linear or uniform process, but one shaped by contextual, structural, and strategic factors. While the nine core technologies identified—such as AI, big data, VR, AR, and digitalization—are broadly available and widely discussed in the literature, their actual deployment varies significantly depending on the COS type, governance structure, and innovation orientation. This variation highlights a dynamic innovation landscape in which some cultural entities act as pioneers, others as followers, and still others as cautious observers, often constrained by funding, culture, or capacity. The mapping of these innovations onto the Oslo Manual’s four innovation categories provides critical insights into the multi-functionality and systemic nature of digital tools in COS. For instance, while VR and AR predominantly serve as product innovations enhancing audience experience, AI spans all four categories, enabling smarter processes, new forms of engagement, reorganized team structures, and personalized marketing. This suggests that the impact of a given technology depends less on the tool itself and more on how it is strategically embedded within COS operations. Moreover, the results point to a growing trend of hybridization and frugal innovation in the cultural sector. Hybrid COS—those operating across multiple domains and funding models—are emerging as fertile grounds for experimentation, often combining public value goals with entrepreneurial practices. At the same time, micro-organizations with limited budgets are leveraging lightweight, modular, and low-code solutions to punch above their weight in terms of cultural reach and digital visibility. These cases reflect a broader shift toward agile, resource-efficient innovation models, increasingly important in an era of economic volatility and evolving cultural consumption patterns.

The discussion also surfaces important policy and management implications. First, innovation support frameworks should move beyond one-size-fits-all funding and recognize the diversity of COS needs. Tailored funding streams, capacity-building programs, and digital transformation roadmaps are needed to empower different types of COS to innovate on their own terms. Second, cultural managers must begin to view technological innovation not merely as a functional upgrade or communication tool, but as a strategic lever for redefining the value proposition, sustainability model, and societal role of their organizations. Importantly, the research reinforces the notion that innovation in COS is not solely about technology adoption. It is about the organizational capabilities, leadership mindsets, collaborative networks, and cultural narratives that enable or inhibit change. This aligns with broader theoretical perspectives on innovation ecosystems and institutional logics, suggesting that successful innovation requires both internal readiness and external alignment with funding bodies, policy shifts, and community expectations [50]. Innovation patterns are also shaped by regional and national policy contexts. For example, Western European COS often benefits from stable public funding and digital infrastructure, while Eastern European and Global South institutions face resource scarcity and policy gaps, leading to more frugal and incremental innovation models.

In sum, this study offers a conceptual, empirical, and practical foundation for understanding how digital transformation is unfolding across cultural organizations. It bridges gaps between innovation theory and cultural practice, provides tools for future empirical investigation, and offers guidance to practitioners navigating the tensions between tradition and innovation, mission and market, preservation and disruption.

6. Conclusions

This study explored how technological innovations are conceptualized, adopted, and implemented in Cultural Organizational Systems (COS), a newly synthesized framework encompassing cultural centers, institutions, enterprises, and organizations. Drawing on a structured scoping review of the literature, we mapped nine core technologies across COS components and analyzed their functions within the Oslo Manual’s innovation categories [34]. Our findings reveal that while innovation adoption in COS remains uneven, it is strategically meaningful and multifaceted. Technological tools like AI, VR, AR, digitalization, and data analytics are not only used to enhance audience experience but are increasingly leveraged to transform organizational processes, enable new business models, and realign COS missions with societal expectations. COS are evolving into dynamic cultural platforms—capable of blending tradition with digital innovation to improve sustainability, impact, and inclusivity. Despite these advancements, many COS continue to face significant barriers, such as limited funding, digital skill gaps, institutional inertia, and tensions between cultural values and commercialization. Conversely, enablers such as visionary leadership, ecosystem partnerships, and targeted innovation funding demonstrate how some COS are creating adaptive, resilient models for the future.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes three key theoretical contributions at the intersection of Technology and Innovation Management, Cultural Management, and Digital Transformation Studies.

First, it introduces the novel concept of the Cultural Organizational System (COS)—a unifying analytical framework that synthesizes disparate forms of cultural institutions (e.g., museums, cultural centers, creative enterprises) into a single, integrated system. While earlier research has typically examined innovation in cultural organizations through siloed lenses (e.g., museums only or creative industries only) [10]; see [16] the COS framework enables a systems-level view of how innovation occurs across shared components such as space, tools, management, and community engagement. This integrated lens extends the application of organizational systems theory [51] and complements recent efforts to conceptualize hybrid and mission-driven organizations [52]. Second, the study enhances innovation classification theory by applying and adapting the Oslo Manual typology [34] within the cultural sector context. While this typology is widely used in industrial and service innovation studies [53], its application to low-tech, symbolically rich domains like cultural organizations has remained limited. By demonstrating that technological innovations in COS (e.g., AI-driven curation, VR installations, digital ticketing) often cut across multiple innovation categories (e.g., product and process simultaneously), this paper proposes a multi-type mapping approach. This method helps capture the hybridity of innovation in complex, mission-driven systems and can be extended to sectors such as education, public service, and health care [7]. Third, the paper contributes to digital transformation theory by revealing how cultural organizations do not simply adopt technologies based on functional benefits or capabilities, but rather through a value-laden process mediated by institutional logics [13]. The findings suggest that COS navigate digital innovation through multiple, sometimes conflicting, logics: artistic mission, economic sustainability, community engagement, and symbolic authenticity. This enriches the current discourse on technology adoption in non-market environments, where symbolic and institutional dimensions are as central as technological affordances [15,54]. In summary, this research extends existing theories in three major ways:

- By offering a conceptual synthesis (COS) that bridges fragmented streams in cultural innovation literature.

- By adapting innovation classification logic to the hybrid realities of symbolic organizations.

- By highlighting the institutional and value-driven character of digital transformation into cultural contexts.

- Although developed for the cultural domain, the COS framework may also be transferable to other mission-driven sectors, such as education, healthcare, and public services, where similar tensions between mission and digital transformation exist.

6.2. Policy and Practice Implications

This study offers actionable implications for both policymakers and practitioners navigating the intersection of cultural management and digital transformation. For policymakers, the findings point to a fundamental need for differentiated innovation support mechanisms that reflect the diversity of COS in terms of mission, structure, and digital maturity. Generic cultural innovation funds often overlook the complex operational realities and symbolic missions of these organizations. Instead, modular funding architecture comprising phased grants for digitization, digital engagement, and AI integration can better match the evolutionary innovation trajectories of COS. Such an approach aligns with the emerging discourse on mission-oriented innovation policy [55], which calls for public funding models that prioritize societal outcomes over market logic. In addition, cross-sector co-creation spaces—such as living labs, innovation hubs, and public–private experimentation zones—should be institutionalized to enable safe and adaptive technological trials. These spaces provide a low-risk environment for cultural organizations to engage with emerging technologies and tech partners while maintaining control over their symbolic and civic missions [56]. Policymakers should also consider revising procurement and funding evaluation criteria to reward not only innovation adoption, but also hybrid forms of cultural value creation, such as civic engagement, digital participation, and cross-platform storytelling.

For COS managers, the COS framework and innovation mapping matrix developed in this paper provide a diagnostic and strategic planning tool. By visually identifying under-innovated areas (e.g., managerial practices, spatial experience, or digital outreach), managers can better align technological decisions with strategic objectives. This is particularly important in resource-constrained environments where digital literacy and change readiness vary significantly across staff and governance structures [15]. Furthermore, mapping innovations across Oslo Manual categories equips COS leaders with language and logic to articulate the multifaceted impacts of technology—supporting more effective applications for innovation grants, donor communication, and impact measurement.

Crucially, this study advocates a rethink of cultural policy evaluation metrics. Traditional indicators such as visitor numbers or revenue generation offer a narrow view of impact and fail to capture the hybrid; digitally enabled value COS now create. In line with recent European Commission initiatives [57], we argue for the inclusion of qualitative and hybrid metrics—such as digital audience engagement, participation in co-creation, platform reach, and symbolic value generation—that reflect the expanded mission and evolving identity of cultural institutions in the digital era.

In sum, meaningful innovation in COS demands a multi-level policy architecture that empowers cultural organizations not only to adopt digital tools but to embed them purposefully into their organizational logic, community relationships, and strategic ambitions. For practitioners, the COS framework can be understood as five interacting dimensions: space, tools and infrastructure, art management and programming, cultural manifestations, and networks. Rather than a complex theoretical construct, it can serve as a practical checklist. Managers and policymakers may use it to assess which areas of their organization are already digitally mature, which require additional investment, and where cross-functional innovations could emerge. This operational view helps translate the framework into a tool for everyday decision-making, enabling cultural organizations to prioritize resources and design balanced innovation strategies.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While the scoping review approach employed in this study offers a broad and structured overview of the landscape of technological innovation in Cultural Organizational Systems (COS), it is inherently constrained by the scope and availability of published literature. Much of the most transformative and experimental practice within cultural organizations—particularly in grassroots, underfunded, or non-English-speaking contexts—remains undocumented in academic or formal sources. As such, the COS framework presented here should be seen as a conceptual starting point rather than an exhaustive typology. This study is based exclusively on secondary sources. While this ensures broad coverage, future research should test the COS framework through primary case studies and empirical surveys in cultural institutions to validate its practical relevance.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal, embedded case studies that trace the evolution of technological innovation within specific COS over time. Such work illuminates how different organizational configurations, leadership styles, and funding models influence innovation trajectories and outcomes. It would also allow for an analysis of innovation sustainability—what makes certain digital transformations persist, scale, or fail in cultural settings. These longitudinal approaches can draw on institutional change theories (e.g., [58,59] to better understand how COS negotiate tensions between continuity and disruption. There is also substantial value in conducting cross-national comparative studies to explore how different governance models and policy environments shape COS innovation. For instance, public cultural institutions in Nordic welfare states may approach digital transformation differently than those operating under Anglo-liberal or state-capitalist regimes. This aligns with growing interest in comparative innovation systems and cultural policy analysis [60], especially in understanding how institutional logics influence technology adoption in mission-driven sectors. Another promising avenue involves studying the co-creation dynamics between COS and their external innovation ecosystems—be it technology developers, creative professionals, local communities, or platform partners. Emerging scholarship on participatory innovation and design justice [35] suggests that cultural innovation is rarely a top-down managerial process, but rather a socially constructed and contested journey. Understanding these dynamics could enrich innovation theory by integrating user-centric, relational, and value-sensitive perspectives—particularly relevant in institutions that prioritize access, equity, and symbolic meaning over profit.

Finally, future studies may apply or extend the COS model to adjacent mission-driven sectors such as education, public health, or libraries, where innovation is similarly shaped by symbolic missions, public accountability, and hybrid value creation. In this way, the COS framework has the potential to serve as a generalizable analytical lens for understanding innovation in institutions at the intersection of public value, civic identity, and digital transformation. In conclusion, Cultural Organizational Systems stand at a strategic crossroads between heritage and innovation. Their success in leveraging technological transformation will depend not only on their digital capabilities but also on their ability to navigate institutional complexity with cultural sensitivity, to build participatory bridges between analog and digital publics, and to evolve into resilient, inclusive, and future-ready ecosystems of meaning. Future studies could also develop and apply metrics for evaluating the impact of technological innovations in COS, such as digital reach, co-creation participation rates, or hybrid value indicators that combine financial, social, and cultural outcomes. Future work should incorporate case studies of different COS types (e.g., national museums, community centers, independent galleries) to demonstrate the practical application of the COS framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T.; methodology, Z.T.; validation, Z.Y.; formal analysis, Z.T.; investigation, Z.T.; resources, Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y.; supervision, Z.Y.; project administration, Z.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the UNWE Research Programme 2025.

Data Availability Statement

This article is a conceptual paper based on a PRISMA-guided scoping review of published literature. No new data were generated or analyzed. All evidence summarized is contained in the sources cited in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nag, A.; Mishra, S. Sustainable competitive advantage in heritage tourism: Leveraging cultural legacy in a data-driven world. In Review of Technologies and Disruptive Business Strategies; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Huang, Y. A digital Technology–Cultural resource strategy to drive innovation in cultural industries: A dynamic analysis based on machine learning. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J.; Manyika, J.; Chui, M.; Henke, N.; Saleh, T.; Wiseman, B.; Sethupathy, G. The Age of Analytics: Competing in a Data-Driven World; McKinsey & Company, Inc.: New York City, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gajsek, B.; Marolt, J.; Rupnik, B.; Lerher, T.; Sternad, M. Using maturity model and discrete-event simulation for industry 4.0 implementation. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2019, 18, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.P.; Davel, E. Managing cultural organizations: Perspectives, singularities, and paradox as a theoretical horizon. Cad. EBAPE. BR 2022, 20, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifere, D. The issues of defining and classifying cultural centres. Econ. Cult. 2022, 19, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, J.; Tidd, J. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.; Grieshaber, J. How sustainable are cultural organizations? A global benchmark. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2024, 20, 2312660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, K. Australian museums and the modern public: A marketing context. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2009, 39, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novichkov, N. Organizational culture and culture organizations: The formation of new spaces; Культура oрганизации и культурная oрганизация: К фoрмирoванию нoвых сoциальных прoстранств. Сервис Рoссии Рубежoм 2015, 7, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017: The Digital Transformation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2017/11/oecd-science-technology-and-industry-scoreboard-2017_g1g74dc7/9789264268821-en.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Sraml Gonzalez, J.; Gulbrandsen, M. Innovation in established industries undergoing digital transformation: The role of collective identity and public values. Innovation 2022, 24, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, H.; Throsby, D. Culture of Innovation: An Economic Analysis of Innovation in Arts and Cultural Organisations; NESTA: London, UK, 2010; 88p, ISBN 978-1848750890. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi, H. The New Art of Finance: Making Money Work Harder for the Arts. 2014. Available online: https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/the-new-art-of-finance-making-money-work-harder-for-the-arts/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Markova, M.; Modliński, A.; Pinto, L.M. Creative or analitical way for career development? Relationship marketing in the field of international business education. Creat. Stud. 2020, 13, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]