Abstract

Cosmetics companies are increasingly integrating augmented reality and artificial intelligence technologies into products and services referred to as beauty tech; consumer perceptions of these solutions, however, remain understudied. Data generated via an online survey are implemented in a stimulus–organism–response framework, deduced from the beauty tech literature. Thereupon, the study identifies how interactivity, informativeness, personalization, and service quality of digital and physical beauty tech solutions for home use affect utilitarian and hedonistic values and the perceived risk factors among consumers. Via customer satisfaction, the effect of the value perception on the purchase intention and loyalty is considered. Results hint at strong effects of characteristics of the services and applications on the utilitarian and the hedonistic dimension of customer experience, which in turn strongly influence customer satisfaction. Perceived risk factors play only a marginal role. Only regarding the tested physical product does higher service quality add to the customer experience. Customer satisfaction in turn results in positive brand perception across different stages of the customer journey and leads to a higher purchase intention, positive brand advocacy, and a higher re-purchase intention. Consequently, well-designed solutions can generate higher customer satisfaction and loyalty on multiple stages along the customer journey.

1. Introduction

The leading omnichannel provider for premium beauty in Europe, DOUGLAS, achieved an increase in sales of almost 50% in the fourth quarter of the 2020/2021 financial year. Sales in the third quarter of 2022 rose by a further 5.3%. This means that sales have more than doubled compared to the pre-coronavirus level [1].

In 2022, global sales in the cosmetics market will amount to around USD 430 billion. In their report, State of Fashion: Beauty, the Business of Fashion and McKinsey & Company forecast average global sales growth of 6% per year until 2027 [2].

Although the majority of consumers shop in physical stores, e-commerce is the fastest-growing sales channel for beauty products, with a compound annual growth rate of 12% by 2027 [2]. Online retail in the beauty industry was considered a growth driver, particularly during the COVID-19 lockdown. Douglas, a leading German cosmetics company, more than doubled its sales compared to pre-lockdown levels with an increase of around 55% [1]. According to the market research agency Mintel, the increasing popularity of e-commerce is one of the beauty trends in Germany. The company mentions that digital tools for testing cosmetic products are an important success factor in online retail, especially for younger target groups. The seamless consumer takes center stage here. This is an evolved hybrid consumer who is becoming increasingly flexible thanks to artificial intelligence (AI) and growing virtualization, and acts based on situational needs. They are characterized by individuality and uniqueness and are inspired by personalized solutions, skin screenings, and AI [3].

Cosmetics companies’ focus on the use of augmented reality (AR) and AI has increased significantly due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic [4]. Creating personalized and immersive customer experiences is now essential for companies to retain existing customers and potential new customers in the long term [5]. According to CitrusBits Inc., the use of AR in the sense of virtual try-ons can not only lead to an improved shopping experience, but also to an increase in brand loyalty. Indeed, 70% of consumers surveyed show increased brand loyalty when their shopping experience is improved by AR technology [6].

Many online shops are now working with AR services to offer consumers the option of virtual try-on (VTO) [7,8]. AI technology also goes one step further. It is used in the cosmetics industry to provide customers with personalized recommendations based on their skin or hair needs using digital diagnostic tools [5]. It also makes it possible to create personalized products, such as the desired lipstick color, using an app in combination with a physical device [9].

The integration of AI into physical devices opens up new possibilities, especially for people with limited arm mobility: Around 50 million people worldwide have impaired fine motor skills, which makes applying cosmetics an everyday challenge [10]. Beauty tech solutions aim to make the industry more inclusive and diverse, as well as more responsible [11].

Beauty tech solutions from cosmetics companies and brands are usually brought to market in collaboration with external technology providers. The two largest players specializing in the use of AR and AI-based solutions and used by international cosmetics companies and brands are ModiFace and Perfect Corp. According to the market research company InsightAce Analytic, cosmetics brands spent around USD 2.7 billion on AI technology in 2021. Spending is expected to rise to USD 13 billion by 2030 [12]. This suggests that the beauty tech market is a market with a lot of growth potential.

Across all markets, sales of just under USD 3.8 billion in 2021 were attributable to purchases triggered by beauty tech apps. This figure is expected to more than double by 2026, growing at an average growth rate of just under 19%. This means that sales of beauty tech solutions could account for around 3% of the entire cosmetics market by 2026 [13].

In Europe, the French cosmetics group L’Oréal is the driving force behind the digitalization of the cosmetics market [14], with a total turnover of EUR 41 billion. In 2018, the Canadian startup ModiFace, which is based on AR and AI technology, was acquired. L’Oréal currently offers 25 digital services based on ModiFace’s AR technology alone [15]. In comparison to ModiFace, with its focus on digital AI and AR-based solutions, its competitor Perfect Corp. specializes in technology solutions for the beauty and fashion industry. The young company is backed by international investors such as Alibaba, Goldman Sachs, Snap, and Chanel with USD 130 million and already counts 17 of the world’s 20 largest beauty companies among its customers [12].

The German beauty tech market is still underdeveloped, and with a turnover of USD 130 million in 2021, it is forecast to grow to almost USD 340 million in 2026.

Beauty tech solutions aim to address customers in a more personalized and targeted way. From a business perspective, it can be postulated that AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions aim to improve the customer experience (CX) along the customer journey (CJ) [12]. For example, countless cosmetics brands have already benefited from a significantly higher conversion rate, higher website traffic, or a longer time spent on the website when using digital services such as the VTO [16]. The aim of digital services is to make it easier for users to make purchasing decisions in e-commerce. Before the use of digital beauty tech solutions, consumers were able to obtain information about a product online but were forced to seek further advice from sales staff in a bricks-and-mortar shop. Furthermore, users can test far more products virtually before making a purchase than would realistically be the case offline.

If physical devices are considered, one intention is particularly in focus: to bind customers to the brand in the long term. In terms of sustainability, returns of cosmetic products can also be reduced [17]. Furthermore, by using beauty tech, cosmetics companies are aiming to make the industry more diverse and inclusive. Accessibility is the focus here. The fact is that there are currently only a few solutions for people with disabilities on the beauty market. AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions make it easier to apply cosmetics, for example, through voice assistants that give makeup and touch-up tips in real time or through physical devices [18,19].

Summarizing, beauty tech can be defined as an intersection between beauty and technology, including products, appliances, and software solutions that use modern technologies to improve skin care, cosmetics, hair care, and overall well-being [20]. It can be categorized as follows:

- Digital services, e.g.,

- ○

- Virtual try-ons

- ○

- AR Filter

- ○

- Color-tone finder

- ○

- AI-based consultation and recommendations

- Physical appliances, e.g.,

- ○

- Wearables

- ○

- Home appliances

- ○

- Easy application

- Accessibility appliances

Through personalized solutions for all, beauty tech can go some way to making the cosmetics industry more sustainable via reduced overconsumption through customized products. Far too often, consumers choose the wrong products, such as the wrong color or formula for their skin type.

It is true that cosmetics companies are already increasingly using AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions and shifting the purchase decision phase of discovery and trial to e-commerce. However, some consumers still find filters or VTOs too artificial. This can potentially lead to frustration and dissatisfaction, which can ultimately have a negative impact on the customer experience [21].

Although a few studies have already looked at the use of technologies such as AR and AI in the cosmetics industry, see Table 1, they restrict themselves to one of the technologies and only depict parts of the customer journey (CJ). They also focus predominantly on digital solutions such as VTO [8] or diagnostic and consulting tools, i.e., chatbot-like applications. Physical beauty tech devices for home use are not analyzed.

The primary aim of this study is therefore to take a holistic view by analyzing and evaluating comparatively the impact of AR and AI on customer experience in the cosmetics industry. It analyzes how AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions influence the individual CJ phases. It thus answers the question whether the observed solutions strengthen customer loyalty and brand loyalty, i.e., lead to positive word-of-mouth (WoM).

As detailed in the following section, several studies already considered comparable objectives. This study differentiates itself from the existing literature in three distinct ways.

First, as compared to the existing literature, which only focuses on AI and AR solutions separately, this study provides a comparison of both types of solutions in the context of the same comprehensive research model, allowing for a higher degree of comparability of the results.

Second, by considering the Rouge Sur Mesure by YSL Beauty for the first time, a physical beauty tech product is considered.

Finally, the implemented model combines for the first time hedonistic and utilitarian benefits via the customer experience with customer satisfaction and their joint effect on different stages of the customer journey, i.e., in particular, purchase intention and customer loyalty.

For practitioners from the cosmetics industry, this study provides first comparative insights into the role that digital AI and AR solutions play in developing customer satisfaction and loyalty. It delivers to them an overview of which aspects are important in developing brand experience and thus customer satisfaction. Thus, it supports them in developing more effective solutions.

To achieve its objective, the study is divided into five sections. Following a synopsis of the relevant literature to deduce the central research objective, detailed research hypotheses are developed and summarized in a comprehensive research model. The fourth section presents the data set used, estimates the model developed in the third section, and discusses the results against the background of the existing literature. The study concludes with a discussion of practical recommendations and limitations.

2. Literature Review

The focus of this paper is on the interaction between the following topics: beauty tech solutions based on the technologies of AR and AI, and CX and CJ.

Considering the empirical exploration of beauty tech in connection with CX and the three superordinate CJ phases, it can be stated that this does not exist in either German-speaking or English-speaking countries. Although the importance of AR and AI in the cosmetics industry is emphasized in some publications, these are not empirical studies.

Scientific publications that deal with the use of AR and AI in the cosmetics industry only focus on one of the two technologies, with AR predominantly being analyzed using VTO solutions. Riar et al. [22] confirm in their literature review that AR is mainly considered an equivalent to VTO. As virtual fitting rooms and product visualizations are not only used in the cosmetics industry, but also in other sectors such as the fashion or furniture industry, these papers were also considered if they covered at least parts of the CX or CJ.

In addition, individual papers looked at different industries regarding AR technologies. For example, the papers by Gabriel et al. [23] and Feng and Xie [24] each referred to both the fashion and beauty industries. The research by Smink et al. [25] looks at the cosmetics and furniture industries, respectively. However, the use of AI in the cosmetics industry was examined regarding AI-based solutions such as digital analysis tools or AI-based questionnaires. Furthermore, industry-independent studies have helped to gain an overview of the relevant constructs used in AR and AI or CX and CJ for operationalization using the S-O-R (stimulus–organism–response) model. Table 1 summarizes the most important findings of the literature research.

Table 1.

Synopsis of articles.

Table 1.

Synopsis of articles.

| Article | Theoretical Model | Method | Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seo and Kwon [26] | PRISMA | Review Study | Use of AR aids purchases of cosmetics via emotional reaction. |

| Voicu et al. [27] | S-O-R | PLS-SEM | Fit confidence impacts utilitarian, hedonistic, and social value as well as innovativeness, immersion. Continued usage intention is impacted by fit confidence and value perceptions. |

| Hapsari et al. [28] | S-O-R/PAD | PLS-SEM | Interactivity and aesthetic quality impact hedonistic value, which impacts WoM. |

| Gabriel et al. [23] | S-O-R | CB-SEM | Interactivity and novelty impact hedonic value, which impacts satisfaction, which impacts continuance and purchase intention. |

| Feng and Xie [24] | PMT | Regression | More privacy concerns lead to negative attitude towards AR applications. |

| Smink et al. [25] | - | ANOVA Mod-Med Regression | AR leads to increased spatial presence, impacting brand response and purchase intention. Personalization impacts behavioral and purchase intention. |

| Riar et al. [22] | - | Review Study | Relevant AR characteristics: interactivity, vividness, sensory feedback, innovativeness, simulated physical control impact usage, purchase, WoM, reuse, revisit intention as well as loyalty and brand engagement. |

| Smink et al. [29] | - | ANOVA Mod-Med Regression | AR increases experience via informativeness and enjoyment, which increases purchase intention and brand attitude. AR is considered intrusive but without negative consequences. |

| Simay et al. [30] | U and G | SEM | Social media addiction leads to usage and actual purchases. Purchase impacts eWoM intention. |

| Azim Zadegan et al. [31] | - | Correlations | Innovative and qualitative AR via satisfaction impacts purchase and re-purchase intention. |

| Ellis and Dudkina [32] | S-O-R/PAD | Regression | Satisfaction positively impacted by hedonistic value, while hedonistic value impacted by interactivity, informativeness, entertainment, ease of use, aesthetics, and variety. |

| Kanaska [33] | - | Sentiment Analysis | Generation Z more critical about personalization in skin care due to data security concerns. |

| Netscher et al. [34] | TAM | Correlations/t-tests | Age impacts AI use and enjoyment. Image, subjective norms, and ease of use impact acceptance. |

| Hilken et al. [35] | SCT | Mod-Med Regression | Interaction (physical control and environmental embedding) impacts utilitarian and hedonistic value via spatial presence. Decision comfort is impacted by awareness of privacy. |

| Aminesh et al. [36] | S-O-R | Regression | Interactivity impacts sense of telepresence and flow. Flow moderates the impact of interactivity on purchase intention. Sociability impacts social presence. |

| Hoffmann et al. [37] | TAM | ANOVA Regression | Evaluations increase with higher utilitarian and hedonistic value. Interaction of utilitarian and hedonistic value. |

| Ifekanandu et al. [38] | - | SEM | AI has a positive impact on CX. Personalization options impact loyalty. |

| Yin and Qiu [39] | S-O-R | SEM | Accuracy, insight, and interaction of AI impact utilitarian and hedonistic value, which in turn impact purchase intention. |

| Trivedi et al. [40] | (TAM) | PLS-SEM | Motivation to use AR impacts the perceived value and the purchase intention. Involvement mediates the relation. |

| Siagian and Gui [41] | SEM | Interactivity impacts purchase intention via control. System and information quality impact purchase intention via satisfaction. | |

| Micheletto et al. [42] | TAM | SEM | Informativeness impacts behavior, mediated via enjoyment. Moderate levels of enjoyment and ease of use are best. |

| Laberger et al. [43] | TAM | Regression | Usefulness impacts purchase intention, mediated by satisfaction. |

| Kurniawati et al. [44] | SEM | AR does not impact brand experience and customer satisfaction. | |

| Lele and Shaw [45] | ES-QUAL | PLS-SEM | Hedonic motivation and efficacy impact loyalty intention. Perceived value, risks, and system quality have no significant impact. |

S-O-R: Stimulus–Organism–Response Model; TAM: Technology Acceptance Model; PAD: Pleasure Arousal Dominance Model; PMT: Protection Motivation Theory; U and G: Uses and Gratifications Model; SCT: Social Cognitive Theory; SEM: Structural Equations Model; PLS-SEM: Partial Least Squares- Structural Equations Model; CB-SEM: Covariance-based-Structural Equations Model; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; ES-QUAL: Electronic Service Quality Model.

Table 1 indicates that previous research confirms a predominantly positive effect of AR on consumers’ purchasing intentions and behavior. However, there have been no empirical studies to date that have comparatively examined the range of AR- and AI-based solutions (digital and physical) in the beauty industry in terms of CX along the three overarching CJ phases. To date, research into the beauty industry has focused either on AR or AI, with only parts of the CJ being examined in each case, e.g., purchase intention or word-of-mouth. The following research question therefore remains currently unanswered and will be addressed in this study:

RQ

: In what way do AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions influence CX?

The neo-behavioristic S-O-R model [46] is particularly suited for analyzing these relationships. Despite the previous focus on digital services alone, it can be assumed that the model, including its constructs, is also applicable to physical devices. As compared to its predecessor, the S-O-R model includes the organism part, which encompasses characteristics that are inherently bound to the participants and cannot objectively be measured.

Considering the critical role of customer experience and satisfaction in forming a purchase intention [39,41,42], as witnessed from the synopsis that is Table 1, the S-O-R model is particularly suitable.

Of the existing literature, the design adopted by Lele and Shaw [45] most closely resembles a comprehensive approach to linking the three main aspects that resulted from Table 1, that are customer experience, measured via hedonistic and utilitarian motives, customer satisfaction, purchase intention, and customer loyalty. Thus, the ongoing analysis will most closely follow an adjusted version of their designs.

AR and AI solutions positively impact the CX, expressed via the perceived utilitarian and hedonistic value of the solutions. Important characteristics of the solution are interactivity, personalization options, and novelty or innovativeness of the solution. A fourth characteristic, which Siagian and Gui [41] call system quality, here referred to as service quality, summarizes quality issues of the solution, like its accuracy and proper functionality. What Yin and Qiu [39] refer to as insight can also be considered as the informational content of the solution. These characteristics of AR and AI solutions act as external stimuli in the context of the S-O-R model.

They impact the internal perceptions of consumers, expressed in the organism as perceived informational and hedonistic value, which are influenced by risk factors like privacy and security concerns regarding the shared data and subjective norms.

Linking the value perception with the CJ as the response is the customer satisfaction. A positive CX, on a utilitarian as well as a hedonistic level, consequently results in more satisfied consumers. Satisfied consumers, in turn, are more open to purchasing or re-purchasing the product or service and generate positive awareness about them via WoM. Thus, customer satisfaction is added as a mediator between the organism and the response part of the model.

The following section will in detail discuss the distinct linkages between the proposed building blocks of the model and the implemented research hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Deduction of the Research Hypotheses

The way in which consumers inform themselves about products has grown to include the experience factor of the virtual try-on and other AR-based applications [23,25,42]. In addition, physical devices designed especially for people with physical disabilities offer a new experience, as they can now apply makeup independently and confidently. Based on this, the first hypothesis is as follows:

H1.

Beauty tech solutions influence the CX.

Based on the synopsis of the literature, beauty tech solutions can be characterized by their interactivity [28], information content [25], service or system quality [45], and options to personalize [25].

Considering the organism, the CX can be represented via a hedonistic [32] and an utilitarian dimension [27]. Additionally, internal skepticism regarding AR solutions is considered as a risk factor [24]. Thus, in total, twelve sub-hypotheses, H1a through H1k, arise that link the four characteristics and the three parts of the organism.

Both the results of Gabriel et al. [23] and Hsu et al. [47] illustrate that interactive experiences evoke a high level of pleasure among users. According to Gabriel et al. [23], users rate interactivity according to the entertainment value and enjoyment they experience when using such applications, which in turn can increase their involvement. Harris has shown that consumers also enjoy using AR applications such as VTO in practice. According to Patil and Rao [48], personalized recommendations can support customers during the purchasing decision process and thus increase customer satisfaction. In terms of service quality, according to Ashfaq et al. [49] and Nikhashemi et al. [50], system quality can be considered a predictor of satisfaction due to its influence on the user experience. However, this is contradicted by the results of Gabriel et al. [23], who found that AR system quality has no effect on the perceived hedonic benefit of respondents.

According to Kanaska [33], Generation X is concerned that AI-based product recommendations will not be able to achieve efficient and visible results. Services that offer product recommendations from just one brand are also suspected of being geared towards generating more revenue for the company rather than offering serious recommendations. The study also indicates that AI technologies for personalization are used in particular by companies to enter consumer segments that have not yet fully arrived in the mass market.

Offerings on the market are becoming increasingly interchangeable. To gain the attention of customers, companies and brands must create unique CXs that consider the individual needs and expectations of consumers. If a product or service does not meet their expectations, this can have a negative impact on customer satisfaction. This leads to a further hypothesis:

H2.

The CX influences consumer satisfaction.

According to Yin and Qiu [39], the utilitarian benefit, which is characterized in particular by the convenience of AR technology and the improvement in shopping efficiency, can lead to increased consumer satisfaction. The subjective experience of consumption, which is characterized by emotional experiences, plays a particularly important role in customer satisfaction. Vieira et al. [51] also found that hedonistic benefits have a positive influence on satisfaction. According to Ellis and Dudkina [32], there is also a direct link between hedonistic benefits and satisfaction.

Thus, the construct of satisfaction operates as a mediator between the organism and its response because the degree of satisfaction depends on the extent to which the applications meet the expectations, ideas, and needs of consumers.

With two dimensions of the CX and the risk factors, a total of three sub-hypotheses, H2a through H2c, arise.

Previous research has shown that a consumer’s satisfaction is crucial for their purchasing behavior. Ashfaq et al. [49] argue that satisfaction is a reliable influencing factor for purchase intention, brand choice, re-purchase intention, and continuance intention. According to Vieira et al. [51], it also influences consumers’ behavioral intentions. Consequently, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3.

Consumer satisfaction influences the CJ.

This study assumes the CJ model proposed by Lemon and Verhoef [52]. If a consumer develops positive emotions while using AR- and AI-based beauty tech solutions, it can be assumed that the resulting satisfaction will influence the pre-purchase phase of the CJ by recommending it to friends or acquaintances, who in turn will prefer the recommended AR app or physical beauty tech device when evaluating the alternatives (evaluation phase) when a need arises (awareness phase). The literature review revealed that satisfaction is a reliable and good predictor variable for purchasing behavior, including purchase intention [31], brand choice [29], re-purchase intention [31], and continuance intention [22]. For the post-purchase phase, it became clear that satisfaction is also an indicator for further purchases and WoM. This could have an effect on customer retention or loyalty in the case of satisfied customers [38,45].

Consequently, there are five sub-hypotheses, whereas the three parts of the post-purchase phase will be summarized into a single one for the moment, so that sub-hypotheses H3a through H3c result. Based on the empirical results, it will be argued that in the second scenario, H3b has to be split into five sub-hypotheses.

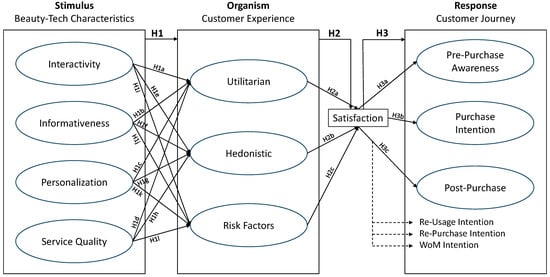

Figure 1 summarizes the three main hypotheses as well as the partial hypotheses resulting from the discussion above into a comprehensive illustration of the underlying research design of this study.

Figure 1.

Research design and hypotheses.

3.2. Survey Implementation and Design

The survey was conceptualized and conducted in early 2024. To assure its validity, a pre-test with five experts and representatives of the target group was conducted. The pre-test allowed to determine a mean processing time of approximately ten minutes, which is later used to filter participants.

The ideal target group of the survey were younger people who are technophiles and have an interest in cosmetics and beauty products; ideally, they are already familiar with new technologies and possess first-hand experience with AR and AI applications, physical or digital. Considering that the survey has been conducted in German and participants are uniformly German, the target group encompasses primarily women. Defining the target in this way not only helps determine the ideal channels to contact potential participants, it also focuses the study and thus its results on the current and future consumers of respective products and services.

According to the set target group, an online survey was conducted, and participants were contacted primarily via social media platforms, i.e., respective interest groups therein. To enhance participation and motivate participants, a raffle with three cosmetics gift vouchers was used.

To make the questionnaire as accessible as possible to participants, the term beauty tech has intentionally been avoided. Instead, after a detailed introduction of the term, artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR) applications have been used as terms throughout the survey.

Permission to use the given answers in the course of scientific studies was gained after informing the participants about the anonymity and confidentiality of the survey.

In the course of the survey, participants were asked to give answers in the context of physical and digital beauty tech solutions. The use of images of the digital service in Scenario 1 as well as the physical product in Scenario 2 has been granted by the respective service provider or producer.

The survey itself has been split into five main parts, containing a total of 33 questions. For all closed numerical questions, a four-point Likert scale has been implemented.

Initially, participants were assured of the anonymity of their answers and their informed consent for the collection and evaluation of the given answers was queried. In the first part of the survey itself, participants were asked about their experience with and perceptions of digital services in the cosmetics industry in general. In the second part, the focus was on physical beauty tech appliances. The objective of both parts can be found in eliciting the existing knowledge about the topic in society and establishing the qualification of the participants to provide valid answers in the context of the two scenarios from parts three and four.

The third and fourth parts of the survey consist of these two scenarios, where a digital tool (Beauty Genius by L’Oréal Paris) and a physical tool (Rouge Sur Mesure by YSL Beauty) are presented to the participants, and they are queried regarding the different aspects of the underlying research model as illustrated by Figure 1.

Since currently no quantitative studies on beauty tech exist that provide suitable scales to be measure the constructs in the context of the S-O-R model, in most cases new scales have to be constructed. Thus, scales of existing studies on the use of AR technologies have been implemented after adjusting them to fit the particular case of beauty tech solutions. Table 2 summarizes the different constructs, the number of used items per construct, as well as those articles from which the respective items or inputs for item generation were taken.

Since some constructs are measured via a single item, the arguments raised by Diamantopoulos et al. [53] in favor of single-item scales can be referred to that depending on the respective context, they can perform equally well as multi-item constructs.

Table 2.

Constructs.

Table 2.

Constructs.

| Construct | Items | Design Based On |

|---|---|---|

| Interactivity | 3 | Hsu et al. [54], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Information Content | 2 | Köcher et al. [55] |

| Personalization | 1 | Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Service Quality | 2 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Nikhashemi et al. [50], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Utilitarian | 1 | Yin and Qiu [39], Voicu et al. [27] |

| Hedonistic | 6 | Voicu et al. [27], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Risk Factors | 1 | Kanaska [33] |

| Satisfaction | 1 | Hsu and Lin [56], Vieira et al. [51] |

| Pre-Purchase—Awareness | 1 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Vieira et al. [51], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Purchase Intention | 6/5 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Vieira et al. [51], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Post-Purchase—Continued Usage Intention | 1 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Vieira et al. [51], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Post-Purchase—Re-Purchase Intention | 1 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Vieira et al. [51], Gabriel et al. [23] |

| Post-Purchase—WoM Intention | 1 | Ashfaq et al. [49], Vieira et al. [51], Gabriel et al. [23] |

Considering that the first scenario represents a digital service and the second a physical product, only in the first scenario the reuse of the offered service is queried. Similarly, the construct for purchase intention consists of different reasons for the purchase and how much the participants agree with them. Since determinants of the purchase intention are inherently different for digital services and physical products, in the first scenario the construct consist of six items, while in the second scenario it consists of five items. The items are different and designed especially for the particular scenarios.

Risk factors are represented by the participants‘ general perception of AR- and AI-based solutions in the way they are discussed in the listed article by Kanaska [33].

The fifth and final part consists of questions about the participants‘ sociodemographic and economic situation. The questionnaire can be found in Appendix A.

During the execution of the survey, the questions for the multi-item constructs were displayed in random order to reduce potential common method bias.

The survey has been approved by the ethics committee of the International School of Management and is listed under number K-2025-JP-07.

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Sample

A purposive sampling approach was adopted to generate the sample. The online survey was disseminated among special interest groups on social media, e.g., in particular on LinkedIn. Concentrating on participants with a stated interest in cosmetics, the suitability for participation has been assured. Communication of the focus of the survey furthermore assured that only those participants took part in the survey that at least have a passing understanding of technologies like AI and AR.

After cleaning the original data set of 204 participants for incomplete questionnaires (50 cases/24.51%) as well as those with answering times outside an acceptable range (11 cases/5.39%), a total of 143 valid cases remained. All of these participants stated a distinct interest in beauty tech. Consequently, a gender distribution of 126 women (88.11%) and 17 men (11.89%) was not surprising, considering that the survey was conducted among the German population.

Thus, the sample is not representative of the whole of the German population, but, lacking detailed numbers, it can be expected to reflect well on the stratum of the population that has an interest in beauty tech applications.

The majority of the participants originate from generation Z (51%) or generation Y (34%), leading to a median age of 26.82 years. Compared to the numbers for the German population, those numbers again are not representative. It can, however, be assumed that particularly younger people, generation Y covering the population until the mid-40s, are distinctly more interested in new technologies and applications. Considering that 46 participants (32%) were still students, this further contributes to the young median age and an interest in the study’s topic.

The strong presence of younger people, students in particular, can also explain the median income in the sample of EUR 1366.20, which lies distinctly below the number for the German population.

Summarizing, the sample does significantly over-represent women and participants from younger generations. Considering the topic of the survey, which has been transparently communicated to the participants already during the process of participant acquisition, the bias comes as no distinct surprise since the sample decently well represents the stratum of society that can be assumed to have a particular interest in beauty tech and cosmetics in a broader sense.

To elicit how well the participants are already familiar with digital services and physical tech products in cosmetics, Table 3 summarizes the share of participants already familiar with the most common applications. For those participants that are familiar with the application, the average familiarity with the type of service (measured on a five-point Likert scale) or product (measured on a three-point Likert scale) is reported as well.

Table 3.

Previous experience with digital services and products.

Finally, in Table 4, descriptives for the implemented constructs are summarized. The first value reports the results for Scenario 1, and the second value, after the slash, the results for Scenario 2.

Table 4.

Descriptives for the constructs.

An important aspect to point out is that in Scenario 2, the participants are less interested in purchasing the product, while at the same time they report a higher level of satisfaction, and while the utilitarian experience is almost the same as well as a better hedonistic experience. With Scenario 2 representing the significantly more expensive physical product, this result does not surprise. It does, however, point out that the two cases are distinctly different in the perception of the participants and thus provide heterogeneous solutions.

4.2. Estimation of the S-O-R Model

Before the estimation of the model, a Harman single-factor test was conducted to test for the presence of a common method bias inherent in the data set. For both scenarios, the largest extracted factor explained decidedly less than 50% of the total variance explained and thus the presence of a common method bias can be rejected.

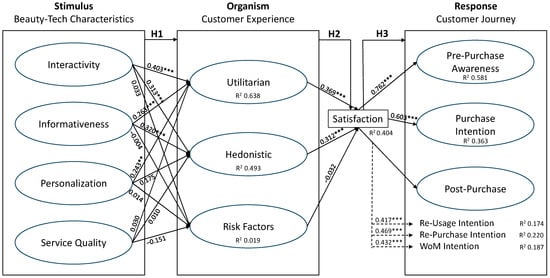

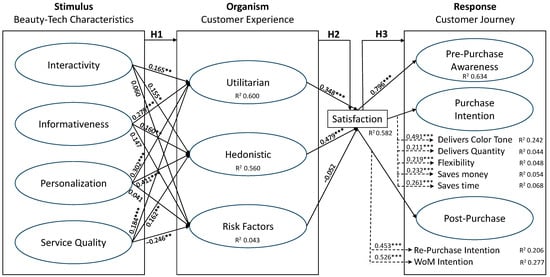

Figure 2 and Figure 3 summarize the estimation results of the model presented in the methodology section. The results are shown separately for the two scenarios.

Figure 2.

Results Scenario 1 - ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Results Scenario 2 - * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Scenario 1: Beauty Genius by L’Oréal Paris

Scenario 2: Rouge Sur Mesure by YSL Beauty

For the estimation of both scenarios, a PLS-SEM estimator has been implemented using the seminr package in R 4.4.2. Comparison of the results of the estimation thus gives insights into whether the results remain stable across different applications or are application-specific.

The arrows report the estimation coefficients as well as their significance levels indicated by asterisks. * indicates significance at the 10% level; ** significance at the 5% level, and *** significance at the 1% level. While a PLS-based analysis precludes the calculation of significance levels, bootstrapping with 1000 repetitions is used to determine means and standard error, based upon which t-values are determined which yield the reported significance levels.

Values below the constructs report coefficients of determinations, indicating how well each of the constructs can be explained by the preceding layer.

To assure construct reliability and validity, for each of the multi-item constructs in the two scenarios, Table 5 reports four quality indicators, i.e., Cronbach’s Alpha, rho A, and rho C (critical value 0.7) as well as the average variance extracted (critical value 0.5).

Table 5.

Construct reliability and validity.

In the second scenario, the indicators for purchase intention were decidedly below the critical thresholds. An exploratory factor analysis revealed that the five items inherently measure different concepts. Thus, the decision has been reached that in the second scenario all five dimensions of the purchase intention are considered separately as single-item constructs.

Similarly, the re-purchase intention reported very low values. Estimating the correlation between the two items reveals that both items are independent of each other. Thus, they too are implemented as separate single-item constructs.

For all remaining constructs, the indicators are well beyond the critical thresholds, and the scales thus are well suited to measure the respective concepts. Only the construct of hedonistic utility and the purchase intention report comparatively low values for the average variance extracted, while still exceeding the critical threshold of 0.5, however.

A comparison of the two scenarios reveals comparable outcomes with three particular differences to be pointed out.

All constructs, except for the risk factors, the dimensions of the post-purchase phase report, and in the second scenario, the dimensions of the purchase intention, report high effect sizes, i.e., R2 statistics of at least 25%. While those are slightly smaller in the first scenario, they still illustrate the overall suitability of the selected research design and the overall quality of the estimation results.

The risk factors, i.e., the adversity using AI and AR solutions, only report small R2 statistics indicating that any existing adversity is not service or product specific but can be considered exogenous to the model.

The figures illustrate the strong effect that perceived service and product characteristics have on the customer experience. It can be noted that the hedonistic dimension reports slightly smaller R2 statistics. Since the study has been conducted as an online survey without the participants being able to test the service or product, hedonistic experiences and advantages become decidedly harder to evaluate. These results conflict with the study by Kurniawati et al. [44], who do not find significant impacts on CX and satisfaction. It is, however, in line with the bulk of the remaining studies.

Turning to the main differences between the two scenarios, in the first one, service quality does not impact any of the dimensions of customer experience. While in the second scenario, it has a significant effect on all three dimensions. Perceived risk factors, however, even in the second scenario, can only weakly be explained.

Conclusively, for the digital service, the service quality seems to play a subordinate role. While this result at first glance might surprise, service quality may be acting as a hygiene factor regarding the customer experience when high-priced services are involved. This result coincides with Lele and Shaw [45], who also found no significant impact on service quality in the context of studying an AR application.

Where in the first scenario, personalization only impacts the utilitarian experience, in the second scenario it has a significant effect on the hedonistic experience as well. Since the prime unique selling point of the product in the second scenario is the personalized provision of lipsticks, these results do not surprise.

Preliminary analysis revealed that the five dimensions of the purchase intention in the second scenario could not be considered as a single multi-item construct. The results in Figure 3 reveal part of the reason for this. Customer satisfaction has a highly significant and quite established impact on the dimension of the product, providing exactly the required need. For the other four dimensions, customer satisfaction still emits a highly significant effect, which, however, only has a weak effect strength.

Both scenarios show consistently positive effects of the four characteristics on both utilitarian and hedonistic benefits, even if not all are significant. Thus, the considered characteristics are important drivers regardless of the context or product, although the exact effects vary.

The insignificant link between service quality and hedonistic benefits in the first scenario is consistent with the studies by Gabriel et al. [23] and Lele and Shaw [45], who, however, use system quality instead of service quality. In their case, system quality only addresses AR in general. The results for the second scenario, where the impact of service quality becomes significant, thus do not fully align. Consequently, the relevance of service quality is case-specific and might be considered a hygiene factor for high-price services.

The overarching hypothesis, H1, is strongly supported by the significant positive correlations between the four characteristics and the CX represented via the organism.

In line with the study by Smink et al. [29], the risk factors appear to be less relevant. Even though they might be independent of the rest of the model, companies should not completely disregard them, as the unrestricted use of AI can potentially lead to, even if unintentional, discriminatory prejudices and practices.

Pricing might be a yet unobserved risk factor that could have a negative impact on the CJ, especially the purchase phase. In theory, it has been shown that beauty tech devices for personalizing products are significantly pricier than conventional products. This means that the use of the device would have to be worthwhile over a long period of time. Despite the participants’ approval, it is clear that for many, the critical upper price limit is already reached at a price of EUR 199. This raises the question of whether physical beauty tech solutions are currently a realistic option in terms of the democratization of personalized solutions. This also applies to people who are already disadvantaged due to health conditions.

Satisfaction, as expected, is strongly and positively influenced by the CX. This coincides with the literature, that both functional and emotional factors are relevant to the development of customer satisfaction [57,58]. In terms of hedonistic benefits, this is consistent with the findings of Gabriel et al. [23]. Positive aspects also have a stronger influence on satisfaction than negative aspects, which are represented by the risk factors. At this point, however, it should be noted that CX and satisfaction are complex constructs, whose interplay has only been simplified here.

In both scenarios, satisfaction has a strong positive effect on various stages of the CJ. Overall, the results thus also support H3, and customer satisfaction provides a decisive link for translating a good CX into a positive CJ.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations for Practitioners

The results emphasize the importance of interaction and information content as the main drivers of perceived utilitarian as well as hedonistic benefits.

This implies the need for companies in the beauty industry to invest in these aspects, as such an investment will most likely lead to an improvement in CX. Both detailed and relevant information about the products and services are important here. While the expansion of information content is a marketing task, the area of interaction possibilities falls under the technical or programming area or product conceptualization. In both cases, the provider has already realized the relevance of the information content and offered a very detailed description of the service or product on their websites.

Personalization options are just as closely linked to the area of product conceptualization. Even if the resulting increase in benefits is not as strong as with the other two characteristics, it is still a significant driving factor for both solutions. Since both scenarios are focused on a service or product that puts individualization or personalization at the core of its value proposition, personalization might act more like a hygiene factor. Thus, the comparatively weaker effect of personalization might solely be due to the choice of example cases.

To be able to develop potential applications and extensions in this context, an intensive exchange with current and potential customers is just as essential as the expertise of experts. Regarding interactivity, an in-depth focus group evaluation of respective products and services will help with the provision of a solution that best fits the customer needs and is at the same time easy and interesting for the customers to use.

Even if not quite as pronounced, investment in service quality is also required. The survey shows that most respondents (99.3%) have not yet used any physical beauty tech devices and that the use of digital offerings is not universal, making it difficult to assess the importance of service quality and service infrastructure. In the future, a study addressing these aspects in more detail for physical products thus might provide added value, since the studies by Lele and Shaw [45] and Vongurai [59] underline the relevance of a high service quality.

As there is a high level of interest in both physical products and digital applications, it is important to investigate why the actual experience with them is still lagging. In terms of marketing, companies need to draw more attention to such solutions and provide potential customers with practical experiences so that they can become established.

Likewise, it is possible that respondents consider this type of physical device to be too expensive. In particular, devices that can assist with a physical impairment should be brought to market in such a way that they are affordable and do not imply a new type of inequality in terms of social inequality. A price sensitivity analysis should be carried out here, especially with the aim of identifying individual value-driving components of such solutions.

5.2. Theoretical Implications and Outlook

The results, in general, indicate that the adopted model structure is fitting to the research objective with all constructs, except for the risk factors, being well integrated. The study thus provides a contribution to the literature on beauty tech by linking product characteristics with customer experience, customer satisfaction, purchase intention, and dimensions of loyalty. The high coefficients of determination indicate that the model structure already contains the most relevant product characteristics.

The marginal integration of the risk factors into the model structure indicates that still some work has to be done in studying customer preconceptions of AI and AR technologies and in how far those pose as a detractor to the acceptance and adoption of beauty tech solutions that implement these technologies.

Purchase intention and loyalty, while explained quite well within the model, still report the smallest coefficients of determination. Thus, the results indicate that several impact factors are still unknown and thus omitted from the model. Those factors might include the aforementioned alternative risk factors, first and foremost the price.

A more detailed study of purchase intention and willingness-to-pay for beauty tech solutions would therefore be a suitable extension of the present study. Where this study only reports on effect strength and significance, a discrete choice study could determine the value of each of the characteristics and put a price tag on customer experience and satisfaction.

Where methodologically comparable studies like Lele and Shaw [45] consider AI and AR solutions in cosmetics as a monolithic entity or only consider a single solution, the estimation results and the preceding descriptive analysis indicate that both scenarios differ strongly from each other. As detailed in the introduction, the beauty tech industry consists of many more types of solutions than just the two considered in this article. While some research has been conducted on AR solutions, in particular on VTO, many types of beauty tech solutions are still not considered in the scientific literature at all. Since the results of this study suggest that differences exist, it remains an open question as to how far these results transfer to other types of beauty tech solutions and how the corpus of beauty tech solutions compares to each other.

5.3. Limitations

Each hypothesis formulation was based on constructs from the literature, but in retrospect it must be criticized that the individual questions in the questionnaire or their items do not adequately reflect the constructs throughout and only one-dimensional operationalizations were used. This limits the validity of the results. In the future, it should therefore be ensured that validated scales on the topic are developed and their quality consistently verified.

There are several dependency relationships that can influence each other at the same time, and it would have been more expedient to calculate a structural equation model. Furthermore, additional moderator or mediator effects were ignored in this study.

Currently, only limited literature on beauty tech exists that covers all components and technologies; sources that have not yet been subject to a peer review process had to be used to develop the theoretical basis [32,33].

Finally, the study is based on a sample that is representative only of the perceived customer base for beauty tech customers and less so for the German population. The number of participants is appropriate regarding the implemented methodology, but with 143 participants, it could be expanded in a broader study.

The fact that devices for barrier-free use were part of the study, but 142 people have not yet used them, also means that the task for the future is to address an adequate target group and work out whether these devices actually have added value for people with disabilities.

Even though it was explicitly stated that these are digital devices and services from the cosmetics sector, it is not clear how much experience the respondents have in this area. Chatbots ranked first among known applications, although they tend to be used less in the cosmetics industry in contrast to VTOs. It is conceivable that the respondents could have included their experience from other areas (e.g., when buying furniture) despite the reference to the industry, so that a different type of survey could be considered in the future.

Despite the limitations, this study provides a sound basis for delivering initial results on the topic, which may stimulate further research on the subject.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.K.P. and J.S.; validation, J.K.P.; formal analysis, J.K.P.; investigation, J.K.P.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.P. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.K.P. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- 0. Do you have an interest in cosmetics?

Understanding the terms AR and AI

This section briefly explains the terms augmented reality and artificial intelligence. If you are already familiar with these terms, you can skip this section and start answering the questions right away.

Augmented reality (AR)

AR describes the technology used to integrate virtual elements into the real environment. This can be done, for example, with AR glasses, the camera of a smartphone/tablet, or a laptop.

Example: The use of virtual try-ons (VTOs) in online shops—here, products such as lipsticks, eye shadow, etc. can be virtually tested or tried on before purchase by transferring these elements to the face in real time. Users can thus see how a particular look or color would look on their face.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI describes the technology used to develop computer programs or machines that act intelligently like humans and solve problems independently.

Example: The use of digital services (voice assistants or diagnostic tools) that provide personalized recommendations based on a vast amount of collected data, tailored to the individual skin or hair characteristics of consumers.

- Digital services in the cosmetics industry

- In the following, you will be asked about your knowledge and use of digital services in the cosmetics industry.

- 1.

- Please indicate how familiar you are with the following digital services and mark accordingly if you are not familiar with a service.(5-point Likert scale)

- Virtual try-ons (virtual testing of cosmetic products, e.g., lipstick)

- AR filters for the entire face (e.g., makeup filters via Microsoft Teams)

- Virtual 1:1 live consultation (e.g., by booking a virtual appointment)

- AI-based advisor (e.g., analyzing facial features to display recommended looks and provide tips on how to recreate the look)

- AI-based product/gift finder (e.g., for perfumes, based on favorite scents and a short questionnaire)

- Color finder (e.g., to find the perfect color of makeup foundation)

- Voice-activated assistants that provide personalized recommendations

- AI-based chatbots

- Other (optional):

- 2.

- Were you unaware of any of the digital services mentioned above?Note: Please only answer “Yes” if you previously answered “I am not familiar with this digital service” for ALL digital services.

- 3.

- Which of the above digital services in the cosmetics industry have you already used?*Multiple answers possible

- Virtual try-ons (virtual testing of cosmetic products, e.g., lipstick)

- AR filters for the entire face (e.g., makeup filters via Microsoft Teams)

- Virtual 1:1 live consultation (e.g., by booking a virtual appointment)

- AI-based advisor (e.g., analyzing facial features to display recommended looks and receive tips on how to recreate the look)

- AI-based product/gift finder (e.g., for perfumes, based on favorite scents and a short questionnaire)

- Color finder (e.g., to find the perfect color of makeup foundation)

- Voice-activated assistants that provide individual recommendations

- AI-based chatbots

- Other (optional):

- Wearables

- Wearables are devices that are worn directly on the body. The screenshot shows an example of La Roche Posay’s “My Skin Track UV”—a UV sensor that alerts you to your personal exposure to UV radiation, air pollution, pollen, and humidity and provides personalized tips on what to do (via app).

- 4.

- Please rate this type of device in terms of interest, usefulness, and use.These are exclusively wearables from the cosmetics industry.(4-point Likert scale)

- I find the device interesting.

- If the device were relevant to me, I could imagine using it.

- I have already used such a device.

- Devices for producing customized products/formulations at the touch of a button

- These are devices that enable the production of customized formulations or products at home. The screenshot shows an example of the “Cosmechip” device from Amorepacific, which can produce skin care products based on your individual skin needs at the touch of a button.

- 5.

- Please rate this type of device in terms of interest, usefulness, and use.(4-point Likert scale)

- I find the device interesting.

- If the device were relevant to me, I could imagine using it.

- I have already used such a device.

- Devices for faster application of cosmetics

- These are devices that enable faster application of cosmetic products for home use. The screenshot shows an example of the “Colorsonic” device from L’Oréal Paris—a hair coloring device that mixes the color itself and applies it evenly and quickly with 300 movements per minute without leaving any mess.

- 6.

- Please rate this type of device in terms of interest, usefulness, and use.(4-point Likert scale)

- I find the device interesting.

- If the device were relevant to me, I could imagine using it.

- I have already used such a device.

- Devices for barrier-free application of cosmetics in everyday life

- These are devices that make it easier for people with certain limitations to apply cosmetics in everyday use. The screenshot shows an example of the “HAPTA” device from Lancôme, which enables people with limited hand and arm mobility to apply lipstick evenly using intelligent motion sensors.

- 7.

- Please rate this type of device in terms of interest, usefulness, and use.(4-point Likert scale)

- I find the device interesting.

- If the device were relevant to me, I could imagine using it.

- I have already used such a device.

- Presentation of scenarios

- Now you will be presented with two scenarios, first one about a digital service, then one about a physical device.

- Scenario 1: L’Oréal Paris Beauty Genius

Imagine you were using the following digital tool:

A digital tool that combines several of the digital services already mentioned. L’Oréal recently unveiled “Beauty Genius” at one of the world’s largest technology trade shows (CES). This virtual voice assistant can diagnose skin conditions using a selfie to identify individual skin needs and problems. Based on this, the voice assistant suggests individual product recommendations and explains how to use them to achieve the desired skin appearance. In addition, the assistant offers video tutorials in the chat history so that customers can learn more and educate themselves. The same applies to decorative cosmetics—here, the voice assistant can provide product recommendations that customers can test directly using Virtual Try-On and purchase if desired.

- 8.

- How likely is it that using such a tool would trigger the following emotions and feelings in you?(4-point Likert scale)

- Curiosity

- Fun

- Joy

- Overwhelm

- Boredom

- Aversion

- 9.

- Please indicate to what extent the following statements apply to you.(4-point Likert scale)

- I can imagine that the tool would perform satisfactorily.

- I would rely on the recommendations of this tool.

- The tool would allow me a wide range of interaction options.

- I could interact with virtual product presentations to obtain product-related information that meets my specific needs.

- The tool would provide me with positive added value.

- The tool would allow me to personalize my consumption.

- I recognize potential problems and risks in using this tool.

- I can imagine that the tool’s functions would work without any problems.

- I can imagine that the quality of the service (e.g., AR function, personalized recommendations) is good.

- The recommendation would provide me with important information for my decisions.

- The recommendation would be informative.

- The recommendation would be helpful.

- 10.

- How likely are you to purchase the recommended product based on personalized recommendations from the integrated digital services “Virtual Try-On”?(e.g., recommended skin care serum or recommended lipstick)

- 11.

- Why would you purchase the recommended product?*Multiple answers possible

- I imagine that it meets my individual (skin/makeup) needs.

- I imagine that I will receive sufficient information about the product recommended by the tool.

- I imagine that I will receive sufficient information in response to my questions.

- I imagine that I will receive sufficient information about how to use the product (e.g., tips).

- I imagine that the product looks realistic during virtual testing.

- I imagine that I can test/switch between different functions myself (e.g., change colors, turn my face).

- I imagine that there are other reasons for buying it:

- 12.

- What would prevent you from buying the recommended product?*Multiple answers possible

- The quality of the appearance during virtual testing is not realistic enough.

- I do not trust the technology.

- I prefer to buy the product in a brick-and-mortar store.

- The information is not sufficient to make a decision.

- Other (optional):

- 13.

- How likely is it that...(4-point Likert scale)

- you would recommend the tool to your friends or family after satisfactory use?

- you would use the tool again after satisfactory use?

- using this tool would lead to fewer bad purchases due to personalized recommendations and virtual testing?

- using this tool would lead to you buying more products from the brand that was recommended to you?

- using this tool will result in you buying fewer products from the brand that was recommended to you?

- Scenario 2: YSL Rouge Sur Mesure

Imagine you owned the following product:

A device that allows you to create your desired lipstick color at home at the touch of a button: 1 device, 4000 lipstick shades. Using an app, you can select the desired color with the help of your smartphone camera and a color picker. This is then mixed in the handy device with the help of three color cartridges, and you get the desired color within seconds. In addition, the intelligent technology can generate color recommendations based on color harmony rules to find a matching shade. Another feature: the lid can be removed so that the new lipstick creation can be taken with you on the go.

- 14.

- How likely is it that using such a device would trigger the following emotions and feelings in you?(4-point Likert scale)

- Curiosity

- Fun

- Joy

- Overwhelm

- Boredom

- Aversion

- 15.

- Please indicate to what extent the following statements apply to you.(4-point Likert scale)

- I can imagine that the device would perform satisfactorily.

- I trust that the device would perform as desired (e.g., that the lipstick color would actually look the way you imagined it).

- The device would allow me a wide range of interaction options.

- I could interact with virtual product representations in the app to obtain product-related information that meets my specific needs.

- The device would provide me with positive added value.

- The device would allow me to personalize my consumption.

- I recognize potential problems and risks in using this device.

- I can imagine that the device’s functions would work without any problems.

- I can imagine that the quality of the service (e.g., AR function, personalized recommendations) would be good.

- The recommendation would provide me with important information for my decisions.

- The recommendation would be informative.

- The recommendation would be helpful.

- 16.

- How likely are you to purchase this device?

- 17.

- What would motivate you to purchase this device?* Multiple answers possible

- It allows me to produce the exact shade I need in seconds.

- It allows me to produce the quantity I need.

- It gives me the flexibility to produce at any time/any place.

- It saves me money in the long run.

- It saves me a trip to the store.

- Other.

- 18.

- How likely is it that…(4-point Likert scale)

- You would recommend the device to your friends or family after satisfactory use?

- Using this device would lead you to buy more products from the brand?

- Using this device would lead you to buy fewer products from the brand?

- Using this tool leads to fewer bad purchases (e.g., due to the customized lipstick color)?

- Using this device reduces your purchase of conventional lipsticks (e.g., because you can now make any color you want yourself)?

- 19.

- In your opinion, what are currently the biggest concerns regarding the use of the aforementioned AR and AI-based services and devices?

- Data protection and data security

- Reliability of results

- Quality of appearance

- Excessive invasion of privacy

- Other:

- 20.

- Please indicate your gender.Male, Female, Diverse

- 21.

- Which age category do you belong to?Categorized

- 22.

- Please indicate your current employment status.

- 23.

- Please indicate your monthly net income.Categorized

References

- DOUGLAS. Douglas Startet Neues KI-Tool zur Hautanalyse. Available online: https://douglas.group/de/newsroom/pressemitteilungen/douglas-startet-neues-ki-tool-zur-hautanalyse (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- McKinsey & Company. The State of Fashion: Beauty. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-beauty-market-in-2023-a-special-state-of-fashion-report (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Stoll, S. 2023 Beauty-Trends: Seamless Consumer: Auf der Suche nach Persönlicher Selbstfindung. INSIDE Beauty 2023, 1. Available online: https://www.rheingold-marktforschung.de/rheingold-in-den-medien/beauty-trends-2023/ (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Roettig, B. Kosmetik: Mit Virtueller Beratung BESSER Verkaufen. Available online: https://regalplatz.com/kosmetik-mit-virtueller-beratung-besser-verkaufen/ (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ustymenko, R. Trends and innovations in cosmetics marketing: Introduction. Econ. Educ. 2023, 8, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CitrusBits Inc. How Augmented Reality Is Being Used in E-Commerce: Trends in E-Commerce. Available online: https://www.citrusbits.com/how-augmented-reality-is-being-used-in-ecommerce (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Gränzdörffer, A.; Jantz, S. Make-Up-Innovationen: Neue Technologien, die für eine Veränderung in der Kosmetikindustrie Sorgen: Welche Anwendungen und Beauty-Techniken sind auf dem Vormarsch. Available online: https://www.beauty.de/de/Media_News/BEAUTY_News/Produkte/Produkte/Make-up-Innovationen_Neue_Technologien,_die_f%C3%BCr_eine_Ver%C3%A4nderung_in_der_Kosmetikindustrie_sorgen (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Abdallah, M.S.; Cho, Y.-I. Virtual Hairstyle Service Using GANs & Segmentation Mask (Hairstyle Transfer System). Electronics 2022, 11, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Oréal Groupe. YSL Rouge Sur Mesure: A Beauty Tech Innovation Powered by Perso. Personalized Lipstick Paves the Way to a New Beauty Tech Era. Available online: https://www.loreal.com/en/articles/science-and-technology/ysl-perso/ (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- L’Oréal Finance. L’Oréal Groupe Beauty Tech Innovation, HAPTA, Earns ‘TIME Best Inventions 2023’ Accolade. Available online: https://www.loreal-finance.com/eng/news-event/loreal-groupe-beauty-tech-innovation-hapta-earns-time-best-inventions-2023-accolade (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Wynne, A. L’Oréal’s Barbara Lavernos on Staying on Top in Beauty Tech. Available online: https://wwd.com/business-news/technology/loreal-barbara-lavernos-top-beauty-tech-generative-ai-1235682171/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Debter, L. You Can Try Makeup Online Before You Buy It, Thanks to This Woman Entrepreneur. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurendebter/2023/01/10/perfect-corp-alice-chang-virtual-try-on-technology-beauty/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Caliò, S.; Sabanoglu, T. Beauty Tech: A Statista Dossierplus on the AI- and AR- Powered Use of Technology Applications in the Global Beauty Market. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/116101/beauty-tech/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Gilbert, J. How L’Oréal adopted new technologies to scale personalisation, adapt to new customer demands and evolve into the top beauty tech company. J. Digit. Soc. Media Mark. 2021, 2, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Oréal Groupe. Beauty Tech: Für L’Oréal Bedeutet Schönheit Innovation. Available online: https://www.loreal.com/de-de/germany/articles/science-and-technology/beauty-tech-de/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Perfect Corp. Tarte Sees “Triple Digit Increase” in Time Spend on Site, 30% Jump in Add-To-Cart Using Virtual Try-On. Available online: https://www.perfectcorp.com/business/successstory/tarte (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Golden Arrow. How AI Can Help Create a More Sustainable Beauty Industry. Available online: https://www.goldenarrow.com/blog/how-ai-can-help-create-more-sustainable-beauty-industry (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Olavsrud, T. Estée Lauder Transformiert: Mit KI zur Barrierefreien Kosmetik. Available online: https://www.cio.de/a/mit-ki-zur-barrierefreien-kosmetik,3615186 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- De Araújo, A.; Vega, K.; Castro, T.; Gadelha, B. Beauty tech nails: Towards interaction and functionality. In Proceedings of the IHC 2020—Proceedings of the 19th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Diamantina, Brazil, 26–30 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjermedal, G. Beauty Tech & Neueste Trends: Der komplette Leitfaden 2024. Available online: https://www.perfectcorp.com/de/business/blog/general/der-komplette-beauty-tech-leitfaden#1701266802901-1 (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Astle, K. E-Commerce vs. Retail: Is Beauty Tech Changing the Way We Buy Cosmetics?: Challenges and Opportunities. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/e-commerce-vs-retail-beauty-tech-changing-way-we-buy-cosmetics-astle-sozpe (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Riar, M.; Xi, N.; Korbel, J.J.; Zarnekow, R.; Hamari, J. Using augmented reality for shopping: A framework for AR induced consumer behavior, literature review and future agenda. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 242–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.; Ajriya, A.D.; Fahmi, C.; Handayani, P.W. The influence of augmented reality on e-commerce: A case study on fashion and beauty products. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2208716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Q. Privacy concerns, perceived intrusiveness, and privacy controls: An analysis of virtual try-on apss. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, A.R.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; van Noort, G.; Neijens, P.C. Shopping in augmented reality: The effects of spatial presence, personalization and intrusiveness on app and brand responses. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.J.; Kwon, K.H. An application of AR in cosmetological industry after coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. J. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5314–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, M.-C.; Sirghi, N.; Toth, D.-M. Consumers’ experience and satisfaction using augmented reality apps in e-shopping: New empirical evidence. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, C.G.; Maupa, H.; Payangan, O.R. The future of online beauty retail: The effectiveness of augmented reality technology in influencing psychological reaction and behavioral intention. Int. Res. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 2, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Smink, A.R.; Frowijn, S.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; van Noort, G.; Neijens, P.C. Try online before you buy: How does shopping with augmented reality affect brand responses and personal data disclosure. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simay, A.E.; Wei, Y.; Gyulavári, T.; Syahrivar, J.; Gaczek, P.; Hofmeister-Tóth, Á. The e-WOM intention of artificial intelligence (AI) color cosmetics among Chinese social media influencers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 36, 1569–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim Zadegan, M.; Farahkakhsh, S.; Bellini, F. The influence of augmented reality on purchase and repurchase intention in the fashion industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics and Social Sciences; Dima, A.M., Vargas, V.M., Eds.; Sciendo: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; pp. 714–721. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, E.; Dudkina, L. The Influence of Interactive Product Visualization on Customer Satisfaction: An Investigation Based on SOR Model; Jönköping University School of Engineering: Jonkoping, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1673196/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Kanaska, S.D. Is the Future of Beauty Personalized?: Case Study for Microbiome Skincare Brand Skinome. Available online: https://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1703718/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Netscher, M.; Rehrl, T.; Jordan, S.; Roschmann, M.; Seibel, D.; Kill, K.; Heppler, P.; Lunkenheimer, M.; Kracklauer, A. AI in cosmetics: Determinants influencing the acceptance of product configurators. Bavar. J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 6, 535–548. [Google Scholar]

- Hilken, T.; de Ruyter, K.; Chylinski, M.; Mahr, D.; Keeling, D.I. Augmenting the eye of the beholder: Exploring the strategic potential of augmented reality to enhance online service experiences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminesh, A.; Pinsoneeault, A.; Yang, S.B.; Oh, W. An odyssey into virtual worlds: Exploring the impacts of technological and spatial environments on intention to purchase virtual products. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 789–810. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, S.; Mai, R.; Pagel, T. Toy or Tool? Utilitarischer und hedonischer Nutzen mobiler Augmented Reality-Apps. HMD Prax. Der Wirtsch. 2022, 59, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ifekanandu, C.C.; Anene, J.; Ewuzie, C.; Iloka, C. Influence of artificial intelligence (AI) on customer experience and loyalty: Mediating role of personalization. J. Data Acquis. Process. 2023, 38, 1936–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X. AI technology and online purchase intention: Structural equation model based on perceived value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Kasilingam, D.; Arora, P.; Soni, S. The effect of augmented reality in mobile applications on consumers’ online impulse purchase intention: The mediating role of perceived value. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, F.P.; Gui, A. Enhancing Consumer Control: Virtual Try-On Experiences in the Indonesian Beauty and Cosmetics Industry. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications, ICoDSA 2024, Bali, Indonesia, 10–11 July 2024; pp. 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletto, V.; Accardi, S.; Fici, A.; Piccoli, F.; Rossi, C.; Bilucaglia, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M. Enjoy it! Cosmetic try-on apps and augmented reality, the impact of enjoyment, informativeness and ease of use. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1515937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberger, M.; Tartarin, A.; Lee, S.K. Exploring consumer satisfaction with an AR beauty app based on the technology acceptance model and experience economy theory. J. Mark. Anal. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]