Palatal Vault Depth Affects the Accuracy of the Intaglio Surface of Complete Maxillary Denture Bases Manufactured Through Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

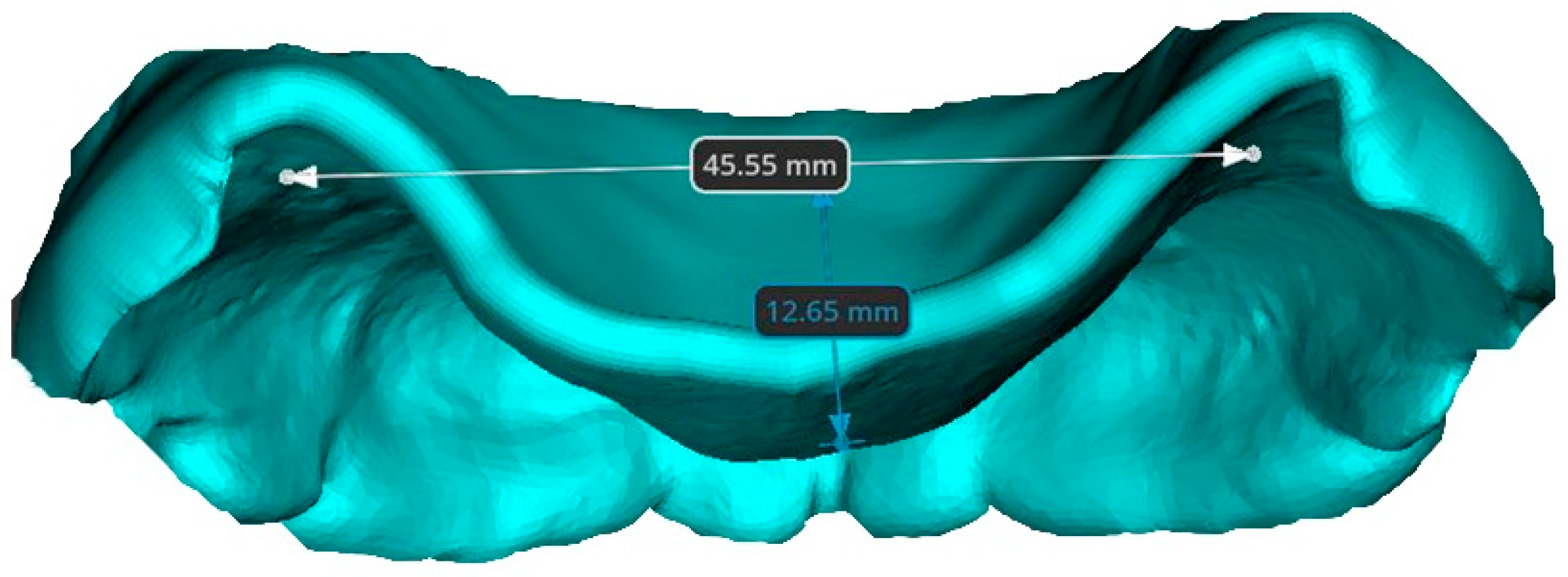

2. Methodology

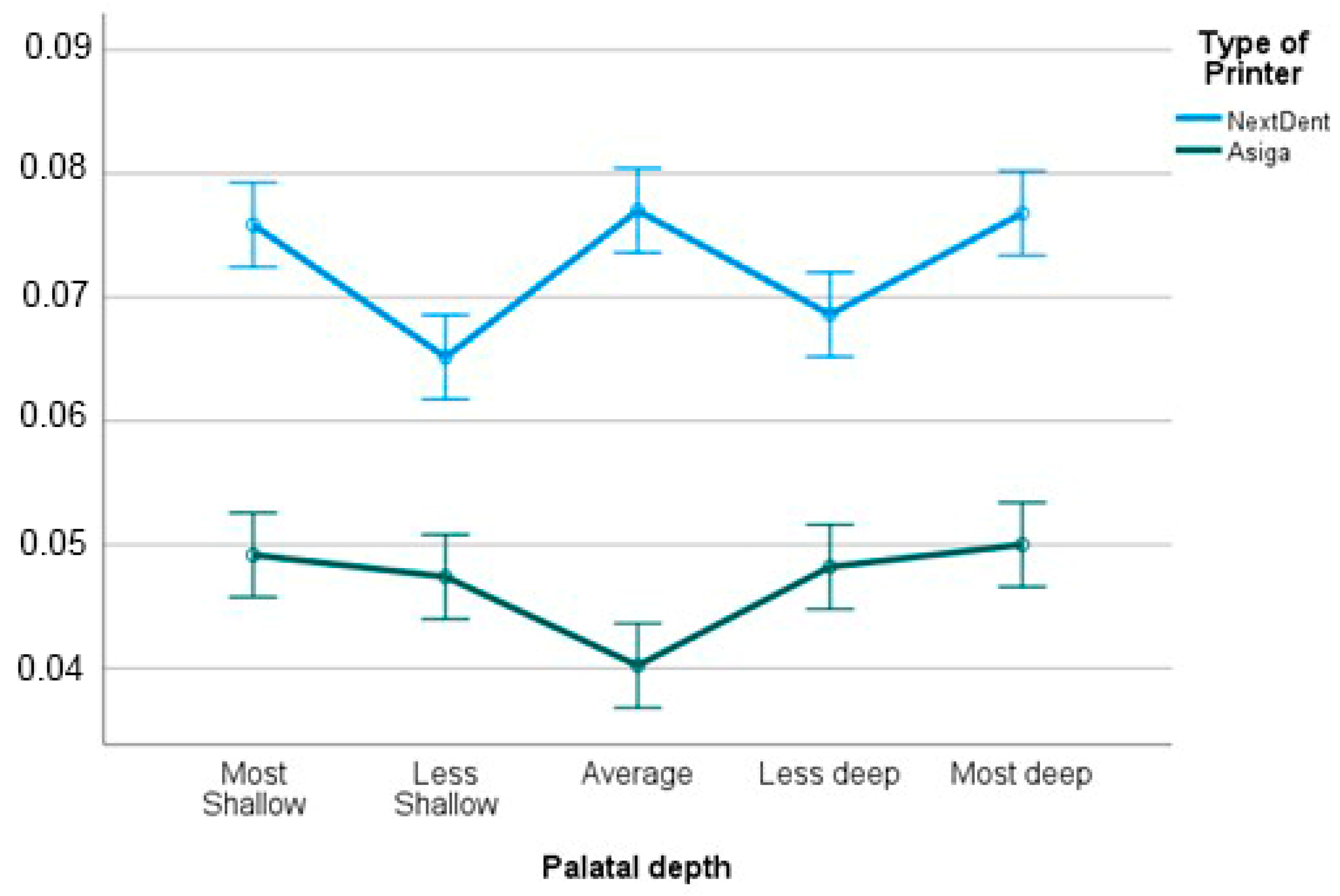

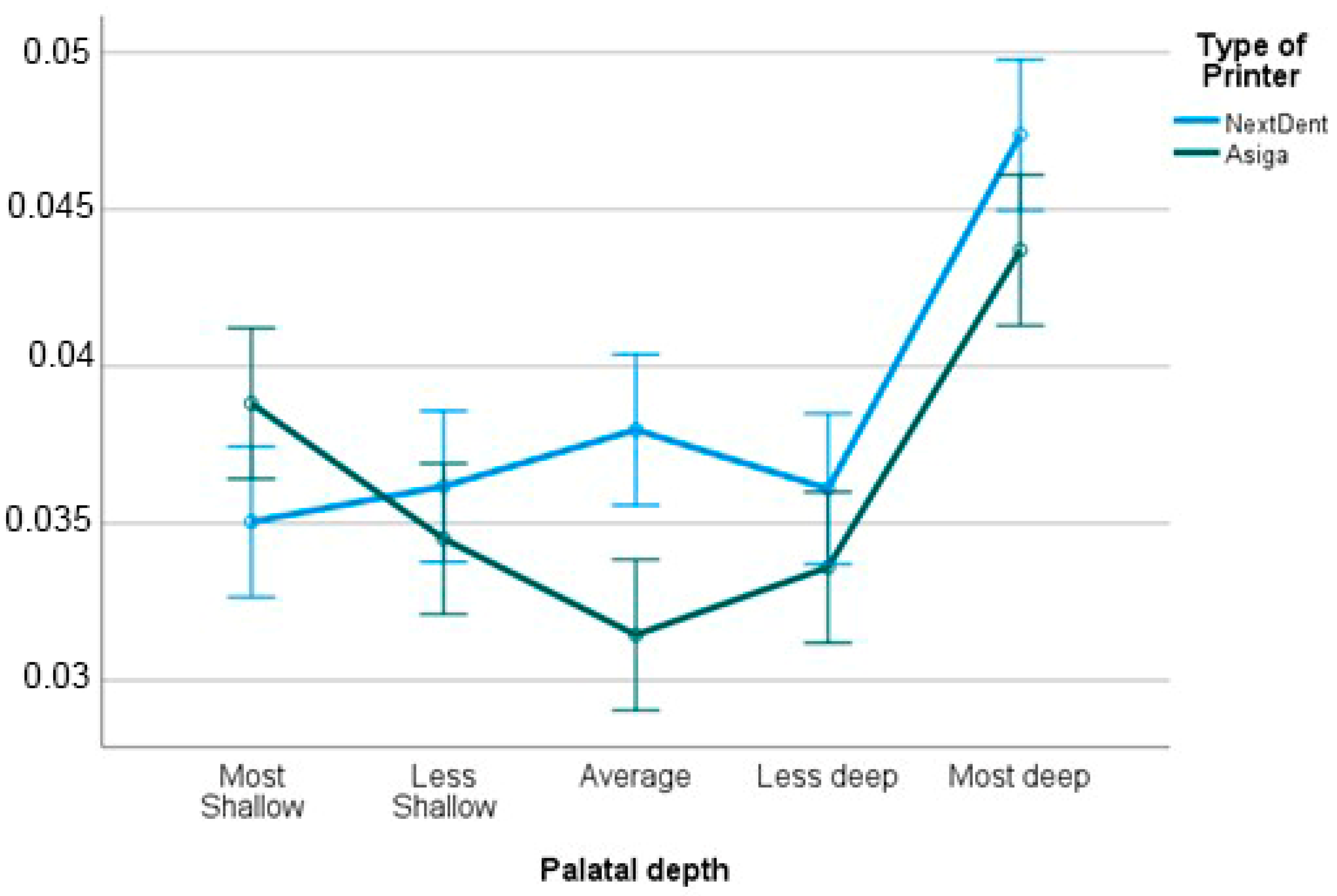

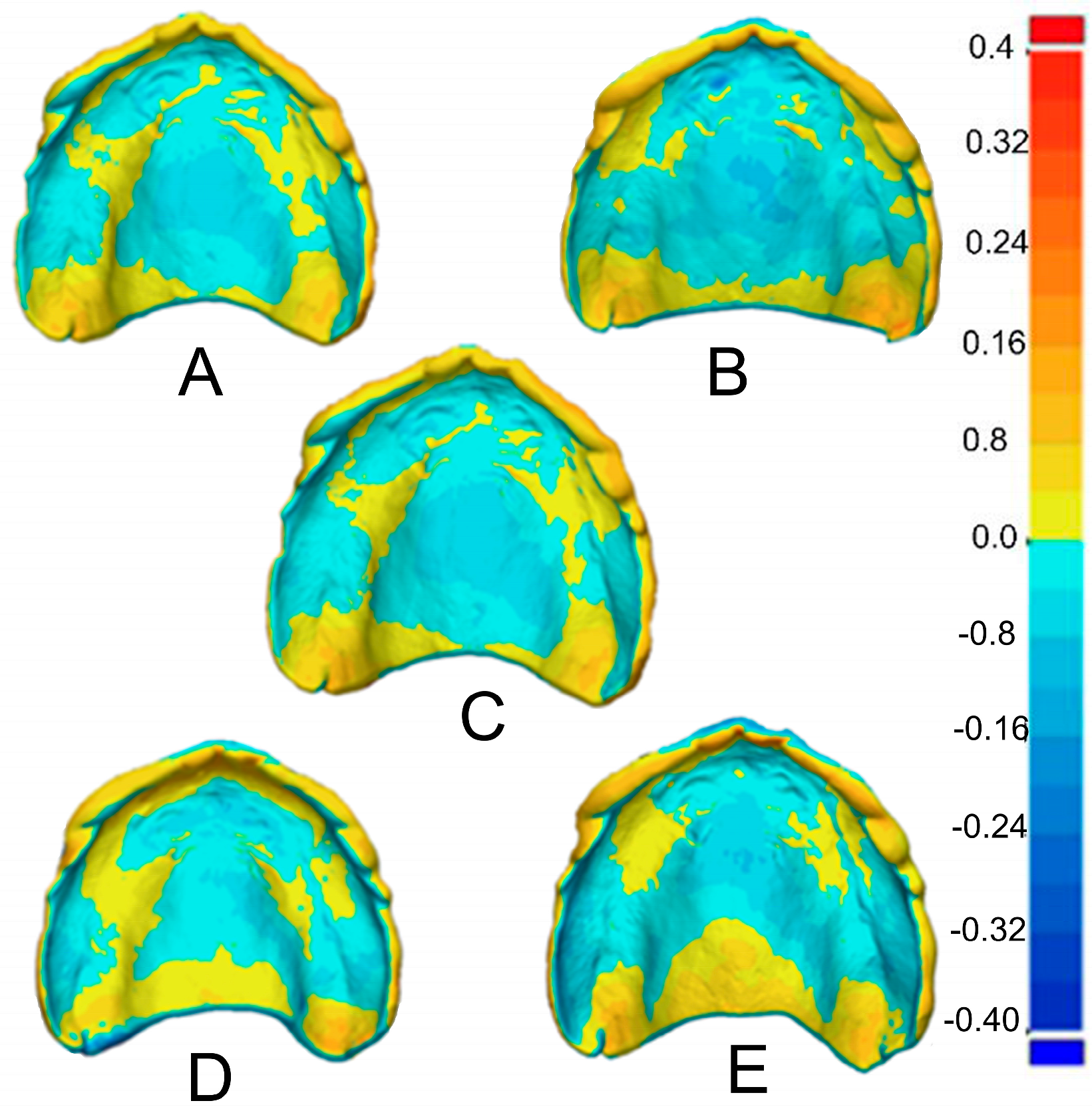

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

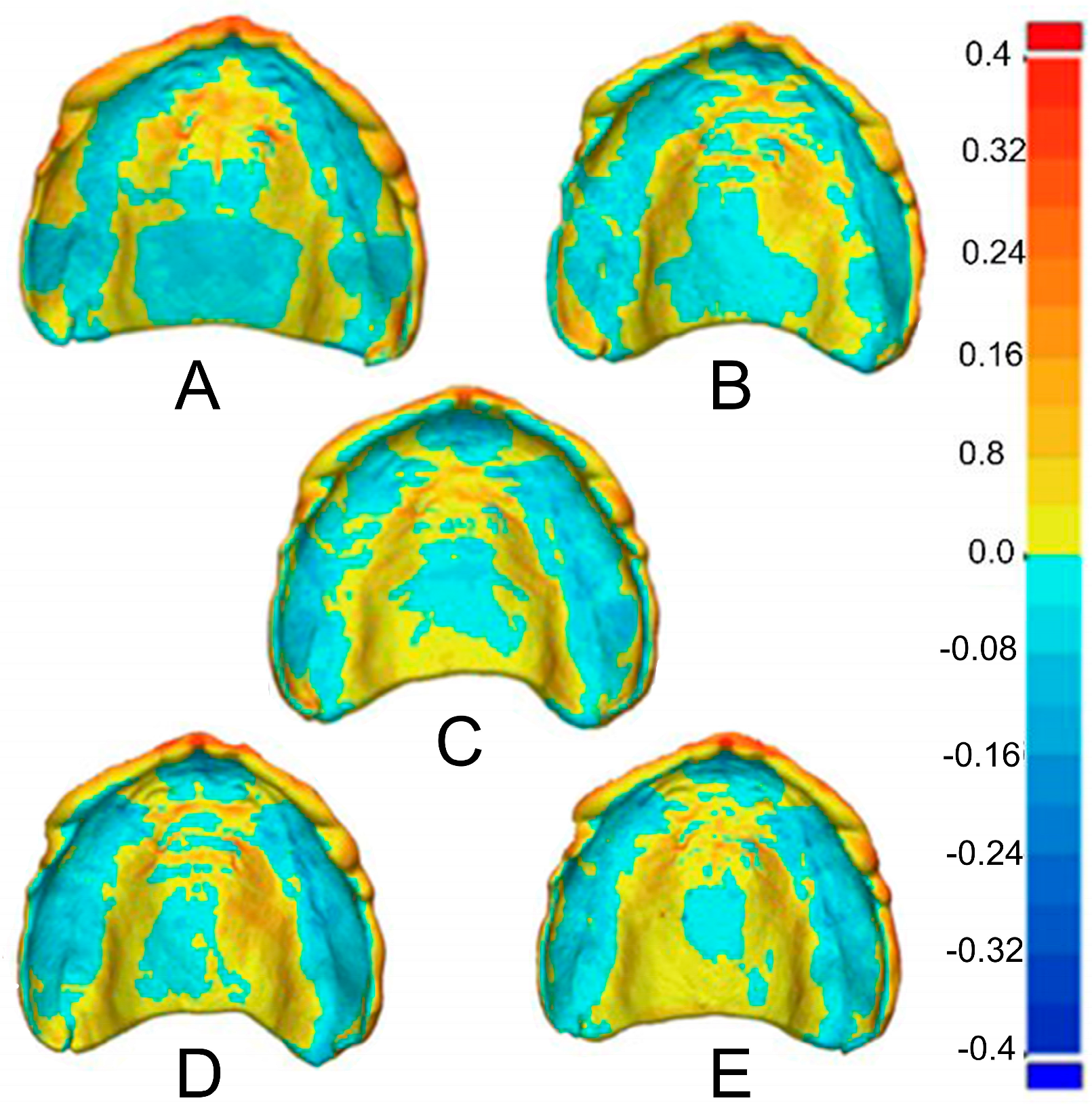

- Very deep palatal vaults (17.8 mm) are linked to higher levels of negative deviation and less trueness of DLP 3D-printed complete maxillary denture bases manufactured through additive manufacturing. No clear pattern emerged for less deep, average, or shallow palatal vault depths.

- Different 3D printers, even within the same technology type, demonstrate a combined difference with varying anatomical shapes, confirming that variations between 3D printing systems observed in other in vitro studies are not because of the specific sample utilized for analysis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zarb, G.A. Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients: Complete Dentures and Implant-Supported Prostheses, 13th ed.; Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smets, K.; Vandeweghe, S.; Ongenae, L.; D’Haese, R. Complications of 3D printed dentures: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025; in Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvell, B.W.; Clark, R.K. The physical mechanisms of complete denture retention. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 189, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmassl, O.; Dumfahrt, H.; Grunert, I.; Steinmassl, P.A. Influence of CAD/CAM fabrication on denture surface properties. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2018, 45, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Shi, Y.F.; Xie, P.J.; Wu, J.H. Accuracy of digital complete dentures: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cameron, A.B.; Heng, N.C.K.; Aarts, J.M.; Choi, J.J.E. Occlusal accuracy of digitally manufactured removable dentures: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J. Dent. 2025, 162, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.B.; Evans, J.L.; Abuzar, M.A.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Love, R.M. Trueness assessment of additively manufactured maxillary complete denture bases produced at different orientations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.B.; Kim, H.; Evans, J.L.; Abuzar, M.A.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Alifui-Segbaya, F. Maxillary intaglio surface of CNC milled versus 3D printed complete denture bases—An in vitro investigation of the accuracy of seven systems. J. Dent. 2024, 151, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namano, S.; Kanazawa, M.; Katheng, A.; Trang, B.N.H.; Hada, T.; Komagamine, Y.; Iwaki, M.; Minakuchi, S. Effect of support structures on the trueness and precision of 3D printing dentures: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5725-1:2023; Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Measurement Methods and Results—Part 1: General Principles and Definitions. International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J.; Baba, N.Z.; Kattadiyil, M.T. Comparison of denture base adaptation between CAD-CAM and conventional fabrication techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hong, S.J.; Paek, J.; Pae, A.; Kwon, K.R.; Noh, K. Comparing accuracy of denture bases fabricated by injection molding, CAD/CAM milling, and rapid prototyping method. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2019, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.E.-L.; Helal, M.A. Evaluation of the effect of thermocycling on the trueness and precision of digitally fabricated complete denture bases. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhamdi, M.A.; Gad, M.M. Impact of Printing Orientation on the Accuracy of Additively Fabricated Denture Base Materials: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Russo, L.; Guida, L.; Zhurakivska, K.; Troiano, G.; Chochlidakis, K.; Ercoli, C. Intaglio surface trueness of milled and 3D-printed digital maxillary and mandibular dentures: A clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalberer, N.; Mehl, A.; Schimmel, M.; Muller, F.; Srinivasan, M. CAD-CAM milled versus rapidly prototyped (3D-printed) complete dentures: An in vitro evaluation of trueness. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, M.S.; Baytaroğlu, E.N.; Erdem, A.; Dilber, E. A review of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacture techniques for removable denture fabrication. Eur. J. Dent. 2016, 10, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Upadhyay, A.; Khayambashi, P.; Farooq, I.; Sabri, H.; Tarar, M.; Lee, K.T.; Harb, I.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dental 3D-Printing: Transferring Art from the Laboratories to the Clinics. Polymers 2021, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caussin, E.; Moussally, C.; Le Goff, S.; Fasham, T.; Troizier-Cheyne, M.; Tapie, L.; Dursun, E.; Attal, J.P.; François, P. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing in dentistry: A comprehensive review of actual popular technologies. Materials 2024, 17, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paral, S.K.; Lin, D.Z.; Cheng, Y.L.; Lin, S.C.; Jeng, J.Y. A review of critical issues in high-speed vat photopolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.B.; Abuzar, M.A.; Figueredo, C.M.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Evans, J.L. Do bar supports affect the accuracy of mandibular complete denture bases produced with additive manufacturing at different printing orientations: An in vitro evaluation. Digit. Dent. J. 2025, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarpour, D.; El-Amier, N.; Tahboub, K.; Zimmermann, E.; Pero, A.C.; de Souza, R. Effects of DLP printing orientation and postprocessing regimes on the properties of 3D printed denture bases. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 134, 239.e1–239.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Aljohani, R.; Almuzaini, S.; Alghauli, M.A. Physical–mechanical properties and accuracy of additively manufactured resin denture bases: Impact of printing orientation. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2025, 69, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharechahi, J.; Asadzadeh, N.; Shahabian, F.; Gharechahi, M. Dimensional changes of acrylic resin denture bases: Conventional versus injection-molding technique. J. Dent. 2014, 11, 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Chintalacheruvu, V.K.; Balraj, R.U.; Putchala, L.S.; Pachalla, S. Evaluation of Three Different Processing Techniques in the Fabrication of Complete Dentures. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2017, 7, S18–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzar, M.A.M.; Jamani, K.; Abuzar, M. Tooth Movement during Processing of Complete Dentures and Its Relation to Palatal Form. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1995, 73, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Manjunath, S.; Vajawat, M. Effect of palatal form on movement of teeth during processing of complete denture prosthesis: An in-vitro study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.B.; Ramos, V., Jr.; Dickinson, D.P. Comparison of Fit of Dentures Fabricated by Traditional Techniques Versus CAD/CAM Technology. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, M.; Iplikcioglu, H. An analysis of edentulous maxillary arch width and palatal height. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1992, 5, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cawood, J.I.; Howell, R.A. A classification of the edentulous jaws. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 17, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.I.; Hwang, H.J.; Ohkubo, C.; Han, J.S.; Park, E.J. Evaluation of the trueness and tissue surface adaptation of CAD-CAM mandibular denture bases manufactured using digital light processing. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiamornsup, P.; Katheng, A.; Ha, R.; Tsuchida, Y.; Kanazawa, M.; Uo, M.; Minakuchi, S.; Suzuki, T.; Takahashi, H. Effects of build orientation and bar addition on accuracy of complete denture base fabricated with digital light projection: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 67, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grymak, A.; Badarneh, A.; Ma, S.; Choi, J.J.E. Effect of various printing parameters on the accuracy (trueness and precision) of 3D-printed partial denture framework. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 140, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casucci, A.; Verniani, G.; Bonadeo, G.; Fadil, S.; Ferrari, M. Analog and digital complete denture bases accuracy and dimensional stability: An in-vitro evaluation at 24 hours and 6 months. J. Dent. 2025, 157, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, F.Y.; Wu, G.H.; Zhang, W.; Yin, J. Measurement of mucosal thickness in denture-bearing area of edentulous mandible. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, A.; Feng, C.; Chochlidakis, K.; Russo, L.L.; Ercoli, C. A comparison of alveolar ridge mucosa thickness in completely edentulous patients. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.B.; Abuzar, M.A.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Evans, J.L. Assessment of clinical reproducibility for intraoral scanning on different anatomical regions for the complete maxillary edentulous arch with two intraoral scanners. J. Dent. 2024, 153, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghauli, M.A.; Almuzaini, S.A.; Aljohani, R.; Alqutaibi, A.Y. Impact of 3D printing orientation on accuracy, properties, cost, and time efficiency of additively manufactured dental models: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Palatal Vault Depth | NextDent Mean (SD) † | Post Hoc Results ‡ | Asiga Mean (SD) * | Post Hoc Results ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Shallow (A) | 0.076 (0.006) | A > B | 0.049 (0.003) | A > C |

| Less Shallow (B) | 0.065 (0.010) | B < C, E | 0.047 (0.002) | B > C |

| Average (C) | 0.077 (0.006) | C > B | 0.040 (0.002) | C < D, E C > A, B |

| Less Deep (D) | 0.069 (0.004) | 0.048 (0.002) | D > C | |

| Most Deep (E) | 0.077 (0.009) | E > B | 0.050 (0.002) | E > C |

| Overall | 0.073 (0.008) | 0.047 (0.004) |

| Palatal Vault Depth | NextDent Mean (SD) † | Post Hoc Results ‡ | Asiga Mean (SD) * | Post Hoc Results ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Shallow (A) | 0.035 (0.004) | A < E | 0.039 (0.003) | A > C |

| Less Shallow (B) | 0.036 (0.004) | B < E | 0.035 (0.003) | B < E |

| Average (C) | 0.038 (0.003) | C < E | 0.031 (0.002) | C < E |

| Less deep (D) | 0.036 (0.003) | D < E | 0.034 (0.002) | D < E |

| Most deep (E) | 0.047 (0.004) | E > A, B, C, D | 0.044 (0.007) | E > C, D |

| Overall | 0.039 (0.006) | 0.036 (0.006) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Smith, B.J.; George, L.; Davari, D.; Collins, J.; Orth, J.; Bakr, M.M.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Cameron, A.B. Palatal Vault Depth Affects the Accuracy of the Intaglio Surface of Complete Maxillary Denture Bases Manufactured Through Additive Manufacturing. Oral 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010007

Smith BJ, George L, Davari D, Collins J, Orth J, Bakr MM, Tadakamadla SK, Cameron AB. Palatal Vault Depth Affects the Accuracy of the Intaglio Surface of Complete Maxillary Denture Bases Manufactured Through Additive Manufacturing. Oral. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Ben J., Louis George, Duman Davari, Jeremy Collins, Jordan Orth, Mahmoud M. Bakr, Santosh Kumar Tadakamadla, and Andrew B. Cameron. 2026. "Palatal Vault Depth Affects the Accuracy of the Intaglio Surface of Complete Maxillary Denture Bases Manufactured Through Additive Manufacturing" Oral 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010007

APA StyleSmith, B. J., George, L., Davari, D., Collins, J., Orth, J., Bakr, M. M., Tadakamadla, S. K., & Cameron, A. B. (2026). Palatal Vault Depth Affects the Accuracy of the Intaglio Surface of Complete Maxillary Denture Bases Manufactured Through Additive Manufacturing. Oral, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010007