Experiences with Cling Film and Dental Dam Use in Oral Sex: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Oral Sex

1.2. Global Epidemiology of Oral Sex

1.3. Health Benefits of Oral Sex

1.4. Health Risks of Oral Sex

1.5. Physical Barrier Use: A Safer Oral Sex Practice

1.6. Problem Statement

1.7. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Reporting Guideline

2.3. Title and Protocol Registration

2.4. Search Strategy for Identifying Studies

2.4.1. Electronic Databases

2.4.2. Other Sources

2.5. Deduplication of Identified Studies

2.6. Screening and Selection of Studies

2.7. Quality Appraisal of Selected Literature

2.8. Data Extraction

2.9. Data Synthesis

2.10. Configuration of Synthesised Data

3. Results

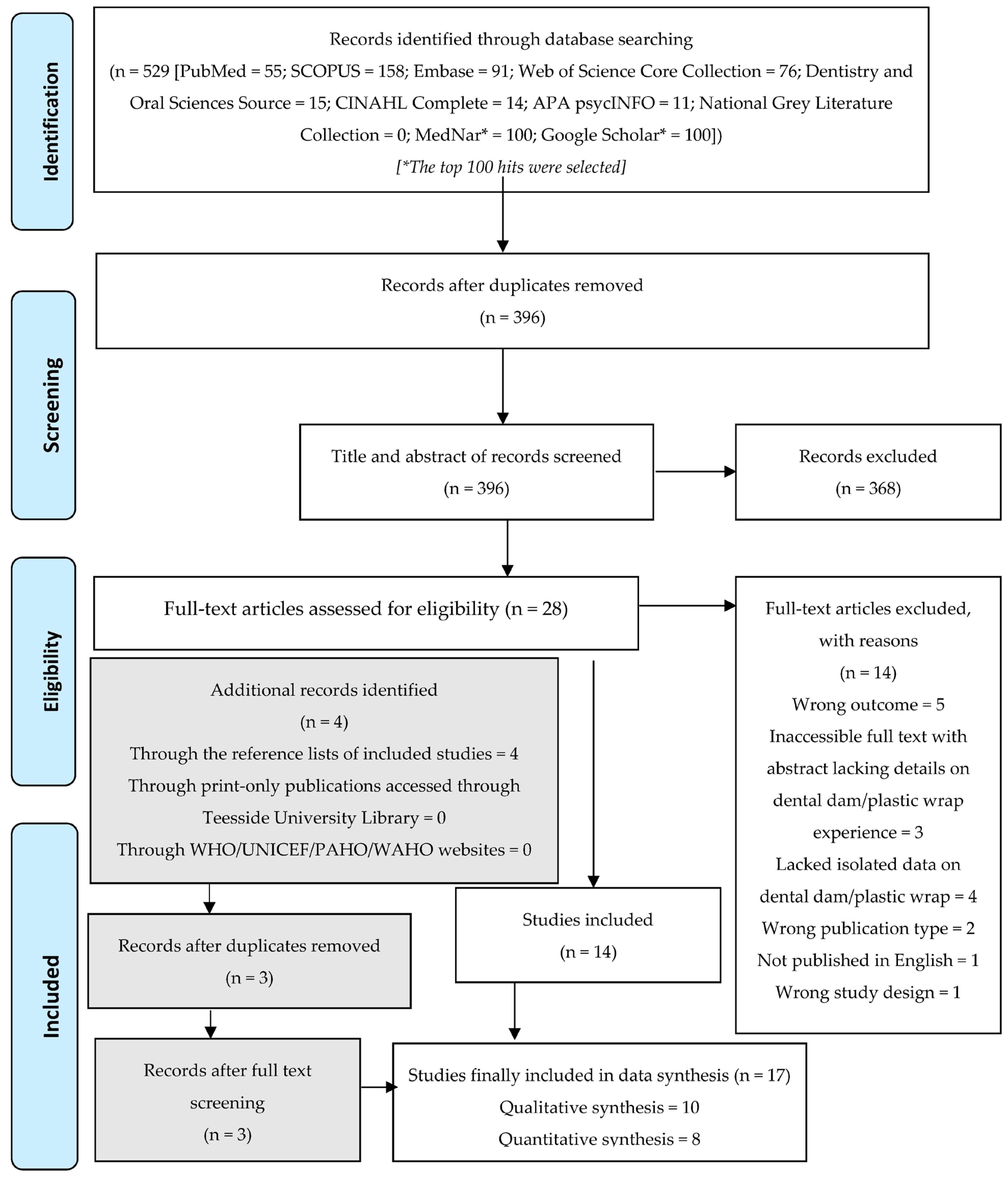

3.1. Literature Search Outcomes

3.2. Deduplication Outcomes

3.3. Literature Screening Outcomes

3.3.1. Electronic Databases

3.3.2. Other Sources

3.4. Quality Appraisal Outcomes

3.5. Synthesised Findings

3.5.1. Summary of Characteristics of the Included Literature

Study Design

Studied Population

Study Setting

3.5.2. Quantitative Synthesis

Knowledge of Dental Dams/Cling Film

Attitudes toward Dental Dams/Cling Film

Practices Concerning Dental Dam/Cling Film Use

Frequency of Use

Factors Influencing Use

Sociodemographic Factors

Sexual Behaviours

Knowledge

Drug Influence

Communication Skills

Effects of Dental Dam/Cling Film Use

3.5.3. Qualitative Synthesis

Theme 1: Knowledge of Dental Dams/Cling Film

| No. | Author(s) (Year) | Qualitative Study Design | Country; Settings | Sample and Participants’ Characteristics | Data Collection; Analysis | Study Objectives | Barriers Identified/Investigated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental Dam | Cling Film | |||||||

| 1 | Krienert et al. (2014) [77] | Secondary data analysis design | United States; correctional institutions | 900 participants—30 participants per prison facility, across 30 correctional institutions in 10 states; age and other sociodemographic features were not described | Secondary data; thematic analysis | To examine the attempts of inmates toward having safe sex | No | Yes |

| 2 | Craig Rushing and Gardner (2016) [83] | Multiple qualitative research designs | United States; community- and health facility-based | Phase 1 (the relevant phase): 30 participants—7 urban males, 7 tribal males, 7 urban females, 7 tribal females, and 7 LGBT-TS (lesbians, gays, bisexuals, trans, and two spirit); age and other sociodemographic features were not described | Focus groups and key informant interviews; analysis approach was not provided | To design a video-based STI/HIV intervention for heterosexuals and LGBT-TS | Yes | No |

| 3 | Grant and Nash (2018) [74] | Qualitative interview design informed by feminist methodological principles | Tasmania, Australia; Community-based | 15 participants; all were lesbian, bisexual, or queer women, based on sexual orientation, and aged 19 to 26 years; 86% were white, university educated, and middle class; 80% lived in the urban areas of Southern Tasmania | Semi-structured in-depth interviews using the feminist approach; thematic analysis | To investigate how lesbian, bisexual, and queer women in rural Australia construct meaning concerning safe sex and how they rationalise risks and safety with their sexual partners | Yes | No |

| 4 | Mahon (1996) [79] | Qualitative study—focus group design | United States; New York State prisons and New York City jails | 50 female participants—22 were former prisoners, 28 were inmates; 80% were aged ≤39 years; 28% had finished grade school; 32% were African Americans; 71% had been imprisoned at least twice | Focus groups; data analysis approach not identified | To evaluate the perceptions of inmates in New York State prisons and New York City jails on high-risk sexual behaviours | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Emetu et al. (2022) [70] | Qualitative study—telephone interview design | United States; Dinah Shore—a festival for lesbian and bisexual women in Palm Springs, California (United States) (community-based) | 19 participants—13 and 6 were lesbians and bisexual females, respectively; aged 22 to 43 years; 63% were single; half were White | Telephone interview aided by a question guide; thematic analysis | To explore the current sexual behaviours of women who have sex with women, and to examine the current protective methods they use to prevent sexually transmitted infection | Yes | No |

| 6 | Yap et al. (2010) [88] | Mixed-methods research design (Qualitative part adopted an in-depth face-to-face interview design) | Australia; New South Wales prison- and community-based settings | 19 participants—10 were inmates; 9 were ex-prisoners; all were females aged 19 to 50 years; 12 (63.2%) had served prison terms at least thrice; 5 (2.6%) were Aboriginal | Face-to-face in-depth interviews; thematic analysis | To examine the consensual practices among women imprisoned in New South Wales prisons with a focus on dental dams | ||

| 7 | Marrazzo, Coffey and Bingham (2005) [94] | Qualitative study—focus group discussion design | United States; greater Seattle metropolitan area (community-based) | 23 participants; all were females aged 18 to 29 years; 18 were White | 4 focus group discussions; thematic analysis | To explore the sexual practices among women who have sex with women, and to identify the most acceptable and most likely-to-practice protective behaviours amongst them | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Muzny et al. (2013) [81] | Qualitative study—focus group discussion design | United States; health facility and community settings in Birmingham | 29 participants—all were African American women who had sex with women | 7 focus group discussions; analysis approach was not provided | To explore the perception of safer sex and the risk of sexually transmitted infections among African American women who had sex with women | Yes | No |

| 9 | Doull et al. (2018) [69] | Qualitative study—focus group discussion design | United States; Online setting | 160 participants—all were lesbians/bisexuals aged 14 to 18 years; 52% were White; 20% were from the West | 8 focus group discussions; thematic analysis approach | To explore the participants’ choices of barrier use in sex | Yes | No |

| 10 | Gomez et al. (2014) [73] | Qualitative study—in-depth one-on-one interview design | United States; community- and health facility-based | 25 participants—all were adolescent African American men who have sex with men; all were aged between 15 and 19 years | In-depth one-on-one interview design; categorical and contextualising analytic methods | To explore the behaviours of adolescent African American men who have sex with men during their first same-sex sexual experiences | Yes | No |

| No. | Meta-Aggregation Stages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracted Finding (Relevant to Dental Dams or Plastic Wrap) [First Step] | Category [Second Step] | Synthesised Finding [Third Step] | ||

| Findings (F) | Supporting Quotes | |||

| Theme 1—Knowledge of Dental Dams/Cling Film | ||||

| F1 | “Misperceptions regarding protective barrier methods were common, exemplified by over half of the participants. Many women claimed familiarity with dental dams, though further questioning revealed confusion as to what dental dams are and how they are used. Most notable was the conflation of dental dams and female condoms. A few women spoke of using female condoms when performing oral sex on female partners but their descriptions indicated they were actually referring to dental dams…” (Muzny et al. (2013) [81] (p. 139)); [Unequivocal] | “Ours is square” “This [barrier method] is [on] the outside, pretty much like a box of paper [gesturing to indicate a 4-inch square].” “I know…like you said, you’re all talking about a dental dam. I’m under the impression that that’s the female condom, [so I] didn’t know the difference. I never knew how to use them. I mean it was showed to me, but I didn’t know…I thought they were the same thing…” | Knowledge of Dental Dams | Knowledge of Dental Dams/Cling Film |

| F2 | “Even those familiar with the concept of barriers for sex with male partners shared that they were unaware of dental dams or of where to find them.” (Doull et al. (2018) [69] (p. 413)); [Unequivocal] | “Barriers aren’t really available for lesbians. Like where the heck do you buy dental dams?” “I didn’t even know dental dams were even a thing,” “I’ve never used barriers, I honestly did not know that was an option during girl-on-girl sex until maybe a year ago.” | ||

| F3 | “Lack of knowledge about safer sexual practices when engaging in sexual activity with women extended to dental dams, which three participants had never heard about.” (Emetu et al. (2022) [70] (p. 9)); [Equivocal] | “Definitely something better than dental dams. They’re super awkward and hard to use and just really poorly constructed, so if there was some sort of barrier that was easier to use on a woman, I think, would go a long way.” (#101, Northeastern Middle Eastern lesbian, age 34). | ||

| F4 | “Youth who described oral-anal sex described non-use because of lack of knowledge of dental dams.” (Gomez et al. (2014) [73] (p. S4)) [Unsupported] | |||

| Theme 2—Attitudes toward Dental Dams/Cling Film | ||||

| Theme 2: Sub-Theme 1 | Attitudes toward Dental Dams/Cling Film | |||

| F5 | “Many expressed a belief that dental dams were “silly” and that they couldn’t imagine asking a sexual partner to use one.” (Craig Rushing and Gardner, (2016) [83] (p. 35)); [Unsupported] | General perception of Dental Dams | ||

| Theme 2: Sub-Theme 2 | ||||

| F6 | “Discussions in all groups included the idea of using STI testing as a safe-sex strategy. Girls, especially inexperienced ones, explained that STI testing, as a couple, could effectively manage their risk.” (Doull et al. (2018) [69] (p. 413)); [Equivocal] | “I know I should use barriers even with girls, but I’d also prefer if I could be tested and my partner could be tested. If we’re clean, I’d much rather go without any barriers.” (17-year-old experienced lesbian) “I would much rather just have both of us be tested for STDs than use a dental dam. I feel like it would be uncomfortable and ruin the mood.” (14-year-old inexperienced lesbian) | Preference for Other Protective Measures | |

| Theme 2: Sub-Theme 3 | ||||

| F7 | “Others preferred to have sex without dental dams since they saw it as more ‘natural’ or they perceived their partners not to be at risk” (Yap et al. (2010) [88] (p. 173)); [Unequivocal] | “No, because I haven’t really, like I said, only the one person [her current partner] that I’d ever [sleep with], you know. And I was comfortable enough with her to [not use dental dams], you know, she’s anally clean [not promiscuous], you know.” (Female prisoner, 25 years) | Poor Perception of the Risk of Contracting Sexually Transmitted Infections | |

| Theme 2: Sub-Theme 4 | ||||

| F8 | “Of the 16 participants who knew what dental dams were, only two claimed to have tried them during oral sex. Participants expressed aversion and displeasure for the product. The interviewees used terms such as “awkward,” “unsexy,” and “not user-friendly” to describe their experiences with this barrier method.” (Emetu et al. (2022) [70] (p. 9)); [Unequivocal] | “Definitely something better than dental dams. They’re super awkward and hard to use and just really poorly constructed, so if there was some sort of barrier that was easier to use on a woman, I think, would go a long way.” (#101, Northeastern Middle Eastern lesbian, age 34). | Previous Experience with Dental Dam Use | |

| F9 | “Women, even the few regular users of dental dams, reported that they did not like the taste or feel of the dental dams from the vending machines. They found that they tasted powdery, plastic or rubbery; were not flavoured; and were too thick or dry, reducing sexual sensations during oral sex” (Yap et al. (2010) [88] (p. 173)); [Unequivocal] | “They taste terrible. I’ve put it up in my mouth, and sucked it in and fucked around with it. It tastes funny. Powdery plastic shit. They’re not flavoured.” (Female prisoner, 26 years) “No, generally people just gig the dental dams, because they’re plastic, and, you know, if you’re going down on someone, you know, your tongue’s [on her], they’ll feel the pressure of your tongue but there’s no wetness there, and it sort of kills the whole thing.” (Female prisoner, 28 years) “But a couple of the girls that I’ve shown have used them, and it was also them that said, “They’re too thick; you can’t feel anything through them,” you know. I agree with them; they are thick, these ones. It’s like there’s about five of them together, because they’re that thick.”(Female prisoner, 35 years) | ||

| Theme 2: Sub-Theme 5 | ||||

| F10 | “When prompted that using condoms on sex toys can be a safe-sex practice, individuals among both the inexperienced bisexual and lesbian groups responded that they would consider using dental dams or a condom.” (Doull et al. (2018) [69] (pp. 412–413)); [Unsupported] | Attitudes toward the Future Use of Dental Dams | ||

| F11 | “Participants, especially those who identifying as inexperienced, seemed open to using barriers in the future.” (Doull et al. (2018) [69] (p.413)); [Unequivocal] | “I’ve literally never heard of dental dams but like I said before, I’m so paranoid about STDs that I’m fine with whatever prevention is possible.” (14-year-old inexperienced lesbian) “I think for the most part, it’s a good idea to always use barriers because even if someone thinks they’re clean, they might have an STD.”(17-year-old inexperienced lesbian) | ||

| Theme 3—Practices concerning Dental Dam/Cling Film Use | ||||

| Theme 3: Sub-Theme 1 | Practices concerning Dental Dam/Cling Film Use | |||

| F12 | “Of the 16 participants who knew what dental dams were, only two claimed to have tried them during oral sex.” (Emetu et al. (2022) [70] (p. 9); [Unsupported] | Frequency of Dental Dam Use | ||

| F13 | “Although several WSW identified dental dams as a way to prevent STIs, none reported having used them.” (Craig Rushing and Gardner (2016) [83] (p. 35)); [Unsupported] | |||

| F14 | “None of the participants report using barrier methods recommended for preventing fluid exchange between women (e.g., dental dams, gloves) and only three considered using them in the future:” (Grant and Nash (2018) [74] (p. 313)); [Unequivocal] | “I only found out about dental dams recently, so, um, yeah, I’ve never used them and…I don’t really think I would. They seem a bit…gross, really. Not something I would (laughing) purchase!”(Carrie, 23, bisexual) That kind of thing hasn’t ever really come up with girls. Like, how would I…? I don’t know what I’d say…No. Nup. They’d just take all the fun away. I was given [a dental dam] at [a queer event] once and I read about what it was and I was like, cool, but I’m not using one of these—straight in the bin (laughs).” (Stella, 25, bisexual) | ||

| F15 | “Participants mentioned that their peers were not using dental dams and desired a better alternative.” (Emetu et al. (2022) [70] (p. 10)); [Unequivocal] | “I never heard anyone use them [dental dams]. Like my friends, I never heard of anyone saying they use it.”(#102, Western Asian lesbian, age 33) | ||

| F16 | “Two women interviewed who had had same-sex encounters in prison had used dental dams, either as a one-off or as a regular practice with casual partners.” (Yap et al. (2010) [88] (p. 173)); [Unequivocal] | “But I’ve always used dams, especially on, as I was saying, women that I’ve only known for a couple of weeks; or on the two or three occasions where I have slept with someone on the first time of seeing and meeting them, I’ve used them as well.” (Female prisoner, 35 years) | ||

| F17 | “Participants generally agreed that use of barrier methods, including dental dams and plastic wrap, to cover the genitals is not a common approach to reducing the risk of STD transmission with oral sex.” (Marrazzo, Coffey and Bingham (2005) [94]); [Unsupported] | |||

| Theme 3: Sub-Theme 2 | ||||

| F18 | “Although less common, safe sex practices were also revealed in female inmate narratives.” (Krienert et al. 2014) [77] (p. 395)); [Unequivocal] | “Some will use saran wrap, you can buy it if someone steals it from the kitchen. People are worried about disease and most will take precautions.” “they say they put saran wrap on it and protect themselves, [if] they have AIDS.” | Reason for the Use: Protection against Infections | |

| Theme 3: Sub-Theme 3 | ||||

| F19 | “LGBT-TS youth reported that accessing condoms was relatively easy and free at clinics, nonprofit organizations, and events for queer youth; however, those seeking dental dams and gloves were often hard pressed to find these forms of protection.” (Craig Rushing and Gardner (2016) [83] (p. 35)); [Unsupported] | Access to Dental Dams or Cling Film | ||

| F20 | “Without any access to condoms or dental dams, participants described home-made devices that they had used in state prison to practice safer sex, including plastic gloves and plastic wrap stolen from the kitchen.” (Mahon (1996) [79] (p. 1213)); [Unequivocal] | “Half of the time they’re [inmates] not really finding no Saran Wrap, and if they’re finding Saran Wrap, they are taking that Saran Wrap and using it over and over and over again”(Transcript of focus group of female former state inmates, November 1993, pp. 49–50 [hereinafter “Women’s State”]) | ||

| F21 | “Several female participants commented that in light of the frequency of sexual relations with male correctional officers, female prisoners should have access to condoms as well as dental dams.” (Mahon (1996) [79] (p. 1213)); [Unsupported] | |||

| F22 | “The accessibility of dental dams was problematic for some participants. Many stated that finding and purchasing them was difficult, even though male condoms could be purchased anytime at drug stores. Some stated that dental dams were accessible only online or in adult stores. Some participants had never seen a dental dam outside its packaging.” (Emetu et al. (2022 [70] (p. 10)); [Unequivocal] | “I’ve never used one [dental dams] and I don’t think I’ve ever even seen one at, like, a pharmacy, where they have the condom section. I don’t believe I’ve seen dental dams. I mean, I honestly have not looked for them, but obviously when you go through one of the aisles, you can tell, “Okay. I see condoms right there,” loud and clear. But I have not come across the dental dams at any store.” (#111, Western White lesbian, age 35) | ||

| F23 | “Some participants highlighted the differential accessibility of female and male barrier methods. Some stated that men’s use of condoms was much more normalized and common than women’s use of dental dams or finger cots” (Emetu et al. (2022 [70] (p. 10)); [Equivocal] | “When you go anywhere, Pride or whatever, they like, throw out condoms but they never give you finger condoms. That could be a thing where if you gave people finger condoms, they might actually use them and then be like, “Oh, we’re having sex on the first date. Maybe I should use the finger condom.” (#108, Northeastern Black lesbian, age 30) | ||

| F24 | “Most women interviewed said that dental dams were available to them in prison, although two women reported that they had heard of but had never seen a dental dam while incarcerated…Our observations in one prison found that one dispensing machine was filled with dental dam kits but the box had become wet from the rainy weather as the vending machine was located outside a residential prison block. Another vending machine in a segregated unit of a women’s prison was empty.” (Yap et al. (2010 [88] (p. 173)); [Unequivocal] | “One said, ‘Oh yeah, I know what they are. No, never took one” (ex-prisoner, 24 years) “Another woman reported that dispensing machines had not been filled in a long time or were quickly emptied” (ex-prisoner, 38 years) | ||

Theme 2: Attitudes toward Dental Dams/Cling Film

Sub-Theme 1: General Perception of Dental Dams

Sub-Theme 2: Preference for Other Protective Measures

Sub-Theme 3: Poor Perceptions of the Risk of Contracting Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sub-Theme 4: Previous Experience with Dental Dam Use

Sub-Theme 5: Attitudes toward the Future Use of Dental Dams

Theme 3: Practices Concerning Dental Dam/Cling Film Use

Sub-Theme 1: Frequency of Dental Dam Use

Sub-Theme 2: Reason for Use: Protection against Infections

Sub-Theme 3: Access to Dental Dams or Cling Film

Configuration of Synthesised Data

Knowledge

Attitudes

Practices

4. Discussion

4.1. Population Characteristics

4.2. Knowledge of Cling Film and Dental Dams

4.3. Attitudes toward Cling Film and Dental Dams

4.4. Practices Concerning the Use of Cling Film and Dental Dams

4.5. Effects of Cling Film and Dental Dam Use

4.6. Limitations of the Study

4.7. Strengths of the Study

4.8. Indications for Further Research

4.9. Public Health and Policy Recommendations

- Robust and strategic public health research on all forms of protective sex barriers and domains of evidence (including knowledge, attitudes, and practices), especially on dental dams and cling film, should be performed, as it will provide further evidence that will help in tackling the non-abating global burden of STIs [25].

- Public policies that will improve public access to, and knowledge of, the sexual use (including self-efficacy) of dental dams and cling film should be formulated and implemented. Pertinently, the policies should be all-inclusive, favouring both the privileged and disadvantaged populations (such as prisoners, HIV patients, etc.), and they should be applied at all tiers.

- Massive health education campaigns should be implemented to inform the public about the health benefits of protected oral sex and dental dam/cling film use.

- Further research, especially experimental studies, should be conducted to determine the level of efficacy of dental dams in reducing the transmission of sexually transmitted oral infections.

- The manufacturers and suppliers of dental dams should improve the quality of dental dams sold to the public. Importantly, user manuals should be included in the product packets, and the taste, texture, and appearance of dental dams should be made more appealing without altering their functional integrity.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, T.; Puri, G.; Aravinda, K.; Arora, N.; Patil, D.; Gupta, R. Oral sex and oral health: An enigma in itself. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2015, 36, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.; Malic, V.; Fu, T.-C.; Paul, B.; Zhou, Y.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Herbenick, D. Porn Sex versus Real Sex: Sexual Behaviors Reported by a U.S. Probability Survey Compared to Depictions of Sex in Mainstream Internet-Based Male–Female Pornography. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellington, T.D.; Henley, S.J.; Senkomago, V.; O’Neil, M.E.; Wilson, R.J.; Singh, S.; Thomas, C.C.; Wu, M.; Richardson, L.C. Trends in Incidence of Cancers of the Oral Cavity and Pharynx—United States 2007–2016. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylie, K. A Global Survey of Sexual Behaviours. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2009, 3, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, E.S.; Vasilenko, S.A.; Leavitt, C.E. Oral vs. Vaginal Sex Experiences and Consequences Among First-Year College Students. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 45, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Tanton, C.; Mercer, C.H.; Mitchell, K.R.; Palmer, M.; Macdowall, W.; Wellings, K. Heterosexual Practices Among Young People in Britain: Evidence from Three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2017, 61, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhason-Bello, I.O.; Kabakama, S.; Baisley, K.; Francis, S.C.; Watson-Jones, D. Reported oral and anal sex among adolescents and adults reporting heterosexual sex in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD Risk and Oral Sex—CDC Fact Sheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/healthcomm/stdfact-stdriskandoralsex.htm#:~:text=Oral%20sex%20involves%20using%20the%20mouth%2C%20lips%2C%20or,are%20also%20called%20the%20genitals%20or%20genital%20area (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Plüddemann, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Mathews, C.; Carney, T.; Lombard, C. Adolescent methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviour in secondary school students in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 27, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, W.; Pals, S.L.; McLellan-Lemal, E.; Shinde, S.; Nyambura, M.; Otieno, F.O.; Gust, D.A.; Chen, R.T.; Thomas, T. Baseline Findings of an HIV Incidence Cohort Study to Prepare for Future HIV Prevention Clinical Trials in Kisumu, Kenya. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2012, 6, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpahan, C.; Darmadi, D.; Agustinus, A.; Rezano, A. Framing and understanding the whole aspect of oral sex from social and health perspective: A narrative review. F1000Research 2022, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmodi, K.K.; Nwafor, J.N.; Amoo, B.A.; Nnyanzi, L.A.; Ogbeide, M.E.; Hundeji, A.A. Knowledge of the Health Implications of Oral Sex among Registered Nurses in Nigeria: An Online Pilot Study. J. Health Allied Sci. NU 2022, 13, 046–052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Blas, M.M.; Cabral, A.; Carcamo, C.; Gravitt, P.E.; Halsey, N. Oral sex practices, oral human papillomavirus and correlations between oral and cervical human papillomavirus prevalence among female sex workers in Lima, Peru. Int. J. STD AIDS 2011, 22, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherie, A.; Berhane, Y. Oral and anal sex practices among high school youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathece, L. Prevalence of oral sex and wet kissing among femal sex workers in two areas of Nairobi, Kenya. Afr. J. Oral Health Sci. 2004, 1, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shen, S.; Hsieh, N. A National Dyadic Study of Oral Sex, Relationship Quality, and Well-Being among Older Couples. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 74, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern-Felsher, B.L.; Cornell, J.L.; Kropp, R.Y.; Tschann, J.M. Oral Versus Vaginal Sex Among Adolescents: Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behavior. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; John, H.K.S.; Garcia, J.; Lloyd, E.A. Differences in Orgasm Frequency Among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Men and Women in a U.S. National Sample. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 47, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelman, C.A.; Coumans, A.B.; Nijman, H.W.; Doxiadis, I.I.; Dekker, G.A.; Claas, F.H. Correlation between oral sex and a low incidence of preeclampsia: A role for soluble HLA in seminal fluid? J. Reprod. Immunol. 2000, 46, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittrof, R.; Sully, E.; Bass, D.C.; Kelsey, S.F.; Ness, R.B.; Haggerty, C. Stimulating an immune response? Oral sex is associated with less endometritis. Int. J. STD AIDS 2012, 23, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, T.; Baden, N.; Haasnoot, G.; Wagner, M.; Dekkers, O.; le Cessie, S.; Picavet, C.; van Lith, J.; Claas, F.; Bloemenkamp, K. Oral sex is associated with reduced incidence of recurrent miscarriage. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019, 133, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.; Saini, S.; Sharma, S. Oral sex, oral health and orogenital infections. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacad, B.L.; Hess, G.C. Oral sex: Behaviours and feelings of Canadian young women and implications for sex education. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2010, 15, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilenko, S.A.; Maas, M.K.; Lefkowitz, E.S. “It felt good but weird at the same time”: Emerging adults’ first experiences of six different sexual behaviors. J. Adolesc Res. 2015, 30, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Smith, D.K.; Herbst, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Rose, C.E. Condom Effectiveness for HIV Prevention by Consistency of Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J.; Rosen, J.E.; Carvalho, M.N.; Korenromp, E.L.; Friedman, H.S.; Cogan, M.; Deperthes, B. The case for investing in the male condom. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, C.; Tsoumanis, A.; Rotsaert, A.; Vuylsteke, B.; Van den Bossche, D.; Paeleman, E.; De Baetselier, I.; Brosius, I.; Laumen, J.; Buyze, J.; et al. Antibacterial mouthwash to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men taking HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PReGo): A randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet. Infec.t Dis. 2021, 21, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, J.; Prestage, G.; Schneider, K.; Clayton, S. Do women use dental dams? Safer sex practices of lesbians and other women who have sex with women. Sex. Health 2010, 7, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoun, D. Méthodes de contraception naturelle et méthodes barrières. RPC contraception CNGOF [Natural Family Planning methods and Barrier: CNGOF Contraception Guidelines]. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2018, 46, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planned Parenthood. STD Awareness: Can I Use Plastic Wrap as a Dental Dam During Oral Sex? 2016. Available online: https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/planned-parenthood-advocates-arizona/blog/std-awareness-can-i-use-plastic-wrap-as-a-dental-dam-during-oral-sex (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Gallo, M.F.; Kilbourne-Brook, M.; Coffey, P.S. A review of the effectiveness and acceptability of the female condom for dual protection. Sex. Health 2012, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthline. Tongue Condoms: What You Need to Know. 2019. Available online: https://www.healthline.com/health/tongue-condom (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- National Health Service. Condoms: Your Contraceptive Guide. 2020. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/contraception/male-condoms/ (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Weller, S.C.; Davis-Beaty, K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 2012, CD003255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Dam Use. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/Dental-dam-use.html (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Newman, L.; Rowley, J.; Hoorn, S.V.; Wijesooriya, N.S.; Unemo, M.; Low, N.; Stevens, G.; Gottlieb, S.; Kiarie, J.; Temmerman, M. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Yu, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lan, L.; Yang, S.; Wu, J. Global burden and trends of sexually transmitted infections from 1990 to 2019: An observational trend study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 22, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-López, C.; Morales-Angulo, C. Otorhinolaryngology manifestations secondary to oral sex. Lesiones otorrinolaringológicas secundarias al sexo oral. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2017, 68, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habel, M.A.; Leichliter, J.S.; Dittus, P.J.; Spicknall, I.H.; Aral, S.O. Heterosexual Anal and Oral Sex in Adolescents and Adults in the United States, 2011–2015. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2018, 45, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J.; Teng, Y. The impact of condom use on the HIV epidemic. Gates Open Res. 2022, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Montori, V.M.; Del Mar, C. The Connection Between Evidence-Based Medicine and Shared Decision Making. JAMA 2014, 312, 1295–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, K.; Stapleton, J.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, A. Grey literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. J. Evid. Based Med. 2017, 10, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. What is a systematic review? Evid. Based Nurs. 2011, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustini, D.; Boulos, M.N.K. Google Scholar is not enough to be used alone for systematic reviews. Online J. Public Health Informatics 2013, 5, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Sarabi, R.E.; Orak, R.J.; Bahaadinbeigy, K. Information Retrieval in Telemedicine: A Comparative Study on Bibliographic Databases. Acta Inform. Medica 2015, 23, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.; Giustini, D.; De Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H.; Griffin, S.J.; Kuhn, I.; Usher-Smith, J. Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: An evaluation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist. University of Canberra Library; Flinders University, Adelaide. 2010. Available online: https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599348&p=4148869 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Daeganis, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/146002140/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-08c.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Clark, S.E.; Chisnall, G.; Vindrola-Padros, C. A systematic review of de-escalation strategies for redeployed staff and repurposed facilities in COVID-19 intensive care units (ICUs) during the pandemic. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 Edition; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M.; Voils, C.I.; Barroso, J. Defining and Designing Mixed Research Synthesis Studies. Research in the schools: A nationally refereed journal sponsored by the Mid-South Educational Research Association and the University of Alabama. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearson, A.; White, H.; Bath-Hextall, F.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.L.A.; Kirkpatrick, P. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Health 2015, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, E.E.; Tutton, E.; Griffin, X.; Baird, J. A mixed-methods systematic review of patients’ experience of being invited to participate in surgical randomised controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 253, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Ho, S.G.W. Cooties and Love Gloves: Relational Contexts of Sexual Health Decisions. Doctoral Dissertation, Adler University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin, E.M.; Hannan, M.; Walsh, J.; Talboys, C.; Shah, D.; Flynn, R.; Azadian, B.S.; Boag, F.C. Nasopharyngeal flora in HIV seropositive men who have sex with men. Genitourin. Med. 1997, 73, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrezia, M.; Baker, D.; McDowell, I. Testing for Turkeys Faith-Based Community HIV Testing Initiative: An Update. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2018, 29, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Spear, M.E. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and perceived barriers to vaccination in a sample of US female college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 59, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doull, M.; Wolowic, J.; Saewyc, E.; Rosario, M.; Prescott, T.; Ybarra, M.L. Why Girls Choose Not to Use Barriers to Prevent Sexually Transmitted Infection During Female-to-Female Sex. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emetu, R.E.; Hernandez, E.N.; Calleros, L.; Missari, S. Sexual behaviors of women who have sex with women: A qualitative explorative study. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2022, 35, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.L.; Fairley, C.K.; Greaves, K.E.; Vodstrcil, L.A.; Ong, J.J.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Chen, M.Y.; Phillips, T.R.; Chow, E. Patterns of Sexual Practices, Sexually Transmitted Infections and Other Genital Infections in Women Who Have Sex with Women Only (WSWO), Women Who Have Sex with Men Only (WSMO) and Women Who Have Sex with Men and Women (WSMW): Findings from a Sexual Health Clinic in Melbourne, Australia, 2011–2019. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 2651–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Llario, M.D.; Morell-Mengual, V.; García-Barba, M.; Nebot-García, J.E.; Ballester-Arnal, R. HIV and STI Prevention Among Spanish Women Who have Sex with Women: Factors Associated with Dental Dam and Condom Use. AIDS Behav. 2022, 27, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, M.; Ogunbajo, A.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Trent, M.; Arrington-Sanders, R. The use of condoms and dental dams during first same-sex sexual experiences (SSE) of adolescent African-American men who have sex with men. J. Adolesc. Health. 2014, 54, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.; Nash, M. Navigating unintelligibility: Queer Australian young women’s negotiations of safe sex and risk. J Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, W.E.; Gray, C.; Hawkins, W.E. Gender differences of reported safer sex behaviors within a random sample of college students. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77 Pt 1, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerhofer, V.; Kofler, B.; Riechelmann, H. High-Risk-HPV-Infektionen im Kopf-Hals-Bereich—Welche Bedeutung hat das Sexualverhalten? Laryngorhinootologie 2020, 99, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krienert, J.; Walsh, J.; Lech, L. Alternatives to abstinence: The practice of (un)safe sex in prison. Crim. Justice Stud. 2014, 27, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBride-Stewart, S. Dental dams: A parody of straight expectations in the promotion of safer lesbian sex. In Out in the Antipodes: Australian and New Zealand Perspectives on Gay and Lesbian Issues in Psychology; Brightfire Press: Perth, WA, Australia, 2004; pp. 368–391. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, N. New York inmates’ HIV risk behaviors: The implications for prevention policy and programs. Am. J. Public Health. 1996, 86, 1211–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool-Myers, M.; Myo, A.; Carter, J.A. Barriers to Purchasing Condoms in a High HIV/STI-Risk Urban Area. J. Commun. Health 2019, 44, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzny, C.A.; Harbison, H.S.; Pembleton, E.S.; Hook, E.W.; Austin, E.L. Misperceptions regarding protective barrier method use for safer sex among African-American women who have sex with women. Sex. Health 2013, 10, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, J.R.; Mshana, G.; Kaatano, G.; Changalucha, J. “Half plate of rice to a male casual sexual partner, full plate belongs to the husband”: Findings from a qualitative study on sexual behaviour in relation to HIV and AIDS in northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig Rushing, S.; Gardner, W. Native VOICES: Adapting a video-based sexual health intervention for American Indian teens and young adults using the ADAPT-ITT model. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salyer, D. An Oral Examination; Survival News: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1998; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, L.; Bond, C.; Gault, C. A survey of pharmacy assistants in Grampian on prevention of HIV and hepatitis B and C. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2006, 14, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Bond, C.; Gault, C. A survey of community pharmacists on prevention of HIV and hepatitis B and C: Current practice and attitudes in Grampian. J. Public Health Med. 2003, 25, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, L.; Butler, T.; Richters, J.; Kirkwood, K.; Grant, L.; Saxby, M.; Ropp, F.; Donovan, B. Do condoms cause rape and mayhem? The long-term effects of condoms in New South Wales’ prisons. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2007, 83, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, L.; Richters, J.; Butler, T.; Schneider, K.; Kirkwood, K.; Donovan, B. Sexual practices and dental dam use among women prisoners—A mixed methods study. Sex Health. 2010, 7, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Rosario, M.; Saewyc, E.; Goodenow, C. Sexual Behaviors and Partner Characteristics by Sexual Identity Among Adolescent Girls. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2016, 58, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappulla, A.; Fairley, C.K.; Donovan, B.; Guy, R.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Chen, M.Y.; Phillips, T.R.; Maddaford, K.; Chow, E.P.F. Sexual practices of female sex workers in Melbourne, Australia: An anonymous cross-sectional questionnaire study in 2017–2018. Sex. Health 2020, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collica, K. Prison conducts safer-sex workshop for women. AIDS Policy Law 1996, 11, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.V.; Farquhar, C.; Owen, C.; Whittaker, D. Sexual behaviour of lesbians and bisexual women. Sex Transm Infect. 2003, 79, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H. Sexual Norms for Lesbian and Bisexual Women in a Culture Where Lesbianism Is Not Acceptable Enough: The Japanese Survey About Sexual Behaviors, STIs Preventive Behaviors, and the Value of Sexual Relations. J. Homosex. 2019, 66, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrazzo, J.M.; Coffey, P.; Bingham, A. Sexual practices, risk perception and knowledge of sexually transmitted disease risk among lesbian and bisexual women. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 2005, 37, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, T.; Maher, D.; Nyirenda, T.; Olesen, O.F. Strengthening health research capacity in sub-Saharan Africa: Mapping the 2012–2017 landscape of externally funded international postgraduate training at institutions in the region. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndinda, C.; Uzodike, U.O.; Chimbwete, C.; Mgeyane, M.T.M. Gendered Perceptions of Sexual Behaviour in Rural South Africa. Int. J. Fam. Med. 2011, 2011, 973706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.; Salmon, C.; Burch, R. Female Provision of Oral Sex. In The Cambridge Handbook of Evolutionary Perspectives on Sexual Psychology; Shackelford, T., Ed.; Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adohinzin, C.C.Y.; Méda, N.; Belem, A.M.G.; Ouédraogo, G.A.; Berthé, A.; Sombié, I.; Avimadjenon, G.D.; Diallo, I.; Fond-Harmant, L. Utilisation du préservatif masculin: Connaissances, attitudes et compétences de jeunes burkinabè. Sante Publique 2017, 29, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etowa, J.; Ghose, B.; Loemba, H.; Etowa, E.B.; Husbands, W.; Omorodion, F.; Luginaah, I.; Wong, J.P.-H. Factors Associated with Condom Knowledge, Attitude, and Use among Black Heterosexual Men in Ontario, Canada. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 8862534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallie, P.D.; Haffejee, F. Systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the knowledge and use of the female condom among Nigerians. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenny, S.; Brannan, G.D.; Brannan, J.M.; Sharts-Hopko, N.C. Qualitative Study. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, E.P.F.; Williamson, D.A.; Hocking, J.S.; Law, M.G.; Maddaford, K.; Bradshaw, C.S.; McNulty, A.; Templeton, D.J.; Moore, R.; Murray, G.L.; et al. Antiseptic mouthwash for gonorrhoea prevention (OMEGA): A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnes, J.-N.; Marchal-Sixou, C.; Nabet, C.; Maret, D.; Hamel, O. Ethics in systematic reviews. J. Med. Ethics 2010, 36, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, R. Human sexual response. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 130, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICO Framework | Search String |

|---|---|

| Population | No need for a search string on this because all population groups are included |

| Intervention (or Exposure) | ‘sex’ OR ‘coitus’ OR ‘intercourse’ OR ‘oral sex’ OR ‘fellatio’ OR ‘cunnilingus’ OR ‘anilingus’ [field search: title, abstracts, and keywords] |

| ‘dental dam’ OR ‘rubber dam’ [field search: title, abstracts, and keywords] | |

| ‘plastic wrap’ OR ‘cling film’ OR ‘cling wrap’ OR ‘clingwrap’ OR ‘polythene wrap’ OR ‘food wrap’ OR ‘saran wrap’ OR ‘glad wrap’ OR ‘gladwrap’ OR ‘cellophane’ [field search: title, abstracts, and keywords] | |

| Comparison (or Context) | No need for a search string on this because all comparisons are included |

| Outcome | No need for a search string on this because all outcomes with no restriction are in the focus of the study |

| Items | Exclusion Criteria | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Animal species | All populations of humans without restriction to race, ethnicity, gender, religion, socioeconomic class, age, creed or orientation |

| Intervention (or exposure/interest) | (1) Literature investigating the experiences (with focus on knowledge, attitudes, practices, or effectiveness) concerning the use of other physical barriers (genital condoms (male and female condoms) and/or tongue condoms) in oral sex only. (2) Literature on cling film and/or dental dams that did not investigate their association with oral sexual activity | Literature investigating the experiences (with focus on knowledge, attitudes, practices, effects, or effectiveness) of cling film or dental dam use in oral sex |

| Comparison (for intervention studies only) | Literature reporting only the effects and/or effectiveness of use of other physical barriers (genital condoms (male and female condoms) and/or tongue condoms) in oral sex | Literature reporting the effects and/or effectiveness of cling film and/or dental dam use in oral sex |

| Outcomes | For interventional studies: Literature reporting the effects and/or effectiveness of other physical barriers (genital condoms (male and female condoms) and/or tongue condoms) in oral sex. For non-interventional studies: Literature that did not report the experiences (knowledge, attitudes, or practices) concerning the use of cling film and dental dams in oral sex | For intervention studies: Literature reporting the effects and/or effectiveness of cling film and/or dental dam use in oral sex. For non-intervention studies: Literature reporting the experiences concerning cling film and dental dam use in oral sex. These experiences include knowledge, attitudes, or practices |

| Study (literature) type | Editorials, correspondence (letters), bibliometric reviews, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, and any other non-empirical study | Grey and non-grey empirical studies such as cross-sectional studies (surveys and qualitative studies), before-and-after studies, case–control studies, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, qualitative studies, quantitative studies, and mixed-methods studies |

| Language of publication | Literature published in German, French, Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, or any other language except English | Literature published in English |

| Full text accessibility | Literature having inaccessible full texts, i.e., those studies that could not be obtained within two weeks from the corresponding author or Teesside University’s Interlibrary Loan | Literature having accessible full texts |

| No. | Citation | Included | Excluded (Reasons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [65] | Yes (Inaccessible full text with abstract lacking details on dental dam/plastic wrap experience) | |

| 2 | [66] | Yes | |

| 3 | [67] | Yes (Wrong outcome, wrong study design, wrong publication type) | |

| 4 | [68] | Yes (Lacked isolated data on dental dams/plastic wrap) | |

| 5 | [69] | Yes | |

| 6 | [70] | Yes | |

| 7 | [71] | Yes (Lacked isolated data on dental dams/plastic wrap) | |

| 8 | [72] | Yes | |

| 9 | [73] | Yes | |

| 10 | [74] | Yes | |

| 11 | [75] | Yes (Lacked isolated data on dental dams/plastic wrap) | |

| 12 | [76] | Yes (Not published in English) | |

| 13 | [77] | Yes | |

| 14 | [78] | Yes (Inaccessible full text with abstract lacking details on dental dams/plastic wrap experience) | |

| 15 | [79] | Yes | |

| 16 | [80] | Yes (Wrong outcome) | |

| 17 | [81] | Yes | |

| 18 | [82] | Yes (Wrong outcome) | |

| 19 | [29] | Yes | |

| 20 | [83] | Yes | |

| 21 | [84] | Yes (Inaccessible full text with abstract lacking details on dental dams/plastic wrap experience) | |

| 22 | [85] | Yes (Wrong outcome) | |

| 23 | [86] | Yes (Wrong outcome) | |

| 24 | [87] | Yes | |

| 25 | [88] | Yes | |

| 26 | [89] | Yes (Lacked isolated data on dental dams/plastic wrap) | |

| 27 | [90] | Yes | |

| 28 | [91] | Yes (Wrong publication type) |

| No. | Citation |

|---|---|

| 1 | [92] |

| 2 | [93] |

| 3 | [94] |

| No. | Author(s) (Year) | Study Design | MMAT Version 2018 Questions (Hong et al., 2018) [57] | Total Score (Over 7) | Grading | Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Questions | Questions Specific to Study Design | |||||||||||

| S1 | S2 | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | ||||||

| 1 | Krienert et al. (2014) [77] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 2 | Yap et al. (2007) [87] | Qn | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 3 | Richters et al. (2010) [29] | QnR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 6 | Above average | Accept |

| 4 | Gil-Llario et al. (2022) [72] | QnR | Y | Y | I | Y | Y | N | Y | 5.5 | Above average | Accept |

| 5 | Carlin et al. (1997) [66] | QnR | Y | Y | I | Y | Y | N | Y | 5.5 | Above average | Accept |

| 6 | Craig Rushing and Gardner (2016) [83] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | N | Y | 5.5 | Above average | Accept |

| 7 | Grant and Nash (2018) [74] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 8 | Mahon (1996) [79] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 9 | Emetu et al. (2022) [70] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 10 | Bailey et al. (2003) [92] | Qn | Y | Y | Y | I | Y | Y | Y | 6.5 | Above average | Accept |

| 11 | Fujii (2019) [93] | QnR | Y | Y | I | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6.5 | Above average | Accept |

| 12 | Yap et al. (2010) [88] | MM | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 13 | Marrazzo, Coffey and Bingham (2005) [94] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 14 | Muzny et al. (2013) [81] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 15 | Zappulla et al. (2020) [90] | QnR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| 16 | Doull et al. (2018) [69] | Ql | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | Above average | Accept |

| Checklist | Gomez et al. (2014) [73] |

|---|---|

| Authority | |

| Associated with a reputable organisation? | Yes |

| Professional qualifications or considerable experience? | Yes |

| Produced/published other work (grey/black) in the field? | Yes |

| Recognised expert, identified in other sources? | Yes |

| Cited by others? | No |

| Higher degree student under “expert” supervision? | Not applicable |

| Is the organisation reputable? | Not applicable |

| Is the organisation an authority in the field? | Not applicable |

| Does the item have a detailed reference list or bibliography? | Not applicable |

| Score | 8 |

| Accuracy | |

| Does the item have a clearly stated aim or brief? | Yes |

| If so, is this met? | Yes |

| Does it have a stated methodology? | Yes |

| If so, is it adhered to? | Yes |

| Has it been peer-reviewed? | Yes |

| Has it been edited by a reputable authority? | Yes |

| Supported by authoritative, documented references or credible sources? | Not applicable |

| Is it representative of work in the field? | Yes |

| If no, is it a valid counterbalance? | Not applicable |

| Is any data collection explicit and appropriate for the research? | Yes |

| If item is secondary material, refer to the original. Is it an accurate, unbiased interpretation or analysis? | Not applicable |

| If original, is it an accurate, unbiased interpretation or analysis? | Not stated |

| Score | 11 |

| Coverage | |

| Are any limits clearly stated? | Not applicable |

| Score | 1 |

| Objectivity | |

| Opinion, expert or otherwise, is still opinion: is the author’s standpoint clear? | Yes |

| Does the work seem to be balanced in presentation? | Yes |

| Score | 2 |

| Date | |

| Does the item have a clearly stated date related to content? | Yes |

| If no date is given but can be closely ascertained, is there a valid reason for its absence? | Not applicable |

| Check the bibliography: has key contemporary material been included? | Not applicable |

| Score | 3 |

| Significance | |

| Is the item meaningful? (This incorporates feasibility, utility and relevance) | Yes |

| Does it add context? | Yes |

| Does it enrich or add something unique to the research? | Yes |

| Does it strengthen or refute a current position? | Yes |

| Would the research area be lesser without it? | Yes |

| Is it integral, representative, typical? | Yes |

| Does it have impact? | Yes |

| Score | 7 |

| AACODS score Grade Status | 32 Good Accept |

| No. | Author(s) (Year) | Quantitative Study Design | Country; Settings | Sample | Participants’ Characteristics | Relevant Barriers Identified (or Investigated) | Key Findings (on Dental Dams/Cling Film) | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yap et al., 2007 [87] | Cross-sectional descriptive design | Australia; Prisons in New South Wales | Two samples (1996 survey = 538 participants; 2001 survey = 747 participants) | Males and female inmates; no information on age and other sociodemographic characteristics was provided | Dental dam | (1) 54% of female inmates favoured (in their opinion) the use of dental dams in prisons. (2) 1% of female inmates opined that dental dam use would increase the rate of sexual assault among inmates | Inability of the authors to determine the proportion of use, by purpose, of the condoms and dental dams issued monthly in the surveyed prisons |

| 2 | Richters et al., (2010) [29] | Cross-sectional analytic design | Australia; community- and health facility-based | 543 participants | Women only, aged 16 to 64 years (median = 33 years); 65% were lesbians, dyke, homosexual or gay | Dental dam | (1) 86.7% of the participants had never used dental dams for oral sex. (2) The frequency of dental dam use was not significantly higher among women with multiple sexual partners, compared to those with one partner (RR = 1.5, CI = 0.7–3.0, p = 0.3). (3) Compared to those who had not engaged in group sex, women who had engaged in group sex were not more likely to use dental dams (RR = 1.64, CI = 0.6–4.5, p = 0.33). (4) Women who had had oral sex involving blood were significantly more likely to use dental dams (CI = 1.5–5.9, p = 0.002) | Not provided in the literature |

| 3 | Gil-Llario et al., (2022) [72] | Cross-sectional analytic design | Spain; different parts of Spain (community-based) | 327 participants | Only women who had sex with women (WSW); aged 18 to 60 years; mean age (SD) was 27.82 (9.35) years; 27.5% resided in central-eastern area | Dental dam | (1) 79.9% and 81% of the participants had never used dental dams for cunnilingus and anilingus, respectively. (2) Having older age, having high self-efficacy for dental dam use, being assertive, non-use of cannabis during sex, self-perception of HIV as a serious infection, and self-perception of one’s vulnerability to HIV infection were significant predictors of dental dam use in oral sex (p-values < 0.05) | Online recruitment of participants through LGBT organisations in Spain |

| 4 | Carlin et al. (1997) [66] | Cross-sectional analytic design | United Kingdom; health facility-based | 390 participants | HIV seropositive men; no information on age and other sociodemographic characteristics was provided | Dental dam | 150 participants were practising anilingus, of which only one (0.6%) had ever used a dental dam during sex | Not provided in the literature |

| 5 | Bailey et al. (2003) [92] | Cross-sectional analytic design | London, United Kingdom; community- and health facility-based | 1218 participants (Health facility = 803 participants; community = 415) | All were women Clinic Sample: Mean (SD) age was 31.2 (6.4) years; 92% Lesbian; 65% employed; 91% residing in London Community Sample: Mean (SD) age was 34.4 (9.8) years; 86% Lesbian; 64% employed; 68% residing in Other England and Scotland | Dental dam | 86% of those participants (n = 296) who indicated having had sex with women had never used dental dams | Not provided in the literature |

| 6 | Fujii (2019) [93] | Cross-sectional analytic design | Japan; events involving/engaging lesbian women (community-based) | 104 participants | 99% were registered females (1% were registered males); aged 19 to 55 years; mean (SD) age was 31 (8.9) years | Latex film (dental dam) | (1) 92.4% of the participants had never used latex film during oral sex. (2) A higher proportion of bisexuals (25.8%) had used latex film in oral sex compared to homosexuals (10.7%), although not statistically significant (p-value = 0.099). | (1) Study sample was not normally distributed. (2) The reliability and validity of the study instrument (questionnaire) were not tested. (3) Participants’ recruitment was at events where alcoholic beverages were served; the sample might be biased towards alcohol drinkers. (4) Possibility of biased responses due to the prevailing socio-cultural influence on homosexuality in Japan as at the time of data collection |

| 7 | Yap et al., (2010) [88] | Mixed methods study (Quantitative part: cross-sectional descriptive design) | Australia; Prisons in New South Wales | 199 participants (quantitative Part) | All were female inmates; 63% were heterosexual | Dental dam | Only 4% of the participants had ever used dental dam for oral sex (in prison) | Not provided in the literature |

| 8 | Zappulla et al. (2020) [90] | Cross-sectional analytic design | Melbourne, Australia; Health facility-based | 180 participants | All were female sexual workers; median age was 28 years; 86.7% spoke English at home | Dental dam | (1) Only 3.1% of those participants who had given cunnilingus used dental dams consistently. (2) A higher proportion (5.9%) of Asian-language speaking participants who had practiced cunnilingus used dental dams consistently, compared to their English-speaking counterparts (2.7%). This difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.428). (3) A higher proportion (5.3%) of those participants, who had practiced cunnilingus working in brothels used dental dams consistently, compared to their counterparts who worked privately or as escorts (0.0%). This difference was statistically significant (p-value = 0.585). | (1) The study was health facility-based; hence, it may not be representative of the general population. (2) It was difficult to ascertain the total number of female sexual workers invited to participate in the study (3) The proportion of Asian-language speaking participants was low; hence, the comparisons between the English speaking and the Asian-language speaking participants. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanmodi, K.K.; Egbedina, E.A.; Nkhata, M.J.; Nnyanzi, L.A. Experiences with Cling Film and Dental Dam Use in Oral Sex: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Oral 2023, 3, 215-246. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3020019

Kanmodi KK, Egbedina EA, Nkhata MJ, Nnyanzi LA. Experiences with Cling Film and Dental Dam Use in Oral Sex: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Oral. 2023; 3(2):215-246. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanmodi, Kehinde Kazeem, Eyinade Adeduntan Egbedina, Misheck Julian Nkhata, and Lawrence Achilles Nnyanzi. 2023. "Experiences with Cling Film and Dental Dam Use in Oral Sex: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review" Oral 3, no. 2: 215-246. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3020019

APA StyleKanmodi, K. K., Egbedina, E. A., Nkhata, M. J., & Nnyanzi, L. A. (2023). Experiences with Cling Film and Dental Dam Use in Oral Sex: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Oral, 3(2), 215-246. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3020019