Expansion of Preventive Dental Service Coverage for Certain Medicaid Beneficiaries in Texas: A Call for Dental Policy Effectiveness Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify factors associated with poor oral health: problem analysis.

- To determine the role of Medicaid expansion for preventive dental service coverage: solution analysis.

- To identify critics of public insurance policies such as Medicaid expansion of preventive dental services and describe their role in influencing the process of transitioning from bill to policy.

- To propose an evidence-based theory framework and research methodology for future research.

- To identify key outcome variables, independent variables, covariates, identification strategy for causal analysis of policy effectiveness, and potential validity threats.

2. Problem Analysis: Oral Health and Preventive Dental Services

3. Solution Analysis: Public Dental Insurance Coverage and Access to Dental Care

3.1. Critics of Legislation-Public Insurance Policies

3.2. Measuring Policy Effects-Empirical Literature

3.3. Research Methods Proposal-Studying the Effects of the Filed Senate Bill 87(R) 1152 in Texas-Research Approach to Provide Evidence-Based Effect for the Bill Vote

3.4. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The Concept of Access. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

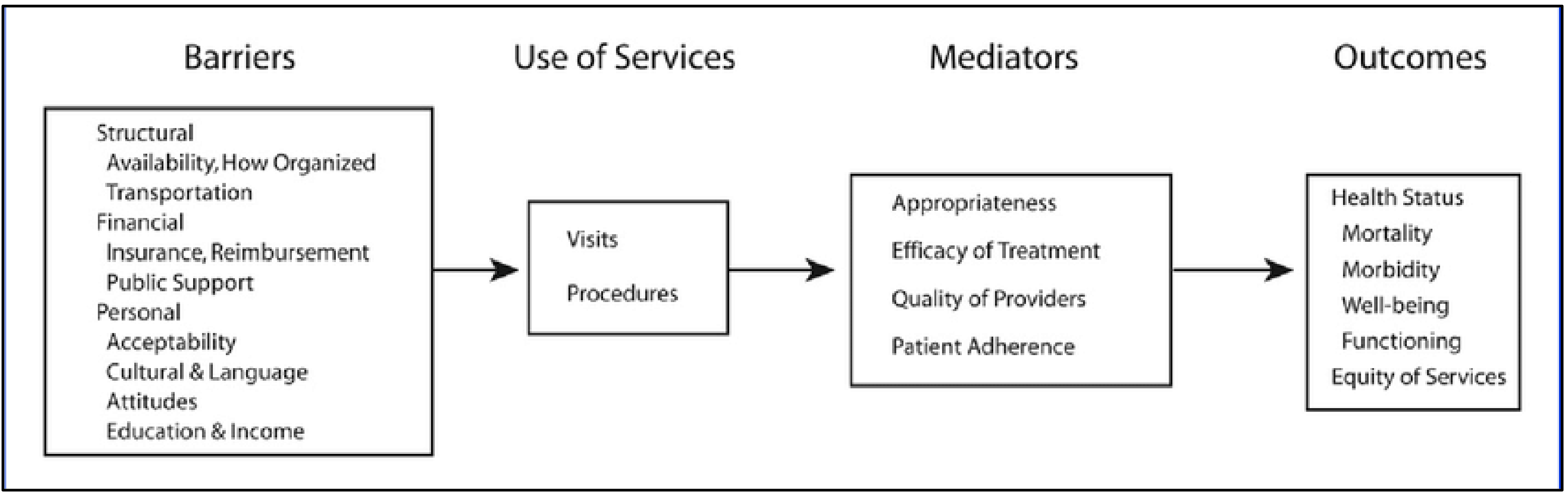

- Academies. Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services I of M. A model for monitoring access. In Access to Health Care in America; Academies: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Raising the Excise Tax on Cigarettes: Effects on Health and the Federal Budget; Executive Summary; Congressional Budget Office: Washington, DC, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjewski, T.P.; Zhang, F.; Eliott, D.; Wharam, J.F. Effect of Massachusetts Health Reform on Chronic Disease Outcomes. Health. Serv. Res. 2014, 49 (Suppl. S2), 2086–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, W.G.; Newhouse, J.P.; Duan, N.; Keeler, E.B.; Leibowitz, A.; Marquis, M.S. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1987, 77, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mcginn-Shapiro, M. Medicaid Coverage of Adult Dental Services; The National Academy for State Health Policy: Washington, DC, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

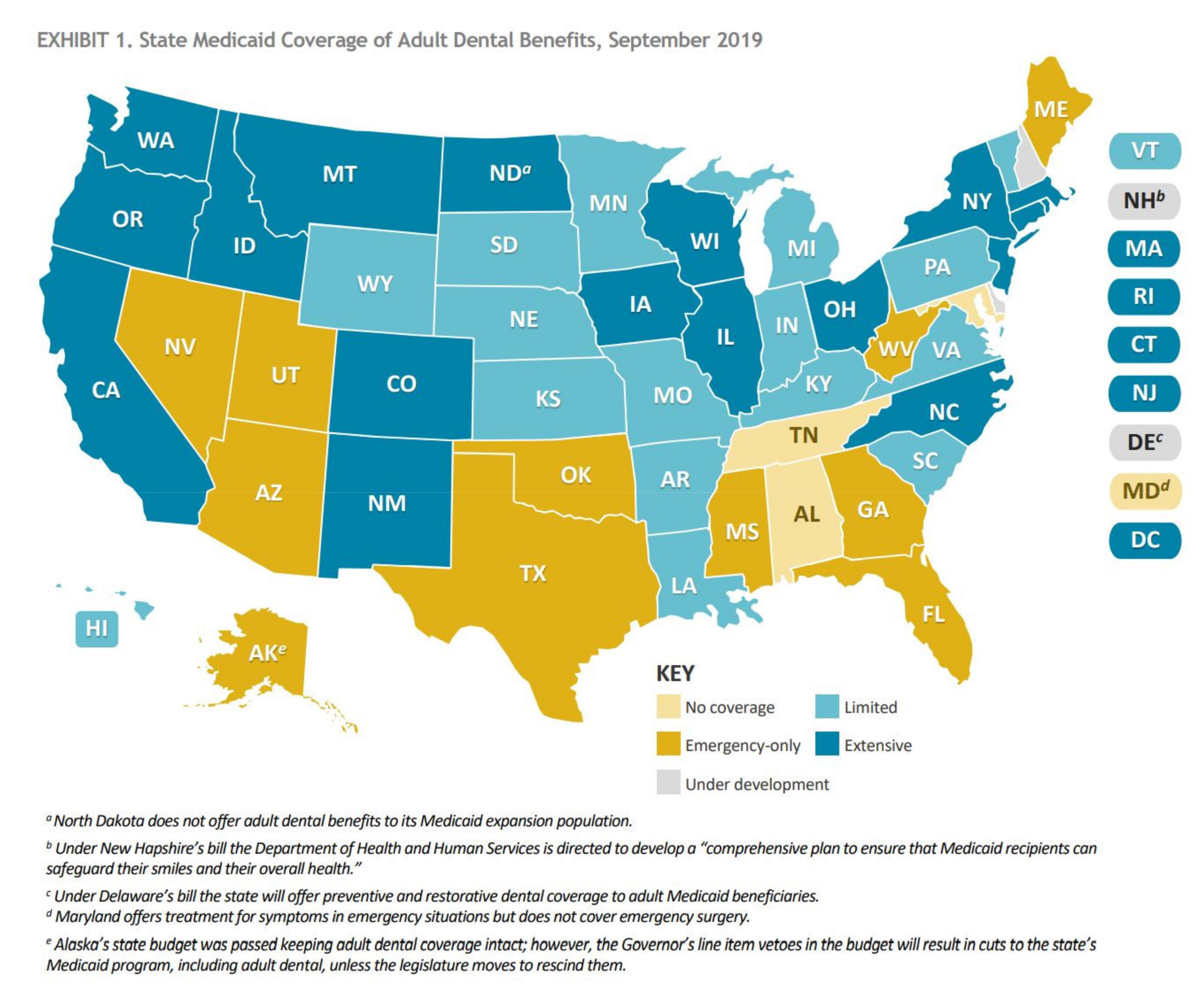

- Medicaid Adult Dental Benefits: An Overview. 2019. Available online: https://www.chcs.org/resource/medicaid-adult-dental-benefits-overview/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- DentaQuest. Reversible Decay: Oral Health Is A Public Health Problem We Can Solve. 2019. Available online: https://dentaquest.com/pdfs/reports/reversible-decay.pdf/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Antonisse, L.; Garfield, R.; Rudowitz, R.; Artiga, S. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review; Kaiser Family Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Sommers, B.D.; Grabowski, D.C. What Is Medicaid? More Than Meets the Eye. JAMA 2017, 318, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, B.D.; Gawande, A.A.; Baicker, K. Health Insurance Coverage and Health—What the Recent Evidence Tells Us. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, L.; Paradise, J.; Thompson, V. Data Note: Medicaid’s Role in Providing Access to Preventive Care for Adults; Kaiser Family Foundation: Washington, DC, WA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-medicaids-role-in-providing-access-to-preventive-care-for-adults/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Huang, S.S. Should Medicaid include adult coverage for preventive dental procedures? What evidence is needed? J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazin, S.; Guerra, V.; McMohan, S. Strategies C for H.C. Strategies to Improve Dental Benefits for the Medicaid Expansion Population; Center for Healthcare Strategies Inc.: Hamilton, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.chcs.org/resource/strategies-to-improve-dental-benefits-for-the-medicaid-expansion-population/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Remler, D.K.; Greene, J. Cost-Sharing: A Blunt Instrument. Annu. Rev. Public Heal. 2009, 30, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.; Price, M.; Vogeli, C.; Brand, R.; Chernew, M.E.; Chaguturu, S.K.; Weil, E.; Ferris, T.G. Bending the Spending Curve By Altering Care Delivery Patterns: The Role Of Care Management Within A Pioneer ACO. Heal. Aff. 2017, 36, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikes, D.; Zutshi, A.; Genevro, J.L.; Parchman, M.L.; Meyers, D.S. Early evaluations of the medical home: Building on a promising start. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Whittington, J.W.; Nolan, K.; Lewis, N.; Torres, T. Pursuing the Triple Aim: The First 7 Years. Milbank Q. 2015, 93, 263–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, S. Medicaid Is Worse Than No Coverage at All. Wall Str. J 2011. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704758904576188280858303612 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Miller, D. Growing Medicaid Budgets Squeezing Out Other Priorities; CSG: Lexington, KY, USA, 2012; Available online: http://knowledgecenter.csg.org/kc/content/growing-medicaid-budgets-squeezing-out-other-priorities (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Newhouse, J.P. Assessing Health Reform’s Impact on Four Key Groups of Americans. Heal. Aff. 2010, 29, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sommers, B.D.; Epstein, A.M. U.S. Governors and the Medicaid Expansion—No Quick Resolution in Sight. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommers, B.D.; Gruber, J. Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets From Increased Spending Related To Medicaid Expansion. Heal. Aff. 2017, 36, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, B. Medicaid Dental System an Ongoing Challenge; The Texas Tribune: Austin, TX, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2012/07/27/medicaid-dental-disaster-leaves-children-lurch/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Avendano, E. Lawmakers Look to Add Dental Coverage for Medicaid Recipients; Honolulu Civil Beat: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/02/lawmakers-look-to-add-dental-coverage-for-medicaid-recipients/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Aday, L.; Begley, C.; Lairson, D.; Slater, C. Evaluating the Healthcare System: Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Equity. Third. Academy Health. 2004. Available online: http://www.getcited.org/pub/100326183 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Mazurenko, O.; Balio, C.P.; Agarwal, R.; Carroll, A.E.; Menachemi, N. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: A Systematic Review. Heal. Aff. 2018, 37, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtemanche, C.; Marton, J.; Ukert, B.; Yelowitz, A.; Zapata, D. Early Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage in Medicaid Expansion and Non-Expansion States. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2016, 36, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmueller, T.; Levinson, Z.M.; Levy, H.G.; Wolfe, B. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage. Am. J. Public Heal. 2016, 106, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golberstein, E.; Gonzales, G.; Sommers, B.D. California’s Early ACA Expansion Increased Coverage and Reduced out-of-Pocket Spending For The State’s Low-Income Population. Heal. Aff. 2015, 34, 1688–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow, S.; Long, S.K.; Kenney, G.M.; Anderson, N. Uninsurance Disparities Have Narrowed For Black And Hispanic Adults Under The Affordable Care Act. Heal. Aff. 2015, 34, 1774–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H.A.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Chino, J. Insurance coverage among women diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, B.D.; Chua, K.-P.; Kenney, G.M.; Long, S.K.; McMorrow, S. California’s Early Coverage Expansion under the Affordable Care Act: A County-Level Analysis. Heal. Serv. Res. 2015, 51, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angier, H.; Hoopes, M.; Gold, R.; Bailey, S.R.; Cottrell, E.K.; Heintzman, J.; Marino, M.; DeVoe, J.E. An Early Look at Rates of Uninsured Safety Net Clinic Visits after the Affordable Care Act. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoli, G.J. Effects of Expanded California Health Coverage on Hospitals: Implications for ACA Medicaid Expansions. Heal. Serv. Res. 2015, 51, 1368–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.A.; Fleishman, J.A.; Yehia, B.R.; Cheever, L.W.; Hauck, H.; Korthuis, P.T.; Mathews, W.C.; Keruly, J.; Nijhawan, A.E.; Agwu, A.L.; et al. Healthcare Coverage for HIV Provider Visits Before and After Implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breathett, K.; Allen, L.A.; Helmkamp, L.; Colborn, K.; Daugherty, S.L.; Khazanie, P.; Lindrooth, R.; Peterson, P.N. The Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Correlated with Increased Heart Transplant Listings in African-Americans But Not Hispanics or Caucasians. JACC Hear. Fail. 2017, 5, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.B.; Galarraga, O.; Wilson, I.B.; Wright, B.; Trivedi, A.N. At Federally Funded Health Centers, Medicaid Expansion Was Associated with Improved Quality of Care. Heal. Aff. 2017, 36, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresden, S.M.; Powell, E.S.; Kang, R.; McHugh, M.; Cooper, A.J.; Feinglass, J. Increased Emergency Department Use in Illinois after Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 69, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasseh, K.; Vujicic, M. The Impact of Medicaid Reform on Children’s Dental Care Utilization in Connecticut, Maryland, and Texas. Heal. Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmueller, T.; Orzol, S.; Shore-Sheppard, L.D. The Effect of Medicaid Payment Rates on Access to Dental Care among Children. Am. J. Heal. Econ. 2015, 1, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Griffin, S.; Barker, L.K.; Wei, L.; Li, C.-H.; Albuquerque, M.S.; Gooch, B.F. Use of dental care and effective preventive services in preventing tooth decay among U.S. Children and adolescents—Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, United States, 2003–2009 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005–2010. MMWR Suppl. 2014, 63, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 34–102. [Google Scholar]

| Stakeholders | Healthcare Physicians and Dentists | Taxpayers of Texas | Texas State Governor | Texas Beneficiaries of the Policy | Political Parties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Provide needed healthcare service [8] | Pay taxes as prescribed, which in return funds public programs | Educate the population, serve the healthcare needs of population, improve healthcare provision, support policies beneficial to state, authorize needed actions for state benefit | Seek and receive care [8] | Provide vote, lobby, or influence key players for passing a bill in the context of policy |

| Level of Interest | Moderate As depends on direction of reimbursement amounts | Moderate Depending on the movement of the bill | High As impacts state budget deficits and reallocation or resources | High Because they receive access to care | High [25] |

| Level of Influence | Moderate As depends on the level of policy development involvement allowed by legislatures and market concentration | Moderate No influence other than voting, campaigning against the bill | High | Moderate No influence other than voting or campaigning about rights to the extremes | High Help support or oppose the policy in legislation depending on the role |

| Perspective/Need | Provide quality/effective/evidence-based care in return of competitive timely reimbursement | Receive quality services funded by state government such as primary education, better transportation and other state community priorities | To serve the community for their wellbeing and safety | Overall wellbeing, continuity of care and improved productivity | Political perspective is satisfied or provide majority through voting benefiting their respective parties |

| Level of impact of policy on them | Moderate Only high in cases when increased amount of reimbursement | Low The bill does not impact them directly | High If bill passes, the state budget will be impacted [25] | High Better access to care | Moderate If the bill passes, no direct impact |

| Level of friction/opposition | Low Agree that access to preventive dental care improves overall health [8] | High As per past fraudulent incident among Medicaid Dental Beneficiaries, they might perceive the bill to be a facilitator of more frauds [24] | High As the favor towards passing the bill might have its own consequences. The fact that the existing administration since past years have not passed it for same underlying reasons | Low As need improved access to dental care services [8] | High By opposition party |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patel, N.; Patel, N. Expansion of Preventive Dental Service Coverage for Certain Medicaid Beneficiaries in Texas: A Call for Dental Policy Effectiveness Action. Oral 2021, 1, 261-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1030025

Patel N, Patel N. Expansion of Preventive Dental Service Coverage for Certain Medicaid Beneficiaries in Texas: A Call for Dental Policy Effectiveness Action. Oral. 2021; 1(3):261-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1030025

Chicago/Turabian StylePatel, Naiya, and Neel Patel. 2021. "Expansion of Preventive Dental Service Coverage for Certain Medicaid Beneficiaries in Texas: A Call for Dental Policy Effectiveness Action" Oral 1, no. 3: 261-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1030025

APA StylePatel, N., & Patel, N. (2021). Expansion of Preventive Dental Service Coverage for Certain Medicaid Beneficiaries in Texas: A Call for Dental Policy Effectiveness Action. Oral, 1(3), 261-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1030025