Hematological Inflammatory Markers and Chronic Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

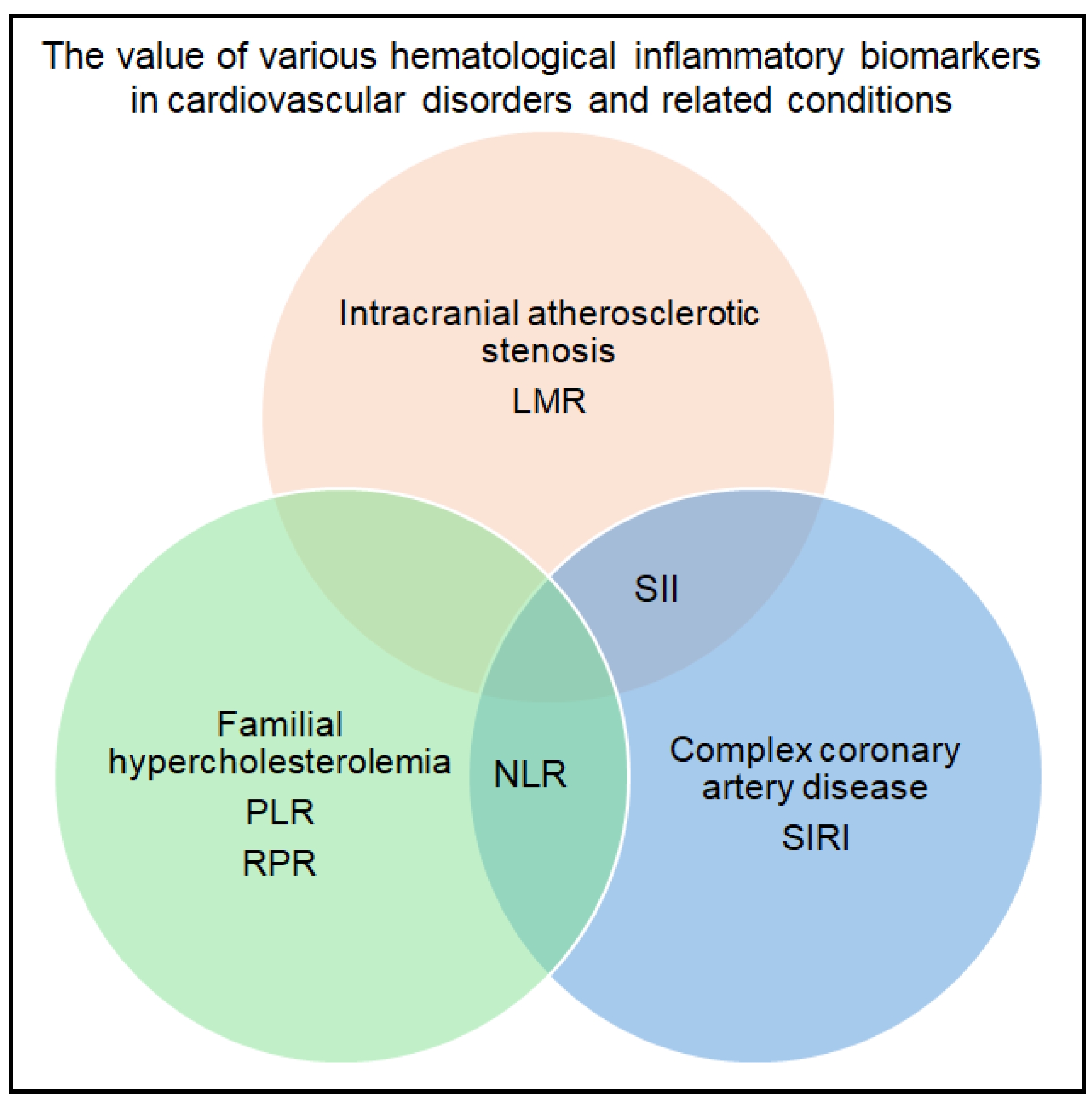

3.1. Cardiovascular Disorders and Associated Conditions

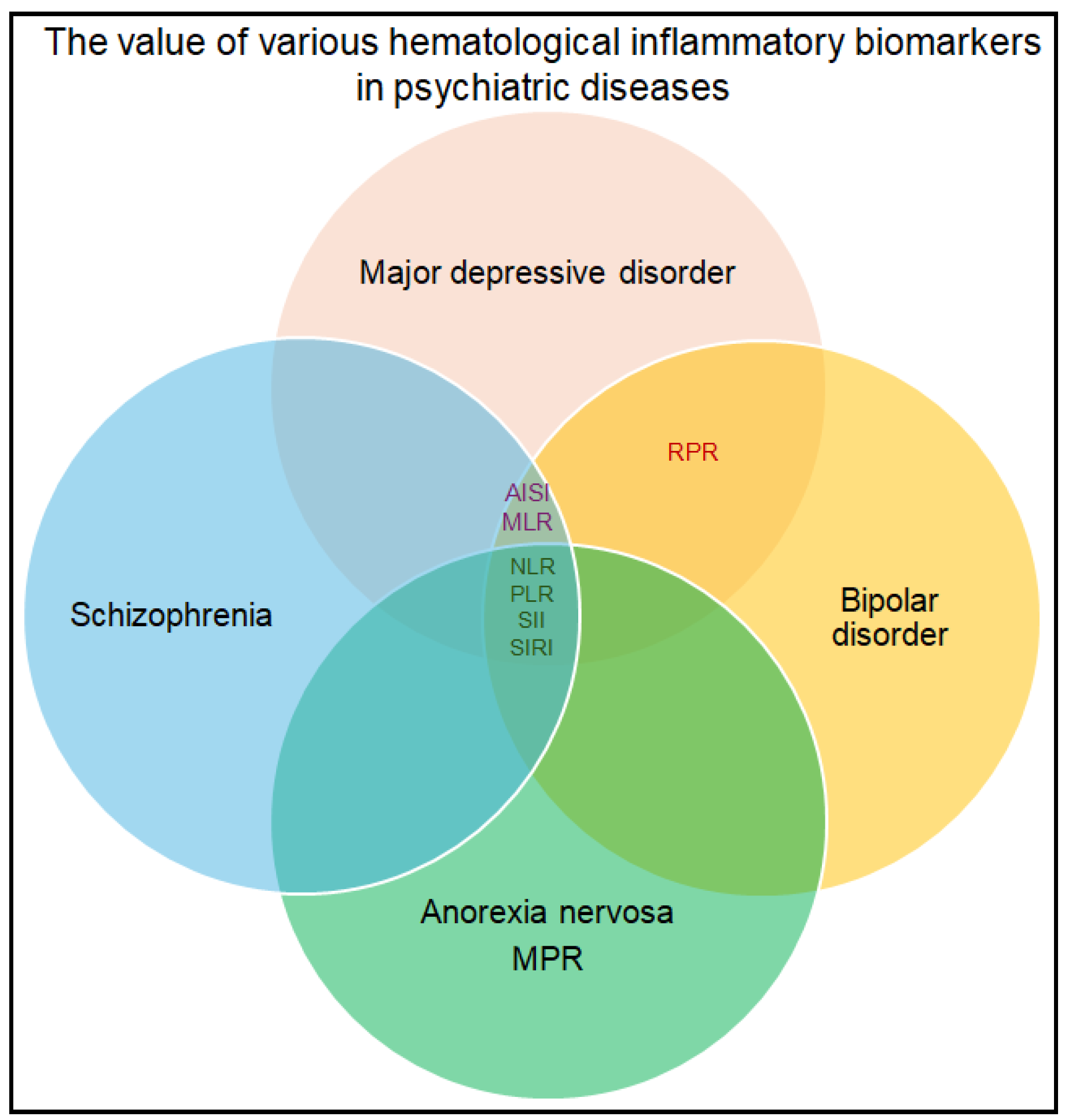

3.2. Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders

3.3. Chronic Infections

3.4. Dermatological Conditions

3.5. Diabetes Mellitus

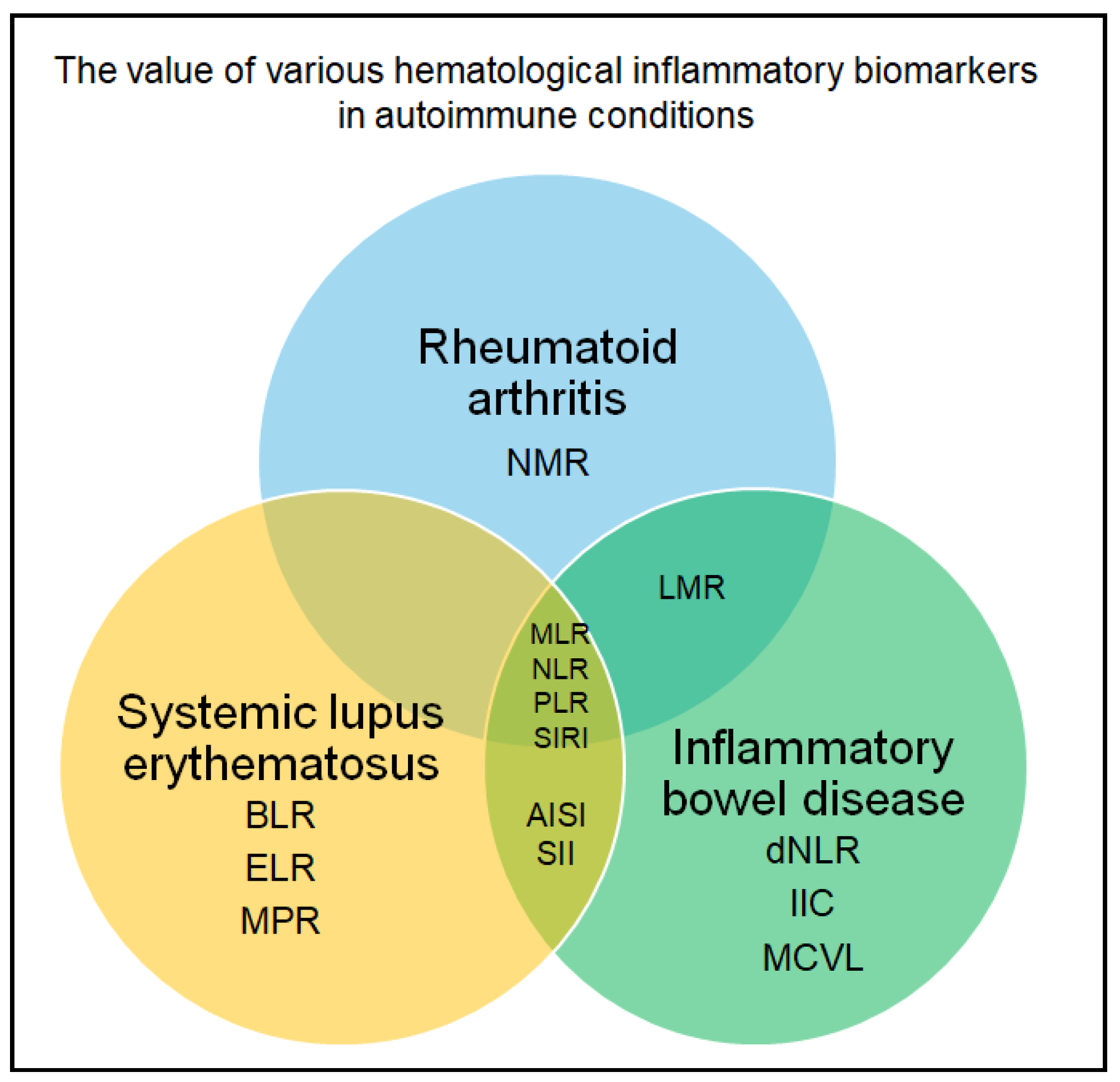

3.6. Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions

3.7. Other Chronic Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | alopecia areata |

| ADHD | attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| AISI | aggregate index of systemic inflammation |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| BD | bipolar disorder |

| BLR | basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| DAPSA | disease activity in psoriatic arthritis |

| DII | dietary inflammatory index |

| dNLR | derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| DVT | deep vein thrombosis |

| ELR | eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| IIC | cumulative inflammatory index |

| FH | familial hypercholesterolemia |

| LMR | lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio |

| LTBI | latent tuberculosis infection |

| MCVL | mean corpuscular volume - lymphocytes ratio |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| MLR | monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| MPR | monocyte-to-platelet ratio |

| NLR | neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| NMR | neutrophil-to-monocyte ratio |

| NPR | neutrophil-platelet ratio |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PIV | pan-immune-inflammation value |

| PLR | platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PMR | platelet-to-monocyte ratio |

| PNP | polyneuropathy |

| PRS | polygenic risk score |

| PWR | platelet-to-white blood cell ratio |

| RLR | red cell distribution width-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| RPR | red cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio |

| SCZ | schizophrenia |

| SII | systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SIRI | systemic inflammation response index |

References

- Hacker, K. The Burden of Chronic Disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 8, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterhoff, M.; van der Maas, M.E.; Steuten, L.M. A Systematic Review of Health Economic Evaluations of Diagnostic Biomarkers. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2016, 14, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, L.; Giglio, R.V.; Bivona, G.; Scazzone, C.; Gambino, C.M.; Iacona, A.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Lo Sasso, B.; Ciaccio, M. The Value of a Complete Blood Count (CBC) for Sepsis Diagnosis and Prognosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, V.; Dominiak, M. An underrated clinical tool: CBC-derived inflammation indices as a highly sensitive measure of systemic immune response and inflammation. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 34, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novellino, F.; Donato, A.; Malara, N.; Madrigal, J.L.; Donato, G. Complete blood cell count-derived ratios can be useful biomarkers for neurological diseases. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 20587384211048264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, A. The diagnostic role of the systemic inflammation index in patients with immunological diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Hu, T.; Wang, J.; Xiao, R.; Liao, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, Z. Systemic immune-inflammation index as a potential biomarker of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 933913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ke, J.; Qiu, F.; Fan, W.; Wei, S. Associations of complete blood cell count-derived inflammatory biomarkers with asthma and mortality in adults: A population-based study. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1205687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariean, C.R.; Tiuca, O.M.; Mariean, A.; Cotoi, O.S. Variation in CBC-Derived Inflammatory Biomarkers Across Histologic Subtypes of Lung Cancer: Can Histology Guide Clinical Management? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambichler, T.; Schuleit, N.; Susok, L.; Becker, J.C.; Scheel, C.H.; Torres-Reyes, C.; Overheu, O.; Reinacher-Schick, A.; Schmidt, W. Prognostic Performance of Inflammatory Biomarkers Based on Complete Blood Counts in COVID-19 Patients. Viruses 2023, 15, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawati, W.; Machin, A.; Aryati, A. The Role of Complete Blood Count-Derived Inflammatory Biomarkers as Predictors of Infection After Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, D.; Cui, J.; Sha, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tang, N.; Wang, N.; Huang, A.; Xia, J. Diagnostic accuracy of red blood cell distribution width to platelet ratio for predicting staging liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e15096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, D.-G.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Jung, J.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Suk, K.-T.; Jang, M.-K.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Kim, D.-J.; et al. Platelet-to-White Blood Cell Ratio: A Feasible Biomarker for Pyogenic Liver Abscess. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Hu, S. Association between red cell distribution width-to-lymphocyte ratio and 30-day mortality in patients with ischemic stroke: A retrospective cohort study. Thromb. J. 2024, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, R.-E.; Popescu, D.-M.; Boldeanu, M.-V.; Florescu, D.N.; Șerbănescu, M.-S.; Șandru, V.; Panaitescu-Damian, A.; Forțofoiu, D.; Șerban, R.-C.; Gherghina, F.-L.; et al. The Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Inflammatory Markers, Including the New Cumulative Inflammatory Index (IIC) and Mean Corpuscular Volume/Lymphocyte (MCVL), in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.B.; Huang, L.X.; Huang, Z.R.; Lu, L.M.; Luo, B.; Cai, W.Q.; Liu, A.M.; Wang, S.W. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis plaque instability. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 915126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaseghi, G.; Heshmat-Ghahdarijani, K.; Taheri, M.; Ghasempoor, G.; Hajian, S.; Haghjooy-Javanmard, S.; Aliyari, R.; Shafiee, Z.; Shekarchizadeh, M.; Pourmoghadas, A.; et al. Hematological Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Clinically Confirmed Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5051434, Erratum in Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 9851784. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9851784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Michalak, M.; Komosa, A.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Filipiak, K.J.; Tykarski, A.; Jemielity, M. Predictive value of systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) for complex coronary artery disease occurrence in patients presenting with angina equivalent symptoms. Cardiol. J. 2024, 31, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamrani, F.; Imannezhad, M.; Kachouei, A.A.; Sobhani, S.R.; Khorasanchi, Z. Dietary inflammatory index and its association with hematological inflammatory markers: A cross-sectional analysis in healthy and depressed individuals. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhun, H.A.; Gürbüzer, N. New Hematological Parameters as Inflammatory Biomarkers: Systemic Immune Inflammation Index, Platerethritis, and Platelet Distribution Width in Patients with Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2022, 6, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, M.D.E.; Jiménez-Sánchez, L.; Shen, X.; Edmondson-Stait, A.J.; Green, C.; Adams, M.J.; Rifai, O.M.; McIntosh, A.M.; Lyall, D.M.; Whalley, H.C.; et al. Associations between major psychiatric disorder polygenic risk scores and blood-based markers in UK biobank. Brain Behav Immun. 2021, 97, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, D.; Xu, H.; Yin, L.; Chen, J. Characteristics of platelet-associated parameters and their predictive values in Chinese patients with affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qiu, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Lei, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, S. Retrospective evaluation of novel serum inflammatory biomarkers in first-episode psychiatric disorders: Diagnostic potential and immune dysregulation. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1442954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rog, J.; Karakuła, K.; Rząd, Z.; Niedziałek-Serafin, K.; Juchnowicz, D.; Rymuszka, A.; Karakula-Juchnowicz, H. The Prognostic Value of Hematological, Immune-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Hormonal Biomarkers in the Treatment Response of Hospitalized Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ninla-Aesong, P.; Kietdumrongwong, P.; Neupane, S.P.; Puangsri, P.; Jongkrijak, H.; Chotipong, P.; Kaewpijit, P. Relative value of novel systemic immune-inflammatory indices and classical hematological parameters in predicting depression, suicide attempts and treatment response. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.H.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, J.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, J.H. Predictive Values of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, and Other Prognostic Factors in Pediatric Patients with Bell’s Palsy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Xu, X.H.; Ren, L.N.; Xu, X.F.; Dai, Y.L.; Yang, R.R.; Jin, C.Q. The diagnostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, albumin to fibrinogen ratio, and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in Parkinson’s disease: A retrospective study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1450221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stanca, I.D.; Criciotoiu, O.; Neamtu, S.D.; Vasile, R.C.; Berceanu-Bora, N.M.; Minca, T.N.; Pirici, I.; Rosu, G.C.; Bondari, S. The Analysis of Blood Inflammation Markers as Prognostic Factors in Parkinson’s Disease. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dezayee, Z. Relationship Between T-helper 1 Inflammatory Biomarkers and Hematological Index Responses in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Cureus 2024, 16, e75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; He, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, W.; Sun, S.; Li, Z.; Shi, J. Association between hematological inflammatory markers and latent TB infection: Insights from NHANES 2011–2012 and transcriptomic data. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1556048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, X.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, H.; Wu, W. Inflammatory Markers as Predictors of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Analysis of Hematological Parameters and Clinical Features. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2025, 18, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, T.S.; Hummerstone, C.Y.; Billahalli, T.; Ward, R.J.B.; Barnes, K.E.; Marshall, N.J.; Spong, V.C.; Bothamley, G.H. The monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio: Sex-specific differences in the tuberculosis disease spectrum, diagnostic indices and defining normal ranges. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sağlam, N.Ö.; Civan, H.A. Impact of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection on inflammatory markers and hematological parameters. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qiu, Y.; He, X.; Mao, W.; Han, Z. Platelet-to-white blood cell ratio: A novel and promising prognostic marker for HBV-associated decompensated cirrhosis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, J.; Mao, W. Evaluation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, and red cell distribution width for the prediction of prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilir, F.; Chkhikvadze, M.; Yilmaz, A.Y.; Kose, O.; Arıöz, D.T. Prognostic value of systemic inflammation response index in patients with persistent human papilloma virus infection. Ginekol. Pol. 2022, 93, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, H.S.; Srivastava, R.; Gummaluri, S.S.; Agarwal, M.C.; Bhattacharya, P.; Astekar, M.S. Comparison of blood parameters between periodontitis patients and healthy participants: A cross-sectional hematological study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022, 26, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy Sarac, G.; Acar, O.; Nayır, T.; Hararcı Yıldırım, P.; Dinçer Rota, D. The Use of New Hematological Markers in the Diagnosis of Alopecia Areata. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2023, 13, e2023118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A.; Demirbas, G.U.; Diremsizoglu, E.; Islamoglu, G. Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Isotretinoin: Evaluation of Red Cell Distribution Width to Lymphocyte and Platelet Ratios as New Hematological Markers and Clinical Outcomes in Acne Vulgaris. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, E.; Bayraktar, M. Relationships Between Disease Severity and the C-reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio and Various Hematological Parameters in Patients with Acne Vulgaris. Cureus 2023, 15, e44089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, A.; Aghayani, S.; Najafizadeh, S.R.; Saffarian, Z.; Yaseri, M. Exploring the Association between Blood Indices and Skin and Joint Activity of Psoriatic Arthritis. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 23, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, A.S.; Al Shambaky, A.Y.; Ameen, S.G.; Sobih, A.K. Hematological indices in psoriatic enthesopathy: Relation to clinical and ultrasound evaluation. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 43, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyan, O.; Dumur, S.; Elgormus, N.; Uzun, H. The Relationship between Vitamin D, Inflammatory Markers, and Insulin Resistance in Children. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, M.; Song, Y. The relationship between peripheral blood inflammatory markers and diabetic macular edema in patients with severe diabetic retinopathy. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taban, N.; Bhat, M.H.; Sayeed, S.I.; Majid, S.; Lone, S.; Muzaffar, M.; Hakak, A.; Nyiem, M.; Bashir, H. Comparative Evaluation of Inflammatory Markers NLR, PLR, IL-6, and HbA1c in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Hospital Based Study. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran. 2025, 39, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chollangi, S.; Rout, N.K.; Satpathy, S.K.; Panda, B.; Patro, S. Exploring the Correlates of Hematological Parameters with Early Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cureus 2023, 15, e39778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, L.; Kalejaiye, O.O.; Olopade, O.B.; Kehinde, M. Relationship Between Hematologic Inflammatory Markers and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria. Cureus 2024, 16, e68186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, V.; Mohanty, S.; Das, D.; Ghosh, A.; Maiti, R.; Nanda, P. Hematological Parameters as an Early Marker of Deep Vein Thrombosis in Diabetes Mellitus: An Observational Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e36813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uslu, M.F.; Yılmaz, M. Are Inflammatory Markers Important for Assessing the Severity of Diabetic Polyneuropathy? Medicina 2025, 61, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlShareef, A.A.; Alrawaili, M.S.; Almutairi, S.A.; Ayyad, M.M.; Alshora, W. Association of Hematological Parameters and Diabetic Neuropathy: A Retrospective Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalu, A.M.; Serban, D.; Tanasescu, D.; Vancea, G.; Cristea, B.M.; Stana, D.; Nicolae, V.A.; Serboiu, C.; Tribus, L.C.; Tudor, C.; et al. The Value of White Cell Inflammatory Biomarkers as Potential Predictors for Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aygün, K.; Asma Sakalli, A.; Küçükerdem, H.S.; Aygün, O.; Gökdemir, Ö. Assessment of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume values in patients with diabetes mellitus diagnosis: A case-control study. Medicine 2024, 103, e39661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, S.; Choudhary, A.; Sharma, V.; Mahajan, A.; Sahoo, D.; Pattnaik, S.S. Evaluating Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index as Distinctive Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with and Without Proteinuria: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e79348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domerecka, W.; Kowalska-Kępczyńska, A.; Homa-Mlak, I.; Michalak, A.; Mlak, R.; Mazurek, M.; Cichoż-Lach, H.; Małecka-Massalska, T. Usefulness of Extended Inflammation Parameters and Systemic Inflammatory Response Markers in the Diagnostics of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Cells 2022, 11, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Sierra, M.; Quevedo-Rodríguez, A.; Romo-Cordero, A.; González-Chretien, G.; Quevedo-Abeledo, J.C.; de Vera-González, A.; González-Delgado, A.; Martín-González, C.; González-Gay, M.Á.; Ferraz-Amaro, I. Relationship of Blood Inflammatory Composite Markers with Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Life 2023, 13, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masoumi, M.; Bozorgi, M.; Nourmohammadi, Z.; Mousavi, M.J.; Shariati, A.; Karami, J. Evaluation of hematological markers as prognostic tools in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2024, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targońska-Stępniak, B.; Grzechnik, K.; Kolarz, K.; Gągoł, D.; Majdan, M. Systemic Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Elderly-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (EORA) and Young-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis (YORA)-An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, J.M.A.S.; Almjydy, M.M.A.; Garban, M.A.Q.; Al-Hebari, F.S.Q.; Al-Washah, N.A.H. Neutrophil-to-monocyte ratio is the better new inflammatory marker associated with rheumatoid arthritis activity. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.H.; Cai, W.X.; Xiang, X.H.; Zhou, M.Y.; Sun, X.; Ye, H.; Li, R. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as a haematological marker of synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis with normal acute phase reactant level. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2346546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Targońska-Stępniak, B.; Zwolak, R.; Piotrowski, M.; Grzechnik, K.; Majdan, M. The Relationship between Hematological Markers of Systemic Inflammation (Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte, Platelet-To-Lymphocyte, Lymphocyte-To-Monocyte Ratios) and Ultrasound Disease Activity Parameters in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Bag, O.; Makay, B.; Omur Ecevit, C. Papel de los parámetros hematológicos en el diagnóstico de Artritis Idiopatica Juvenil en niños con artritis [Role of Hematological Parameters in the Diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis in Children with Arthritis]. Andes Pediatr. 2022, 93, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Kumar, A.; Mittal, A.; Singh, R.; Chaudhary, N. Diagnostic Utility of the Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and Absolute Lymphocyte Count in Distinguishing Thyroiditis vs Other Benign Causes of Thyroid Enlargement. Cureus 2025, 17, e81379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocak, T.; Lermı, N.; Yılmaz Bozkurt, Z.; Yagız, B.; Coskun, B.N.; Dalkılıc, E.; Pehlıvan, Y. Pan-immune-inflammation value could be a new marker to differentiate between vascular Behçet’s disease and non-vascular Behçet’s disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 28, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kıvrakoğlu, F.; Ergin, M.; Koşar, K. Evaluation of the systemic immune-inflammation index in relation to histological stages of celiac disease. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, G.Ö.; Vazgeçer, E.O.; Sözeri, B. Assessment of hematologic indices for diagnosis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatologia 2024, 62, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suszek, D.; Górak, A.; Majdan, M. Differential approach to peripheral blood cell ratios in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and various manifestations. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Torres, V.; Castejón, R.; Mellor-Pita, S.; Tutor-Ureta, P.; Durán-Del Campo, P.; Martínez-Urbistondo, M.; Vázquez-Comendador, J.; Gutierrez-Rojas, Á.; Rosado, S.; Vargas-Nuñez, J.A. Usefulness of the hemogram as a measure of clinical and serological activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2022, 5, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, X.; Huo, K.; Gao, H.; Ge, H. The clinical value of lymphocyte percentages and the monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio in differentiating immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy from dermatomyositis. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1581206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, N.; Ibrahim, S.; Ramadhan, A.A. Diagnostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clinical and Endoscopic Correlations. Cureus 2025, 17, e84073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Shen, C.; Zhong, Y.; Ooi, J.D.; Eggenhuizen, P.J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, T.; Meng, T.; Xiao, Z.; et al. High levels of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio may predict reduced risk of end stage of renal disease in Chinese patients with MPO-ANCA associated vasculitis. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2022, 47, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poenariu, I.S.; Boldeanu, L.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Caragea, D.C.; Cristea, O.M.; Pădureanu, V.; Siloși, I.; Ungureanu, A.M.; Statie, R.C.; Ciobanu, A.E.; et al. Interrelation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Alpha (HIF-1 α) and the Ratio between the Mean Corpuscular Volume/Lymphocytes (MCVL) and the Cumulative Inflammatory Index (IIC) in Ulcerative Colitis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, H.; Li, J. Common laboratory blood test immune panel markers are useful for grading ulcerative colitis endoscopic severity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pană, N.; Ștefan, G.; Popa, T.; Ciurea, O.; Stancu, S.H.; Căpușă, C. Prognostic Value of Inflammation Scores and Hematological Indices in IgA and Membranous Nephropathies: An Exploratory Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekir, S.A.; Yalcinsoy, M.; Gungor, S.; Tuncay, E.; Akyil, F.T.; Sucu, P.; Yavuz, D.; Boga, S. Prognostic value of inflammatory markers determined during diagnosis in patients with sarcoidosis: Chronic versus remission. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2021, 67, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.K.; Altin, R.; Sari, A. Can We Determine Osteoarthritis Severity Based on Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyif, B.; Yavuzcan, A.; Yurtçu, E.; Başbuğ, A.; Düzenli, F.; Keyif, E.; Goynumer, F.G. Exploring the Inflammatory Basis of Endometrial Polyps: Clinical Implications of Hematological Biomarkers in a Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nouri, B.; Talebian, N.; Kharaz, L.; Falah Tafti, M. Diagnostic Value of Serum Cancer Antigen 125, Carcinoembryonic Antigen, Cancer Antigen 19-9, Anti Müllerian Hormone, White Blood Cell Count, Platelet Count, and Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in Endometriosis: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2025, 19, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pau, M.C.; Zinellu, A.; Mangoni, A.A.; Paliogiannis, P.; Lacana, M.R.; Fois, S.S.; Mellino, S.; Fois, A.G.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, E.; et al. Evaluation of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Markers in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.; Xiao, J.; Cai, W.; Lu, X.; Liu, C.; Dong, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Song, G.; Sun, Q.; Wang, H.; et al. Association of the systemic immune-inflammation index with anemia: A population-based study. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1391573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Atik, I.; Atik, S. Relationship between sacroiliitis and inflammatory markers in familial Mediterranean fever. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2024, 70, e20240068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciceri, A.C.M.; de Oliveira, L.E.; Richter, A.L.; de Carvalho, J.A.M.; Lucena, M.R.; Gomes, G.W.; Figueiredo, M.S.; Nunes Dos Santos, M.N.; Blaia-D’Avila, V.L.N.; Cançado, R.D.; et al. Hematological ratios and cytokine profiles in heterozygous beta-thalassemia. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2025, 47, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Najafzadeh, M.J.; Baniasad, A.; Shahabinejad, R.; Mashrooteh, M.; Najafipour, H.; Gozashti, M.H. Investigating the relationship between haematological parameters and metabolic syndrome: A population-based study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2023, 6, e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavaraputta, S.; Dennis, J.A.; Ball, S.; Laoveeravat, P.; Nugent, K. Relation of hematologic inflammatory markers and obesity in otherwise healthy participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2016. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2020, 34, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baș Aksu, Ö.; Özkara, F.; Emral, R.; Genç, V.; Çorapçioğlu, D.; Şahin, M. Investigation of the relationship between the triglyceride-glucose index and metabolic and hematological parameters in obese individuals. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 55, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, L.; Lv, J.; Xiong, X. The Clinical significance of Peripheral Blood-related Inflammatory Markers in patients with AE-COPD. Immunobiology 2025, 230, 152903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomacu, M.M.; Trașcă, M.D.; Pădureanu, V.; Bugă, A.M.; Andrei, A.M.; Stănciulescu, E.C.; Baniță, I.M.; Rădulescu, D.; Pisoschi, C.G. Interrelation of inflammation and oxidative stress in liver cirrhosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.H.; Li, R.L.; Li, W.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, T. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A population-based cohort study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1499524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasca, L.F.; Poenaru, E.; Patrascu, N.; Cirstoiu, M.; Vinereanu, D. A comprehensive echocardiographic study of the right ventricular systolic function in pregnant women with inherited thrombophilia. Echocardiography 2020, 37, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandru, F.; Poenaru, E.; Stoleru, S.; Radu, A.M.; Roman, A.M.; Ionescu, C.; Zugravu, A.; Nader, J.M.; Băicoianu-Nițescu, L.C. Microbial Colonization and Antibiotic Resistance Profiles in Chronic Wounds: A Comparative Study of Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Venous Ulcers. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mateescu, L.A.; Savu, A.P.; Mutu, C.C.; Vaida, C.D.; Șerban, E.D.; Bucur, Ș.; Poenaru, E.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Constantin, M.M. The Intersection of Psoriasis and Neoplasia: Risk Factors, Therapeutic Approaches, and Management Strategies. Cancers 2024, 16, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, M.; Dai, L.; Cai, L. Inflammatory risk of albumin combined with C-reactive protein predicts long-term cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes. Aging 2024, 16, 6348–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mohammadshahi, J.; Ghobadi, H.; Matinfar, G.; Boskabady, M.H.; Aslani, M.R. Role of Lipid Profile and Its Relative Ratios (Cholesterol/HDL-C, Triglyceride/HDL-C, LDL-C/HDL-C, WBC/HDL-C, and FBG/HDL-C) on Admission Predicts In-Hospital Mortality COVID-19. J. Lipids 2023, 2023, 6329873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Men, S.; Nan, J.; Yang, Q.; Dong, J. The blood monocyte to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (MHR) is a possible marker of carotid artery plaque. Lipids Health Dis. 2022, 21, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Duan, W.; Yao, X.; Hu, Z.; Fan, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, W.; Li, H. Association of glucose to lymphocyte ratio with the risk of death in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Bai, W.; Gai, N.; Li, J.; Bao, Y. A multi-biomarker machine learning approach for early prediction of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, A.; Samouda, H.; Dohet, F.; Loap, S.; Ellulu, M.S.; Bohn, T. Common and Novel Markers for Measuring Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Ex Vivo in Research and Clinical Practice-Which to Use Regarding Disease Outcomes? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekroos, K.; Lavrynenko, O.; Titz, B.; Pater, C.; Hoeng, J.; Ivanov, N.V. Lipid-based biomarkers for CVD, COPD, and aging—A translational perspective. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020, 78, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Im, S.S. Decoding Health: Exploring Essential Biomarkers Linked to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.K.; Thanusha, G.; Chong, P.P.; Chuah, C. The Power of Antibodies: Advancing Biomarker-Based Disease Detection and Surveillance. Immunol. Investig. 2025, 54, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalar, I.; Le, T.H.; Silber, A.; O’Hara, M.; Abdallah, B.; Parikh, M.; Busch, R. The role of blood testing in prevention, diagnosis, and management of chronic diseases: A review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 368, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, A.; Poenaru, E.; Dimitriu, M.C.T.; Zaharia, C.; Ionescu, C.A.; Navolan, D.; Furău, C.G. Obstetrical Soft Tissue Trauma during Spontaneous Vaginal Birth in the Romanian Adolescent Population—Multicentric Comparative Study with Adult Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstündağ, Y.; GKazanci, E.; Koloğlu, R.F.; Çağlak, H.A.; Yildirim, F.; YArikan, E.; Huysal, K. A Retrospective Study of Age-Defined Hematologic Inflammatory Markers Related to Pediatric COVID-19 Diagnosis. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2022, 44, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erhunmwunse, R.U.; Efede, I.M.; Ehiaghe, F.A. Variations in Hematological and Inflammatory Parameters among Smokers and Non-Smokers in Benin City. Int. J. Res. Rep. Hematol. 2025, 8, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al., 2022 [16] | Atherosclerosis |

| LMR (p = 0.005), NLR (p = 0.001), and SII (p = 0.002) associated significantly with plaque enhancement, but only LMR showed a strong negative linear correlation with the contrast ratio (r = 0.716, p < 0.001). A statistically significant association with symptomatic disease was observed for NLR (p = 0.011) and LMR (p = 0.001). LMR was independently associated with symptomatic disease (OR - 0.625, 95% CI 0.421–0.928, p = 0.02). For predicting symptomatic plaque, LMR yielded sensitivity of 80.0%, specificity of 70.6%, and AUC of 0.765 (cut-off: LMR ≤ 4.0). |

| Vaseghi et al., 2022 [17] | FH |

| PLR was significantly elevated (p = 0.003) in FH patients compared to controls and higher in probable/definite FH than in possible FH (p < 0.001). The associations remained statistically significant after applying three models of adjustment for confounding variables (comparison with non-FH - p = 0.026, p = 0.032, p = 0.013, for comparison with possible FH - p = 0.002, p = 0.007, p = 0.029). Without being statistically significant, NLR was higher in the FH group, and RPR was lower among FH patients. Linear regression showed a non-significant independent association between RPR and total cholesterol in patients with FH (p < 0.001). |

| Urbanowicz et al., 2024 [18] | Coronary artery disease |

| NLR (OR = 2.06, p < 0.001, CI 95% = 1.39–3.05) and SIRI (OR = 11.65, p < 0.001, CI 95%= 4.22–32.16) associated with complex coronary artery disease. After logistic multiple regression analysis, SIRI associated with coronary artery disease (OR = 5.52, p = 0.02, CI 95% = 1.89–16.15). A SIRI above 1.21 indicated the patients that had coronary disease (AUC - 0.725, p < 0.001, sensitivity - 49.19%, specificity - 85%). |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kamrani et al., 2025 [19] | Depression |

| In depressed patients, no significant associations were observed among DII higher scores and hematologic ratios. |

| Ceyhun et al., 2022 [20] | Adult ADHD |

| There were no significant results for these markers in ADHD patients compared to controls. Hyperactivity scores correlated positively with SII (r = 0.247, p = 0.034). |

| Sewell et al., 2021 [21] | Major psychiatric disorders |

| For MDD PRS, initial associations of NLR and PLR with genetic risk disappeared after controlling lifestyle covariates. For SCZ PRS, significant negative associations were identified with NLR, PLR, and MLR. For BD PRS, the only significant result after full adjustment was a negative association with PLR. |

| Wei et al., 2022 [22] | Affective disorders |

| Among the whole group of patients with affective disorders, only RPR was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Even after corrections, PLR, SII, and RPR values were significantly different between patients with MDD and controls (p < 0.001 for PLR, p = 0.04 for SII and p < 0.001 for RPR) and patients with BD and controls (p < 0.001 for PLR, p < 0.001 for SII and p < 0.001 for RPR). Patients with manic episodes of BD had the highest SII values. Patients with major depressive disorder had the highest PLR. PLR (p < 0.001) and SII (p < 0.001) had a statistically significant difference between patients with BD and those with MDD. |

| Qiu et al., 2024 [23] | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression |

| OR was 17.351 (p = 0.007) for the association of NLR with schizophrenia. NLR was a predictive factor for schizophrenia (AUC-0.625, p < 0.001, critical value 2.123, sensitivity-89.7%, and specificity-35.8%). |

| Rog et al., 2025 [24] | Anorexia nervosa |

| NLR (AUC-0.745), MLR (AUC-0.785), SII (AUC-0.736), and SIRI (AUC-0.803) differed significantly among the responders and non-responders to treatment among this group of patients. |

| Ninla-Aesong et al., 2024 [25] | Major depressive disorder |

| NLR, PLR, SII, and SIRI had higher values in patients with MDD, compared to healthy controls (p < 0.0001 for each biomarker). MLR was also higher in MDD, without being statistically significant (p = 0.162). All investigated biomarkers were higher in patients with suicide attempts, but only MLR (p = 0.005) and SIRI (p = 0.012) were statistically significant. A cut-off value of 1.645 for NLR (AUC = 0.73, p-value < 0.0001, sensitivity = 71.2%, specificity = 67.2%) and a cut-off value of 428.67 for SII (AUC = 0.74, p-value < 0.0001, sensitivity = 75.5%, specificity = 62.5%) had diagnostic relevance for MDD. A cut-off of 1.82 for NLR could differentiate patients with MDD with suicide attempts (AUC = 0.71, p-value < 0.0001, sensitivity = 72.1%, specificity = 65.6%). For PLR, a cut-off value of 135.77 could differentiate non-responders to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (AUC = 0.74, p = 0.033, sensitivity = 83.8%, specificity = 62.5%). |

| Kim et al., 2021 [26] | Bell’s palsy |

| Patients had significantly higher values of NLR (p = 0.007) and PLR (p = 0.012). NLR positively correlated with the grade of facial paralysis (r = 0.661, p < 0.0001). |

| Li et al., 2024 [27] | Parkinson’s disease |

| Patients had higher levels of NLR and lower levels of LMR, both being significantly associated with the disease (p < 0.001). NLR had an AUC of 0.6200, a sensitivity of 50.54%, and a specificity of 71.5%, while for LMR, AUC was 0.6253, with a sensitivity of 48.39% and a specificity of 73%. |

| Stanca et al., 2022 [28] | Parkinson’s disease |

| NLR (p = 0.04) and PLR (p < 0.001) had significant differences between the patients and the control group. PLR was correlated with disease stage (p = 0.027) and disease duration (p = 0.001). |

| Dezayee et al., 2024 [29] | Multiple sclerosis |

| Each of the investigated biomarkers had statistically significant elevated levels (p < 0.001) in patients with multiple sclerosis. |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al., 2025 [30] | Tuberculosis |

| The LTBI group had significantly lower values of the SII (p = 0.038) and PLR (p = 0.003) and non-statistically significant lower values of MLR (p = 0.562) and NLR (p = 0.352) ratios. After applying models for adjustments for confounding variables, all the investigated biomarkers correlated statistically with LTBI status (SII: p < 0.001 and p = 0.013; NLR: p < 0.001 and p < 0.008; PLR: p < 0.001 and p = 0.023; MLR: p < 0.001 and p = 0.002). |

| He et al., 2025 [31] | Tuberculosis |

| The patients with TB and diabetes mellitus had significantly lower MLR (p < 0.001), PLR (p < 0.001), NLR (p < 0.001), SII (p < 0.001), and SIRI (p < 0.001) values. Low MLR (p = 0.021) and PLR (p = 0.003) were classified as independent risk factors for developing diabetes mellitus. For the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, the AUC for MLR was 0.600, and for PLR, it was 0.584. |

| Buttle et al., 2021 [32] | Tuberculosis |

| MLR was higher in male patients. |

| Saglam et al., 2023 [33] | Helicobacter pylori infection |

| Patients positive for Helicobacter pylori had significantly higher PLR values (p = 0.023) and significantly lower NLR values (p = 0.023). Among patients with and without esophagitis, no significant differences were observed. |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [34] | Hepatitis B |

| PWR was significantly lower among non-survivors (p = 0.037). There was also a negative correlation between the PWR and MELD scores (r = −0.277, p = 0.001). For mortality in the context of HBV decompensated cirrhosis, the AUC was 0.721 for PWR, with a sensitivity of 73.3% and a specificity of 63.8%, for a cut-off value of 14.2. |

| Li et al., 2020 [35] | Hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis |

| NLR (p < 0.001) and MLR (p = 0.004) were significantly lower in patients who survived. AUC for NLR was 0.804 (p < 0.001, cut-off = 3.78), with a sensitivity of 70.8% and a specificity of 82%. AUC for MLR was 0.681, (p = 0.003, cut-off = 0.59), with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 60.7%. |

| Bilir et al., 2022 [36] | Persistent human papilloma virus infection |

| All the parameters were higher in the patients with persistent infection (NLR - p = 0.0001, PLR - p = 0.005, MLR - p = 0.0001, SIRI - p = 0.0001). For the detection of persistent infection, the AUC of SIRI was 0.71 (cut-off 0.65), with a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 79%. |

| Bhattacharya et al., 2022 [37] | Periodontitis |

| Higher NLR values were observed in patients with periodontitis (p = 0.013). |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aksoy Sarac et al., 2023 [38] | Alopecia areata |

| MLR and PLR were significantly higher in AA patients compared with controls (p < 0.001). PLR correlated positively with disease duration (r = 0.297, p = 0.013) and severity (r = 0.315, p = 0.008). Diagnostic utility: MLR (cut-off = 0.216; AUC = 0.873) demonstrated high sensitivity (85.7%) and specificity (70%), while PLR (cut-off 111.715; AUC = 0.727) showed moderate usefulness, with 75.7% sensitivity and 58.6% specificity. Logistic regression indicated that elevated MLR (p < 0.001) and PLR (p = 0.037) values increased the risk of AA by 6.30- and 2.76-fold, respectively, supporting their role as good and moderately useful diagnostic tests for AA. |

| Demirbas et al., 2025 [39] | Acne vulgaris |

| NLR and MLR decreased overtime with isotretinoin therapy (p < 0.001). |

| Pala et al., 2023 [40] | Acne vulgaris |

| MLR was significantly higher in the acne group compared to controls (p = 0.044). |

| Rostamian et al., 2024 [41] | Psoriasis |

| DAPSA scores exhibited statistically significant associations with both NLR (p = 0.005) and PLR (p = 0.048). |

| Amer et al., 2024 [42] | Psoriasis |

| There were no significant variations in NLR between the groups. |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okuyan et al., 2024 [43] | Insulin resistance in children |

| Patients with insulin resistance had elevated values of NLR (p < 0.001), PLR (p = 0.001), and SII (p < 0.001) compared with those without. Patients with vitamin D within normal range had lower NLR (p < 0.001), PLR (p = 0.002) and SII (p < 0.001). |

| Zhu et al., 2022 [44] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| In this patient cohort, NLR, PLR, and MLR were not significantly associated with the development of diabetic macular edema. |

| Taban et al., 2025 [45] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Diabetic patients had higher NLR and PLR, with mean values of 3.12 versus 1.66 for NLR (p = 0.001) and 249.05 versus 131.41 for PLR (p = 0.001). Obese diabetic patients exhibited even more pronounced elevations in these markers (NLR - p = 0.001, PLR - p = 0.001). Both NLR (OR = 1.28, p < 0.001) and PLR (OR = 1.02, p = 0.004) showed significant positive associations with HbA1c levels. |

| Chollangi et al., 2023 [46] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| NLR value was significantly higher in diabetic patients with microalbuminuria compared to those without (p < 0.001). NLR correlated significantly and positively with HbA1c in patients with microalbuminuria (r = 0.662, p < 0.001). To detect microalbuminuria in diabetic patients, AUC for NLR was 0.859, with an optimal cut-off value of 2.13, yielding a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 77.3%. |

| Amaeshi et al., 2024 [47] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| The mean NLR was similar between both groups of T2DM patients. The PLR values were slightly higher among patients, but it was not statistically significant. Neither NLR nor PLR were correlated with HbA1c levels. |

| Shyam V et al., 2023 [48] | Diabetes mellitus |

| Both NLR (p = 0.0001) and PLR (p = 0.038) were significantly elevated in diabetic patients with DVT compared to those without. NLR correlated with HbA1c (r = 0.7361, p = 0.001). An NLR cut-off of 2.83 achieved 67% sensitivity and 92% specificity for detecting DVT in diabetic patients. (AUC = 0.833) For PLR, the optimal threshold was 131.46, yielding 56% sensitivity and 90% specificity (AUC = 0.762). |

| Uslu et al., 2025 [49] | Diabetes mellitus |

| PLR was significantly lower in the diabetic patients (p = 0.011). In the diabetic group, severity of PNP showed positive correlations with NLR (p = 0.001) and SIRI (p = 0.005) and negative correlations with LMR (p = 0.037). |

| AlShareef et al., 2024 [50] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| HbA1c was positively correlated with NLR (r = 0.193, p = 0.007). The study found that patients with diabetic neuropathy exhibited significantly higher NLR (p = 0.011). |

| Dascalu et al., 2023 [51] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Significantly elevated NLR (p = 0.005), MLR (p = 0.001) and SII (p = 0.013) were identified in the proliferative diabetic retinopathy patients, compared to the other two groups. For predicting proliferative diabetic retinopathy, NLR achieved a sensitivity of 40% and a specificity of 86.9%, AUC = 0.662, for a cut-off value of 3.18 (p = 0.001), MLR had sensitivity of 35.6% and a specificity of 92.9%, AUC = 0.643, for a cut-off value of 0.364 (p = 0.006), and SII had a sensitivity of 35.6% and a specificity of 85.7%, AUC = 0.627, for a cut-off value of 763.8 (p = 0.015). NLR (OR = 1.645, p = 0.002) and MLRx10 (OR = 1.662, p = 0.0017) were identified as potential risk factors. |

| Aygun et al., 2024 [52] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| HbA1c positively correlated with NLR (r = 0.18, p < 0.01). |

| Patro et al., 2025 [53] | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| PLR and SII were significantly higher in patients with proteinuria (p < 0.001). |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domerecka et al., 2022 [54] | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Patients with autoimmune hepatitis had elevated MPR (p = 0.0004), RPR (p = 0.0007), NLR (p < 0.0001). PLR and RLR achieved perfect discrimination for detecting autoimmune hepatitis, with AUC = 1.00 (sensitivity 100%, specificity 100%, p < 0.0001). For the other biomarkers, the following performances were obtained: RPR – AUC = 0.75 (sensitivity 56.67%, specificity 90%, p = 0.0001), NLR – AUC = 0.84 (sensitivity 70%, specificity 96.67%, p < 0.0001), and MPR – AUC = 0.77 (sensitivity 66.67%, specificity 76.67%, p < 0.0001). Additionally, MPR (AUC = 0.93), PLR (AUC = 0.86), and RPR (AUC = 0.91) markers demonstrated strong utility in detecting liver fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. |

| Gonzales-Sierra et al., 2023 [55] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| NLR, MLR, PLR, and SIRI were elevated in rheumatoid arthritis patients. These markers were correlated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors. |

| Masoumi et al., 2024 [56] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| NLR (r = 0.21, p = 0.0003) and PLR (r = 0.23, p = 0.0001) correlated with activity scores. NLR (AUC = 0.66, cut-off = 1.85, sensitivity = 81%, specificity = 49%, p < 0.001) and PLR (AUC = 0.64, cut-off = 10.9, sensitivity = 61%, specificity = 68%, p = 0.001) could distinguish between active and remission states of rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Targonska-Stepniak et al., 2021 [57] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| PLR (p = 0.03) was significantly lower in patients with elderly onset, compared with patients with disease onset at a younger age. Both markers associated with various parameters of disease activity. |

| Obaid et al., 2023 [58] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| NMR (p = 0.0001), LMR (p = 0.001), and NLR (p = 0.001) were significantly higher in the patients, compared to the control group and correlated with classic inflammatory markers for rheumatoid arthritis. For diagnosis, NMR had an AUC of 0.861 (cut-off = 4.7, sensitivity = 87%, specificity= 80%, p = 0.0001). LMR had an AUC of 0.807 (cut-off = 4.35, sensitivity = 62.3%, specificity = 90%, p = 0.0001) and NLR (cut-off = 1.35, sensitivity = 57.4%, specificity = 80%, p = 0.008). |

| Cheng et al., 2024 [59] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Only PLR was positively correlated with synovitis (r = 0.419, p = 0.001) and bone erosion (r = 0.252, p = 0.015) at ultrasound. A cut-off value of at least 159.6 associated with an AUC of 0.7868, a sensitivity of 80.95%, and a specificity of 74.24% for synovitis with a GS grade of at least 2. The AUC was 0.7690, with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 83.87%, for a cut-off value of at least 166.1 in identifying synovitis PD Grade 2 and more. |

| Targonska-Stepniak et al., 2020 [60] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| NLR (r = 0.21, 0.25 and 0.24; p = 0.02, p = 0.004, p = 0.008) and PLR (r = 0.25, 0.24 and 0.26; p = 0.004, p = 0.007, p = 0.003) demonstrated positive correlations with all the scores of disease activity indicated by ultrasound, but also with diverse activity parameters. |

| Sahin et al., 2022 [61] | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| NLR was significantly higher in patients with arthritis (p = 0.001). NLR and MLR did not differ significantly between patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and those with other arthritis. |

| Sharma et al., 2025 [62] | Thyroiditis |

| No relevant associations were identified. |

| Okak et al., 2024 [63] | Behçet’s disease |

| For detection of vascular Behçet’s disease, PIV had an AUR of 0.654 (cut-off = 261.6, sensitivity = 75.3%, specificity = 55.4%, p < 0.001). PIV was also a significant risk factor in both univariate and multivariate analysis (OR = 3.791, p < 0.001; OR = 2.758, p = 0.007). NLR and PLR were highlighted as potential risk factors only in univariate analysis and not after multivariate analysis. |

| Kivrakoglu et al., 2025 [64] | Celiac disease |

| SII, NLR, and PLR did not differ statistically significantly among histological stages, but higher values were observed in patients with Marsh Grade 3a and 3b compared with Grade 1 and 2. Lower values of these indices were observed in Grade 3c. |

| Baykal et al., 2024 [65] | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| NLR (p = 0.01), SII (p = 0.048), and SIRI (p = 0.025) were significantly higher in patients compared to controls. Patients with elevated disease activity scores had significantly higher NLR (p = 0.01) and SII (p = 0.048). For predicting disease activity, NLR had an AUC of 0.699 (cut-off = 2.8, sensitivity = 61.2%, specificity = 71.3%, p = 0.031), SII had an AUC of 0.695 (cut-off = 415, sensitivity = 85%, specificity = 76.1%, p = 0.021), SIRI had an AUC of 0.681 (cut-off = 2.56, sensitivity = 83%, specificity = 69.7%, p = 0.004), and AISI had an AUC of 0.782 (cut-off = 328, sensitivity = 78%, specificity = 58.1%, p = 0.006). MLR associated with antibody positivity at disease onset (p = 0.012). |

| Suszec et al., 2020 [66] | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| NLR values were higher in patients with cutaneous and/or mucosal (p = 0.05) and kidney involvement (p < 0.001), and in patients with antibodies against double stranded DNA (p = 0.03). BLR (p < 0.001 and p = 0.01) and MLR (p < 0.001 and p = 0.01) were higher in patients with vasculitis, arthritis, and myositis. ELR (p < 0.001) was higher in patients with vasculitis. PLR was higher in patients with hematological disorders (p = 0.01) and nephritis (p = 0.03). |

| Moreno-Torres et al., 2022 [67] | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| NLR and PLR had higher values in patients than in controls (p < 0.001), but also in patients with anemia, compared to systemic lupus erythematosus patients without anemia (p < 0.0001). Both markers had various associations and correlations with parameters of clinical activity. |

| Ma et al., 2025 [68] | Myopathy |

| Patients with immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy had statistically significant higher MLR than healthy controls (p = 0.0084) and lower than patients with dermatomyositis (p = 0.0089). Patients with dermatomyositis had significantly higher NLR compared to patients with immune-mediated necrotizing-myopathy (p = 0.0395). Compared to healthy controls, patients with dermatomyositis had higher PLR (p = 0.0042). For differentiating the two conditions, NLR had an AUC of 0.6984, and MLR had an AUC of 0.7487. |

| Omer et al., 2025 [69] | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| NLR (p < 0.0001) was significantly higher in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. To differentiate between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, an AUC of 0.733 was obtained for NLR (cut-off = 2.11, sensitivity = 67.16%, specificity = 76.92%, p < 0.0001). |

| Huang et al., 2022 [70] | Vasculitis |

| PLR did not correlate with the activity score. PLR was associated with lower risk of end-stage kidney disease (p = 0.038, HR = 0.518). |

| Poenariu et al., 2023 [71] | Ulcerative colitis |

| Various significant associations were identified for all of the markers (except for dNLR) and disease activity and extent. MCVL had an AUC of 0.709 (cut-off = 45.63, sensitivity = 73.33%, specificity = 58.7%, p = 0.025), and PLR had an AUC of 0.704 (cut-off = 129.4, sensitivity = 73.33%, specificity = 54.35%, p = 0.047). |

| Cui et al., 2022 [72] | Ulcerative colitis |

| NLR, PLR and LMR varied significantly among subgroups of patients (p < 0.001) and correlated with endoscopic activity (NLR and PLR positively, LMR negatively). For disease activity, NLR had an OR of 2.42 and 2.38, depending on the scoring system. All the markers had good diagnostic performance to differentiate activity from remission, with AUC ranging from 0.739 to 0.796. |

| Pana et al., 2024 [73] | Nephropathies |

| PLR was significantly higher in patients with membranous nephropathy (p = 0.01). Higher NLR was associated with mortality in patients with membranous nephropathy. |

| Bekir et al., 2021 [74] | Sarcoidosis |

| NLR was higher in patients with chronic disease, compared to those with remission (p = 0.006). |

| Yilmaz et al., 2025 [75] | Osteoarthritis |

| Values of SII of 627.9 can differentiate severe forms of osteoarthritis with limited performances (sensitivity - 42.5% and specificity - 70.6%, AUC = 0.596, p < 0.001). OR for SII was 1.623 in multivariate analysis, p = 0.003. |

| Study | Condition | Study Details | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keyif et al., 2025 [76] | Endometrial polyps |

| PLR (p = 0.015) was significantly higher in patients with endometrial polyps and was an independent predictor for this condition (p = 0.045). |

| Nouri et al., 2025 [77] | Endometriosis |

| Females with endometriosis had significantly higher NLR (p < 0.001). NLR had a sensitivity of 83.4% and a specificity of 52.5% for a cut-off of 1.5 (AUC - 0.699). |

| Pau et al., 2023 [78] | Sleep apnea |

| NLR (r = 0.12, p = 0.05) and SII (r = 0.115, 0.006) were positively correlated with apnea hypopnea index. NLR (r = 0.16, p = 0.0075), SII (r = 0.16, p = 0.009), SIRI (r = 0.15, p = 0.013), and AISI (r = 0.15, p = 0.015) were positively correlated with the oxygen desaturation index. Oxygen saturation was correlated with NLR (r = −0.21, p = 0.0002), SII (r = −0.21, p = 0.0006), SIRI (r = 0.24, p = 0.0001), AISI (r = −0.23, p = 0.0002), and MLR (r = −0.153, p = 0.014). SIRI was independently associated with lower oxygen saturation (r = −0.1935, p = 0.0087). |

| Chen et al., 2024 [79] | Anemia |

| A significantly positive correlation between the individuals’ risk of anemia and the value of SII was identified (OR = 1.51, p < 0.001). |

| Atik et al., 2024 [80] | Mediterranean fever |

| MLR (AUC: 0.700), NLR (AUC: 0.801), and SII (AUC: 0.858) were defined as very sensitive parameters in determining sacroiliitis in patients with Mediterranean fever. |

| Ciceri et al., 2025 [81] | Beta thalassemia |

| Patients with beta thalassemia had significantly increased NPR (p = 0.001), dNLR (p = 0.001), NLR (p = 0.010), and SII (p = 0.038). |

| Najafzadeh et al., 2023 [82] | Metabolic syndrome |

| PMR was significantly lower in participants with metabolic syndrome. PLR and PMR were significantly higher in females than in males with metabolic syndrome (p < 0.001). |

| Thavaraputta el al., 2020 [83] | Obesity |

| The investigated biomarkers were significantly associated with higher body mass index, with variations depending on the gender. |

| Bas Aksu et al., 2025 [84] | Obesity |

| No meaningful association observed for these parameters in patients grouped by HBA1c levels. |

| Li et al., 2025 [85] | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| The investigated biomarkers can be used to identify patients with moderate-to-severe diseases. Higher levels associated with acute exacerbations and readmission to hospital. Highest diagnostic accuracy for moderate-to-severe disease was obtained from combining the 5 biomarkers, with a cut-off value of 0.38, obtaining an AUC of 0.837. |

| Pomacu et al., 2021 [86] | Liver cirrhosis |

| NLR, MLR, and PLR had significantly higher values in patients who had cirrhosis related to hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Patients with toxic hepatitis had high PLR values compared to controls. NLR and MLR can indicate pro-inflammatory hepatic status. |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [87] | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| NLR had positive linear associations with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, predicting mortality in these patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dugăeşescu, M.; Andrei-Bitere, I.; Baciu, M.-R.; Dănescu, E.; Liţescu, A.; Vidroiu, S.-T.; Manu, A.; Constantin, M.M.; Roșca, I.; Stoleru, S.; et al. Hematological Inflammatory Markers and Chronic Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Hemato 2025, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040042

Dugăeşescu M, Andrei-Bitere I, Baciu M-R, Dănescu E, Liţescu A, Vidroiu S-T, Manu A, Constantin MM, Roșca I, Stoleru S, et al. Hematological Inflammatory Markers and Chronic Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Hemato. 2025; 6(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleDugăeşescu, Monica, Iulia Andrei-Bitere, Marina-Raluca Baciu, Eva Dănescu, Alexandru Liţescu, Simina-Teodora Vidroiu, Andrei Manu, Maria Magdalena Constantin, Ioana Roșca, Smaranda Stoleru, and et al. 2025. "Hematological Inflammatory Markers and Chronic Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives" Hemato 6, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040042

APA StyleDugăeşescu, M., Andrei-Bitere, I., Baciu, M.-R., Dănescu, E., Liţescu, A., Vidroiu, S.-T., Manu, A., Constantin, M. M., Roșca, I., Stoleru, S., & Poenaru, E. (2025). Hematological Inflammatory Markers and Chronic Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Hemato, 6(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040042