1. Introduction

Hydrogels are composed of natural or synthetic polymers that are crosslinked through physical and chemical interactions. These materials are typically soft and compliant, making them particularly attractive for biomedical applications. Stimulus-responsive hydrogels have garnered significant attention recently because they can be used as smart materials for soft actuator applications [

1]. This is due to their ability to undergo reversible structural changes in response to external stimuli, including temperature [

2], pH [

3], ionic strength [

4], solvent composition [

5], electric field [

6], and light [

7]. Similar to biological tissues, such as sclera [

8,

9], electroactive polymers (EAPs) represent a specialized class of smart materials capable of converting electrical energy into mechanical deformation. This unique property makes EAPs particularly suitable for applications such as artificial muscles and chemo–electro–mechanical actuators, where large swelling and contraction responses are desirable.

Several studies have been carried out to characterize the electroresponsive behavior of hydrogel systems. For example, Yuk and Lee reported reversible bending of crosslinked acrylamide gels induced by electric current in aqueous NaCl solution [

10]. Migliorini et al. developed an electroresponsive hydrogel based on sodium 4–vinylbenzenesulfonate (Na-4-VBS) that functioned as a fast actuator, bending toward the cathode in NaCl solution [

11]. Shiga and Kurauchi investigated the deformation behavior of polyelectrolyte gels under electric field influence [

12]. Ma et al. prepared an amphoteric interpenetrating polymer network composed of crosslinked gelatin with glutaraldehyde (GA), which demonstrated bidirectional bending toward either cathode or anode depending on the pH of the surrounding Na

2SO

4 solution [

13]. Similarly, Shiga et al. developed electroactive hydrogels by blending polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyacrylic acid (PAA), which exhibited cathodic bending in buffer solution [

14].

Despite significant advances in creating electroactive hydrogels, their application in biological and pharmaceutical fields remains limited due to poor biocompatibility and potential toxicity of synthetic polymers [

15]. Most existing electroactive hydrogels contain synthetic components that may pose biocompatibility concerns. Additionally, many electroactive hydrogels exhibit unidirectional bending behavior, i.e., responding only toward either the anode side [

16,

17] or the cathode side [

18]. Furthermore, the electrosensitivity of some hydrogels can be compromised because of insufficient ionic groups in their synthetic polymer constituents, which could limit their electromechanical response within specific pH ranges [

19].

Chitosan (CS), a naturally occurring cationic polysaccharide, offers significant advantages for electroactive hydrogel development. Its unique cationic nature enables the formation of interpenetrating networks with negatively charged polyanions, while its demonstrated biocompatibility and non-toxicity make it highly suitable for medical applications [

20]. The cationic amino groups in chitosan readily form polyelectrolyte complexes (PECs) with anionic materials [

21]. The electroactive behavior of chitosan-based hydrogels is pH-dependent, with amphoteric chitosan/polyanion hydrogels exhibiting directional bending toward either anode or cathode, based on the pH of the surrounding solution. Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) is a natural anionic polyelectrolyte derived from cellulose, containing carboxyl methyl groups (-CH

2COOH). The combination of chitosan and CMC has attracted considerable interest in biomedical applications due to their unique biodegradability, biocompatibility, and pH sensitivity characteristics.

Chen et al. developed a pH-sensitive amphoteric polyelectrolyte hydrogel film through solution blending of CS and CMC, which demonstrated bidirectional bending behavior [

22]. However, their study did not investigate the effects of component volume ratios, the magnitude of the electric field, and the electrode distance. Optimizing the electromechanical bending response of EAPs through compositional ratio adjustment represents a critical aspect in designing artificial muscles and actuators [

23,

24]. The objective of the current study was to investigate the effects of feed composition, i.e., CS/CMC volume ratio, electrode distance (ED), and applied electric voltage on the electromechanical bending behavior of CS/CMC hydrogels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (molecular weight: 700 kDa, deacetylation degree: 90%) and GA 25% solution in H2O were purchased from Chemsavers (Bluefield, VA, USA). Carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt (NaCMC), potassium chloride, boric acid, and phosphoric acid were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and acetic acid were obtained from Ward’s Science (New York, NY, USA) and VWR (Radnor, PA, USA), respectively.

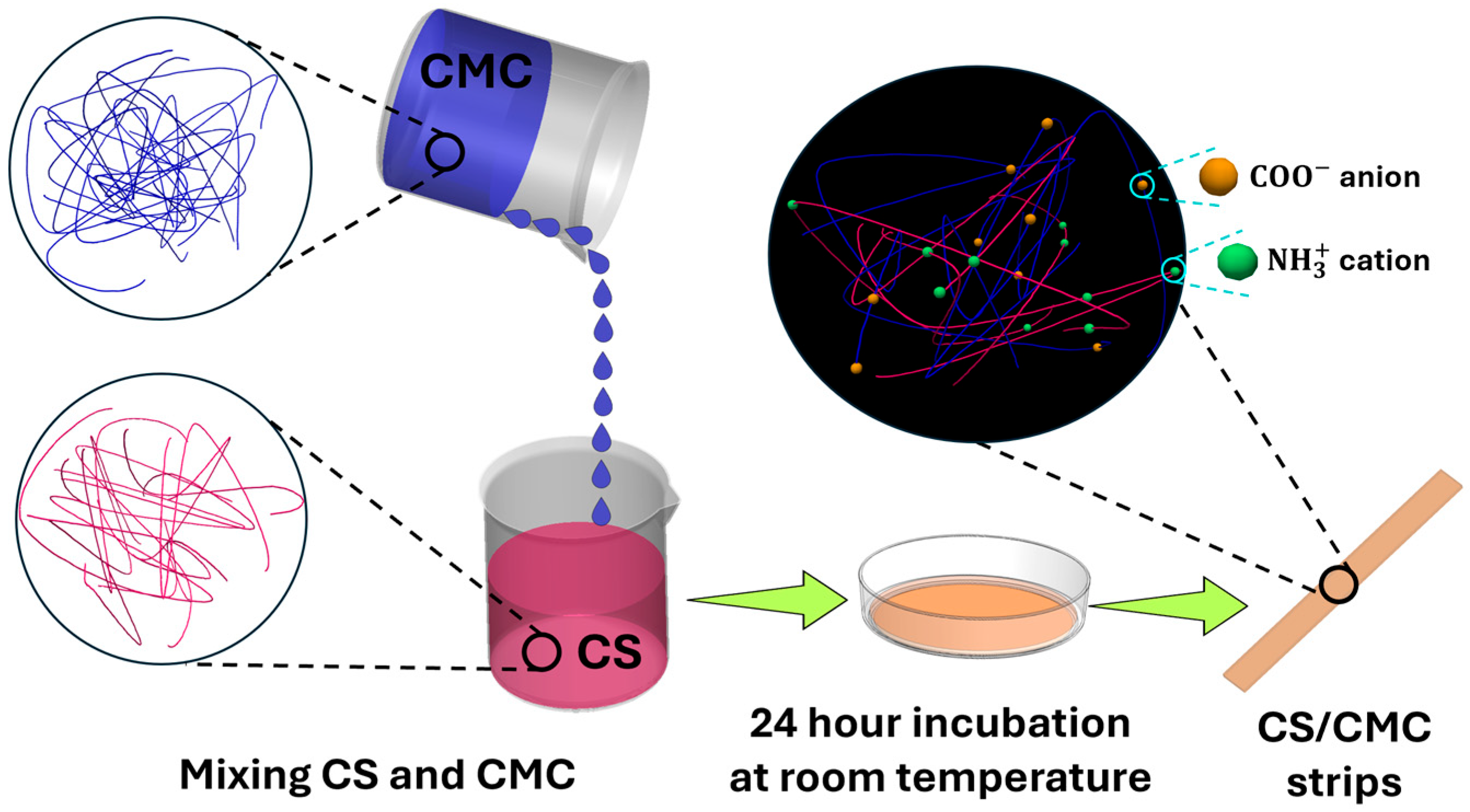

2.2. Synthesis of CS/CMC Hydrogels

A 2% (

w/

v) CS solution was prepared by dissolving CS in 2% (

) acetic acid aqueous solution, and NaCMC was dissolved in deionized water to make a 2% (

) NaCMC solution. Then, NaCMC solution was added dropwise into the CS solution (CMC/CS volume ratio = 2:3) at 60 °C under stirring. GA was added into the solution (2% mole of the amino groups on CS) to crosslink the CS. After complete mixing at 60 °C for 2 h, the mixture was poured into a petri dish and left at room temperature overnight to form a dried polymer film, as shown in

Figure 1. Finally, the dried films were put into a 0.5%

) NaOH aqueous solution to remove the remaining acetic acid and were then washed with deionized water [

22].

To investigate effects of positive/negative charge balance on the swelling behavior and electromechanical bending of CS/CMC hydrogels, the same procedure was used to prepare two additional mixtures with CMC/CS volume ratios = 3:2 and 3:3. A CS/CMC ratio of 2:3 leads to CMC-dominant systems, due to the presence of excess anionic carboxyl groups, which enable investigation of the behavior of polyanionic networks. On the other hand, a CS/CMC ratio of 3:2 yields CS-dominant systems, attributed to the excess cationic amino groups, thereby allowing for the exploration of characteristics of polycationic networks. Finally, a composition ratio of CS/CMC = 1:1 represents a balanced stoichiometric ratio in which electrostatic interactions between NH3+ and COO− groups are maximized. These three CS/CMC hydrogels, each with a distinct composition, facilitate understanding of how variation in positive/negative charge balance affects their swelling behavior and bending performance.

Hydrogel strips measuring 20 mm (length), 2 mm (width), and 0.2 mm (thickness) were prepared. The length and width of the hydrogel strips were selected based on our preliminary studies. In particular, we systematically altered the length and width of hydrogel strips in different steps to ensure that they had sufficient mechanical properties for bending under the electric field without losing their structural integrity. The optimum aspect ratio (defined as the ratio of width and length) was found to be about 0.1. After the preparation and drying of the CS/CMC films, their thickness was about 0.2 mm. Here, all hydrogel strips were tested at their equilibrium swelling state.

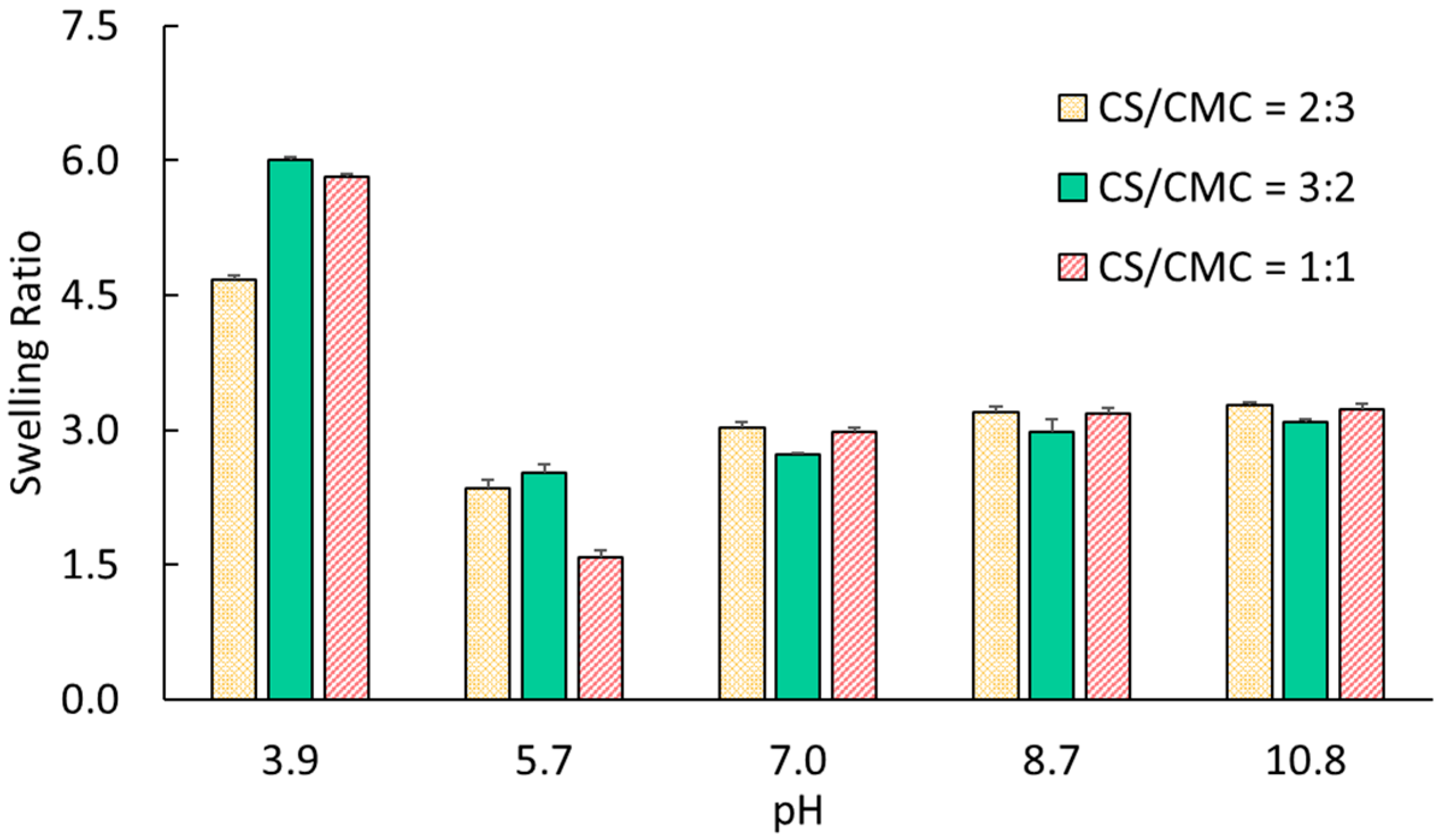

2.3. Effect of pH on Swelling of CS/CMC Hydrogels

The hydrogels were immersed in 0.1 M Britton–Robinson buffer solutions with different pH values. Specifically, pH = 3.9 was selected to create a predominantly polycationic environment due to the complete protonation of chitosan amino groups (pKb ≈ 6.5 for NH3+) and the concurrent preservation of the protonated state of carboxyl groups (pKa ≈ 4.6 for CMC). Solutions with pH = 5.7 allowed investigation of the behavior of hydrogels at the critical transition zone, where both functional groups undergo ionization. At this pH, amino groups begin deprotonating while carboxyl groups start ionizing, creating optimal conditions for NH3+-COO− electrostatic interactions. The solutions with pH = 7.0 were considered as the neutral reference point for the behavior of CS/CMC hydrogels. Solutions with pH = 8.7 created a predominantly polyanionic environment because of the deprotonation of amino groups to NH2, while maintaining full ionization of carboxyl groups to COO−. Finally, an extremely basic condition (pH = 10.8) was used to verify the stability of the polyanionic state and examine the behavior of gels at their maximum anionic charge density. These pH values span the full ionization range of existing functional groups, enabling exploration of the electromechanical behavior of CS/CMC networks as they shift from exhibiting polycationic to polyanionic characteristics.

The samples were taken out of the buffer solution at regular intervals. After removing the excess solution from their surface using filter paper, the weight of the swollen samples was obtained by a digital scale. The swelling ratio, SR, was defined as

where

Ws and

Wd are the swollen and dry weights of strips, respectively [

25].

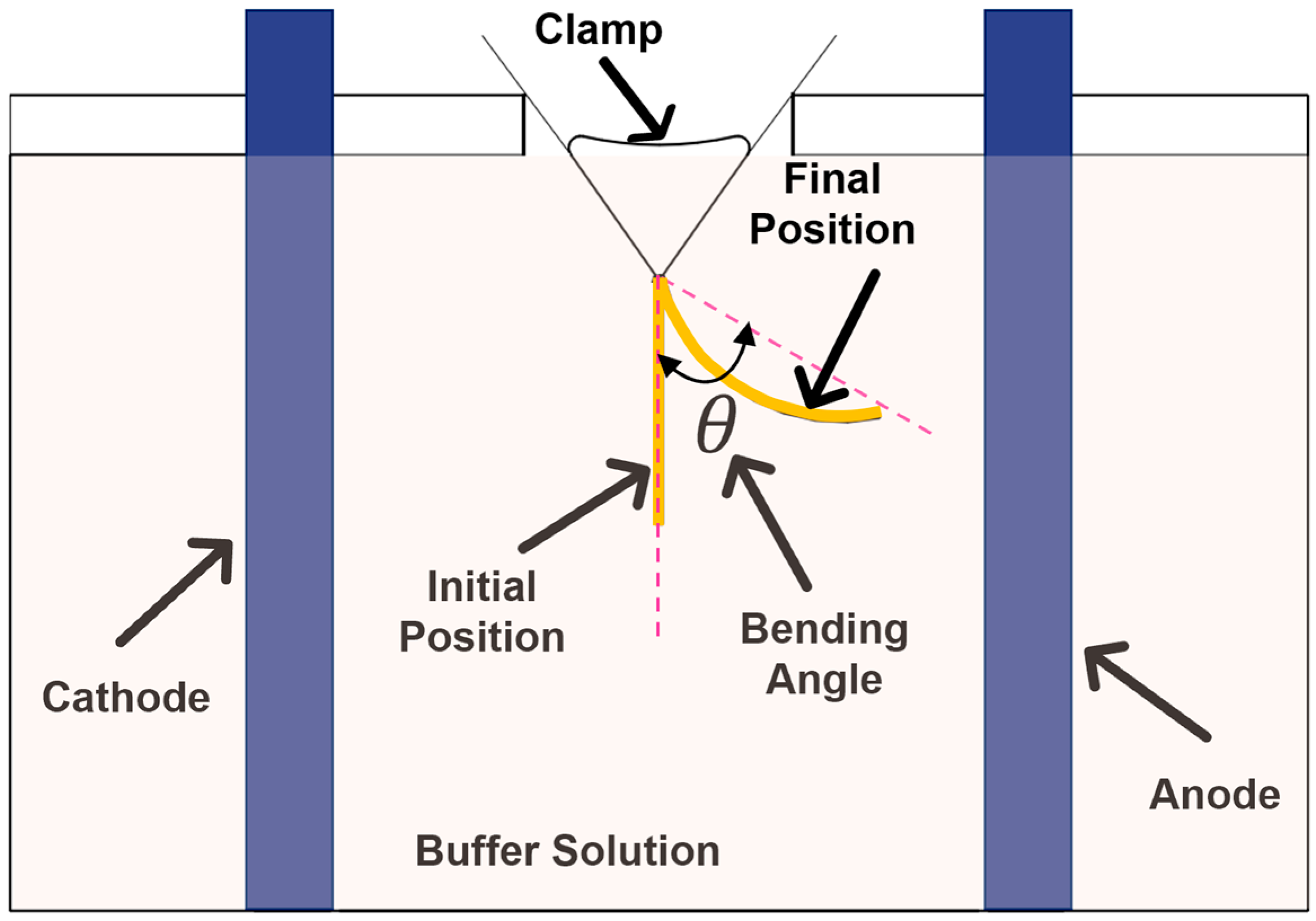

2.4. Bending Angle Measurement

The samples were mounted centrally between two parallel carbon electrodes 50 mm apart.

Figure 2 shows a schematic sketch of the setup used for the experiments. A B&K Precision DC power supply was used (Yorba Linda, CA, USA) for applying the electric field. The range of voltage

was determined through preliminary safety and performance optimization studies that showed that voltages below 15 V did not generate measurable bending deformation, when the electrode distance was 5 cm. The upper limit of 25 V was established to prevent visualization issues; significant bubble formation was observed at voltages above 30 V in our preliminary testing. The variation in voltage between 15 V and 25 V provided a favorable balance between achieving pronounced electroactive bending deformation and maintenance of system stability.

The amount of bending was quantified by measuring the angle that the tip of the hydrogel strips made with respect to their original position after the application of the electric voltage. The bending angle of the strips at the original location was defined as 0° [

26]. The position of the hydrogel strips was recorded using a Nikon digital camera (Melville, NY, USA). The bending angle in different time steps was calculated from these images.

2.5. Mathematical Modeling of Electroactive Bending Behavior

The experimental electroactive response of CS/CMC hydrogels was numerically modeled using the following exponential function

where

θ(

t) represents the bending angle at time

t,

is the maximum bending angle at equilibrium, and

τ is the time constant that determines the rate at which the bending deformation reaches equilibrium. The model parameters were determined through the nonlinear least-squares fitting of Equation (2) to the experimental data.

4. Discussion

The pH-sensitive hydrogels contain dissociable acidic or basic functional groups that undergo ionization at specific pH thresholds. This ionization process defines the density of fixed charges, either positive or negative, on the polymer chains forming the solid backbone of the hydrogels. The existence of these fixed charged groups causes the migration of counterions from the surrounding medium into the hydrogels. In other words, the high ionic concentration gradient between the inside and outside of gels drives solvent molecule influx into the gel networks, causing them to swell. The volumetric expansion of the gel matrix is necessary for creating an equilibrium state between internal and external environments. The network expansion is the result of osmotic pressure difference and electrostatic repulsion between similarly charged functional groups within the networks. As the hydrogel swelling progresses, the osmotic pressure gradually decreases, and a state of prestress evolves in the fiber network domain [

29,

30]. Basically, the elastic contraction forces generated in the fibers of crosslinked networks, resulting from the swelling of the domain, increase until an equilibrium state is reached, defining the final swelling state of the hydrogels [

19,

25].

The primary molecular species governing the swelling behavior and electromechanical response of CS/CMC hydrogels are carboxylate anions (COO

−, pK

a = 4.6) and amino groups (NH

2, pK

b = 6.5) [

31]. At pH ≈ 3.9, CS amino groups predominantly exist as protonated ammonium cations (NH

3+), while CMC carboxylic groups remain largely protonated (COOH). This creates strong NH

3+-NH

3+ electrostatic repulsion as the dominant interaction, explaining the elevated swelling ratios observed for all compositions (4.67–6.00). The highest swelling (6.00) was observed in gels with CS/CMC = 3:2, correlating with their higher chitosan content. As the pH rises to about 5.7, both functional groups undergo gradual charge transitions. NH

3+ begins deprotonating to NH

2, while COOH groups ionize to COO

−. This creates a complex ionic environment containing NH

3+, NH

2, COO

−, and COOH species [

32]. The resulting NH

3+-COO

− electrostatic attractions and COOH-NH

2 hydrogen bonding significantly reduce inter-chain repulsion, leading to a substantial decrease in the swelling ratio (1.58–2.53). Our results agree with this explanation, as the gels with CS/CMC = 1:1 demonstrated the lowest swelling (1.58) at this pH, indicating optimal interaction between CS and CMC chains at the 1:1 volume ratio.

At pH > 7.0, the networks undergo further ionic transformation with complete deprotonation of amino groups to NH2 and full ionization of carboxyl groups to COO−. This creates predominantly polyanionic networks with COO−-COO− repulsion as the principal interaction, resulting in moderate swelling ratios (2.72–3.28). In agreement with this argument, the gradual increase in the swelling observed in solution with higher pH (i.e., 8.7 to 10.8) should have stemmed from the enhanced ionization of carboxylate groups and the subsequent electrostatic repulsion forces.

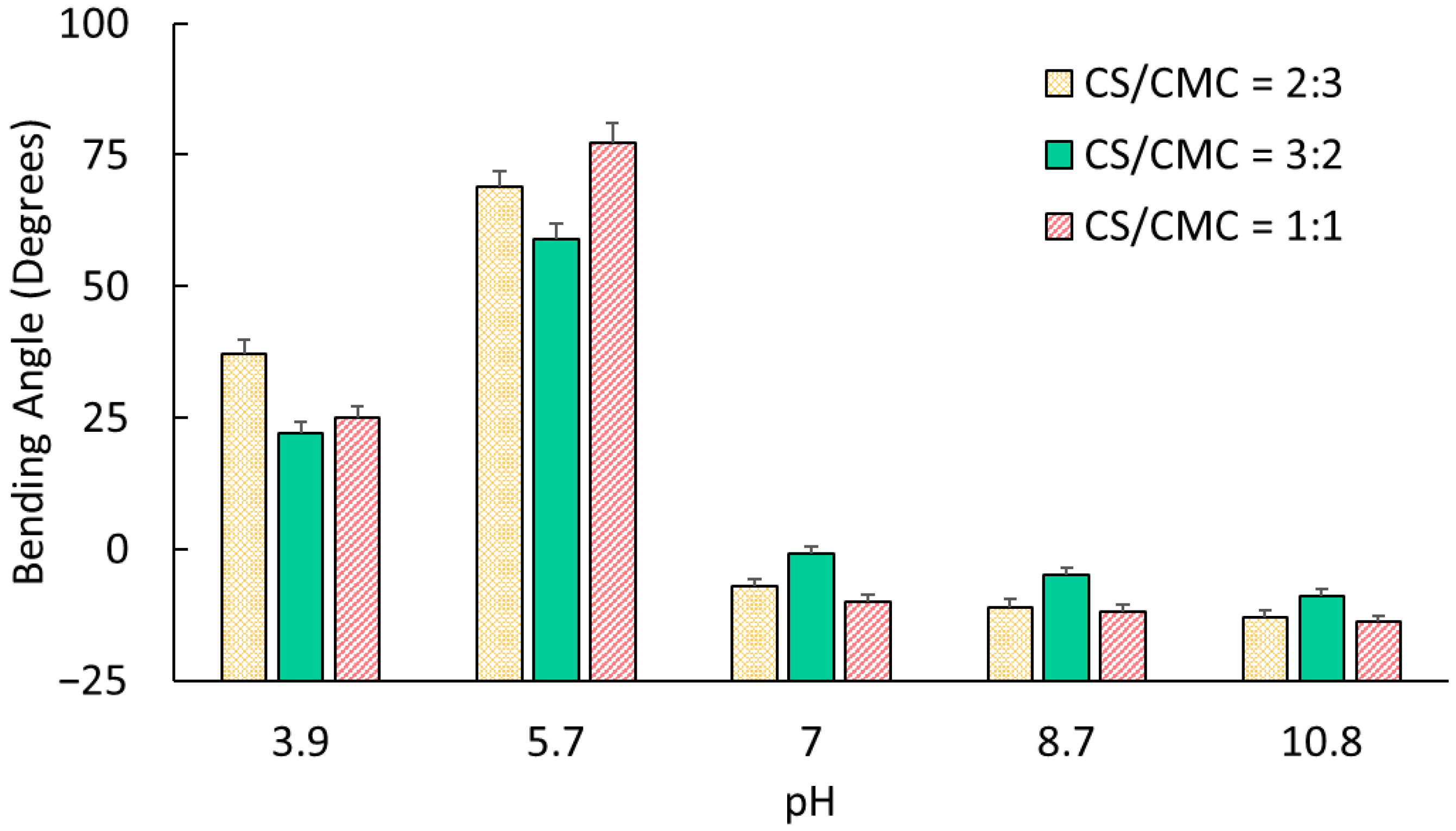

The electromechanical bending of polyelectrolyte hydrogels results from asymmetric counterion migration within the gel matrix under the applied electric field [

30]. For polyanionic networks, mobile counterions migrate toward the cathode, creating ionic concentration gradients across the hydrogel thickness. This generates differential osmotic pressure, with higher pressure developing near the anode compared to the cathode-facing surface of the domain, inducing bending toward the cathode. This mechanism reverses in polycationic networks, where counterion migration leads to anode-directed bending [

26].

The pH-dependent bending behavior of CS/CMC hydrogels directly correlates with their dominant ionic characteristics. In this study, when NH3+ concentration exceeded that of COO− (pH 3.9–5.7), the hydrogels exhibited polycationic behavior with anode-directed bending, reaching maximum angles of 37° (CS/CMC = 2:3 at pH 3.9) and 77° (CS/CMC = 1:1 at pH ≈ 5.7). As COO− predominated in solutions with pH > 7.0, networks became polyanionic, exhibiting cathode-directed bending with angles ranging from −1° to −14°.

The findings suggest that the CS/CMC ratio significantly influences the electromechanical response through modulation of charge density and network structure. To support this hypothesis, we note that gels with CS/CMC = 1:1 demonstrated superior performance at pH ≈ 5.7, achieving the highest bending angle (77°). This optimal performance could be because of the balanced electrostatic interaction between the NH

3+ and COO

− groups, creating maximal charge density at minimal swelling conditions [

33].

At pH ≈ 3.9, despite the lower NH

3+ content compared to other compositions, samples with CS/CMC = 2:3 exhibited the highest bending angle (37°). This apparent contradiction could be explained by their lower swelling ratio (4.67), which resulted in higher effective charge density and enhanced electromechanical coupling. The relationship between the swelling and bending performance suggests that the relative charge density, rather than absolute charge quantity, determines the electromechanical response of these hydrogels [

22,

34].

Under basic conditions (pH > 7.0), the gels with CS/CMC ratios of 2:3 and 1:1, which had higher CMC content, showed enhanced cathodic bending due to their large COO

− concentration. Interestingly, the absolute bending angles in the basic media (−1° to −14°) remained substantially lower than in acidic conditions (22° to 77°) [

22,

35]. This observation is consistent with previous studies and likely results from stronger hydrogen bonding between chitosan chains in basic solutions that restricted mechanical deformation [

22].

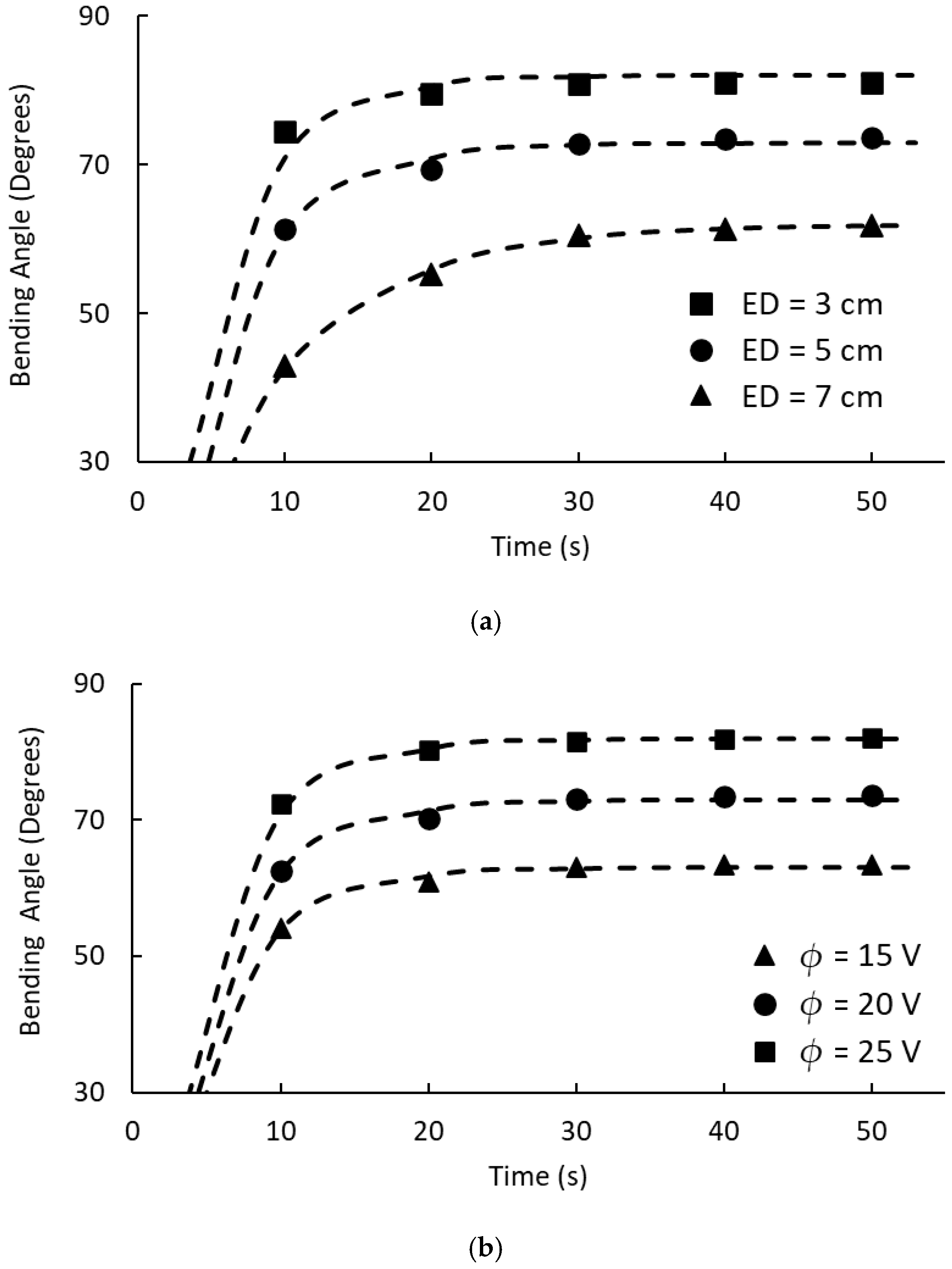

The electrode distance significantly affected the bending performance through its inverse relationship with the electric field intensity. Reducing the electrode distance from 7 cm to 3 cm increased the equilibrium bending angle from 62° to 81° at 50 s. This enhancement resulted from increased current density between electrodes [

36], which strengthened the electric field and accelerated ion migration processes. The data showed consistent improvements across all time points, with the most dramatic enhancement observed during the initial response (10 s), where bending increased from 43° to 74°, with decreased electrode distance.

The applied voltage demonstrated similar performance enhancement, such that increasing the electric voltage from 15 V to 25 V yielded equilibrium bending angle improvements from 63° to 82°. Higher voltages accelerated counterion transport rates [

22,

24,

37], facilitating faster development of osmotic pressure differentials across the hydrogel. Our previous research demonstrated that voltage increases resulted in more rapid establishment of these pressure gradients at the hydrogel–solution interface [

38,

39].

The temporal evolution of bending angles revealed biphasic behavior: rapid initial response within 10 s, followed by a gradual approach to equilibrium over 50 s. This pattern reflects the initial rapid counterion redistribution phase followed by slower polymer chain reorganization and structural equilibration, consistent with established electroactive polymer kinetics.

The present investigation focused on a single set of hydrogel strip dimensions without systematic exploration of geometric effects on bending performance, which may reduce the extent to which the quantitative conclusions can be generalized. Furthermore, the measurements in this work were conducted under steady-state conditions, with unidirectional electric field application. Thus, we could not fully capture the dynamic behavior and reversibility characteristics that might be essential for practical actuator applications. We expect that computational simulations based on chemo–electro–mechanical models provide the necessary insight on the role of mechanical properties, current distribution, and ion transport kinetics in the electroactive response of CS/CMC hydrogels [

39,

40].

5. Conclusions

This investigation constructed electroactive CS/CMC hydrogels with enhanced electromechanical properties through systematic manipulation of polymer composition ratios and operating parameters. We demonstrated control over their bending behavior by varying CS/CMC volume ratios. In particular, gels with CS/CMC = 1:1 exhibited significant bending (77°) at pH ≈ 5.7, and those with CS/CMC = 2:3 showed large bending response (37°) at pH ≈ 3.9. All compositions displayed robust pH-dependent bidirectional bending, with positive angles (22–77°) in acidic conditions and negative angles (−1 to −13°) in basic environments, confirming successful development of amphoteric electroactive networks.

Operating parameters significantly influenced the actuation performance, with electrode distance reduction from ED = 7 cm to ED = 3 cm, enhancing bending angles by approximately 30% (70° to 81° at 50 s), and voltage increases from 15 V to 25 V, improving response by 30% (63° to 82°). The established correlation between swelling behavior, composition, and bending performance provides valuable design principles for optimizing electroactive hydrogels, demonstrating that the relative charge density rather than absolute charge quantity determines actuation efficiency.

The biodegradable biocompatible CS/CMC hydrogels offer promising alternatives to synthetic electroactive polymers for applications, including drug delivery systems, soft robotics, and biomimetic artificial muscles, where biocompatibility is paramount. While this study explored the relationship between CS/CMC composition, pH, and electromechanical performance, several important areas warrant future investigation to advance practical actuator development. Systematic studies examining the effects of hydrogel dimensions provide the essential information required for assessing scalability. Furthermore, investigating the effects of temperature helps in the development of operating guidelines for biomedical applications. Finally, real-time polarity reversal experiments are needed to evaluate the reversibility and durability of these hydrogels under dynamic operating conditions.