Abstract

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor that arises from smooth muscle cells, accounting for less than 3% of all cutaneous sarcomas. Our case report details a 63-year-old male patient who presented with a rapidly growing, painful nodule in the popliteal region. The patient underwent initial surgical excision in September 2021, followed by three subsequent resections until March 2022 due to local recurrence. Histopathological analysis of all specimens revealed a dermal neoplasm composed of spindle cells arranged in intersecting fascicles with storiform patterns. The immunohistochemistry profile showed strong positivity for the markers SMA and desmin, confirming the diagnosis. Despite early interventions, the deep surgical margins were positive, and further surgeries were required until tumor-free margins were achieved. This case emphasizes the morphological characteristics, clinical behavior, and therapeutic challenges in managing cutaneous leiomyosarcoma. A favorable prognosis is achieved with long-term follow-up and a multidisciplinary approach.

1. Introduction

Cutaneous sarcomas are rare malignant neoplasms characterized by unique clinical and histopathological features. They predominantly affect the head and neck region, although they can also be found in other areas of the body. The most frequently encountered entities in this group include dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS), and atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), each of which has distinct clinical behavior and treatment considerations. The prognosis is variable, but DFSP patients generally have the best outcomes, despite the high recurrence rate [1,2].

Leiomyosarcomas (LMSs) are malignant tumors that originate from smooth muscle cells. These tumors are known for their aggressive behavior and can arise in various anatomical locations, including the retroperitoneum, trunk, abdomen, and extremities. When leiomyosarcomas develop in the skin, they are classified as cutaneous leiomyosarcomas, representing a very rare subset that accounts for less than 3% of all skin sarcomas. The prognosis of cutaneous entities is better compared to their visceral counterparts [1,2,3,4,5].

The diagnosis of these tumors relies on complete surgical excision followed by histopathological analysis. In addition to routine microscopic examinations, evaluating key parameters such as the depth of invasion, degree of differentiation, and mitotic count is essential for determining the prognosis and guiding therapeutic decisions. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) further enhances diagnostic accuracy by providing information regarding specific markers that confirm the tumor’s smooth muscle origin, thereby distinguishing leiomyosarcomas from other skin sarcomas [1,4,5,6,7].

Understanding the clinical and pathological features of cutaneous LMS and continuing research on the topic are essential for developing new approaches in these cases, which may provide patients with a better outcome.

2. Case Report

We present the case of a 63-year-old male patient who was admitted to the Surgery Department at Mureș Clinical County Hospital in September 2021 with a rapidly growing, painful mass in the right popliteal region. The mass was surgically removed, and the tissue sample was sent to the hospital’s Pathology Department for evaluation.

Two months later, in November 2021, the patient returned with a recurrent tumor in the exact anatomical location. Another surgical excision was performed, and the specimen was sent for analysis to the Pathology Department.

This pattern repeated in December 2021 and March 2022, with the patient experiencing similar symptoms and undergoing surgical removal each time. In all cases, tissue samples were sent to the Pathology Department for further examination, which will be detailed below.

The samples were processed using a routine histopathological technique. The specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and afterwards embedded in paraffin, followed by Hematoxylin-eosin staining. Immunohistochemistry reactions were performed on 4 μm-thick sections prepared from the parrafin blocks containing the fixed tissue. An automated immunostainer (Benchmark GX, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) was used and the markers were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were developed using a Diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) and were counterstained with Hematoxylin.

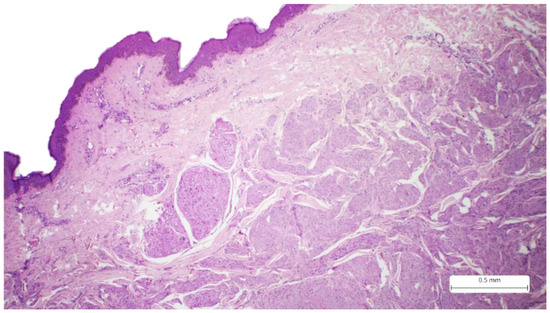

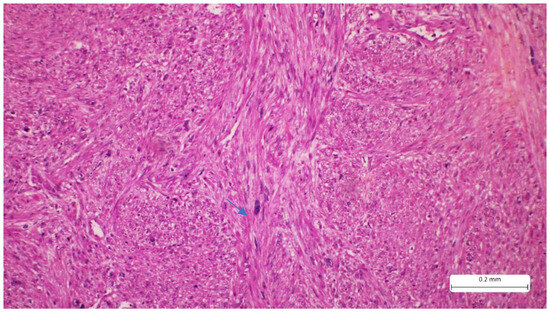

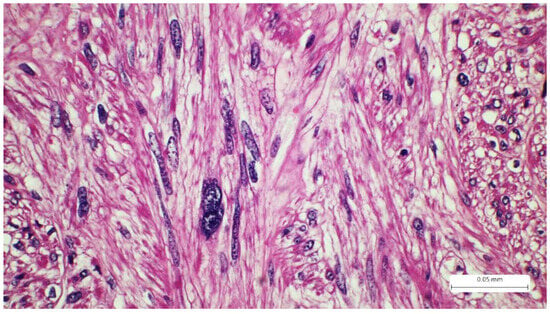

The initial excision (September 2021) consisted of a cutaneous sample measuring 36 × 10 mm, with a thickness of 25 mm, and presented a firm, white area of 30 × 9 × 24 mm on the cut section. Histological analysis using the usual Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed a solid tumor proliferation in the reticular dermis. The tumor was composed of fascicles of spindle cells with visible storiform areas (Figure 1). The tumor cells showed eosinophilic cytoplasm, elongated and enlarged nuclei with irregular borders, and a cigar-shaped appearance (Figure 2). Some cells exhibited high pleomorphism, with hyperchromatic and lobulated nuclei. (Figure 3). The mitotic index was 15/10 HPF. Necrosis and lymphatic or vascular invasion were not identified. The tumor infiltrated the deep surgical resection margin.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous sample covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which presents a tumor proliferation with an infiltrative pattern and irregular borders in the reticular dermis, Hematoxylin-eosin.

Figure 2.

Tumor proliferation consists of intersecting fascicles of atypical spindle cells separated by fine bundles of collagen. The tumor cells present eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated, hyperchromatic nuclei, with a cigar shape (arrow). A minimal inflammatory infiltrate can also be seen in the tumor stroma (Hematoxylin-eosin).

Figure 3.

Tumor spindle cells with highly pleomorphic nuclei, cigar-shape, Hematoxylin-eosin.

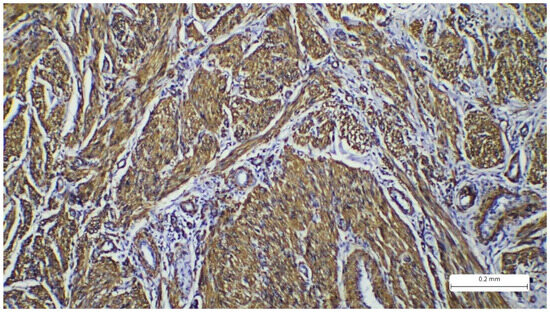

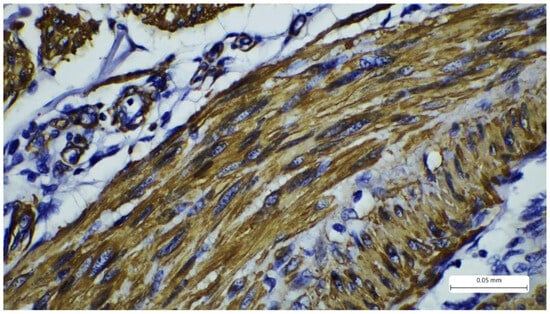

The immunohistochemistry profile showed strong positivity for SMA (Actin, smooth muscle (1A4), Mouse Monoclonal Antibody, CELL MARQUE) and desmin (CONFIRM anti-Desmin (DE-R-11) Primary Antibody, VENTANA). Markers S100 and CD68 were negative (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The Ki67 proliferation index was expressed in 30% of tumor cells. The morphological and immunohistochemical findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, grade I, according to the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) and FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer) grading systems. This grade is determined by the following parameters: differentiation, mitotic activity, and necrosis. For differentiation, the tumor receives a score from 1 to 3, where 1 represents sarcomas that resemble normal adult mesenchymal tissue, 2 represents sarcomas for which histologic type is certain, and 3 represents undifferentiated tumors. Mitotic activity scores from 1 to 3, where 1 is given for 0–9 mitoses/10 HPF, 2 for 10–19 mitoses/10 HPF, and 3 for more than 20 mitoses/10 HPF. Tumor necrosis scores range from 0 to 2, where 0 has no necrosis, 1 has less than 50% necrosis, and 2 presents with more than 50% necrosis. These scores are added to determine the grade. Our patient received 1 for differentiation, 2 for mitoses, and 0 for necrosis, totaling a score of 3, which places the case in the FNCLCC category G1 [8,9].

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry reaction with cytoplasmic marker SMA showing positivity in the tumor spindle cells.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry reaction with cytoplasmic marker desmin showing positivity in the tumor spindle cells.

The first re-excision (November 2021) involved a cutaneous sample measuring 65 × 25 mm, featuring a linear scar on its surface. The cut section revealed an irregular, firm, white area measuring 10 mm × 3 mm. Histological examination showed a fibrous scar with residual tumor proliferation in the reticular dermis. The tumor retained its solid architecture and spindle cell composition. The tumor cells presented eosinophilic cytoplasm, hyperchromatic, elongated nuclei with irregular borders, and high pleomorphism. The mitotic rate was 20 mitoses/10 HPF, yet without evidence of necrosis, lymphatic, or vascular invasion. The deep surgical margin was again infiltrated. Immunohistochemistry confirmed positivity for the marker SMA, leading to the diagnosis of recurrent cutaneous leiomyosarcoma.

The second re-excision (December 2021) involved a cutaneous sample measuring 120 × 25 mm, with an ulcerated area and a linear scar. A white nodule measuring 80 × 12 mm was noted on the cut section. Histological examination revealed a fibrous scar adjacent to a tumor proliferation with the same histological and immunohistochemical features as previously described. Once again, the deep surgical margin was infiltrated by the tumor.

The third re-excision (March 2022) involved a cutaneous sample measuring 90 × 38 mm, containing an indurated area measuring 35 × 5 mm. Microscopic examination confirmed the presence of recurrent leiomyosarcoma, presenting the same characteristics as the previous excisions. The resection margins were tumor-free, with tumor cells located at 4 mm from the marked margin.

The patient is under continuous oncological and surgical surveillance and has not presented with metastasis or recurrence ever since. Two check-ups were done for the first half a year after the last surgery, consisting of clinical examination, ultrasonography, and a CT scan. Other imagistic investigations were not performed. Ever since, the patient has presented for consultations; ultrasound and clinical assessments continued to be performed. The last follow-up known to have been conducted was in the first quarter of 2024.

3. Discussion

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is an uncommon malignant tumor. This is most seen in adults, with a slight predominance in males. The data aligns with our case, which involved a 63-year-old male patient. The literature reports various cases in female patients as well and emphasizes the differences in outcomes based on gender distribution. Some studies focused on analyzing the particularities of primary LMS in large cohorts of patients and demonstrated that women experienced a worse prognosis (Kaplan–Meier curve exhibiting poor survival in female gender, this being an independent prognostic factor) [10,11,12].

Although cutaneous LMS represents a small subset of soft tissue sarcomas, it is distinct from subcutaneous and visceral leiomyosarcomas in behavior and prognosis. Cutaneous forms typically originate from arrector pili muscles or dermal vasculature, which may contribute to their more indolent course compared to deeper counterparts [5]. Most primary cutaneous LMSs have been described as appearing on the limbs; however, some studies contradict this data. There is also information regarding the location variations based on gender, as female patients tend to develop these tumors in the head and neck area and the trunk. Male patients also present variations in the location, trunk, dorsal region, and extremities, which are described most often. The most affected areas of the limbs are the thigh and, particularly, the calf. Our patient is part of the last category, as he presented with a tumor in the popliteal region [12,13].

The clinical appearance of LMS typically consists of a nodular mass that grows rapidly, often without presenting symptoms. Sometimes, patients describe tenderness or ulcerations. Our patient experienced rapid tumor growth over a couple of months, along with pain [5,12,13].

Microscopic examination of the tumor samples provides crucial data for the patient’s prognosis. On the HE stains, we can observe details regarding the tumor’s architecture and cytology. Typically, LMS presents solid proliferation, with tumor cells arranged in fascicles with storiform patterns. The cells are spindle-shaped, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated nuclei that have a cigar-shaped appearance. Pleomorphism and atypia are evident, and the mitotic count is commonly high [1,14]. Despite these characteristics, HE staining alone is insufficient for diagnosis, as LMS can exhibit variability in these features and resemble other sarcomas with similar patterns (for example, tumors of neural or melanocytic origin). Thus, confirmation of the diagnosis is required, and immunohistochemistry is performed. Markers such as SMA (smooth muscle actin), desmin, and caldesmon are used to determine the myogenic origin. The tumor should be positive for at least two of these markers. Our case showed positivity for SMA and desmin. Caldesmon was not performed due to limited availability in our laboratory. Additionally, the Ki-67 proliferation index was expressed in 30% of the tumor cells. Neural origin (malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor) and melanocytic origin (spindle cell melanoma) were excluded based on IHC, not only due to positivity for myogenic markers but also due to negativity for S100. For spindle cell melanoma, markers like PRAME and SOX10 would exhibit higher specificity, but S100 is highly sensitive for melanocytic lineage. Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), a key differential diagnosis of LMS, was also excluded because the CD68 marker was negative. AFX also presents additional details such as the presence of epithelioid or multinucleated cells, which were absent in our case. Other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), also enter the differential diagnosis. However, this neoplasm typically exhibits a storiform pattern with invasion of the hypodermis, a classic aspect known as “honeycomb”, a feature which is absent in the usual stain in our case. In addition, the mitotic index is low, and the tumor exhibits CD34 positivity. The CD34 marker is essential for DFSP diagnosis and differential diagnoses with storiform tumors, and its positivity excludes LMS [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Another important differential diagnosis is cutaneous leiomyoma, the benign counterpart of LMS. This tumor originates in the arrector pili muscle or in the smooth muscle of the blood vessels. It can present as multiple lesions (associated with Reed syndrome) or solitary lesions with increased consistency. The tumor is composed of spindle cells with elongated nuclei, arranged in intersecting fascicles. It is well-defined, lacks a capsule, atypia is absent, and the mitotic count is low. Like LMS, the tumor is positive for myogenic markers, including SMA, desmin, and caldesmon, while the proliferation index, Ki-67, is low, with a value of less than 5%. Surgery is curative, but follow-up is required, especially in cases where multiple leiomyomas are encountered [1,21,22]. As mentioned before, Reed syndrome is one of the diseases that leads to numerous leiomyoma growths. This is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the presence of uterine and cutaneous leiomyomas [23]. Another syndrome where leiomyomas are encountered is hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, also an autosomal dominant disorder with only a few cases reported so far. Yet, cutaneous involvement in this pathology is rare, and most patients present with uterine leiomyomas associated with renal cancer [24].

Kaposi sarcoma is a rare disease with intermediate behavior and pathogenesis associated with HHV8 (Human Herpes Virus 8) infection, as well as genetic mutations. The tumor is represented by cutaneous vascular proliferation, and it is encountered in Mediterranean areas, in endemic regions (in African populations), in patients with immunodeficiency (HIV infection), or can occur iatrogenically [25]. The histological aspects include various stages, including the nodular stage, which can be a prominent differential diagnosis of LMS. Here, the tumor consists of intersecting fascicles made of uniform spindle cells. Between the cells, blood vessel formation and blood-filled spaces (slit-like or sieve-like) can be observed. Pleomorphism is low or absent, and mitoses are common. The tumor is positive for markers CD34, ERG, CD31, D2-40, and HHV8 and negative for myogenic markers [26,27].

LMS is an aggressive neoplasm overall. The cutaneous variant has a prognosis that depends significantly on the metastatic potential of the tumor. This parameter is influenced by the size of the tumor and the vascular invasion. The deeper the tumor thickness is, the greater the metastatic risk. Commonly, cutaneous LMS secondarily involves distant cutaneous areas, and the internal organs are not frequently affected. However, metastatic cases increase the mortality risk in such patients [28]. Essential and effective therapeutic options include wide excisions with large resection margins and Mohs surgery. The latter is a surgical technique developed to provide adequate resection of malignant tumors, especially for the head and neck region. It has been used in a large variety of cancers with great success, and it is the gold standard for skin neoplasms. The technique involves mapping of the tumor and layer-by-layer removal. This is made by combining surgery with fast histological examination of an ”en face” sample (the cut is made in a horizontal plane). The resection continues until the sample is clear of tumor cells [29,30,31]. In our case, surgical excision was a challenge. Wide local excision has been performed. The first three resections presented tumor-infiltrated margins. For the last one, free margins were obtained, 4 mm distance from the closest tumor cell. Guidelines recommend a minimum of 5–10 mm margins. Considering the low grade of the tumor and multiple resections already performed, surveillance was opted for. The patient has shown no metastasis or recurrence to date, as confirmed by the last follow-up in the first quarter of 2024.

This data is essential, as LMS has an excellent survival rate if the tumor is completely removed (approximately 90% at 5 years). In cases where proper removal is not possible, adjuvant therapies may be considered (such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy), but these cases are rare. Our patient did not benefit from any adjuvant treatment. It is also important to note that outcomes may vary significantly from patient to patient, as data regarding cutaneous LMS is limited due to the low number of cases reported to date. Limitations of this case include the absence of molecular characterization and the relatively short follow-up interval, which limits conclusions about long-term outcomes [31,32].

4. Conclusions

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare, aggressive malignancy with smooth muscle origin. The diagnosis relies on histopathological analysis and identification of the tumor’s IHC profile. This case report describes important histological and cytological features of primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, along with its differential diagnoses. Additionally, it highlights the challenges of surgical management in achieving tumor-free resection margins, which is extremely important for the patient’s outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to this case report involving a single patient, and did not constitute a study requiring ethics committee or IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No data was created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LMS | Leiomyosarcoma |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| FNCLCC | Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer |

References

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3, Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/588 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Skin Tumours [Beta Version Ahead of Print], 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2023; Volume 12, Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/64 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Soares Queirós, C.; Filipe, P.; Soares de Almeida, L. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: A 20-year retrospective study and review of the literature. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2021, 96, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbig, D.; Dippel, E.; Erdmann, M.; Frisman, A.; Kage, P.; Leiter, U.; Mentzel, T.; Seidel, C.; Weishaupt, C.; Ugurel-Schmidt, S. S1-guideline cutaneous and subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2023, 21, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deneve, J.L.; Messina, J.L.; Bui, M.M.; Marzban, S.S.; Letson, G.D.; Cheong, D.; Gonzalez, R.J.; Sondak, V.K.; Zager, J.S. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: Treatment and outcomes with a standardized margin of resection. Cancer Control. 2013, 20, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, G.N.; Webb, A.; Gyorki, D.; McCormack, C.; Tran, P.; Ngan, S.Y.; Slavin, J.; Henderson, M.A. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: Dermal and subcutaneous. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2020, 61, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfant, V.; Schriber, T.; Sabri, A.; Gossen, J.; Groh, D. Primary Cutaneous Leiomyosarcoma of the Lower Extremity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e14282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, B.N.; Liu, J.C. Cutaneous Sarcomas. Otolaryngol. Clin. North. Am. 2021, 54, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, N.; Sauvageau, A.P.; Groman, A.; Bogner, P.N. Cutaneous Leiomyosarcoma: A SEER Database Analysis. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.A.; Thomas, S.; Ituarte, B.; Sharma, D.; Georgesen, C.; Wei, E.X.; Voss, V. Sex disparities in leiomyosarcoma of the skin: Females experience worse disease-specific survival. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Asher, R.; Perkins, W.; Matin, R.N. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: A retrospective review of 45 cases. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 49, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, V.; Cope, B.; Keung, E.Z.; Fiore, M. Management of Skin Sarcomas. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 31, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walocko, F.; Christensen, R.E.; Worley, B.; Alam, M. Cutaneous Mesenchymal Sarcomas. Dermatol. Clin. 2023, 41, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Company-Quiroga, J.; Magro-García, H.C.; Martínez-Morán, C. Spindle-cell malignant melanoma. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2020, 86, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrycaj, S.M.; Szczepanski, J.M.; Zhao, L.; Siddiqui, J.; Thomas, D.G.; Lucas, D.R.; Patel, R.M.; Harms, P.W.; Bresler, S.C.; Chan, M.P. PRAME expression in spindle cell melanoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, and other cutaneous sarcomatoid neoplasms: A comparative analysis. Histopathology 2022, 81, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.H.; Haidar, Y.M. Malignant Peripheral Nerve-Sheath Tumor. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somatilaka, B.N.; Sadek, A.; McKay, R.M.; Le, L.Q. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: Models, biology, and translation. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2405–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaimy, A. The many faces of Atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 40, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, N.V.; Vtorushin, S.V.; Maltseva, A.A.; Sannikova, A.V. Atipicheskaya fibroksantoma [Atypical fibroxanthoma]. Arkh. Patol. 2023, 85, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernett, C.N.; Mammino, J.J. Cutaneous Leiomyomas. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, K.; Patel, P.; Chen, J.; Khachemoune, A. Leiomyoma cutis: A focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2015, 16, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Saxena, S.; Singh, S.; Malhotra, P. Reed Syndrome: A Varied Presentation. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 12, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, F.; Guan, B.; Shen, Q.; Yang, F.; He, Q.; Li, X. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): Case series and review of the literature. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 39, 791.e9–791.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batash, R.; Crimí, A.; Kassem, R.; Asali, M.; Ostfeld, I.; Biz, C.; Ruggieri, P.; Schaffer, M. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: Diagnostics, treatment modalities, and genetic implications—A review of the literature. Acta Oncol. 2024, 63, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Alanís, J.C.; Salas-Garza, M.; Moreno-Treviño, M.G.; Márquez-Murillo, S.; Rivera-Silva, G. Kaposi’s sarcoma. Med. Clin. 2025, 164, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoureux, C.; Drak Alsibai, K.; Pradinaud, R.; Sainte-Marie, D.; Couppie, P.; Blaizot, R. Kaposi Sarcoma with Mucocutaneous Involvement in French Guiana: An Epidemiological Study between 1969 and 2019. Acta Derm Venereol 2022, 102, adv00709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winchester, D.S.; Hocker, T.L.; Brewer, J.D.; Baum, C.L.; Hochwalt, P.C.; Arpey, C.J.; Otley, C.C.; Roenigk, R.K. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: Clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golda, N.; Hruza, G. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Dermatol. Clin. 2023, 41, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkorn, J.R.; Alam, M. What Is Mohs Surgery? JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mora, P.; Llombart, B.; Castro, J.R.; Cruz, J.; Serra, C.; Requena, C.; Traves, V.; Sanmartín, O. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: A single institution study treated with modified Mohs surgery. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, e10–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzato, G.; Sergi, M.C.; Sablone, S.; Colagrande, A.; Lettini, T.; Fanelli, F.; Orsini, U.; Ingravallo, G. Advanced Cutaneous Leiomyosarcoma of the Forearm. Dermatopathology 2021, 8, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).