First Recorded Evidence of Invasive Rodent Predation on a Critically Endangered Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) Nestling in the Galápagos Islands

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

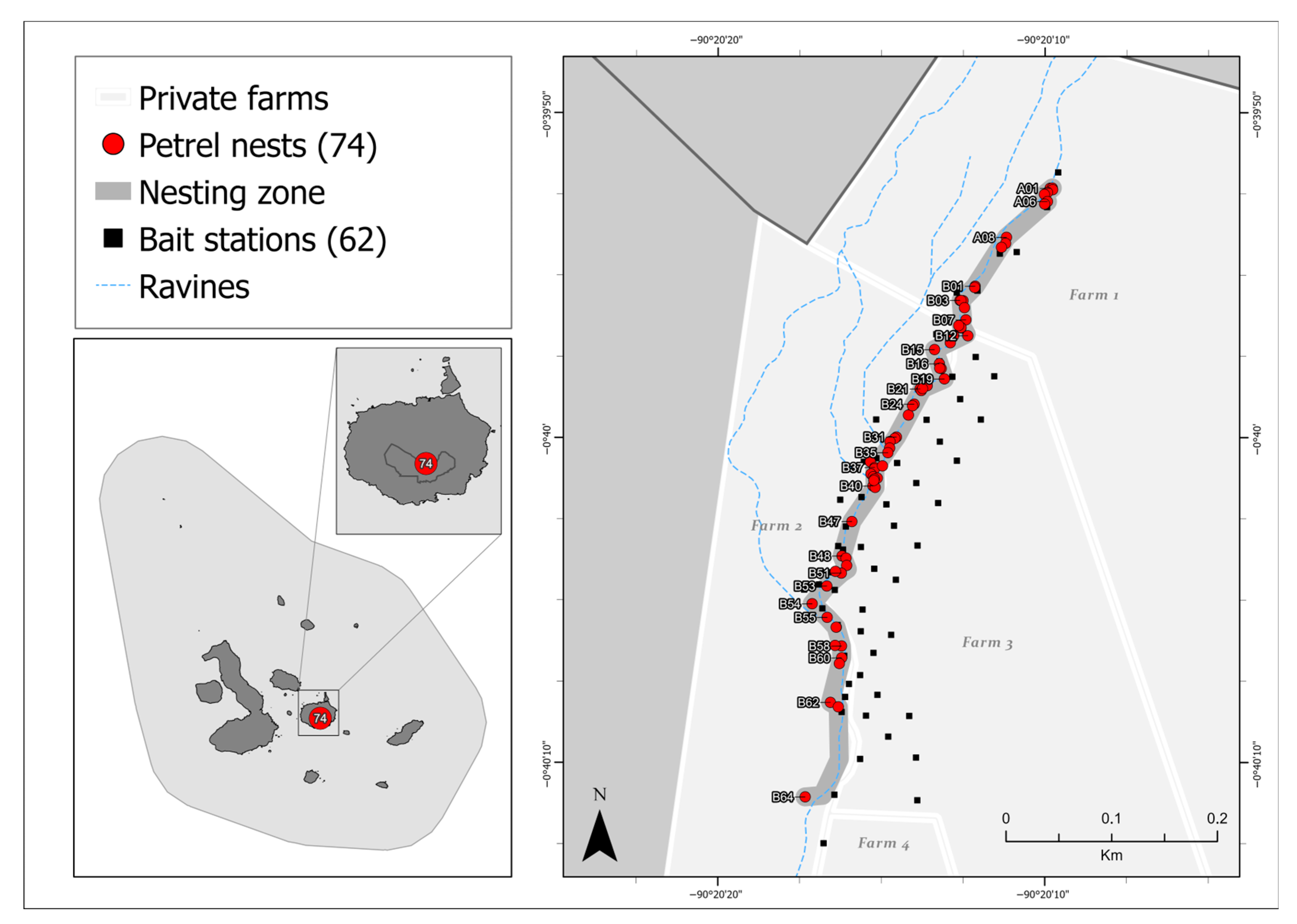

2. Methods

3. Results

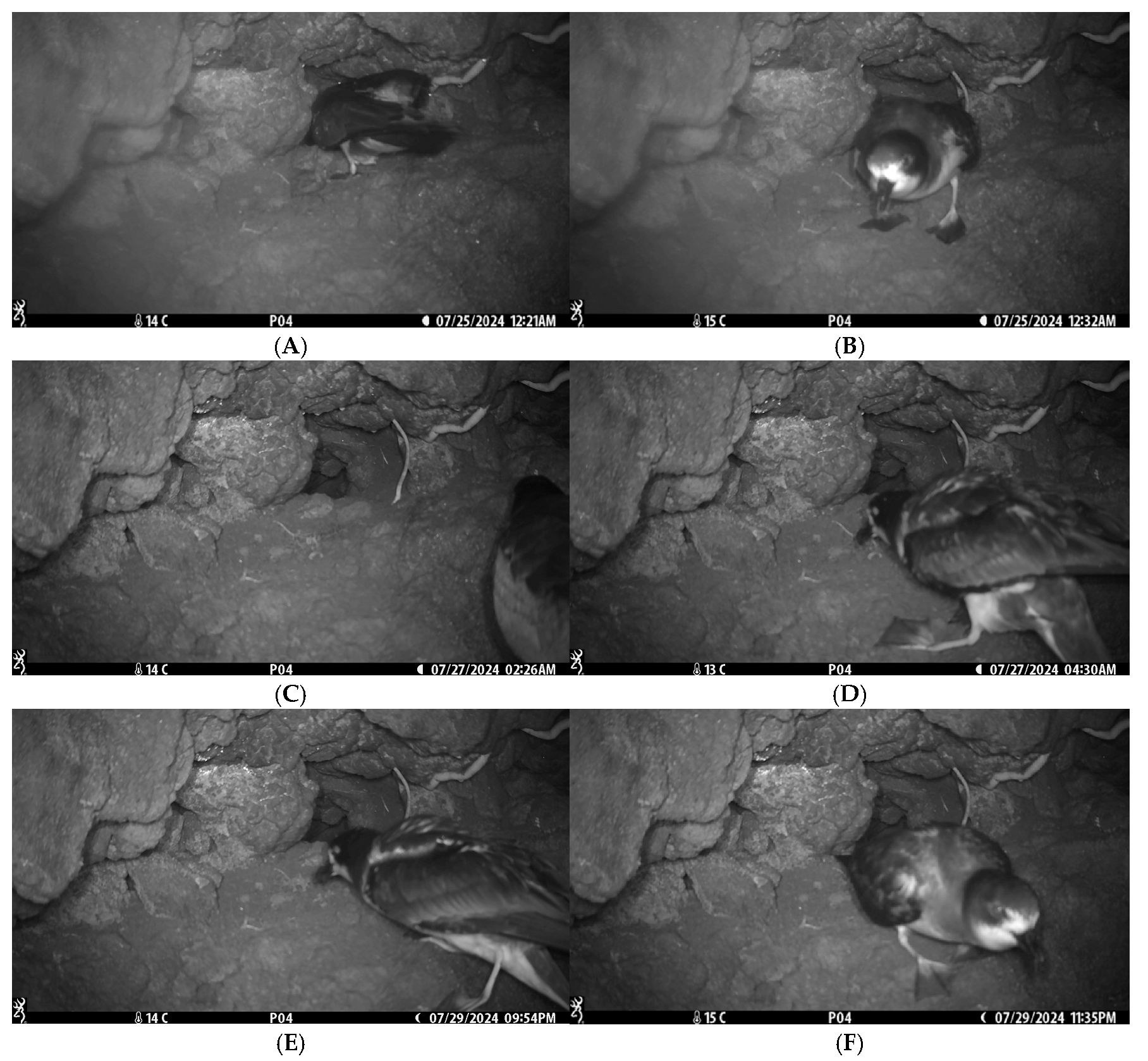

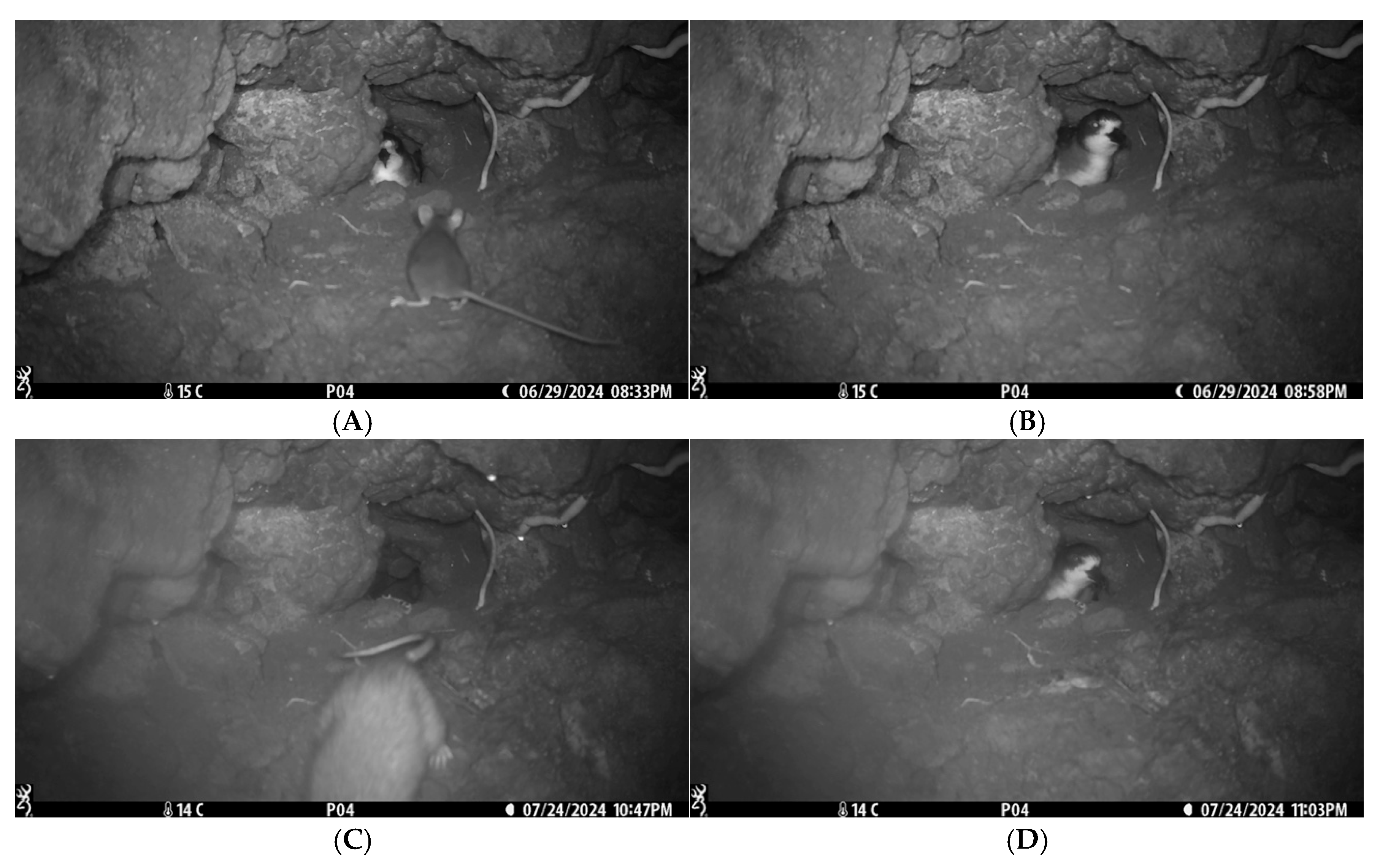

3.1. Initial Approaches and Parental Defense

3.2. Parental Absence and Nest Vulnerability

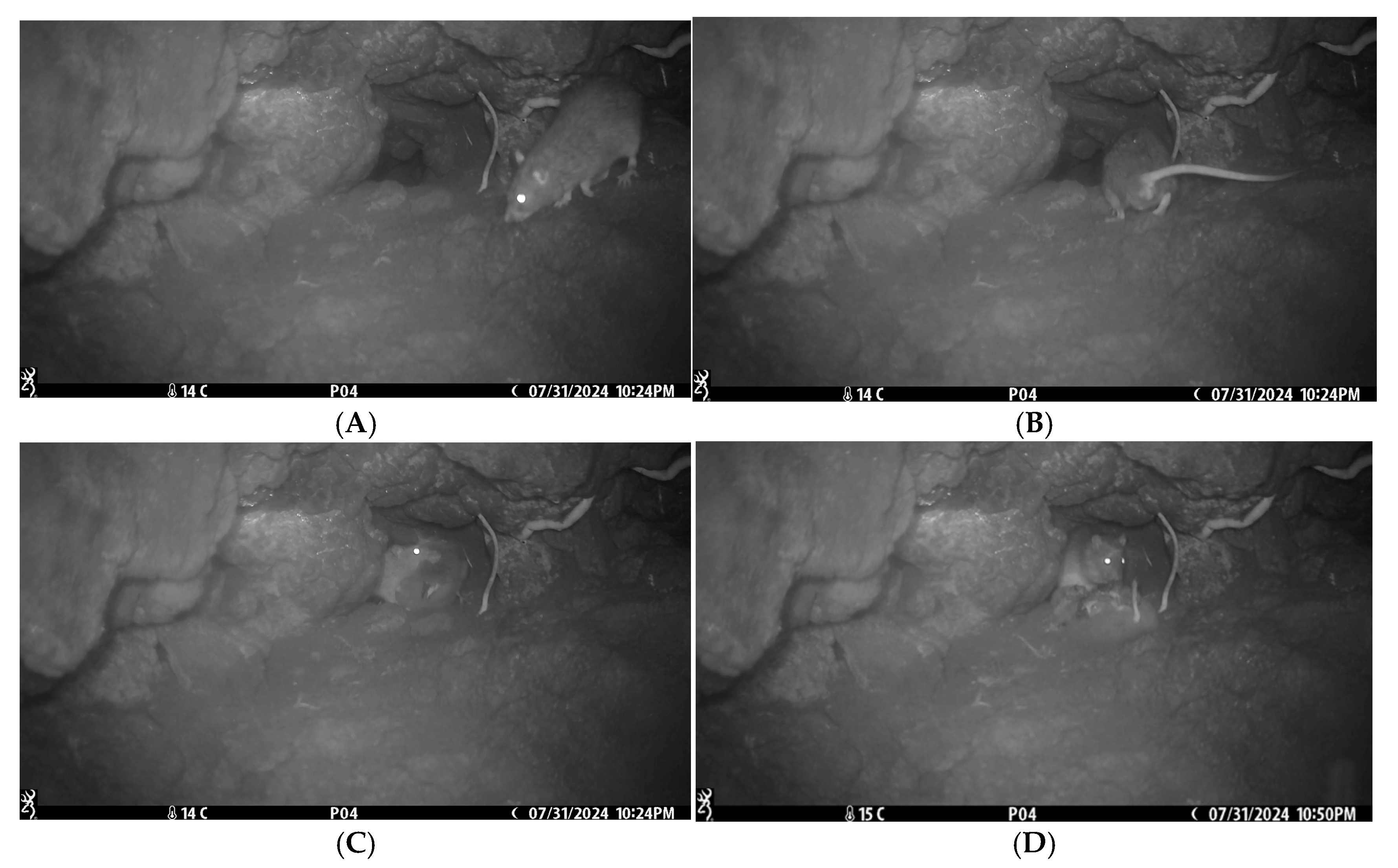

3.3. Predation Event

3.4. Parental Return and Nest Fidelity

4. Discussion

Key Conservation Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friesen, V.L.; González, J.A.; Cruz-Delgado, F. Population Genetic Structure and Conservation of the Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma Phaeopygia). Conserv. Genet. 2006, 7, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International Pterodroma phaeopygia, Galapagos Petrel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22698020/132619647 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Cruz-Delgado, F.; González, J.A.; Wiedenfeld, D.A. Breeding Biology of the Critically Endangered Galapagos Petrel Pterodroma Phaeopygia on San Cristóbal Island: Conservation and Management Implications. Bird Conserv. Int. 2010, 20, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proaño, C.; Cruz, S.; Zurita, L.; Nevins, H. Galapagos Petrel (Pterodroma Phaeopigya) Conservation Action Plan; Puerto Ayora: Santa Cruz, Ecuador, 2019; Available online: https://acap.aq/fr/actualites/dernieres-nouvelles/plans-are-afoot-to-help-conshttps-www-acap-aq-administrator-index-php-option-com-content-task-article-edit-id-4922erve-the-critically-endangered-galapagos-petrel (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ahassi, C. Lo Galapagueño, Los Galapagueños: Proceso de Construcción de Identidades En Las Islas Galápagos. Rev. Antropol. Exp. 2007, 169–176. Available online: https://revistaselectronicas.ujaen.es/index.php/rae/article/view/2033 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Moreno, S.H. Diseño de Un Producto Turístico Comunitario Sostenible Para La Isla Floreana, Provincia de Galápagos; Universidad de las Américas: Quito, Ecuador, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Uzcátegui, G.; Cruz-Delgado, F.; Proaño, C.B.; Sevilla, C.; Tapia, W.; Cruz, S.; Espinoza, E.; Samaniego, J.; Naranjo, S.; Zambrano, N. Ficha Técnica Del Petrel de Galápagos Pterodroma Phaeopygia; Incorporación de Una Nueva Especie al Apéndice I Del ACAP; Petrel de Galápagos Pterodroma Phaeopygia: La Rochelle, Francia, 2013; Available online: https://www.acap.aq/advisory-committee/ac7/ac7-meeting-documents/1999-ac7-doc-25-addition-of-a-new-species-to-annex-i-of-acap-the-galapagos-petrel-pterodroma-phaeopygia/file (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Cruz, J.B.; Cruz, F. Conservation of the Dark-Rumped Petrel Pterodroma Phaeopygia of the Galápagos Islands, 1982–1991. Bird Conserv. Int. 1996, 6, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenfeld, D.; Jiménez-Uzcátegui, G. Critical Problems for Bird Conservation in the Galápagos Islands. Cotinga 2008, 29, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alava, J.J.; Haase, B. Waterbird Biodiversity and Conservation Threats in coastal Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands. In Ecosystems Biodiversity; Grillo, O., Venora, G., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 271–314. ISBN 9789533074177. [Google Scholar]

- Croxall, J.P.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Lascelles, B.; Stattersfield, A.J.; Sullivan, B.; Symes, A.; Taylor, P. Seabird Conservation Status, Threats and Priority Actions: A Global Assessment. Bird Conserv. Int. 2012, 22, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.B.; Wiedenfeld, D.A.; Snell, H.L. Current Status of Alien Vertebrates in the Galápagos Islands: Invasion History, Distribution, and Potential Impacts. Biol. Invasions 2012, 14, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arica, J. (Jocotoco Conservation Foundation, Puerto Ayora, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador). Personal Communication, 2025.

- Sevilla, C. (Galápagos National Park Directorate, Puerto Ayora, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador). Personal Communication, 2025.

- Zurita-Arthos, L.; Proaño, C.; Guillén, J.; Cruz, S.; Wiedenfeld, D. Galapagos Petrels Conservation Helps Transition Towards a Sustainable Future. In Island Ecosystems; Walsh, S., Mena, C., Stewart, J., Muñoz-Pérez, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, R. Breeding Success and Mortality of Dark-Rumped Petrels in the Galapagos, and Control of Their Predators. In Conservation of Island Birds; Moors, P.J., Ed.; International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP Technical Publication no. 3): Cambridge, UK, 1985; pp. 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, J.B.; Cruz, F. Conservation of the Dark-Rumped Petrel Pterodroma Phaeopygia in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Biol. Conserv. 1987, 42, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riofrío-Lazo, M.; Páez-Rosas, D. Feeding Habits of Introduced Black Rats, Rattus Rattus, in Nesting Colonies of Galapagos Petrel on San Cristóbal Island, Galapagos. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.A. Foraging Patterns of Black Rats across a Desert-Montane Forest Gradient in the Galápagos Islands. Biotropica 1981, 13, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.A. Foraging Behavior of a Vertebrate Omnivore (Rattus Rattus): Meal Structure, Sampling, and Diet Breadth. Ecology 1982, 63, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.P.; Tershy, B.R.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Croll, D.A.; Keitt, B.S.; Finkelstein, M.E.; Howald, G.R. Severity of the Effects of Invasive Rats on Seabirds: A Global Review. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, W.A.; Collier, N.; Rolland, V. Non-Native Rats Detected on Uninhabited Southern Grenadine Islands with Seabird Colonies. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 4172–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.F.; Driskill, S.; Vynne, M.; Harvey, D.; Pias, K. Managing the Effects of Introduced Predators on Hawaiian Endangered Seabirds. J. Wildl. Manag. 2020, 84, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; Thibault, J.C.; Bretagnolle, V. Black Rats, Island Characteristics, and Colonial Nesting Birds in the Mediterranean: Consequences of an Ancient Introduction. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 1452–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.; Cruz, J.B. Breeding, Morphology, and Growth of the Endangered Dark-Rumped Petrel. Auk 1990, 107, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warham, J. The Petrels—Their Ecology and Breeding Systems; Academic Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, N.; Mitchell, I.; Varnham, K.; Verboven, N.; Higson, P. How to Prioritize Rat Management for the Benefit of Petrels: A Case Study of the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. Ibis 2009, 151, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Parent 1 Activity * (In/Out) | Parent 2 Activity (In/Out) | Nest Left Unattended (# Hours) | Rodent Visit (Time) | Observational Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Approaches | 29 June | In (entire day) | – | 0 h | 20:33 | The juvenile rat approached the nest and was immediately deterred by the attending parent. |

| 24 July | In (entire day) | 0 h | 22:47 | The adult rat approached the nest and retreated after detecting the parent. | ||

| Nest Vulnerability | 25 July | Out 00:32 | In (00:21–19:19) | 0 h | – | Both parents remained inside for 11 min before one departed to forage. Parent 2 left after 18 h and 47 min. |

| 26 July | In 02:31 | – | 7 h 12 min | – | ||

| 27 July | Out 02:26 | In 04:30 | 2 h 4 min | Parent 1 left after 23 h and 55 min. | ||

| 28 July | Out 03:21 | Parent 2 left after ~24 h. | ||||

| 29 July | In 21:54 Out 23:35 | – | 42 h 33 min | – | Brief return, then departure. | |

| Predation Event | 31 July | – | – | 46 h 49 min | 22:24 | The nestling was left unattended for the longest period. Nestling killed and removed by an adult rat. |

| Nest Fidelity | 2 August | In 04:43 Out 05:05 | – | 21:28 | Parent searched 22 min for nestling. An adult rat visited the nest and stayed for 2 min. | |

| 3 August | – | – | 01:55 | An adult rat visited the nest and stayed for 1 min. | ||

| 4 August | – | – | 21:19 | Adul rat visited the nest and stayed for 1 min. | ||

| 5 August | – | In 03:45 Out 04:23 | 70 h 40 min | 02:27 | The presumed second parent returned and searched the nestling for 38 min. | |

| 5 August–30 October | Periodic visits every~2 days | – | – | Nest inspections and vocalizations from visiting parents searching for the nestling. Frequent visits from rats were recorded. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tapia-Jaramillo, I.; Arica, J.; Espín, A.; Carrión, V.; Mayorga, J.P.; Sevilla, C.; Cruz, E.; Sangolquí, P. First Recorded Evidence of Invasive Rodent Predation on a Critically Endangered Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) Nestling in the Galápagos Islands. Birds 2025, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6030033

Tapia-Jaramillo I, Arica J, Espín A, Carrión V, Mayorga JP, Sevilla C, Cruz E, Sangolquí P. First Recorded Evidence of Invasive Rodent Predation on a Critically Endangered Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) Nestling in the Galápagos Islands. Birds. 2025; 6(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleTapia-Jaramillo, Isabela, Joel Arica, Alejandra Espín, Víctor Carrión, Juan Pablo Mayorga, Christian Sevilla, Eliécer Cruz, and Paola Sangolquí. 2025. "First Recorded Evidence of Invasive Rodent Predation on a Critically Endangered Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) Nestling in the Galápagos Islands" Birds 6, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6030033

APA StyleTapia-Jaramillo, I., Arica, J., Espín, A., Carrión, V., Mayorga, J. P., Sevilla, C., Cruz, E., & Sangolquí, P. (2025). First Recorded Evidence of Invasive Rodent Predation on a Critically Endangered Galápagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) Nestling in the Galápagos Islands. Birds, 6(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6030033