Unilateral to Bilateral Lumbosacral Plexopathy After Radiation Therapy: A Case Report

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

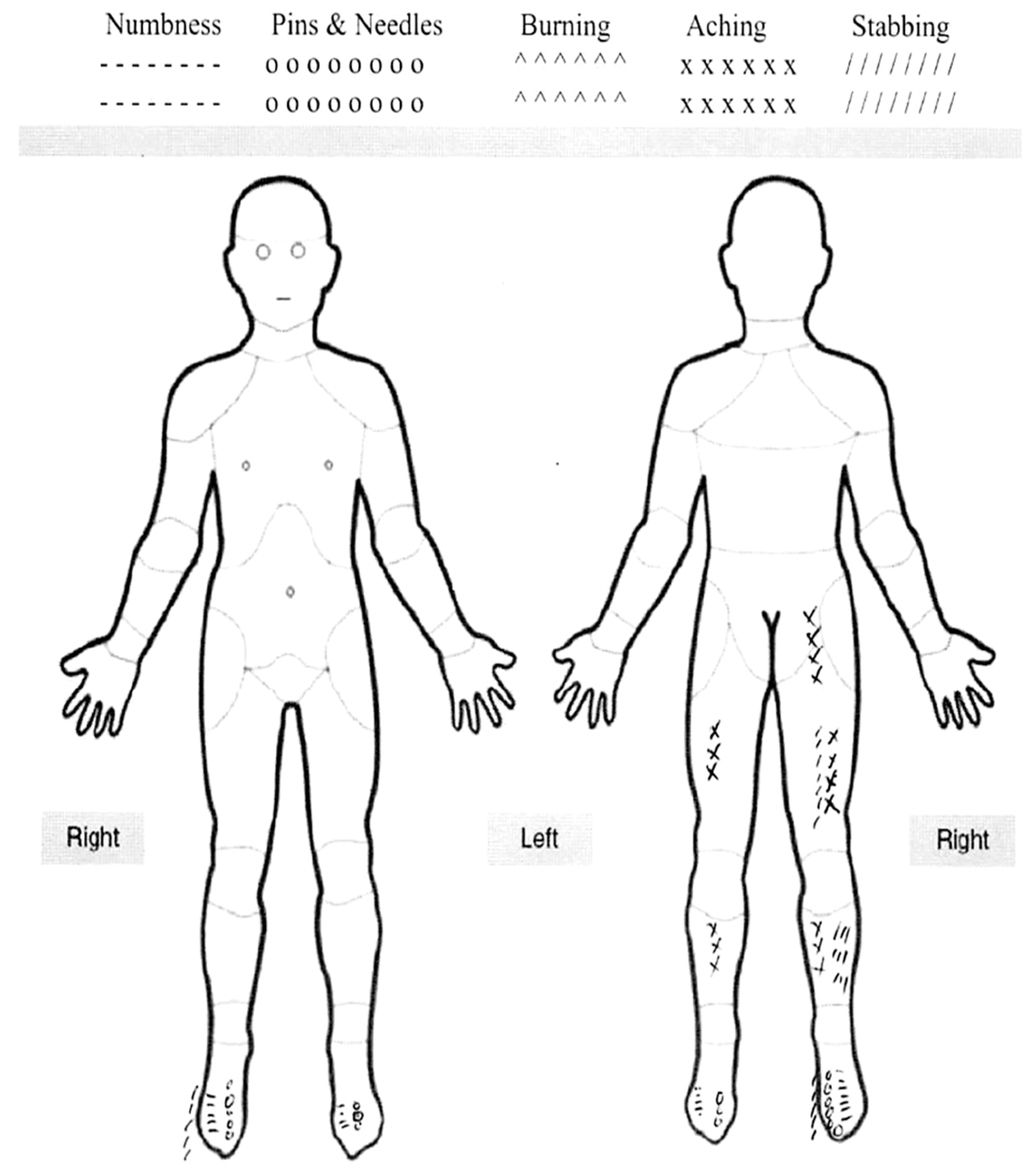

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tunio, M.; Al Asiri, M.; Bayoumi, Y.; Balbaid, A.A.O.; AlHameed, M.; Gabriela, S.L.; Ali, A.A.O. Lumbosacral plexus delineation, dose distribution, and its correlation with radiation-induced lumbosacral plexopathy in cervical cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, S.K.; Mak, W.; Yang, C.C.; Liu, T.; Cui, J.; Chen, A.M.; Purdy, J.A.; Monjazeb, A.M.; Do, L. Development of a standardized method for contouring the lumbosacral plexus: A preliminary dosimetric analysis of this organ at risk among 15 patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for lower gastrointestinal cancers and the incidence of radiation-induced lumbosacral plexopathy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 84, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delanian, S.; Lefaix, J.L.; Pradat, P.F. Radiation-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 105, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganswindt, U.; Paulsen, F.; Anastasiadis, A.G.; Stenzl, A.; Bamberg, M.; Belka, C. 70 Gy or more: Which dose for which prostate cancer? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 131, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Palmer, J.D.; Hurwitz, M.D.; Keith, S.W.; Dicker, A.P.; Den, R.B. What is the ideal radiotherapy dose to treat prostate cancer? A meta-analysis of biologically equivalent dose escalation. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 115, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robblee, J.; Katzberg, H. Distinguishing Radiculopathies from Mononeuropathies. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, L.R.; Faustino, D.; Esteves, L.R.; Gante, C.; Soares, A.W.; Oliveira, T.; Dias, J.L.; Dias, L. Radiation-Induced Lumbosacral Plexopathy. Cureus 2023, 15, e36842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahele, M.; Davey, P.; Reingold, S.; Shun Wong, C. Radiation-induced lumbo-sacral plexopathy (RILSP): An important enigma. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 18, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güler, T.; Yurdakul, F.G.; Karasimav, Ö.; Kılıç, Z.; Yaşar, E.; Bodur, H. Radiation-induced lumbosacral plexopathy and pelvic insufficiency fracture: A case report of unique coexistence of complications after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Joint Dis. Relat. Surg. 2024, 35, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, M.T.; Constine, L.S.; Okunieff, P. Normal tissue tolerance dose metrics for radiation therapy of major organs. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2007, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, B.; Lyman, J.; Brown, A.; Cola, L.; Goitein, M.; Munzenrider, J.E.; Shank, B.; Solin, L.J.; Wesson, M. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1991, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumazawa, T.; Shiba, S.; Miyasaka, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Miyasaka, Y.; Ohtaka, T.; Kiyohara, H.; Ohno, T. Lumbosacral plexopathy after carbon-ion radiation therapy for postoperative pelvic recurrence of rectal cancer: Subanalysis of a prospective observational study (GUNMA 0801). Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2025, 10, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Gao, X.S.; Li, W.; Liu, P.; Qin, S.B.; Dou, Y.B.; Li, H.Z.; Shang, S.; Gu, X.B.; Ma, M.W.; et al. Contouring lumbosacral plexus nerves with MR neurography and MR/CT deformable registration technique. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 818953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamabe, A.; Ishii, M.; Kamoda, R.; Sasuga, S.; Okuya, K.; Okita, K.; Akizuki, E.; Miura, R.; Korai, T.; Takemasa, I. Artificial intelligence-based technology to make a three-dimensional pelvic model for preoperative simulation of rectal cancer surgery using MRI. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2022, 6, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, G.; Liu, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.; Wang, D.; Luo, J.; Wells, W.M.; He, S. Deep learning–based automatic segmentation of lumbosacral nerves on CT for spinal intervention: A translational study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, E.; Campetella, M.; Marino, F.; Gavi, F.; Moretto, S.; Pastorino, R.; Bizzarri, F.P.; Pierconti, F.; Gandi, C.; Bientinesi, R. Preoperative risk factors for failure after fixed sling implantation for post-prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence (FORESEE): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 77, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Side | Specific Assessment | Nerve Roots | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor (Strength) | Bilateral | Hip Flexion—psoas/iliacus | L1–L4 | 5/5 |

| Bilateral | Knee Extension—quadriceps femoris | L2–L4 | 5/5 | |

| Right | Foot Dorsiflexion—tibialis anterior | L4 | 0/5 or 1/5 | |

| Right | Hallux extension—extensor hallucis longus | L5 | 0/5 or 1/5 | |

| Right | Foot Plantarflexion—gastrocnemius/soleus | S1 | 0/5 or 1/5 | |

| Sensory | Left | Dermatomal Pain Sensation | L5, S1 | Decreased sensation to pin prick |

| Right | Dermatomal Pain Sensation | L4, L5, S1 | Decreased sensation to pin prick | |

| Deep Tendon Reflexes (DTRs) | Left | Patellar Reflex | L2–L4 | 2+ |

| Right | Patellar Reflex | L2–L4 | 2+ | |

| Left | Achilles Reflex | S1–S2 | 0 | |

| Right | Achilles Reflex | S1–S2 | 0 | |

| Other Findings | Positive Homan’s sign bilaterally. Right ankle edema | |||

| Comments | Patient requires walker to ambulate |

| Side/Muscle | Nerve | Root | Ins Act | Fibs | Psw | Recrt | Int Pat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L/Tibialis Anterior | Deep Fibular | L4–L5 | Incr | 3+ | 4+ | Rapid | 50% |

| L/Extensor Digitorum Brevis | Deep Fibular | L5, S1 | Incr | 2+ | 3+ | Rapid | 50% |

| L/Extensor Hallucis Longus | Deep Fibular | L5, S1 | Incr | 2+ | 3+ | Rapid | 50% |

| L/Gastrocnemius | Tibial | S1–S2 | Incr | 2+ | 4+ | Rapid | 50% |

| L/Vastus Medialis | Femoral | L2–L4 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| L/Biceps Femoris Long Head | Sciatic | L5–S2 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| L/Tensor Fasciae Latae | Superior Gluteal | L4, L5, S1 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| L/Gluteus Maximus | Inferior Gluteal | L5–S2 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| L/Lumbar Paraspinal Mid | Rami | L3, L4 | Nml | Nml | Nml | ||

| L/Lumbar Paraspinal Low | Rami | L5–S1 | Nml | Nml | Nml | ||

| R/Tibialis Anterior | Deep Fibular | L5, S1 | Incr | 4+ | 4+ | Rapid | 25% |

| R/Extensor Digitorum Brevis | Deep Fibular | L4, L5 | Incr | 4+ | 3+ | Rapid | 25% |

| R/Extensor Hallucis Longus | Deep Fibular | L5, S1 | Incr | 3+ | 4+ | Rapid | 25% |

| R/Gastrocnemius | Tibial | S1, S2 | Incr | 3+ | 3+ | Rapid | 25% |

| R/Vastus Medialis | Femoral | L2–L4 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| R/Biceps Femoris Long Head | Sciatic | L5–S2 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| R/Tensor Fasciae Latae | Superior Gluteal | L4, L5, S1 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| R/Gluteus Maximus | Inferior Gluteal | L5–S2 | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml | Nml |

| R/Lumbar Paraspinal Mid | Rami | L3, L4 | Nml | Nml | Nml | ||

| R/Lumbar Paraspinal Low | Rami | L5–S1 | Nml | Nml | Nml |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathew, E.; Meetheen, R.; Shivnani, A.; Dickerman, R. Unilateral to Bilateral Lumbosacral Plexopathy After Radiation Therapy: A Case Report. Radiation 2025, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/radiation5040036

Mathew E, Meetheen R, Shivnani A, Dickerman R. Unilateral to Bilateral Lumbosacral Plexopathy After Radiation Therapy: A Case Report. Radiation. 2025; 5(4):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/radiation5040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathew, Ezek, Reyhan Meetheen, Anand Shivnani, and Rob Dickerman. 2025. "Unilateral to Bilateral Lumbosacral Plexopathy After Radiation Therapy: A Case Report" Radiation 5, no. 4: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/radiation5040036

APA StyleMathew, E., Meetheen, R., Shivnani, A., & Dickerman, R. (2025). Unilateral to Bilateral Lumbosacral Plexopathy After Radiation Therapy: A Case Report. Radiation, 5(4), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/radiation5040036