The Mediating Role of Travel Destination Engagement in the Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity of Dairy Products: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Definitions of Country Image

2.2. Country Image and Tourism

2.3. Consumer-Based Brand Equity

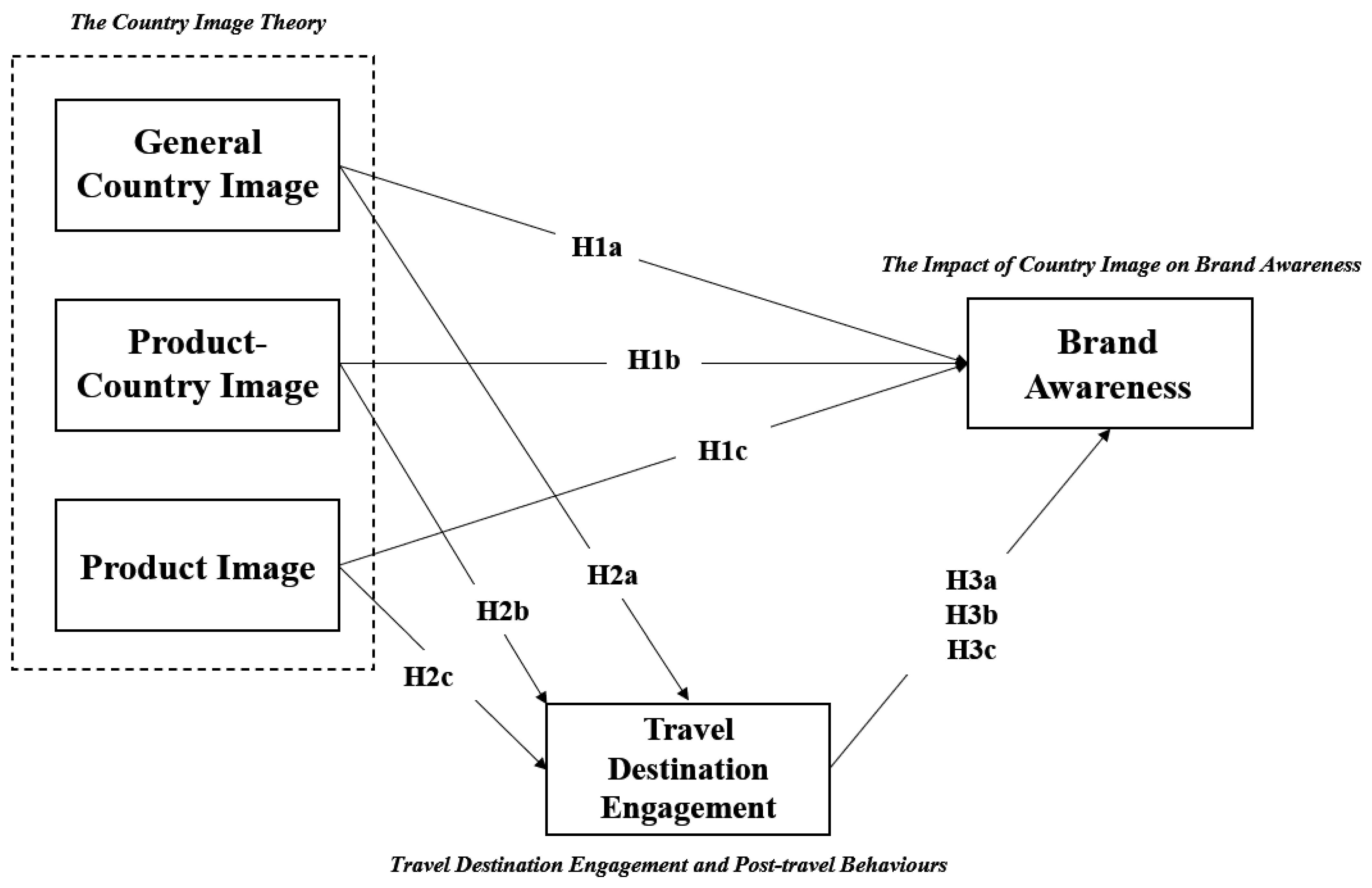

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity

3.2. Effects of Country Images on Travel Destination Engagement

3.3. The Role of Travel Destination Engagement in Consumer-Based Brand Equity

4. Methodology

4.1. The Context of the Present Study

4.2. Questionnaire Design and Measurement

4.3. Sampling

5. Results

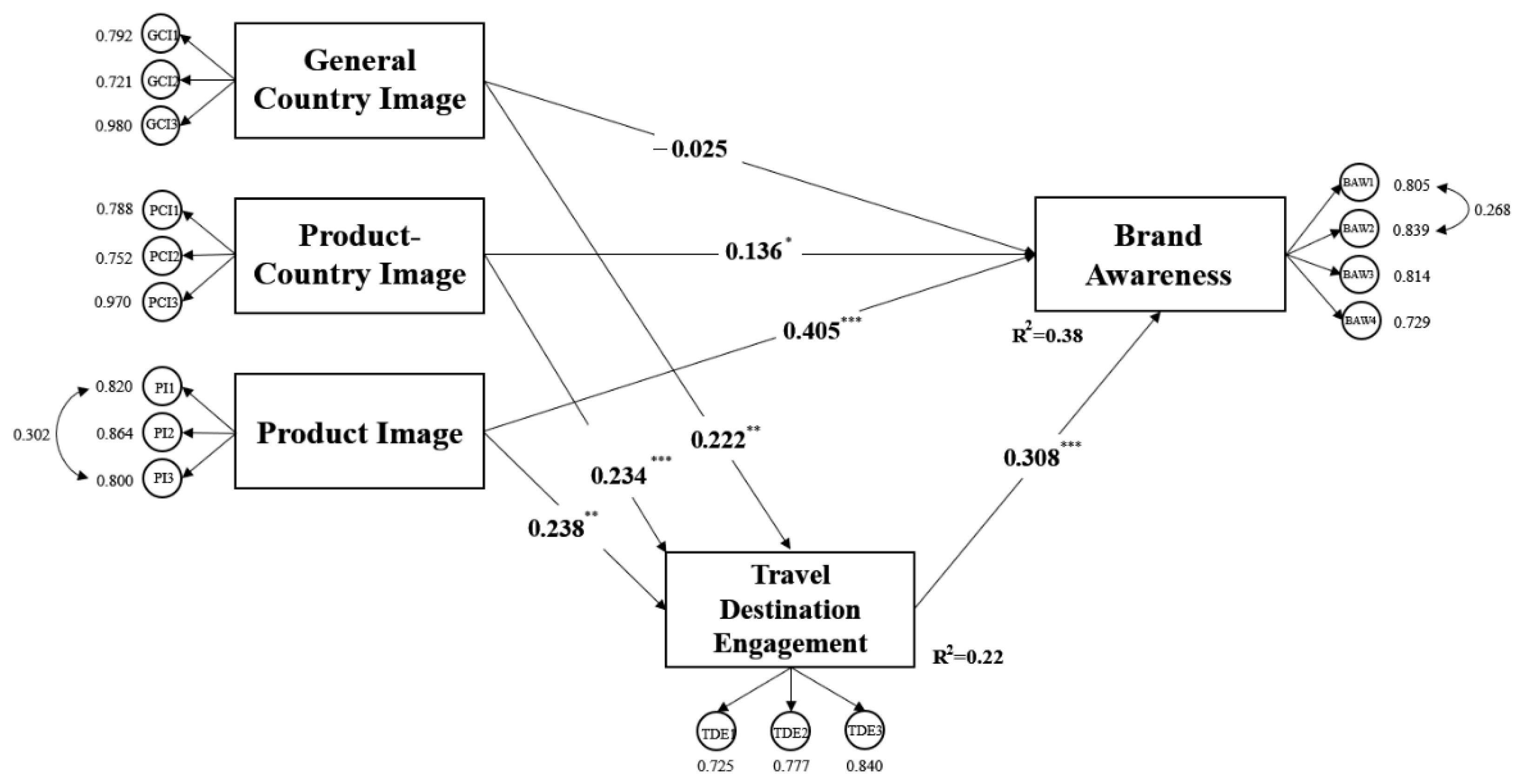

5.1. The Measurement Model

5.2. The Structural Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelwahab, D., San-Martín, S., & Jiménez, N. (2022). Does regional bias matter? Examining the role of regional identification, animosity, and negative emotions as drivers of brand switching: An application in the food and beverage industry. Journal of Brand Management, 29, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, L. S. (2008). Country-of-origin, animosity and consumer response: Marketing implications of anti-Americanism and Francophobia. International Business Review, 17(4), 402–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S., Bengtsson, L., & Svensson, Å. (2021). Mega-sport football events’ influence on destination images: A study of the 2016 UEFA European Football Championship in France, the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, and the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avloniti, C., Yfantidou, G., Papaioannou, A., Kouthouris, C., & Costa, G. (2025). Participant perceptions and destination image: Cognitive and affective dimensions in local sports contexts. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G., & Lopez, C. (2022). Reflective versus unreflective country images: How ruminating on reasons for buying a country’s products alters country image. International Business Review, 31(6), 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, J., Lockshin, L., Rungie, C., & Lee, R. (2015). Wine and tourism: A good blend goes a long way. In Ideas in marketing: Finding the new and polishing the old (pp. 309–312). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Cross-cultural research methods: Strategies, problems, applications. In Environment and cul-ture (pp. 47–82). Boston, MA; Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G., & Getz, D. (2005). Linking wine preferences to the choice of wine tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanti, M. M., Rohman, F., & Irawanto, D. (2014). Investigating the image of Japanese food on intention of behavior: Indonesian intention to visit Japan. Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies, 2(2), 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2023). Co-creative tourism experiences–A conceptual framework and its application to food & wine tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(5), 668–692. [Google Scholar]

- Cham, T. H., Lim, Y. M., Sia, B. C., Cheah, J. H., & Ting, H. (2021). Medical tourism destination image and its relationship with the intention to revisit: A study of Chinese medical tourists in Malaysia. Journal of China Tourism Research, 17(2), 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S., Wiitala, J., & Fu, X. (2019). The impact of country image and destination image on US tourists’ travel intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., Zhou, Z., Zhan, G., & Zhou, N. (2020). The impact of destination brand authenticity and destination brand self-congruence on tourist loyalty: The mediating role of destination brand engagement. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100402. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J. Y. J., & Kim, S. S. (2018). Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demangeot, C., & Broderick, A. J. (2016). Engaging customers during a website visit: A model of website customer engagement. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(8), 814–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nisco, A., Mainolfi, G., Marino, V., & Napolitano, M. R. (2015). Tourism satisfaction effect on general country image, destination image, and post-visit intentions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21(4), 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1), 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, T., Jiang, H., Deng, X., Zhang, Q., & Wang, F. (2020). Government intervention, risk perception, and the adoption of protective action recommendations: Evidence from the COVID-19 prevention and control experience of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S., Papadopoulos, N., & Kim, S. S. (2011). An integrative model of place image: Exploring relationships between destination, product, and country images. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A., Park, E., Kim, S., & Yeoman, I. (2018). What is food tourism? Tourism Management, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (1998). Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2), 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. R., & Mathur, A. (2005). The value of online surveys. Internet Research, 15(2), 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S., & Slocum, S. L. (2013). Food and tourism: An effective partnership? A UK-based review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. M., & Lynch, J. G. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(4), 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 10(6), 269–314. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods for SEM with nonnormal and categorical data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M. J. S. D., Sousa, B. B., Carvalho, T. M., & Teixeira, A. (2025). The internationalization of the portuguese textile sector into the Chinese market: Contributions to destination image. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2022). Dairy production and products: Gateway to dairy production and products. Available online: http://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/en/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-De los Salmones, M. D. M., Herrero, A., & San Martin, H. (2022). The effects of macro and micro country image on consumer brand preferences. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 34(2), 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishna, S., Malthouse, E. C., & Lawrence, J. M. (2019). Managing customer engagement at trade shows. Industrial Marketing Management, 81, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K. G. (2005). Food quality and safety: Consumer perception and demand. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 32(3), 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). An introduction to structural equation modeling. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R (pp. 1–29). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C. M. (1989). Country image: Halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P., Evers, U., Miles, M. P., & Daly, T. (2018). Customer engagement and the relationship between involvement, engagement, self-brand connection and brand usage intent. Journal of Business Research, 88, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. C. (2009). Food tourism reviewed. British Food Journal, 111(4), 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K., Kemper, J., Lang, B., Conroy, D., & Frethey-Bentham, C. (2025). Threat or opportunity? A stakeholder perspective on country of origin brand and promoting gene edited foods. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmefjord, K. (2000, November 15–19). Synergies in linking products, industries and place? Is cooperation between tourism and food industries a local coping strategy in Lofoten and Hardanger. Whether, How and Why Regional Policies Are Working in Concert with Coping Strategies Locally? Work-Shop, Joensuu, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M. H., Pan, S. L., & Setiono, R. (2004). Product-, corporate-, and country-image dimensions and purchase behavior: A multicountry analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Choi, H. S. C. (2019). Developing and validating a multidimensional tourist engagement scale (TES). The Service Industries Journal, 39(7–8), 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Álvarez, R., Cambra-Fierro, J. J., & Fuentes-Blasco, M. (2020). The interplay between social media communication, brand equity and brand engagement in tourist destinations: An analysis in an emerging economy. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, U., Koch, C., Varga, N., & Zhao, F. (2018). Country of ownership change in the premium segment: Consequences for brand image. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(7), 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. E., Lloyd, S., & Cervellon, M. C. (2016). Narrative-transportation storylines in luxury brand advertising: Motivating consumer engagement. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. B., & Kwon, K. J. (2018). Examining the relationships of image and attitude on visit intention to Korea among Tanzanian college students: The moderating effect of familiarity. Sustainability, 10(2), 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P., & Gertner, D. (2002). Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4–5), 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B., & Kastenholz, E. (2015). Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches–Towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8–9), 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R., & Lockshin, L. (2011). Halo effects of tourists’ destination image on domestic product perceptions. Australasian Marketing Journal, 19(1), 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R., & Lockshin, L. (2012). Reverse country-of-origin effects of product perceptions on destination image. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Yao, Y., & Fan, D. X. (2019). Evaluating tourism market regulation from tourists’ perspective: Scale development and validation. Journal of Travel Research, 59, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., & Jesus, S. (2019). How perceived risk and animosity towards a destination may influence destination image and intention to revisit: The case of Rio de Janeiro. Anatolia, 30(4), 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., & Sarmento, E. M. (2019). Place attachment and tourist engagement of major visitor attractions in Lisbon. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(3), 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T., Serrano López, A. L., Pérez Gálvez, J. C., & Carpio Álvarez, S. D. (2017). Food motivations in a tourist destination: North American tourists visiting the city of Cuenca, Ecuador. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 29(4), 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, P., Krishnan, V., Westjohn, S. A., & Zdravkovic, S. (2014). The spillover effects of prototype brand transgressions on country image and related brands. Journal of International Marketing, 22(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A. A., & Carter, L. L. (2011). The affective and cognitive components of country image: Perceptions of American products in Kuwait. International Marketing Review, 28(6), 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainolfi, G., & Marino, V. (2020). Destination beliefs, event satisfaction and post-visit product receptivity in event marketing. Results from a tourism experience. Journal of Business Research, 116, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I. M., & Eroglu, S. (1993). Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. Journal of Business Research, 28(3), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R., & Hall, C. M. (2004). The post-visit consumer behaviour of New Zealand winery visitors. Journal of Wine Research, 15(1), 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, L., & Kleppe, I. A. (2005). Country and destination image–Different or similar image concepts? The Service Industries Journal, 25(4), 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J. G., Raggio, R. D., & Folse, J. A. G. (2016). Brand authenticity: Testing the antecedents and outcomes of brand management’s passion for its products. Psychology & Marketing, 33(6), 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Palau-Saumell, R., Forgas-Coll, S., Amaya-Molinar, C. M., & Sánchez-García, J. (2016). Examining how country image influences destination image in a behavioral intentions model: The cases of Lloret De Mar (Spain) and Cancun (Mexico). Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(7), 949–965. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, N., & Heslop, L. A. (2014). Product-country images: Impact and role in international marketing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pappu, R., Quester, P. G., & Cooksey, R. W. (2007). Country image and consumer-based brand equity: Relationships and implications for international marketing. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5), 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, R., & Dias, Á. (2021). The influence of brand experiences on consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Brand Management, 28, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C., & Loureiro, S. M. C. (2018). Consumer-based approach to customer engagement–The case of luxury brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S., Cai, L., Zhang, Y., & Chen, Z. (2016). Destination image of Japan and social reform generation of China: Role of consumer products. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(3), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can Likert-type scales be treated as continuous? Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, K. P., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Advancing the country image construct. Journal of Business Research, 62, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubera, G., Ordanini, A., & Griffith, D. A. (2011). Incorporating cultural values for understanding the influence of perceived product creativity on intention to buy: An examination in Italy and the US. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(4), 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, P., Alonso, A., & Sheridan, L. (2009). Expanding the destination image: Wine tourism in the Canary Islands. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(5), 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Arcos, M. M., Sánchez-Fernández, R., & Pérez-Mesa, J. C. (2020). Is there an image crisis in the Spanish vegetables? Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 32(3), 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, J. M., Arora, S. D., & Vatavwala, S. (2024). Developing an emic scale on consumer-based brand equity for packaged food brands. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 30(6–7), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sio, K. P., Fraser, B., & Fredline, L. (2024). A contemporary systematic literature review of gastronomy tourism and destination image. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(2), 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuras, D., Dimara, E., & Petrou, A. (2006). Rural tourism and visitors’ expenditures for local food products. Regional Studies, 40(7), 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S., & Costello, C. (2009). Culinary tourism: Satisfaction with a culinary event utilizing importance-performance grid analysis. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 15(2), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C. W., Meng, X. L., Tao, R., & Umar, M. (2022). Chinese consumer confidence: A catalyst for the outbound tourism expenditure? Tourism Economics: The Business and Finance of Tourism and Recreation, 29, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B., Jafari, A., & O’Gorman, K. (2014). Keeping your audience: Presenting a visitor engagement scale. Tourism Management, 42, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A., Croy, G., & Mair, J. (2013). Social media in destination choice: Distinctive electronic word-of-mouth dimensions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Villamediana-Pedrosa, J. D., Vila-López, N., & Küster-Boluda, I. (2020). Predictors of tourist engagement: Travel motives and tourism destination profiles. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L., Li, D., Barnes, B. R., & Ahn, J. (2012). Country image, product image and consumer purchase intention: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Business Review, 21(6), 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. (2025). The impact of brand identification, brand image, and brand love on brand loyalty: The mediating role of customer value co-creation in hotel customer experience. Frontiers in Communication, 10, 1626744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Jin, W., & Lin, Z. (2018). Tourist post-visit attitude towards products associated with the destination country. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2018). An investigation into the perceptions of Chinese consumers towards the country-of-origin of dairy products. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(2), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2021). Do consumer ethnocentrism and animosity affect the importance of country-of-origin in dairy products evaluation? The moderating effect of purchase frequency. British Food Journal, 124(1), 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2022). The effects of risk aversion and uncertainty avoidance on information search and brand preference: Evidence from the Chinese dairy market. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 28(6), 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Isa, S. M., Ramayah, T., Wen, J., & Goh, E. (2021). Developing an extended model of self-congruity to predict Chinese tourists’ revisit intentions to New Zealand: The moderating role of gender. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(7), 1459–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N. M., Noor, M. N., & Mohamad, O. (2007). Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 16(1), 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., Vorhies, D. W., & Zhou, W. (2023). An integrated model of retail brand equity: The role of consumer shopping experience and shopping value. Journal of Brand Management, 30, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Xu, F., Leung, H. H., & Cai, L. A. (2016). The influence of destination-country image on prospective tourists’ visit intention: Testing three competing models. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(7), 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Tseng, C., & Chen, Y. C. (2018). How country image affects tourists’ destination evaluations: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(6), 904–930. [Google Scholar]

| Variables/Items | Factor Loading | Mean | Std. Deviation | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Country Image (GCI) | 0.874 | 0.702 | 0.839 | |||

| GCI1: ‘It is a country that has an image of an advanced country.’ | 0.792 | 5.70 | 1.081 | |||

| GCI2: ‘It is a country that is prestigious.’ | 0.721 | 5.47 | 1.156 | |||

| GCI3: ‘I dislike this country.’ (R) | 0.980 | 5.51 | 0.650 | |||

| Product–Country Image (PCI) | 0.878 | 0.709 | 0.828 | |||

| PCI1: ‘It is a country that has a nice environment for dairy products.’ | 0.788 | 6.39 | 0.717 | |||

| PCI2: ‘It is a country that has high dairy production standards.’ | 0.752 | 6.33 | 0.786 | |||

| PCI3: ‘It is a country that has good dairy products.’ | 0.970 | 6.16 | 0.693 | |||

| Product Image (PI) | 0.868 | 0.686 | 0.828 | |||

| PI1: ‘The dairy products from this country taste good.’ | 0.820 | 6.05 | 0.835 | |||

| PI2: ‘The dairy products from this country are safe.’ | 0.864 | 6.09 | 0.810 | |||

| PI3: ‘The dairy products from this country are trustable.’ | 0.800 | 6.05 | 0.876 | |||

| Travel Destination Engagement (TDE) | 0.825 | 0.612 | 0.784 | |||

| TDE1: ‘I seek a lot of information about this country.’ | 0.725 | 5.70 | 1.209 | |||

| TDE2: ‘I have many experiences in this country.’ | 0.777 | 5.90 | 1.090 | |||

| TDE3: ‘I would like to visit this country in the next 24 months if there is an opportunity.’ | 0.840 | 5.71 | 1.187 | |||

| Brand Equity (BEQ) | 0.875 | 0.637 | 0.745 | |||

| BEQ1: ‘If I have to choose among brands of dairy products, those from this country are definitely my choice.’ | 0.805 | 4.98 | 1.268 | |||

| BEQ2: ‘If I have to buy dairy products, I plan to buy those from this country even though there are other brands from other countries as good.’ | 0.839 | 5.03 | 1.246 | |||

| BEQ3: ‘If there is a dairy brand from other countries as good as those from this country, I prefer to buy the latter.’ | 0.814 | 5.18 | 1.171 | |||

| BEQ4: ‘It makes sense to buy dairy products from this country instead of any brands from other countries, even if they are the same.’ | 0.729 | 5.23 | 1.192 |

| Variables | Scale | Number | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of informants | 573 | ||

| Gender | 1. Female | 321 | 56.00% |

| 2. Male | 252 | 44.00% | |

| Age | 1. 18–29 | 251 | 43.80% |

| 2. 30–39 | 283 | 49.40% | |

| 3. 40–49 | 31 | 5.40% | |

| 4. 50 or more | 8 | 1.40% | |

| Education | 1. Uneducated | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2. Primary | 0 | 0.00% | |

| 3. Junior secondary | 10 | 1.70% | |

| 4. Senior secondary | 48 | 8.40% | |

| 5. Diploma | 120 | 20.90% | |

| 6. Bachelor | 334 | 58.30% | |

| 7. Masters | 57 | 9.90% | |

| 8. Doctorates | 4 | 0.70% | |

| Location | 1. City | 341 | 59.50% |

| 2. County | 116 | 20.20% | |

| 3. Town | 76 | 13.30% | |

| 4. Village | 40 | 7.00% | |

| The annual household income per capita before tax (CNY) | 1. 20,000 or less | 114 | 19.90% |

| 2. 20,001–49,999 | 242 | 42.20% | |

| 3. 50,000–99,999 | 112 | 19.50% | |

| 4. 100,000–199,999 | 77 | 13.40% | |

| 5. 200,000 or more | 28 | 4.90% | |

| Preferred country of origin | 1. Australia | 176 | 30.72% |

| 2. New Zealand | 159 | 27.75% | |

| 3. China Mainland | 143 | 24.96% | |

| 4. Netherlands | 40 | 6.98% | |

| 5. Germany | 16 | 2.79% | |

| 6. USA | 10 | 1.75% | |

| 7. UK | 9 | 1.57% | |

| 8. Switzerland | 5 | 0.87% | |

| 9. Others | 15 | 2.62% |

| Global Country Image | Product Image | Product–Country Image | Travel Destination Engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Image | 0.554 | |||

| Product–Country Image | 0.510 | 0.380 | ||

| Travel Destination Engagement | 0.391 | 0.375 | 0.404 | |

| Brand Equity | 0.205 | 0.478 | 0.328 | 0.412 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | CFI | IFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | 194.383 | 94 | 2.068 | <0.001 | 0.974 | 0.974 | 0.967 | 0.043 | 0.05 | 310 |

| Structural model | 264.407 | 95 | 2.783 | <0.001 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.945 | 0.069 | 0.064 | 378 |

| Recommended value | <3.00 | ≥0.900 | ≥0.900 | ≥0.900 | <0.080 | <0.080 |

| Path | Effect | Standardized Estimate | Lower Interval | Upper Interval | Hypothesis | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCI→BEQ | Direct | −0.025 | −0.147 | 0.099 | H3a Supported | Full |

| GCI→TDE→BEQ | Indirect | 0.222 ** | 0.158 | 0.303 | ||

| PCI→BEQ | Direct | 0.136 * | 0.020 | 0.264 | H3b Supported | Partial |

| PCI→TDE→BEQ | Indirect | 0.231 ** | 0.166 | 0.308 | ||

| PI→BEQ | Direct | 0.405 *** | 0.288 | 0.510 | H3c Supported | Partial |

| PI→TDE→BEQ | Indirect | 0.041 * | 0.014 | 0.084 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, R.; Ramsaran, R.; Wibowo, S. The Mediating Role of Travel Destination Engagement in the Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity of Dairy Products: Evidence from China. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050225

Yang R, Ramsaran R, Wibowo S. The Mediating Role of Travel Destination Engagement in the Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity of Dairy Products: Evidence from China. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050225

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Rongbin, Roshnee Ramsaran, and Santoso Wibowo. 2025. "The Mediating Role of Travel Destination Engagement in the Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity of Dairy Products: Evidence from China" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050225

APA StyleYang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2025). The Mediating Role of Travel Destination Engagement in the Effects of Country Images on Consumer-Based Brand Equity of Dairy Products: Evidence from China. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050225