Champing—A Netnography Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How is Champing represented and promoted?

- RQ2: How do visitors describe and evaluate their Champing experiences?

- RQ3: Where does Champing fit as a form of camping and staycation experience?

2. Champing Camping and Staycations

3. Methods

- Setting research objectives—analyzing the Champing proposition through website promotion and guest reviews;

- Entrée—selecting the Champing website as the online field site;

- Data collection—gathering promotional text, images, and reviews displayed for each church;

- Analysis and interpretation—conducting content and thematic analysis;

- Research ethics—applying university research protocols.

- Promotional text—church characteristics (age, notable features), operational status (in-service or not), facilities (e.g., toilets, bedding), local attractions (natural or cultural), and cultural associations (literary or historical connections).

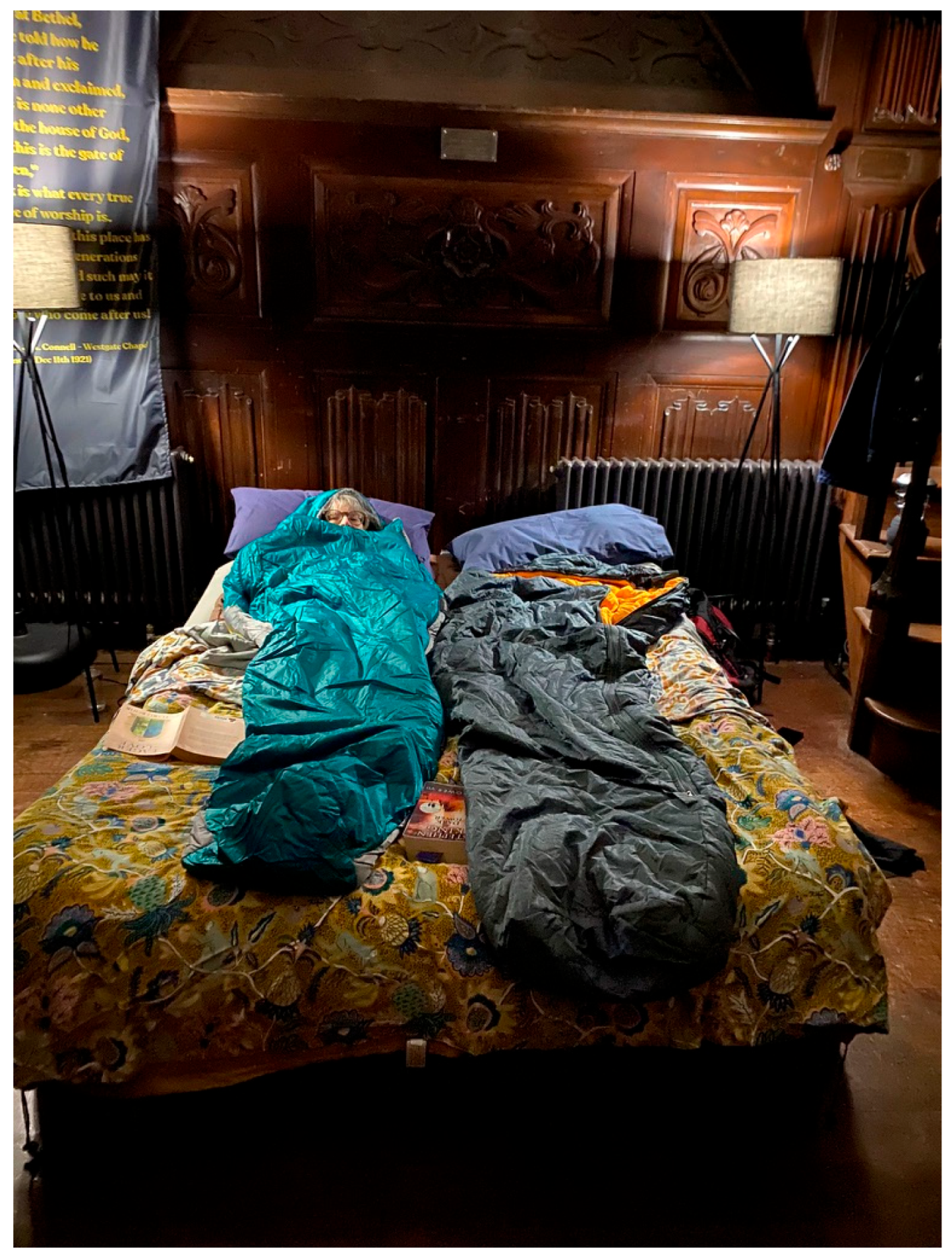

- Images—types of visual content (camp beds, kitchen area, seating area, exterior view, surrounding landscape, entrance door, stained-glass windows).

- Guest reviews—themes relating to atmosphere, local hospitality (pubs/restaurants), natural surroundings, and visitor origin (local or international).

4. Findings

4.1. Content Analysis of the Champing Website Text

4.2. Content Analysis of the Champing Website Images

4.3. Content Analysis of Champers Reviews of Their Champing Experience

4.4. Thematic Analysis of Champers Reviews

We stayed here (All Saints in Aldwincle,) in August 2020 for one night, our second experience Champing… The church itself was easy to find, beautiful and old with a sense of peace and serenity. There were a couple of ‘cold spots’ as the night progressed, and we had a lovely rainstorm outside which made the inside feel like a sanctuary. Champer A All Saints, Aldwincle

Two-night stay with our dogs Doris & Rupert. What a great adventure and amazing experience. Time to unwind and embrace the tranquil and peaceful setting. We had everything we needed and wow what a sunrise we were treated to through the stained-glass window which was unforgettable. Such nice touches, tea, coffee, milk and biscuits for Doris and Rupert.! Champer C St Botolph’s in Limpenhoe, Norfolk

Wow, wow & thrice wow… a magical weekend, gorgeous church, everything had been well thought out… a weekend of complete relaxation. Owls at night a partying, a little owl in the churchyard… bliss. Thai four two in Rochester does great vegan options. Champer D St James’ in Cooling, Kent

We had a fantastic time Champing. The church, St Andrew’s in Wroxeter, is beautiful and we had everything we needed. We spent hours exploring every detail and playing hide and seek in the pews. Our four-year-old adored the fake candles. It was a perfect break, and we’ll definitely do this again in another church. Thank you! Champer E St Andrew’s

We drove to Langport from Bristol, slept overnight in the church and did a tandem [bike ride] tour the next day around S Somerset to stay at another Champing church at Queen Camel. Langport was quiet; a nice atmosphere in the church, lovely to have the building to ourselves and think of all the people who must have visited it over the centuries. Warm enough to swim in the R Parrett near the town. Thanks to all who made it possible. Champer F, Langport, All Saints (Somerset)

I rode my bicycle from Staffordshire to St Andrew Church in Wroxeter, Shropshire. April 2021. It was a great day to ride and an inspiring place to aim for up a few tricky hills. It is truly a magnificent Church and a privilege to be a sleep-over guest. I’ll definitely be going back and incorporating this and other Champing churches into future bicycle tours. In fact, I’ve booked another one already in Warwickshire to check out! As a cycling tourist to other cycling tourists I highly recommend this experience. It’s an unforgettable end to a day’s ride. For everyone else it’s a wonderful place to sleep over and a peaceful and relaxing location Champer G St Andrew in Wroxeter, Shropshire

This is the first time my grandson has ever slept in a church, it’s an experience he will never forget, he’s already telling his friends and anyone who will listen, all about it. I can’t recommend Champing highly enough. Champer H, St. Botolph’s

Champing was such an unusual and beautiful experience! Coming from a catholic country (we’re from Italy), allowing people to sleep in the very heart of churches (we did it in the choir) may sound a bit… destabilizing! On the contrary, the study found a very welcoming place: I was expecting an icy and damp church, but the study found a dry and warm one; everything looked prepared (kettle and tea and coffee facilities, sleeping bags and pillows, electric candles) with love and was spotlessly clean. Waking up in the morning with the sunlight coming through stained glass had no equal! It is considered that there’s a way to enjoy the stay for anyone: for someone who’s looking for quiet, for a place for thinking, for a religious approach or for simply sharing an out-of-beaten-track experience. Champer I St Mary’s in Edlesborough, Buckinghamshire

This is the second time me, my husband and 2 daughters (aged 10 and 11) have been champing and we LOVE it. It is well put together making it a warm and comfortable stay. We enjoyed our food and board games surrounded by such beauty….and waking up to sunshine pouring through the stained-glass windows is magical! Highly recommend, such a privilege to be able to stay overnight in a building with so much history. We will be back. Champer J St Mary the Virgin in Stansted Mountfitchet, Essex

Booked a one night stay to celebrate my 60th with five friend[s]. Absolutely perfect! Yes the weather was stunning, which made for a wonderful picnic outside, admiring beautiful views and a late night walk through surrounding wheat fields but regardless, the church was all I could have hoped for. Thirteenth century stonework, medieval carvings and tiles, Victorian painting, gorgeous stained glass. So much history to see and experience at close quarters. A fun-filled evening reading from the pulpit, singing with amazing acoustics and even a tune or two on the organ. Camp beds and chairs provided were of very high standard and hospitality tray greatly appreciated. The odd squeak of a bat and other night time noises added to the atmosphere. Couldn’t recommend more highly. Champer L, St Mary’s in Edlesborough

I stayed for one night on a solo trip and had a brilliant time. It was so amazing to have the space to myself. The instructions were great and I had all the aspects I needed. St Mary’s is in a great spot—you’re up on the hill so you get feeling of being on your own, but there are actually houses (and a bus stop!) just outside. I was on foot and found that the Swan in Northall was closer and easier to walk to (pavements all the way!) than the Travellers Rest. The food there was good and it was a nice friendly pub. Champer M, St Mary’s in Edlesborough, Buckinghamshire

5. Discussion of Findings

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Methodological Contributions

5.3. Practical Contributions

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| CCT | Churches Conservation Trust |

Appendix A

| Church Name | Camp Beds | Kitchen Area | Seating Area | Exterior Church View | Country View | Entrance Doors | Stained-Glass Church Windows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Saints in Aldwincle | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| All Saints in Claverley | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| All Saints in Langport | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| All Saints, Muggleswick | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| All Saints, Rotherby | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Andrew in Wroxeter | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Barnabas in Queen Camel | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Bartholomew’s in Failand | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| St Botolph’s in Limpenhoe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Cuthbert’s in Holme Lacy | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St George’s Church—Hindolveston | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Gwrhai, Penstrowed | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St James’ in Cooling | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Laurence in Hilmarton | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Luke in Clifton, West | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Mary the Virgin in Stansted Mountfitchet | Yes | ||||||

| St Mary’s Church in Arkengarthdale | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Mary’s Church in Burgh Parva, Melton Constable | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Mary’s Church, Longsleddale | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| St Mary’s in Edlesborough | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Nicholas in Berden | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Paul’s Church in Witherslack | Yes | Yes | |||||

| St Peter’s Church in Wolfhampcote | Yes | Yes | |||||

| St Peter’s Church, Bratton Fleming | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Thomas in Friarmere | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| St Dona in Llanddona, Beaumaris | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| All Saints, Laxfield | Yes | Yes | |||||

| St Leonard’s Church in Watlington | Yes | Yes | |||||

| St Mary Magdalene in Whitgift | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Tom Paine’s Chapel in Lewes | Yes |

References

- Addeo, F., Paoli, A. D., Esposito, M., & Bolcato, M. Y. (2019). Doing social research on online communities: The benefits of netnography. Athens Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H. (2019). Designing digital nudges for sustainable travel decisions [Doctoral dissertation, Umea University]. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1331709&dswid=6086 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Arizton. (2018). Camping tent market in Europe. industry outlook and forecast 2018−2023. Available online: https://www.arizton.com/market-reports/camping-tent-market-europe (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Barclays. (2019). The Great British staycation: The growing attraction of the UK for domestic holidaymakers. Barclays Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Bartl, M., Kannan, V. K., & Stockinger, H. (2016). A review and analysis of literature on netnography research. International Journal of Technology Marketing, 11(2), 165–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, A. (2017). Everyday aesthetics on staycation as a pathway to restoration. International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies, 4(2), 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, E., & Decrop, A. (2019). Paradoxes of Postmodern Tourists and Innovation in Tourism Marketing. In E. Fayos-Sola, & C. Cooper (Eds.), The future of tourism (pp. 131–154). Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- Blichfeldt, B. S., & Mikkelsen, M. (2013). Vacability and sociability as touristic attraction. Tourist Studies, 13(3), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A., & Pereira, C. (2017). Comfortable experiences in nature accommodation: Perceived service quality in Glamping. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 17, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, E., & Joppe, M. (2013). Trends in camping and outdoor hospitality—An international review. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, E., & Joppe, M. (2014). A critical review of camping research and direction for future studies. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(4), 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H. T., Jones, T. E., Weaver, D. B., & Le, A. (2020). The adaptive resilience of living cultural heritage in a tourism destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCT. (2017). The CCT stands ready! CCT. [Google Scholar]

- Cerović, Z. (2014). Innovative management of camping accommodation. Horizons: International Scientific Journal Series A, 13, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Wei, H. (2022). Minimalism in capsule hotels: Enhancing tourist responses by using minimalistic lifestyle appeals congruent with brand personality. Tourism Management, 93, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, H., & Miled, B. (2013). Are brand communities influencing brands through co-creation? A cross-national example of the brand AXE: In France and in Tunisia. International Business Research, 6, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., Lehto, X. Y., & Morrison, A. M. (2007). Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tourism Management, 28(1), 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R. M. (2018). Religiosity and voluntary simplicity: The mediating role of spiritual well-being. Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. (2010). Researching pilgrimage: Continuity and transformations. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(2), 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. (2016). The lifecycle of concepts: The case of ‘pilgrimage tourism’. Tourism Geographies, 18(3), 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, L., McDermott, M. L., & Wallace, R. (2017). Netnography: Range of practices, misperceptions, and missed opportunities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691770064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. A. (2025). Glamping: A review. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 49, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, L. (2009). Peace through tourism: The birthing of a new socio-economic order. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(Suppl. S4), 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, J., Nawijn, J., Geurts, S., Kinnunen, U., & Korpela, K. (2017). Holiday travel, staycations, and subjective well-being. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, S., & Song, H. (2016). Why tourists thirst for authenticity—And how they can find it, the conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-tourists-thirst-for-authenticity-and-how-they-can-find-it-68108 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Dickinson, J. E., Lumsdon, L. M., & Robbins, D. (2011). Slow travel: Issues for tourism and climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(3), 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissart, J. C. (2021). Can staycations contribute to a territorial transition towards slow recreation? Géocarrefour, 95(95/2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzurov Vargová, T., Gallo, P., Švedová, M., Litavcová, E., & Košíková, M. (2020). Non-traditional forms of tourism in Slovakia as a concept of competitiveness. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 30(Suppl. 2), 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efford, C. (2016). Parliamentary debate approves funding for The churches conservation trust. Available online: https://hansard.parliament.uk/pdf/commons/2016-02-29/b89ef779-0858-44a3-b7bb-c2df0b3dd841 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Filep, S., & Pearce, P. (2014). Tourist experience and fulfilment. Insights from positive. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, K., & Räikkönen, J. (2024). Instadolls on staycation–doll dramas narrating popular culture tourism and regional development. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen, A. (2002). Churches and statues: Cultural tourism in Finland. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(4), 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston. (2020). Draft grants to the churches conservation trust order 2020. Delegated Legislation Committee House of Commons. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J., & Lee, J. (2019). A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(3), 314–329. [Google Scholar]

- James, Z., Ravichandran, S., Chuang, N.-K., & Bolden, E., III. (2017). Using lifestyle analysis to develop lodging packages for staycation travelers: An exploratory study. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 18(4), 387–415. [Google Scholar]

- Jeuring, J., & Haartsen, T. (2018). The challenge of proximity: The (un) attractiveness of near-home tourism destinations. In Proximity and intraregional aspects of tourism (pp. 115–138). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, A., & Lee, S. M. (2007). Environmental reporting of global corporations: A content analysis based on website disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, D. (2016). Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(6), 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Martinez, C. M. J., & Johnson, C. (2021). Minimalism as a sustainable lifestyle: Its behavioral representations and contributions to emotional well-being. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, L. (2024). Walking The Netherlands’ new long-distance salt path. The Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I., & Kuljis, J. (2010). Applying content analysis to web-based content. Journal of Computing and Information Technology, 18(4), 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10(12), 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, I. E., Wu, J., Lin, Z., & Gong, T. E. (2024). Staycation: A review of definitions, trends, and intersections. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 0(0), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Maketing Research, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Validity in content analysis. Computerstrategien für die Kommunikationsanalyse, 291, 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z., Wong, I. A., Kou, I. E., & Zhen, X. (2021). Inducing wellbeing through staycation programs in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z., & Xiao, X. (2023). Parting thoughts XV: When nostalgic heritage sites become a leisure getaway haven. Leisure Sciences, 45(3), 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, N. (2017). Camping tourism. In L. L. Linda (Ed.), The SAGE international encyclopaedia of travel and tourism (pp. 219–225). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, D. Ø. (2022). Staycation. In Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing (pp. 246–248). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, G. (2008). Does one culture all think the same? An investigation of destination image perceptions from several origins. Tourism Review, 63(4), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. (2023). Who kept travelling and where did they go? Domestic travel by residents of SE Queensland, Australia. Tourism Geographies, 25(2–3), 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, E., Hanrahan, J., & Duddy, A. M. (2020). Application of the European tourism indicator system (ETIS) for sustainable destination management. Lessons from County Clare, Ireland. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(2), 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, A. (2024, August 4). What is ‘champing’? The new type of glamping, explained. Time Out. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. (2022). The secret history of ‘Staycation’. Merriam-Webster. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, M. V., & Blichfeldt, B. S. (2018). Grand Parenting by the Pool. Young Consumers, 19(2), 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C., Cheer, J. M., & Novelli, M. (2018). Overtourism: A growing global problem. The Conversation, 18(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mkono, M. (2020). Eco-anxiety and the flight shaming movement: Implications for tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(3), 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molz, J. G. (2009). Representing pace in tourism mobilities: Staycations, slow travel and the amazing race. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 7(4), 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H., & Chan, H. (2022). Millennials’ staycation experience during the COVID-19 era: Mixture of fantasy and reality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(7), 2620–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M., Cheer, J. M., Dolezal, C., Jones, A., & Milano, C. (2022). Introduction to niche tourism-contemporary trends and development. In Handbook of niche tourism (pp. xxiii–xxxii). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pangarkar, A., Shukla, P., & Charles, R. (2021). Minimalism in consumption: A typology and brand engagement strategies. Journal of Business Research, 127, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. A., & Gretzel, U. (2007). Success factors for destination marketing web sites: A qualitative meta-analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichierri, M., Petruzzellis, L., & Passaro, P. (2023). Investigating staycation intention: The influence of risk aversion, community attachment and perceived control during the pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(4), 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, S., Hartwell, H., Blake, A., & Hemingway, A. (2016). Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tourism Management, 55, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W. L., Park, S. Y., Pan, B., & Newman, P. (2019). Forecasting campground demand in US national parks. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W. S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (1992). Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel research, 30(4), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2020). Camping tourism: A review of recent international scholarship. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 28(1), 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, M. (2002). Space, sanctity and service; the English Cathedral as heterotopia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4(5), 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. V. (Ed.). (2015). Challenges in tourism research (Vol. 70). Channel View. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. L., & Font, X. (2014). Volunteer tourism, greenwashing and understanding responsible marketing using market signalling theory. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(6), 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J. L., Wiley, J. B., & Wirth, F. F. (2012). Who are the locavores? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(4), 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, R., & Wijesinghe, S. N. (2019). The evolution of the web and netnography in tourism: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 17–37). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. J., & Teye, V. B. (2009). Tourism and the lodging sector. Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Tritto, A. (2020). Environmental management practices in hotels at world heritage sites. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1911–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, N., & Margaryan, L. (2020). Integration of “Ideal Migrants”: Dutch lifestyle expat-reneurs in Swedish campgrounds. Rural Society. [Google Scholar]

- Varis, P. (2016). Digital ethnography. In A. Georgakopoulou, & T. Spilioti (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and digital communication (pp. 55–68). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- VisitEngland. (2014). Impact of crises on holiday taking behaviour. VisitEngland. [Google Scholar]

- Visit Scotland. (2024). Stay in a converted church in Scotland. Visit Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T. B., & Lee, T. J. (2022). Contributions to sustainable tourism in small islands: An analysis of the Cittàslow movement. In Island tourism sustainability and resiliency (pp. 1–21). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C., & Hardy, D. (1986). Goodnight campers!: The history of the British holiday camp. Mansell. [Google Scholar]

- Wixon, M. (2009). The great American staycation: How to make a vacation at home fun for the whole family (and your wallet!). Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I. A., Lin, Z., & Kou, I. T. E. (2023). Restoring hope and optimism through staycation programs: An application of psychological capital theory. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(1), 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q., Shen, H., & Hu, Y. (2022). “A home away from hem”: Exploring and assessing hotel staycation as the new normal in the Covid-19 era. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(4), 1607–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesawich, P. (2010). Are staycations here to stay? World Property Journal. Available online: https://www.worldpropertyjournal.com/us-markets/vacation-leisure-real-estate-1/real-estate-news-peter-yesawich-travel-trends-2010-travel-report-y-partnership-tourism-trends-orlando-theme-parks-disney-world-sea-world-universal-studios-2452.php (accessed on 20 September 2025).

| Theoretical Discussion | Finding | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| New and under-researched concepts | Champing as a tourism concept has received no empirical research. Staycations as a form of tourism are under-researched but gaining attention. Camping as a tourist form of lodging has also received limited research focus. | Brooker and Joppe (2013); De Bloom et al. (2017); Dissart (2021); Lin and Xiao (2023); Moon and Chan (2022) Pichierri et al. (2023); Rice et al. (2019); Rogerson and Rogerson (2020); Van Rooij and Margaryan (2020) |

| Camping is basic but authentic | Champing is a more authentic experience of basic tourist accommodation, providing the quality holistic activity of staying in a tent in nature. Camping is associated with the social benefits of personal rewards via opportunities to reconnect with simpler living practices, the natural environment, and campers making time for themselves, family, and friends. | (Bigné & Decrop, 2019; Brooker & Joppe, 2014; Cerović, 2014; Rogerson & Rogerson, 2020) |

| Staycation is a contested tourism concept | Staycations include concepts such as returning home, visiting a local place, travelling within the local community, and possibly overnight stays. | (James et al., 2017; Kou et al., 2024) |

| Staycation is local | A staycation involves local travel—local meaning staying within the country of residence and between 50 and 100 miles from home, potentially involving an overnight stay. | Dissart (2021); James et al. (2017); Stanton et al. (2012) |

| Staycations involve local differences | Staycations are about local culture and natural activities, and exploration of the unusual and differences between the destination and the tourist’s home environment. | (James et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2021; Kou et al., 2024; McKercher, 2023; Singh, 2015) |

| Staycations are authenticity, nostalgia, and novel | Tourists are looking to increase their perception of ‘true’ and novel through staycations. | (Dennett & Song, 2016; Dissart, 2021; Madsen, 2022; Singh, 2015; VisitEngland, 2014; Walker & Lee, 2022) |

| Staycations are slow-paced and affect well being | Staycations are about a slower pace, well-being, tranquility and a less-hurried rediscovery. They provide opportunities to develop life skills that can enhance psychological capital and promote well-being. | Dickinson et al. (2011); Jeuring and Haartsen (2018); Molz (2009); Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) |

| Environmental consideration | There is a trend where tourists want to stay local to reduce their environmental impact. | Andersson (2019); Mkono (2020) |

| Reaction against overtourism | A desire not to engage in overtourism due to poor quality, and the chance to appreciate familiar environments from the perspective of a local visitor. | Besson (2017); Koens et al. (2018); Milano et al. (2018); Singh (2015) |

| Church Name | Age of the Church | Notable Attributes | Toilet | Bedding | Service | Local Natural Attractions | Local Cultural Attractions | Literary/Famous Connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Saints, Laxfield, Suffolk | 14th century | Magnificent Tower; 15c carvings | Flush | Suffolk Countryside | Local market towns; Sutton Hoo | |||

| All Saints in Aldwincle, Northamptonshire | 13th century | The chambre chantry; chapel of 1489 | Compost | To Hire | River Nene; Rockingham Forest, Bramwell Park | Historical houses to visit | Birthplace of Poet John Dryden | |

| All Saints in Claverley, Shropshire | 675 | Medieval wall paintings; Norman architecture | Flush | No | Y | Shropshire Hills AONB | UNESCO Ironbridge; Gorge museums | |

| All Saints in Langport, Somerset | 15th century | Tower with views; historic interior | Compost | To Hire | Somerset Levels; River Parrett | Muchelney Abbey; Langport Heritage Centre | ||

| All Saints, Melton, Mowbury | 13th century | Robbert De Brett | Flush | Wreake Valley | Belvoir Castle; water park | |||

| All Saints, Muggleswick, County Durham | 18th century | Ruins of a medieval church | Flush | North Pennines AONB; Derwent Reservoir | ||||

| St Andrew in Wroxeter, Shropshire | Adjacent to Roman ruins of Viroconium | Compost | To Hire | Wroxeter Roman City; Shrewsbury Museum | ||||

| St Barnabas in Queen Camel, Somerset | 1291 | Tower; font eagle lectern | Flush | No | Y | Somerset Levels; Camel Hill | Haynes Motor Museum; Iron Age Fort | |

| St Bartholomew’s in Failand, Somerset | 1887 | Tapestry depicting Chaucer; oak doors | Flush | To Hire | Avon George—North Somerset countryside | Clifton Suspension Bridge | ||

| St Botolph’s in Limpenhoe, Norfolk | 12th century | Noman south doorway | Flush | To Hire | Y | Rivers and marshes | Norwich, Yarmouth | |

| St Cuthbert’s in Holme Lacy, Herefordshire | 1571 | 17C font; medieval stalls | Compost | To Hire | River Wye; Herefordshire countryside | Holme Lacy House; Hereford Cathedral | ||

| St Dona in Llanddona, Beaumaris, Anglesey | 1873 | Modern stained-glass window | Compost | To Hire | Y | Coast line | Oriel Mon artist home - | |

| St George’s Church—Hindolveston, Norfolk | 1932 | Lancet windows; brass setting | Flush | Pensthorpe Natural Park | North Norfolk Railway | |||

| St Gwrhai, Penstrowed, Caersws, Powys | 1860 | Flush | No | Dark Sky Discovery; River Severn | ||||

| St James’ in Cooling, Kent | 13th century | 500-year-old timber doors | Compost | No | North Kent Marshes; RSPB reserves | Cooling Castle; Rochester Cathedral | Featured in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations | |

| St Laurence in Hilmarton, Wiltshire | 12th century origins | Historic nave and chancel; village setting | Flush | To Hire | Y | North Wessex Downs AONB | Wiltshire Museum; historic houses | |

| St Leonard’s Church in Watlington, Oxfordshire | 12th century origins | Gothic windows | Flush | Y | Chiltern Hills AONB; Watlington Hill | Oxford | Filming location for Midsomer Murders | |

| St Luke in Clifton, West Cumbria | 19th century | Victorian architecture; stained glass | Flush | To Hire | Lake District National Park AONB | Penrith Castle; Hadrian’s Wall | Wordsworth; Harry Potter | |

| St Mary Magdalene in Whitgift, East Riding of Yorkshire | Grade one listed | Unusual clock face with XIII; riverside setting | Flush | No | Humberhead Peatlands; River Ouse | Goole Museum | ||

| St Mary the Virgin in Stansted Mountfitchet, Essex | 12th century | Norman architecture; historic graveyard | Hatfield Forest; Essex countryside | Mountfitchet Castle; House on the Hill Toy Museum | ||||

| St Mary’s Church in Arkengarthdale, North Yorkshire | 1800s | English gothic style | Flush | No | Yorkshire Dales National Park | Swaledale Museum; Richmond Castle; Dark Sky | James Herriot countryside | |

| St Mary’s Church in Burgh Parva, Melton Constable | 1903 | Medieval tower | Compost | Norfolk Coast AONB; Holt Country Park | Coloney of Grey Seals | |||

| St Mary’s Church, Longsleddale | 19th century | Remote valley church; stone architecture | Public | Lake District fells; Longsleddale Valley | Kendal Museum; local heritage trails | Postman Pat | ||

| St Mary’s in Edlesborough, Buckinghamshire | Medieval | Tower with spire; medieval architecture | Compost | To Hire | Chiltern Hills; Ivinghoe Beacon AONB | Ashridge Estate; Whipsnade Zoo | ||

| St Nicholas in Berden, Essex | 12th century origins | Historic nave and chancel; restored interior | Flush | To Hire | Y | Hatfield Forest; Essex countryside | Mountfitchet Castle; War Museum | |

| St Paul’s Church in Witherslack, Cumbria | 17th century origins | Set in Lake District National Park; stone architecture | Flush | Lake District fells; Whitbarrow Scar | Cartmel Priory | Wordsworth connections nearby | ||

| St Peter’s Church in Wolfhampcote, Warwickshire | 14th century | Limewashed walls; 14C carved screen | Compost | Daventry County Park; Oxford Canal | Braunston Marina | |||

| St Peter’s Church, Bratton Fleming, Southwest Barnstaple | 13th century origins | Restored church with tower | Flush | To Hire | Y | Exmoor National Park | Exmoor Zoological Park | R. D. Blackmore |

| St Thomas in Friarmere, Greater Manchester | 19th century | Vibrant stained glass | Compost | Marsden Moor Estate AONB | Peveril Castle | A Monster Calls was filmed at this church | ||

| Tom Paine’s Chapel in Lewes, East Sussex | 1687 | Built against the normal wall and defensive gateway. | Flush | Y | South Downs National Park | Lewes Castle; Tom Paine exhibitions | Home of Tom Paine, political philosopher |

| Camp Beds | Kitchen Area | Seating Area | Exterior Church View | Country View | Entrance Doors | Stained Glass Church Windows | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of images | 26 | 13 | 19 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 6 |

| Experience | Nature | Local Pubs/Restaurants | Local Attractions | Domestic Tourist | International Tourist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of mentions | 98 | 35 | 34 | 9 | 16 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, A.; Farache, F. Champing—A Netnography Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040191

Jones A, Farache F. Champing—A Netnography Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040191

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Adam, and Francisca Farache. 2025. "Champing—A Netnography Analysis" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040191

APA StyleJones, A., & Farache, F. (2025). Champing—A Netnography Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040191