Factors Influencing Geothermal-Based Health Tourism Development: A Thematic Analysis in Natural Hot Spring Destinations of Northwest Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tourism Industry and Health Tourism

1.2. Branding and Place Branding

1.3. Tourism Branding: Dimensions and Challenges

1.4. Literature Review

1.5. Objective

2. Materials and Methods

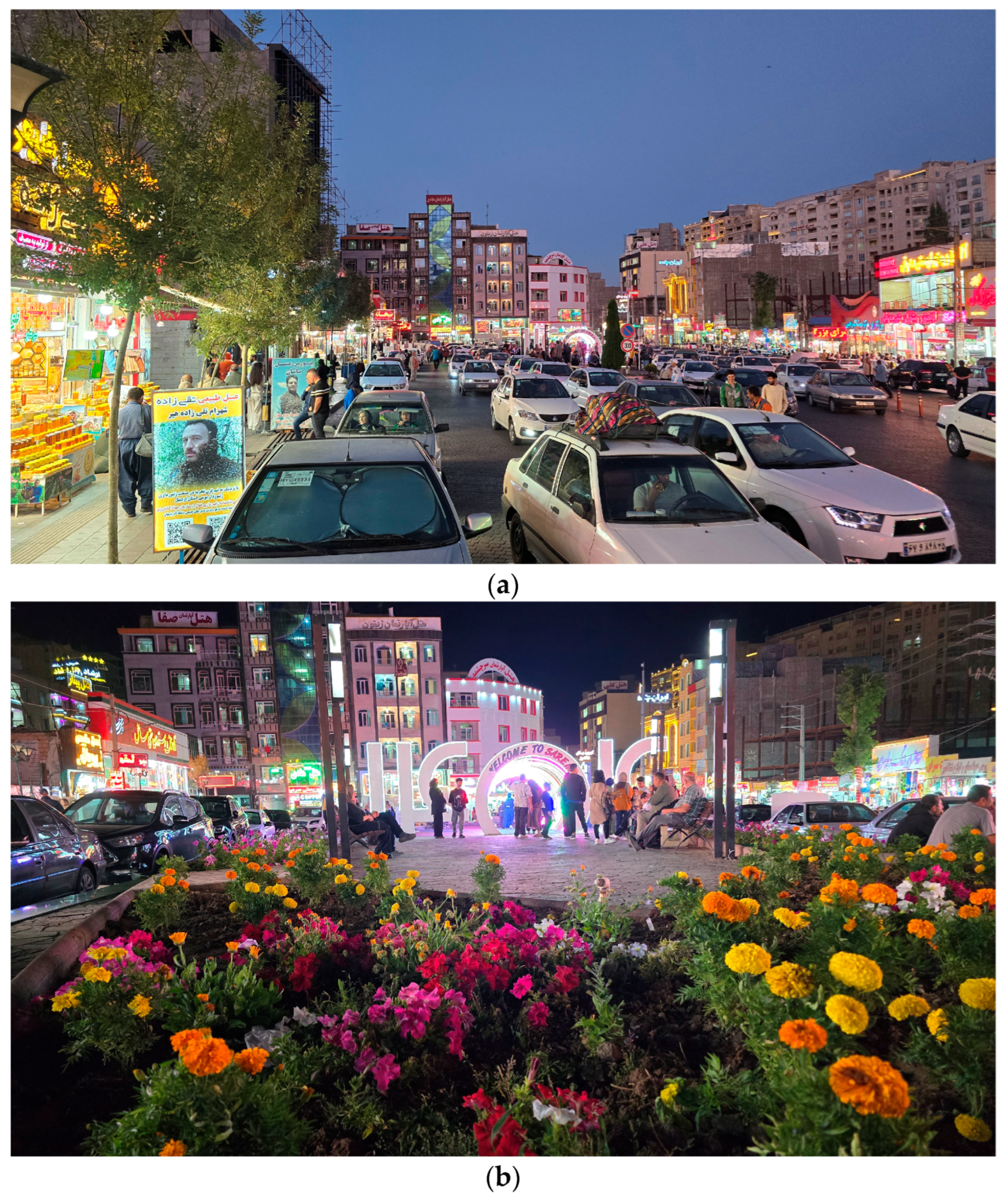

2.1. Study Area Description

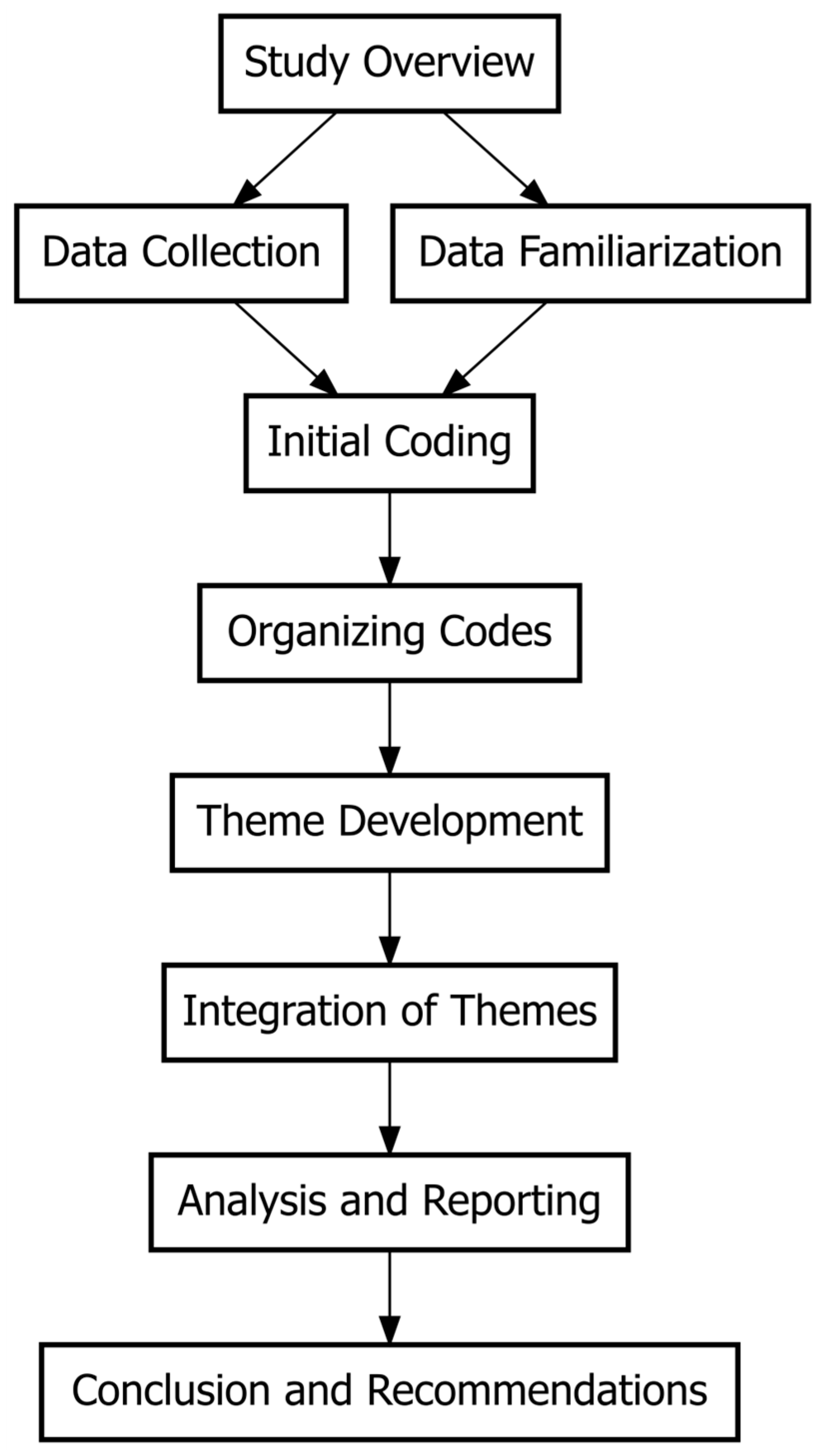

2.2. Methodology

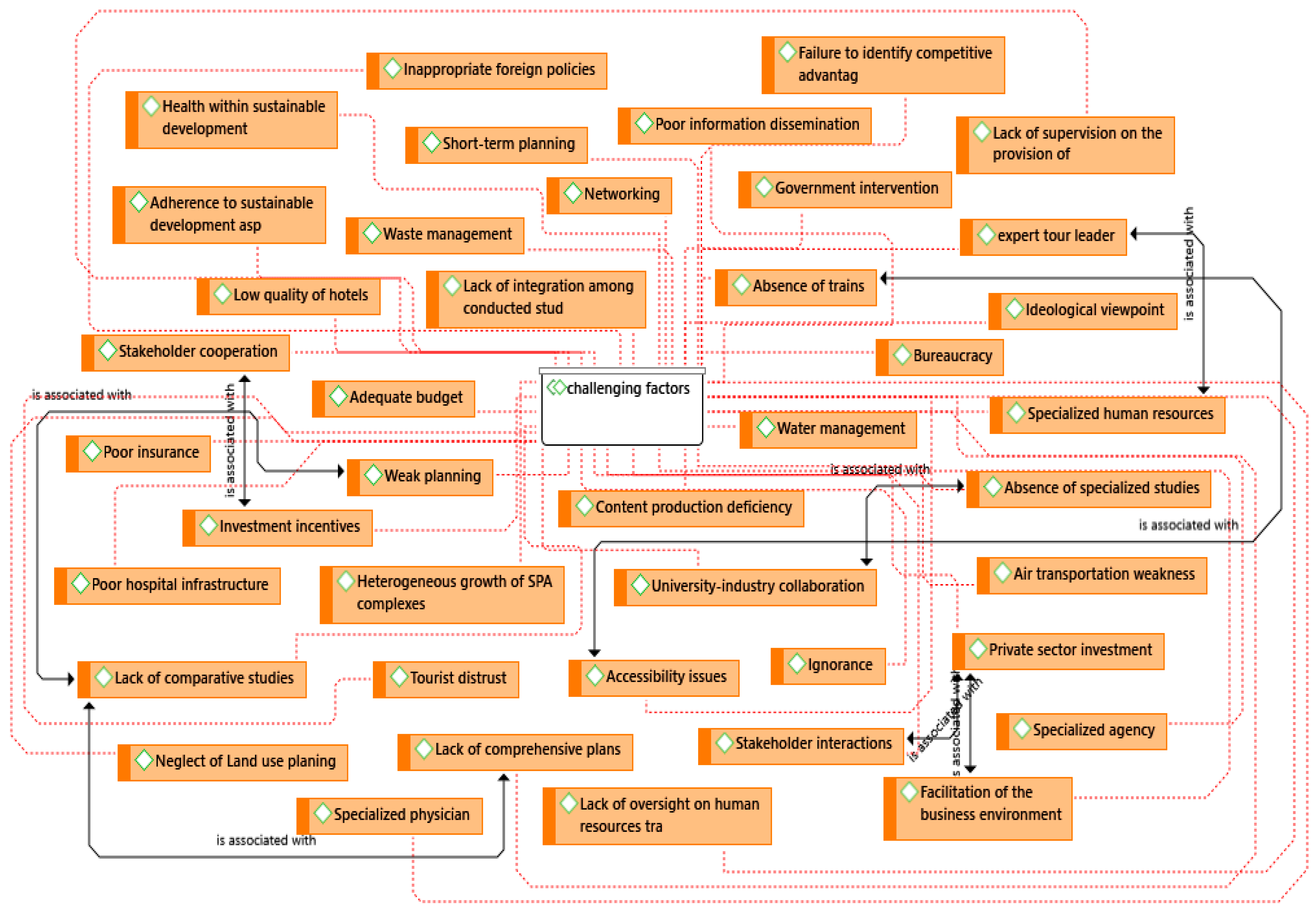

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Branding Challenges

“ … The role of infrastructures is crucial. Certain urban facilities must be available. When a tourist visits Sareyn, apart from hot springs and some existing shops, there is no other form of entertainment…’

4.2. Marketing Challenges

“ … If we look at the marketing and advertising domain one of the discussions is identifying the needs of tourists. What kind of tourists visit Sareyn? What are their needs? ….”

4.3. Governance Challenges

“ … Whether we succeed or not in this path depends on the planning of policymakers. It seems that the current progress is average, neither very strong nor very weak. In order for this trend to be more positive, we need some changes in regional policymaking and shifts in perspectives …”

4.4. Research Challenges

“ … The upcoming process requires research efforts to ensure compliance with all international brand standards, and we need scientific research to meet this need…”

4.5. Human Resource Strengthening Challenges

“ … Another challenge is the training of specialized personnel directly interacting with tourists. Minimum standards in hiring and employing these personnel have not been adhered to…”

4.6. Investment Challenges

“ … In government management, by delegating tourism management to the private sector and refraining from interfering, it can provide the groundwork for further development…”

4.7. Networking Challenges

“ … On the one hand, there is no communication network among tourism stakeholders. Integration of communication among universities, tourism organizations, economic actors in the tourism sector, and other relevant government agencies is essential …”

4.8. Challenges Related to Sustainable Development Principles

“ … Health tourism and sustainable development principles are closely related. If sustainability goals are not achieved, health will not be achieved. The existence of natural hot springs and favorable climates all contribute to public health and are essentially assets for sustainable development …”

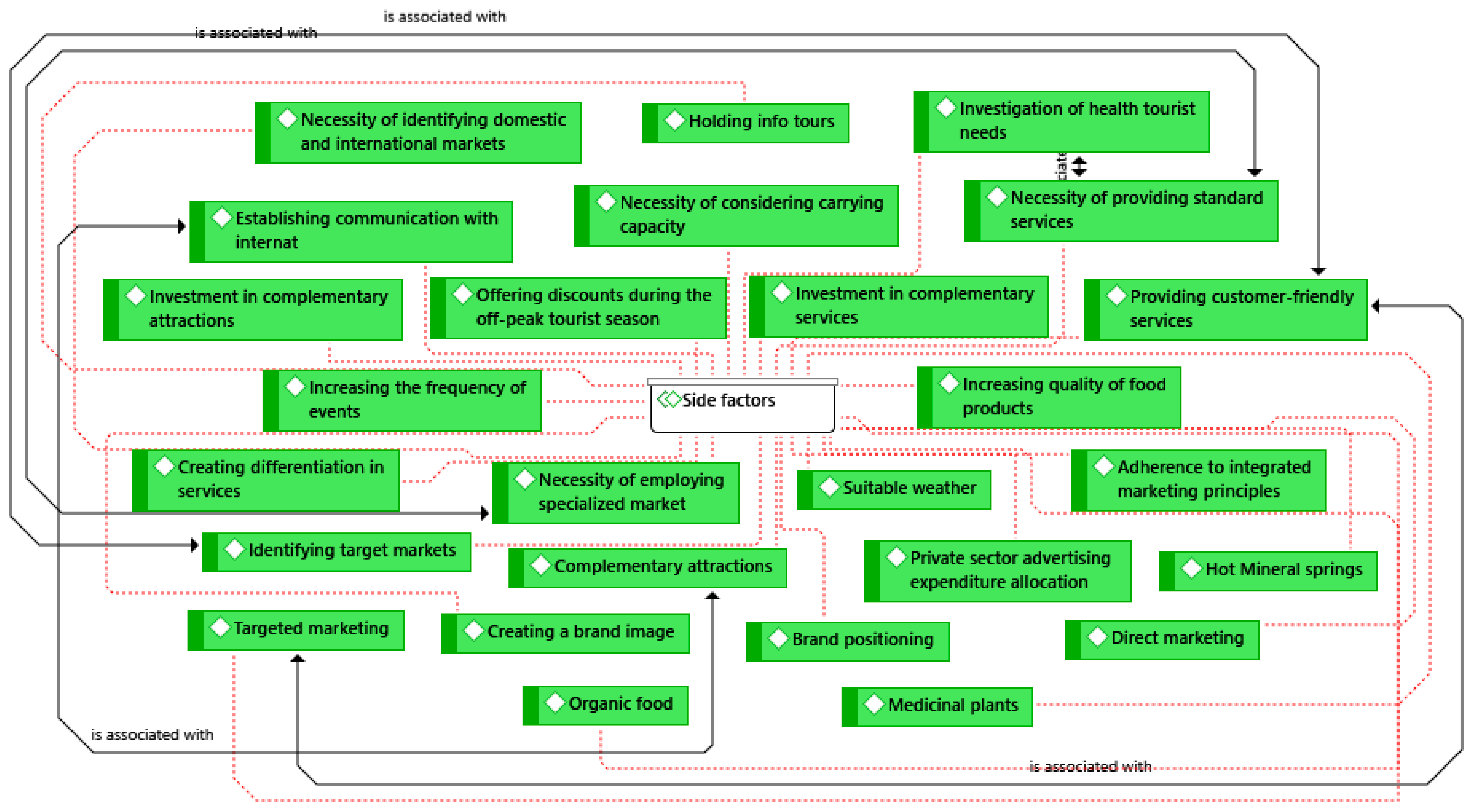

4.9. Side Factors

4.9.1. The Necessity of Marketing

“… The private sector must believe that it needs to allocate part of its budget to advertising…”“… In the off-peak seasons in Sareyn what events are we organizing to consider offering more discounts to attract tourists for these events? …”

4.9.2. Attractions and Complementary Services

“ … The issue of children and related facilities should be seriously addressed. In children’s tourism children play a significant role in parents’ destination choices. For example, in Mashhad extensive advertising has been done for the “Water Waves Land” complex, which is more recognized than Sareyn…”

4.9.3. Competitive Advantages

“ … The geographical location of Sareyn and the presence of therapeutic water in Sareyn distinguish it from other competing destinations in branding the city of Sareyn, in a way that if mineral hot springs were located in tropical areas like the city of Ahvaz (although there are some), their use would not be as desirable due to the hot weather. But because these hot springs are located in the cool climate of Sareyn (cold weather in winter), the use of hot springs is enjoyable…”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alimohamadian, L., & Mostafazadeh, R. (2025). Frequency analysis and trend of maximum wind speed for different return periods in a cold diverse topographical region of Iran. Climate, 13(7), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeyda-Ibáñez, M., & George, B. P. (2017). The evolution of destination branding: A review of branding literature in tourism. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 3(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G., & Kotler, P. (2014). Principles of marketing (15th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, A. S. (2021). Strategic approach to spiritual tourism destination branding development among millennials. In Millennials, spirituality and tourism (pp. 231–251). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E., & Vidić, G. (2024). Choosing the right recovery marketing strategies for future tourism crises: Re-attracting tourists in the post-COVID-19 era. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 72(1), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, N., & Matos, N. (2018). Analysing destination image from a consumer behaviour perspective. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 6(3), 226–236. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S. J., Mattsson, J., & Sørensen, F. (2014). Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: Testing a scale in the tourism context. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, W., & Levy, S. J. (2012). A history of the concept of branding: Practice and theory. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(3), 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2013). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. In Marketing of tourism experiences (pp. 213–229). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B. D. (2018). Co-branding and strategic communication. In L. Liburd, & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collaboration for sustainable tourism development (pp. 35–54). Goodfellow Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S., Roy, S. K., & Tiwari, A. K. (2016). Measuring customer-based place brand equity (CBPBE): An investment attractiveness perspective. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(7), 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., & Gnoth, J. (2011). Visual rhetoric and ethics in marketing of destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M., & Bodeker, G. (2008). Understanding the global spa industry: Spa management. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Maza, F., Ried, A., Odone, C., Le Moigne, J. P., Villalobos, P., & Meneses, K. (2024). Indigenous tourism, crisis and resilience in times of COVID-19: Theoretical and methodological approaches from Chile. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(18), 3001–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shiaty, R. M., Enan, A. M., & Esmail, A. Y. (2023). Branding strategies and ecolodges architecture to develop wellness tourism in Egypt. MSA Engineering Journal, 2(3), 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A., & Garrod, B. (2019). Destination management: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W. C. (2014). Brand equity in a tourism destination. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 10(2), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, A., Piha, L., & Skourtis, G. (2021). Destination branding and co-creation: A service ecosystem perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilanian, S. H., Shadi Dizchi, B., & Ghanbarinejad Esfaghinsari, M. (2011, October 6–8). The effects of electronic business on wellness tourism of Tabriz [Conference presentation]. The First International Conference on Wellness Tourism, Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- Gimechi, S., Mostafazadeh, R., & Alimohamadian, L. (2025). Analysis of extreme precipitation trends and probability distributions across return periods in northwest Iran. Geografický Časopis/Geographical Journal, 77(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M., Haghtalab, N., & Shamshiry, E. (2016). Wellness tourism in Sareyn, Iran: Resources, planning and development. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(11), 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R., Go, F. M., & Kumar, K. (2007). Promoting tourism destination image. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2013). Framing behavioural approaches to understanding and governing sustainable tourism consumption: Beyond neoliberalism, “nudging” and “green growth”? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(7), 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, G. (2009). Managing destination brands: Establishing a theoretical foundation. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(1–2), 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H., Fyall, A., Willis, C., Page, S., Ladkin, A., & Hemingway, A. (2018). Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(16), 1830–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. S., & Meyer, D. F. (2025). Do countries’ environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk ratings influence international tourism demand? A case of the Visegrád Four. Journal of Tourism Futures, 11(1), 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, I., & Todres, L. (2003). The status of method: Flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S. (2016). Let the journey begin (again): The branding of Myanmar. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(4), 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M., Strandberg, C., Oghazi, P., & Mostaghel, R. (2017). The role of destination personality fit in destination branding: Antecedents and outcomes. Psychology & Marketing, 34(12), 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinia, S., Kheirandish, M., Hasanpour, A., & Seidaei, S. R. (2021). The naturalistic model of human capital in the service industry with a qualitative approach. Innovation Management in Defensive Organizations, 4(3), 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jojic, S. (2018). City branding and the tourist gaze: City branding for tourism development. European Journal of Social Science Education and Research, 5(3), 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M., & Ashworth, G. J. (2005). City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(5), 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, S., & Oyner, O. (2021). Wellness tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 76(1), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E., Williams, K. H., & Bordelon, B. M. (2012). The impact of marketing on internal stakeholders in destination branding: The case of a musical city. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(2), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P., Bowen, J. T., Makens, J. C., & Baloglu, S. (2017). Marketing for hospitality and tourism (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, D. G., Kulkarni, G. R., Saurabh, P., & Shome, S. (2025). Health tourism in the era of COVID-19: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. S., Zhang, H., Luo, Y., & Li, Y. (2024). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) measurement in the tourism and hospitality industry: Views from a developing country. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(1), 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandagi, D. W., Indrajit, I., & Wulyatiningsih, T. (2024a). Navigating digital horizons: A systematic review of social media’s role in destination branding. Journal of Enterprise and Development, 6(2), 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandagi, D. W., Soewignyo, T., Kelejan, D. F., & Walone, D. C. (2024b). From a hidden gem to a tourist spot: Examining brand gestalt, tourist attitude, satisfaction and loyalty in Bitung city. International Journal of Tourism Cities, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E., & Capelli, S. (2017). Region brand legitimacy: Towards a participatory approach involving residents of a place. Public Management Review, 19(6), 820–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T., & Slabbert, E. (2024). Destination marketing and domestic tourist satisfaction: The intervening effect of customer-based destination brand equity. Journal of Promotion Management, 30(2), 302–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihardja, E. J., Alisjahbana, S., Agustini, P. M., Sari, D. A. P., & Pardede, T. S. (2023). Forest wellness tourism destination branding for supporting disaster mitigation: A case of Batur UNESCO Global Geopark, Bali. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 11(1), 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraz, M. H., Rabiul, M. K., Adeyinka-Ojo, S., Nair, V., Hasan, M. T., Hossain, M. A., & Jin, H. H. (2025). Digital literacy, marketing ability and tourist healthcare facilities influence tourists’ intention to visit Asian countries through the moderation of AI. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 17(3), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M. R. (2020). Tourism as a livelihood development strategy: A study of Tarapith Temple Town, West Bengal. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 4(3), 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2011). Tourism places, brands, and reputation management. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands (pp. 3–14). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. M. (2019). Marketing and managing tourism destinations (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S. J., Hartwell, H., Johns, N., Fyall, A., Ladkin, A., & Hemingway, A. (2017). Case study: Wellness, tourism and small business development in a UK coastal resort: Public engagement in practice. Tourism Management, 60, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, G., & Mandarić, M. (2020). Challenges in tourist destination branding in Serbia: The case of Prolom Banja. Ekonomika Preduzeća, 68(5–6), 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. (2014). Destination brand performance measurement over time. In N. Kozak, & N. Kozak (Eds.), Tourists’ perceptions and assessments (Vol. 8, pp. 111–120). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainisto, S. K. (2003). Success factors of place marketing: A study of place marketing practices in Northern Europe and The United States [Ph.D. dissertation, Helsinki University of Technology]. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/items/d80d439d-d98f-4c02-b493-d6da2be0dafe (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Ren, C., & Blichfeldt, B. S. (2011). One clear image? Challenging simplicity in place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(4), 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riu, I. A. (2025). Health destination branding strategy: An exploration of digital narratives in promoting medical tourism in Indonesia. International Journal of Humanity Advance, Business & Sciences, 3(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Romão, J., Seal, P. P., Hansen, P., Joseph, S., & Piramanayagam, S. (2022). Stakeholder-based conjoint analysis for branding wellness tourism in Kerala, India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 6(1), 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J. L., Uribe-Toril, J., & Gázquez-Abad, J. C. (2020). Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E., Crespo, C., Moreira, J., & Castanho, R. A. (2022). Brand and competitiveness in health and wellness tourism. In International conference of the international association of cultural and digital tourism (pp. 707–721). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallehn, M., Burmann, C., & Riley, N. (2014). Brand authenticity: Model development and empirical testing. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(3), 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siribowonphitak, C. (2024). Causal relationship model of tourist motivation and destination branding related to behavioral intentions towards health and wellness tourism in Maha Sarakham, Thailand. Asian Administration & Management Review, 6(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, J. R. (2012). Moral economies and commercial imperatives: Food, diets and spas in Central Europe: 1800–1914. Journal of Tourism History, 4(2), 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigel, J., & Frimann, S. (2006). City branding—All smoke, no fire? Nordicom Review, 27(2), 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Šantić, M., & Madžar, D. (2020). Challenges of the branding process of tourist destinations—Tourist destination Herzegovina. Mostariensia: Časopis za Društvene i Humanističke Znanosti, 24(2), 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A. D., & Kozak, M. (2006). Destination brands vs. destination images: Do we know what we mean? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12(4), 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N. H., Dung, H. T., & Tien, N. V. (2019). Branding building for Vietnam tourism industry: Reality and solutions. International Journal of Research in Marketing Management and Sales, 1(2), 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleuberdinova, A., Salauatova, D., & Pratt, S. (2024). Assessing tourism destination competitiveness: The case of Kazakhstan. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 16(2), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N. L., & Rudolf, W. (2022). Social media and destination branding in tourism: A systematic review of the literature. Sustainability, 14(20), 13528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A., & Baloglu, S. (2011). Brand personality of tourist destinations: An application of self-congruity theory. Tourism Management, 32(1), 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasna, S., Wu, W. Y., & Huang, C. H. (2013). The impact of destination source credibility on destination satisfaction: The mediating effects of destination attachment and destination image. Tourism Management, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J. K. (2016). Health, sociability, politics and culture: Spas in history, spas and history: An overview. In Mineral springs resorts in global perspective (pp. 1–14). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, F., Frost, W., & Weiler, B. (2011). Destination brand identity, values, and community: A case study from rural Victoria, Australia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objective | Author, Date | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Presenting a causal relationship model between tourist motivation and health tourism destination branding in Maha Sarakham, Thailand | Siribowonphitak (2024) | Reduced tourist visits due to high tourist motivation |

| Examining the link between branding and competitiveness in health tourism | Santos et al. (2022) | The presence of a significant positive relationship between branding and market share |

| Branding strategies and ecotourism architectures for the development of health tourism in Egypt | El Shiaty et al. (2023) | Enhancing health tourism through sustainable architecture of eco-lodges, providing a matrix for integrating elements of eco-lodge architecture and branding strategy elements |

| Health tourism destination branding (forest) for disaster reduction, Mount Batur UNESCO Global Geopark, Bali | Mihardja et al. (2023) | The positive impact of branding on creating advantages for attractions and recreation in the forest by tourists, local communities, and as a factor in reducing the risk of rock fall. |

| Branding and competition in health tourism. | Tran and Rudolf (2022) | Emphasis on creating and maintaining destination branding in the virtual space, Combining researchers’ contributions in place branding and social media, proposing suggestions for future research |

| Stakeholder-based common analysis for health tourism branding in Kerala, India | Romão et al. (2022) | Developing a stakeholder-based participatory process for collaboration in branding strategy development (including destination inspection through surveys, online analysis to discover the relative importance of health tourism-related features), the necessity of aligning resources with strategic priorities |

| A strategic approach to the development of spiritual tourism destination branding among millennials | Ashton (2021) | Emphasizing the importance of spiritual tourism as part of health tourism, challenges related to the complexity of tourist behavior in selecting and valuing tourism products and services for a richer experience and better quality of life |

| Challenges in the destination tourist branding process: Herzegovina tourism destination | Šantić and Madžar (2020) | Identifying key challenges (ethical, leadership, participation, authenticity, cognitive aesthetics, communication and interaction, digitalization, evaluation) |

| Destination tourism branding challenges in Serbia: Prolom Banja | Perić and Mandarić (2020) | Determining tourists’ perceptions of Prolom Banja and identifying key elements influencing the Prolom Banja brand as a specialized destination in health tourism |

| Examining destination image through consumer behavior. | Baptista and Matos (2018) | Literature review, and presenting the evolution of destination image in destination branding evolution |

| Name | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Gavmishgoli Hot Spring | Located in Sareyn at an altitude of 1940 m above sea level, Gavmishgoli is considered the city’s most abundant mineral spring in terms of water yield and extent. Its slightly acidic, colorless water is recommended for the treatment of various ailments, including chronic rheumatic pains, women’s diseases, and heart conditions |

| Alvars Ski Resort | Nestled in the highlands of Mount Sabalan, 12 km from the Alvars village (a 3000-year-old village) and 24 km from Sareyn city, this ski resort is the largest in the country. Operational for eight months of the year due to snow cover, it features asphalt roads, ski training slopes, two training class stations, a guesthouse, and a restaurant. |

| Golestan Valley (Alvars Valley) | Regarded as one of the most beautiful natural landscapes, Golestan Valley is one of the eastern valleys of the Sabalan region, attracting numerous tourists due to its abundant springs, natural glaciers, lush meadows, and gardens. |

| Gorgor Spring | One of the most famous springs in the Sabalan region, situated in Alvars Valley at an altitude of 2420 m above sea level. |

| Sabalan Spa Complex | As the largest spa complex in the Middle East and Iran, it offers various facilities, including covered pools, Jacuzzis, dry and steam saunas, showers, individual baths, separate medical and therapeutic services for women and men, dedicated parking, and numerous amenities. |

| Vargesaran Waterfall | Located in the verdant foothills of Mount Sabalan, it is considered one of the most pristine attractions in Sareyn. |

| Gharesou Hot Spring | Its water temperature fluctuates in different seasons, reaching 44 degrees Celsius, with a continuous flow on the ground’s surface. |

| Anahita Ancient Hill | Situated in the western part of Sareyn, archaeological excavations have revealed artifacts dating back to the late second and early first millennium BCE. |

| Kanzagh Village | Known for its ancient caves, the old village’s historic district with a chessboard pattern, natural landscapes, and the ruins of the ancient village. |

| Beshbajlar Hot Spring | One of Sareyn’s oldest hot springs, known locally as “Darelar souie,” surrounded by lush meadows and trees, with a water temperature of 35 degrees Celsius. |

| Biledaragh Village (Viladareh) | A tourist attraction located 3 km north of Sareyn, renowned for its landscapes, natural resources such as mineral waters, beautiful valleys with trees and flower-covered meadows, and honeycombs. |

| Ancient Rocky Village of Viand Kalkhouran | A unique village made of stone houses, located 5 km southwest of Sareyn on the Ardabil communication road, representing an exceptional and rare ancient architectural and historical phenomenon in the country. |

| Irdamousi Forest Valley | A beautiful and scenic valley located 14 km west of Ardabil, starting from the vicinity of Sareyn and extending to the village of Nouran, featuring stunning views, rivers and springs, vast meadows, and fruit orchards. |

| Atashgah Village | A historic village known for its ancient hills, temples, old fireplaces, and lush, beautiful nature. |

| No. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Could you discuss the importance of branding in attracting health tourists to Sareyn city? |

| 2 | In your opinion, what are the key elements that make Sareyn a suitable destination for health tourism? |

| 3 | What do you think are the main challenges Sareyn faces in becoming a health tourism brand? |

| 4 | How does Sareyn differentiate itself from its competitors in health tourism branding? |

| 5 | In your view, what is the role of a city’s infrastructure and facilities in becoming a tourism brand? |

| 6 | What actions should the government or relevant institutions take to transform Sareyn into an international health tourism brand? |

| 7 | Are there specific challenges in marketing and advertising the health tourism brand of Sareyn? |

| 8 | How do you analyze the role of sustainable development principles in city branding for health tourism? |

| 9 | How do you see the future path of branding Sareyn as a health tourism destination? |

| No. | Initial Text | Basic Themes | ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mountainous location, hot springs, clean air, cool summer | Suitable geographical location | H1 |

| 2 | Affordable, quality food in Sareyn | Low prices of products | H2 |

| 3 | Scenic villages enabling tourist accommodation | Complementary services | H3 |

| 4 | Recreation planning for different age groups | Creation of complementary recreational attractions | H4 |

| 5 | Weak management, lack of specialist guidance | Poor management | H5 |

| 5a | Necessity of expert input | Necessity of using expert opinions | H6 |

| 6 | Personal/short-term priorities over long-term planning | Long-term planning necessity | H7 |

| 6a | Need for comparative studies | Conducting comparative studies | H8 |

| 7 | Underuse of media for tourism promotion | Inadequate advertising | H9 |

| 8 | Lack of multi-day stay planning, missing specialized medical centers | Establishment of complementary therapeutic attractions | H10 |

| 9 | Failure to attract investments | Need for attracting investment | H11 |

| 10 | Lack of city-level facilities (toilets, maps, multilingual pricing) | Requirement for appropriate urban services | H12 |

| 11 | Weak transportation and healthcare infrastructure | Weakness in infrastructure | H13 |

| 12 | Presence of natural mineral waters | Natural mineral waters | H14 |

| 13 | Need for complementary/recreational and tech-based tourism | Necessity of providing complementary services | H15 |

| 14 | Close to Tabriz as medical hub | Proximity to Tabriz | H16 |

| 15 | Develop communication infrastructure | Investment in infrastructure | H17 |

| 16 | Coordination among institutions | Establishment of collaboration networks | H18 |

| 17 | Privatize tourism management | Creating opportunities for private sector | H19 |

| 18 | Organize tourism calendar | Necessity of preparing a tourism calendar | H20 |

| 19 | Friendly foreign relations for tourists | Improving foreign policy | H21 |

| 20 | Specialized health tourism courses at university | Establishment of specialized university courses | H22 |

| 21 | Special investment privileges (banking) | Facilitating investment | H23 |

| 22 | Tourism insurance for foreign tourists | Offering tourism insurance | H24 |

| 23 | Investment in medical therapies | Investment in complementary services | H25 |

| 24 | Flight routes from Ardabil | Strengthening aviation infrastructure | H26 |

| 25 | Scientific certification of mineral waters | Necessity of studies on mineral waters | H27 |

| Basic Theme | Code | Basic Theme | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak air transport | M1A39, M3C35, M3C36, M3C37, M3C38, M3C39, M5E26, M5E27, M5E28, M5E30, M6F28, M6F29, M6F30, M8H26, M13M10, M15O7, | Stakeholder cooperation | M4D36, |

| Limited accessibility | M3C12, M3C13, M3C14, M6F32, M8H13, M10J6, M15O7, | Stakeholder interactions | M6F39, |

| No rail services | M3C40, M5F29, M5F31, M10I11, M13M11,M15O8, | Networking | M3C56, M8H18, M13M14, |

| Low-quality hotels | M1A35, M1A65, M3C18, M10J8, M12L8, M13M12, | Water management | M18R12, |

| Inadequate insurance | M8H24, | Health and sustainability | M3C52, |

| Poor hospitals | M5E41, M5E42, M6F33, M6F40, | Sustainability principles | M1A81, M1A83, M4D54, M9I18, M10J22, M11K11, M13M22, M15O16, M16P12, M17Q15, M18R12, |

| Poor info dissemination | M1A31, M1A32, M7G2, | Waste management | M6F41, |

| Weak content production | M1A15, M1A18, M1A45, M1A46, M1A47, M1A87, M3C47, M12L2, M15O15, | Private sector advertising | M6F45, |

| Lack of awareness | M2B29, M9I4, M10J17, | Off-season discounts | M3C48, M5E17, |

| Government interference | M11K9, | Customer-friendly services | M1A53, |

| Bad foreign policy | M8H21, | Increase events | M5E18, M14N5, |

| No comprehensive plan | M6F44, M13M11, M13M15, | Brand image | M13M1, M15O1, M17Q1, |

| Poor planning | M1A86, M4D8, M4D16, M4D19, M4D25, M4D28,M6F43, M8H7, M12L13, M13M2, M14O18, M18R8, | Service differentiation | M3C2, M7G3, |

| Bureaucracy | M2B32, | Marketing mix adherence | M3C3, |

| Tourist distrust | M10J20, M13M18, | Direct marketing | M3C30, M3C50, |

| Weak HR training oversight | M3C46, M10J3, | Targeted marketing | M16P2, |

| Ideological perspective | M10J5, | Assess health tourist needs | M1A26, M1A55, |

| Rapid hydrotherapy growth | M11K1, | Intl. connections | M17Q10, |

| Weak supervision over services | M10J19, M10J21, | Info tours | M5E19, M5E36, |

| Short-term planning | M4D29, | Target market ID | M3C51, |

| Neglect land-use | M6F49, | Brand positioning | M7G1, |

| Lack of integration studies | M4D4, M4D33, | Specialized marketers | M7G17, |

| No specialized studies | M4D5, M5E12, M13M7, M13M23, | Domestic and intl. market ID | M2B4, M2B5, M3C50, M3C51, M16P9, |

| No competitive advantage ID | M1A50, M6F6, M13M24, | Carrying capacity | M1A84, M17Q7, |

| No comparative studies | M8H8, M13M9, | Complementary attractions | M1A22, M1A52, M6F14, M7G11, M8H4, M8H10, M11K12, |

| Specialized agencies | M18R3, | Food quality | M7G20, |

| Specialist doctors | M1A29, M1A30, M11K3, | Standard services | M16P14, |

| Skilled HR | M4D51, M10J3, M10J10, M11K4, M12L9, M14N7,M15O10, M16P11, | Investment in attractions | M15O4, |

| Specialized tour guides | M7G14, | Investment in supplementary services | M8H25, M10I12, M11K2, M13M13, |

| Business facilitation | M3C41, | Organic food | M17Q5, |

| Adequate budget | M4D48, M17Q9, R18R10, | Suitable climate | M3C9, M5E5, M6F5, M7G10, M10I2, M14N2, M17Q2, |

| Private sector investment | M4D49, M6F38, | Mineral springs | M2B24, M10I1, |

| Investment incentives | M1A70, M2B31, M8H23, M18R9, | Medicinal plants | M6F27, M14N3, M17Q4, |

| University-industry collab | M3C57, | - | - |

| Basic Themes | Organizing Themes |

|---|---|

| Air transportation weakness | Infrastructure Challenges |

| Accessibility issues | |

| Absence of trains | |

| Low quality of hotels | |

| Poor insurance | |

| Poor hospital infrastructure | |

| Poor information dissemination | Marketing Challenges |

| Content production deficiency | |

| Ignorance | Governance Challenges |

| Government intervention | |

| Inappropriate foreign policies | |

| Lack of comprehensive plans | |

| Weak planning | |

| Bureaucracy | |

| Tourist distrust | |

| Lack of oversight on human resources training | |

| Ideological viewpoint | |

| Heterogeneous growth of SPA complex | |

| Lack of supervision on the provision of tourism services | |

| Short-term planning | |

| Neglect of land-use planning | |

| Lack of integration among conducted studies | Research Challenges |

| Absence of specialized studies | |

| Failure to identify competitive advantages | |

| Lack of comparative studies | |

| Specialized agency | Human resource Challenges |

| Specialized physician | |

| Specialized human resources | |

| Expert tour leader | |

| Facilitation of the business environment | Investment Challenges |

| Adequate budget | |

| Private sector investment | |

| Investment incentives | |

| University-industry collaboration | Networking Challenges |

| Stakeholder cooperation | |

| Stakeholder interactions | |

| Networking | |

| Water management | Sustainable Development challenges |

| Health within sustainable development | |

| Adherence to sustainable development aspects | |

| Waste management |

| Side Factor | Global Theme |

|---|---|

| Private sector advertising expenditure allocation | The Necessity of Marketing |

| Providing discounts during the off-peak tourist season | |

| Providing customer-friendly services | |

| Increasing the frequency of events | |

| Creating a brand image | |

| Creating differentiation in services | |

| Adherence to integrated marketing principles | |

| Direct marketing | |

| Targeted marketing | |

| Investigation of health tourist needs | |

| Establishing communication with international companies | |

| Holding info tours | |

| Identifying target markets | |

| Brand positioning | |

| Necessity of employing specialized marketers | |

| Necessity of identifying domestic and international markets | |

| Necessity of considering carrying capacity | |

| Complementary attractions | Attraction Complementary Services |

| Increasing quality of food products | |

| Necessity of providing standard services | |

| Investment in complementary attractions | |

| Investment in complementary services | |

| Organic food | Geographical Advantages |

| Suitable weather | |

| Hot Mineral springs | |

| Medicinal plants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mostafazadeh, R.; Madani, J.; Nemati, V.; Aghvami Moghadam, P. Factors Influencing Geothermal-Based Health Tourism Development: A Thematic Analysis in Natural Hot Spring Destinations of Northwest Iran. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040189

Mostafazadeh R, Madani J, Nemati V, Aghvami Moghadam P. Factors Influencing Geothermal-Based Health Tourism Development: A Thematic Analysis in Natural Hot Spring Destinations of Northwest Iran. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040189

Chicago/Turabian StyleMostafazadeh, Raoof, Javad Madani, Vali Nemati, and Pooneh Aghvami Moghadam. 2025. "Factors Influencing Geothermal-Based Health Tourism Development: A Thematic Analysis in Natural Hot Spring Destinations of Northwest Iran" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040189

APA StyleMostafazadeh, R., Madani, J., Nemati, V., & Aghvami Moghadam, P. (2025). Factors Influencing Geothermal-Based Health Tourism Development: A Thematic Analysis in Natural Hot Spring Destinations of Northwest Iran. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040189