Spatial Justice and Post-Development Perspectives on Community-Based Tourism: Investment Disparities and Climate-Induced Migration in Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Questions

- In what ways do the distribution and flexibility of donor investments contribute to regional disparities in CBT readiness—particularly the privileging of the Mekong Delta over Northern ethnic minority regions?

- How do spatial justice and post-development perspectives help explain why donor priorities reinforce structural inequalities rather than alleviating them?

- How does the epistemic visibility of CBT scholarship follow donor concentration, and what strategies (e.g., participatory or field-based research) could better represent marginalized communities in the Northern Highlands?

2.3. Research Aims

2.4. Data Sources and Collection

Search Strategy/Data Handling

2.5. Methodology: Theoretical Framing

2.6. Regional Investment Categorization and Funding Analysis

3. Literature Review: Spatial Justice and Post-Development Critique

3.1. Spatial Justice and Development Disparities

3.2. Post-Development Critique and Community Agency

3.3. Integrative Framework for CBT in Vietnam

3.4. Contextual Background: Vietnam’s Regional Landscape for CBT

3.4.1. Mekong Delta (Southern Vietnam)

3.4.2. Central Vietnam

3.4.3. Northern Highlands

4. Results

4.1. Financial and Infrastructure Investments

4.2. Macro vs. Micro-Level Funding Strategies: Implications for Equity

4.3. IFAD’s Targeted Funding Strategy and Spatial Equity Implications

4.4. Macro-Level Donor Investment Patterns: Centralization and Corridor Bias

4.5. Regional Development Barriers and Spatial Disparities in CBT Readiness

4.6. Ethnicity, Poverty, and Structural Exclusion

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Practical Implication: Spatial Disparities in CBT Access and Implementation

- Pair WB/ADB corridor projects with ring-fenced CBT readiness packages (training, market access, seed finance) in Ha Giang, Dien Bien, Cao Bang.

- Create co-finance windows where IFAD/NGOs deliver last-mile empowerment inside macro projects.

- Require province-level budget disclosure and annual spatial-equity scorecards.

- Add ethnic-inclusion indicators (co-design, revenue sharing, local governance roles) to donor log-frames.

- Fund participatory marketing & cultural heritage stewardship alongside infrastructure.

5.3. Epistemic Visibility and Development Narratives

5.4. Ethnicity, Poverty, and NGO Engagement in Structural Exclusion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| CBT | Community-Based Tourism |

| CSAT | Climate-Smart Agriculture Transformation Project |

| CSSP | Commercial Smallholder Support Project |

| DBRP | Developing Business with the Rural Poor |

| DPRPR | Decentralized Programme for Rural Poverty Reduction |

| 3EM | Economic Empowerment of Ethnic Minorities |

| 3PAD | Pro-Poor Partnerships for Agro-Forestry Development |

| GIZ | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (German Agency for International Cooperation) |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agricultural Development |

| IFIA | Innovative Financial Incentives for Adaptation |

| IMPP | Improving Market Participation of the Poor |

| IOM | International Organization for Migration |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| LLM | Large Language Model (subset of AI, leveraging machine learning) |

| MD-ICRSL | Mekong Delta-Integrated Climate Resilience and Sustainable Livelihoods Project |

| RIDP | Rural Income Diversification Project |

| Resolution 08-NQ/TW | A key Vietnamese governmental tourism policy resolution issued on 16 January 2017 |

| SES | Social Ecological Systems–Resilience Theory |

| TNSP | Tam Nong Support Project for Poor Rural Areas |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Program |

| WB | World Bank |

Appendix A

| Theory | Core Concepts | Strengths for CBT Research | Weaknesses/Critiques | Application to Vietnam CBT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience Theory (Holling, 1973; Folke, 2006) | Adaptive capacity of socio-ecological systems; ability to absorb shocks and reorganize. | Explains how communities adjust livelihoods to climate change and migration pressures. | Risks treating adaptation as technical; overlooks power inequalities and structural drivers of vulnerability. | Explains why Mekong Delta households diversify into CBT after climate shocks. |

| Sustainability/SES Framework (Ostrom, 2009) | Integration of ecological integrity, institutional adaptability, and collective action. | Emphasizes balance between environment, economy, and governance; widely applied in tourism. | May depoliticize structural inequality; assumes institutions can adapt inclusively. | Useful for evaluating how local rules, land use, and CBT enterprises interact. |

| Spatial Justice (Soja, 2010; Lefebvre, 1974/1991) | Justice is inherently spatial; resource allocation and opportunity distribution shaped by geography. | Highlights unequal distribution of tourism infrastructure and donor funding. | Less focused on cultural or epistemic dimensions of exclusion. | Reveals why Mekong provinces attract more CBT funding while Northern Highlands are marginalized. |

| Post-Development Critique (Escobar, 1995; Sachs, 1992) | Development is a discursive construct; questions whose knowledge and priorities shape interventions. | Challenges donor-driven, top-down CBT models; re-centers local agency and indigenous knowledge. | Sometimes criticized for romanticizing localism or rejecting modernity. | Explains why Northern ethnic groups receive only poverty projects, not CBT-specific investments. |

| NGO/Project | Region/Communities | Core Activities | Outcomes/Contributions | Limitations/Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action on Poverty (AoP) | Da Bac, Hoa Binh Province (ethnic minority communities) | Developed CBT homestay model; capacity-building; micro-loans; mentorship for local entrepreneurs. | Strengthened community participation; created a model of culturally grounded CBT. | Limited visibility in academic literature; dependent on donor alignment for funding legitimacy. |

| Streets International | Hội An (urban disadvantaged youth) | Vocational training in hospitality and culinary arts; integrated graduates into the tourism economy. | Provided pathways for marginalized youth to benefit from tourism growth. | Not explicitly CBT; limited reach beyond one urban center. |

| Improving Market Participation of the Poor (IMPP)—IFAD | Ha Tinh and Tra Vinh Provinces | Collaboration with provincial governments, cooperatives, and CBOs to strengthen livelihoods and market access. | Enhanced household income, governance, and community resilience; promoted participatory development. | NGOs not always explicitly named; engagement mediated through CBOs and government structures. |

| 1 | The term Global South is used here not in a strictly geographical sense but as a socio-political category referring to countries historically shaped by colonial extraction and currently disadvantaged within global economic and environmental systems (Dados & Connell, 2012). |

References

- Action on Poverty (AoP). (n.d.). Community-based tourism initiatives in Vietnam. Action on Poverty. Available online: https://actiononpoverty.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Asian Development Bank. (2023). Vietnam: Projects and results. Available online: https://www.adb.org/where-we-work/viet-nam/projects-results (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Baulch, B., Chuyen, T. K., Haughton, D., & Haughton, J. (2009). Ethnic minority poverty in Vietnam. (Policy Research Working Paper No. 4850). World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/4046 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Bebbington, A. (2000). Reencountering development: Livelihood transitions and place transformations in the Andes. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(3), 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K., & Westaway, E. (2011). Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: Lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36(1), 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi Thai, H. A. (2017, August 1–2). Community involvement in developing community-based tourism: A case study of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The Tenth Vietnam Economist Annual Meeting Conference, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Available online: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/369448974_Community_Involvement_in_Developing_Community-Based_Tourism_A_Case_Study_of_Vietnam%27s_Central_Highlands (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Cong, T. T., & Thu, N. T. (2020). Challenges in tourism entrepreneurship in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Conga, V. T., & Chip, N. H. (2020). Tourism diversification and agro-based livelihoods in Quang Nam Province. Vietnam Journal of Tourism Research, 10(2), 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dados, N., & Connell, R. (2012). The Global South. Contexts, 11(1), 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeç, M. (2001). Justice and the spatial imagination. Environment and Planning A, 33(10), 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. X. (2025). Evaluation of the potential for community-based tourism development in Tra On district, Vinh Long province. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 8(4), 2715–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. X., Nguyen, T. L., & Le, H. T. (2023). Community readiness for tourism development in Northern Vietnam: A multidimensional assessment. Journal of Tourism and Development Studies, 15(2), 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the Third World. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2021). Farmer field schools for sustainable agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Gao, T., Phan, L. H., & Tran, T. P. (2021). Tourism, pollution, and public health concerns in Southern Vietnam: A cross-sectional analysis. Environmental Research in Asia, 7(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Garschagen, M., Diez, J. R., & Nhan, D. K. (2011). Socio-economic development in the Mekong Delta: Between the prospects for progress and the realms of reality. In G. Waibel, J. Ehlert, & H. Feuer (Eds.), Southeast Asia and the civil society gaze: Scoping a contested concept in Cambodia and Vietnam (pp. 161–182). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. (2023). Statistical yearbook of Vietnam 2022. General Statistics Office. Available online: https://www.nso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2023/06/statistical-yearbook-of-2022 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Helvetas. (2020). Sustainable agriculture and tourism linkages in Northern Vietnam. Helvetas Vietnam. Available online: https://vietnam.helvetas.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Ho, X. L., & Nguyen, Q. V. (2025). Assessment of influencing factors and development directions for economic growth through community-based tourism of ethnic minorities: A case study of Dien Bien and Cao Bang, Vietnam. International Journal of Geoheritage & Parks, Advance online publication. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5087370 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hoang, T. V., Le, D. N., & Pham, M. H. (2018). Infrastructure limitations and tourism constraints in ethnic minority areas of Northern Vietnam. Asian Tourism Studies, 10(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L. P., Ngo, H. T., & Pham, L. T. (2021). Community-based tourism: Opportunities and challenges: A case study in Thanh Ha Pottery village, Hoi An city, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 7, 1926100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, L. T. M., Dang, T. M., & Tran, Q. T. (2020). Tourism and social vulnerability in peri-urban Mekong communities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(6), 645–659. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, P. T., & Lee, J. H. (2017). Financial literacy and entrepreneurial capacity in Vietnam’s rural north. Journal of Development and Policy Review, 19(2), 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD. (2012). Country programme evaluation: Socialist Republic of Viet Nam country programme evaluation, report No. 2606-VN, May 2012, independent office of evaluation of IFAD. Available online: https://webapps.ifad.org/members/ec/71/docs/EC-2012-71-W-P-4-Rev-1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- IFAD. (2022). Decentralized programme for rural poverty reduction (DPRPR) and improving market participation of the poor (IMPP). International Fund for Agricultural Development. Available online: https://www.ifad.org (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- IFAD. (2023a). Annual report on the independent evaluation of IFAD: Pro-poor value chain and knowledge integration. Available online: https://webapps.ifad.org/members/eb/139/docs/EB-2023-139-R-13.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- International Fund for Agricultural Development. (2023b). IFAD in Vietnam: Investing in rural people. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/w/country/viet_nam (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- JICA. (2024). JICA in Vietnam: Supporting inclusive and sustainable development. Japan International Cooperation Agency. Available online: https://www.jica.go.jp/vietnam/english/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Khantee, N., & Jeerapattanatorn, P. (2023). Current evidence on tourism problems and entrepreneurship development in Vietnam: A systematic review. International Research and Review, 13(1), 44–74. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1432614.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Kunjuraman, V. (2022). Community-based tourism and climate change adaptation: A conceptual perspective. In R. Nair, K. K. Bhuiyan, & N. A. Mohamed (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable tourism and hotel operations in global hypercompetition (pp. 105–120). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Lacitignola, D., Petrosillo, I., Cataldi, M., & Zurlini, G. (2007). Modelling socio-ecological tourism-based systems for sustainability: A case study. Ecological Modelling, 206(1–2), 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S. T., & Vo, C. D. (2020). Livelihood vulnerability and adaptation capacity of rice farmers under climate change and environmental pressure on the Vietnam Mekong Delta floodplains. Water, 12(11), 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., Nguyen, M. T., & Do, Q. N. (2020). Social impacts of tourism in Vietnam’s rural delta regions. Tourism and Society, 9(3), 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell. (Original work published 1974). [Google Scholar]

- Luan, D. X., Hai, T. M., An, D. H., & Thuy, P. T. (2023). Transformation of heritage into assets for income enhancement: Access to bank credit for Vietnamese community-based tourism homestays. International Journal of Rural Management, 19(3), 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, N. T., Bui, T. H., & Nguyen, T. M. (2014). Environmental challenges and tourism infrastructure in upland Vietnam. Sustainable Environment Journal, 12(3), 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D. T., & Naff, D. B. (2024). The Ethics of Using Artificial Intelligence in Qualitative Research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 19(3), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P. (2004). Becoming socialist or becoming Kinh? Government policies for ethnic minorities in the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. In C. R. Duncan (Ed.), Civilizing the margins: Southeast Asian government policies for the development of minorities (pp. 182–213). Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mekong Delta Development Research Institute (MDI), Can Tho University. (2022). Training programs in rural and agricultural development for local stakeholders. Mekong Delta Development Research Institute. Available online: https://mdi.ctu.edu.vn/en/education (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Mekong Plus. (2023, December 26). The state of NGOs in Vietnam in 2023: Challenges and limitations. Available online: http://mekongplus.org/en/2023/12/26/the-state-of-ngos-in-vietnam-in-2023 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Michaud, J. (2016). Historical dictionary of the peoples of the Southeast Asian massif. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture, Sports & Tourism. (2016). Recognition of national intangible cultural heritage: Cái Răng floating market. Government of Vietnam.

- Ngo, T., Hales, R., & Lohmann, G. (2018). Collaborative marketing for the sustainable development of community-based tourism enterprises: A reconciliation of diverse perspectives. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(18), 2266–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. D., & Do, A. T. (2024). Developing community-based tourism towards circular economy in Ha Giang Province, Vietnam. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Management (IJAEM), 6(2), 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K. T., Murphy, L., Chen, T., & Pearce, P. L. (2023). Let’s listen: The voices of ethnic villagers in identifying host–tourist interaction issues in the Central Highlands, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 19(2), 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., Le, D. B., Dang, V. H., Vu, H. L., & Hoang, X. T. (2010). Inequality, poverty, and ethnic minorities in Vietnam. (CPRC Working Paper No. 10). Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC). Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/127305/CPR2_Background_Papers_Nguyen-Le_Dang-Vu_Hoang.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Nguyen, T. H., Le, D. T., & Tran, H. M. (2023). Community-based tourism development and cultural heritage in Central Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality Journal, 18(2), 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. H., Le, T. V., & Vu, H. T. (2021). COVID-19 and the restructuring of tourism supply chains in Southern Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism Recovery, 12(4), 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. H. P. (2017). The development of Cái Răng floating market tourism in Can Tho city: From policy to practice. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 12(3), 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Y. C., Anh, N. T. N., Thanh, H. C. T., Vy, T. T., & Truong, D. T. (2025). Eco-tourism development in Can Tho City: Current situation and solutions. Vietnam Journal of Science and Technology, Can Tho Technical & Technology University Journal, VJOL. Available online: https://vjol.info.vn/index.php/tcdaihockythuatcongngheCanTho/article/view/109032 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- OECD. (2019). Development co-operation report 2019: A fairer, greener, safer tomorrow. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325(5939), 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxfam. (2019). Inclusive markets and livelihoods in Vietnam. Oxfam Vietnam. Available online: https://vietnam.oxfam.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Pham, V. Q. (2020). Tourism and socio-environmental transformation in the Mekong Delta. Vietnam Journal of Environmental Studies, 32(1), 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T. T., Nguyen, L. T., & Do, H. Q. (2021). Water insecurity and freshwater scarcity in Northern Vietnamese communities. Journal of Environmental Sustainability, 19(4), 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Phu, T. V., & Thi Thu, H. N. (2022). Cultural misunderstandings in tourism: A case study in Central Vietnam. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(4), 312–328. [Google Scholar]

- Phuong, N. T. M., Song, N. V., & Quang, T. X. (2020). Factors affecting community-based tourism development and environmental protection: Practical study in Vietnam. Journal of Environmental Protection, 11(2), 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelma, T., Bayrak, M. M., Nha, D., & Tran, T. A. (2021). Climate change and livelihood resilience capacities in the Mekong Delta: A case study on the transition to rice–shrimp farming in Vietnam’s Kien Giang Province. Climatic Change, 164(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. X., Nguyen, H. D., & Le, M. T. (2023). Post-pandemic tourism recovery and sustainability in Southern Vietnam. Tourism Economics and Development Review, 11(2), 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Quang, T. X., Phuong, N. T. M., & Linh, D. T. (2022). Environmental challenges and tourism readiness in coastal villages of central Vietnam. Sustainable Tourism Perspectives, 9(3), 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Quyen, N. T., & Tuan, P. V. (2022). Gendered barriers in tourism entrepreneurship: A case study from the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Journal of Tourism and Gender Studies, 5(1), 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, W. (Ed.). (1992). The development dictionary: A guide to knowledge as power. Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- SNV Netherlands Development Organisation. (2017). Sustainable tourism and pro-poor value chains in Vietnam. SNV. Available online: https://snv.org/country/vietnam (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Soja, E. W. (2010). Seeking spatial justice. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Streets International. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.streetsinternational.org/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Suntikul, W., Pratt, S., I Kuan, W., Wong, C. I., Chan, C. C., Choi, W. L., & Chong, O. F. (2016). Impacts of tourism on the quality of life of local residents in Hue, Vietnam. Anatolia, 27(4), 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. (2015). Strategic flexibility: The evolving paradigm of strategic management. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 16(2), 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The British Academy. (n.d.). Outdoor tourism and the changing cultural narratives in Vietnamese ethnic minority communities. Available online: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/projects/outdoor-tourism-and-the-changing-cultural-narratives-in-vietnamese-ethnic-minority-communities/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Tran, T. A., Tran, D. D., Van Vo, O., Pham, V. H. T., Tran, H. V., Yong, M. L., Le, P. V., & Dang, P. T. (2024). Evolving pathways towards water security in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: An adaptive management perspective. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 54(3), 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, T. T., & Ryan, C. (2015). Heritage and cultural tourism: Exploring the potential in Hue, Vietnam. Tourism Management Perspectives, 14, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V. D. (2017). Tourism, poverty alleviation, and the informal economy: The street vendors of Hanoi, Vietnam. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. (2023). Vietnam: Climate resilience and community-based tourism. United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.vn.undp.org/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- UNDP & World Bank. (2009). Baseline surveys (2007–2008) on extremely disadvantaged communes: Poverty headcounts exceeding 80% for ethnic minorities (Mông, Dao, et al.). United Nations Development Programme & World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- VietnamPlus. (2023). WB, ADB provide loans, grants for three projects in Vietnam. Available online: https://en.vietnamplus.vn (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- VietnamPlus. (2025, April). WB, ADB provide loans, grants for three projects in Vietnam. VietnamPlus. Available online: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/wb-adb-provide-loans-grants-for-three-projects-in-vietnam-post317537.vnp?utm_source (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- World Bank. (2016). Mekong delta integrated climate resilience and sustainable livelihoods project: Project appraisal document. Available online: https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P153544 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- World Bank. (2020a). Community-based tourism and infrastructure development. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- World Bank. (2020b). Mobilizing financing for climate-smart investments in the Mekong delta: An options note. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- World Bank. (2022a). Vietnam poverty and equity assessment. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099115004242216918/pdf/P176261155e1805e1bd6e14287197d61965ce02eb562.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- World Bank. (2022b). Mekong delta transport infrastructure development project: Beneficiary impact assessment. (Implementation Completion Report). Available online: https://mdri.org.vn/projects/mekong-delta-transport-infrastructure-development-project-beneficiary-impact-assessment-2/?utm_source (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- World Bank. (2022c). Vietnam country overview. World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- World Bank. (2023). Vietnam: Country partnership framework. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- World Bank. (2025). Vietnam—WBG finances. (country summary as of June 2025). World Bank Country Data Portal. Available online: https://financesone.worldbank.org/countries/vietnam?utm_source (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Ziai, A. (2007). Exploring post-development: Theory and practice, problems and perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S., Jeong, Y. J., & Milano Batista, C. (2020). Factors that influence community-based tourism (CBT) in developing and developed countries: A directed content analysis of case studies. Tourism Geographies, 23(5–6), 1040–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Investment Focus | Total Amount Invested (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank | Large-scale infrastructure, economic integration, climate resilience | US $25.9 Billion |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | Transport infrastructure, clean energy, vocational training, rural development, climate resilience | US $18 Billion |

| IFAD | Small-scale rural infrastructure, livelihood diversification, community-led empowerment | US $788 Million |

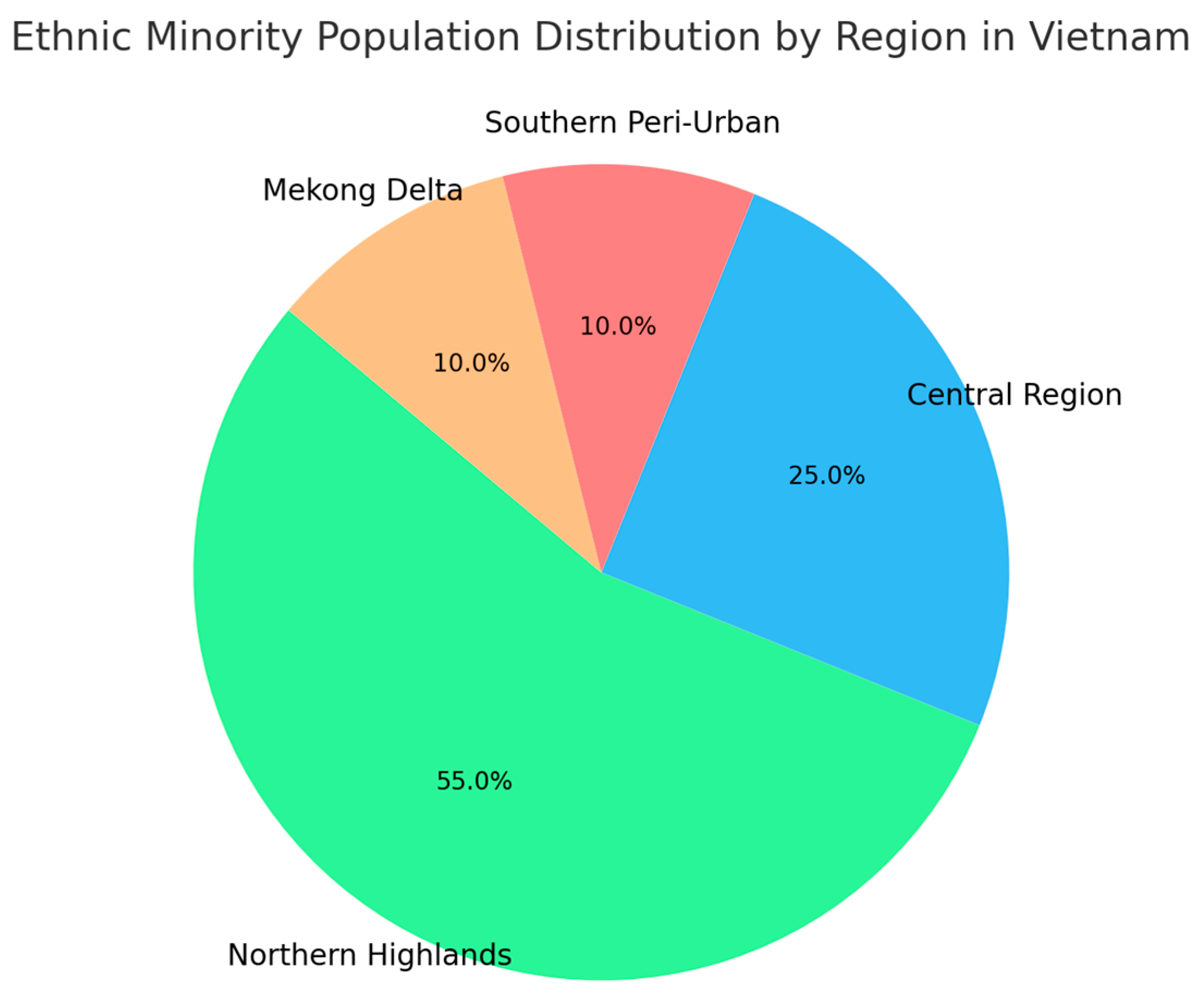

| Region | Percentage % | Amount (Million USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Mekong Delta (Southern) | 40 | 168.20 |

| Central Vietnam | 22.2 | 97.56 |

| Northern Highlands | 23.8 | 87.46 |

| Southern Peri-urban/Urban | 14.0 | 67.28 |

| Region (with Locations) | Percentage % | Funding Amount (Million USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Mekong Delta (Can Tho, Ben tre) | 56.5 | 560 |

| Central Vietnam (Hue, Da Nang) | 23.4 | 232 |

| Northern Highlands (Ha Giang, Dien Bien) | 5.0 | 50 |

| National or Multi-regional | 15.1 | 150 |

| Regional Needs (Common Problems) | IFAD’s Common Project Investments |

|---|---|

| Limited entrepreneurship skills and inadequate infrastructure across all regions | Entrepreneurship support, rural enterprise development, basic infrastructure investment (IMPP, DBRP, DPRPR) |

| Region | Region-Specific Needs | IFAD’s Region-Specific Investments |

|---|---|---|

| Northern Highlands | Freshwater shortage, financial literacy gaps, minority empowerment, negative perceptions of local tourism activities (street vending) | Infrastructure enhancement, ethnic minority empowerment, market integration, rural enterprise support (DPRPR, 3EM, DBRP) |

| Central Vietnam | Cultural misunderstandings, insufficient promotion of cultural heritage, inadequate facilities, environmental sustainability concerns, agro-economic competition | Agro-forestry development, sustainable agricultural practices, poverty alleviation for ethnic minorities (3PAD, TNSP) |

| Mekong Delta & Southern Peri-Urban | Gender-based pressures, ineffective marketing, socio-economic challenges (pollution, increased living costs, social issues), vulnerability to climate impacts | Market access enhancement, rural enterprise and eco-tourism development, climate adaptation and mangrove-based innovations (IMPP, DBRP, IFIA, CSAT) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyun, H. Spatial Justice and Post-Development Perspectives on Community-Based Tourism: Investment Disparities and Climate-Induced Migration in Vietnam. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040188

Hyun H. Spatial Justice and Post-Development Perspectives on Community-Based Tourism: Investment Disparities and Climate-Induced Migration in Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040188

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyun, Hanna. 2025. "Spatial Justice and Post-Development Perspectives on Community-Based Tourism: Investment Disparities and Climate-Induced Migration in Vietnam" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040188

APA StyleHyun, H. (2025). Spatial Justice and Post-Development Perspectives on Community-Based Tourism: Investment Disparities and Climate-Induced Migration in Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040188