1. Introduction

Inclusive creative tourism is an important strategy for rural development and social inclusion. By blending local culture with artistic expression, it generates economic opportunities while nurturing social cohesion. In rural Indonesia, where structural inequalities persist, this model offers pathways to integrate marginalised groups into wider socio economic networks. Collective action grounded in community social capital shared trust, dense networks, and cooperative norms underpins sustainable tourism development (

Auliah et al., 2025). Strong communal ties and trust can drive inclusive tourism practices that enhance both economic viability and social integration, echoing (

Wartecka-Wazynska, 2021) who found that rural tourism reinforces local identity and social capital.

Yet, the full social inclusion of individuals with intellectual disabilities remains elusive. They face infrastructural barriers, limited tailored services, and persistent stigma challenges that are amplified in rural destinations with scarce resources. Although social capital can mobilise collective action, it may still leave participation gaps for vulnerable groups (

Hwang & Stewart, 2017). These constraints demand targeted, provider-side interventions that many rural tourism strategies still lack (

Sica et al., 2020).

Globally, community-based tourism has been invigorated by creative industries, which balance heritage preservation with economic empowerment. By tapping local artistic talent in handicrafts, performance arts, and visual design, these ventures draw visitors and strengthen community livelihoods.

Gray et al. (

2018) show that community-based sustainable business models enhance economic resilience and help maintain social and cultural values in resource-constrained contexts. The art–tourism synergy diversifies income and embeds authenticity in visitor narratives, broadening market appeal and improving socio economic prospects in underdeveloped rural areas (

Yi et al., 2022).

Social capital is a cornerstone of collaborative and inclusive innovation. Through networks, shared norms, and trust, it enables residents to co-create tourism strategies that mirror community values (

Zhang et al., 2021). Prior studies demonstrate that social capital facilitates cooperation, reinforces shared identity, and bridges disparities, making it indispensable for inclusive tourism. Communities with strong social capital are better able to initiate, adapt, and sustain tourism programmes for diverse stakeholders, and they show higher resilience and innovation (

Sukaris, 2024).

Participatory, art-based activities empower marginalised groups, including individuals with intellectual disabilities. Besides preserving cultural identity, they open pathways to social recognition and economic independence. Community engagement in the arts can transform local attitudes and deepen investment in inclusive tourism (

Zhou et al., 2024). Initiatives such as

Batik Ciprat enable disabled artisans to showcase their talents and earn income, thereby enhancing dignity, reducing stigma, and diversifying the rural economy (

Prayitno et al., 2019).

Despite advances, significant barriers persist. Inadequate infrastructure, limited political will, and entrenched stigma still restrict the full participation of marginalised groups. Although inclusive tourism principles are informing government accessibility reforms, gaps between policy and practice remain (

Hamdani et al., 2023). Bureaucratic inertia and poor stakeholder coordination continue to impede progress toward universal design and meaningful inclusion (

Raveendran, 2024). This highlights the need for locally grounded innovations that complement national policies.

This study examines the transformative potential of Batik Ciprat as a vehicle for inclusive creative tourism in Karangpatihan Village, Indonesia. Intellectually disabled artisans produce expressive batik that now anchors the village’s tourism identity. Combining qualitative fieldwork with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (SEM-PLS), this research analyses how social capital dimensions—trust, networks, and inclusive norms—shape empowerment, tourism participation, and quality-of-life outcomes. By presenting a replicable model of inclusive rural tourism, this study advances discourse on accessible tourism and aligns with global sustainable development goals. Specifically, this paper seeks to answer three research questions: (RQ1) How do social capital dimensions empower individuals with intellectual disabilities in creative tourism? (RQ2) In what ways do family support and individual capacity interact with community involvement to enhance quality of life? (RQ3) How does Batik Ciprat function as a branding identity for inclusive rural tourism at the village level?

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs qualitatively led mixed-methods, sequential exploratory design that combines a qualitative case study with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine how

Batik Ciprat fosters inclusive creative tourism in Karangpatihan Village. This research aims to understand how social capital manifested in networks, trust, and inclusive norms can empower individuals with intellectual disabilities to participate in and shape local tourism practices. This methodological approach is particularly suited to uncovering both the depth of lived experiences and the structure of causal relationships in community-based tourism interventions. The analysis used in this research is confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The results of this research indicate that the factors that form social capital have the most influence on the level of community participation in Idiot Village, Karangpatihan Village. Indicators that form social capital include trust, social networks, and norms. The most influential dimension of social capital is social networks with an average variance extracted value of 0.769. Meanwhile, the goodness of fit model value for the social network sub-variable shows the contribution to the level of community participation. Within PLS-SEM, we evaluated a reflective measurement (confirmatory) model and a structural model; descriptive results and path estimates are reported in the

Section 4.

3.1. Research Design

A qualitative case study forms the foundation of this research, enabling an in-depth exploration of social inclusion and empowerment within the specific sociocultural context of Karangpatihan village. Qualitative case studies provide rich, context-sensitive insights—particularly suitable for research with marginalised groups (

Usakli & Kucukergin, 2018). This method facilitates an in-depth understanding of the community’s values, interactions, and challenges, aligning well with the study’s goals of investigating inclusive tourism mechanisms through

Batik Ciprat.

To complement and extend the qualitative phase, we conducted a Phase 2 SEM-PLS was employed. This statistical technique allows for the modeling of complex relationships between constructs even with a small sample size and does not assume normal data distribution. SEM-PLS is widely accepted in tourism and hospitality research for its flexibility and robustness, particularly when exploring latent constructs such as social identity, empowerment, and quality of life (

Agyeiwaah et al., 2023). In this study, SEM-PLS was used to validate the relationships between dimensions of social capital, individual capacity, community involvement, and perceived quality of life among

Batik Ciprat participants. Our design is sequential exploratory: Phase 1 themes informed item development; Phase 2 tested relations among social capital, family support, individual capacity, community involvement, and quality of life.

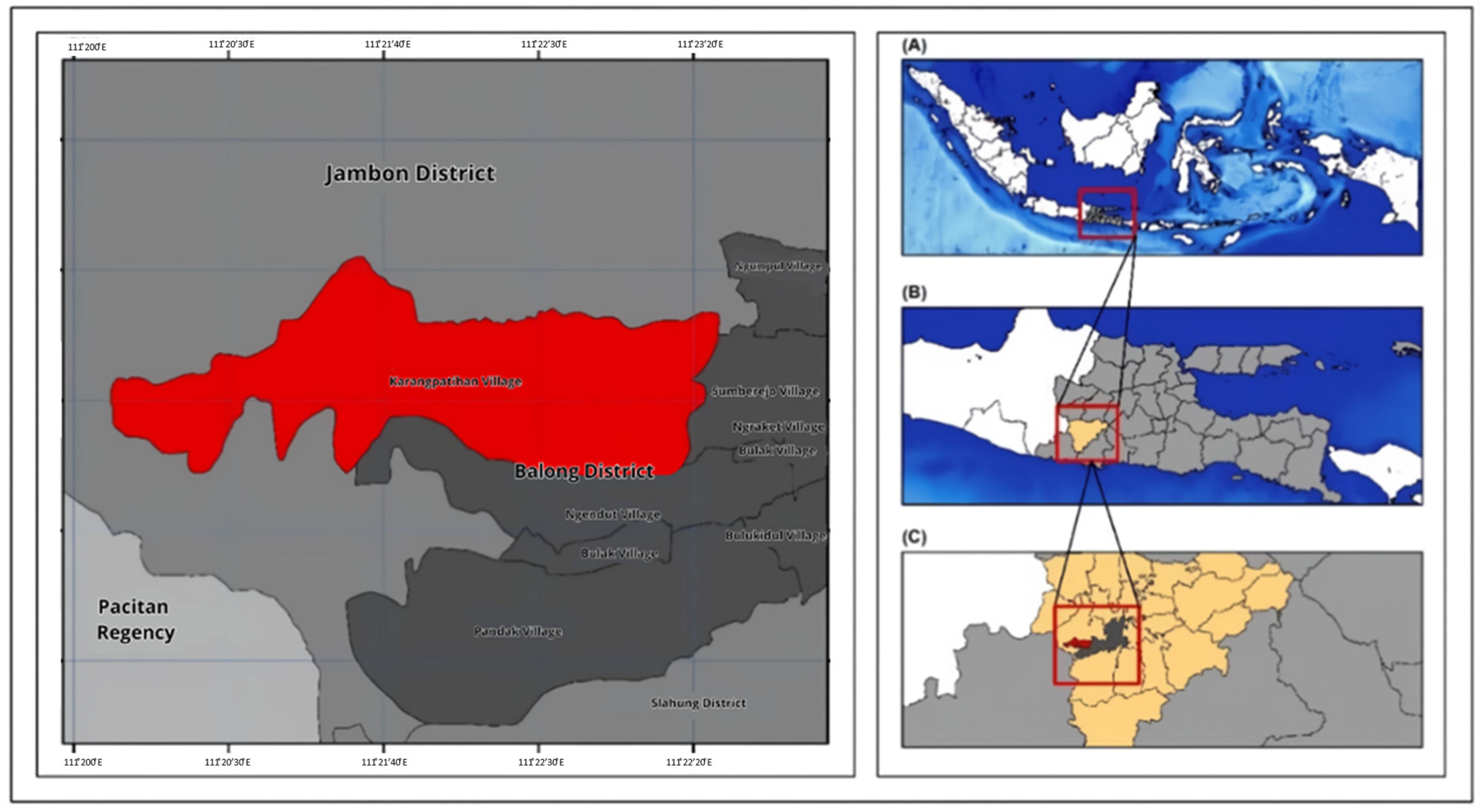

3.2. Study Area

The study took place in Karangpatihan Village, Ponorogo Regency, East Java, Indonesia a rural community recognised for empowering individuals with intellectual disabilities through the

Batik Ciprat initiative (

Figure 1). Often called the “Village of Hope,” Karangpatihan advances community-led inclusion, with

Batik Ciprat engaging participants in expressive batik production that now anchors the village’s tourism identity.

Participants included individuals with intellectual disabilities, family members/caregivers, community leaders, artisans, and organisation representatives in tourism and social services. This composition provided multiple perspectives on empowerment processes and tourism development at the village level.

3.3. Data Collection Techniques

We employed three qualitative techniques: participatory observation, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs). These methods align with best practices in qualitative tourism and disability research, which stress the importance of participant engagement, ethical sensitivity, and reflexivity (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021;

Rather et al., 2023).

Participatory observation: Researchers attended Batik Ciprat sessions, tourism exhibitions, and public events, documenting real-time interactions, informal communication patterns, and practical inclusion dynamics. This immersive approach allowed the team to observe real-time interactions, informal communication patterns, and the practical dynamics of social inclusion. It also enabled the identification of unspoken cultural norms and values influencing the participation of individuals with disabilities.

In-depth interviews: We conducted semi-structured interviews (n = 15) with artisans, caregivers/family, leaders, and programme staff. The guide elicited narratives on empowerment, trust, networks, identity, and tourism participation, allowing deeper exploration of emergent themes. This method allowed participants to share personal narratives, elaborate on the challenges they face, and describe how Batik Ciprat and tourism involvement have influenced their lives. The flexibility of semi-structured interviews facilitated deeper exploration of emergent themes, particularly regarding perceptions of empowerment, trust, and identity.

Focus Group Discussions (FGD): We held two FGDs were held with groups of Batik Ciprat participants and community stakeholders. These discussions encouraged interaction and collective reflection on shared experiences, revealing insights into community-level dynamics and the normalization of inclusive practices.

The research process adhered to rigorous ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, with simplified explanations and the use of visual aids provided to ensure clarity and accessibility, particularly for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the data collection process, and all interactions were conducted with respect and cultural sensitivity. Data for this study were collected through a structured questionnaire administered to a predetermined sample of respondents. The primary independent variable in this research is social capital, operationalised through three key dimensions: trust, social networks, and social norms. These dimensions were measured using the following indicators: MS1 (Trust) “Most people in this village can be trusted,” MS2 (Social Network) “I regularly exchange ideas with other villagers,” and MS3 (Social Norms) “People here share the same values about helping each other.” The dependent variable is Quality of Life (QoL), which includes multiple sub-dimensions such as material well-being, community engagement, emotional welfare, health, and security. All indicators were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire also included several items designed to measure levels of social trust, recognised as a central element of social capital (

Prayitno et al., 2025).

Ethics: We followed rigorous ethical procedures: informed consent (with simplified explanations/visual aids), and protection of anonymity and confidentiality throughout fieldwork; all interactions were conducted with respect and cultural sensitivity.

3.4. Sampling Strategies

The study used purposive sampling to identify participants who were directly engaged in Batik Ciprat or held roles influencing tourism development. Snowball sampling was additionally used to reach more marginalized individuals within informal networks. This strategy was particularly important in amplifying voices that are often excluded in mainstream tourism discourse, ensuring a representative portrayal of inclusion efforts.

3.5. Reflexivity and Researcher Positionality

Reflexivity was embedded throughout the research process. Researchers critically reflected on their own backgrounds, biases, and interactions with participants to minimize interpretive distortion. This was especially important given the intersecting layers of vulnerability experienced by participants, including disability, rural marginalization, and limited formal education. Reflexivity helped ensure that findings remained grounded in participant realities rather than researcher assumptions (

Rather et al., 2023).

3.6. Data Analysis

We analysed qualitative data using thematic analysis to identify recurrent patterns (e.g., trust dynamics, network formation, inclusion practices, well-being). We followed Braun & Clarke’s six-phase approach—familiarisation, coding, theme development, review, definition, and reporting ensuring a transparent audit trail (

Braun & Clarke, 2006).

To strengthen validity, data triangulation was employed. Findings from different methods were cross-referenced to ensure consistency and depth of insight. This methodological triangulation enhances reliability and credibility, especially in qualitative tourism studies where context and perception are central (

Usakli & Kucukergin, 2018).

Survey Instrument & Measures (NEW). Phase-1 themes informed a short survey measuring: Social Capital (trust, networks, inclusive norms), Family Support, Individual Capacity, Community Involvement, and Quality of Life on five-point Likert scales. Items were drafted from qualitative codes, expert-reviewed, and pilot-tested for clarity. Example items include: MS1 (“Most people in this village can be trusted”), MS2 (“I regularly exchange ideas with other villagers”), and MS3 (“People here share values about helping each other”).

3.7. Quantitative Analysis: SEM-PLS

The SEM-PLS component of the study analyzed relationships among constructs including social capital, family support, individual capacity, community involvement, and quality of life. This analytical tool was chosen for its capacity to model complex and exploratory pathways without the need for large samples or strict normality assumptions conditions often challenging in community-based rural research.

Indicator reliability was assessed through outer loading values, with values ≥0.70 considered valid. Construct validity and internal consistency were evaluated using Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), all of which met the standard thresholds. Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell Larcker criterion. Regarding RQ2, we interpret “interact” conceptually via linked structural paths among family support, individual capacity, community involvement, and quality of life; no moderation terms were estimated, and any mediation is discussed substantively rather than through formal tests.

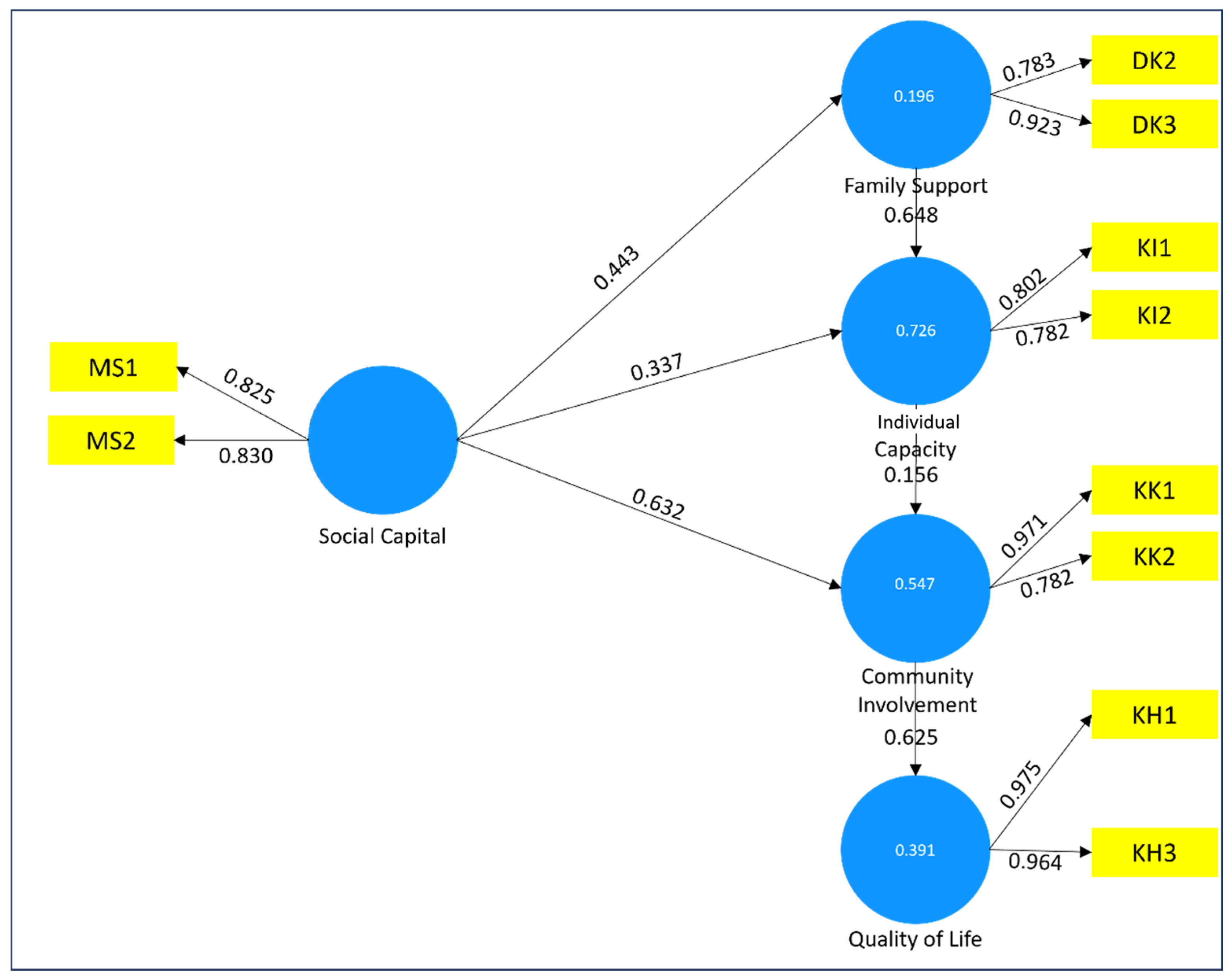

The structural model revealed significant pathways:

Social capital positively influenced family support, individual capacity, and community involvement.

Community involvement significantly improved perceived quality of life.

Individual capacity had limited influence on community engagement, suggesting the importance of social structures over individual attributes in inclusive tourism contexts.

Overall, PLS-SEM enables the quantification of abstract constructs (e.g., empowerment, inclusion), providing practical and theoretical insights for inclusive tourism design (

Agyeiwaah et al., 2023;

Auliah et al., 2025).

3.8. Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Findings

We integrated strands using a joint display that maps qualitative themes → constructs/indicators → structural paths and outcomes. Qualitative data provide context specific narratives, while PLS-SEM tests relations, bridging lived experience and empirical modelling. This integration informs local interventions and policy frameworks (

Fetters et al., 2013;

Handiman et al., 2024;

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021).

Leveraging both lenses, this study contributes to inclusive, interdisciplinary mixed-methods research in tourism. The approach validates the role of creative tourism in promoting social inclusion and offers a replicable village-scale framework for similar contexts.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical findings from the integration of qualitative data and Structural Equation Modelling–Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) analysis. We organise results into five themes: social networks, trust dynamics, inclusive norms, socio economic impacts, and model significance/validity. The results are structured around five core themes aligned with the study’s conceptual framework: social networks, trust dynamics, inclusive norms, socio-economic impacts, and the significance and validity of the analytical model. Each theme contributes to understanding how inclusive creative tourism—through Batik Ciprat empowers individuals with intellectual disabilities and enhances community development in Karangpatihan Village.

4.1. Social Networks

The findings reveal that social networks played a central role in facilitating the inclusion of individuals with intellectual disabilities within the Batik Ciprat initiative and the broader tourism ecosystem of Karangpatihan Village. These networks included family members, local residents, leaders, artisans, tourism actors, and NGOs, enabling access to resources, information, and opportunities otherwise out of reach. One artisan noted, “Workshop and exhibitions opened connections with visitors and tourism actors; we regularly share information and promote our products together” (Interview). Such testimonies confirm that networks operate as access points to both symbolic recognition and material resources.

Participatory observation illustrated that community-based organizations served as essential hubs for social interaction and collaboration. For example, regular

Batik Ciprat workshops and village tourism exhibitions allowed participants to showcase their work while engaging with visitors, fostering mutual understanding. This resonates with who argues that community-based tourism fosters strong local ties that promote sustainable development and improve community well-being (

Bozdaglar, 2023). Similarly affirm that integrating local perspectives into heritage tourism enhances sustainability and effective resource management (

Guerra et al., 2022).

The social capital embedded in these networks not only empowered individuals with disabilities to develop their artistic and entrepreneurial skills but also helped to redefine their roles within the community. The shift from passive beneficiaries to active contributors was particularly transformative, as it elevated their social status and enabled them to engage in village-level tourism planning and decision-making. These interactions built self-confidence and normalised inclusion.

PLS-SEM results supported these insights: social networks were validated within social capital (outer loadings ≥ 0.70; see

Appendix A), indicating a strong role in empowerment processes.

4.2. Trust Dynamics

Trust enabled effective collaboration and stakeholder engagement. It was cultivated through regular interactions, transparent communication, and shared goals. Leaders were perceived as fair and inclusive, as expressed by one participant: “We felt respected and safe during community activities,” while another added, “The village leader is fair in assigning roles” (FGD/Interview). These sentiments illustrate that trust generates psychological safety, which in turn motivates active involvement in Batik Ciprat and related tourism events. Participants reported that they felt “respected,” “appreciated,” and “part of the community,” sentiments that were reinforced during interviews and focus group discussions.

Structural results reinforced the role of trust as part of social capital (outer loadings ≥ 0.70;

Appendix B). The model indicated a significant link between social capital and family support (path coefficient = 0.349; t = 4.510), suggesting that trustful environments increase familial engagement in

Batik Ciprat.

This finding aligns with who noted that trust among stakeholders enhances cooperation, transparency, and joint commitment in tourism ventures (

Kuntariningsih et al., 2023). Their study illustrated that trusted community leadership empowered local populations to participate in and take ownership of tourism development initiatives, resulting in deeper engagement and improved sustainability

4.3. Inclusive Norms

The development of inclusive norms was one of the most transformative outcomes. Initially, individuals with intellectual disabilities faced social exclusion. Over time, as Batik Ciprat gained recognition, community attitudes shifted. Observations confirmed that “everyone sits and decides together” (observation), and participants described, “We held exhibitions without differentiation between disabled and non-disabled” (FGD). These inclusive routines embedded equality into daily practice, reinforcing the SEM-PLS finding that community involvement significantly enhanced quality of life (path coefficient = 0.768, t = 14.405). This transformation was facilitated by participatory practices that encouraged interaction, collaboration, and mutual appreciation between individuals with and without disabilities.

Inclusive norms became embedded in daily routines inclusive production sessions, planning meetings, and exhibitions where participants were treated as equals. These shared spaces for creative expression and decision-making helped dismantle social barriers and promote respect.

The SEM-PLS model confirmed this trend through the significant influence of community engagement on quality of life (path coefficient = 0.768, t-statistic = 14.405). As inclusive norms became institutionalized within the community, participants experienced a greater sense of belonging and increased social participation.

These findings support the notion that inclusive cultural norms in tourism-based creative industries can be cultivated through grassroots movements and community engagement. Such environments encourage marginalized individuals to express their identities and contribute meaningfully to community life, fostering a cultural shift toward acceptance and equity.

4.4. Socio-Economic Impacts

Batik Ciprat generated socio-economic benefits for participants and the wider community. Participation created income opportunities, vocational skill development, and quality-of-life improvements. A caregiver explained, “Income from batik supports both disabled and non-disabled community members, and training increases our confidence when meeting visitors” (Interview/FGD). Such earnings reduced dependency and elevated self-esteem, aligning with SEM-PLS results that community involvement strongly associated with quality of life (β = 0.624, t = 8.572).

Interviewees described how earnings from Batik Ciprat allowed them to contribute to household expenses, invest in personal development, and support community events. These economic activities instilled a sense of purpose and agency among participants, leading to increased self-esteem and optimism about the future.

The SEM-PLS results reinforced this narrative. Community involvement was strongly associated with quality of life (path coefficient = 0.624, t-statistic = 8.572), while indicators like economic independence (KH3 = 0.964) demonstrated strong construct validity. Notably, while emotional support and social well-being indicators did not meet the threshold for validity, financial and participatory contributions proved decisive in enhancing participant empowerment.

Prior studies affirm that inclusive creative tourism supports sustainable livelihoods and community resilience by empowering marginalised populations through hospitality and entrepreneurship (

Hapsari & Pramono, 2023). Their work underscores that integrating art-based economic activities into tourism can yield measurable improvements in local well-being, community identity, and collective prosperity. Branding cues observed during fieldwork included routine

Batik Ciprat workshops and village exhibitions that presented the craft to visitors as Karangpatihan’s signature attraction. Across the study-area description and the results,

Batik Ciprat is consistently referenced as anchoring the village’s tourism identity, reinforcing recognition among tourists and local stakeholders.

4.5. Model Significance and Validity

The overall SEM-PLS model demonstrated strong validity and reliability, confirming the robustness of the framework (

Table 1). Indicators with low loadings (e.g., MS3 norms, DK1 emotional support, KI3 independence) were qualitatively supported. For instance, one respondent clarified: “

Skills improved, but I still need encouragement from the community to stay involved” (Interview). This illustrates why some indicators failed statistically but remained meaningful contextually, reinforcing the value of integrating qualitative insights with quantitative measures. The outer loading values for valid indicators ranged from 0.783 to 0.974, with high scores observed for constructs such as family participation, skill level, group interaction, and income generation.

Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, verifying adequate construct distinctiveness and supporting interpretation of the structural relations.

The structural model analysis yielded several noteworthy findings (

Figure 2):

Family support significantly influenced individual capacity (path coefficient = 0.779, t-statistic = 17.589).

Social capital had a direct and substantial impact on family support (0.349), individual capacity (0.157), and community involvement (0.768).

Although individual capacity (e.g., education and skills) contributed meaningfully to personal development, it did not significantly influence community engagement (path coefficient = 0.006, t-statistic = 0.130), suggesting that social inclusion is more strongly shaped by external support and communal structures than individual attributes alone. Consistent with our qualitatively led design, we interpret the interplay among family support, individual capacity, and community involvement through these linked paths; no explicit moderation terms were estimated.

These results support

Hair et al. (

2019) and

Abdul-Rahman et al. (

2023), who emphasize the necessity of well validated models in tourism and social entrepreneurship research. They argue that robust SEM-PLS analyses provide actionable insights that bridge theoretical constructs with practical interventions, especially in contexts of inclusion and empowerment.

5. Discussion

Findings from Karangpatihan Village show how inclusive creative tourism, grounded in social capital, transforms the lives of individuals with intellectual disabilities while strengthening rural cohesion. We illustrate how networks, trust, and inclusive norms operationalised via Batik Ciprat catalyse empowerment and a distinctive tourism identity. Below, we interpret these results within relevant theoretical frames, assess scalability, note interdisciplinary linkages, and discuss developmental potential, consistent with reviewer requests to clarify contribution and scope.

5.1. Social Capital and Collective Empowerment

Empirical evidence confirms social capital as a foundation for inclusive practices. In Karangpatihan, mutual support networks expanded access to tourism opportunities and strengthened self-worth and agency. Trust among residents, leaders, and stakeholders enabled equitable participation, while inclusive norms became institutionalised through daily interactions. This was echoed in field accounts, such as a participant noting: “We felt respected and safe during community activities” (FGD). The triangulation of qualitative voices and SEM-PLS results demonstrates how social capital serves as a bridge between empowerment and community transformation.

These findings reinforce that community involvement promotes collective action and adaptations resonant with local identity (

Auliah et al., 2025). The strength of communal ties and shared responsibilities fosters sustainable development outcomes. Importantly, social capital served as a bridge between individual empowerment and community-wide transformation, providing the social infrastructure necessary for marginalized individuals to meaningfully contribute to and benefit from tourism initiatives.

The model reflects community-based tourism (CBT) principles local control, participatory governance, and socio-cultural authenticity while extending CBT by embedding disability inclusion within creative tourism. Via art-based enterprise like Batik Ciprat, tourism is reframed from commodified product to co-created platform for empowerment and social justice, aligning with inclusive/accessible tourism discourse.

5.2. Challenges of Scalability and Cultural Adaptability

While locally effective, scaling inclusive tourism models is challenging. Social capital is deeply context-dependent, shaped by culture and local leadership. Replication without adaptation risks diluting empowerment values. Evidence from Asia supports this concern: in Thailand, weaving cooperatives involving disabled women succeeded because of cultural tailoring, while in the Philippines, community-based ecotourism integrated persons with disabilities as guides and artisans, but only thrived when aligned with local norms. These cases highlight that replication must balance scalability with cultural specificity.

The literature indicates that scaling with cultural specificity needs frameworks prioritising local ownership and empowerment within sustainable tourism, balancing economic aims with cultural environmental integrity (

Scheyvens & van der Watt, 2021). Thus, scaling should favour adaptation, retaining inclusive values while tailoring practices to each community’s sociocultural fabric.

Adaptive strategies include leadership capacity-building, stakeholder co-design, and alignment with local development goals. These keep initiatives grounded in community values and responsive to local constraints. Such alignment fosters ownership, sustaining engagement and enhancing long-term impact (

Auliah et al., 2025).

Tourism development should be embedded in broader social policy supporting disability rights and rural innovation. Absent institutional backing infrastructure, inclusive education, and market access community initiatives risk falling short of their potential.

5.3. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Sustainability

Sustaining inclusive creative tourism requires interdisciplinary approaches bridging sociology, economics, cultural studies, and disability advocacy. Batik Ciprat illustrates that art-based initiatives can reduce stigma and create identity-based inclusion. Comparative evidence shows parallels: Thai weaving initiatives reframed disability as cultural capital, while Filipino ecotourism built cross-sector alliances to sustain impact. These examples reinforce that inclusion must be framed not only as economic opportunity but also as social justice and cultural recognition.

The literature identifies creative tourism models that prioritise local identity and collaboration (

Duxbury et al., 2020). Such models suit empowerment challenges faced by persons with disabilities by enabling customised activities aligned with abilities, aesthetics, and traditions.

Batik Ciprat exemplifies a low-barrier, culturally grounded art form supporting expression and income without extensive formal training.

Sociologically, inclusive creative tourism helps reconstruct social identities and challenge normative views of ability and productivity. Economically, initiatives build local value chains, retain profits in the community, reduce dependence on external actors, and create employment for those typically excluded.

Environmentally, integrating creative tourism into sustainable development reduces the extractive pressure on natural resources by shifting the tourism focus from passive consumption to interactive cultural participation. These multidimensional benefits underscore the necessity of integrated policy-making and program design that span multiple domains.

5.4. Reinforcing Inclusive Development Through Arts and Tourism

Integrating arts into tourism both diversifies offerings and amplifies marginalised voices, catalysing social change. In Karangpatihan, Batik Ciprat operates as both an artistic and social tool, enabling individuals with intellectual disabilities to reclaim public space and reshape narratives. This aligns with broader trends: creative tourism in Bali’s inclusive dance workshops and Thailand’s community weaving programs similarly demonstrated how participatory arts shift perceptions and generate income. Such cases illustrate that art–tourism synergies not only challenge stigma but also create a more empathetic tourist–local encounter.

Argue that creative tourism models thrive when local participation and cultural expression are central to their operation (

Baixinho et al., 2021). The Karangpatihan case exemplifies this principle, as the community’s commitment to artistic inclusivity enhanced both the sustainability and the authenticity of its tourism offerings.

Celebrating diverse abilities through art challenges stigma and reframes disability as cultural capital. The participatory nature of creative tourism fosters tourist local interaction, breaking stereotypes and promoting empathy. Thus, inclusive creative tourism does not merely accommodate disability it leverages it as a strength, enriching visitor experience and social fabric.

This form of inclusive development also aligns with global movements toward accessible tourism, which emphasize universal design, rights-based approaches, and inclusive storytelling. As governments and organizations increasingly adopt these principles, examples like Karangpatihan offer valuable blueprints for effective implementation at the grassroots level.

5.5. Implications for Policy and Practive

The findings have strong implications for policy and practice. Beyond Karangpatihan, inclusive creative tourism should be formally recognised as a rural development pathway. Lessons from Thailand and the Philippines show that sustainable outcomes require policy frameworks supporting accessible infrastructure, inclusive education, and market access, combined with community ownership. This underscores the need for governments and NGOs to integrate inclusive creative tourism into mainstream rural development planning. First, inclusive creative tourism should be formally recognized as a viable pathway for both disability empowerment and rural development. Investment in such initiatives requires integrated policies that support inclusive education, infrastructure accessibility, and small business development.

Second, capacity building should be prioritized not only for individuals with disabilities but also for the wider community and tourism operators. Training programs that enhance awareness, inclusivity, and co-creation are essential to scaling inclusive tourism without diluting its values.

Third, partnerships between local communities, academic institutions, and the tourism industry can provide the technical support and networks needed to enhance the visibility and sustainability of inclusive tourism ventures. These collaborations should be guided by principles of equity, reciprocity, and cultural sensitivity.

Lastly, monitoring and evaluation frameworks must be adapted to capture the nuanced impacts of inclusive tourism. Traditional economic indicators, while important, fail to reflect the social transformations and shifts in community dynamics that define success in empowerment-oriented initiatives.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the transformative potential of inclusive creative tourism in empowering individuals with intellectual disabilities and advancing sustainable rural development. Using Karangpatihan’s Batik Ciprat as a case, we demonstrate how trust, networks, and inclusive norms underpin participation, skill development, and economic independence. By employing a qualitatively led mixed-methods design with PLS-SEM, we confirm that community engagement and participatory practices significantly improve quality of life and reinforce collective identity.

Findings highlight that inclusive tourism must be community-driven, culturally embedded, and institutionally supported. Social capital enables collaboration while nurturing spaces where diversity is celebrated and marginalised voices amplified, echoing inclusive/accessible tourism principles (

Biddulph & Scheyvens, 2018;

Buhalis & Darcy, 2010;

Scheyvens & van der Watt, 2021).

Batik Ciprat illustrates how creativity and local culture both challenge stigma and promote inclusive narratives within rural tourism.

Sustaining and scaling require balancing scalability with cultural specificity. Lessons from Thailand and the Philippines confirm that replication succeeds only when community ownership and cultural adaptation are prioritised. Thus, interdisciplinary collaboration and tailored policy support are critical for ensuring long-term viability of inclusive creative tourism initiatives (

Duxbury et al., 2020;

Scheyvens & van der Watt, 2021).

Empirical findings show that social capital positively influences family support and community involvement and community involvement significantly enhances quality of life, while individual capacity does not directly drive community engagement, underscoring the primacy of social structures over individual attributes. Although some indicators loaded weakly in SEM-PLS (e.g., norms, emotional support), qualitative evidence confirmed their salience in practice. Moreover, Batik Ciprat contributes to village-scale branding and visitor engagement, strengthening the inclusion–creativity nexus.

Practical Implications. Inclusive creative tourism should be institutionalised through co-design with disability advocates and adequate budgeting for accessible information (e.g., wayfinding, websites) and co-created workshops (

World Tourism Organization, 2013). Operators should implement staff training on inclusive service and safeguarding and standardize accommodations across the visitor journey. NGOs and policymakers must support market access through inclusive digital storytelling and equitable partnerships. Monitoring frameworks should track inclusion metrics (e.g., participation rates, income contribution, perceived dignity/safety) alongside conventional economic indicators, ensuring a holistic evaluation of success.

Further Research. Future studies should test the model across multiple villages/regions and adopt longitudinal designs to capture trajectories of inclusion and quality of life. Comparative research could examine alternative art-based enterprises (e.g., weaving in Thailand, woodcraft in the Philippines) to assess transferability. Researchers should also extend accessible information audits across the destination value chain. Where feasible, mixed-methods integration with transparent joint displays and refined measurement (e.g., item-pruning decisions) should be applied, following best-practice guidelines (

Hair et al., 2019).